Abstract

Objectives

Examine the probability of new active substances (NASs) approved in Canada between 1 January 1997 and 31 March 2012 acquiring a serious postmarket safety warning.

Design

Cohort study.

Data sources

Annual reports of the Therapeutic Products Directorate and the Biologic and Genetic Therapies Directorate; evaluations of therapeutic innovation from the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board and Prescrire International; MedEffect Canada website.

Interventions

Postmarket regulatory safety warning or withdrawal from market due to safety reasons.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Compare the probability of acquiring a postmarket safety warning in Canada in four different groups of drugs: (1) traditional medications versus biologics; (2) medications that offer significant new therapeutic benefits versus those that do not. Determine how well the type of review that an NAS received from Health Canada predicted the product's postmarket therapeutic value.

Results

The probability of a traditional NAS acquiring a serious safety warning and/or being withdrawn was 29.9% (95% CI 21.8% to 40.2%) vs 27.3% (95% CI 18.2% to 39.7%) for an NAS of biological origin (p=0.47, log-rank test). For medications that were significant therapeutic advances the probability was 40.2% (95% CI 24.5% to 60.9%) vs 33.9% (95% CI 26.4% to 42.7%) for those that were not (p=0.18, log-rank test). Health Canada was 77.4% accurate in predicting the therapeutic importance of an NAS.

Conclusions

There was no difference in postmarket regulatory safety action between traditional medications and biologics and no difference between drugs with significant therapeutic benefits and those without. Although these results draw on Canadian data, they are likely to be relevant internationally. Further research should assess whether the current level of premarket safety evaluation is acceptable.

Keywords: CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Systematic study of the postmarket regulatory safety warnings comparing groups of drugs: biologics versus traditional medicines and drugs with significant therapeutic advances versus drugs without significant therapeutic advances.

Comparison of premarket regulatory evaluation of therapeutic advance with postmarket evaluation.

Unclear what criteria Health Canada uses to decide to issue serious safety warnings.

Unknown date on which a drug actually marketed as opposed to date approved.

Postmarket therapeutic evaluation of all new drugs could not be determined.

Presence of a postmarket safety warning does not necessarily equate with the overall safety of a drug.

Introduction

Drug safety is becoming a topic of increasing concern in Canada. In July 2008, the federal government officially launched the Drug Safety and Effectiveness Network (DSEN) designed to connect researchers throughout Canada in a virtual network to conduct postmarket drug research1 and stimulate research to study the impact of drug use in the real-world setting.2 In 2010, the Health Council of Canada released a discussion paper that drew on international best practices for recommendations about how Canada could improve its developing system of active pharmacosurveillance.3 In 2011, the Auditor General reported that Health Canada is slow to assess potential safety issues and can take more than 2 years to provide Canadians with new safety information.4 Most recently, legislation has been introduced that would give Health Canada the power to order additional safety testing for drugs already on the market.5

The increased focus on drug safety comes from a number of directions. In the USA, adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are estimated to result in between 76 000 and 137 000 deaths/year, making ADRs the fourth to sixth leading annual cause of death.6 The Institute for Safe Medication Practices puts the number of annual deaths in the USA due to ADRs at 128 000 based on reports to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).7 Since the Lazarou et al estimate was made in the late 1990s, the reported serious adverse drug events increased 2.6-fold from 1998 to 2005 and fatal adverse drug events increased 2.7-fold during the same period while the total number of outpatient prescriptions went up by only 40%.8 While there are relatively few drugs withdrawn from the market for safety reasons,9 large numbers of people have been exposed to some of these products. In 2003, the year before rofecoxib (Vioxx) was removed from the market, it was the 10th most frequently prescribed medication in Canada.10

