Abstract

Background

Breast cancer is a major health problem that threatens the lives of millions of women worldwide each year. Most of the chemotherapeutic agents that are currently used to treat this complex disease are highly toxic with long-term side effects. Therefore, novel generation of anti-cancer drugs with higher efficiency and specificity are urgently needed.

Methods

Breast cancer cell lines were treated with eugenol and cytotoxicity was measured using the WST-1 reagent, while propidium iodide/annexinV associated with flow cytometry was utilized in order to determine the induced cell death pathway. The effect of eugenol on apoptotic and pro-carcinogenic proteins, both in vitro and in tumor xenografts was assessed by immunoblotting. While RT-PCR was used to determine eugenol effect on the E2F1 and survivin mRNA levels. In addition, we tested the effect of eugenol on cell proliferation using the real-time cell electronic sensing system.

Results

Eugenol at low dose (2 μM) has specific toxicity against different breast cancer cells. This killing effect was mediated mainly through inducing the internal apoptotic pathway and strong down-regulation of E2F1 and its downstream antiapoptosis target survivin, independently of the status of p53 and ERα. Eugenol inhibited also several other breast cancer related oncogenes, such as NF-κB and cyclin D1. Moreover, eugenol up-regulated the versatile cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1 protein, and inhibited the proliferation of breast cancer cells in a p53-independent manner. Importantly, these anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects were also observed in vivo in xenografted human breast tumors.

Conclusion

Eugenol exhibits anti-breast cancer properties both in vitro and in vivo, indicating that it could be used to consolidate the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer through targeting the E2F1/survivin pathway, especially for the less responsive triple-negative subtype of the disease.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Breast cancer, Eugenol, E2F1, Survivin

Background

Breast cancer remains a worldwide public health concern and a major cause of morbidity and mortality among females [1]. Treatment of breast cancer includes, tumor resection, radiation, endocrine therapy, cytotoxic chemotherapy and antibody-based therapy [2]. However, resistance to these forms of therapies and tumor recurrence are very frequent. Furthermore, there is relative lack of effective therapies for advanced-stage and some forms of the disease such as triple negative breast cancer (TNBC). Recently, PARP inhibitors showed promising results against tumors with mutated BRCA1 and TNBC [3,4]. Therefore, scientists keep seeking for new agents with higher efficiency and less side effects. Of 121 prescription drugs in use for cancer treatment, 90 are derived from plant species and 74% of these drugs were discovered by investigating a folklore claim [5,6]. Indeed, several natural products and dietary constitutes exhibit anti-cancer properties without considerable adverse effects [7,8]. Therefore, the abundance of flavonoids and related polyphenols in the plant kingdom makes it possible that several hitherto uncharacterized agents with chemopreventive or chemotherapeutic effects are still to be identified. Several of these products such as curcumin, green tea, soy and red clover are currently in clinical trials for the treatment of various forms of cancer [9].

Eugenol (4-allyl (-2-mthoxyphenol)), a phenolic natural compound available in honey and in the essential oils of different spices such as Syzgium aromaticum (clove), Pimenta racemosa (bay leaves), and Cinnamomum verum (cinnamon leaf), has been exploited for various medicinal applications. It serves as a weak anaesthetic and has been used by dentists as a pain reliever and cavity filling cement (“clove oil”). In Asian countries, eugenol has been used as antiseptic, analgesic and antibacterial agent [10]. In addition, eugenol has antiviral [11], antioxidant [12] and anti-inflamatory functions. Furthermore, while it has been proved not to be carcinogenic neither mutagenic [13], eugenol has several anti-cancer properties. Indeed, eugenol has antiproliferative effects in diverse cancer cell lines as well as in B16 melanoma xenograft model [14-16]. Eugenol induced apoptosis in various cancer cells, including mast cells [17], melanoma cells [15] and HL-60 leukemia cells [18]. Moreover, eugenol induced apoptosis and inhibited invasion and angiogenesis in a rat model of gastric carcinogenesis induced by MNNG [19]. Interestingly, Eugenol is listed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as “Generally Regarded as Safe” when consumed orally, in unburned form.

In the present paper we present clear evidence that eugenol has potent anti-breast cancer properties both in vitro and in vivo with strong inhibitory effect on E2F1 and survivin.

Methods

Ethics statement

Animal experiments were approved by the KFSH & RC institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) and were conducted according to relevant national and international guidelines. Animals suffered only minimal pain due to needle injection and certain degree of distress related to the growth/burden of the tumor. Euthanasia was performed using CO2 chamber.

Cell lines, chemicals and cell culture

All cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured according to ATCC instructions. The p53 and ER-α status of these cells are mentioned in Table 1. MCF7, T47-D and MDA-MB-231 were maintained in RPMI-1640 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), L-glutamine 1%, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% antibiotic/anti-mycotic (penicillin/streptomycin) (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). MCF 10A cells were cultured in universal medium: (1:1 mixture of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM) and Ham’s F12 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 5% FBS, 1% antibiotic antimycotic, 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF), 100 ng/ml choleratoxin, 10 μg/ml insulin, and 500 ng/ml hydrocortisone). Cells were maintained at 37°C in humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Eugenol (Sigma) was diluted in DMSO and prepared at 1 mM.

