Abstract

Objectives

To help address the unique needs of parents of children with chronic pain, a four module, parent-only, group art therapy curriculum was designed and implemented within an interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation treatment program. We evaluated perceived satisfaction and helpfulness of the group intervention.

Methods

Fifty-three parents of children experiencing chronic pain enrolled in a day hospital interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation program participated. The voluntary parent art therapy group was offered one time per week for one hour. Participants completed a measure of satisfaction, helpfulness, and perceived social support at the end of each group session.

Results

Parents enjoyed participating in the group, agreed that they would try art therapy again, and found it to be a helpful, supportive, and validating experience.

Conclusions

Initial results are promising that group art therapy is an appropriate and helpful means of supporting parents of children with chronic pain during interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation.

Keywords: chronic pain, art therapy, child and adolescent, parents, pain rehabilitation, treatment intervention

Parents play a crucial role in the rehabilitation process of a child with chronic pain as they represent a major aspect of the child's immediate social context (Vowles, Cohen, McCracken, & Eccleston, 2010). Parenting a child with chronic pain is stressful and associated with increased emotional, physical and psychological distress, as well as financial hardships and interpersonal difficulties (Hunfeld et al., 2001; Jordan et al., 2007; Palermo & Eccleston, 2009). Such difficulties for parents of children with chronic pain influence the child's pain experience. Notably, increased levels of parent emotional distress have been linked to higher levels of disability and child-reported pain (Sieberg et al., 2011; Caes et al., 2011). Additionally, children learn how to respond to their pain by observing their parent's own pain-related distress and protective behaviors directed towards them. For example, when a parent allows a child to avoid regular activities or attends to their child's pain symptoms frequently, the child learns that ceasing to function in the face of pain is an appropriate coping response (e.g., Simons, Claar & Logan, 2008).

The relationship between parent functioning and a child's pain experience is reciprocal. Greater pain related-disability in children has been associated with increased levels of parent psychological distress and deficits in healthy family functioning (Palermo, Putnam, Armstrong, & Daily, 2007; Logan & Scharff, 2005) and research indicates that chronically witnessing a child in pain can have significant emotional and psychological effects on a parent (Eccleston, Crombez, Scotford, Clinch, & Connell, 2004; Jordan et al., 2007). Such evidence supports that there is a need to clinically address these challenges with interventions designed for parents only. Targeting the well-being of parents of children with chronic pain would not only provide direct benefits to parents themselves, but also has the potential to support optimization of their ability to support the child's recovery facilitating downstream behavioral changes in both parent and child's pain-related functioning. Despite assertions that we must better address parent pain-related distress separate from a child's treatment (Jordan et al., 2007; Palermo and Eccleston, 2009; Vowles et al., 2010) and the recent release of a Cochrane Review surmising that there is good efficacy for the inclusion of parents in psychological therapies aimed at pain reduction and management for children with painful conditions (Eccleston, Palermo, Fisher, & Law, 2012), there continues to be a dearth of parent-only interventions available for this population.

To address this need, we implemented a pilot parent-only art therapy group curriculum for parents of children enrolled in an intensive day hospital pediatric pain rehabilitation program. The group art therapy intervention was designed specifically to target the struggles of parents of children with chronic pain (seeking support, managing feelings of burden, helplessness, isolation, fear, and lack of time for self [Jordan et al., 2007]). This parent-only art group is the first of its kind and represents an innovative approach to addressing the needs of parents in this treatment setting.

The curriculum was intentionally designed for use with groups, rather than individuals. Group art therapy within a medical setting can be particularly beneficial because the group atmosphere inherently helps to increase universality of a medical condition, decrease feelings of isolation that medical treatments often trigger, and offer space for people with similar needs to provide mutual support for each other through collaborative problem solving, learning from the feedback of other members, and examining issues from different perspectives (Malchiodi, 2012b; Liebmann, 2003; Councill, 1999). Additionally, the modules developed for this intervention are intended to facilitate a parent's reflection of their own experiences, feelings, sacrifices, and difficulties since the onset of their child's pain, as opposed to asking the parents to retell their child's pain history and symptomology. In this way, parents are encouraged to use their unique voice and narrate their own story. Wiksell and Greco (2008) advise that when working with the parents of child with chronic pain it is necessary to work collaboratively with the family and give them an opportunity to be heard. In order for the parents to be heard, however, they must have a voice through which to speak and express their experience; thus, we offer art as a voice.

Why art therapy?

Art therapy is a master's level mental health profession based on a belief in the power of the creative arts process to enhance and improve emotional, physical, and mental well-being of individuals of all ages (Malchiodi, 2007). Art therapy is commonly used to facilitate symbolic and non-verbal communication. This can be helpful when a feeling or event is too overwhelming, difficult, confusing, or painful to speak about. Art therapy can be used independently or in collaboration with other disciplines for treatment, assessment, and research. (Malchiodi, 2007). Although evidenced-based practice is a relatively new phenomenon for the discipline of art therapy (Gilroy, 2006), the clinical benefits of art therapy are unique and numerable, as witnessed in practice by pioneers of the field, art therapists, treatment teams, and clients alike. Potential benefits of art therapy include relaxation and reduction of stress and stress-related symptoms, reduction in anxiety and negative mood, assistance with communicating and expressing difficult feelings and experiences, an increase in self-esteem and self-awareness, resolution of conflicts, grief, and problems, improvement in quality of life, development of interpersonal skills, personal empowerment, and an increase of creativity, imagination, and visual thinking skills (e.g. Kaplan, 2000; Malchiodi, 2007, 2003; Caddy et al., 2011).

