Abstract

Objective

To determine whether analgesic use for painful procedures performed in neonates in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) differs during nights and days and during each of the 6 h period of the day.

Design

Conducted as part of the prospective observational Epidemiology of Painful Procedures in Neonates study which was designed to collect in real time and around-the-clock bedside data on all painful or stressful procedures.

Setting

13 NICUs and paediatric intensive care units in the Paris Region, France.

Participants

All 430 neonates admitted to the participating units during a 6-week period between September 2005 and January 2006.

Data collection

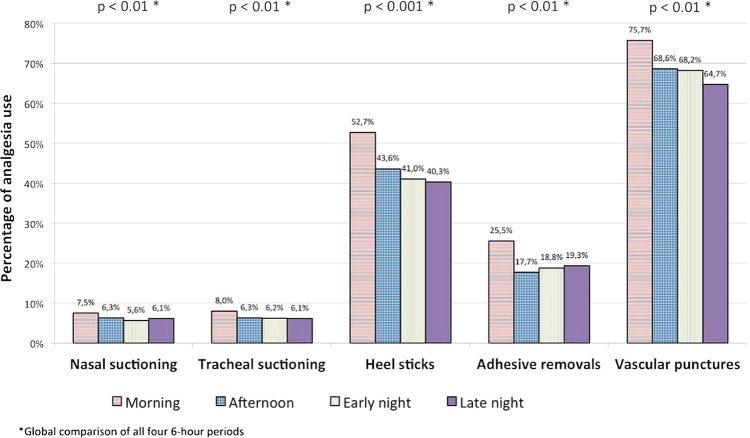

During the first 14 days of admission, data were collected on all painful procedures and analgesic therapy. The five most frequent procedures representing 38 012 of all 42 413 (90%) painful procedures were analysed.

Intervention

Observational study.

Main outcome assessment

We compared the use of specific analgesic for procedures performed during each of the 6 h period of a day: morning (7:00 to 12:59), afternoon, early night and late night and during daytime (morning+afternoon) and night-time (early night+late night).

Results

7724 of 38 012 (20.3%) painful procedures were carried out with a specific analgesic treatment. For morning, afternoon, early night and late night, respectively, the use of analgesic was 25.8%, 18.9%, 18.3% and 18%. The relative reduction of analgesia was 18.3%, p<0.01, between daytime and night-time and 28.8%, p<0.001, between morning and the rest of the day. Parental presence, nurses on 8 h shifts and written protocols for analgesia were associated with a decrease in this difference.

Conclusions

The substantial differences in the use of analgesics around-the-clock may be questioned on quality of care grounds.

Keywords: Pain, Neonate, Neonatology and infant care, After-hours care, painful procedures, pain

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first prospective multicentre study to show variations in analgesic practices around-the-clock.

The around-the-clock variations in analgesic use for procedural pain management did not correspond to an isolated practice of a single centre but rather to the practices of a large geographical region.

Because of the number of centers in the study (13), data about organisational characteristics should be looked on with caution.

Patients and their families expect that the same quality of care be provided to patients 24 h-a-day. In reality, some epidemiological studies, mainly focused on mortality risk and medical errors have found poorer outcomes for hospital care given during evening or night-time hours.1–7 Among neonates, one study reported that perinatal mortality rates fluctuated according to the hour of birth with a peak occurring in the evening3 and another study found a higher mortality for term neonates born in the evenings, nights or weekends.4 These studies raise concern about the homogeneity of care in settings where patients expect safe and high-quality care 24 h-a-day. Significant practice variability also occurs in many other aspects of care. To our knowledge, the variation of neonatal pain management during day and night shifts has not been studied yet.

Neonatal pain management has received much attention during the last two decades, leading professional societies to issue guidelines to improve pain management in this vulnerable population.8 9 These guidelines highlight the necessity to improve analgesia for invasive procedures, which constitute the main source of pain in sick or premature infants admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). However, surveys of clinical practices suggest that many evidence-based interventions have not been applied effectively in NICUs10 and that wide gaps exist between knowledge and practice.11 The undertreatment of pain in this population would be aggravated by variations in analgesic use according to the time of the day. Thus, the question about variation of quality of pain management during the day and night is of practical relevance.