A recent analysis of drug safety in Canada found that almost one in four new active substances (NASs) approved between 1995 and 2010 either had a serious safety warning or was removed from the market for safety reasons (An NAS is a molecule never previously marketed in any form in Canada. This designation is given to all molecules meeting the definition and therefore should not be seen as creating a division between ‘new’ and ‘old’ drugs). This figure increased to more than one in three for products that received a priority review, that is, products that Health Canada felt might provide an effective treatment of a disease for which no drug is presently marketed or a significant increase in efficacy and/or significant decrease in risk over existing therapies.11 Priority reviews have a timeline of 180 days versus the standard timeline of 300 days.12

This study compares postmarket regulatory safety action in four groups of drugs: (1) traditional medications (those derived from chemical manufacturing) and biologics; (2) medications that offer significant new therapeutic benefits and those that do not. Biologics are large molecules synthesised from living organisms and typically administered intravenously. As such, they may have a significantly different safety profile compared to traditional small molecule medications that come from chemical synthesis and are usually ingested orally. Regulators may be willing to approve drugs that offer significant therapeutic advances with more uncertainty about their safety compared to drugs that are not a significant therapeutic advance.

Specifically, this study attempts to reject the following two null hypotheses: (1) there is no difference in the postmarket safety profile of traditional versus biological medications, (2) there is no difference in the postmarket safety profile of drugs with significant therapeutic advances versus those without. A secondary objective was to determine how well the type of review that an NAS received from Health Canada predicted the product's postmarket therapeutic value.

Methods

A list of NAS approved between 1 January 1997 and 31 March 2012 was compiled from the annual reports of the Therapeutic Products Directorate (TPD) and the Biologic and Genetic Therapies Directorate (BGTD; henceforth collectively referred to as the TPD)—available by directly contacting the directorates at publications@hc-sc.gc.ca. For each product, the following information was abstracted: generic name, brand name, manufacturer, indication, date of notice of compliance (NOC—marketing authorisation), type of review (priority or standard) and type of product (traditional or biological). The TPD annual reports only gave the type of product (traditional or biological) from 2000 onwards.

Two sources were used to determine the postmarket therapeutic value of the NAS: the annual reports of the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) available online from 2003 to 2011 at http://www.pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca/english/View.asp?x=91 and for previous years by directly contacting the PMPRB at pmprb@pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca and the online reviews published by Prescrire International up to 14 February 2013 http://english.prescrire.org/en/. These sources were chosen because their evaluations are unambiguous and therefore do not require any subjective interpretation and they are both available in English.

The PMPRB is a federal agency that is responsible for calculating the maximum introductory price for all new patented medications introduced into the Canadian market. As part of the process of determining the price, its Human Drug Advisory Panel determines the therapeutic value of each product it reviews. Up until the end of 2009, NASs were classified into two groups: (1) breakthroughs or substantial improvement and (2) moderate, little or no therapeutic improvement. Since 2010, NASs are classified as breakthrough or substantial improvement, moderate improvement (primary or secondary) and slight or no improvement. For the purpose of this study, products that were deemed breakthrough and substantial improvement were termed ‘significant therapeutic advance’ and products in other groups were termed ‘no therapeutic advance’. The change in the PMPRB system starting in 2010 was meant to provide a finer gradation in the ‘moderate, little or no therapeutic improvement’ group and as such did not affect the dichotomous classification used here between ‘significant therapeutic advance’ and ‘no therapeutic advance’. In some cases, the PMPRB annual reports indicated that the therapeutic value of the product was still being determined, and in those cases the PMPRB was contacted directly to determine the final classification.

