Abstract

Against a backdrop of two new developments in the fertility behavior of the Mexican-Origin population in the U.S., the present discussion will update contemporary Mexican-Origin fertility patterns and address several theoretical weaknesses in the current approach to immigrant group fertility. Data come from six national surveys (three from Mexico and three from the U.S.) that cover a twenty-five year period (1975– 2000). The findings demonstrate dramatic decreases in the fertility rates in Mexico at the same time that continuous increases have been documented in the fertility rates of native-born Mexican-Americans in the U.S. at younger ages. These changes necessitate a reexamination of the idea that Mexican pronatalist values are responsible for the high fertility rates found within the Mexican-Origin population in the U.S. Instead, they point to the increasing relevance of framing the fertility behavior of the Mexican-Origin population within a racial stratification perspective that stresses the influence of U.S. social context on fertility behavior. As a step in this direction, the analysis examines fertility patterns within the Mexican-Origin population in the U.S., giving special attention to the role of nativity/generational status in contributing to within group differences.

1. Introduction

Interest in the fertility behavior of immigrants has enjoyed a resurgence in recent years, in large part due to concern over below replacement fertility and the aging population structures of many immigrant receiving-countries (Waldorf 1999). The potential rejuvenating effects of immigrant fertility are most pressing for the handful of European countries that are currently experiencing “lowest-low fertility” (Billari and Kohler 2004). Yet the scope of the impact of immigrant fertility is also likely to be large in the United States, where one immigrant group far outstrips all others in size, scope, and fertility levels.

Mexican immigration to the United States dominates the immigrant flow, making it the largest national-origin group immigrating to the U.S. over the last 25 years. Augmenting the sheer size of the flow, the higher and earlier fertility of Mexican-Origin women has the potential to translate into a considerable rejuvenating effect on the future U.S. population. 3 Previous population projects have estimated a cumulative contribution of Mexican-Origin fertility from the 1980s to 2040 of around 18 million births (Day 1996). A more recent analysis suggests that these projections may be significantly underestimated (Jonsson and Rendall 2004). Using an innovative method that makes the sending-country birth cohort the risk group upon which to project receiving-country childbearing, the revised projections put the cumulative contribution of Mexican-Origin fertility 100 percent higher, at 36 million births and estimate that by around 2031, the annual additional births contributed by Mexican-Origin women will rise to over one million per year (approximately one-quarter of today’s annual U.S. births).

In spite of the increasing relevance of Mexican fertility to the future demographic and social reality of the U.S. population, the fertility behavior of Mexican-Origin women remains poorly understood. The prevailing model is one of cultural adaptation which argues that first-generation Mexican immigrants come from a cultural environment in Mexico that reinforces and encourages adherence to traditional pronatalist norms (Rindfuss and Sweet 1977). These high reproductive norms and behaviors are then understood to be transferred to the U.S. via immigrants to re-create a pronatalist subculture that permeates the entire Mexican-Origin community (Marcum 1980). This process is said to be particularly strong for the Mexican-Origin population, whose migration trajectories are characterized by back and forth movement and a high level of contact with their origin communities (Carter 2000). As noted by Abma and Krivo (1991): “this flow of people and information [from Mexico] perpetuates sub-cultural pronatalist norms for individual Mexican immigrant families by reinforcing the influence of the norms and expectations of the origin society, and thereby weakening the effect of American fertility norms” (149). With time in the U.S. and greater assimilation into larger U.S. society, it is expected that a lessening of attachment to pronatalist norms will occur, and fertility levels will subsequently decrease.

The present analysis presents evidence that questions the validity of these two consistent components of the cultural adaptation model, namely that the higher and earlier fertility of Mexican-Origin women originates from attachment to pronatalist norms, and secondly, that time in the U.S. leads to lower fertility levels, as attachment to origin country norms decreases. In the concluding section, we point to the increasing relevance of framing the fertility behavior of the U.S. Mexican-Origin population within a racial stratification perspective that stresses the influence of the U.S. social context on fertility behavior.

2. Data and methods

The data for these analyses come from a series of national surveys from both Mexico and the U.S. The first analysis uses data from the U.S. vital statistics and estimations from the National Population Council of Mexico (CONAPO). The data for all subsequent analyses come from six different national surveys. In the case of Mexico, we use data from the 1975–1976 Encuesta Mexicana de Fecundidad (EMF), the 1986– 1987 Encuesta Nacional sobre Fecundidad y Salud (ENFES), and estimations from the National Council on Population (CONAPO) for the 1998–2000 period. For the U.S. analysis, we use the June Current Population Survey (CPS), which includes a fertility supplement. The survey years were chosen to match the Mexican sample years and they include the combined samples of 1975–1977, 1986–1988 and 1998–2000. In the second part of the paper, we take a closer look at the Mexican-Origin population in the U.S. and add data from the most recent 2002 CPS. In all cases, the weights provided by the EMF, ENFES and CPS were used so that each estimate is nationally representative for the respective country.

Following the descriptive results, we present the results of the regression models. When the outcome is dichotomous, i.e. whether or not a birth occurred, we use a logistic regression model. To estimate cumulative fertility, the outcome is a count variable measuring the number of children ever born and a Poisson regression model is used. As a first step towards addressing the possibility of changes over time in within-group fertility differentials, we include an analysis of the fertility patterns of the Mexican-Origin Population fifteen years earlier using data from the 1986–1988 June CPS. For all models, weights are used that adjust for the sampling design of the CPS. Models are run in Stata 8.1.

3. Measurement

Comparisons of fertility behavior are highly contingent on age, parity and timing of migration. It has been suggested that women who recently migrated to the U.S. may display higher current fertility as they attempt to catch-up after they migrate. However, this effect might not appear in a measure of cumulative fertility, which captures a woman's complete childbearing history. As a result, we include two measures of fertility that capture current fertility behavior as well as cumulative fertility behavior. Every survey examined here contained a specific fertility component that collected information on the number of children born to each woman between the ages of 15–44 as well as the date of birth of her last child. 4 As a measure of cumulative fertility, the number of children ever born to each respondent is used. For current fertility, we use the occurrence of a birth in the year prior to the survey.

The second part of the analysis involves differentiating the Mexican-Origin population by nativity and generational status. Subdividing the Mexican-Origin population allows us to determine if more time in the U.S. results in lower fertility and if this is an effect that continues to operate even among the native-born generation, i.e. from the second- to third-generation. In the 1998–2002 CPS June surveys, information was obtained on year of immigration and country of birth of individuals and their parents, allowing for the construction of detailed immigrant categories. For foreign-born immigrants, we differentiate by duration since immigration, which has been shown to influence fertility patterns among immigrant women (Andersson 2004; Ford 1990). Several studies have found evidence of a fertility promoting effect, so that immigrants exhibit elevated birth risks shortly after migration, likely due to the link between migration and family building (Andersson 2004; Ford 1990; Ng and Nault 1997). Other studies have hypothesized a pre- or post-disruption effect, i.e. women may delay fertility in anticipation of migration or as a result of migration and then increase their fertility at some point shortly afterwards in an effort to “catch-up” for the disruption (Carter 2000; Stephen and Bean 1992). The CPS provides information on year of arrival in two year groupings. In the descriptive figures, we distinguish foreign-born Mexican-Origin women by whether they had been in the country for more or less than 6 years. In the regression models, we place foreign-born Mexican-Origin women into one of 4 groups, which roughly correspond to 5-year groupings for duration of stay (≤6, 7–11, 12–16 and 17+ years). Neither of these categorizations allow us to distinguish between very short-term effects of migration on fertility, i.e. the difference between catch-up fertility caused by disruption and/or family building linked to migration. But they do permit us to examine whether there are short-term and/or long-term effects of duration on immigrant fertility, and if these effects operate in the direction proposed by the cultural adaptation model, i.e. a convergence over time to the fertility levels prevailing in the U.S.

