Abstract

Purpose

Test the hypothesis that in BRAF-mutated melanomas, clinical responses to selumetinib, a MEK inhibitor, will be restricted to tumors in which the PI3K/AKT pathway is not activated.

Experimental Design

We conducted a phase II trial in melanoma patients whose tumors harbored a BRAF mutation. Patients were stratified by phosphorylated-AKT (pAKT) expression (high vs. low) and treated with selumetinib 75 mg po bid. Pretreatment tumors were also analyzed for genetic changes in 230 genes of interest using an exon-capture approach.

Results

The high pAKT cohort was closed after no responses were seen in the first 10 patients. The incidence of low pAKT melanoma tumors was low (approximately 25% of melanomas tested) and this cohort was eventually closed because of poor accrual. However, among the 5 melanoma patients accrued in the low pAKT cohort, there was 1 PR. Two other patients had near PRs before undergoing surgical resection of residual disease (1 patient) or discontinuation of treatment due to toxicity (1 patient). Among the 2 non-responding, low pAKT melanoma patients, co-mutations in MAP2K1, NF1, and/or EGFR were detected.

Conclusions

Tumor regression was seen in 3 of 5 patients with BRAF-mutated, low pAKT melanomas; no responses were seen in the high pAKT cohort.These results provide rationale for co-targeting MEK and PI3K/AKT in patients with BRAF mutant melanoma whose tumors express high pAKT. However, the complexity of genetic changes in melanoma indicates that additional genetic information will be needed for optimal selection of patients likely to respond to MEK inhibitors.

Keywords: phosphorylated AKT, exon-capture, MEK inhibitor, Hedgehog pathway, EGFR mutation

INTRODUCTION

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway transmits activating signals from the cell surface to the nucleus. In approximately 50% of melanomas, there is an activating mutation in BRAF, usually BRAFV600E, that drives cell proliferation(1, 2). Recently, phase II and phase III trials have shown that approximately 50% of patients with BRAF-mutated melanomas respond to RAF inhibitors and that RAF inhibitors prolong overall survival(3-5). In 20% of melanomas, the driver mutation is an activating mutation in NRAS (6). In both BRAF and NRAS-driven melanomas, the MAPK pathway is constitutively activated.

Preclinical studies show that BRAFV600E-mutated melanomas are almost uniformly sensitive to MEK inhibition(7). However, MEK inhibitor treatment of BRAFV600E-mutated melanomas in which there is co-mutation of PTEN and activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway results in G1 arrest but not apoptosis(8). On the other hand, MEK inhibition induces apoptosis in some but not all BRAF-mutated melanomas in which the PI3K/AKT pathway is not mutationally activated. Among NRAS-mutated melanoma cells, sensitivity to MEK inhibition is more variable(7). In contrast, cells in which MEK-ERK signaling is driven by receptor tyrosine kinases are typically insensitive to MEK inhibition(8). These observations led us to the hypothesis that BRAF mutant melanomas with low PI3K/AKT activation would be most sensitive to MEK. This hypothesis is consistent with recent data from cell lines(9) and consistent with the results of a recent phase II trial of selumetinib (AZD6244, ARRY-142886), an allosteric inhibitor of MEK, in unselected melanoma patients. In that trial, 5 of 6 selumetinib responders were found upon retrospective testing to harbor BRAFV600E mutations(10). The PI3K/AKT status of the tumors was not assessed in that trial and in fact, the prevalence of PI3K/AKT activation in melanoma tumors in general is not well-established.

This study, conducted before the availability of BRAF inhibitor therapy, was designed to test the hypothesis that MEK inhibition will induce clinical responses in BRAF-mutated melanomas and that such responses are most likely to be seen in the subset in which the PI3K/AKT pathway is not activated. In this study, we treated patients with BRAF-mutated melanoma stratified on the basis of phosphorylated-AKT (pAKT) expression (high vs. low) as a biomarker for activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway. pAKT expression was used as a marker of pathway activation since a diversity of molecular events can mediate PI3K/AKT activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient eligibility

This was a single institution, phase II trial in which patients with stage IV, or unresectable stage III cutaneous melanoma were eligible if the melanoma harbored a V600E or V600K BRAF mutation. Later in the trial, the protocol was amended to allow NRAS-mutated melanoma.Two cohorts of patients were accrued based on the expression of pAKT (high vs. low) as assessed by immunohistochemistry (see below). If the cohort to which the patient was assigned based on the tumor pAKT expression had been closed to accrual, the patient was considered ineligible for the study. Other eligibility criteria included: ECOG performance status of 0 or 1, measurable disease by RECIST 1.0, at least 4 weeks since any prior chemotherapy and 3 months since prior ipilimumab, adequate hematologic function (WBC ≥3,000/μL, absolute neutrophil count ≥1,500/μL, platelets ≥100,000/μL, hemoglobin ≥9 g/dL not requiring transfusions), adequate liver function (AST/ALT ≤ 2.5 upper limits of normal, bilirubin ≤ 1.5 upper limits of normal), and creatinine ≤ 1.5 mg/dL. Patients were excluded if they had active CNS metastases, uncontrolled serious concomitant medical conditions including HIV, were pregnant or breast feeding, or were unable to take oral medication.