Presently, no literature exists on the application of art therapy with parents of children with chronic pain, but related research suggests potential benefits of using art therapy with this population. For example, in a case study with the family of a 6-year-old child living with chronic pain, Palmer and Shephard (2008) reflected that using an art-based approach was effective because the process offered the family a way to externalize their experiences and create concrete images to talk about. In this way, art offered emotional distance and validation of the experience by making it tangible for others to see (Malchiodi, 2012b). Another study, evaluating the efficacy of a creative arts intervention with family caregivers of patients with cancer, found that family caregivers reported significant reductions in stress and anxiety levels as well as an increase in positive emotions after participation in the creative arts intervention (Walsh, Culpepper Martin, & Schmidt, 2004). Finally, in a small, randomized controlled trial, conducted with healthy adults in a group setting, individuals were asked to write a 10-item `to do' list of their most immediate worries and concerns. Those who actively participated in group art therapy experienced significantly greater reductions in anxiety and negative mood symptoms as compared to the control group, who only viewed art (Bell & Robbins, 2007).

The overarching clinical goals for the group were to (1) implement a supportive, therapeutic intervention designed specifically for parents of children with chronic pain, (2) encourage parents to identify and express feelings associated with their experience of their child's journey with pain, (3) facilitate self-expression through the arts, (4) increase parent's feelings of validation for the difficulties present within their experience as a caretaker of a child managing chronic pain, and (5) increase perceived social support.

In this pilot project we evaluated parent's initial responses to the art therapy groups, measured by perceived satisfaction and helpfulness, in order to determine if this intervention could be a valuable, long-term addition to the interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation program and what changes are warranted to optimize the intervention. Given initial support for the therapeutic benefits of art therapy for adults, we hypothesized that parents would be satisfied with the group art therapy intervention and find it helpful (e.g., enjoy art as a means of self-expression).

Methods

Art therapy modules

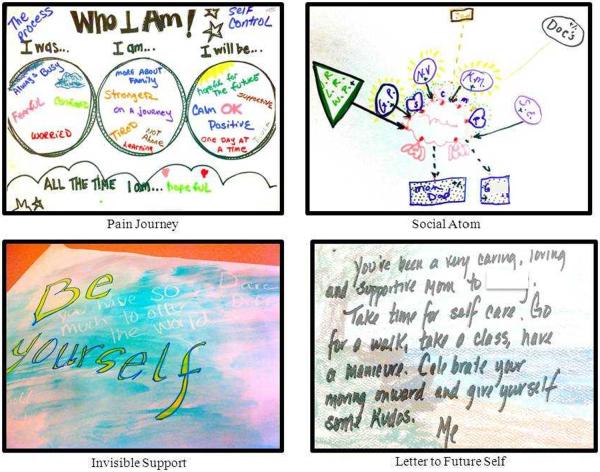

The treatment intervention is comprised of four independent modules. A four module curriculum was established because the average length of stay for patients in the rehabilitation program is 3–4 weeks and we wanted to limit redundancy in the group experience. Modules were developed by an art therapist and two pediatric psychologists who specialize in chronic pain management. The modules include: Pain Journey, Social Atom, Invisible Support, and Letter to Future Self. Table 2 includes details of the goals and content of each module and Figure 1 presents examples of artwork created during each module.

Table 2.

Description of Program Modules

| Module | Description | Goals | Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Module 1: Pain Journey | Participants are asked to create a visual timeline of their journey since the onset of their child's pain which includes elements of past, present, and future. Emphasis is placed on reflecting, expressing, and validating the parent's experience and the effect that their child's pain has had on their life (e.g. relationships, career, burdens, and loss). Participants are also challenged to look towards the future and envision wellness for themselves and their child despite current struggles. | 1. To identify personal struggles, fears, and barriers present when caring for a child with chronic pain. 2. To acknowledge and validate the difficulty of the healing journey for parent as well as child. 3. To encourage parents to look towards the future with hope and positivity. |

|

Key themes:

| |||

|

| |||

| Module 2: Social Atom | Adapted from Joseph Moreno's social atom inventory (Buchanan, 1984) ,this module asks participants to utilize symbols and shapes to create a “map” of social supports and important people in their life. Next they are encouraged to reflect and notate if each relationship is stimulating, energizing, and supportive (positive) or draining and conflict-ridden (negative). Participants are also asked to identify different people in their life who serve a specific purpose (e.g. a person you would call if you had a difficult day) and commit to contacting one person from their social atom in the coming week. | 1. To explore, identify, and reflect on interpersonal relationships. 2. To identify positive and negative relationships/ support systems. 3. To reflect on the importance of maintaining personal relationships. 4. To reconnect with friends, family |

|

Key themes:

