Abstract

Background

Gangliogliomas are low-grade glioneuronal tumors of the central nervous system and the commonest cause of chronic intractable epilepsy. Most gangliogliomas (>70%) arise in the temporal lobe, and infratentorial tumors account for less than 10%. Posterior fossa gangliogliomas can have the features of a classic supratentorial tumor or a pilocytic astrocytoma with focal gangliocytic differentiation, and this observation led to the hypothesis tested in this study - gangliogliomas of the posterior fossa and spinal cord consist of two morphologic types that can be distinguished by specific genetic alterations.

Results

Histological review of 27 pediatric gangliogliomas from the posterior fossa and spinal cord indicated that they could be readily placed into two groups: classic gangliogliomas (group I; n = 16) and tumors that appeared largely as a pilocytic astrocytoma, but with foci of gangliocytic differentiation (group II; n = 11). Detailed radiological review, which was blind to morphologic assignment, identified a triad of features, hemorrhage, midline location, and the presence of cysts or necrosis, that distinguished the two morphological groups with a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 100%. Molecular genetic analysis revealed BRAF duplication and a KIAA1549-BRAF fusion gene in 82% of group II tumors, but in none of the group I tumors, and a BRAF:p.V600E mutation in 43% of group I tumors, but in none of the group II tumors.

Conclusions

Our study provides support for a classification that would divide infratentorial gangliogliomas into two categories, (classic) gangliogliomas and pilocytic astrocytomas with gangliocytic differentiation, which have distinct morphological, radiological, and molecular characteristics.

Keywords: Ganglioglioma, Pilocytic astrocytoma, Glioneuronal, BRAF, Mutation

Background

Gangliogliomas are rare mixed glioneuronal tumors, composed of neoplastic glial and neuronal cells and representing 0.5-1.7% of all neuroepithelial tumors in the central nervous system (CNS) [1-4]. However, they constitute up to 4% of CNS tumors in the pediatric population and are the commonest tumor associated with chronic intractable focal epilepsy. Gangliogliomas are found throughout the CNS, but most (>70%) are localized to the temporal lobe, while they are uncommon in the posterior fossa (~5%) and spinal cord (~3%) [2,5-9]. Gangliogliomas in the cerebral lobes are often circumscribed tumors and amenable to complete surgical resection, which is reflected in good survival data [10]. Gangliogliomas in the posterior fossa or spinal cord have a poorer outcome, but it is unclear whether anatomic location or an inherent variance in biologic behavior accounts for this difference [1,6,10].

Genetic alterations in elements of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway have been identified in many low-grade neuroepithelial tumors, including pilocytic astrocytoma (PA), pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (PXA), and ganglioglioma [11-14]. Recent studies have demonstrated that specific mutations are enriched in certain tumors; for example, KIAA1549-BRAF fusions are found in PAs, and BRAF:p.V600E mutations are frequently detected in PXAs (~70%) [14-19]. BRAF:p.V600E mutations are also present in about one quarter of gangliogliomas [14].

Through the neuropathology referral practice at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, we occasionally review the pathology of infratentorial gangliogliomas that demonstrate the features of a classic pilocytic astrocytoma, except for one or two collections of dysmorphic ganglion cells that are clearly part of the neoplastic process. This observation led to the hypothesis tested in this study; gangliogliomas of the posterior fossa and spinal cord consist of two morphologic types that can be distinguished by their molecular genetic alterations.

Methods

The study cohort consisted of 27 WHO grade I gangliogliomas arising in the posterior fossa or spinal cord. Clinical and radiological features were compiled (Table 1). Median age at diagnosis was 10 years (range: 0.6 - 21 years), and the female:male ratio was 14:13. No patient fulfilled clinical criteria for the diagnosis of NF-1. Review of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was undertaken by one radiologist, who was blinded to pathology review and morphologic group assignment. Tumors were evaluated radiologically on the following parameters: location (dominant and secondary sites of involvement), relationship to midline, circumscription, extent of edema and restricted diffusion, and the presence of cysts or necrosis, hemorrhage, and enhancement. The study was conducted with St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Institutional Review Board approval (XPD07-107).

Table 1.