We designed this study to determine whether analgesic use for painful procedures performed in neonates in the NICU and the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) differs during nights and days and during four 6 h periods of the day. This study was conducted as part of the Epidemiology of Painful Procedures in Neonates (EPIPPAIN) study.12

Methods

Study centres

The detailed methodology of the EPIPPAIN study was published elsewhere.12 EPIPPAIN was a prospective observational study designed to collect 24 h a day bedside data on all painful or stressful procedures performed in neonates admitted to NICUs and PICUs of a geographically defined region. All 14 tertiary care centres, NICUs and PICUs in the Paris Region were invited to participate and 13 accepted the invitation.

All the participating units had developed their pain management protocols locally. No instructions were given to modify the standard of care for procedural pain management in neonates.

Study population

We included in this study all neonates admitted to the participating units during a 6-week period between September 2005 and January 2006. Inclusion criterion was admitted preterm neonates younger than 45 postconceptional weeks and term neonates younger than 28 days. There were no exclusion criteria.

Data collection

During the first 14 days of admission to the participating units, prospective data were collected on all neonatal procedures causing pain, stress or discomfort with the corresponding analgesic therapy. Specific preprocedural analgesia included non-pharmacological (eg, sweet solutions, sucking) or pharmacological treatments (eg, single drug or multiple drug doses). Nursing and medical staff at the bedside recorded all procedures on a specific form in real time. Since the EPIPPAIN study did not include data about the characteristics of the participating units, we conducted in March 2010 a phone survey with each head nurse present at the time of the initial study (2005–2006). We enquired about nurse shifts (2 or 3/day), shift rotation (between day and night), existence of a pain coordinator, written standardised protocols for sucrose analgesia, parental presence authorised 24 h a day, ratios of residents to number of beds in order to describe the teaching status13 and existence of a night head nurse.

Painful procedures

The EPIPPAIN study collected data on 430 neonates who underwent 60 969 procedures. Because the current international definition of pain14 does not apply to neonates, we chose a published empirical approach to define pain. This describes pain as an inherent quality of life that appears early in ontogeny to serve as a signalling system for tissue damage.15 Thus, a procedure was considered painful if it invaded the neonate's bodily integrity, causing skin injury or mucosal injury from the introduction or removal of foreign material into the airway or digestive or urinary tract. Of these 60 969 procedures, 42 413 were considered painful, including 44 different procedures. In order to study the differences in analgesic management during the 24 h of the day, we selected the five most frequent procedures that would be readily performed at any time in an intensive care unit and also represent the majority of painful procedures: nasal or tracheal suctioning, heel sticks, adhesive removals and vascular punctures (arterial punctures, venipunctures and intravenous cannulas). As shown in figure 1, these five procedures accounted for 90% of all painful procedures.

Figure 1.

Distribution of painful procedures analysed in the study.

The use of procedural analgesia was defined as the use of specific analgesic given prior to painful procedures (pharmacological or non-pharmacological therapy).

Data analysis

Data were double entered into a relational database (EpiData Entry, V.3·0, Odense, Denmark) and analysed with SPSS, V.14 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA) and Stata V.10 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). Procedures were distributed according to the time when they were performed, into four 6 h periods: morning (from 7:00 to 12:59), afternoon (from 1:00 to 18:59, early night (from 19:00 to 00:59) and late night (from 1:00 to 6:59). We also defined daytime as morning+afternoon and night-time as early night+late night. These timings were chosen because in France, most of the day and night nurse shifts start at 7:00 and 19:00, respectively. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise continuous and categorical variables.

The outcome was the use of procedural analgesia. We calculated the percentage of use of procedural analgesia for each of the 6 h periods, daytime, night-time and for the period including afternoon+early night+late night. Since data were not independent, procedures were clustered by child and centre levels. Therefore, the use of procedural analgesia was compared across periods using a multilevel model with random effect at child and centre levels.