| |||

|

| |||

| Module 3: Invisible Support | From a group of 18 descriptive phrases and values written on button pins (e.g., “be confident,” “be admirable”) participants are asked to choose a value that is important to them as a parent or a value that they are working on strengthening. 10 minutes are given for free writing about the personal meaning and importance of this value. Next, they are guided to write this word on a large piece of paper in permanent marker and embellish it as they feel inspired. The individual papers are then passed around the circle whereupon each participant writes a supportive/ inspirational word, quote, phrase, or draws a symbol on their peer's paper in white crayon. The messages written in white crayon on white paper are invisible until the participant paints over his paper with watercolors to make the messages appear. Activity concludes with discussion about the metaphor of how those who support us may sometimes feel invisible. | 1. To identify important values. 2. To cultivate support for peers and share positive self-statements with others. 3. To receive support from peers. 4. To create something that is tangible and reflective of the support which they receive in group. 6. To increase relaxation through the use of watercolors. 7. To increase imagination and artistic self-expression. |

|

Key themes:

| |||

|

| |||

| Module 4: Letter to Future Self | Participants are asked to envision themselves in the future, after their child has graduated from the program. Participants are encouraged to identify potential difficulties that could arise during this transitory time period. Participants are then asked to write a letter to their future self and to the other parents- as a way to affirm, validate, and support themself in the future. These letters are mailed out 2 weeks after their child's graduation to support participants post-discharge. | 1. To increase parent's ability to self- validate 2. To cultivate support, empathy, and encouragement for one self and other. 3. To identify potential barriers for when their child is back home and preemptively use positive self- statements to manage distress. |

|

Key themes:

| |||

Figure 1.

Sample images from each module. All artwork was created by participants in the parent art therapy groups

Procedures

The group was offered one time per week for one hour. The first five to ten minutes involved introductions and orientation to the goals of group art therapy. The subsequent 30 minutes were spent dispersing art materials and doing the art activity. Participants were offered a myriad of art supplies (e.g. collage, markers, oil pastels, water colors) and encouraged to explore new and unfamiliar materials. During art making, quiet, relaxing music was played in the background. After art making, five to ten minutes was reserved for discussion, reflection, and sharing of creations. The last 10 minutes of group was designated for closure, administration of the Satisfaction/Helpfulness Survey, and clean up. Participation in the group was voluntary. Participants were not required to attend all four modules of the program. Completion of any surveys was optional and participation in the group was not contingent on or hindered by completion of measures.

Setting

The pain rehabilitation program is an interdisciplinary day hospital program for children and adolescents, ages 8–18, with persistent and chronic extremity pain, typically with neuropathic features that cause significant functional impairment. The program is located in the northeast United States as part of a large, urban pediatric hospital. Patients are treated with a combination of interventions from several disciplines, including physical therapy, occupational therapy, psychology, nursing, and medicine (see Logan et. al., 2012 for full description of the program). Art therapy was first introduced to the program for patients in June of 2011.

Parents and families are an integral part of the child's rehabilitative treatment and are asked to be active participants in the program by attending hour-long daily family sessions with one of the disciplines (e.g., parent-observed physical therapy, family therapy with the treating psychologist). As part of the program, parents are also provided a weekly, two hour long multidisciplinary psychoeducation and support group. Prior to implementation of the art therapy group, the two- hour weekly parent psychoeducation and support group was the only parent-only intervention offered in the program.

Participants

Participants were parents of children and adolescents enrolled in an intensive interdisciplinary pediatric pain rehabilitation day hospital program from October 2011-June 2012. The parent art therapy group was offered to parents as part of clinical care. Parents were given a brochure with information about the group at their child's admission. Of the 51 families whom completed the pain rehabilitation program during that time, 82% (n=42) chose to participate in the parent art therapy group. Reasons for choosing to not participate included scheduling conflicts or disinterest in the group. Among the 42 participating families, 29 families only had mothers in attendance (83% were married), two were father only (100% were married), and 11 had both mother and father present (91% were married). Thus, there were a total of 53 individual participants (40 mothers, 13 fathers). Demographic information about each participant was collected with IRB approval to retrospectively examine clinical records for research purposes. Among participants, 88.7% were White (non-Hispanic) and approximately 60% of participant's children were experiencing neuropathic pain in one or both lower extremities (e.g. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome). Median pain duration was 10 months (see Table 1 for further details).

Table 1.

Participant & Group Characteristics (n=53)

| Variable | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Number of families | 42† |

| Relationship to patient (n=53) | |

| Mother | 75.5% |

| Father | 24.5% |

| Ethnicity | |

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 88.7% |

| Hispanic | 11.3% |

| Child's pain location | |

| Lower extremity (-ies) | 60.4% |

| Upper extremity | 5.7% |

| Mixed upper/lower and/or back | 30.1% |

| Torso | 3.8% |

| Is the child's pain neuropathic? | |

| Yes | 62.3% |

| No | 37.7% |

| Child's pain duration (months) | median= 10 |

| range= 2–144 | |

| Number of modules completed (n=53) | |

| 1 | 49.1% |

| 2 | 28.3% |

| 3 | 17.0% |

| 4 | 5.7% |

| Participant lateness | |

| Pain Journey (n=26) | 7.7% |

| Social Atom (n=27) | 7.4% |

| Invisible Support (n=19) | 10.5% |

| Letter to Future Self (n=23) | 26.1% |

Note. Some parents alternated weeks attending the program; therefore, there are less family units than there are parents.