Table 1.

Features of used cell lines

| Cell lines | p53 status | ER-α | LC 50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDA-MB-231 |

mutant |

negative |

1.7 |

| MCF7 |

wild-type |

positive |

1.5 |

| T47-D |

wild-type |

positive |

0.9 |

| MCF 10A | wild-type | positive | 2.2 |

Cytotoxicity assay

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 0.5-1.104/well and incubated overnight. The medium was replaced with fresh one containing the desired concentrations of eugenol. After 20 hrs, 10 μl of the WST-1 reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) was added to each well and the plates were incubated for 4 hrs at 37°C. The amount of formazan was quantified using ELISA reader at 450 nm of absorbance.

Cell proliferation analysis

Complete medium (100 μl) containing 2–4 x 103 cells was loaded in each well of the 96-well microtiter E-plates with integrated microelectronic sensor arrays at the bottom of each well. The plate was incubated for at least 30 min in a humidified, 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator, and then was inserted into the Real-Time Cell Electronic Sensing System (RT-CES system, xCELLigence system from Roche Applied Science, originally invented by the US company ACEA Biosciences Inc., San Diego, CA). This allows for label-free and dynamic monitoring of cell proliferation. Cells were monitored for 90 hrs. The electronic readout, cell-sensor impedance is displayed as arbitrary units called cell index, which is defined as Rn-Rb/Rb, with Rn = cell-electrode impedance of the well with the cells and Rb = the background impedance of the well with the media alone.

Cellular lysate preparation

Cells were washed with PBS and then scraped in RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% Sodium deoxycolate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5)), supplemented with protease inhibitors. Lysates were homogenized and then centrifuged at 14000 r.p.m at 4°C for 15 min in an eppendorf micro centrifuge. The supernatant was removed, aliquoted and stored at -80°C.

Immunoblotting

SDS-PAGE was performed using 12% separating minigels and equal amount of proteins were loaded. After protein migration and transfer onto polyvinylidene difluroide membrane (PVDF), the membrane was incubated overnight with the appropriate antibodies:

E2F1 (KH95), Survivin (D-8), NF-κB (F-6), p21 (F-5), Bax (B-9), Bcl-2 (C-2), Cyclin D1 (HD11), caspase-9 (F-7), Cox-2 (29), and β-Catenin (9 F2) were purchased from Santa Cruz, Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA); Cleaved caspase-3 (Asp175), Cleaved caspase-9 (Asp 315), Cleaved-PARP-1 (ASP 214), Cytochrome C and GAPDH were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA).

Visualization of the second antibody was performed using the superSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (THERMO Scientific, Rockford, IL).

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the Tri® Reagent (Sigma) and the yield was quantitated spectrophotometrically. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, single stranded cDNA was synthesized using 200 ng of total RNA, the MMLV Reverse Transcriptase and the oligo dT18 (Roche, San Francisco, CA, USA). The cDNA was amplified for 40 cycles under the following conditions: melting temperature (95°C) for 50 seconds, annealing temperature (54°C) for 50 seconds, and extension temperature (72°C) for 1 min. The RT-PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel at 80 V for an hour. The sequences of the primers were as follow:

β-actin , Fw:5′- CCCAGCACAATGAAGATCAAGATCAT; Rv: 5′-ATCTGCTGGAAGGTGGACAGCGA.

S urvivin , Fw: 5′- CAGAGGAGGCGCCAAGACAG; Rv: 5′-CCTGACGGCGGAAAACGC.

E2F1 , Fw: 5′-ATGTTTTCCTGTGCCCTGAG; Rv: 5′-ATCTGTGGTGAGGGATGAGG.

Quantification of protein and RNA expression levels

The expression levels of RNAs and proteins were measured using the densitometer (BIO-RAD GS-800 Calibrated Densitometer, USA). Films were scanned and protein signal intensity of each band was determined. Next, dividing the obtained value of each band by the values of the corresponding internal control allowed the correction of the loading differences. The fold of induction was determined by dividing the corrected values that corresponded to the treated samples by that of the non-treated one (time 0).

Annexin V/PI and flow cytometry

Cells were treated either with DMSO or eugenol, and then were reincubated in complete media. Detached and adherent cells were harvested 72 hrs later, centrifuged and re-suspended in 1 ml PBS. Cells were then stained by PI and Alexa Fluor 488 annexinV, using Vibrant Apoptosis Assay kit #2 (Molecular probe, Grand Island, NY, USA). Stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of cells was determined by the FACScalibur apparatus and the Cell Quest Pro software from Becton Dickinson, USA. For each cell line 3 independent experiments were performed.

shRNA transfection

The transfection using E2F1-shRNA and control–shRNA was performed using Lipofectamine (Life technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) as previously described [20].

Tumor xenografts

Breast cancer xenografts were created in 10 nude mice by subcutaneous injection of the MDA-MB-231 cells (5.106) into the right leg of each mouse. After the growth of the tumors (about 2 cm3) the animals were randomized into 2 groups to receive intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of eugenol (100 mg/kg) or the same volume of DMSO each 2 days for 4 weeks. Tumor size was measured with a calliper using the following formula (Length X Width X Height).