We assessed changes in the effect of time of day across the centres by computing specific centre crude OR to test heterogeneity of the ORs across centres. Then, we constructed a model including procedures and children characteristics that were found to be associated with the use of specific analgesic prior to procedures in the EPIPPAIN study (day of procedure, mechanical ventilation, parental presence, continuous analgesia, surgery sex and gestational age) and variables describing centres (nurse shift, nurse rotation, pain coordinator, written protocols for sucrose analgesia, policy on parental presence authorised 24 h, night head nurse and teaching status). In order to investigate factors associated with differences in analgesic use 24 h a day, we tested the interactions between analgesic use and the characteristics of newborns, centres, and procedures. We used a multilevel logistic regression model with random intercept and random slope in order to test cross-level interactions and to control for confounding factors.16 17 In this multilevel analysis, procedure, child and centre were at the lowest, second and highest level, respectively.

All the described factors were included in our model and all interactions between time of procedures (daytime night-time) and each covariate were obtained. The results are presented as point estimate ORs with two-sided 95% CIs. The threshold for statistical significance was set up at a probability value of <0.05.

Results

From the 430 neonates included in the study, 309 (71.9%) were from NICUs and 121 (28.1%) from PICUs. The mean (SD) length of stay was 8.4 (4.6) calendar days and the observation period represented 3598 patient-days. The overall rate of mechanical tracheal ventilation was 70.5%, but it varied from 46.2% to 92% across the units. Table 1 lists the demographic characteristics of the study population and table 2 lists the characteristics of the participating centres. Online supplementary appendix 1 shows the distribution of painful procedures by hour of the day. Overall, 7724 out of 38 012 (20.3%) painful procedures were carried out with the provision of a specific analgesic treatment. Regarding heel sticks and vascular punctures, 3696/8396 (44.0%) and 1483/2088 (71.0%), respectively, were performed with specific analgesic.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of 430 neonates

| Characteristics | Number (%) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age group at birth (weeks) | ||||

| 24–29 | 119 (27.7) | |||

| 30–32 | 108 (25.1) | |||

| 33–36 | 84 (19.5) | |||

| 37–42 | 119 (27.7) | |||

| Birth weight (g) | 1962 (957) | 1743 (1155–2738) | 490–4760 | |

| Male | 237 (55.1) | |||

| Inborn (born at study hospital) | 237 (55.1) | |||

| Age at admission (h) | 2.5 (0.5–24.0) | |||

| Surgery during the study period | 30 (7.0) | |||

| Mechanical tracheal ventilation | 303 (70.5) | |||

| Duration of participation (days) | 8.4 (4.6) | 8.0 (4.0–14.0) | 1–14 | |

| Overall | 11.6 (3.8) | 14.0 (9.0–14.0) | 2–14 | |

| 24–29 weeks | 8.7 (4.6) | 9.0 (4.0–14.0) | 1–14 | |

| 30–32 weeks | 6.6 (4.0) | 6.0 (3.0–9.0) | 2–14 | |

| 33–36 weeks | 6.0 (3.9) | 5.0 (3.0–8.0) | 1–14 | |

| 37–42 weeks | ||||

| Hospitalised for more than 14 days | 126 (29.3) | |||

| Died during the study period | 24 (5.6) | |||

Table 2.

Characteristics of centres

| Number of centres n=13 |

|

|---|---|

| Nurse shift | |

| 2 per day | 9 |

| 3 per day | 4 |

| Day–night nurse rotation | |

| Yes | 7 |

| No | 6 |

| Pain coordinator | |

| Yes | 10 |

| No | 3 |

| Written standardised protocols for sucrose analgesia | |

| Yes | 11 |

| No | 2 |

| Parental presence authorised 24 hours | |

| Yes | 6 |

| No | 7 |

| Teaching status* | |

| Minor | 6 |

| Major | 7 |

| Night head nurse | |

| Yes | 2 |

| No | 11 |

*Postgraduate trainees/bed ratio: minor teaching units if ratios were one-fourth or less, major teaching units if ratios were higher than one-fourth.