Tumor genotyping

Macrodissection on 5μ-thick unstained sections was conducted using corresponding hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections to ensure greater than 50% tumor nuclei prior to DNA isolation. DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Tissue kit (QIAGEN) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Extracted DNA was quantified on the NanoDrop 8000 (Thermo Scientific).

The study initially restricted enrolment to patients whose tumors harboured a BRAF mutation by Sanger sequencing and/or LNA-PCR/sequencing. Briefly, standard PCR amplification of a 224-bp fragment encompassing the entire coding region of exon 15 of the BRAF gene was performed using the primers BRAF/15F, 5′-TCATAATGCTTGCTCTGATAGG-3′ and BRAF/15R, 5′-GGCCAAAAATTTAATCAGTGG-3′. To increase the sensitivity of the assay, PCR amplification was also performed using standard primers in combination with a 21-mer LNA probe, B-RAF LNA-F: 5′-G+C+T+A+C+A+G+T+G+Aaatctcgatgg/3InvdT/–3′, where the capital letters preceded by the plus (+) sign designate the locked nucleotides. This probe was designed to suppress amplification of the wild-type DNA. The PCR products of both standard and LNA-PCR were purified using Spin Columns (Qiagen) and sequenced using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s protocol on an ABI3730 (48 capillaries) running ABI Prism DNA Sequence Analysis Software.

After October 2010, tumors were genotyped using a Sequenom Mass ARRAY (Sequenom Inc.) assay. Specifically, samples were tested in duplicate using a series of multiplexed assays designed to interrogate the most common BRAF and NRAS mutations. Genomic DNA amplification and single base pair extension steps were conducted using specific primers designed with the Sequenom Assay Designer v3.1 software. The allele-specific single base extension products were then quantitatively analyzed using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight/mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF/MS) on the Sequenom MassArray Spectrometer. All automated system mutation calls were confirmed by manual review of the spectra.

Exon-capture sequencing

We profiled genomic alterations in 230 cancer-associated genes using the IMPACT assay (Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets). This assay utilizes solution phase hybridization-based exon capture and massively parallel DNA sequencing to capture all protein-coding exons and select introns of 230 oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, and members of pathways deemed actionable by targeted therapies. Briefly, barcoded sequence libraries (New England Biolabs, Kapa Biosystems) were subjected to exon capture by hybridization (Nimblegen SeqCap). 93 to 500 ng of genomic DNA was used as input for library construction. Libraries were pooled at equimolar concentrations (100 ng per library) and input to a single exon capture reaction as previously described(11). To prevent off-target hybridization, a pool of blocker oligonucleotides complementary to the full sequences of all barcoded adaptors was spiked in to a final total concentration of 10 μM. DNA was subsequently sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 to generate paired-end 75-bp reads. Sequence data were demultiplexed using CASAVA, and reads were aligned to the reference human genome (hg19) using the Burrows-Wheeler Alignment tool(12). Local realignment and quality score recalibration were performed using the Genome Anlaysis Toolkit (GATK) according to GATK best practices(13). A mean unique sequence coverage of 553X was achieved.

Sequence data were analyzed to identify three classes of somatic alterations: single-nucleotide variants, small insertions/deletions (indels), and copy number alterations. Single-nucleotide variants were identified using muTect (Cibulskis et al., manuscript in preparation) and retained if the variant allele frequency in the tumor was >5 times that in the matched normal. For tumors without matched normal DNA, we filtered out all silent variants and all additional variants present in dbSNP but not in COSMIC (catalog of somatic mutations in cancer)(14). Indels were called using the SomaticIndelDetector tool in GATK. All candidate mutations and indels were reviewed manually using the Integrative Genomics Viewer(15). Mean sequence coverage was calculated using the DepthOfCoverage tool in GATK and was used to compute copy number as described previously(11). Increases and decreases in the coverage ratios (tumor:normal) were used to infer amplifications and deletions, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry

Eligible patients were assigned to either the high pAKT or low pAKT cohort depending on the level of pAKT expression as assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) performed on formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue sections. Immunostained sections were evaluated in a blinded fashion by a dermatopathologist (M.P.) with expertise in cutaneous oncology. Rabbit monoclonal antibody for phosphorylated Akt (Ser473, Cell Signaling Technology; Beverly, MA, USA catalog #3787) was used at a 1:150 dilution. Five μ-thick tissue sections were deparaffinized, pre-treated, and treated by standard methods per manufacturer's instructions.