The native-born population is differentiated by generation. Adaptation to the norms and behaviors of the host country population is often a process that occurs over a period of successive generations. By distinguishing the native-born by generation we are able to investigate the possibility of more gradual patterns of adaptation. The second-generation is defined as consisting of Mexican-Origin women who were born in the United States or abroad to an American parent and who reported that at least one parent was born in Mexico. Women are classified as belonging to the third-or-later-generation if they were born in the U.S. or abroad and also reported that both of their parents were born in the U.S.

In the regression models, a sub-set of basic predictors is included. With regard to the demographic variables, maternal age is coded into the age-group categories common to fertility analyses: 15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44. In the descriptive statistics parity status is given by four categories: childless, one child, two children, three or more children. In the regression model predicting a birth in the previous year, parity status refers to the respondent’s status in the year prior to the survey and is kept continuous in the analysis. Marital status was measured at the time of the survey and differentiates between women who are married and those who are not. Women who reported that they were cohabiting at the time of the survey are categorized as belonging to the ‘wed’ category. With regard to the socioeconomic indicators, education is coded into four different categories. In order to account for the possibility that some of the women, particularly the younger women, have not yet finished school, a category was created for respondents who reported that they were currently enrolled in school at the time of the survey. Those respondents who were not enrolled in school at the time of the survey are differentiated by whether or not they completed high school or some level of college. Home ownership is coded to indicate if the house in which the respondent lived at the time of the survey was owned or rented. Finally, total household income is categorized into quartiles, with the highest quarter as the reference.

4. Findings

4.1 Mexico and the U.S

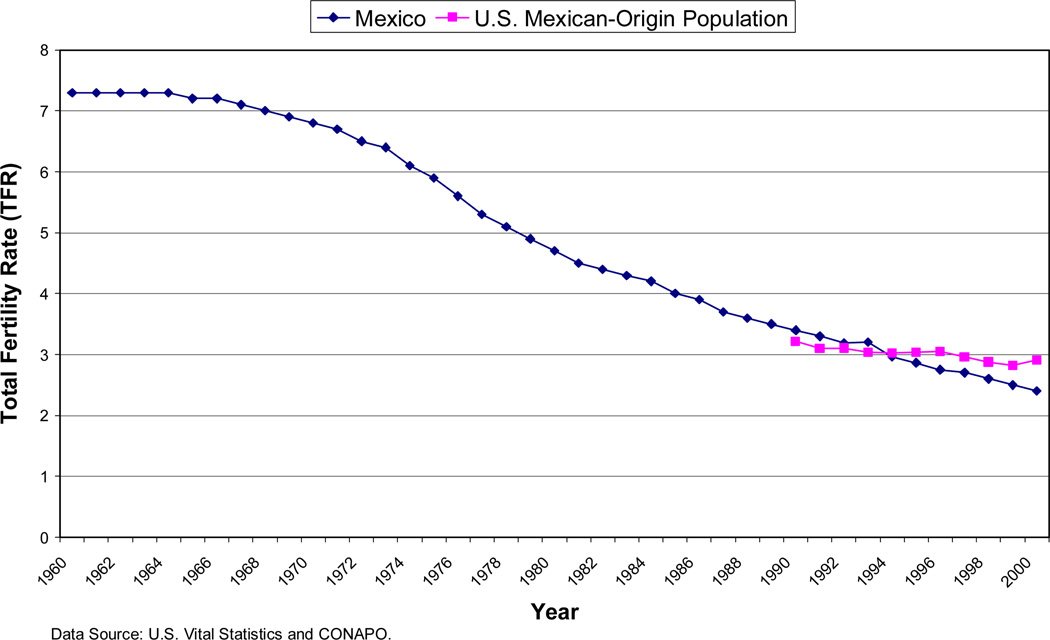

Figure 1 presents trends in the total fertility rate (TFR) for both Mexico and the U.S. Turning first to the case of Mexico, it is clear from the graph that the country has experienced spectacular decreases in the fertility behavior of its population, with the TFR dropping from a high of 7.3 births per women in 1960 to 2.4 in 2000. Heralded as Mexico's silent revolution, the beginning of the most intense decrease in fertility occurred in the mid-1970s (CONAPO 1999). This corresponds to the introduction in 1974 of a new population policy by the Mexican government, which resulted in a steep rise in contraceptive prevalence. The fact that the fertility decline began so soon after the official family planning program started suggests that the demand for children had already fallen. Although varying in its speed and intensity, the monotonic decline in Mexico's TFR has continued to this day. The fertility decline in Mexico provides a clear rebuke to the idea, very prevalent in U.S.-based research on immigration, that the country of origin remains statically traditional; an unchanging world where cultural systems are passed from generation to generation. In the case of fertility, this assumption ignores the rapid and dramatic demographic changes that have recently taken place in Mexico.

Figure 1.

Total Fertility Rates for Mexico and the U.S. Mexican-Origin Population

The extent of the drop in Mexico's TFR becomes even more apparent when we turn our attention to the Mexican-Origin population in the U.S. Data is shown beginning in 1990, when almost all states began reporting Hispanic Origin on the birth certificates. 5 Comparing the Mexican-Origin population in the U.S. with women in Mexico, we see evidence for a crossover between Mexican fertility and Mexican-Origin fertility in the U.S. At the beginning of the 1990s the Mexican TFR was still higher than the TFR of Mexican-Origin women in the U.S. But beginning in 1994, the TFR for Mexican-Origin women became higher than the TFR for women in Mexico. For the rest of the 1990s, the gap between the two population groups increased, as the Mexican TFR continued to fall and the TFR for Mexican-Origin women remained constant, only decreasing slightly beginning in 1997. By 2000, the TFR in Mexico was reported to be 2.4 and the TFR for Mexicans in the U.S. was 2.9, a half child greater. This discrepancy in rates calls into question the model of immigrant fertility that has formed the basis of virtually every study of Mexican-American fertility, i.e. a pattern by which women move from a high fertility to a low fertility context. It appears that a woman moving from Mexico to the U.S. today is actually moving from a lower fertility context into a higher fertility context, at least to the extent that she becomes integrated into the Mexican-Origin community in the U.S.