Aiken LH et al.13

Analgesic use according to time of the day

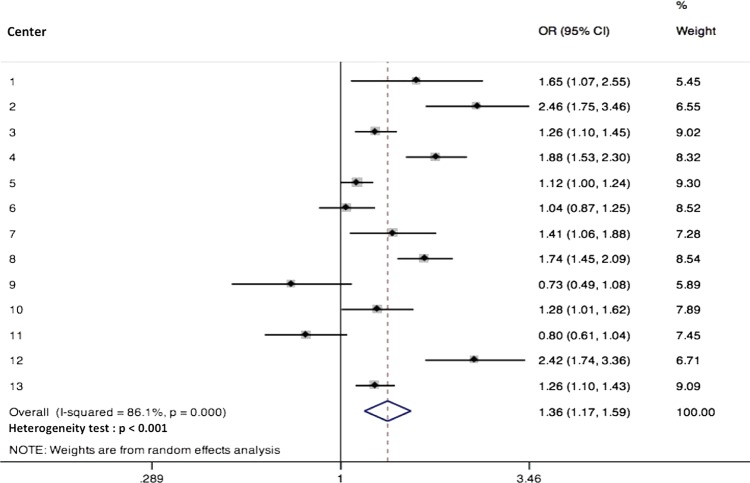

For morning, afternoon, early night and late night, respectively, the use of analgesic was 25.8%, 18.9%, 18.3% and 18% (p<0.001). Figure 2 shows the use of analgesic for each 6 h period of the day by category of procedures. For all painful procedures taken together or for skin-breaking procedures, the use of analgesic was higher in the morning, decreased during the day and was lowest in the late night.

Figure 2.

Use of analgesics during each of the 6 h period of the day by category of procedure.

For all procedures taken together or for skin-breaking procedures analysed separately, the use of analgesic was significantly higher for procedures performed in the morning versus the rest of the day (p<0.001 for all painful procedures, p<0.01 for heel sticks and vascular punctures), as well as for all painful procedures (p<0.01) and heel sticks (p<0.05) performed during daytime versus night-time. Use of analgesic was close to be significantly higher for vascular punctures performed during daytime versus night-time (p=0.07) Table 3.

Table 3.

Differences in use of analgesics for procedures performed in the morning versus the rest of the day and for procedures performed in daytime versus night-time.

| Number of procedures N |

Procedures carried out with specific analgesic |

Relative reduction* | Univariate analysis p Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Per cent | Per cent | |||

| Morning versus rest of the day | |||||

| 5 painful procedures | |||||

| Morning | 9861 | 2546 | 25.8 | ||

| Rest of the day | 28 151 | 5178 | 18.4 | 28.8 | <0.001 |

| Heel sticks | |||||

| Morning | 1860 | 980 | 52.7 | ||

| Rest of the day | 6536 | 2716 | 41.6 | 21.1 | <0.01 |

| Vascular punctures | |||||

| Morning | 955 | 723 | 75.7 | ||

| Rest of the day | 1133 | 760 | 67.1 | 11.4 | <0.01 |

| Daytime versus night-time | |||||

| 5 painful procedures | |||||

| Daytime | 19 059 | 4261 | 22.5 | ||

| Night-time | 18 953 | 3463 | 18.3 | 18.3 | <0.01 |

| Heel stick | |||||

| Daytime | 3871 | 1856 | 47.9 | ||

| Night-time | 4525 | 1840 | 40.7 | 15.2 | <0.05 |

| Vascular punctures | |||||

| Daytime | 1363 | 1003 | 73.6 | ||

| Night-time | 725 | 480 | 66.2 | 10.0 | 0.07 |

*Percentage of relative reduction in the use of specific analgesic.

†These are results from multilevel analysis with time of day as the only explanatory variable. In these multilevel analyses, procedure, child and centre were at the lowest, second and highest level, respectively.