Biopsies received a numerical score for staining within melanocyte cytoplasm and nuclei. Intensity of expression was characterized as 0 (no staining), 1+ (blush), 2+ (intermediate) or 3+ (intense labeling). For the purpose of this study, cases with 0 or predominantly 1+ staining, with <5% of melanocytes with 2-3+ staining (usually at the tissue edge) were considered low pAkt expressors. Cases showing predominant labeling with 2-3+ intensity were considered to be high pAKT expressors (examples of high pAKT and low pAKT tumors are shown in Supplementary Figure 1).

Treatment plan

Selumetinib was supplied through the NCI Clinical Therapeutics Evaluation Program. Patients were treated with selumetinib 75 mg by mouth twice daily; each cycle was 28 days. All patients signed written informed consent before participating on this study.

Patients were seen by the treating physician at the end of each cycle and repeat radiographic evaluations were performed after every other cycle. For grade III toxicities attributed to selumetinib, drug was held until the toxicity had resolved to grade I and then treatment was resumed at 50 mg/day. If grade III toxicity recurred, the patient was removed from study.

The primary endpoint of the trial was response proportion among the two cohorts as assessed by RECIST 1.0. Since our preclinical data predicted that some BRAF-mutated tumors would undergo G1 arrest rather than apoptosis, we also calculated the fraction of patients in each treatment arm who achieved stable disease lasting at least 4 months. The secondary endpoint was to identify genetic predictors of response to MEK inhibition through analysis of pre-treatment tumor tissue.

Biostatistics

The plan was to accrue 20 patients into each cohort (low vs. high pAKT expression). If at least 4 responses were observed in either cohort, selumetinib would be considered worthy of further testing. If no responses were seen in the first 10 patients, that cohort would be closed to further accrual. With 20 patients per cohort, this would provide 90% power to distinguish a true response rate of 30% from a trivial response rate of 5% in each cohort. This design yields a 95% probability of a negative result if the true response rate is no more than 5%. At the end of the trial, we planned to report the response proportion for each cohort along with a 95% confidence interval.

RESULTS

Between March 31, 2009 and July 11, 2011, 190 melanoma patients were consented and 153 underwent tumor genotyping. Melanomas from 85 patients (55%) were found to have a BRAF mutation; 7 of these were V600K mutations.NRAS mutations were identified in 9 patients (tumors were not screened for NRAS mutations early in the study thus explaining why so few NRAS mutated melanomas were identified). Of patients with a BRAF or NRAS-mutated melanoma, 16 signed consent and were registered to be treated although 1 patient withdrew consent prior to receiving any treatment. In sum, 15 patients were treated on this protocol. All had a BRAFV600E mutation except for 3 patients in the high pAKT cohort who had either a BRAFV600K mutation (2 patients), and one patient whose tumor was characterized as BRAF mutant at the time of screening but on subsequent analysis was shown to harbor a NRASQ61K mutation.The most common reasons for patients who had BRAF mutant tumors not being treated were: the patient was currently receiving other therapy (34%), was found to have high pAKT after that cohort was closed (30%), had brain metastases discovered on pretreatment evaluation (12%), or the tumor had a BRAFV600K mutation before the protocol had been amended to allow entry of patients with V600K mutant tumors (10%). Accrual was rapid when both cohorts (low and high pAKT) were open. However, as noted below, the high pAKT cohort was closed at the interim analysis leaving only the low pAKT cohort open for accrual. Because of the low frequency of low pAKT melanoma tumors, accrual to this cohort was slow. In October 2012, the trial was amended to expand the trial eligibility to include melanoma tumors with BRAFV600K or NRAS mutations.After 5 patients had been accrued to the low pAKT cohort, the trial was closed because of slow accrual.

Patient characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the treated patients according to pAKT expression. Most patients had stage IV, M1c disease (11/15 patients). All but one patient had received prior systemic therapy, most commonly with chemotherapy (12/15 patients). Two patients (both in the high pAKT cohort) had received prior ipilimumab. One patient in each cohort had received prior RAF inhibitor therapy.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| High pAKT | Low pAKT | All patients | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number treated | 10 | 5 | 15 |

| Gender | 9 men:1 woman | 2 men; 3 women | 11 men; 4 women |

| Median age (range) | 60 (22-78) | 70 (55-74) | 68 (22-78) |

| Median ECOG performance status (range) | 0 (0-1) | 1 (0-2) | 0 (0-2) |

| Stage at treatment | |||

| IIIc | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| IVA | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| IVB | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| IVC | 7 | 4 | 11 |

| Pre-treatment LDH levels | |||

| Normal | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Elevated | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Previous systemic treatment | |||

| None | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Chemotherapy | 7 | 5 | 12 |

| Immunotherapy | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Ipilimumab | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| BRAF-directed therapy | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| # of prior therapies/patient | |||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| >3 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