Measures

Satisfaction and helpfulness survey

The Satisfaction and Helpfulness Survey is expanded and adapted from Beardlsee et al.'s (1990) treatment helpfulness and feasibility measure, which has been used in several treatment outcome studies for children with chronic physical conditions (Beardslee, 1990; Szigethy et al., 2007). This adapted version is a 15 item self-report questionnaire consisting of two subscales: helpfulness (five items) and satisfaction (five items) as well as one item on perceived support, one item on feasibility, and three open ended items. Based on these items, satisfaction is defined by report of overall enjoyment in the group experience, willingness to participate in the group again, and recommendation of the group to other parents of children with chronic pain, while helpfulness is defined as gaining new insights about parenting a child with chronic pain, feeling validated by working with other parents, and helpfulness of the art modality in self-expression. Open-ended questions on this measure ask: (1) What would you change about today's group? Please describe what and why. (2) What was the most helpful aspect(s) of today's group activity? & (3) Through this group, has your understanding of art therapy changed? Why or why not? Responses from the open-ended questions were coded and summed to obtain frequencies of responses (see Data Analysis and Results for further details).

Closed-ended questions were measured on a five point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating stronger agreement. Items 2, 4, and 11 are reverse coded, meaning that lower ratings are more favorable. Prior to its implementation, psychologists with expertise in pediatric pain treatment and survey development reviewed the measure for clarity, accuracy, and readability. Internal consistencies of the helpfulness subscale ranged from .70–.85 across the four modules, and from .73–.82 for the satisfaction subscale, indicating acceptable internal reliability.

Participant engagement

Participant engagement was measured using the Pittsburgh Rehabilitation Participation Scale (PRPS) (Lenze et al., 2004). This measure utilizes a six point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (“none” e.g. refusal to participate) to 6 (“excellent” e.g. full participation, completion of exercise, and expression of interest in future sessions) to assess a participant's effort and motivation in a therapy session, as perceived by the clinician. Higher scores indicate greater engagement in treatment. The PRPS has demonstrated good validity and high inter-rater reliability (Lenze et al., 2004).

Group characteristics

Group characteristics were recorded for each participant in order to describe the groups and explore potential factors that could influence the group experience. These include the number of participants in each group, what phase of treatment participants were in at the time of the group, if participants arrived on time, if the participant finished the activity, and the total number of art therapy modules that the participant completed.

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted in SPSS version 19. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, means, standard deviations, and ranges, were computed for all variables of interest. Internal consistency estimates for this sample were calculated for the Helpfulness/Satisfaction Survey and reported above. Responses to open-ended questions were examined collectively across all modules. The first author (MP) worked with the senior author (LS) to group responses into categories delineated for each question. A blind coder (MR) was then brought in and asked to categorize responses based on the categories developed by the first and senior author. The blind coder was also invited to propose new categories if she felt that the given categories were not an adequate fit for responses. The first author, senior author, and blind coder then met and came to a consensus regarding the categories for each question as well as appropriate coding of responses; categories were not conceptually altered, but specific wording of some categories was modified to clarify meaning. Finally, a second independent blind coder (GB) was asked to code the data based on the consensus categories. The second blind coder was also given definitions for each category, written and agreed upon by the first author, senior author, and first blind coder. Agreement between consensus codes and the second blind coder's categorizations was calculated using kappa coefficients. These are reported in the results.

Results

Group characteristics

On average, there were 4 participants in each group session (range 2–6). Approximately 50% of participants completed more than one module. Nearly half of parents who completed the Letter to Future Self module were in their discharge week of the program. Over half of parents who completed the Invisible Support module were mid-treatment. Participants were generally on time (73.9–92.3%), although more participants were late to the Letter to Future Self module than other modules (n=26.1%). It is notable that nearly half of participants were not able to complete the Letter to Future Self exercise within the allotted group time. Participant engagement ratings were highest in the Social Atom (mean= 5.22) and Invisible Support modules (mean= 5) with means in the very good- excellent range. Participant engagement ratings were lower in the Pain Journey (mean=4.65) and Letter to Future Self (mean=4.70) with mean ratings in the good-very good range. For additional group descriptive characteristics, please refer to Table 1.

Satisfaction, Helpfulness, and Support

The Pain Journey was perceived as the most helpful module, while Invisible Support was perceived as the most satisfying to participate in (see Table 3). Generally, total scores on the satisfaction subscale were higher than on the helpfulness subscale. For all modules, except the Letter to Future Self module, “I enjoyed participating in this group” was the most highly endorsed item. For the Letter to Future Self, it was the second most highly endorsed. Results across modules revealed that parents felt supported through the group experience; however, participants reported that they were unsure if the group helped them to understand something new about their experience parenting a child with chronic pain or if they felt more comfortable expressing feelings through art than talking, as these items were among the lowest endorsed for all modules.

Table 3.