Clinical and radiological data for two morphological groups of ganglioglioma

| |

Pathology group |

Age @ diagNosis (years) |

Gender |

Dominant site of tumor |

BRAF: p.V600E |

BRAF duplication |

KIAA1549-BRAF fusion gene

|

Neuroimaging |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midline location | Circumscribed | Cysts/necrosis | Hemorrhage | Enhancement | Edema | Restricted diffusion | ||||||||

| GG01 |

I |

6 |

M |

Cerebellar hemisphere |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

0 |

0 |

+ |

+ |

No |

| GG02 |

I |

9 |

F |

Cerebellum |

Yes |

No |

No |

n/a |

||||||

| GG03 |

I |

21 |

F |

Cerebellar hemisphere |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

0 |

0 |

++ |

+++ |

Yes |

| GG04 |

I |

9 |

F |

Medulla |

Yes |

No |

n/a |

No |

No |

0 |

0 |

+++ |

0 |

No |

| GG05 |

I |

8 |

F |

Medulla |

Yes |

No |

n/a |

No |

Yes |

0 |

0 |

++ |

0 |

n/a |

| GG06 |

I |

8 |

M |

Medulla |

Yes |

No |

n/a |

No |

No |

0 |

0 |

+++ |

+ |

Yes |

| GG07 |

I |

15 |

F |

MCP |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

0 |

0 |

+++ |

++ |

No |

| GG08 |

I |

8 |

F |

Cerebellar hemisphere |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

+++ |

0 |

+ |

0 |

No |

| GG09 |

I |

11 |

F |

MCP |

No |

No |

n/a |

No |

Yes |

0 |

0 |

++++ |

0 |

n/a |

| GG10 |

I |

11 |

F |

Medulla |

No |

No |

n/a |

No |

No |

0 |

0 |

++ |

++ |

n/a |

| GG11 |

I |

12 |

M |

Medulla |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

0 |

0 |

+++ |

++ |

Yes |

| GG12 |

I |

1.8 |

M |

Pons |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

0 |

0 |

+ |

++ |

No |

| GG13 |

I |

21 |

M |

MCP |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

+ |

0 |

+++ |

+ |

n/a |

| GG14 |

I |

0.6 |

M |

MCP |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

0 |

0 |

+ |

+ |

No |

| GG15 |

I |

15 |

F |

Cervico-medullary |

No |

No |

No |

n/a |

||||||

| GG16 |

I |

14 |

M |

Medulla |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

0 |

0 |

++++ |

++ |

No |

| GG17 |

II |

12 |

M |

Vermis |

No |

Yes |

Yes - ex16:ex9 |

No |

Yes |

++ |

0 |

+ |

0 |

Yes |

| GG18 |

II |

4 |

F |

Vermis |

No |

Yes |

Yes - ex15:ex9 |

Yes |

Yes |

+ |

+ |

+++ |

+ |

Yes |

| GG19 |

II |

12 |

F |

Cord (thoraco-lumbar) |

No |

Yes |

Yes - ex15:ex9 |

Yes |

No |

+ |

+ |

++ |

0 |

n/a |

| GG20 |

II |

16 |

F |

Cord (cervico-thoracic) |

No |

Yes |

Yes - ex15:ex9 |

Yes |

Yes |

+++ |

0 |

++ |

+++ |

n/a |

| GG21 |

II |

18 |

M |

Cord (cervico-thoracic) |

No |

Yes |

Yes - ex15:ex9 |

Yes |

No |

+++ |

+ |

+ |

++++ |

n/a |

| GG22 |

II |

9 |

F |

Vermis |

No |

Yes |

Yes - ex15:ex9 |

No |

Yes |

++ |

0 |

+++ |

++ |

No |

| GG23 |

II |

17 |

F |

Vermis |

No |

Yes |

Yes - ex16:ex9 |

No |

Yes |

++ |

+ |

+ |

++ |

Yes |

| GG24 |

II |

10 |

M |

Cord (cervical) |

No |

Yes |

Yes - ex16:ex11 |

Yes |

Yes |

+++ |

+ |

++ |

++ |

n/a |

| GG25 |

II |

9 |

M |

Vermis |

No |

Yes |

Yes - ex16:ex11 |

Yes |

No |

++++ |

0 |

++++ |

+ |

Yes |

| GG26 |

II |

4 |

M |

Medulla |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

0 |

0 |

+++ |

++ |

Yes |

| GG27 | II | 9 | M | Midbrain | No | No | No | No | Yes | +++ | 0 | + | ++ | n/a |

M = male; F = female.