Efficacy

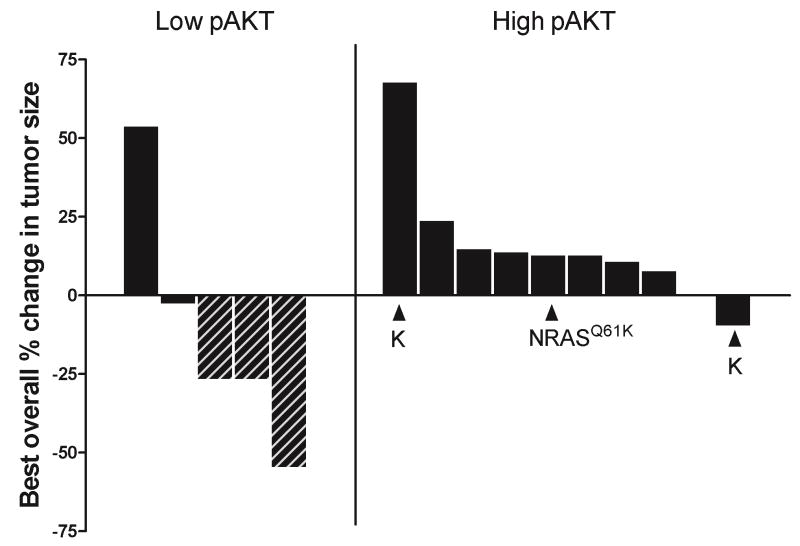

The primary endpoint of this phase II trial was response. Among the 10 patients treated in the high pAKT cohort, there were no anti-tumor responses. Four patients in the high pAKT cohort had stable disease for at least 16 weeks but there were no objective responses by formal RECIST criteria. As a result, the high pAKT cohort was closed at the time of the interim analysis. Five patients were enrolled into the low pAKT cohort before the trial was closed due to slow accrual. Three patients demonstrated tumor regressions although only one fulfilled RECIST criteria for a partial response. Two other patients had near partial response (27% tumor shrinkage in each case). One of these patients had residual disease resected after 30 weeks of selumetinib therapy; the other patient came off study due to toxicity at week 12 requiring discontinuation of selumetinb.Therefore, in the low pAKT cohort, 3/5 patients had either a partial, or near partial response. Figure 1 shows a waterfall plot of best overall response for each patient as a function of treatment arm.

Figure 1.

Waterfall plot showing best overall. Each bar represents an individual patient. The low pAKT cohort is shown on the left; the high pAKT cohort is shown on the right. Hatched bars show patients who experienced tumor shrinkage of at least 25%. All melanomas had a BRAFV600E mutation except for two patients who had melanomas with a BRAFV600K mutation (indicated by K) and one patient who had a melanoma with a NRASQ61K mutation (as indicated).