Results

Eugenol has cytotoxic effect on estrogen positive and negative breast cancer cells

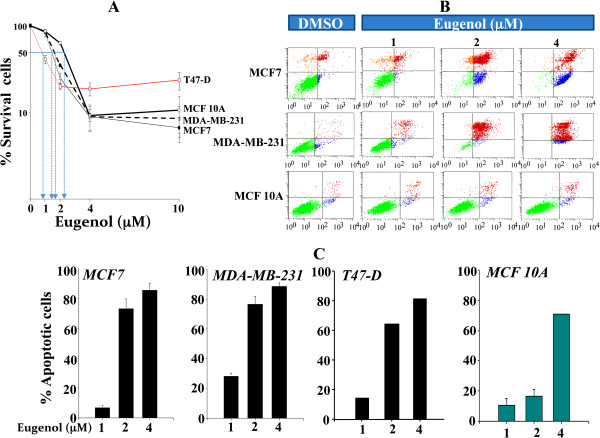

We first investigated the cytotoxic effect of eugenol on different breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231, MCF7 and T47-D) and the non-tumorigenic MCF 10A cell line using the WST-1 assay. Cells were seeded in triplicates into microtiter plates and treated with increasing concentrations of eugenol for 24 hrs, and then the cytotoxic effect was measured. While MCF 10A cells exhibited high resistance to eugenol, with an LC50 (the concentration that leads to 50% survival) of 2.4 μM, breast cancer cells showed clear sensitivity (Figure 1A). The LC50 were 1.7 μM, 1.5 μM and 0.9 μM for MDA-MB-231, MCF7 and T47-D, respectively (Figure 1A, Table 1). This indicates that eugenol has differential cytotoxicity against different breast cancer cell lines, but its less toxic against non-neoplastic breast epithelial cells.

Figure 1.

Cytotoxic effects of eugenol on breast cancer cells. (A) Exponentially growing cells were cultured in 96 well plates and treated with the indicated concentrations of eugenol for 24 hrs. Cell death was analyzed using the WST-1 assay. The arrows indicate the LC50 for each cell line. Error bars represent means ± S.D. (B) Cells were either sham-treated (DMSO) or challenged with the indicated concentrations of eugenol for 72 hrs, and then cell death was assessed by PI/annexinV/flow cytometery. (C) Histograms presenting the proportions of induced apoptosis in the various cell lines. Data are presented as means ± S.D.

Eugenol triggers apoptosis in breast cancer cells through the mitochondrial pathway independently of the estrogen receptor status

Next, we investigated whether eugenol triggers apoptosis in breast cancer cells. To this end, cells were treated with different concentrations of eugenol for 3 days, and then were stained with annexin V/Propidium Iodide (PI), and were sorted by flow cytometry. Figure 1B shows that eugenol triggered essentially apoptosis in both breast cancer cells MCF7 and MDA-MB-231. However, the non-carcinogenic MCF 10A cells exhibited great resistance. Figure 1C shows the proportions of eugenol-induced apoptosis, which was considered as the sum of both early and late apoptosis after deduction of the proportion of spontaneous apoptosis. Interestingly, eugenol effect increased in a dose-dependent manner in the 4 cell lines (Figure 1C). While the effect was only marginal in response to 1 μM, the proportion of apoptotic cells reached 80% in MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 and 65% in T47-D, while it was only 20% in MCF 10A in response to 2 μM eugenol. At 4 μM, eugenol was toxic for MCF 10A as well, and apoptosis reached 70% in these cells, while it was beyond 80% in the three breast cancer cell lines (Figure 1C). This indicates that the eugenol-dependent cytotoxicity is mediated mainly through the apoptotic cell death pathway, with selective effect on breast cancer cells up to 2 μM. Therefore, this concentration was used for the next experiments.