Item Means, Standard Deviations, and Ranges for Modules

| Pain Journey (n=26) | Social Atom (n=27) | Invisible Support (n=19) | Letter to Future Self (n=23) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Subscale | Item | Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range |

| Satisfaction | 1. I enjoyed participating in this group. | 4.46 (.76) | 3–5 | 4.33 (.55) | 3–5 | 4.58 (.51) | 4–5 | 4.39 (.50) | 4–5 |

| 2. It was difficult to express my feelings through art. | 2.62 (1.06) | 1–4 | 2.48 (.94) | 1–4 | 2.16 (.83) | 1–4 | 2.09 (.79) | 1–4 | |

| 5. I would recommend this group to other parents of children with chronic pain. | 4.39 (.75) | 2–5 | 4.15 (.66) | 3–5 | 4.26 (.56) | 3–5 | 4.22 (.60) | 3–5 | |

| 6. I would try art therapy again. | 4.16 (.90) | 2–5 | 4.19 (.62) | 3–5 | 4.37 (.50) | 4–5 | 4.22 (.80) | 2–5 | |

| 11. I am skeptical about the advantages of attending an art therapy group. | 2.19 (.98) | 1–4 | 2.03 (.76) | 1–4 | 1.79 (.63) | 1–3 | 1.91 (.73) | 1–4 | |

| Total Subscale Score | 20.0 (3.57) | 11–25 | 20.1(2.49) | 15–25 | 21.3 (2.16) | 17–24 | 20.8(2.59) | 16–25 | |

| Helpfulness | 3. This group helped me to understand something new about my experience parenting a child with chronic pain. | 3.92 (.98) | 2–5 | 3.63 (1.04) | 1–5 | 3.47 (.61) | 2–4 | 3.50 (.84) | 2–5 |

| 8. The art/writing activity was a good way to express my feelings as a parent of a child with chronic pain. | 4.08 (.89) | 2–5 | 4.04 (.71) | 2–5 | 4.16 (.50) | 3–5 | 4.02 (.78) | 2–5 | |

| 9. It was validating to talk about and hear other parent's experiences. | 4.42 (.76) | 2–5 | 4.26 (.71) | 2–5 | 4.32 (.67) | 3–5 | 4.41 (.62) | 3–5 | |

| 10. I felt comfortable expressing feelings through art that I do not feel comfortable talking about. | 3.42 (1.14) | 1–5 | 3.40 (.93) | 1–5 | 3.32 (1.0) | 2–5 | 3.07 (1.07) | 1–5 | |

| 12. Overall, the group was helpful to me as a parent of a child with chronic pain. | 4.31 (.74) | 2–5 | 3.96 (.81) | 2–5 | 4.11 (.76) | 3–5 | 3.94 (.83) | 2–5 | |

| Total Subscale Score | 20.2(3.5) | 11–25 | 19.3(3.35) | 10–25 | 19.6(2.61) | 15–23 | 18.9(3.18) | 13–24 | |

| Feasibility Support | 4. It was difficult for me to attend this group due to time, schedule conflicts, or other reasons. | 1.69 (.88) | 1–4 | 1.08 (1.0) | 1–5 | 1.84 (1.12) | 1–4 | 1.57 (.73) | 1–4 |

| 7. This experience, with other parents of a child with chronic pain, helped me to feel more supported. | 4.31 (.74) | 2–5 | 4.00 (.83) | 2–5 | 4.42 (.61) | 3–5 | 4.30 (.64) | 3–5 | |

Open-ended Questions

Open-ended responses were coded (see Data Analysis section for details) and Kappa coefficients were calculated to assess level of inter-rater agreement. Kappa coefficient values ranged from .72–.74 revealing a good level of agreement between coders. When parents were asked what they would change about the group, most indicated that they would not change anything (59%). Parents were asked what they thought was the most helpful aspect of the group and the most frequent response was the group process (50.6%; e.g., being with other parents, sharing stories). Lastly, when parents were asked if their understanding of art therapy changed, most frequently parents reported that their understanding did change, indicating that they now were more open to art expression (50%). See Table 4 for open-ended question responses, categories, and frequency of responses.

Table 4.

Responses to Open-Ended Questions

| Theme | Example(s) | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Question 13: What would you change about today's group? Please describe what and why. (n= 59†) | |||

| None | “Nothing; Overall, I enjoyed it as it was.” | 35 | 59.3 |

| Session structure | “Shorten art piece/lengthen discussion.” | 14 | 23.7 |

| Session content | “Instead of writing a letter to yourself, write it to your child.” | 6 | 10.2 |

| “Maybe more psychology about releasing feelings and explanation of expression?” | |||

| Group-level comfort | “Group sharing, in general, is difficult for me.” | 4 | 6.78 |

| "Difficult with parents who are at different points, some kids just starting program, others finishing in same week.” | |||

| Question 14: What was the most helpful aspect(s) of today's group activity? (n= 75†) | |||

| Group process | “Being able to relax and be with other parents who understand the journey.” | 38 | 50.7 |

| “Having others add input and encouragement (supportive) to the original thoughts I expressed” | |||

| Opportunity for self-expression | “Expressing the emotions.” | 7 | 9.33 |

| “It was a good experience to express my feelings in another way.” | |||

| Art-making | “Being creative.” | 13 | 17.3 |

| “Using art to express your feelings” | |||

| Self-reflection | “Just thinking about my family and supporters” | 17 | 22.7 |

| Question 15: Through this group, has your understanding of art therapy changed? Why or why not? (n= 66†) | |||

| Yes | “Yes. Was easier and more relaxed than I thought.” | 33 | 50.0 |

| No | “No, I was familiar with how art therapy works.” | 22 | 33.3 |

| Overall positive feedback | “I'm appreciating the value of this more each time I participate.” | 9 | 13.6 |

| “Yes, was very nervous about art therapy, no experience but still learned and expressed feelings and overall was very helpful” | |||

| Unsure | “Not sure yet.” | 2 | 3.03 |

Note. Parents were asked to answer these questions at the end of each group session, thus there are a greater number of responses than parents in the sample.