MCP = middle cerebellar peduncle.

n/a = Not available.

0 - ++++; magnitude scale.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Standard histological preparations, 4 μm formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections stained with hematoxylin & eosin were supplemented with immunohistochemical preparations. Antibodies to the following proteins were utilized for routine pathologic evaluation: glial fibrillary acidic protein (1:400, Dako M076101), synaptophysin (1:400, Leica MCL-L-SYNAP-299), NEU-N (1:5000, Chemicon MAB377), neurofilament protein (1:100, Dako M076229), microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2 1:10,000, Sigma M4403), and Ki67 (1:200, Dako M7240).

Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (iFISH)

Dual-color iFISH was performed on 4 μm FFPE tissue sections. Probes were derived from BAC clones (BACPAC Resources, Oakland, CA), labeled with an AlexaFluor-488 or AlexaFluor-555 fluorochrome, and validated on normal control metaphase spreads to confirm chromosomal location. BAC clones RP11-96I22 and RP11-837G3 were used to screen for BRAF duplication at 7q34 (control probe on 7p11, RP11-251I15 and RP11-746C13). RP11-837G3 and RP11-948O19 were used in a ‘break-apart’ probe strategy to screen for BRAF rearrangement. RP11-265 F21 and RP11-297 N18 (ETV6), along with RP11-96B23 and RP11-948I15 (NTRK3), were used to screen for ETV6-NTRK3 fusions.

Nucleic acid extraction and mutation analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from 10 μm FFPE scrolls, using the Maxwell® 16 Plus LEV DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison WI), and total RNA was extracted from FFPE scrolls using the Maxwell® 16 RNA FFPE prototype extraction kit (Promega, Madison WI), according to manufacturer’s instructions. BRAF:p.V600, KRAS:p.G12, and KRAS:p.Q61 were sequenced in genomic DNA using previously published primers [12]. PCRs were performed using GoTaq® Long PCR Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI). All PCR products were visualized using 1% agarose gels. Direct sequencing of PCR products was performed using BigDye version 3.1 and a 3730XL DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Results were screened using CLC Main Workbench sequence analysis software version 6.0.2 (CLC bio, Cambridge, MA).

Real-time quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) for KIAA1549-BRAF detection

First-strand cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg total RNA in a 20 μL reaction mixture using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The mixture was incubated at 25°C for 5 min, 42°C for 30 min, and 85°C for 5 min. qRT-PCR was performed using TaqMan reagents and the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Forward and reverse primers and TaqMan probes are listed in Table 2. KIAA1549-BRAF probes were labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM) as a 5’ reporter dye and 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) as the 3′ quencher dye. A 10 μL aliquot of cDNA (corresponding to 100 ng of total RNA) was added to the PCR reaction mix to reach a final volume of 50 μL containing 25 μL of TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix (2X) (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), 300 nM of each forward and reverse primer, and 50 nM of TaqMan probe. Human GAPDH (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) was used as an internal control. The thermal cycling conditions were 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C for denaturation, and 50 cycles at 95°C for 15 s followed by 60°C for 60s for annealing and extension. Presence of the fusion product was indicated by the appearance of signal above the critical threshold (Ct). All experiments were performed in duplicate.

Table 2.

Primers and TaqMan probes for KIAA1549-BRAF fusion gene variants

| Gene fusion | Primer | TaqMan probe |

|---|---|---|

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 13 - BRAF exon 11) forward |

GGGTCCCCAGTAAGATCCAG |

ATCGCCATGCAGCCGATCCCGGCACCT |

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 13 - BRAF exon 11) reverse |

CTCGAGTCCCGTCTACCAAG |

|

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 15 - BRAF exon 9) forward |

CGTCCACAACTCAGCCTACATC |

ACCACAGGTTTGTCTGC |

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 15 - BRAF exon 9) reverse |