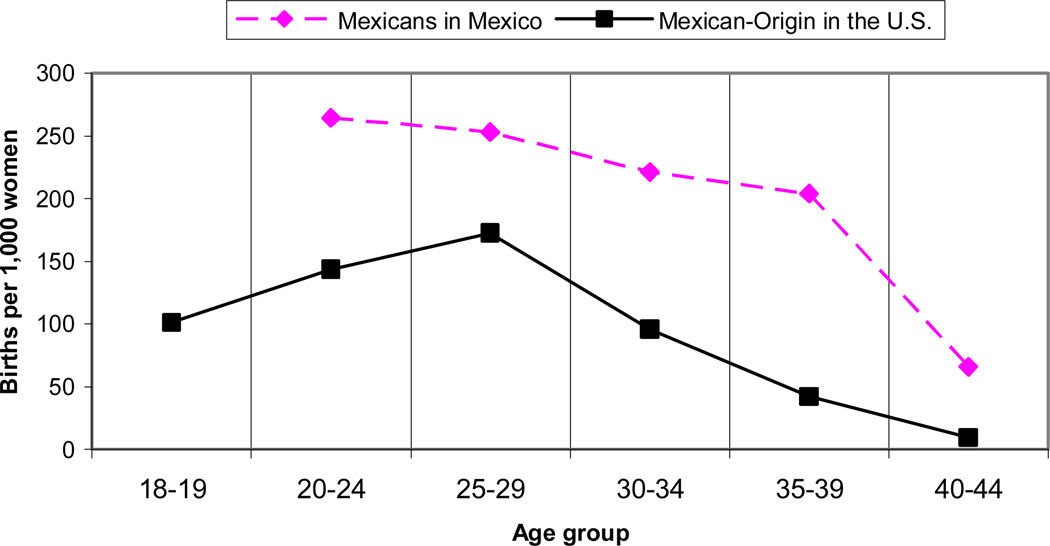

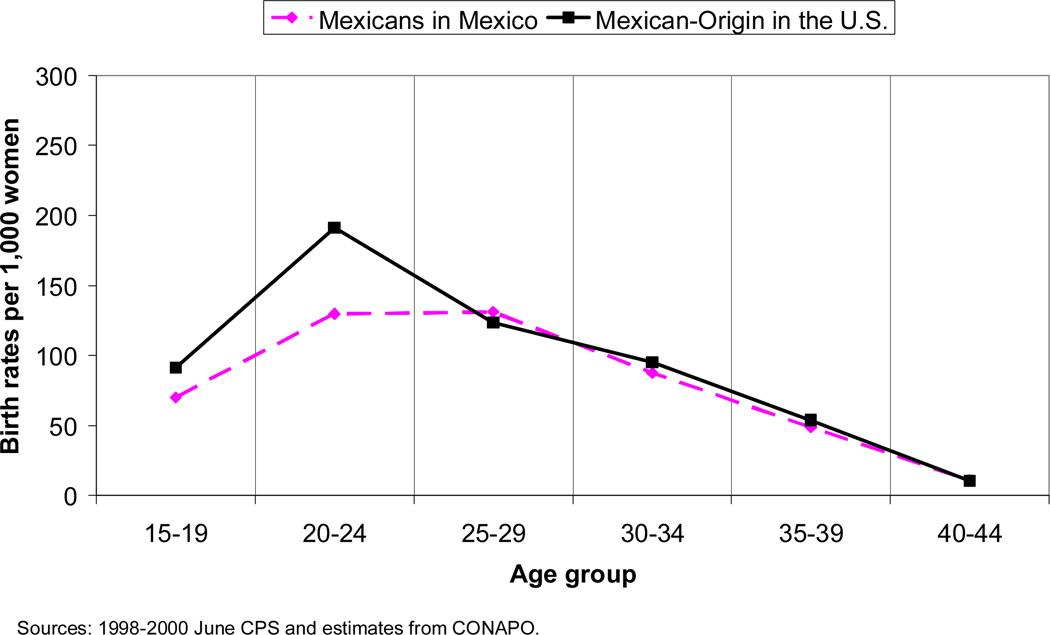

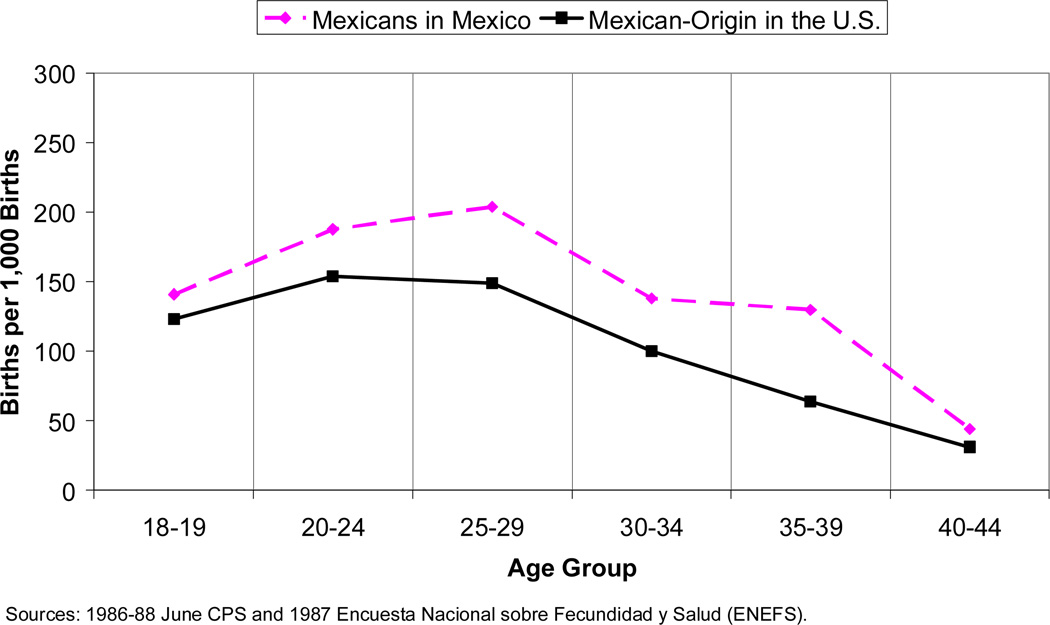

Figures 2–4 present the age-specific fertility rates for the Mexican-Origin population in the U.S. and Mexican women residing in Mexico over the last 25 years. Beginning with Mexico, the 1975–1977 period comes directly after the implementation of the country’s first family planning program. 6 As a result, the country continues to be characterized by high fertility levels for every age group, including the older ages. In contrast, Mexican-Origin women in the U.S. display considerably lower fertility rates at every age group. Figure 3 presents the same birth rates ten years later for the 1986– 1988 time period. For Mexico, this time period corresponds to the time after the most rapid declines in the late 1970s. Accordingly, every Mexican age-group exhibits considerably reduced fertility rates as compared to 10 years earlier. In contrast, the data for the Mexican-Origin population in the U.S. show an increase in the fertility rates of teens and young women (ages 18–24) and also for older women (30–44). Figure 4 presents the age-specific fertility rates for the most recent period (1998–2000) which presents the crossover identified in Figure 1. 7 Mexican women in Mexico continue to exhibit fertility declines across every age group while Mexican-Origin women in the U.S. continue to exhibit increases in fertility for younger women. In the most recent period, the most pronounced differences in fertility rates between the two origin groups occur at the younger ages.

Figure 2.

Age-Specific Fertility Rates, Mexico and the U.S. 1975–1977

Figure 4.

Age-Specific Fertility Rates, Mexico and the U.S. 1998–2000

Figure 3.