If the PMPRB had not considered a product, then its therapeutic value was determined from Prescrire evaluations. Prescrire rates products using the following categories: bravo (major therapeutic innovation in an area where previously no treatment was available); a real advance (important therapeutic innovation but has limitations); offers an advantage (some value but does not fundamentally change the present therapeutic practice); possibly helpful (minimal additional value and should not change prescribing habits except in rare circumstances); nothing new (may be a new molecule but is superfluous because it does not add to clinical possibilities offered by previously available products); not acceptable (without evident benefit but with potential or real disadvantages); and judgement reserved (decision postponed until better data and more thorough evaluation). The first three Prescrire categories were defined as a significant therapeutic advance and the other Prescrire categories (except judgement reserved) were defined as no therapeutic advance. Previous work has shown a moderate level of agreement between the therapeutic evaluations from the PMPRB and Prescrire.13

Safety warnings and drug withdrawals for the period 1 January 1997 to 31 December 2012 were identified through advisories for health professionals on the MedEffect Canada website http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/medeff/advisories-avis/prof/index-eng.php. For each safety advisory or notice of withdrawal of a product, the date and reason were recorded. All serious safety advisories (those using bolded black print or boxed warnings) were included except for those dealing with the withdrawal of a specific batch or lot number due to manufacturing problems or those issued because of misuse of a drug (eg, an unapproved use) or medication errors (eg, a warning about remembering to remove a transdermal patch before applying a second one). When necessary, notices on the MedEffect website were supplemented by searching on the product name in the Drug Product Database (DPD) http://webprod3.hc-sc.gc.ca/dpd-bdpp/index-eng.jsp. The DPD contains product-specific information on drugs approved for use in Canada as well as all products discontinued since 1996.

Troglitazone was approved but never marketed in Canada because of a dispute about its introductory price. There was no information about revocation of its NOC on the MedEffect website. The drug was removed from the US market in March 2000 and 15 March 2000 was arbitrarily used as its withdrawal date in Canada. It was retained in the analysis because it was a product that was approved and then later shown to have side effects serious enough that it needed to be withdrawn. The TPD annual reports list infliximab as two separate NASs since it was approved for two different indications—Crohn's disease and rheumatoid arthritis—and therefore it is included twice.

The time between receipt of an NOC and a safety warning and/or withdrawal from the market was calculated in days. If a drug received more than one serious safety warning, only the time to the first warning was used. Medians are reported for the time from NOC to serious safety warnings and/or withdrawal as these values are not normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were calculated separately for the following comparisons: (1) biological versus traditional NASs and (2) NASs that were therapeutic advances versus those that were not.

Health Canada gives a shorter priority review to drugs that it believes show evidence of providing a significant increase in efficacy or a significant decrease in side effects compared to other available agents for a serious, life threatening or severely debilitating illness or condition, that is, drugs that Health Canada judges as providing significant therapeutic gains.12 Health Canada's accuracy in evaluating an NAS's therapeutic benefit was determined by comparing the review status given to the drug (priority vs standard) with the therapeutic evaluation from the PMPRB or Prescrire.

There were no power calculations as the entire population of NAS was evaluated rather than just a sample. Calculations were carried out using Excel 2011 for Macintosh (Microsoft) and Prism V.6.0 (GraphPad Software).

Results

Four hundred and six NASs were approved from 1 January 1997 to 31 March 2012. Eighty-seven (21.4%) were subject to either a serious safety warning and/or were withdrawn for safety reasons: 72 (17.7%) had only serious safety warnings and 15 (3.7%) were withdrawn (8 had safety warnings first and 7 were withdrawn without any prior safety warning; online supplementary appendix lists all drugs with safety warnings and/or withdrawals). A notice that one product, gatifloxacin, had been withdrawn from the market never appeared on the MedEffect website and the withdrawal was only confirmed on the DPD website. The median time to a first safety warning was 1094 days (IQR 551.8, 1812.5) and 778 to withdrawal (IQR 486.5, 1119.5).

Of the 298 NASs approved from 1 January 2000 to 31 March 2012, 79 were biologics (60 with no safety warnings and 19 with safety warnings) and 219 were traditional medications (175 with no safety warnings and 44 with safety warnings). The therapeutic status of 336 NASs was determined from either the PMPRB (296 NASs) or Prescrire (40 NASs) evaluations. Three hundred and five were not significant therapeutic advances (232 with no safety warnings and 73 with safety warnings) and 31 were therapeutic advances (20 with no safety warnings and 11 with safety warnings). Of the 70 NASs where the therapeutic status could not be determined, 66 had no serious safety warnings and 4 had a warning; none were withdrawn from the market.