CCTGGAGATTTCTGTAAGGCTTTC |

|

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 15 - BRAF exon 11) forward |

AGCGATGGCACCTACAGGA |

CGTCCACAACTCAGCCTACATCGGATGCCCA |

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 15 - BRAF exon 11) reverse |

TCATCACTCGAGTCCCGTCT |

|

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 16 - BRAF exon 9) forward |

CCAGACGGCCAACAATCC |

ACCACAGGTTTGTCTGC |

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 16 - BRAF exon 9) reverse |

CCTGGAGATTTCTGTAAGGCTTTC |

|

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 16 - BRAF exon 10) forward |

CAGTGGGGGTCCTTCTACAG |

AGCCCAGACGGCCAACAATCCCTGCAG |

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 16 - BRAF exon 10) reverse |

CTTCCTTTCTCGCTGAGGTC |

|

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 16 - BRAF exon 11) forward |

AGTGGGGGTCCTTCTACAGC |

AGCCCAGACGGCCAACAATCCCTGCAG |

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 16 - BRAF exon 11) reverse |

CATGCCACTTTCCCTTGTAG |

|

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 17 - BRAF exon 10) forward |

GAATGACTCCCCCGACG |

ACCACAGGTTTGTCTGCTACCCCCCCTGC |

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 17 - BRAF exon 10) reverse |

AGGCTTTCACGTTAGTTAGTGAGC |

|

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 18 - BRAF exon 10) forward |

TGCTGCCAGAGGGATCTACTC |

ACCACAGGTTTGTCTGC |

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 18 - BRAF exon 10) reverse |

CCTGGAGATTTCTGTAAGGCTTTC |

|

|

KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 19 - BRAF exon 9) forward |

CCAGGCTGGCCTTCGTAC |

ACCACAGGTTTGTCTGC |

| KIAA1549-BRAF (KIAA exon 19 - BRAF exon 9) reverse | CCTGGAGATTTCTGTAAGGCTTTC |

Results

Histopathological features

Evaluation of histopathology and group assignment took place before the results of molecular analyses were established. Even though all tumors (n = 27) contained a low-grade glial element and a population of dysmorphic ganglion cells and thus qualified for a diagnosis of ganglioglioma, they could be readily assigned to two groups on the basis of their histopathological features.

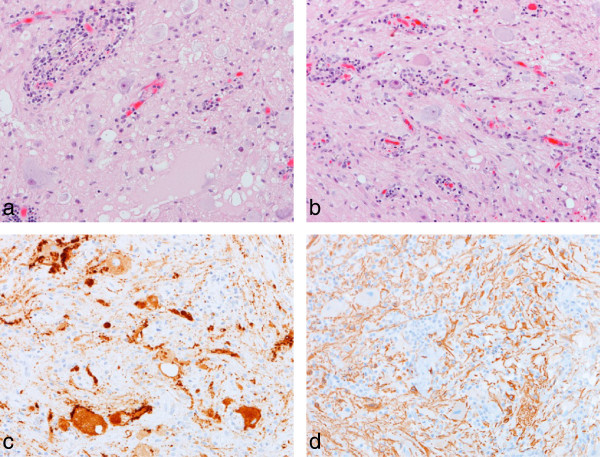

Group I - classic ganglioglioma

Tumors belonging to group I (16/27; 59%) contained dysmorphic ganglion cells and atypical glial cells, which were admixed throughout most of the tumor (Figure 1). Many group I tumors (13/16; 81%) exhibited aggregates of perivascular lymphocytes. Eosinophilic granular bodies were present in 7 of 16 tumors, but Rosenthal fibers were present in only three tumors. The supporting matrix varied from a reticulin-rich fibrous network, occasionally forming a lobular configuration, to a fine fibrillary component with variable cystic degeneration. The pleomorphism shown by neoplastic ganglion cells in group I tumors appeared greater than that of ganglion cells in group II tumors. Multinucleation in ganglion cells was a feature of several tumors in this group. The glial element in group I tumors was varied; it showed a fibrillary phenotype in most cases (10/16), but an admixed fibrillary and pilocytic phenotype in remaining cases. The fibrillary component diffusely infiltrated adjacent parenchyma in several tumors. Anaplastic features, including significant mitotic activity, were not detected, and there was no necrosis.