Age-Specific Fertility Rates, Mexico and the U.S. 1986–1988

4.2 The Mexican-Origin population in the U.S

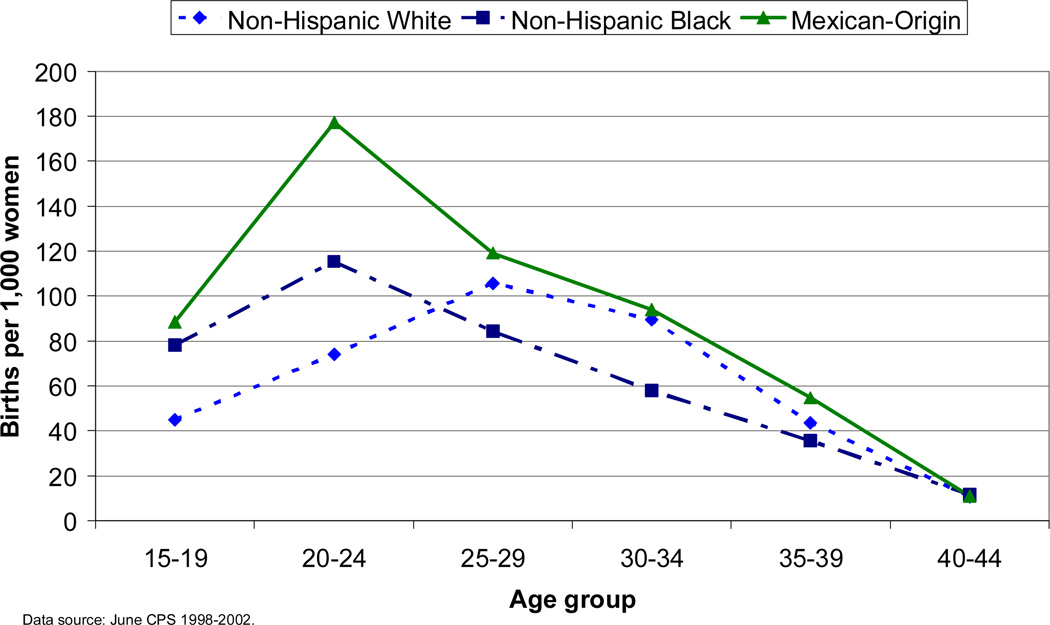

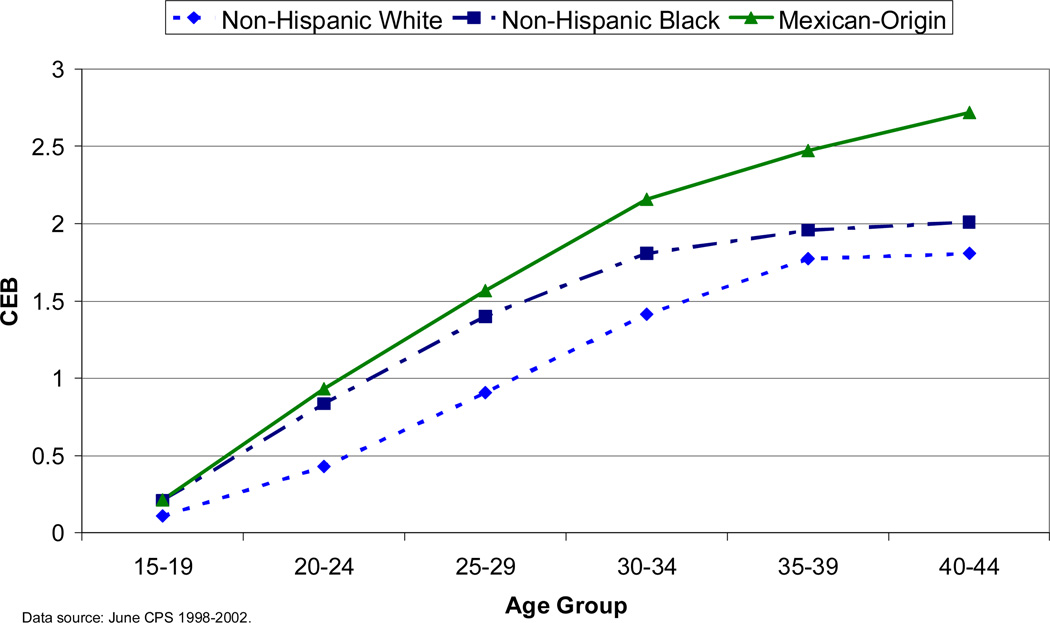

The high fertility rates of the Mexican-Origin population in the U.S. are even more pronounced when placed in the U.S. context in Figure 5. As compared to non-Hispanic Whites and non-Hispanic Blacks, Mexican-Origin women demonstrate higher fertility rates for every group except the very oldest. Interestingly, Mexican-Origin and non-Hispanic Black women appear to display similar patterns of fertility at the early ages. But while Mexican-Origin women continue to exhibit high rates throughout their reproductive lives, the fertility rates of non-Hispanic blacks drop below those of non-Hispanic Whites beginning in the 25–29 age group. As a result, Figure 6 demonstrates that the higher current fertility of Mexican-Origin women translates into considerably higher completed fertility, but non-Hispanic Black women have estimates of completed fertility that are similar to estimates for non-Hispanic Whites.

Figure 5.

Age-Specific Fertility Rates by Race/Ethnic Group (15–44)

Figure 6.

Average Children Ever Born (15–44)

4.3 The Mexican-Origin population disaggregated

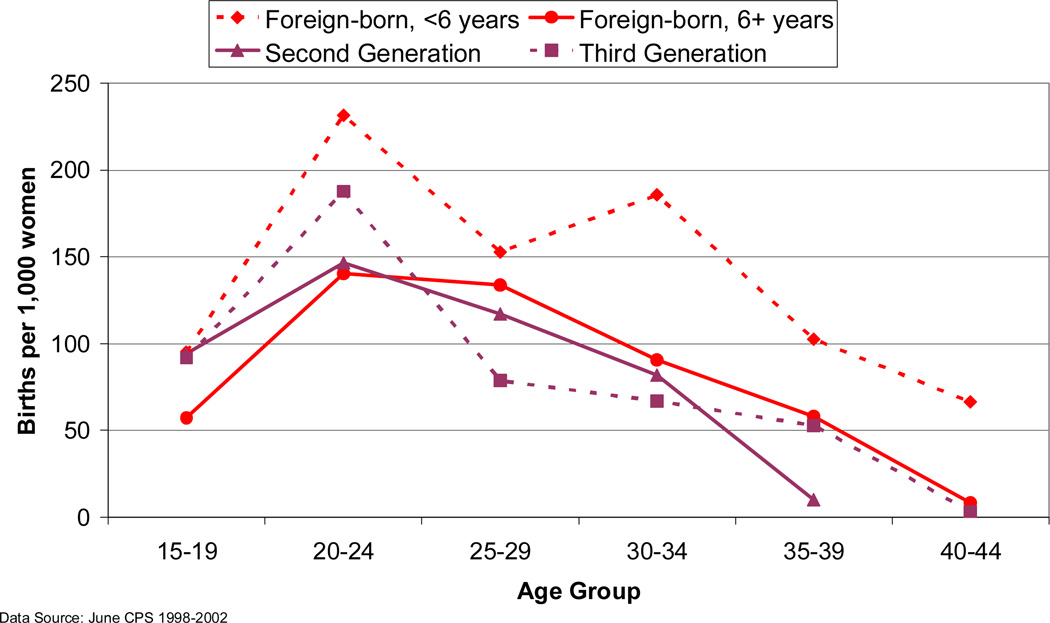

Mexican immigrants have had a long history of migration to U.S. and they continue to post high rates of current immigration. As a result, the Mexican-Origin population in the U.S. boasts considerable generational depth at the same time that it is characterized by a high number of foreign-born immigrants. Figure 7 differentiates the foreign-born Mexican-Origin sample by nativity and time since migration, which allows us to account for the possibility that timing of the migration act may influence fertility levels for women born in Mexico. We differentiate the native-born population by their generation status.

Figure 7.