Twenty-two of the 31 NASs that were therapeutic advances received a priority review, whereas 67 of the 305 NASs that were not significant advances also had a priority review. Overall, the review status was 77.4% accurate in determining the therapeutic rating of the NAS.

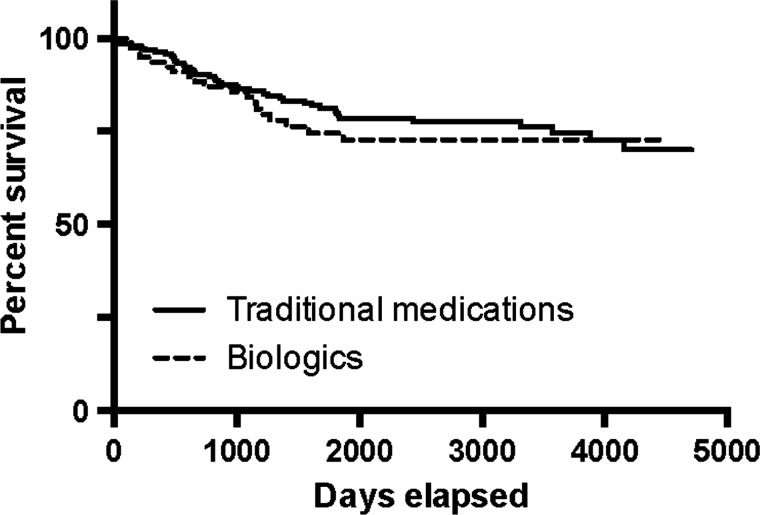

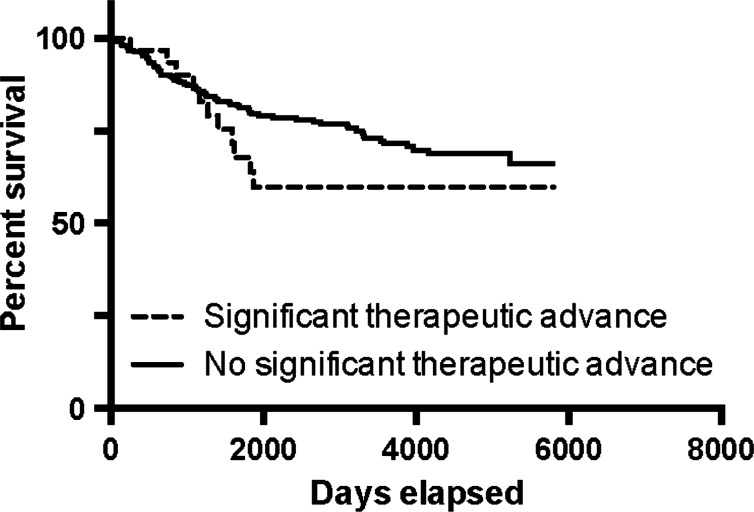

The Kaplan-Meier curves show that the probability of a traditional NAS acquiring a serious safety warning and/or being withdrawn was 29.9% (95% CI 21.8% to 40.2%) vs 27.3% (95% CI 18.2% to 39.7%) for an NAS of biological origin (figure 1, p=0.47, log-rank test). For medications that were significant therapeutic advances the probability was 40.2% (95% CI 24.5% to 60.9%) vs 33.9% (95% CI 26.4% to 42.7%) for those that were not (figure 2, p=0.18, log-rank test).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of new active substance survival: traditional medications versus biologics.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of new active substance survival: significant therapeutic advance versus no significant therapeutic advance.