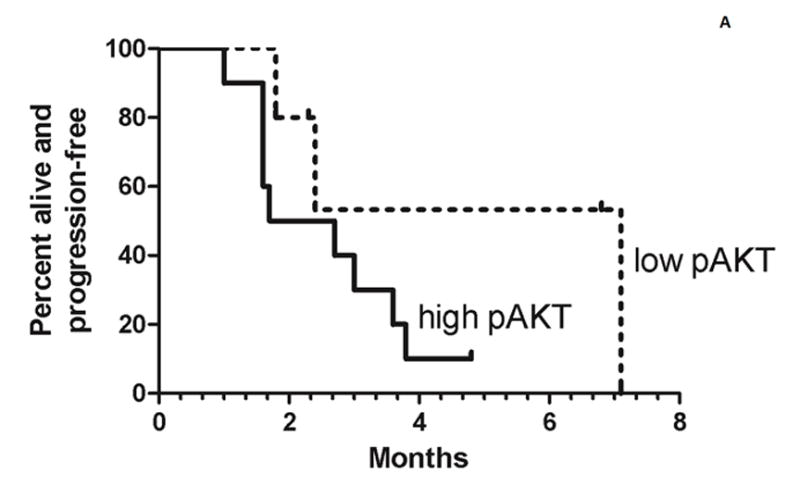

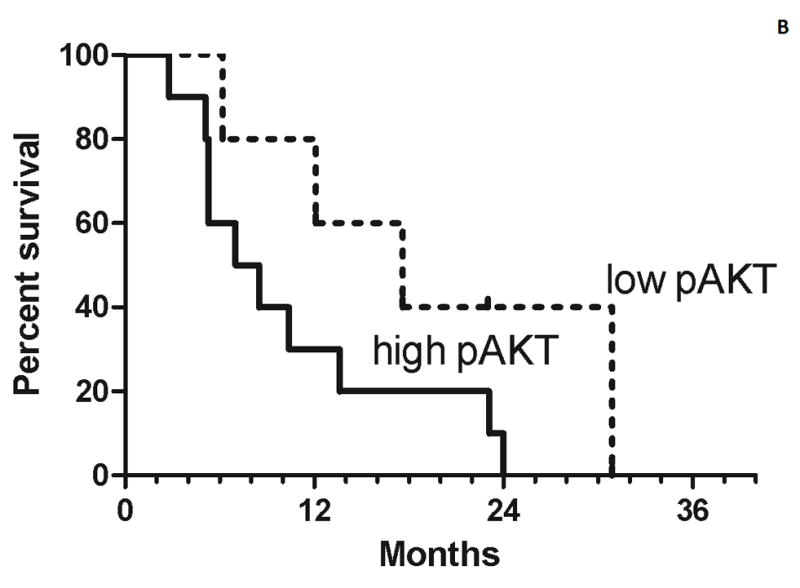

The estimated median progression-free survival was 2.2 months in the high pAKT cohort and 7.1 months in the low pAKT cohort (Figure 2a). The estimated median overall survival of the high pAKT cohort was 8 months and 18 months in the low pAKT cohort (Figure 2b). Although there were too few patients in this study to perform a formal comparison of the two cohorts, the PFS and overall survival curves suggest a better outcome for the low pAKT cohort.

Figure 2.

Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) for both the high pAKT cohort (solid lines) and low pAKT cohort (broken lines). Tick marks indicate censored patients. For the progression-free survival analysis, 3 patients are censored who stopped treatment because of toxicity prior to progression.

Adverse events

The most common adverse events included rash, fatigue, and elevated liver function tests (Table 2). There were few grade III/IV adverse events (rash, elevated liver function tests, lymphopenia, hypoalbuminemia, dyspnea, cardiac function). Three patients required dose reduction due to adverse events. One responding patient in the low pAKT cohort was taken off therapy due to grade III cardiac toxicity.

Table 2.

Adverse events of grade 2 or greater possibly or probably attributable to selumetininb.

| No. of patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

| Acneiform rash | 3 | 2 | |

| ↑ AST | 2 | ||

| ↑ ALT | 2 | 1 | |

| ↑ Alk phosphatase | 2 | 1 | |

| Anemia | 2 | ||

| ↑ glucose | 2 | ||

| Fatigue | 2 | ||

| Diarrhea | 2 | ||

| ↓ lymphocyte count | 3 | ||

| Edema | 2 | ||

| ↓ albumin | 1 | ||

| ↑ bilirubin | 2 | 1 | |

| Dyspnea | 1 | ||

| ↓ phosphate | 1 | ||

| LV dysfunction | 2 | ||

| RV dysfunction | 1 | ||

| Vomiting | 1 | ||

| Valvular heart disease | 1 | ||

| Chest wall pain | 1 | ||

| Heart failure | 1 | ||

| ↓ magnesium | 1 | ||

| Pleural effusion | 1 | ||

Exon capture results

Sufficient tumor-derived DNA was available for next generation sequencing analysis on all 5 patients in the low pAKT cohort and on 2 patients in the high pAKT cohort (Table 3). One of the patients in the high pAKT cohort was found to have a NRASQ61K mutation rather than a BRAF mutation.Mutations were detected in 40 genes among the 5 low pAKT tumor and 32 genes in the 2 high pAKT tumors. Most of the genes were mutated in only a single tumor but 8 genes were found to be mutated in at least 1 tumor in both cohorts: CDKN2A, EPHA6, GRIN2A, MAP2K1, NOTCH2, PTPRD, ARID1A, and PTCH1. Six of 7 tumors showed mutations or deletions in CDKN2A. MITF amplifications were also common (3 patients) (Supplementary Figure 2).

Table 3.