Mexican-Origin Fertility Rates by Nativity/Gener. Group

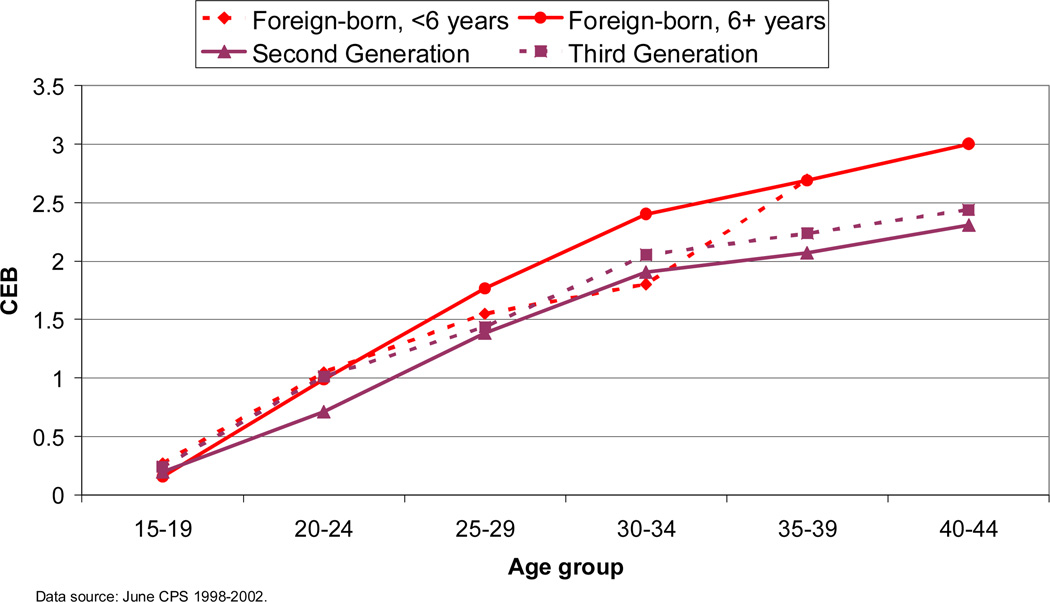

Foreign-born immigrants who have spent 6 years or less in the U.S. display the highest fertility levels across all ages. Foreign-born women who have been in the U.S. for more than 6 years, have uniformly lower fertility rates than more recent immigrants. Yet once we look at both the foreign-born and native-born groups conjointly, we do not see linear decreases across the age groups by nativity. At the youngest ages, U.S.-born second- and third-generation women have fertility rates that are noticeably higher than women who were born in Mexico and who spent more than 6 years in the U.S. This pattern of high fertility continues for U.S.-born third-generation women in the 20–24 age group, so that their fertility is closer to recent immigrants than to the other two groups. For the younger age groups, greater time in the U.S. and a move from the second- to the third-generation does not appear to be associated with a linear decrease in fertility levels, especially for the third-generation of U.S.-born women. The fertility pattern of third-generation women is remarkably similar to the one presented for African-American women in Figure 6, where they begin their reproductive lives with very high fertility rates at younger ages but then drop below the other sub-groups in the older ages. Beginning with the 25–29 age group, the pattern of a linear decrease across the four Mexican-Origin sub-groups eventually appears, so that foreign-born women with 6 years or less in the U.S. have the highest fertility rates, followed by foreign-born women with more than 6 years in the U.S., followed sequentially by the two native-born groups. Figure 8 demonstrates that the higher current fertility of foreign-born Mexican-Origin women translates into considerably higher completed fertility at the end of their reproductive lives, with virtually no difference by duration in the U.S. But among the U.S.-born groups, we see a reversal of position so that third-generation women have higher completed fertility than second-generation women.

Figure 8.

Mexican-Origin Mean CEB by Nativity/Generational Group

The figures suggest that a linearly decreasing pattern of fertility with time in the U.S. and across generational groups is particularly ill-fitting for the younger age groups, with native-born Mexican-Origin women posting high fertility levels at younger ages. These trends indicate that there are important differences in the life experiences of the Mexican-Origin sub-groups that contribute to differential fertility. Table 1 presents the percent distribution of several demographic and socioeconomic variables available in the CPS 1998–2002 for all non-Hispanic White and Mexican-Origin women ages 15–44, regardless of their fertility status. Comparing non-Hispanic whites and the Mexican-Origin population (columns 1 and 2), the latter population is considerably disadvantaged along the socioeconomic indicators. Over 40 percent of the Mexican-Origin population did not complete high school whereas only 14 percent of the non-Hispanic white population failed to do so. Mexican-Origin women also have lower mean household incomes and a higher prevalence of living in rented quarters than non-Hispanic whites.

Table 1.

Percent distribution of predictor variables by generation/nativity group for Mexican-American for Mexican-Origin women. Ages [15–44]

| Mexican-Origin |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foreign-born | Native-born | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White |

Mexican-Origin | ≤6 yrs in U.S. |

6+ yrs in U.S. |

2nd Generation |

3rd Generation |

||

| Mean Age | 30.4 | 28.6 | 26.6 | 31.7 | 24.7 | 28.9 | |

| Parity | |||||||

| No Children | 45.0 | 33.8 | 33.3 | 20.2 | 52.1 | 35.5 | |

| 1 | 16.9 | 18.6 | 25.1 | 16.9 | 18.7 | 17.4 | |

| 2 | 23.3 | 21.1 | 20.6 | 23.1 | 14.8 | 23.6 | |

| 3 | 14.8 | 26.5 | 21.0 | 39.8 | 14.4 | 23.5 | |

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Unwed | 49.1 | 48.8 | 41.0 | 32.7 | 67.8 | 56.1 | |

| Wed | 50.9 | 51.2 | 59.1 | 67.3 | 32.2 | 43.9 | |

| Education | |||||||

| Currently Enrolled | 4.1 | 6.1 | 4.2 | 2.9 | 12.0 | 6.1 | |

| <12 years | 14.3 | 44.5 | 63.8 | 59.4 | 32.2 | 28.6 | |

| 12 years | 27.7 | 25.1 | 21.3 | 22.0 | 24.1 | 31.1 | |

| 12+ years | 53.8 | 24.3 | 10.8 | 15.8 | 31.7 | 34.2 | |

| Mean HH income | 55,419 | 34,153 | 26,357 | 29,860 | 37,409 | 39,889 | |

| Living quarters | |||||||

| Rented | 28.9 | 52.1 | 76.3 | 55.2 | 39.7 | 47.1 | |

| Owned | 71.1 | 47.9 | 23.7 | 44.8 | 60.3 | 52.9 | |

| (N) | 59852 | 5964 | 858 | 2016 | 1292 | 1798 | |

Data Source: 1998–2002 June CPS.

Columns 3–6 differentiate the Mexican-Origin population by nativity and generational status. Of the foreign-born women, recent immigrants are more likely to be unwed (41 percent) as compared to women who migrated more than 6 years ago (33 percent). Over two-thirds of second-generation women are unwed and over half of third-generation women were not married or cohabiting at the time of the survey. With regard to the socioeconomic indicators, we observe a linear decrease in the percentage of women without a high school education, so that among recent foreign-born immigrants, almost two-thirds lack a high school education, whereas only one-quarter of third-generation women do. The same pattern holds for mean household income, with a linear increase with more time in the U.S. and across generations. However, in most cases the differences between the two native-born groups are minor. While there appear to be considerable improvements from foreign-born immigrants to second-generation women, there are only relatively small changes between second- and third-generation Mexican-American women in both education and mean household income. In fact, there is an increase in the number of third-generation women who rent their home as compared to the second-generation. These patterns may indicate limited upward mobility from one native-born generation to the next. Another possibility involves selective ethnic self-identification, whereby more advantaged Mexican-Americans cease to identify themselves as such in the third-generation (Duncan and Trejo 2004). We are unable to address this possibility directly but do note that whatever the true differences between second- and third-generation Mexican-Americans, they occur in a context of considerable differences in socioeconomic attainment between both groups and non-Hispanic whites.

Table 2 presents the percent distribution for the same set of variables but limits the sample to women who had a birth in the year prior to the survey. Most remarkable is the pattern in non-marital fertility. Native-born Mexican-Origin women are considerably more likely to be unwed women giving birth in the last year. By the third-generation, over 50 percent of the women giving birth in the year prior to the survey are unwed. 8 In comparison, only 19 percent of foreign-born who migrated over 6 years ago and who gave birth in the previous year are unwed. Comparing foreign-born and native-born groups, we see that with time in the U.S., Mexican-American women demonstrate a de-coupling of childbearing and marriage. This is a trend that is becoming increasingly characteristic of U.S. women in general, and is particularly pronounced among African-American women. Third-generation women having a child in the previous year also have slightly lower mean household incomes than their counterparts in the second-generation and are more likely to rent their homes than own them. Again, there are very slight differences between the second- and third-generation in terms of having completed high school, distributions that point to the very limited mobility that has occurred across generations for the Mexican-Origin population.

Table 2.

Percent distribution of predictor variables for all women ages [15–44] who had a birth in the year prior to the survey

| Mexican-Origin |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foreign-born | Native-born | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White |

Mexican-Origin | ≤6 yrs in U.S. |

6+ yrs in U.S. |

2nd Generation |

3rd Generation |

||

| Mean Age | 28.1 | 25.6 | 25.8 | 28.5 | 22.8 | 24.8 | |

| Parity | |||||||

| First birth | 39.6 | 40.1 | 43.8 | 33.1 | 51.2 | 34.7 | |

| Second birth | 34.8 | 29.4 | 28.4 | 25.9 | 25.1 | 37.6 | |

| Third birth or higher | 25.6 | 30.5 | 27.8 | 41.0 | 23.7 | 27.7 | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Unwed | 25.4 | 35.9 | 26.2 | 18.9 | 48.3 | 52.3 | |

| Wed | 74.6 | 64.1 | 73.8 | 81.1 | 51.7 | 47.7 | |

| Education | |||||||

| Currently Enrolled | 3.0 | 5.2 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 11.7 | 8.1 | |

| <12 years | 12.8 | 47.0 | 63.6 | 58.3 | 31.4 | 33.4 | |

| 12 years | 27.0 | 27.9 | 25.2 | 24.4 | 29.1 | 33.0 | |

| 12+ years | 57.2 | 19.9 | 10.5 | 16.4 | 27.8 | 25.5 | |

| Mean HH income | 53,474 | 30,374 | 22,946 | 27,057 | 36,491 | 35,440 | |

| Living quarters | |||||||

| Rented | 31.2 | 57.3 | 72.7 | 57.4 | 43.0 | 55.8 | |

| Owned | 68.8 | 42.7 | 27.3 | 42.6 | 57.0 | 44.2 | |

| (N) | 3451 | 553 | 140 | 151 | 124 | 138 | |

Data Source: 1998–2002 June CPS.