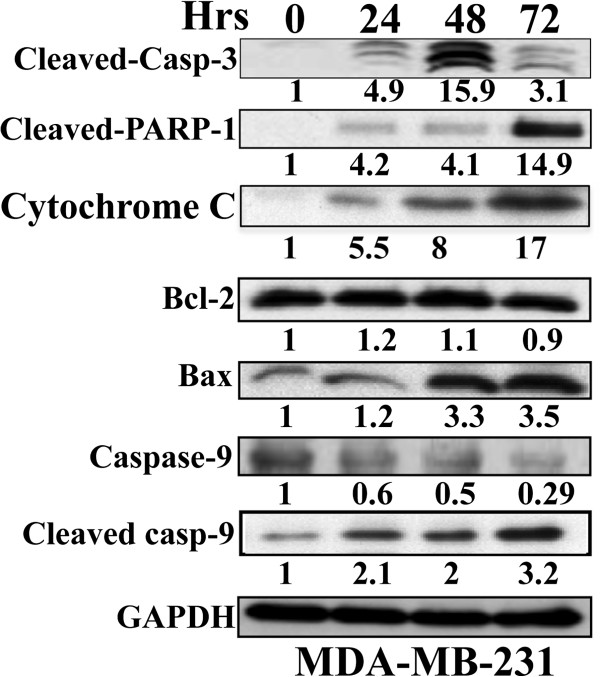

To confirm the induction of apoptosis by eugenol in breast cancer cells and determine the apoptotic route that eugenol activates, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with eugenol (2 μM) and were harvested after different time periods (0, 24, 48 and 72 hrs). Whole cell extracts were prepared and were used to evaluate the levels of different pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins using the immunoblotting technique and specific antibodies. GAPDH was used as internal control. First, we assessed the effect of eugenol on the caspase-3 and PARP-1 proteins (two principal markers of apoptosis). Figure 2 shows that eugenol triggered the cleavage of caspase-3 and PARP-1, which led to significant increase in their active forms, confirming the induction of apoptosis by eugenol in breast cancer cells. Next, we assessed the effect of eugenol on the levels of Bax and Bcl-2 and have found that while the level of Bax increased in a time-dependent manner, the level of Bcl-2 did not change (Figure 2). This resulted in a time-dependent increase in the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio reaching a level 4 fold higher after 72 hrs of treatment, suggesting that eugenol triggers apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway. To confirm this, we assessed the levels of cytochrome C, caspase 9 and its active form in these cells, and showed that while the level of caspase-9 decreased in a time-dependent manner reaching a level more than 3 fold lower after 72 hrs of treatment, the level of cleaved caspase-9 and cytochrome C increased 3 fold, and 17 fold, respectively (Figure 2). Together, these results demonstrate that eugenol triggers apoptosis in breast cancer cells through the internal mitochondrial pathway via Bax increase.

Figure 2.

Eugenol triggers apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with eugenol (2 μM), and then were harvested at the indicated periods of time. Proteins (50 μg) were used for western blot analysis utilizing antibodies against the indicated proteins. The numbers below the bands represent the corresponding expression levels as compared with time 0 and after normalization against GAPDH.

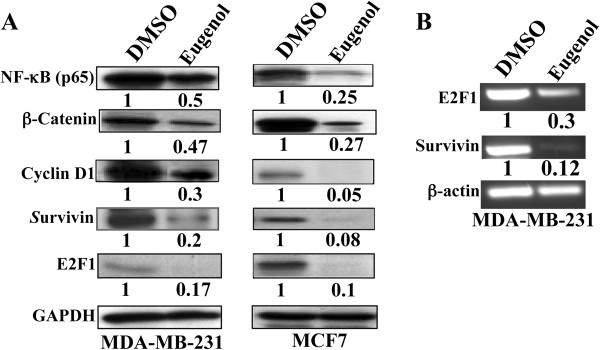

Eugenol is an efficient inhibitor of several cancer promoting genes

To investigate the effect of eugenol on cancer-related genes, MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells were either sham-treated (DMSO) or challenged with eugenol (2 μM) for 24 hrs, and then cell lysates were prepared and protein levels were monitored by immunoblotting. Eugenol-treatment had strong effect on the expression of NF-κB, decreasing its level 2 fold and 3 fold in MDA-MB-231 and MCF7, respectively (Figure 3A). Similar effect was observed on β-catenin, indicating that eugenol could inhibit both major cancer promoting pathways Akt/NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin. To confirm this, we studied the effect of eugenol on the common downstream effector cyclin D1 [21-23]. Indeed, eugenol treatment decreased cyclin D1 level 3 fold in MDA-MB-231 cells and 20 fold in MCF7 cells (Figure 3A). Interestingly, the strongest eugenol inhibitory effect was observed on E2F1 and survivin, a cancer anti-apoptosis marker [24] in both cell lines (Figure 3A). Indeed, after 24 hrs of treatment, the E2F1 and survivin proteins became almost undetectable (Figure 3A). To ascertain the level of action of eugenol on these genes, we investigated the effect on their mRNA levels. To this end, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with eugenol (2 μM) for 24 hrs and total RNA was purified and amplified using RT-PCR and specific primers. Interestingly, eugenol treatment reduced the expression level of both transcripts (Figure 3B). This indicates that eugenol inhibits the expression of these 2 genes at the transcriptional or post-transcriptional level. Therefore, eugenol targets several breast cancer-related signaling pathways, leading to strong inhibition of two important breast cancer oncogenes E2F1 and survivin in both luminal as well as basal like breast cancer cell lines.

Figure 3.

Eugenol suppresses the expression of several oncoproteins. (A) Cells were either sham-treated (DMSO) or challenged with eugenol (2 μM) for 24 hrs. Subsequently, cells were harvested and proteins were used for western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies. The numbers under the bands represent the corresponding expression levels as compared to time 0 and after normalization against GAPDH. (B) DMSO- and eugenol-treated cells (2 μM) were harvested after 4 hrs, and total RNA was extracted and subjected to RT-PCR using specific primers for the indicated genes. The resulting products were electrophorezed in ethidium bromide stained 2% agarose gel. The numbers under the bands represent the corresponding expression levels as compared to control (DMSO) and after normalization against β-actin.