Discussion

The journey of parenting and caring for a child with chronic pain is difficult, distressing, and often impacts caregivers emotional, physical, and psychological well-being, which in turn can inhibit their ability to provide optimal care for and respond to their child's needs while in pain. To better support parents of children with chronic pain in an intensive pediatric pain rehabilitation center, a four-module art therapy group intervention was developed and implemented. The art therapy modules selected sought to address several universal, thematic elements of a parent's experience caring for a child in chronic pain including feelings of fear, burden, isolation, and loss, as well as yearnings for support, hope, acceptance, and validation (Hunfeld et al., 2001; Jordan et al., 2007; Palermo & Eccleston, 2009). Art therapy was chosen as the basis for this intervention because of its inherent ability to facilitate discussion and expression of experiences that are otherwise difficult to communicate verbally (e.g. Malchiodi, 2012b), decrease anxiety and negative mood (e.g. Caddy et al., 2011) and build community (Liebmann, 2003). We evaluated the perceived helpfulness and satisfaction of the art therapy-based intervention in order to determine if this is an appropriate and valuable intervention to permanently include in the interdisciplinary treatment model.

Parent responses suggest that this treatment modality was well-received. Across all modules, parents enjoyed their experience in the art therapy group and found participation in the group to be feasible, regardless of artistic experience. As one parent reflected, “I was very nervous about art therapy, [with] no experience but still learned and expressed feelings and overall [the group] was very helpful.”

While we focused on evaluating the acceptability of an art therapy group for parents of children with chronic pain rather than evaluating its clinical efficacy, parent feedback suggests that it may have had a positive impact clinically as well. Parents indicated that the modules were helpful overall and reported that the group experience, in particular, helped them to feel more supported. Perceived social support is associated with a wide range of positive physical (Uchino, 2004, 2009) and mental health outcomes, including positive affect (Finch, Okun, Pool, & Ruehlman, 1999), lower rates of major depression (Lakey & Cronin, 2008), and lower levels of generalized psychological distress (Barrera, 1986; Cohen & Wills, 1985). Previous literature on the experiences of parents of children with chronic pain reflects parental feelings of helplessness, isolation, and a lack of validation (Jordan et al., 2007). It is promising that participation in the parent art therapy group appears to help address these clinical needs.

Limitations

Given that nearly three-quarters of participants were mothers, our results are more reflective of mother's responses to a parent art therapy group intervention than fathers. Often, for feasibility's sake, parents alternated weeks participating in the program with their child to attend to other responsibilities (e.g., work, other children) such that there was usually only one parent present at a time. This may account for why nearly half of participants only participated in one module, as over half of single module participants were from families where both parents participated. This characteristic of the program can make it especially difficult to establish group coherency, as most weeks there were new parents attending the group, even if there were no new patient admissions. Establishing group coherency is helpful in increasing perceived support and fostering an environment that is safe for sharing (Malchiodi, 2012b) and it is notable that parents reported feeling a sense of support within the group, despite this limitation.

It is also important to note that the pain rehabilitation program is not a cohort-based treatment model. Patients rotate in and out of the program at different times, meaning that parents complete the modules in different orders, while in different phases of their child's treatment. For this preliminary evaluation, modules were delivered in the same order each week, but our results suggest that it would be beneficial to pay consideration towards what phase of treatment the majority of group participants are in when choosing the module for the group.

Additionally, this intervention only includes four modules. There may be more relevant modules that were not included. Finally, while the modules were delivered as consistently and pragmatically as possible, the reality of clinical care is that some elements, environmentally, relationally, personally, logistically, cannot be controlled. When possible, differences in group characteristics were coded. It is unknown if these factors significantly impacted participant evaluation of the program.

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

Implementation of an art therapy group requires a master's level art therapist, at least one hour per week of time for the group session, sufficient private space with a table, and access to art materials. As the group was currently implemented, art therapy was provided once a week for an hour to parents and parents did not meet the facilitator until attending the group. Based on participant feedback, it could be beneficial to introduce the art therapist to the parents prior to initiation of group sessions. Additionally, it may be helpful to expand the current art therapy curriculum to include additional arts-based sessions throughout the week, perhaps involving the parent and child meeting together, as this was a format requested by multiple parents.

Some parents commented on the space constraints of the room and workspace where the group was held. Providing a space which is conducive for art making is crucial to the therapeutic process (McNiff, 2004; Malchiodi, 2007) and it would likely be worthwhile to consider and investigate the feasibility of holding the art therapy group in a larger space. Participants also commented on the timing of the group, that sometimes it felt rushed and requested more time for group sharing. One way to address this concern would be to administer the Satisfaction and Helpfulness survey separate from the conclusion of the group, so that completion of the measure would not take away from active group time. It is unknown why there were more parents late to the Letter to Future Self module than other modules

Numerous parents exhibited and verbalized anxiety about participating in the art therapy group, frequently making comments such as, “I'm not an artist, I can't even draw a stick figure” or “I don't even know what I'm getting myself into here!” before the groups began. After participating in the group, however, many parents were surprised to find out that art therapy was not as intimidating as they initially thought it would be. Perhaps expanding our introductory brochure to include parent testimonials may help to alleviate some of their anticipatory anxiety.