Discussion

The results of this study support the null hypotheses in both cases of no difference in safety warnings between traditional medications versus biologics and no difference between drugs with significant therapeutic benefits versus those without. However, given the wide CIs, this conclusion should be regarded as tentative. Further research using a larger number of NASs might show statistically significant differences. Other comparisons between groups of drugs that have used safety warnings have similarly found no difference in postmarket safety.14

The finding that there was no difference in the probability of acquiring a postmarket safety warning for NASs regardless of their level of therapeutic benefit is welcome news as it is one indication that more benefits are not being traded off against more harms. At the same time, it also calls into question the benefit : harm ratio of the latter group of drugs as the benefits they offer are significantly lower, whereas the probability that they will acquire a serious safety warning is the same. In this study, 90.8% (305/336) of drugs were of no additional significant therapeutic benefit and fell into this category. Getting drugs with significant benefits to market quickly should be a priority and Health Canada should investigate whether its ability to determine what type of review is most appropriate for an NAS could be improved beyond its current level of 77.4% accuracy. Being better able to determine the eventual therapeutic benefit could mean that more than 71% (22/31) of drugs with significant therapeutic benefits will receive a priority review while at the same time having fewer than 22% (67/305) without significant therapeutic benefits getting the same type of resource intensive review.

Knowing that biologics do not have any greater probability of receiving a serious safety warning compared with traditional medications is also reassuring as biologics now constitute about 25% of all new drugs approved,15 and it is quite likely that drug research and development will be increasingly turning to biologics. This study showed that 27.3% of biologics eventually receive a serious safety warning or have to be withdrawn from the market. This figure is virtually the same as the 29% Kaplan-Meier estimate for a first safety-related regulatory action for biologics approved in the USA and the European Union between January 1995 and June 2008.15

It needs to be noted that the presence or absence of regulatory safety warnings is not equivalent to the overall safety of a product. An evaluation of overall safety would also include an examination of risks detected prior to approval, contraindications and warnings about use of a drug. However, an examination of the time to the first postmarket regulatory warning, the methodology that was used in this paper, is consistent with what other authors have carried out in analysing the postmarket safety profile of drugs in general,16 specific classes of drugs15 and in comparing different groups of drugs.14

This study has several limitations. One possible criticism is that there might be a systematic difference in the frequency of ADR reporting depending on the class of the drug so that, to take one scenario, ADRs might be under-reported for biologics compared to traditional drugs. However, postmarket regulatory action encompasses more than just the receipt and analysis of ADR reports. While safety reports are sometimes triggered by ADRs, Health Canada also utilises other sources of information in making its decision about issuing a serious safety warning.17 The definition of a serious safety warning was based on the way that Health Canada displayed the information (bolded black print and/or boxed text), but the criteria that Health Canada used to develop its safety warnings and the emphasis that it placed on any particular safety issue are not known. There were inconsistencies in the Health Canada databases. Some drugs identified as an NAS in the TPD annual reports were not called an NAS in the NOC Online Query website. Other drugs listed in the annual reports could not be found on the DPD website. On the other hand, the information that gatifloxacin was no longer marketed in Canada was only found on the DPD website. The date on which an NAS receives an NOC is not necessarily the date on which the company actually decides to market the drug, and therefore the length of time the drug is available before it receives a safety warning may be shorter than what is reported here. The therapeutic value of 70 of the NAS could not be determined from the two sources consulted. It is not possible to determine whether there were differences in the number of people who were potentially harmed by the safety problems that triggered the safety warnings for the various drugs. Similarly, all safety warnings were treated as equivalent regardless of the possible number of people affected or potentially affected or the nature of the safety issue, for example, a catastrophic side effect (efalizumab, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy) or a significant contraindication (dolasetron—any therapeutic use under 18 years of age, any postoperative nausea; see online supplementary appendix). Once again though, this approach is consistent with that used by Arnardottir et al,14 Giezen et al15 and Lasser et al.16 Finally, it is important to note that the regulatory decision to issue a safety warning should not be equated with the actual degree of harm caused by the drug.