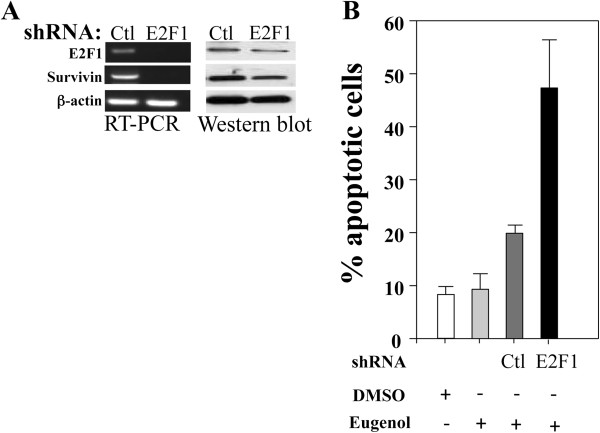

Eugenol triggers apoptosis through E2F1/survivin down-regulation

To elucidate the role of eugenol-related down-regulation of E2F1 and its antiapoptosis target survivin [25] in apoptosis induction in breast cancer cells, we studied the effect of E2F1 specific down-regulation on the cytotoxic effect of eugenol. Therefore, MDA-MB-231 cells were transiently transfected with specific E2F1-shRNA or control-shRNA. Figure 4A shows the effect of E2F1-shRNA on the level of the E2F1 mRNA and protein. Interestingly, like eugenol, E2F1 down-regulation by specific shRNA reduced also the expression level of the survivin mRNA and protein (Figure 4A). This shows that E2F1 controls the expression of survivin in these cells. We next treated MDA-MB-231 cells expressing either control-shRNA or E2F1-shRNA with DMSO or eugenol (1 μM) for 48 hrs. Figure 4B shows that 1 μM eugenol had only marginal effect on MDA-MB-231 cells. Interestingly, E2F1 down-regulation doubled the killing effect of eugenol as compared to the effect on the corresponding control cells (Figure 4B). This suggests that the killing effect of eugenol is mediated through E2F1/survivin down-regulation.

Figure 4.

Eugenol-dependent apoptosis is mediated through down-regulation of E2F1 and survivin. (A) Total RNA and proteins were extracted from MDA-MB-231 cells expressing either control-shRNA or E2F1-shRNA and used for RT-PCR and western blot analysis. (B) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated as shown for 72 hrs, and then apoptosis was assessed by annexinV/PI like in Figure 1B. Data are presented as means ± S.D.

Eugenol inhibits cell proliferation and up-regulates p21WAF1 in breast cancer cells

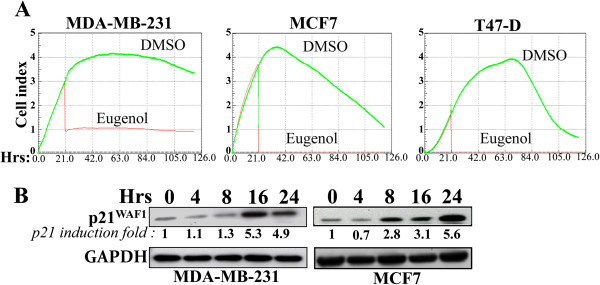

Exponentially growing breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231, MCF7 and T47-D) were seeded in 96-well plates and were either sham-treated with DMSO or challenged with eugenol (2 μM), and then reincubated for 120 hrs. During this time, the real-time cell electronic sensing system was used to monitor cell proliferation. While DMSO-treated cells continued to proliferate, eugenol treatment suppressed cell proliferation in the 3 breast cancer cell lines (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Eugenol inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation and up-regulates p21WAF1. (A) Sub-confluent cells (2–4.103) were either sham-treated or challenged with eugenol (2 μM) for the indicated periods of time, and cell proliferation rate was determined using the Real-Time Cell Electronic Sensing System. (B) MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells were treated with eugenol (2 μM) for the indicated periods of time, and then cell lysates were prepared and 50 μg of proteins were used for western blot analysis utilizing the indicated antibodies.

Next, we evaluated the effect of eugenol on the expression of the versatile cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1 in MDA-MB-231 and MCF7. After treatment with eugenol (2 μM) cells were harvested at different periods of time (0–24 hrs) and immunoblotting was utilized for protein level assessment using specific antibodies. Figure 5B shows that eugenol increased the level of p21WAF1 reaching a level 5 fold higher as compared to the basal level in both cell lines. Therefore, eugenol is a strong inducer of p21WAF1 expression in a p53-independent manner.

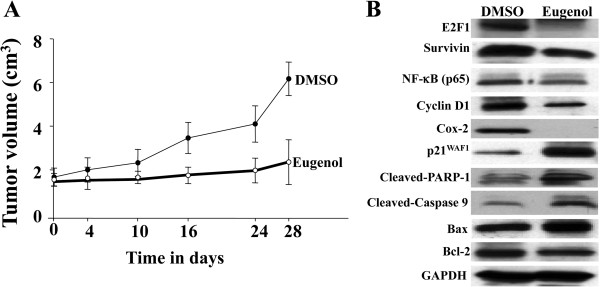

Eugenol inhibits tumor growth of breast tumor xenografts in mice

To study the anti-cancer effect of eugenol in vivo, breast cancer xenografts were created by injecting 5.106 MDA-MB-231 cells subcutaneously into nude mice. When tumors reached a reasonable volume (about 2 cm3), eugenol was given i.p. at a dose of 100 mg/kg each 2 days for 4 weeks. Control animals were treated with DMSO only. Interestingly, in the mock-treated animals, the volume of the tumors increased in a time-dependent manner and became 3 fold bigger than the initial ones (Figure 6A). On the other hand, treatment with eugenol inhibited tumor growth (Figure 6A). This shows that eugenol inhibits the proliferation of breast cancer cells in vivo as well.