The overall feedback we received indicates that the parent art therapy group was a valuable, helpful, and enjoyable experience. In closely examining responses from the survey, however, parents reported that they were unsure if the groups helped them to understand something new regarding parenting of a child with chronic pain. This may be attributed to the fact that the modules of the group interventions were designed to be self- reflective, insight-oriented, and introspective in nature, encouraging parents to identify and explore their experience parenting a child with chronic pain and how their child's pain has impacted their life. Given that the current scope of the modules may not encompass translating these new insights into new parent practices, behaviors, or responses, it may be worthwhile exploring how additional modules could translate some of these insights into parenting behaviors. Research is emerging on the integration of cognitive behavior therapy and art therapy (e.g Malchiodi, 2012a; Pifalo, 2007). The benefits of such integration seem to be two fold in that cognition can inform and offer a framework to deepen, contain, and transform artistic experiences while non-verbal modalities can help to bridge a gap between cognition, emotions, and behavioral responses and more easily facilitate emotional exploration. For example, parents could be asked to create an image of how they feel internally when they witness their child in the midst of a pain flare accompanied by an image of how they respond externally to their child's pain. Parents could then be encouraged to brainstorm alternative ways to respond to their child's pain and the possible consequences of different responses. Dialogue and reflection about their images and proposed responses could be guided by psychoeducation about optimal parental responses to children's pain as well as teaching tools for self-regulation of parental responses in the face of children's pain. In this way, art making is used as a vehicle for self-reflection, problem solving, and group discussion. Utilizing such an integration in the parent art therapy groups, by incorporation of parenting skills training into the arts processes, could be particularly beneficial to parents, as evidence already exists to support the efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy with parents of children with chronic illness (Eccleston et al., 2012). Beyond parent skills training, given the high levels of distress that parents of children with chronic pain reportedly experience (e.g. Hunfeld at al., 2001), incorporating teaching and training of breathing, relaxation, and mindfulness-based components into the art therapy groups, as utilized with patients in the program, could also be beneficial.

In order to examine who may benefit the most from this modality of treatment and the potential impact of the groups on improving parent well-being, future studies should gather additional information regarding levels of parent psychological distress and parent approaches to coping. It would also be beneficial to examine if addressing parent pain-related distress in this manner impacts child outcomes.

Moving forward, feedback received from parents will be integrated to improve the parent art therapy group intervention. For example, the Letter to Future Self activity could be shortened so that more parents are able to finish and more time could be allotted for introductions and doing a group warm up activity (e.g. collaborative art making or “ice-breakers”) to foster stronger group coherency, particularly for activities like the Letter to Future Self where you write to other parents.

Conclusions

To conclude, perhaps the most promising of all results is that across all modules, regardless of ratings of difficulty, helpfulness, or enjoyment and displays of anxiety during the group, parents agreed that they would not only try art therapy again, but also would recommend the intervention to other parents of children with chronic pain. When making art, participants are empowered with options and given control over their experience through options of materials and modality of self-expression (Malchiodi, 2012b). Very literally, participants hold the art materials in their own hands and are in control of the marks that they make on the paper, offering them the liberty to convey and portray their experience in whichever way they choose-literally, abstractly, metaphorically, or cryptically- while monitoring their level of self-disclosure (Malchiodi, 2012b). As previously mentioned, this sense of control over one's experience is often lost when parenting a child with chronic pain and grappling with an inability to take away the pain (Jordan et al., 2007).

The needs of children with chronic pain and their families are complex. Clinicians need to rise to meet these challenges with interventions that are creative and diverse in nature. Presently, the need for better clinical care for parents of children with chronic pain is high and the existence of parent-only interventions for this population is sparse. Subsequently, parent's initial positive responses to art therapy holds the promise of innovative advancement in not only the fields of both art therapy and pediatric chronic pain management, but also the potential for more comprehensive, effective clinical care for children with chronic pain and their parents.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Veronica Gaughan, RN MSN, Charles Berde, MD PhD, Jennifer Brown, MA ATR-BC at Lesley University, Margaret Ryan, BA,& Gabi Barmettler, BA for their support of this research.

Funding: This investigation was supported by a K23 Career Development Award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development HD067202 (L.S.), the Sara Page Mayo Endowment for Pediatric Pain Research and Treatment, and the Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine at Boston Children's Hospital.