In order to simultaneously incorporate the diverse demographic and socioeconomic factors that influence fertility decisions, the next table presents the results from a logistic regression equation modeling the odds of having a birth in the last year. The results are presented as odds ratios in Table 3. Model 1 includes only the nativity/generational effects and Model 2 controls for age. The results demonstrate that most of the Mexican-Origin sub-groups present significantly increased risks of having a birth in the year prior to the survey as compared to non-Hispanic white women. Among foreign-born women, there is a linear decrease in the risk of a recent birth with more time in the U.S. But once we control for age, instead of a linear decrease as one moves onto the native-born groups, second-generation women have higher odds of a recent birth than foreign-born women who have lived in the U.S. for more than 6 years. Adjusting for the demographic and socioeconomic factors, the same pattern remains so that within nativity groups, there is a decrease in differentials with time in the U.S. and between generations, but across nativity groups, we see that native-born women exhibit increased odds of a recent birth as compared to foreign-born women with more than 6 years in the U.S.

Table 3.

Results of Logistic Regression Models of Current Fertility by Nativity/Generation Group [Ages 15–44]. Coefficients are presented as odds ratios.

| Birth in last year | Birth in last year | Birth in last year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted1 | Adjusted2 | |

| Nativity/Generation of Mexican-Origin Population | |||

| [Non-Hispanic White] | |||

| Foreign-born, ≤6years | 3.143*** | 2.510*** | 1.798*** |

| Foreign-born, 7–11 years | 1.836** | 1.461* | 1.085 |

| Foreign-born, 12–16 years | 1.438* | 1.256 | 1.059 |

| Foreign-born, 17+ years | 1.074 | 1.197 | 1.088 |

| 2nd Generation | 1.712*** | 1.531*** | 1.563*** |

| 3rd Generation | 1.443*** | 1.381*** | 1.398*** |

| (N) | 65787 | 65787 | 65787 |

Data Source: 1998–2002 June CPS.

Adjusted for age.

Adjusted for age, marital status, home ownership, education, household income and birth order.

Table 4 presents the results from a Poisson regression modeling the number of children ever born. The estimates of children ever born are highly dependent on group differences in age profiles. Model 2 controls for age and demonstrates that for foreign-born women, there are linear increases in the differentials with time in the U.S. Among the native-born groups, a different pattern appears whereby third-generation Mexican-American women exhibit differentials of cumulative fertility that are higher than second-generation women. As a result, a curvilinear pattern emerges whereby the differential between the Mexican-American sub-groups and non-Hispanic whites increases in the third-generation. Controlling for the socioeconomic and demographic factors in Model 3, differences in the predicted number of children ever born decrease across all of the groups as compared to non-Hispanic whites, which likely illustrates the negative socioeconomic profiles characterizing the Mexican-Origin subgroups.

Table 4.

Results of Poisson Regression Model of Children Ever Born by Nativity/Generational Group [Ages 15–44]. Coefficients are exponentiated and expressed as incidence rate ratios (IRRs)

| Children Ever Born Unadjusted |

Children Ever Born Adjusted1 |

Children Ever Born Adjusted2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Nativity/Generation of Mexican-Origin Population | |||

| [Non-Hispanic White] | |||

| Foreign-born, ≤6years | 1.274*** | 1.673*** | 1.141*** |

| Foreign-born, 7–11 years | 1.621*** | 1.771*** | 1.196*** |

| Foreign-born, 12–16 years | 1.892*** | 1.685*** | 1.174*** |

| Foreign-born, 17+ years | 2.088*** | 1.659*** | 1.238*** |

| 2nd Generation | 0.879*** | 1.385*** | 1.303*** |

| 3rd Generation | 1.320*** | 1.468*** | 1.347*** |

| (N) | 65787 | 65787 | 65787 |

Source: 1998–2002 June CPS.

Adjusted for age.

Adjusted for age, marital status, home ownership, education, and household income.

Several anomalous patterns emerge from the regression models. Most notable are the differences in the estimates of current and cumulative fertility by sub-group. For example, the linearly decreasing risk of current fertility for foreign-born women with more time in the U.S. does not correspond to the finding of increased estimates of cumulative fertility with time in the U.S.—long term immigrants have the highest differential in the number of children ever born as compared to non-Hispanic whites. With cross-sectional data, it is difficult to appropriately account for why patterns of cumulative fertility are so different from patterns of current fertility. Longitudinal data with complete birth histories would allow us to track the parity-specific birth behavior of these women and help to elucidate the age, period, or cohort effects influencing their fertility. Lacking such data, another possibility is to compare the current snapshot of the fertility behavior of Mexican-Origin women to the fertility behavior of Mexican-Origin women at an earlier point in time. Tables 5 and 6 present the results from regression models predicting current fertility behavior and children ever born for women from approximately fifteen years earlier (1986–1988 June CPS). There are only two differences in the data between the two time periods. The 1986 and 1988 surveys only obtained fertility information for women between the ages of 18–44. Second, we collapsed two of the duration of stay categories in order to ensure sufficient n sizes.

Table 5.

Results of Logistic Regression Models of Current Fertility by Nativity/Generation Group [Ages 18–44] for 1986–1988. Coefficients are presented as odds ratios

| Birth in last year | Birth in last year | Birth in last year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted1 | Adjusted2 | |

| Nativity/Generation of | |||

| Mexican-Origin Population | |||

| [Non-Hispanic White] | |||

| Foreign-born, ≤6years | 1.994*** | 1.680** | 0.959 |

| Foreign-born, 7–11 years | 2.356*** | 1.978* | 1.100 |

| Foreign-born, 12+ | 1.942*** | 2.184*** | 1.738* |

| 2nd Generation | 1.627*** | 1.505* | 1.629* |

| 3rd Generation | 1.829*** | 1.614*** | 1.536*** |

| (N) | 49749 | 49749 | 49749 |

Data Source: 1986–1988 June CPS.

Adjusted for age.

Adjusted for age, marital status, home ownership, education, household income and birth order.

Table 6.

Results of Poisson Regression Model of Children Ever Born by Nativity/Generational Group [Ages 18–44] for 1986–1988. Coefficients are exponentiated and are expressed by incidence rate ratios (IRRs)

| Children Ever Born | Children Ever Born | Children Ever Born | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted1 | Adjusted2 | |

| Nativity/Generation of Mexican-Origin Population | |||

| [Non-Hispanic White] | |||

| Foreign-born, ≤6years | 1.105 | 1.436*** | 1.072 |

| Foreign-born, 7–11 years | 1.732*** | 2.049*** | 1.479*** |

| Foreign-born, 12+ | 2.003*** | 1.753*** | 1.330*** |

| 2nd Generation | 1.064 | 1.217*** | 1.149** |

| 3rd Generation | 1.342*** | 1.556*** | 1.310*** |

| (N) | 49749 | 49749 | 49749 |

Source: 1986–1988 June CPS.

Adjusted for age.

Adjusted for age, marital status, home ownership, education, and household income.