Figure 6.

Eugenol inhibits tumor growth and modulates gene expression in vivo. Breast cancer xenografts were created by injecting MDA-MB-231 cells subcutaneously into nude mice. When tumors grew, eugenol was given i.p. at a dose of 100 mg/kg. Control animals were treated with DMSO. (A) Tumor growth. Data are presented as means ± S.D. (B) Following the treatments, tumors were excised and protein extracts were prepared and used for immunoblotting analysis using the indicated antibodies.

Subsequently, we investigated the effect of eugenol on the expression of various cancer-related genes in tumor xenografts. Figure 6B shows that eugenol down-regulated E2F1 and survivin in tumor xenografts as well. Concomitantly, the levels of NF-κB and cyclin D1 also decreased and Cox-2 became undetectable (Figure 6B). Interestingly, like in vitro, eugenol up-regulated p21WAF1 (Figure 6B). Furthermore, we have investigated the effect of eugenol on the expression of apoptosis-related genes and have shown that eugenol increased the levels of Bax, cleaved PARP-1 and the active form of caspase-9, but decreased the level of the anti-apoptosis protein Bcl-2, suggesting eugenol-dependent induction of apoptosis in vivo and confirming the results obtained in vitro (Figure 6B).

Discussion

In the present study we have shown that eugenol, a natural phenolic compound, exhibits strong anti-breast cancer features. Indeed, we present here clear evidence that eugenol could be considered as a potential therapeutic agent for both ER-negative as well as ER-positive breast tumors for the following reasons:

First, eugenol is cytotoxic and triggered apoptosis in great proportion of breast cancer cells, with marginal effect on normal cells in response to 2 μM of eugenol. However, at higher concentration (4 μM), eugenol killed normal cells as well, showing that this molecule may have some toxicity when used as high concentrations.

Eugenol-related apoptosis was mediated through the mitochondrial pathway via Bax increase, and is p53- and ERα-independent since it occurred in p53- and ERα-defective cells, MDA-MB-231 [26]. This effect was mediated through strong down-regulation of E2F1 and its antiapoptosis target survivin [25]. Indeed, specific down-regulation of E2F1 strongly reduced the level of survivin and increased the effect of eugenol on breast cancer cells (Figure 4). Notably, low E2F1 levels were related to favorable breast cancer outcome [27]. On the other hand, E2F1 expression was related with poor survival of lymph node-positive breast cancer patients treated with fluorouracil, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide [28]. This indicates that high E2F1 levels reduce the response of breast tumors to therapy. Similarly, while survivin expression has been found to confer resistance to chemotherapy and radiation, targeting survivin in experimental models improved survival [29]. Thereby, the fact that eugenol can inhibit both E2F1 and survivin in vitro and in tumor xenografts, indicates that eugenol could be used to consolidate the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer patients, especially the clinically aggressive ER-negative types, whose prognosis is still poor and clinically characterized as more aggressive and less responsive to standard treatments [30,31].

Second, eugenol is a potent inhibitor of cell proliferation, may be through inhibition of E2F1 and great increase in the level of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1in vitro and in tumor xenografts. E2F1 is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of several genes involved in G1 to S phase transition [32]. In a previous study it has been shown that eugenol inhibits cell proliferation in melanoma cells through inhibition of E2F1 [15]. p21 induction in p53-defective MDA-MB-231 cells, suggests the ability of eugenol to induce p21WAF1 through p53-independent mechanism. Overexpression of p21WAF1 can block both the G1/S and G2/M transitions of the cell cycle [33]. Furthermore, p21WAF1 is a modulator of apoptosis in a number of systems [34-36]. Therefore, the strong eugenol-dependent up-regulation of p21WAF1 in a p53-independent manner could be of great value for the inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and the induction of cell death in various p53-defective breast tumors, including the triple negative form of the disease where p53 deficiency is observed in up to 44% [37].

Third, eugenol down-regulated several onco-proteins known to be highly expressed in breast cancer cells and tissues, such as NF-κB, β-catenin, cyclin D1, Bcl-2 and survivin. Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway plays a major role in breast carcinogenesis. NF-κB up-regulation is implicated not only in tumor growth and progression, but also in the resistance to chemo- and radiotherapies. Several studies have documented the elevated activity of this protein in breast cancer cells [38,39], which makes it an excellent target for cancer therapy [40,41]. In a recent study, it has been shown that eugenol can inhibit cell proliferation via NF-κB suppression in a rat model of gastric carcinogenesis [42]. The other important breast cancer signaling pathway is the Wnt/β-catenin, which is another transcription factor that has been found highly expressed in various types of cancer, including breast carcinomas [43,44], and is particularly activated in triple negative breast cancer. Therefore, the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway constitutes an important potential therapeutic target in the treatment of breast cancer, especially the triple negative form of the disease [45].