Although this study relied primarily on Canadian data, its conclusions regarding the postmarket safety profile of the four groups of drugs examined are likely to be generalisable to other countries and regions (eg, Australia, the European Union and the USA) with similar drug regulatory agencies. The distinction between a drug derived from traditional chemical synthesis and a biological product is independent of the regulatory jurisdiction. The method used here to determine the therapeutic value of the products relied on objective evaluations from two groups that did not have any conflicts of interest.

One final question that this study raises is whether the current level of premarket safety evaluation undertaken by Health Canada is acceptable. Depending on the group of drugs being examined, between 27.3% and 40.2% eventually received a serious safety warning or were withdrawn. This is a question that can only be answered through a detailed examination of the way that Health Canada reviews the clinical trial information that it receives from the pharmaceutical companies. At present, Health Canada's treatment of this information as commercially confidential precludes such an examination.18

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Loes Knaapen commented on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: In 2008, JL was an expert witness for the Canadian federal government in its defence against a lawsuit challenging the ban on direct-to-consumer advertising. In 2010, he was an expert witness for a law firm representing the family of a plaintiff who allegedly died from an adverse reaction from a product made by Allergan. He is currently on the Management Board of Healthy Skepticism Inc and is the Chair of the Health Action International—Europe Association Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi: 10.5061/dryad.fg679.

References

- 1.Collier R. Post-market drug surveillance projects developing slowly. CMAJ 2010;182:E43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silversides A. Health Canada's investment in new post-market drug surveillance network a ‘pittance’. CMAJ 2008;179:412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiktorowicz ME, Lexchin J, Moscou K, et al. Keeping an eye on prescription drugs...Keeping Canadians safe: active monitoring systems for drug safety and effectiveness in Canada and internationally. Toronto: Health Council of Canada, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office of the Auditor General of Canada Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the House of Commons. Chapter 4: regulating pharmaceutical drugs—Health Canada Ottawa, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 5.An Act to amend the Food and Drugs Act, Bill C-17 (2013).

- 6.Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA 1998;279:1200–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore TJ, Cohen MR, Furberg CD. QuarterWatch 2011 Quarter 4: FDA direct report rankings as risk index. 2012

- 8.Moore TJ, Cohen MR, Furberg CD. Serious adverse drug events reported to the Food and Drug Administration, 1998–2005. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1752–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lexchin J. Drug withdrawals from the Canadian market for safety reasons, 1963–2004. CMAJ 2005;172:765–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IMS Health Canada Top 50 Prescribed Medications*, 2003. 2004

- 11.Lexchin J. New drugs and safety: what happened to new active substances approved in Canada between 1995 and 2010? Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1680–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Notice of compliance (NOC) database terminology Ottawa: Health Canada, 2010. [cited 9 June 2011]. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/prodpharma/notices-avis/noc-acc/term_noc_acc-eng.php

- 13.Lexchin J. International comparison of assessments of drug innovation. Health Policy 2012;105:221–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnardottir A, Haaijer-Ruskamp F, Straus S, et al. Additional safety risk to exceptionally approved drugs in Europe. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2011;72:490–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giezen TJ, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Straus SMJM, et al. Safety-related regulatory actions for biologicals approved in the United States and the European Union. JAMA 2008;300:1887–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lasser KE, Allen PD, Woolhandler SJ, et al. Timing of new black box warnings and withdrawals for prescription medications. JAMA 2002;287:2215–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MedEffect Canada Health product vigilance framework: Health Canada, 2012. [cited 16 October 2013]. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/pubs/medeff/_fs-if/2012-hpvf-cvps/index-eng.php

- 18.Herder M. Unlocking Health Canada's cache of trade secrets: mandatory disclosure of clinical trial results. CMAJ 2012;184:194–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.