Factors associated with diurnal variations in analgesics

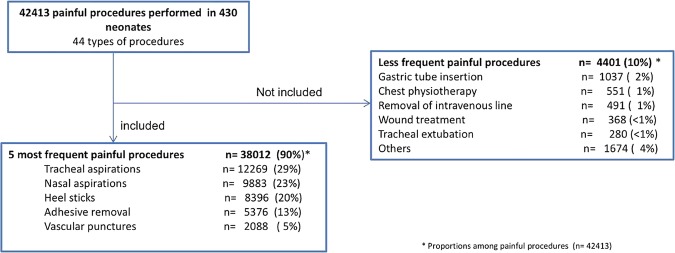

Use of analgesic varied widely among centres (from 4.0% to 49.8%) as shown in online supplementary appendix 2. Moreover, difference in use of analgesic between daytime and night-time significantly varied among centres as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Use of analgesics for procedures performed in daytime versus night-time by centres; test of heterogeneity—p < 0.001.

Interactions between differences in analgesic use during daytime and night-time and the characteristics of children, centres and procedures in univariate analysis are listed in table 4. We can see, for instance, that regarding mechanical ventilation, the relative reduction in analgesic use during night-time compared with daytime was 13.1% in invasively ventilated infants and 20.8% in spontaneously breathing or non-invasively ventilated infants.

Table 4.

Interactions between differences in analgesic use during daytime and night-time and characteristics of children, centres and procedures in univariate analysis

| Factor | Univariate analysis |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedures carried out with specific analgesic |

Daytime compared with night-time: relative reduction* (%) | Daytime compared with night-time: OR | Interaction test (p Value)† | ||||

| Daytime |

Night-time |

||||||

| n/N | % | n/N | % | ||||

| Day of procedure‡ | |||||||

| D1 | 272/1789 | 15.2 | 276/1667 | 16.6 | −8.9 | 0.90 (0.75–1.09) | |

| D2–D14 | 3989/17 164 | 23.2 | 3187/17 392 | 18.3 | 21.2 | 1.35 (1.28–1.42) | <10.3 |

| Mechanical ventilation | |||||||

| Yes | 1668/11 908 | 14.0 | 1501/12 327 | 12.2 | 13.1 | 1.18 (1.09–1.27) | |

| No | 2593/7045 | 36.8 | 1962/6732 | 29.1 | 20.8 | 1.42 (1.32–1.52) | <10.3 |

| Parental presence | |||||||

| Yes | 331/1488 | 22.2 | 131/485 | 27.0 | −21.4 | 0.77 (0.61–0.98) | |

| No | 3930/17 465 | 22.5 | 3332/18 574 | 17.9 | 21.0 | 1.33 (1.26–1.40) | <10.3 |

| Continuous analgesic | |||||||

| Yes | 738/6341 | 11.6 | 722/6864 | 10.8 | 9.6 | 1.12 (1.01–1.25) | |

| No | 3523/12 612 | 27.9 | 2741/12 195 | 22.5 | 19.5 | 1.34 (1.26–1.42) | 0.005 |

| Surgery | |||||||

| Yes | 337/1576 | 21.4 | 300/1714 | 17.5 | 18.2 | 1.28 (1.08–1.53) | |

| No | 3924/17 377 | 22.6 | 3163/17 345 | 18.2 | 19.5 | 1.31 (1.24–1.38) | 0.829 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 2363/10 758 | 22.0 | 1877/10 757 | 17.4 | 20.9 | 1.33 (1.25–1.43) | |

| Female | 1898/8198 | 23.2 | 1586/8302 | 19.1 | 17.6 | 1.28 (1.18–138) | 0.410 |

| Gestational age | |||||||

| ≥37 weeks | 583/3803 | 15.3 | 435/3796 | 11.5 | 25.2 | 1.40 (1.22–1.60) | |

| <37 weeks | 3678/15 150 | 24.3 | 3028/15 263 | 19.8 | 18.3 | 1.30 (1.23–1.37) | 0.295 |

| Nurse shift | |||||||

| 3 per day | 1634/5995 | 27.3 | 1276/5907 | 21.6 | 20.7 | 1.36 (1.25–1.48) | |

| 2 per day | 2627/12 958 | 20.3 | 2187/13 152 | 16.6 | 18.0 | 1.28 (1.20–1.36) | 0.230 |

| Nurse rotation | |||||||

| No | 1853/7507 | 24.7 | 1477/7704 | 19.2 | 22.3 | 1.38 (1.28–1.49) | |

| Yes | 2408/11 446 | 21.0 | 1986/11 355 | 17.5 | 16.9 | 1.26 (1.18–1.34) | 0.068 |