The activation of these 2 signaling pathways leads to the up-regulation of cyclin D1, which is a common downstream effector protein. Cyclin D1 is an oncogene that is over-expressed in about 50% of all breast cancer cases [46], and its down-regulation is an important target in breast cancer therapy [47]. Therefore, eugenol-related down-regulation of NF-κB and β-catenin and their common downstream target cyclin D1 could have a great inhibitory effect on breast cancer growth. Importantly, the inhibitory effect of eugenol on these onco-proteins was also observed in vivo in tumor xenografts (Figure 6).

Conclusions

Eugenol could constitute a potent anti-breast cancer agent with less side effects than the classical chemotherapeutic agents, through targeting the E2F1/survivin oncogenic pathway. Therefore, eugenol warrants further investigations for its potential use as chemotherapeutic agent against ER-negative and also p53-defective tumors, which are still of poor prognosis.

Abbreviations

ATCC: American type culture collection; DMSO: Dimethyl sulfoxide; FBS: Fetal bovine serum; RT-PCR: Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; shRNA: Short hairpin RNA.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

IA carried out the majority of the experiments. AR conceived the project. AA conceived the project, supervised research and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Ibtehaj Al-Sharif, Email: ialsharif@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Adnane Remmal, Email: adnaneremmal@gmail.com.

Abdelilah Aboussekhra, Email: aboussekhra@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Comparative Medicine staff for their help with animals. We also thank P. S. Manogaran for his help with the flow cytometry experiment. This work was performed under the RAC proposal # 2100013.