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Barrera M., Jr. Distinctions between social support concepts, measures and models. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1986;14:413–445. [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR. Development of a clinician based preventive intervention for families with affective disorder. Journal of Preventative Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1990;4:39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bell CE, Robbins SJ. Effect of art production on negative mood: A randomized, controlled trial. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association. 2007;24(2):71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan D. Moreno's social atom: A diagnostic and treatment tool for exploring interpersonal relationships. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 1984;11(3):155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Caddy L, Crawford F, Page AC. `Painting a path to wellness': correlations between participating in a creative activity group and improved measured mental health outcome. Journal of psychiatric and mental health nursing. 2012;19(4):327–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caes L, Veroort T, Eccleston C, Vandenhende M, Goubert L. Parental catastrophisizing about child's pain and its relationship with activity restriction: The mediating role of parental distress. PAIN. 2011;152:212–222. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Councill T. Art therapy with pediatric cancer patients. In: Malchiodi C, editor. Medical art therapy with children. Jessica Kingsley; Philadelphia, PA: 1999. pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Eccleston C, Crombez G, Scotford A, Clinch J, Connell H. Adolescent chronic pain: Patterns and predictors of emotional distress in adolescents with chronic pain and their parents. PAIN. 2004;108:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccleston C, Palermo T, Fisher E, Law E. Psychological interventions for parents of adolescents with chronic illness. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;8:1–131. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009660.pub2. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch J, Okun M, Pool G, Ruehlman L. A comparison of the influence of conflictual and supportive social interactions on psychological distress. Journal of Personality. 1999;67(4):581–621. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy A. Art therapy, research, and evidence- based practice. SAGE Publications; Oakland, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hunfeld J, Perquin C, Duivenvoorden H, Hazebroek-Kampschreur A, Passchier J, van Suijlekom-Smit L, van der Wouden J. Chronic pain and its impact on quality of life in adolescents and their families. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2001;26(3):145–153. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.3.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan A, Eccleston C, Osborn M. Being a parent of the adolescent with complex chronic pain: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. European Journal of Pain. 2007;11:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan F. Art, science, and art therapy: Repainting the picture. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; Philadelphia, PA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- King S, Chambers C, Huguet A, MacNevin R, McGrath P, Parker L, MacDonald A. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: systematic review. PAIN. 2011;152:2729–2738. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey B, Cronin A. Risk factors for depression. 2008. Low social support and major depression: Research, theory and methodological issues; pp. 385–408. [Google Scholar]

- Lenze E, Munin M, Quear T, Dew M, Rogers J, Begley A, Reynolds Iii C. The Pittsburgh Rehabilitation Participation Scale: reliability and validity of a clinician-rated measure of participation in acute rehabilitation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2004;85(3):380–384. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebmann M. Developing games, activities, and themes for art therapy groups. In: Malchiodi C, editor. Handbook of ART THERAPY. The Guildford Press; New York, NY: 2003. pp. 325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Logan D, Carpino E, Chiang G, Condon M, Firn E, Gaughan VJ, et al. A Day-hospital Approach to Treatment of Pediatric Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: Initial Functional Outcomes. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(9):766–74. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182457619. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182457619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan D, Scharff L. Relationships between family and parent characteristics and functional abilities in children with recurrent pain syndromes: An investigation of moderating effects on the pathway from pain to disability. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30:698–707. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malchiodi C. Cognitive- behavioral and mind-body approaches. In: Malchiodi C, editor. Handbook of ART THERAPY. 2nd edition The Guildford Press; New York, NY: 2012a. pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Malchiodi C. The art therapy sourcebook. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Malchiodi C. Using art therapy with medical support groups. In: Malchiodi C, editor. Handbook of ART THERAPY. The Guildford Press; New York, NY: 2012b. pp. 397–408. [Google Scholar]

- McNiff S. Art heals: how creativity heals the soul. Shambala; Boston, MA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer K, Shephard B. An art inquiry into the experiences of a family of a child living with a chronic pain condition: A case study. Canadian Journal of Counseling. 2008;42(1):7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Palermo T, Eccleston C. Parents of children and adolescents with chronic pain. PAIN. 2009;146:15–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo T, Putnam J, Armstrong G, Daily S. Adolescent autonomy and family functioning are associated with headache-related disability. Clin J Pain. 2007;23:458–65. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31805f70e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pifalo T. Jogging the cogs: Trauma-focused art therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy with sexually abused children. Art Therapy. 2007;24(4):170–175. [Google Scholar]

- Sieberg C, Williams S, Simons L. Do parent protective responses mediate the relations between parent distress and child functional disability among children with chronic pain? Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2011;36(9):1043–1051. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons LE, Claar RL, Logan DL. Chronic pain in adolescence: parental responses, adolescent coping, and their impact on adolescent's pain behaviors. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33(8):894–904. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szigethy E, Kenney E, Carpenter J, Hardy D, Fairclough D, Bousvaros A, DeMaso D. Cognitive- Behavioral therapy for adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease and subsyndromal depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(10):1290–1298. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180f6341f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons LE, Sieberg CB, Claar RL. Anxiety and impairment in a large sample of children and adolescents with chronic pain. Pain Research and Management. 2012;17(2):93–97. doi: 10.1155/2012/420676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. Social support and physical health: Understanding the health consequences of our relationships. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. Understanding the links between social support and physical health: A life-span perspective with emphasis on the separabil-ity of perceived and received support. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2009;4:236–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vowles K, Cohen L, McCraken L, Eccleston C. Disentangling the complex relations among caregiver and adolescent responses to adolescent chronic pain. PAIN. 2010;151(3):680–686. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh S, Culpepper Martin S, Schmidt L. Testing the efficacy of a creative-arts intervention with family caregivers of patients with cancer. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2004;3:214–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiksell RK, Greco LA. Acceptance and commitment therapy for pediatric chronic pain. In: Greco LA, Hayes SC, editors. Acceptance & mindfulness treatments for children & adolescents. New Harbinger Publications; Oakland, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]