| Pain coordinator | |||||||

| No | 502/2844 | 17.7 | 368/2933 | 12.5 | 28.9 | 1.49 (1.29–1.73) | |

| Yes | 3759/16 109 | 23.3 | 3095/16 126 | 19.2 | 17.8 | 1.28 (1.22–1.35) | 0.053 |

| Written protocols for sucrose analgesia | |||||||

| Yes | 3663/15 325 | 23.9 | 3155/15 508 | 20.3 | 14.9 | 1.23 (1.17–1.30) | |

| No | 598/3628 | 16.5 | 308/3551 | 8.7 | 47.4 | 2.08 (1.80–2.41) | <10-3 |

| Parental presence authorised 24 hours | |||||||

| No | 2510/11 949 | 21.0 | 2091/12 023 | 17.4 | 17.2 | 1.26 (1.18–1.35) | |

| Yes | 1751/7004 | 25.0 | 1372/7036 | 19.5 | 22.0 | 1.28 (1.27–1.49) | 0.102 |

| Night head nurse | |||||||

| No | 2843/12 348 | 23.0 | 2399/12 889 | 18.6 | 19.2 | 1.31 (1.23–1.39) | |

| Yes | 1418/6605 | 21.5 | 1064/6170 | 17.2 | 19.7 | 1.31 (1.20–1.43) | 0.955 |

| Teaching status | |||||||

| Minor | 1798/7222 | 24.9 | 1511/7516 | 20.1 | 19.2 | 1.32 (1.22–1.42) | |

| Major | 2463/11 731 | 21.0 | 1952/11 543 | 16.9 | 19.5 | 1.31 (1.22–1.40) | 0.864 |

*If positive, analgesia was higher during daytime.

†p Value <0.05 indicates that the factor modified the difference in analgesic use between daytime and night-time in univariate.

‡Related to admission.

The inclusion of all clinical factors in a multilevel analysis showed that analgesic use was significantly higher for procedures performed during daytime versus night-time (OR=2.25 (1.10 to 4.60), p<0.05). In this multilevel model, day of procedure (related to admission), mechanical ventilation, parental presence, nurse shift and written protocol for analgesia significantly interacted with time of procedure, as shown in table 5. (The whole list of ORs from the model is shown in online supplementary appendix 3). Presence of parents reversed the difference in use of analgesic between daytime and night-time; that is, analgesic was significantly more frequently used in night-time than in daytime when parents were present.

Table 5.

Significant interactions between differences in analgesic use during daytime and night-time and characteristics of children, centres and procedures in a multivariate, multilevel analysis*

| Factor | Interaction test (p value) | Interaction direction |

OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase difference† | Decrease difference† | |||

| Day of procedure‡ | <0.001 | D2–D14 | 1.56 (1.24–1.95) | |

| Mechanical ventilation | <0.05 | Absence of mechanical ventilation during procedure | 1.20 (1.02–1.43) | |

| Parental presence | <0.001 | Parents present | 0.58 (0.44–0.78) | |

| Nurse shift | <0.01 | 12-hour nurse shifts | 1.42 (1.05–5.55) | |

| Written protocols for sucrose analgesia | <0.001 | Absence of written protocols for sucrose analgesia | 2.44 (1.56–3.70) | |

*This is a multilevel analysis. The exposure was time of procedure (daytime vs night-time). Factors in level 1 (associated with procedure) were day of procedure, mechanical ventilation, parental presence and continuous analgesia. Factors in level 2 (associated with children) were surgery, sex and gestational age. Factors in level 3 (associated with centre) were nurse shift, nurse rotation, pain coordinator, written protocols for sucrose analgesia, parental presence authorised 24 h, night head nurse and teaching status). Interactions between each factor and daytime versus night-time were included in the model. Only factors that significantly interacted with time of procedure are shown in the table.

†Refers to the difference in analgesic use during daytime compared with night-time.

‡Related to admission.