Exon capture sequencing results of 15 patients treated on study.

| Age | Gender | BORR | BRAF | NRAS | PTEN | MEK1 | CDKN2a | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low pAKT cohort | ||||||||

| 70 | M | -27% | V600E | Deleted | NF2 (R187K); RB1 (E79K); PIK3C2G (R1069Q); MITF amp | |||

| 71¶ | F | -55% | V600E/amp | Deleted | Deleted | MITF amp; PTCH1 (P1315L) | ||

| 73 | F | -27% | V600E | G132C | P124S | G101W | PTPRD (D1521A); KIT amp; GRIN2A (G751W) | |

| 75¶ | F | 3% | V600E | R80* | TP53 (P87S); NF1 (S2701F); EGFR (G796S); ARID1A (1334_1335 insQ); PTCH1 (P1315L) | |||

| 23 | M | 54% | V600E | K57N | Deleted | NOTCH2 (P6fs); EPHA6 (G277E); TET1 (A896V) | ||

| High pAKT cohort | ||||||||

| 54 | M | 13% | Q61K | P124S | H83N | EPHA6 (P1055L); NOTCH2 (P2335S); GIN2A (E1202K); GNAQ (TD6S)/deleted | ||

| 69 ¶ | M | 68% | V600K | ERB4 (Q707E/N706fs); CDKN2C amp; MITF amp; ARID1A (Q1363*); PTPRD (E905K); PTCH1 (Q628*); GRIN2A (P985L); MYC amp; DAXX amp | ||||

| 53 | F | 13% | V600E | Insufficient tumor available | ||||

| 59 | M | 11% | V600E | Insufficient tumor available | ||||

| 75 | M | 24% | V600E | Insufficient tumor available | ||||

| 63 | M | 0% | V600E | Insufficient tumor available | ||||

| 63 | M | 13% | V600E | Insufficient tumor available | ||||

| 79 | M | -10% | V600K | Insufficient tumor available | ||||

| 69 | M | 8% | V600E | Insufficient tumor available | ||||

| 53 | M | 14% | V600E | Insufficient tumor available | ||||

Abbreviations: BORR, best overall response as expressed by change in tumor size; amp, amplified.Blank cells indicate wild-type genotypes.

Blank cells indicate wild-type genotypes.

Germline DNA was not available for these patients.

Among the low pAKT cohort, two patients had no response to selumetinib. One of these patients had a mutation in the MAP2K1 gene that encodes for a K57N mutation in helix A of MEK1, a primary downstream effector of BRAF (Supplementary Figure 3). A missense mutation in the amino acid just proximal (Q56P) has previously shown to be highly activating(16). The other non-responding patient in the low pAKT cohort had a variety of genetic changes in the tumor that could have contributed to selumetinib resistance including mutations in NF1 and EGFR. This patient’s tumor also had a PTCH1 mutation which would be predicted to cause activation of the Hedgehog pathway.

Discussion

In this phase II trial, we selected patients with a specific tumor genotype and stratified them based on pAKT expression in the pre-treatment tumor tissue. The trial design was based upon preclinical data suggesting that mutations that activate the PI3K/AKT pathway, including alterations in PTEN, are associated with diminished sensitivity to MEK and BRAF inhibition in BRAF mutant cell lines(9, 17-19).

On the basis of these preclinical studies, we had predicted that significant tumor regression would be seen only in tumors with low pAKT expression and indeed 3/5 patients in the low pAKT cohort had tumor shrinkage of at least 25%, although only 1 formally met RECIST criteria for a partial response. Melanomas with high pAKT were far more common than anticipated (approximately 4:1 incidence) but no RECIST responses were seen in this cohort, although 4 patients had prolonged stable disease on selumetinib.

We obtained detailed genetic data on the tumors in the low pAKT arm using an exon-capture, next generation massively parallel sequencing approach designed to detect mutations, deletions, and amplifications in 230 genes found to be commonly altered in human cancer. In this analysis, mutations/deletions in the MAP2K1, PTEN, CDKN2A, PITCH1, and GRIN2A genes were identified.Among the two patients with low pAKT, BRAF mutant melanomas that exhibited de novo resistance to MEK inhibition, one melanoma had a co-mutation of MEK1 (K57N) which by in silico analysis would be predicted to be highly activating. This finding is notable as a prior report by Emery et al. indicated that mutations in MEK1 including a Q56P mutation in the helix A induced constitutive activation of the kinase and MEK inhibitor resistance(16). The other patient in the low pAKT cohort who did not respond to selumetinib had an alteration upstream of MEK in the MAPK pathway. In particular, this patient’s tumor harbored a EGFRG735S mutation, an activating mutation that can transform NIH3T3 cells(20) and has been found to occur with low frequency in thyroid, lung, and prostate cancers(21-23). This patient’s tumor also showed a truncating mutation in PTCH1, a tumor suppressor gene in the Hedgehog pathway. Notably, 2 of the 5 melanomas in the low pAKT cohort also had a P1315L frameshift mutation in PTCH1(24).Among the patients who demonstrated tumor regression, two were found to have MITF amplifications and the third a MEK1 mutation at proline 124 which has been associated with resistance to vemurafenib (16). It is possible that these genetic changes mitigated the tumor regressions seen in response to selumetinib.

