Abstract

A 67-year-old man underwent surgery under general anaesthesia to obtain a biopsy from a tumour in the left maxillary sinus. Before the procedure a mucosal detumescence containing epinephrine and cocaine was applied onto the nasal mucosa. Shortly after termination of anaesthesia the patient developed tachycardia and an abrupt rise in blood pressure followed by a drop to critical levels. The patient turned pale and clammy but denied chest pain at any time. An ECG showed inferolateral ST-segment elevation, and troponin T was elevated at 0.773 ng/mL. An acute coronary angiography demonstrated normal coronary arteries; however, left ventriculography showed apical ballooning of the left ventricle, and the diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy was made. This was confirmed by a subsequent transthoracic echocardiography. Four days later the patient had complete resolution of the symptoms, and a new echocardiography showed normalisation of the left ventricular systolic function with no signs of apical ballooning.

Background

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TC) is a reversible cardiomyopathy characterised by transient systolic dysfunction of the left ventricle in the absence of coronary artery obstruction. TC is most frequently seen in postmenopausal women and often associated with an acute medical illness or with emotional or physical stress.1––3 TC usually presents with chest pain and ECG signs of acute myocardial ischaemia accompanied by an often modest increase in cardiac biomarkers. The condition thus mimics acute myocardial infarction; however, the coronary angiogram shows no significant coronary artery disease, and a left ventriculography or transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) will reveal left ventricular apical akinesis or hypokinesis and basal hypercontractility producing the characteristic apical ballooning (hence the synonym ‘apical ballooning syndrome’). TC is seen in 1–2% of patients admitted with suspected acute myocardial infarction,4 and full recovery is usually seen with conventional treatment for congestive heart failure. TC is believed to be caused by a catecholamine storm stunning the myocardium.5 We report the first case of TC induced by an epinephrine and cocaine containing agent used for mucosal detumescence.

Case presentation

A 67-year-old man was admitted for elective biopsy of a tumour in the left maxillary sinus. The procedure was performed under general anaesthesia. The patient had a history of grade I follicular lymphoma managed conservatively with watchful waiting, but transformation to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma was suspected. Preoperative medications included only a magnesium supplement for nocturnal leg cramps. The patient had no risk factors for coronary artery disease and had no cardiac history. During the procedure, the so-called Moffat's solution, an epinephrine and cocaine containing agent used for mucosal detumescence, was applied onto the nasal mucosa with pads for about 5 min with the head tilted backwards. The surplus was suctioned from the nasopharynx after removal of the pads. In total, 8 mL was applied, corresponding to 3.2 mg epinephrine and 320 mg cocaine. The procedure was uncomplicated, but shortly after termination of anaesthesia the patient became pale, clammy and nauseated. He denied chest pain or other angina equivalents at any time.

Investigations

About 5 min after the procedure the patient developed high blood pressure (227/121 mm Hg) and tachycardia (pulse 135 bpm). This was followed by a rapid decline in blood pressure over the next 30 min to 85/55 mm Hg (pulse 85 bpm). Routine haematological and biochemical investigations were within normal values apart from stress-induced mildly elevated C reactive protein at 24 mg/L. The troponin T at presentation was elevated at 0.773 ng/mL. Arterial blood gas analysis showed an SpO2 of 91% (FiO2 40%).