Discussion

This is the first prospective multicentre study to show variations in analgesic practices around-the-clock. The use of specific analgesic for painful procedures was more frequent during daytime than night-time. Moreover, we found a sharp decrease in use of analgesics from morning to afternoon, followed by a gentle decline thereafter.

The relative reduction in the use of specific analgesic between daytime and night-time was 18.3% for all five painful procedures and this difference reached 28.8% between the morning and the rest of the day. Such substantial differences in the use of analgesic may be questioned on quality of care grounds. We consider that the lower use of analgesic during those periods represents a marker of poor quality care that needs to be overcome. The differences in analgesic use between daytime and night-time that we found in this study were independent of the type of procedure and whether the procedure was more frequently performed during a period of the day. In fact, heel sticks were homogeneously distributed around-the-clock and vascular punctures were more frequent during the morning, but the differences in analgesic use were very similar and consistent (see online supplementary appendix 1).

The around-the-clock variations in analgesic use for procedural pain management did not correspond to an isolated practice of a single centre but rather to the practices of a large geographical region. The participation of all but one centre in this region, the uniform data collection at all centres and 100% patient inclusion during the study period ensure that the study cohort was representative of NICU procedural pain management in the Paris region. The extrapolation of these results to the entire French territory may be possible but not totally certain because of conflicting arguments. On the one hand, (1) the Paris region is the most populated region in France and practices within this area closely may reflect those of the country and (2) analgesic use was significantly more frequent during daytime than night-time in 8 of 13 centres, but on the other hand, the analysis of crude OR by centre did not show homogeneity (figure 3).

The variation of quality of neonatal care over the day has been rarely studied directly. Most of the studies have used outcomes as a proxy to assess this variation. Some studies reported increased rates of perinatal death at night.3–5 Although mortality could be considered as an important proxy to assess quality of care, it has the disadvantage of being related to only serious or critical conditions and it is exposed to several confounding factors. Medication error rate has also been used in a few studies to assess variations in quality of care. It has been found that errors were higher during night-time than during daytime.6 18 However, care quality cannot be restricted to a safety problem. Optimal care quality implies, among other standards, care without pain. Thus, analgesic use for painful procedure is also a parameter to measure care quality.

In an attempt to explain our findings, we investigated factors associated with differences of analgesic use around-the-clock. Parental presence, nurses on 8 h shifts and written protocols for analgesia decreased the difference of analgesic use between day and night. These results suggest that written protocols or parental presence may limit the reduction of analgesic use during night-time. Protocols limit the freedom of healthcare providers about the management of pain, making the practice of caregivers more homogeneous. It has been reported that the presence of protocols, by harmonising practices, increases the quality of care.10 Similarly, it has been reported that the presence of parents influences the practice of caregivers.19 Our data also suggest that shorter hour shifts (8 h) for nurses decrease the difference of analgesic use between day and night. In other healthcare areas, it has been shown that 12 h shifts negatively influence the behaviour of care providers yielding to less efficient care.18 20 However, the area of variations in pain management practices is highly complex and to attempt to explain it by staffing or protocols is probably simplistic. Other factors that we have not studied could play a role. Contextual factors may influence staff behaviours. Although the number of nurses is homogeneous during daytime and night-time in French NICUs, more medical staff is present in the morning and in the afternoon. Interprofessional collaboration practices21 and higher access to personnel to care for complex patients22 may enhance pain practices. Thus, analgesic use may also be influenced by the total number of staff and not only nurses.

We acknowledge two limitations of this study. First, a potential bias would be a difference in quality of data collection during days and nights. We consider that this is not likely because we ensured a completeness of reporting by verifying from the patients’ charts that all procedures were documented on the study datasheets. Furthermore, there is no reason that a nurse recorded a procedure but not the use of analgelsia. Second, we collected data about the characteristics and organisation of centre in a retrospective manner 5 years after the collection of clinical data. This might have introduced a bias. However, we feel that this bias was minimised because we obtained data from the head nurse who usually keeps records of all organisational details. Since we only had 13 centres, data about organisational characteristics should be looked on with caution.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the constant efforts to improve care quality should also include standardisation of care across 24 h and pain management guidelines should reinforce this message. The variation of care quality during the day is certainly a complex phenomenon that deserves further research. It appears that human factors intervene in the process of care delivery and we need to better understand them in order to improve care quality. Our results suggest that the modification of organisational factors such as parental presence and written protocols may contribute to the homogenisation of quality of care around-the-clock.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge l'Académie de Médecine.