Figure 1.

Group 1 tumors – classic ganglioglioma. The classic pathologic features of a ganglioglioma are demonstrated (a, b), including perivascular aggregates of lymphoid cells, dysmorphic ganglion cells, and a fibrillary glial cell component. Immunoreactivity for synaptophysin highlights ganglion cells and their abnormal neuritic processes (c), while the glial component is GFAP-positive (d). All images, x200.

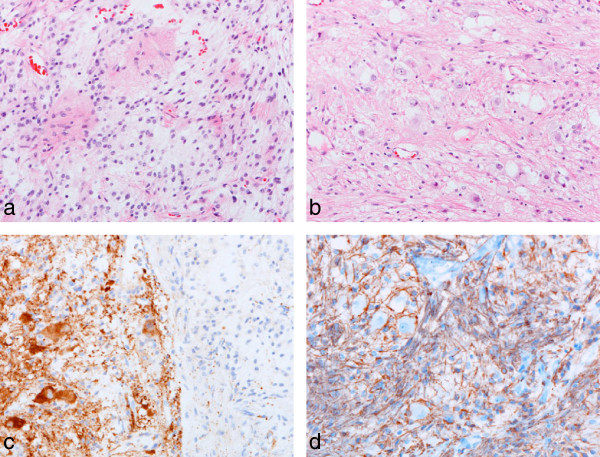

Group II - pilocytic astrocytoma with focal gangliocytic differentiation

Tumors in group II (n = 11/27; 41%) were largely characterized by the features of a classic pilocytic astrocytoma, but all had foci of gangliocytic differentiation (Figure 2). All tumors displayed a glial element with a biphasic architecture, which alternated between solid areas composed of piloid cells and cystic regions showing variable myxoid degeneration and containing disaggregated cells with a piloid or astrocytic phenotype. Four tumors contained a few areas where neoplastic glial cells showed an oligodendroglial phenotype. Variable numbers of Rosenthal fibers were found in the majority of tumors. Gangliocytic differentiation manifested as distinct clusters of haphazardly arranged dysmorphic ganglion cells in just one or two regions of the tumor. These cells were atypical and clearly part of the neoplastic process, occurring in areas that did not incorporate adjacent parenchyma. Bi-nucleation was a feature of ganglion cells in two tumors. Microvascular proliferation of the type seen in pilocytic astrocytomas was detected in several tumors, and two contained small foci of necrosis. The was no rosette formation.

Figure 2.

Group II tumors - pilocytic astrocytoma with focal gangliocytic differentiation. The classic pathologic features of a posterior fossa pilocytic astrocytoma (a) combines focally with collections of dysmorphic ganglion cells (b). The edge of a gangliocytic nodule is highlighted by immunoreactivity for synaptophysin (c). An admixed GFAP-positive pilocytic and fibrillary astrocytic component surrounds a few dysmorphic ganglion cells (d). All images, x200.

Immunohistochemistry gave the expected results across both groups of tumors. Many neoplastic glial cells were GFAP-positive, while ganglion cells showed immunoreactivities for MAP2, synaptophysin and neurofilament proteins (Figures 1 and 2). NEU-N was expressed weakly by a few ganglion cells in group I tumors, and to a variable extent in ganglion cells in group II tumors. Ki67 immunolabeling was low in all tumors.