Important for the comparison of differentials between the two periods is the fact the fertility of the non-Hispanic white population remained virtually unchanged over the time period examined. Comparing estimates of current and cumulative fertility for women in the current period (Tables 3 and 4) with those for women from 15 years earlier (Tables 5 and 6), we observe decreases in the fertility differentials for almost all of the Mexican-Origin sub-groups as compared to non-Hispanic whites. One exception is for recent immigrants. The fertility differential between recent immigrants and non-Hispanic whites has increased over the last 15 years, for measures of both current and cumulative fertility. With regard to within group trends, the models of cumulative fertility for foreign-born women demonstrate a similar pattern in both periods, whereby time in the U.S. is associated with a linear increase in the fertility differential as compared to non-Hispanic whites. The only exception is in the earlier data, where women who have lived in the U.S. for over 12 years do not display as great a differential in cumulative fertility as those who lived in the U.S. for less than 12 years, once we control for age.

The trends in the current fertility of foreign-born women are more variable between the two periods. In the earlier period, longer duration in the U.S. was associated with an increased risk of current fertility. This is opposite the pattern in the more current period where longer duration in the U.S. is associated with a decreased risk of current fertility. With regard to the native-born population, there are several changes from the earlier period to the current one. As compared to second-generation women, third-generation women in the earlier period had a higher risk of a recent birth and higher cumulative fertility as compared to non-Hispanic whites. But in the 15 years since, third-generation women have decreased their risk of a current birth so that now it is lower than the second-generation risk. Third-generation women still have higher estimates of cumulative fertility than second-generation women but this differential has decreased over time. We also observe a slight increase in the differential for the estimated children ever born between second-generation Mexican-Origin women and non-Hispanic white women.

5. Discussion

Past studies have continuously invoked the key role of pronatalist values emanating from Mexico to explain the high rates of fertility found among Mexican-Origin women and particularly among foreign-born women. A comparison of the fertility rates of Mexican women in Mexico and Mexican-Origin women in the U.S. illustrates that currently, Mexican-Origin women in the U.S. demonstrate higher levels of overall fertility. In large part, this crossover is due to the dramatic fall in Mexico's fertility levels, which corresponds closely to the introduction of the country's first family planning program. But the crossover is also due to several key changes in the fertility behavior of the Mexican-Origin population in the U.S., including increases in the fertility of recent immigrants and of younger native-born Mexican-Origin women. We have argued that these changes demonstrate the decreasing relevance of pronatalist values as the basis for understanding the fertility behavior of the Mexican-Origin population, a point that is made clearer when we review the evidence presented in the previous sections.

5.1 The Foreign-Born Mexican-Origin population

In the current period, recent immigrants post higher fertility rates than every other Mexican-Origin sub-group at every age. This pattern is unlikely to reflect higher fertility norms coming from Mexico, as fertility levels have fallen lower in Mexico than among Mexican-Origin women here in the U.S. Instead, the higher current fertility of recent immigrants is consistent with previous work that has documented elevated fertility rates among recent immigrants across many different countries. With time in the host country, the risk of current fertility usually falls for foreign-born groups. The most common explanation behind these trends is that immigration is related to family building, so that the short-term effects of migration are to increase fertility levels but that with time in the host country, fertility falls. In the case of foreign-born women in Sweden, Andersson (2004) finds that migration is associated with a “stimulating fertility effect” for first birth and higher-order births. But after a period of approximately five years, the fertility of recent immigrants in Sweden did not deviate much from that of the native-born population. In the case of the Mexican-Origin population, earlier research has also suggested the possibility of a disruption effect, so that the act of immigration may force women to interrupt their childbearing. Once they arrive to the U.S. they quickly begin to make-up for the delay. This possibility may be particularly relevant for Mexican-Origin women, given that a large number are unauthorized migrants and the act of crossing over to the U.S. may be especially disruptive. As a result of data constraints, we were not able to distinguish between the short-term effects of family building and the possibility of disruption but we do find support for the possibility that the act of migration temporarily increases the fertility levels of Mexican-Origin women.

The elevated fertility of recent foreign-born Mexican-Origin women and the decreasing trend of current fertility with time in the U.S. did not occur to the same extent in the period 15 years earlier. In fact, recent immigrants are the only Mexican-Origin sub-group who have experienced an increase in their fertility differentials as compared to non-Hispanic Whites. Likely driving this increase across the two periods is the changing nature of the immigration stream between Mexico and the U.S. over the last decades. The earlier CPS data were collected coterminous to the implementation of the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), which was a legislative act that provided amnesty for many unauthorized immigrants already resident in the U.S. As a result of IRCA, women became more likely to migrate from Mexico and increasingly began to migrate after their husbands and fathers legalized (Donato 1992). Accordingly, they may be more likely to be at a point in their life course that is conducive to family building than would have been the case for women who migrated during the period prior to IRCA. Another possibility behind the increased fertility rates of recent immigrants in the current period as compared to the earlier period involves a selection effect. Migration increasingly may be selecting women with sociodemographic profiles that are conducive to higher fertility patterns, such as women with lower education levels and from more rural and/or marginalized areas that are characterized by higher fertility norms. The migration process between the U.S. and Mexico has matured and become less selective over time, specifically in particular communities with long histories of sustained migration to the U.S.

Despite a high risk of current fertility in the current period, recent immigrants do not display rates of cumulative fertility that are any higher than immigrants who have remained in the U.S. longer. In fact, the longer one resides in the U.S., the higher the differential in children ever born between them and non-Hispanic whites. The fact that we do not see the same trend in estimates of cumulative fertility rates as we did in current fertility suggests several possibilities. First, it is possible that, even in spite of high fertility activity close to the act of migration, recent immigrants are not yet able to make up for their delayed fertility as a result of migration. Supporting this explanation is the fact that the recent immigrants with lower rates of cumulative fertility are those who migrated during their peak childbearing years. Younger recent immigrants who migrated at the beginning for their childbearing years display higher rates of cumulative fertility than long-term immigrants. Bean and Stephen (1992) found similar results in their analysis of the 1970 and 1980 censuses, which revealed that every cohort of foreign-born women displayed evidence of increased fertility. They attributed these increases to disruption, but also demonstrated that the disruption effects were never entirely overcome in the measures of cumulative fertility. Another possibility behind the low rates of current fertility and high levels of cumulative fertility among immigrants with more time in the U.S. is that recent immigrants bear children at high rates soon after they arrive in the U.S. and as a result may be somewhat ahead of their fertility schedule. With more time in the U.S. they are able to lower their current fertility and still fulfill their cumulative fertility goals.

An exception to the trend of lower cumulative fertility among recent immigrants occurs in the oldest age group (40–44), whose estimates of completed fertility are slightly higher than the estimates of completed fertility of long-term immigrants. Women who are between the ages of 40–44 and who recently migrated are a unique group because they have spent nearly all of their childbearing years in Mexico at a time when Mexico was still characterized by high fertility norms. As a result, we would expect their cumulative fertility estimates to be high but do not necessarily expect this trend to continue in the future.

5.2 The Native-Born Mexican-Origin population

A similar discrepancy between patterns of current and cumulative fertility was observed among the two native-born populations. While third-generation women displayed lower current fertility risk than did second-generation women, they still displayed higher estimates of cumulative fertility than second-generation women. An explanation for this discrepancy is found in the comparison of estimates from the current period to those from fifteen years earlier. In the earlier period, third-generation women between the ages of 25–34 displayed higher current fertility rates than third-generation women of the same age in the current period. As a result, the oldest cohort of women in the current period (who were ages 25–29 in the earlier period), display high levels of completed fertility even though their levels of current fertility are lower. A cohort explanation suggests that the elevated completed fertility of third-generation is not likely to continue.