Recently, Patel and colleagues reported their experience in 18 unselected melanoma patients treated with selumetinib(25). They observed 5 clinical responses among the 9 patients with a BRAF-mutated melanoma. No patient with wild-type BRAF responded to the MEK inhibitor. They did not report the AKT activation status of the tumors.

Selumetinib has also been tested clinically in a randomized phase II trial in melanoma patients who were not genotypically pre-selected as a function of BRAF status(10). In that trial, 200 patients were randomized to selumetinib or temozolomide. Six patients randomized to selumetinib had objective PRs; 5 of whom were found retrospectively to harbor a BRAFV600E mutation. There was no difference in progression-free survival between the selumetinib and temozolomide treatment groups, which was the primary endpoint of trial. Somewhat concerning, however, was the observation that overall survival in the selumetinib cohort was inferior to overall survival in the temozolomide cohort despite the fact that cross-over was permitted.These results, along with our current data, suggest that in carefully selected melanoma patients, selumetinib can induce tumor regression and prolong overall survival. In contrast, treating unselected patients will result in a low response rate and may reduce overall survival.

Recently, a more potent MEK inhibitor, trametinib, has undergone phase III testing in melanoma in which study entry was restricted to only patients whose tumors harbored a BRAFV600E/K mutation (26). Trametinib showed a 22% response rate and superior progression-free and overall survival compared to dacarbazine or paclitaxel.This indicates that a potent and selective MEK inhibitor given to a selected (BRAF-mutated) population of melanoma patients can result in improved survival over chemotherapy. Still, only a minority of patients responded to trametinib indicating that additional co-mutational or epigenetic alterations beyond BRAF status also have an impact on MEK inhibitor sensitivity. Another selective MEK inhibitor, MEK162, was also recently shown to induce tumor regressions in a subset of both BRAF-mutated and NRAS-mutated melanomas further highlighting the need to identify additional biomarkers beyond BRAF and NRAS mutational status that predict for MEK dependence (27).

Our data, although preliminary given the small number of patients treated and the failure to fully enroll the low pAKT cohort, suggest that selecting melanoma patients with BRAF-mutated tumors with low expression of pAKT enriches for those sensitive to MEK inhibition.These results support the hypothesis that activation of AKT is associated with resistance to MEK inhibition and provide a rationale for co-targeting the MEK and PI3 kinase/AKT pathways in patients with tumors expressing high levels of phospho-AKT. Our results also suggest that additional mutations within the MAPK and Hedgehog pathways may contribute to resistance to MEK inhibitors. In sum, our data confirm the genetic complexity of melanoma tumors (28) and suggest that detailed genetic information will be needed for optimal therapy selection. We believe these results are especially timely as more potent MEK inhibitors are now available and physicians will need to understand how to select patients who will respond.

Supplementary Material

TRANSLATION RELEVANCE.

MEK inhibitors demonstrate potent anti-tumor effects in preclinical models of BRAF mutant melanoma but induce tumor regression in only a minority of melanoma patients. Pre-clinical data suggest that BRAF mutant melanomas with PI3K/AKT pathway activation are less sensitive to MEK inhibition. This study showed that selumetinib, a selective inhibitor of MEK, induced tumor regression in 3 of 5 patients with BRAF mutant melanomas that had low expression of phosphorylated AKT. No responses were seen in the high phosphorylated AKT group. The results support the hypothesis that activation of AKT is associated with resistance to MEK inhibition and provide a rationale for co-targeting the MEK and PI3 kinase/AKT pathways in patients with tumors expressing high levels of phosphorylated AKT. However, it is likely that additional genetic alterations in the tumor will also need to be considered for optimal selection of MEK inhibitor sensitive melanomas.

Acknowledgments

We thank Efsevia Vakiani, Gopakumar Iyer, and Irina Linkov for technical assistance, Cyrus Hedvat for directing the core facility that performed the BRAF and NRAS typing, and Armando Sanchez and Sherie Mar-Chaim for management of the clinical data.

Funding: This study was funded by the NCI (N01 CM 62206), the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009, and the Starr Cancer Consortium.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: MEL has consulted for Astra-Zeneca, NR serves on the Astra Zeneca Scientific Advisory board, DBS receives research funding from Astra Zeneca for another project.