References

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2011;13(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulder S, Hortobagyi GN. Advances in the treatment of breast cancer. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;13(1):26–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davar D, Beumer JH, Hamieh L, Tawbi H. Role of PARP inhibitors in cancer biology and therapy. Curr med chem. 2012;13(23):3907–3921. doi: 10.2174/092986712802002464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dona F, Chiodi I, Belgiovine C, Raineri T, Ricotti R, Mondello C, Scovassi AI. Poly (ADP-ribosylation) and neoplastic transformation: effect of PARP inhibitors. Curr pharm biotechnol. 2012. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Craig W, Beck L. Phytochemicals: health protective effects. Can J Diet Pract Res. 1999;13(2):78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig WJ. Phytochemicals: guardians of our health. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;13(10 Suppl 2):S199–204. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(97)00765-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg AK, Buchholz TA, Aggarwal BB. Chemosensitization and radiosensitization of tumors by plant polyphenols. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;13(11–12):1630–1647. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann J. Natural products in cancer chemotherapy: past, present and future. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;13(2):143–148. doi: 10.1038/nrc723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomasset SC, Berry DP, Garcea G, Marczylo T, Steward WP, Gescher AJ. Dietary polyphenolic phytochemicals–promising cancer chemopreventive agents in humans? a review of their clinical properties. Int J Cancer. 2007;13(3):451–458. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramod K, Ansari SH, Ali J. Eugenol: a natural compound with versatile pharmacological actions. Nat prod commun. 2010;13(12):1999–2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benencia F, Courreges MC. In vitro and in vivo activity of eugenol on human herpesvirus. Phytother Res. 2000;13(7):495–500. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200011)14:7<495::AID-PTR650>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondak VK, Sabel MS, Mule JJ. Allogeneic and autologous melanoma vaccines: where have we been and where are we going? Clin Cancer Res. 2006;13(7 Pt 2):2337s–2341s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stich HF, Stich W, Lam PP. Potentiation of genotoxicity by concurrent application of compounds found in betel quid: arecoline, eugenol, quercetin, chlorogenic acid and Mn2+ Mutat Res. 1981;13(4):355–363. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(81)90058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slamenova D, Horvathova E, Wsolova L, Sramkova M, Navarova J. Investigation of anti-oxidative, cytotoxic, DNA-damaging and DNA-protective effects of plant volatiles eugenol and borneol in human-derived HepG2, Caco-2 and VH10 cell lines. Mutat Res. 2009;13(1–2):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh R, Nadiminty N, Fitzpatrick JE, Alworth WL, Slaga TJ, Kumar AP. Eugenol causes melanoma growth suppression through inhibition of E2F1 transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;13(7):5812–5819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisano M, Pagnan G, Loi M, Mura ME, Tilocca MG, Palmieri G, Fabbri D, Dettori MA, Delogu G, Ponzoni M. et al. Antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic activity of eugenol-related biphenyls on malignant melanoma cells. Mol cancer. 2007;13:8. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park BS, Song YS, Yee SB, Lee BG, Seo SY, Park YC, Kim JM, Kim HM, Yoo YH. Phospho-ser 15-p53 translocates into mitochondria and interacts with Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL in eugenol-induced apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2005;13(1):193–200. doi: 10.1007/s10495-005-6074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada N, Hirata A, Murakami Y, Shoji M, Sakagami H, Fujisawa S. Induction of cytotoxicity and apoptosis and inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression by eugenol-related compounds. Anticancer Res. 2005;13(5):3263–3269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikandan P, Murugan RS, Priyadarsini RV, Vinothini G, Nagini S. Eugenol induces apoptosis and inhibits invasion and angiogenesis in a rat model of gastric carcinogenesis induced by MNNG. Life Sci. 2010;13(25–26):936–941. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mohanna MA, Al-Khalaf HH, Al-Yousef N, Aboussekhra A. The p16INK4a tumor suppressor controls p21WAF1 induction in response to ultraviolet light. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;13(1):223–233. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands TM, Pechenkina IV, Hatsell S, Cowin P. Beta-catenin and cyclin D1: connecting development to breast cancer. Cell Cycle. 2004;13(2):145–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttridge DC, Albanese C, Reuther JY, Pestell RG, Baldwin AS Jr. NF-kappaB controls cell growth and differentiation through transcriptional regulation of cyclin D1. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;13(8):5785–5799. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz M, Krappmann D, Eichten A, Heder A, Scheidereit C, Strauss M. NF-kappaB function in growth control: regulation of cyclin D1 expression and G0/G1-to-S-phase transition. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;13(4):2690–2698. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altieri DC. Survivin, cancer networks and pathway-directed drug discovery. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;13(1):61–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Saavedra HI, Holloway MP, Leone G, Altura RA. Aberrant regulation of survivin by the RB/E2F family of proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;13(39):40511–40520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404496200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix M, Toillon RA, Leclercq G. p53 and breast cancer, an update. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13(2):293–325. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuaroqueaux V, Urban P, Labuhn M, Delorenzi M, Wirapati P, Benz CC, Flury R, Dieterich H, Spyratos F, Eppenberger U. et al. Low E2F1 transcript levels are a strong determinant of favorable breast cancer outcome. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;13(3):R33. doi: 10.1186/bcr1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Park K, Bae BN, Kim KH, Kim HJ, Kim YD, Kim HY. E2F1 expression is related with the poor survival of lymph node-positive breast cancer patients treated with fluorouracil, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;13(1):11–16. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000003843.53726.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha K, Shukla M, Pandey M. Survivin expression and targeting in breast cancer. Surgical oncology. 2012;13(2):125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khramtsov AI, Khramtsova GF, Tretiakova M, Huo D, Olopade OI, Goss KH. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway activation is enriched in basal-like breast cancers and predicts poor outcome. Am J Pathol. 2010;13(6):2911–2920. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey L, Winer E, Viale G, Cameron D, Gianni L. Triple-negative breast cancer: disease entity or title of convenience? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;13(12):683–692. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iaquinta PJ, Lees JA. Life and death decisions by the E2F transcription factors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;13(6):649–657. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotto GP. p21(WAF1/Cip1): more than a break to the cell cycle? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;13(1):M43–56. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(00)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartel AL, Tyner AL. The role of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 in apoptosis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;13(8):639–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman ES, Moroni MC, Helin K. The role of p53 and pRB in apoptosis and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;13(1):60–66. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(01)00265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanelle J, Putzer BM. E2F1-induced apoptosis: turning killers into therapeutics. Trends Mol Med. 2006;13(4):177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, Karaca G, Troester MA, Tse CK, Edmiston S. et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the carolina breast cancer study. JAMA. 2006;13(21):2492–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Karin M. NF-kappaB in mammary gland development and breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2003;13(2):215–223. doi: 10.1023/A:1025905008934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffner MC, Berlato C, Doppler W. Exploiting our knowledge of NF-kappaB signaling for the treatment of mammary cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2006;13(1):63–73. doi: 10.1007/s10911-006-9013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Waes C. Nuclear factor-kappaB in development, prevention, and therapy of cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(4):1076–1082. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Jeon YT, Kim SH, Song YS. NF-kappaB as a potential molecular target for cancer therapy. Biofactors. 2007;13(1):19–35. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520290103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikandan P, Vinothini G, Vidya Priyadarsini R, Prathiba D, Nagini S. Eugenol inhibits cell proliferation via NF-kappaB suppression in a rat model of gastric carcinogenesis induced by MNNG. Invest New Drugs. 2011;13(1):110–117. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Dey A. Wnt signaling and cancer development: therapeutic implication. Neoplasma. 2008;13(3):165–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad CP, Gupta SD, Rath G, Ralhan R. Wnt signaling pathway in invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast: relationship between beta-catenin, dishevelled and cyclin D1 expression. Oncology. 2007;13(1–2):112–117. doi: 10.1159/000120999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King TD, Suto MJ, Li Y. The wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway: a potential therapeutic target in the treatment of triple negative breast cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2012;13(1):13–18. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartkova J, Lukas J, Muller H, Strauss M, Gusterson B, Bartek J. Abnormal patterns of D-type cyclin expression and G1 regulation in human head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;13(4):949–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Trent S, Ionescu-Tiba V, Lan L, Shioda T, Sgroi D, Schmidt EV. Identification of cyclin D1- and estrogen-regulated genes contributing to breast carcinogenesis and progression. Cancer Res. 2006;13(24):11649–11658. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]