Molecular features

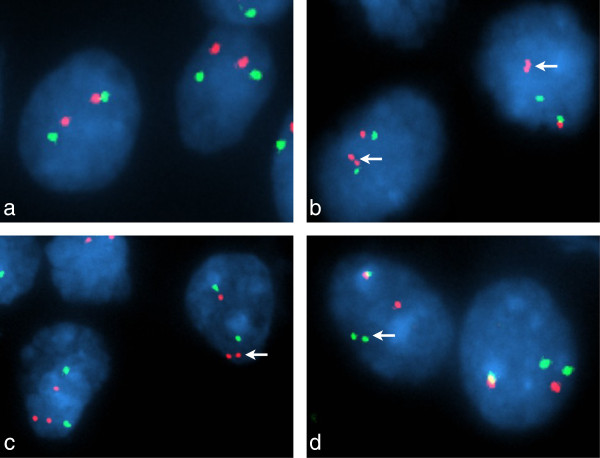

iFISH demonstrated BRAF duplication in 9 of 11 (82%) group II tumors (Figure 3), but in none of the group I tumors (Table 1). One group II tumor, GG17, demonstrated BRAF duplication and a potential BRAF fusion, the latter on the basis of a ‘break-apart’ probe profile that showed one (normal) overlapping pair of signals and one ‘split’ pair of signals (Figure 3d). KIAA1549-BRAF fusions were found in all 9 group II tumors with BRAF duplication, but in no other group I or group II tumor. Three KIAA1549-BRAF fusion variants were identified; exon16:exon9, exon15:exon9, and exon16:exon11 (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of the BRAF locus. FISH probe profiles (a, b, c, BRAF – red; 7p control – green; d, centromeric BRAF – green; telomeric BRAF – red) indicate normal BRAF in GG02 (a) and a classic ‘doublet’ pattern with these probes for duplicated BRAF in GG21 (b, arrows). In GG17 (c, d), FISH preparations indicated a complex alteration; probe profiles showed both duplication of BRAF and a monallelic separation of duplicated BRAF.

BRAF:p.V600E mutations were detected in 7 of 16 (43%) group I tumors, but in no group II tumor. No mutations at KRAS:p.G12 or KRAS:p.Q61 were identified across the tumor cohort. No tumors showed evidence of an ETV6-NTRK3 fusion.

Radiological features

Of 27 patients in the study cohort, MRI with and without contrast and diffusion-weighted imaging at presentation were available for review in 25 and 16, respectively. Of imaged group I tumors, 3/14 were well-circumscribed, compared to 7/11 in group II (Table 1). Among group I tumors, the most common primary site of tumor involvement was the medulla, followed by the middle cerebellar peduncle (MCP), with secondary involvement of the pons (8/14), MCP (5/14), cervical spinal cord (4/14), cerebellar hemisphere (3/14) and vermis (1/14). Among group II tumors, the vermis and spinal cord were the most frequent sites of primary involvement. One group II tumor was centered in the medulla with secondary involvement of the MCP, pons and cervical cord, and another was centered on the midbrain with secondary thalamic involvement. Three of five vermian tumors had secondary involvement of the cerebellar hemispheres. All imaged tumors enhanced, but group II tumors were more frequently cystic or necrotic and hemorrhagic; no group I tumor demonstrated hemorrhage on MRI. A triad of radiological features, encompassing hemorrhage, midline location, and the presence of cysts or necrosis, was able to separate group I and group II tumors with a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 100%.

Discussion

Gangliogliomas are rare low-grade neuroepithelial tumors of the CNS consisting of admixed mature glial and neuronal elements [2,4]. Most arise in the temporal lobe or other supratentorial sites, but they occasionally occur in the posterior fossa or spinal cord [2,5,6,20]. Most classic gangliogliomas contain an idiosyncratic glial component that combines pilocytic and fibrillary phenotypes, and in a significant proportion of tumors this element infiltrates surrounding parenchyma blurring the border between tumor and normal tissue.

On the basis of our clinical experience with a few infratentorial low-grade glioneuronal tumors that were largely pilocytic astrocytomas but exhibited foci of gangliocytic differentiation, this study tested the hypothesis that gangliogliomas of the posterior fossa and spinal cord can be divided into distinct morphological groups and that these groups would also be characterized by distinct molecular alterations. In a series of 27 gangliogliomas, we found that 16 (59%) had the features of a classic ganglioglioma with admixed neuronal and glial elements, while 11 (41%) would have been classified as pilocytic astrocytomas, were it not for the presence of a few circumscribed collections of cells with gangliocytic differentiation. Our detailed review of patients’ neuroimaging indicated that the two groups of tumors could also be differentiated by specific radiological characteristics; a triad of features was able to separate the two morphologic groups with 91% sensitivity and 100% specificity. The detailed pathology of a large series of infratentorial gangliogliomas has not been previously reported, but one study noted that a cerebellar ganglioglioma demonstrated a prominent pilocytic component [11].