References

- 1.Davies H, Bignell G, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–54. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, Patel HN, Busam KJ, Kutzner H, et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2135–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, Ribas A, McArthur GA, Sosman JA, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:809–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, et al. Improved Survival with Vemurafenib in Melanoma with BRAF V600E Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sosman JA, Kim KB, Schuchter L, Gonzalez R, Pavlick AC, Weber JS, et al. Survival in BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma treated with vemurafenib. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:707–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jakob JA, Bassett RL, Jr, Ng CS, Curry JL, Joseph RW, Alvarado GC, et al. NRAS mutation status is an independent prognostic factor in metastatic melanoma. Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.26724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joseph EW, Pratilas CA, Poulikakos PI, Tadi M, Wang W, Taylor BS, et al. The RAF inhibitor PLX4032 inhibits ERK signaling and tumor cell proliferation in a V600E BRAF-selective manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14903–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008990107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solit DB, Garraway LA, Pratilas CA, Sawai A, Getz G, Basso A, et al. BRAF mutation predicts sensitivity to MEK inhibition. Nature. 2006;439:358–62. doi: 10.1038/nature04304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gopal YN, Deng W, Woodman SE, Komurov K, Ram P, Smith PD, et al. Basal and treatment-induced activation of AKT mediates resistance to cell death by AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) in Braf-mutant human cutaneous melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8736–47. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkwood JM, Bastholt L, Robert C, Sosman J, Larkin J, Hersey P, et al. Phase II, open-label, randomized trial of the MEK1/2 inhibitor selumetinib as monotherapy versus temozolomide in patients with advanced melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:555–67. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagle N, Berger MF, Davis MJ, Blumenstiel B, Defelice M, Pochanard P, et al. High-throughput detection of actionable genomic alterations in clinical tumor samples by targeted, massively parallel sequencing. Cancer discovery. 2012;2:82–93. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braunschweig AB, Huo F, Mirkin CA. Molecular printing. Nature chemistry. 2009;1:353–8. doi: 10.1038/nchem.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forbes SA, Bindal N, Bamford S, Cole C, Kok CY, Beare D, et al. COSMIC: mining complete cancer genomes in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39:D945–50. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29:24–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emery CM, Vijayendran KG, Zipser MC, Sawyer AM, Niu L, Kim JJ, et al. MEK1 mutations confer resistance to MEK and B-RAF inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20411–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905833106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sosman J, Pavlick A, Schuchter L, Lewis KD, Mcarthur GA, Cowey CL, et al. PTEN immunohistochemical expression as part of the correlative analysis in the BRIM-2 trial. ASCO Annual Meeting; 2011; Chicago, IL. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nathanson KL, Martin AM, Letrero R, D'Andrea K, O'Day S, Infante JR, et al. Tumor genetic analysis of patients with metastatic melanoma treated with the BRAF inhibitor GSK2118436. ASCO Annual Meeting; 2011; Chicago, IL. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xing F, Persaud Y, Pratilas CA, Taylor BS, Janakiraman M, She QB, et al. Concurrent loss of the PTEN and RB1 tumor suppressors attenuates RAF dependence in melanomas harboring (V600E)BRAF. Oncogene. 2011 doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai CQ, Peng Y, Buckley MT, Wei J, Chen F, Liebes L, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation in prostate cancer by three novel missense mutations. Oncogene. 2008;27:3201–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsao M-S, Sakurada A, Cutz J-C, Zhu C-Q, Kamel-Reid S, Squire J, et al. Erlotinib in Lung Cancer — Molecular and Clinical Predictors of Outcome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:133–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murugan A, Dong J, Xie J, Xing M. Uncommon GNAQ , MMP8 , AKT3 , EGFR , and PIK3R1 Mutations in Thyroid Cancers. Endocrine Pathology. 2011;22:97–102. doi: 10.1007/s12022-011-9155-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Douglas DA, Zhong H, Ro JY, Oddoux C, Berger AD, Pincus MR, et al. Novel mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor in localized prostate cancer. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 2006;11:2518–25. doi: 10.2741/1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pastorino L, Cusano R, Nasti S, Faravelli F, Forzano F, Baldo C, et al. Molecular characterization of Italian nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:322–3. doi: 10.1002/humu.9317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel SP, Lazar AJ, Papadopoulos NE, Liu P, Infante JR, Glass MR, et al. Clinical responses to selumetinib (AZD6244; ARRY-142886)-based combination therapy stratified by gene mutations in patients with metastatic melanoma. Cancer. 2012:n/a–n/a. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A, Gonzalez R, Kefford RF, Sosman J, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK Inhibition in Melanoma with BRAF V600 Mutations. N Engl J Med. 2012 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ascierto PA, Berking C, Agarwala S, Schadendorf D, Van Herpen C, Queirolo P, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral MEK162 in patients with locally advanced and unresectable or metastastic cutaneous melanoma harboring BRAFV600 or NRAS mutations. ASCO Annual Meeting; 2012; Chicago, IL. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodis E, Watson IR, Kryukov GV, Arold ST, Imielinski M, Theurillat JP, et al. A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell. 2012;150:251–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.