Even though the overall fertility of native-born women, and particularly third-generation Mexican-Origin women, appears to have declined over time, we also observed considerable increases in the fertility behavior of younger native-born women in both current and cumulative fertility. In the current period, at the younger ages, native-born women had fertility levels as high, and higher, than foreign-born women. A recent analysis of the 1995 NSFG found similar patterns among younger Mexican-Origin women (Carter 2000). As a result, the most pronounced differences in fertility rates between Mexican-Origin women in the U.S. and Mexican women in Mexico now occur among women who are younger than 24. These births are also increasingly non-marital. In the case of third-generation Mexican-Americans, their fertility pattern is remarkably similar to the one presented for African-American women, whereby they begin their reproductive lives with very high fertility rates at younger ages but then drop below the other sub-groups in the older age groups. These patterns question the utility of a strict cultural adaptation perspective and point to the possibility that the fertility rates of young native-born Mexican-Americans are due less to pronatalist values from Mexico and are more a product of the structural factors that are unique to the Mexican-American community in the U.S. This finding echoes the conclusion of a recent analysis of the high nuptiality rates characterizing the Mexican-Origin population in the U.S. (Raley, Durden and Wildsmith, forthcoming). Past explanations have relied on a cultural explanation, arguing that Mexican culture is highly familistic and places a high value on marriage. Yet an analysis of the National Survey of Family Growth (1995) found that early marriage among Mexican-Americans in the U.S. arises, not from Mexican familism, but rather from differences in family socioeconomic background and different timing of life course transitions, such as educational attainment, school enrollment and employment. The authors conclude that future attempts to relegate unaccounted for variation in demographic outcome variables to “cultural differences,” need to be tempered with more refined approaches that account for the economic and demographic realities facing race/ethnic minority groups in the U.S.

As noted by George Sanchéz in discussing the formation of Chicano identity in Los Angeles in the first part of the last century: "ethnicity, therefore, was not a fixed set of customs surviving from life in Mexico, but rather a collective identity that emerged from daily experience in the United States." As an alternative to the hypothesis that cultural values from Mexico shape the behavior of Mexican-Americans, we argue that the fertility behavior of the native-born Mexican-Origin population, and particularly the younger segments of the native-born population, should be framed within the U.S. social context. One such approach involves the racial stratification perspective, which identifies race/ethnic differentials in fertility as resulting from the different levels of racial stratification that characterize U.S. society (McDaniel 1996). In the case of Mexican-Americans, the social history of Mexicans in the U.S. and their precarious socioeconomic position have long been understudied in research on fertility and family formation (Forste and Tienda 1996). It is becoming increasingly clear that for many Latino groups, and especially for the Mexican-Origin population, a linear process of assimilation is not the predominant pattern characterizing their integration into U.S. society. According to Portes and Rumbaut (2001: 277): “Mexican immigrants represent the textbook example of theoretically anticipated effects of low immigrant human capital combined with a negative context of reception.” Compared to non-Hispanic whites, Mexican immigrant women and their native-born counterparts (who are wholly submerged in the U.S. social context), are characterized by more negative profiles, including low levels of high school completion, lower mean household incomes, lower rates of home ownership, and higher rates of unwed births (Bean and Tienda 1987; Portes and Rumbaut 2001).

The racial stratification perspective suggests that differential opportunity structures may pattern fertility behavior so that younger Mexican-American women, who face lower opportunity costs, engage in earlier fertility. Accordingly, any attempt to understand the sources of Mexican-American fertility differentials should account, not only for the group’s cultural heterogeneity, but also for its racial and ethnic inequality in broader U.S. society. The evidence presented here provides support for the possibility that the U.S. social context is becoming increasingly relevant in encouraging earlier and higher fertility behavior among the younger segments of the Mexican-American population at the same time that influences from Mexico are becoming less relevant. As such, fertility behavior represents a promising area with which to look at different processes of assimilation and acculturation that are occurring in ethnic immigrant communities in the U.S.

Footnotes

The term Mexican-Origin is used to describe the entire U.S. population that self-identifies with Mexican heritage, regardless of nativity status. The term Mexican-American denotes the native-born component of the Mexican-Origin population. In order to distinguish between the Mexican-Origin population in the U.S. and Mexico, we refer to the latter group as “Mexicans in Mexico.”

Several of the earlier surveys did not collect fertility information on women younger than 18. For those analyses only women ages 18–44 are included.

In 1989, Louisiana, New Hampshire and Oklahoma did not collect information on Hispanic Origin. By 1993 every state did. Denominators come from population estimates based on the 2000 census (see Hamilton et al. 2003).

Data were not available for women ages 18–19 in Mexico.

The youngest age group now includes women ages 15–19.

Marital status is measured at the time of the survey and not at the time of the birth. Accordingly, it is likely that the estimates presented here are an underestimation of the number of non-marital births, given that unwed mothers may wed following the birth

References

- Abma JC, Krivo LJ. “The Ethnic Context of Mexican-American Fertility”. Sociological Perspectives. 1991;34(2):145–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G. “Childbearing After Migration: Fertility Patterns of Foreign-born Women in Sweden”. International Migration Review. 2001;38(2):747–775. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, Frank D, Marta Tienda . The Hispanic population of the United States. Russell Sage Foundation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bean FD, Swicegood CG, Berg R. “Mexican-Origin Fertility: New Patterns and Interpretations”. Social Science Quarterly. 2000;81(1):404–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billari F, Francesco C, Kohler HP. “Patterns of Low and Lowest-Low Fertility in Europe”. Population Studies Volume. 2002;58(2):161–176. doi: 10.1080/0032472042000213695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter M. “Fertility of Mexican Immigrant Women in the U.S.: a closer look”. Social Science Quarterly. 2000;81(4):1073–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Nacional de Población (CONAPO) “La Revolución Silenciosa: descenso de la fecundidad en México, 1974–1999”. Mexico City: Mexico; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Day JC. Population Projection of the United States by Age, Sex, Race and Hispanic Origin: 1995 to 2050. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan B, Trejo S. “Ethnic Choices and the Intergenerational Progress of Mexican-Americans”. University of Texas-at Austin: Population Research Center Working Paper Series 04-5-02; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Durand J, Massey D, Zenteno R. “Mexican Immigration to the United States: Continuities and Changes”. Latin American Research Review. 2001;35(3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K. “Duration of Residence in the United States and the Fertility of U.S. Immigrants”. International Migration Review. 1990;24(1):34–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forste R, Tienda M. “What’s Behind Racial and Ethnic Fertility Differentials?”. Population and Development Review. 1996;22:109–133. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ. National Vital Statistics Reports. 12. Vol 51. Hyattsville, Maryland: The National Center for Health Statistics; 2003. “Revised Birth and Fertility Rates for the 1990s and New Rates for Hispanic Populations, 2000 and 2001: United States”. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Sean-Shong, Saenz R. “Fertility of Chinese Immigrants in the U.S.: Testing a Fertility Emancipation Hypothesis”. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997;59:50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografia e Informática. (INEGI) ENADID. Encuesta Nacional de la Dinámica Demográfica. Aguascalientes, México: Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson SH, Rendall MS. “The Fertility Contribution of Mexican Immigration to the United States”. Demography. 2004;41(1):129–150. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen SR, Adams RP. “Predicting Mexican-American Family Planning Intentions: An Application and Test of a Social Psychological Model”. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1988;50:107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Menack F, Park MN. National Vital Statistics Reports. vol. 50. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. “Births: Final Data for 2000”. no. 5. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel A. “Fertility and Racial Stratification”. Population and Development Review. 1996;22:134–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ng E, Nault R. “Fertility among Recent Immigrant Women to Canada, 1991: An Examination of the Disruption Hypothesis”. International Migration. 1997;35(4):559–580. doi: 10.1111/1468-2435.00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes, Alejandro, Rubén, Rumbaut G. Legacies : the story of the immigrant second generation. University of California Press; Russell Sage Foundation: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Raley K, Durden E, Forthcoming EWildsmith. Social Science Quarterly. “Understanding Mexican-American Marriage Patterns Using a Life-Course Approach”. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss, Ronald R, James A, Sweet . Postwar fertility trends and differentials in the United States. Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez G. Becoming Mexican-American: Ethnicity, Culture and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900–1945. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen EH. At the Crossroads: Fertility of Mexican-American Women. New York: Garland Publishing Inc; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Waldorf B. “Impacts of Immigrant Fertility on Population Size and Composition”. In: Pandit K, Withers SD, editors. Migration and Restructuring in the U.S.: a geographic perspective. Landam, MD: Rowman and Littlefield; 1999. pp. 193–221. [Google Scholar]