Recent genomic studies have defined the genetic alterations of most low-grade neuroepithelial tumors. Alterations in genes involved in the MAPK pathway dominate; KIAA1549-BRAF fusions characterize PAs, occurring in approximately 90% of posterior fossa tumors but at lower frequencies in spinal cord and supratentorial tumors [12,17-19]. Some PAs demonstrate an alternative BRAF rearrangement, where BRAF partners with another gene, including FAM131B, MACF1, FXR1, RNF130, CLCN6, MKRN1 and GNAI1[17,19,21]. BRAF:p.V600E mutations occur in PXAs (~70%), gangliogliomas (~25%), and WHO grade II diffuse astrocytomas (~20%) [11,14,19,22,23]. Rarely, mutations of KRAS are found in a PA or grade II diffuse glioma [12,19,24], and an ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene has been reported in a PXA [19]. However, such genetic abnormalities were not harbored by those gangliogliomas in which we were unable to show a KIAA1549-BRAF fusion or BRAF:p.V600E mutation. Low-grade neuroepithelial tumors presenting in childhood rarely contain an IDH1:p.R132H mutation. This mutation is regarded as a hallmark of adult-type disease, but can occur in adolescents with a WHO grade II diffuse glioma [19]. Another rare glioneuronal tumor of the posterior fossa, the rosette-forming glioneuronal tumor of the fourth ventricle, has a distinct morphology from the two types of ganglioglioma in our study [25,26]. Additionally, it is not characterized by KIAA1549-BRAF fusion or BRAF:p.V600E mutation [27].

Our analysis of molecular alterations in infratentorial gangliogliomas has revealed a clear distinction between two morphological groups. Seven of sixteen (44%) tumors in group I, with features of a classic ganglioglioma, harbored a BRAF:p.V600E mutation. This mutation is the most common genetic alteration yet found in gangliogliomas and links this infratentorial morphologic group to typical cerebral gangliogliomas. Group II contained tumors that were largely pilocytic astrocytomas, but with foci of gangliocytic differentiation; 82% of these tumors were characterized by a KIAA1549-BRAF fusion gene, which is the hallmark of pilocytic astrocytomas. Therefore, the frequency of KIAA1549-BRAF fusions in infratentorial PAs and gangliogliomas appears very similar.

Conclusions

We have provided clear evidence of the separation of posterior fossa and spinal gangliogliomas into two groups distinguished by their morphological, radiological and genetic characteristics. One group should be regarded as classic gangliogliomas, while on the basis of molecular data the other might be better classified as pilocytic astrocytomas with gangliocytic differentiation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Pathology review: KG, TR, DWE. Molecular analysis: KG, WO, JDD, CP, RC-U. Clinical data collection: IQ, RGT. Radiology review: JHH. Manuscript writing: KG, RGT, DWE. Study conception and oversight: DWE. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Kirti Gupta, Email: kirtigupta10@yahoo.co.in.

Wilda Orisme, Email: wilda.orisme@stjude.org.

Julie H Harreld, Email: julie.harreld@stjude.org.

Ibrahim Qaddoumi, Email: ibrahim.qaddoumi@stjude.org.

James D Dalton, Email: james.dalton@stjude.org.

Chandanamali Punchihewa, Email: Chandanamali.Punchihewa@STJUDE.ORG.

Racquel Collins-Underwood, Email: Racquel.Collins-Underwood@STJUDE.ORG.

Thomas Robertson, Email: Thomas_Robertson@health.qld.gov.au.

Ruth G Tatevossian, Email: ruth.tatevossian@stjude.org.

David W Ellison, Email: David.Ellison@stjude.org.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC) and by the Indo-US Science and Technology Forum (KG). The support of Charlene Henry and the staff of Anatomic Pathology at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Ying Yuan of Biostatistics for advice on the analysis of radiologic data.