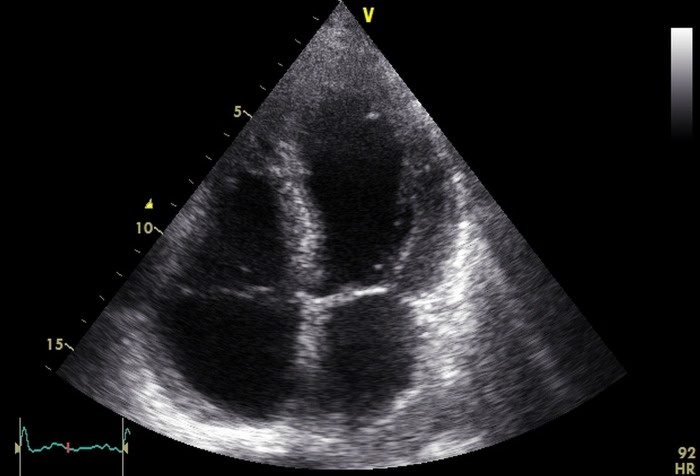

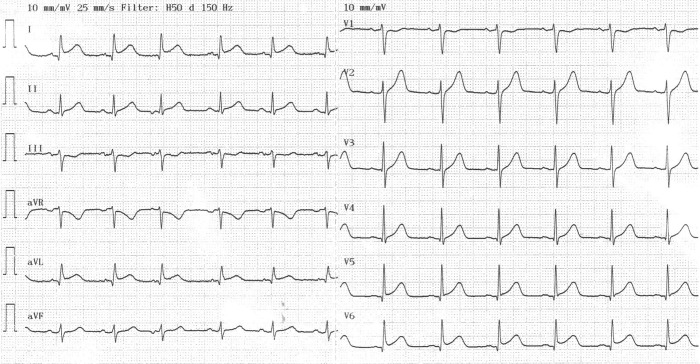

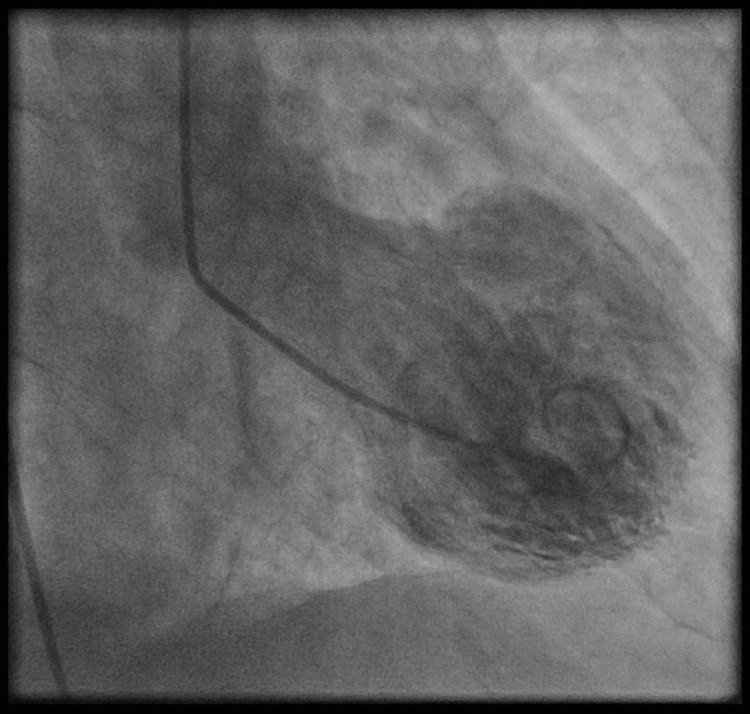

An ECG showed ST-segment elevation in the inferior and lateral leads (figure 1). The patient was immediately transferred to the department of cardiology, where an acute coronary angiography demonstrated normal coronary arteries; however a left ventriculography revealed the characteristic apical ballooning of TC (figure 2). This was confirmed on a subsequent TTE (figure 3), which showed anteroapical hypokinesis, basal hyperkinesis, a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 25% and tricuspid regurgitation with a systolic transtricuspid pressure gradient of 47 mm Hg.

Figure 1.

The first ECG recording after surgery showing ST-segment elevation in the inferior (II and III) and lateral (I, aVL and V3–V6) leads.

Figure 2.

Left ventriculogram with apical hypokinesis (ballooning) and basal hyperkinesis.

Figure 3.

Echocardiogram in apical four-chamber view during the systolic phase, demonstrating apical ballooning and hyperkinesis in the basal segments.

Differential diagnosis

TC was suspected from the reaction to Moffat's solution and the fact that the patient had no cardiac history. However, other differential diagnoses of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) were considered. Most importantly, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction was ruled out given the normal coronary angiography. Also, pulmonary embolism (PE) was considered since the patient had undergone surgery, and we found signs of mild pulmonary hypertension in the TTE and an SpO2 of 91%. With no dyspnoea, an otherwise normal arterial blood gas analysis and no specific signs of PE in the ECG or TTE a significant PE was unlikely after all.

Treatment

The patient was treated with an ACE inhibitor and oral furosemide as part of congestive heart failure management until the LVEF normalised. Furthermore, we prescribed a low-molecular weight heparin (dalteparin) in weight adjusted therapeutic doses until the left ventricular function had normalised to prevent the formation of mural thrombi.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient's symptoms improved quickly and a control TTE 4 days later demonstrated complete recovery of left ventricular systolic function with no apical ballooning. Low-molecular weight heparin, ACE inhibitor and furosemide were discontinued and the patient was discharged in good health.

Discussion

We report the first case of iatrogenic TC induced by local application of Moffat's solution onto the nasal mucosa during surgery in general anaesthesia. Although we cannot be sure that a causal relationship exists, the close temporal association between the administration of Moffat's solution and the rapid onset of symptoms suggests that the combination of cocaine and epinephrine was the trigger for the development of TC. The observed fluctuations in blood pressure were presumably due to the systemic effects of epinephrine and cocaine causing an initial abrupt rise in blood pressure followed by apical ballooning causing subsequent hypotension.

Regardless of the underlying trigger the prevailing pathophysiological theory of TC is a surge in catecholamines causing stunning of the myocardium.5 Supporting this is the fact that plasma catecholamine levels are higher at presentation in patients with TC than in those with myocardial infarction.5 The mechanism by which catecholamines cause TC is unknown, but several theories exist.