Footnotes

Contributors: RG participated in the design of study hypothesis, analysed and interpreted the data. He drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. All the authors apart from RG implemented, coordinated and supervised the trial at 1 of 13 participating unit. They reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. RC designed the study and interpreted the data. He reviewed and revised the manuscript, and he approved the final manuscript as submitted. He is the guarantor of this study.

Funding: This study was supported by grant funds from the Fondation CNP, and the Fondation de France, France.

Competing interests: RG received a grant from L'Académie de Médecine to work on this study.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol and the data collection forms were reviewed by the local committee for the protection of human participants. (CPP—Comité de protection des personnes).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Duke GJ, Green JV, Briedis JH. Night-shift discharge from intensive care unit increases the mortality-risk of ICU survivors. Anaesth Intensive Care 2004;32:697–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laupland KB, Shahpori R, Kirkpatrick AW, et al. Hospital mortality among adults admitted to and discharged from intensive care on weekends and evenings. J Crit Care 2008;23:317–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paccaud F, Martin-Béran B, Gutzwiller F. Hour of birth as a prognostic factor for perinatal death. Lancet 1988;1:340–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasupathy D, Wood AM, Pell JP, et al. Time of birth and risk of neonatal death at term: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2010;341:c3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephansson O, Dickman PW, Johansson ALV, et al. Time of birth and risk of intrapartum and early neonatal death. Epidemiology 2003;14:218–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller AD, Piro CC, Rudisill CN, et al. Nighttime and weekend medication error rates in an inpatient pediatric population. Ann Pharmacother 2010;44:1739–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hendey GW, Barth BE, Soliz T. Overnight and postcall errors in medication orders. Acad Emerg Med 2005;12:629–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anand KJ. Consensus statement for the prevention and management of pain in the newborn. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001;155:173–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prevention and management of pain and stress in the neonate. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Committee on Drugs. Section on Anesthesiology. Section on Surgery. Canadian Paediatric Society. Fetus and Newborn Committee. Pediatrics 2000;105:454–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharek PJ, Powers R, Koehn A, et al. Evaluation and development of potentially better practices to improve pain management of neonates. Pediatrics 2006;118(Suppl 2):S78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spence K, Henderson-Smart D. Closing the evidence-practice gap for newborn pain using clinical networks. J Paediatr Child Health 2011;47:92–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carbajal R, Rousset A, Danan C, et al. Epidemiology and treatment of painful procedures in neonates in intensive care units. JAMA 2008;300:60–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, et al. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA 2002;288:1987–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pain terms: a list with definitions and notes on usage. Recommended by the IASP Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain 1979;6:249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anand KJ, Craig KD. New perspectives on the definition of pain. Pain 1996;67:3–6; discussion 209–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merlo J, Chaix B, Ohlsson H, et al. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:290–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merlo J, Chaix B, Yang M, et al. A brief conceptual tutorial on multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: interpreting neighbourhood differences and the effect of neighbourhood characteristics on individual health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:1022–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macias DJ, Hafner J, II, Brillman JC, et al. Effect of time of day and duration into shift on hazardous exposures to biological fluids. Acad Emerg Med 1996;3:605–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnston C, Barrington KJ, Taddio A, et al. Pain in Canadian NICUs: have we improved over the past 12 years? Clin J Pain 2011;27:225–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borges FN, da S, Fischer FM. Twelve-hour night shifts of healthcare workers: a risk to the patients? Chronobiol Int 2003;20:351–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Latimer MA, Johnston CC, Ritchie JA, et al. Factors affecting delivery of evidence-based procedural pain care in hospitalized neonates. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2009;38:182–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevens B, Riahi S, Cardoso R, et al. The influence of context on pain practices in the NICU: perceptions of health care professionals. Qual Health Res 2011;21:757–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.