References

- Becker AJ, Wiestler OD, Figarella-Branger D. In: Ganglioglioma and Gangliocytoma. 4. Bosman FT, editor. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2007. WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system. [Google Scholar]

- Blumcke I, Wiestler OD. Gangliogliomas: an intriguing tumor entity associated with focal epilepsies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;2(7):575–584. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.7.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyan-Raman UP, Olivero WC. Ganglioglioma: a correlative clinicopathological and radiological study of ten surgically treated cases with follow-up. Neurosurgery. 1987;2(3):428–433. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyken C. et al. Supratentorial gangliogliomas: histopathologic grading and tumor recurrence in 184 patients with a median follow-up of 8 years. Cancer. 2004;2(1):146–155. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baussard B. et al. Pediatric infratentorial gangliogliomas: a retrospective series. J Neurosurg. 2007;2(4 Suppl):286–291. doi: 10.3171/PED-07/10/286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jallo GI, Freed D, Epstein FJ. Spinal cord gangliogliomas: a review of 56 patients. J Neurooncol. 2004;2(1):71–77. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000024747.66993.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagares A. et al. Ganglioglioma of the brainstem: report of three cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2001;2(5):315–322. doi: 10.1016/S0090-3019(01)00618-8. discussion 322–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safavi-Abbasi S. et al. Posterior cranial fossa gangliogliomas. Skull Base. 2007;2(4):253–264. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-984486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwood DA, MacFarlane MR. Pontomedullary ganglioglioma: a rare tumour in an unusual location. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;2(1):108–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang FF. et al. Central nervous system gangliogliomas. Part 2: clinical outcome. J Neurosurg. 1993;2(6):867–873. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.79.6.0867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty MJ. et al. Activating mutations in BRAF characterize a spectrum of pediatric low-grade gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2010;2(7):621–630. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forshew T. et al. Activation of the ERK/MAPK pathway: a signature genetic defect in posterior fossa pilocytic astrocytomas. J Pathol. 2009;2(2):172–181. doi: 10.1002/path.2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister S. et al. BRAF gene duplication constitutes a mechanism of MAPK pathway activation in low-grade astrocytomas. J Clin Invest. 2008;2(5):1739–1749. doi: 10.1172/JCI33656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler G. et al. Analysis of BRAF V600E mutation in 1,320 nervous system tumors reveals high mutation frequencies in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, ganglioglioma and extra-cerebellar pilocytic astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;2(3):397–405. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0802-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeuken JW, Wesseling P. MAPK pathway activation through BRAF gene fusion in pilocytic astrocytomas; a novel oncogenic fusion gene with diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic potential. J Pathol. 2010;2(4):324–328. doi: 10.1002/path.2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DT. et al. MAPK pathway activation in pilocytic astrocytoma. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;2(11):1799–1811. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0898-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DT. et al. Recurrent somatic alterations of FGFR1 and NTRK2 in pilocytic astrocytoma. Nat Genet. 2013;2(8):927–932. doi: 10.1038/ng.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatevossian RG. et al. MAPK pathway activation and the origins of pediatric low-grade astrocytomas. J Cell Physiol. 2010;2(3):509–514. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies genetic alterations in pediatric low-grade gliomas. Nat Genet. 2013;2(6):602–612. doi: 10.1038/ng.2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. et al. Brainstem gangliogliomas: a retrospective series. J Neurosurg. 2013;2(4):884–888. doi: 10.3171/2013.1.JNS121323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cin H. et al. Oncogenic FAM131B-BRAF fusion resulting from 7q34 deletion comprises an alternative mechanism of MAPK pathway activation in pilocytic astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;2(6):763–774. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0817-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya S. et al. BRAF(V600E) mutation is a negative prognosticator in pediatric ganglioglioma. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;2(6):901–910. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1120-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias-Santagata D. et al. BRAF V600E mutations are common in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. PLoS One. 2011;2(3):e17948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janzarik WG. et al. Further evidence for a somatic KRAS mutation in a pilocytic astrocytoma. Neuropediatrics. 2007;2(2):61–63. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-984451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T, Scheithauer BW, Hirose T. A rosette-forming glioneuronal tumor of the fourth ventricle: infratentorial form of dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor? Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;2(5):582–591. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200205000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preusser M. et al. Rosette-forming glioneuronal tumor of the fourth ventricle. Acta Neuropathol. 2003;2(5):506–508. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0758-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessi M. et al. Absence of KIAA1549-BRAF fusion in rosette-forming glioneuronal tumors of the fourth ventricle (RGNT) J Neurooncol. 2012;2(1):21–25. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0940-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]