Surges of catecholamines may induce myocardial injury directly via cyclic AMP-–mediated calcium overload or indirectly due to catecholamine-induced endothelial dysfunction and associated damage to underlying myocytes.6

Myocytes in the left ventricular apex are thought to be particularly sensitive to excessive levels of catecholamines due to higher density of β-adrenoceptors.7 8

Cocaine use is notoriously associated with myocardial infarction, malignant hypertension, myocarditis and cardiac arrhythmias. It acts as a powerful sympathomimetic agent by blocking the presynaptic reuptake of norepinephrine, epinephrine and dopamine producing high level of these neurotransmitters at the postsynaptic receptors.9 Furthermore, cocaine activates platelets and promotes thrombus formation.10

Therefore, it seems plausible that cocaine in this case intensifies the effects of epinephrine causing a synergetic impact on the myocardium. This could explain why locally applied epinephrine leading to a presumably small serum concentration might cause TC in susceptible patients.

Several case reports exist on TC caused by systemic administration of epinephrine,11––16 whereas only a single case report describes TC after nasal application of epinephrine.17 To our knowledge, only two case reports have described TC caused by cocaine abuse.18 19 In this particular case epinephrine and cocaine were presumed to work in concert resulting in the development of TC.

After the use of epinephrine and cocaine for mucosal detumescence it is important to consider the possibility of TC when patients present with symptoms of ACS, and the ECG shows signs of acute ischaemia. Awareness of this association and early investigations (including a coronary angiography) can rule out ACS and thus prevent unnecessary and, in the setting of surgery, dangerous use of antithrombotic agents as part of initial ACS management.

Learning points.

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TC) is a rare condition that clinically mimics acute myocardial infarction and is characterised by a transient dysfunction of the apical portions of the left ventricle and often precipitated by intense physical or emotional stress.

A coronary angiography is required to rule out coronary artery disease.

Moffat's solution is an epinephrine and cocaine containing agent for mucosal detumescence used in surgery of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. In susceptible patients it can be harmful and trigger the development of TC.

This case supports the prevailing pathophysiological theory of TC being caused by a catecholamine surge and subsequent stunning of the myocardium.

TC is reversible and prognosis is generally good.

Footnotes

Contributors: JS wrote the initial draft. JS, MP, MH and EHM participated in collecting the patient data (pictures and patient history), reviewing the literature, interpretation of clinical findings, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approval of the final version.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, et al. Systematic review: transient left ventricular apical ballooning: a syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:858–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gianni M. Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1523–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akashi YJ, Goldstein DS, Barbaro G, et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a new form of acute, reversible heart failure. Circulation 2008;118:2754–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurowski V. Apical and midventricular transient left ventricular dysfunction syndrome (Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy)* frequency, mechanisms, and prognosis. Chest 2007;132:809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JAC, et al. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med 2005;352:539–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mann DL, Kent RL, Parsons B, et al. Adrenergic effects on the biology of the adult mammalian cardiocyte. Circulation 1992;85:790–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paur H, Wright PT, Sikkel MB, et al. High levels of circulating epinephrine trigger apical cardiodepression in a beta2-adrenergic receptor/Gi-dependent manner: a new model of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2012;126:697–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyon AR, Rees PS, Prasad S, et al. Stress (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy—a novel pathophysiological hypothesis to explain catecholamine-induced acute myocardial stunning. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2008;5:22–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lange RA, Hillis LD. Cardiovascular complications of cocaine use. N Engl J Med 2001;345:351–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heesch CM, Wilhelm CR, Ristich J, et al. Cocaine activates platelets and increases the formation of circulating platelet containing microaggregates in humans. Heart 2000;83:688–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magri CJ, Fava S, Felice H. Inverted takotsubo cardiomyopathy secondary to epinephrine injection. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2011;72:646–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harle T, Kronberg K, Nef H, et al. Inverted Takotsubo cardiomyopathy following accidental intravenous administration of epinephrine in a young woman. Clin Res Cardiol 2011;100:471–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Litvinov IV, Kotowycz MA, Wassmann S. Iatrogenic epinephrine-induced reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: direct evidence supporting the role of catecholamines in the pathophysiology of the “broken heart syndrome”. Clin Res Cardiol 2009;98:457–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khoueiry G, Abi Rafeh N, Azab B, et al. Reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the setting of anaphylaxis treated with high-dose intravenous epinephrine. J Emerg Med 2013;44:96–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saeki S, Matsuse H, Nakata H, et al. [Case of bronchial asthma complicated with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy after frequent epinephrine medication]. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi 2006;44:701–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patankar GR, Donsky MS, Schussler JM. Delayed takotsubo cardiomyopathy caused by excessive exogenous epinephrine administration after the treatment of angioedema. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2012;25:229–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff von F, Abdel-Aty H, Schulz-Menger J. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy after nasal application of epinephrine—a magnetic resonance study. Int J Cardiol 2010;145:308–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arora S, Alfayoumi F, Srinivasan V. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning after cocaine use: is catecholamine cardiotoxicity the pathologic link? Mayo Clinic Proc 2006;81:829–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daka MA, Khan RS, Deppert EJ. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning after a cocaine binge. J Invasive Cardiol 2007;19:E378–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]