Abstract

Stimulation of the posterior hypothalamic area (PH) produces antinociception in rats and humans, but the precise mechanisms are unknown. The PH forms anatomical connections with the parabrachial area, which contains the pontine A7 catecholamine cell group, a group of spinally projecting noradrenergic neurons known to produce antinociception in the dorsal horn. The aim of the present study was to determine whether PH-induced antinociception is mediated in part through connections with the A7 cell group in female Sprague-Dawley rats, as measured by the tail flick and foot withdrawal latency. Stimulation of the PH with the cholinergic agonist carbachol (125 nmol) produced antinociception that was blocked by pretreatment with atropine sulfate. Intrathecal injection of the α2-adrenoceptor antagonist yohimbine reversed PH-induced antinociception, but the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist WB4101 facilitated antinociception. Intrathecal injection of normal saline had no effect. In a separate experiment, cobalt chloride, which reversibly arrests synaptic activity, was microinjected into the A7 cell group and blocked PH-induced antinociception. These findings provide evidence that the PH modulates nociception in part through connections with the A7 catecholamine cell group through opposing effects. Antinociception occurs from actions at α2-adrenoceptors in the dorsal horn, while concurrent hyperalgesia occurs from actions of norepinephrine at α1-adrenoceptors. This hyperalgesic response likely attenuates antinociception from PH stimulation.

1. Introduction

The posterior hypothalamic area (PH) has been shown to modulate nociception in both animal and clinical studies. In rat, electrical stimulation of the PH produces potent antinociception (Rhodes and Liebeskind, 1978) and chemical stimulation reduces facial pain in rats (Bartsch et al. 2004). Increases in c-fos positive (activated) cells in the PH are seen after administration of an electrical pain stimulus (Gavrilov et al., 2008) and destruction or deactivation of the PH increases pain responses (Millan et al., 1983; Manning and Franklin, 1998). MicroPET studies show PH activation and neuroplastic changes involving latent pain sensitization following surgery (Romero et al., 2011) and after application of a heat stimulus to an inflamed paw (Hess et al., 2007). Clinical stimulation of the PH has been done effectively for debilitating neurovascular cluster headaches, (Goadsby, 2007; Bartsch et al, 2008; May, 2008; Brittain et al., 2009; Jurgens et al., 2009; Leone and Bussone, 2009; Leone et al., 2010), intractable short lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache with conjunctival tearing,(Bartsch et al., 2011; Leone et al., 2005), chronic paroxysmal hemicranias (Walcott et al., 2009), and refractory paroxysmal pain for trigeminal neuralgia (Cordella et al., 2009). While these studies support the notion that the PH is involved in the descending modulation of nociception, they do not indicate the mechanisms of this involvement.

Recently, we reported that stimulating the PH with the cholinergic agonist carbamylcholine chloride (carbachol) significantly decreases neuropathic pain from constriction of the sciatic nerve, in part through mediation by orexin receptors in the spinal cord dorsal horn (Jeong and Holden, 2009). In other studies, we reported that stimulating the lateral hypothalamus with carbachol produces antinociception mediated in part by α2-adrenoceptors and facilitated by α1 adrenoceptors in a rat model of acute nociception (Holden and Naleway, 2001), via connections with the spinally-projecting A7 catecholamine cell group in the pons (Holden et al., 2002). During these experiments we observed that inadvertent placement of the microinjector in the PH also produced antinociception and that alpha-adrenoceptors in the dorsal horn may have been involved. This observation coupled with the observations of our orexin study led us to further investigate the mechanisms of PH-induced nociceptive modulation.

The involvement of the A7 catecholamine cell group in descending nociceptive modulation has been well documented over several decades. In Sprague-Dawley derived rats from Sasco (West et al., 1993), the A7 cell group is the major source of noradrenergic innervation to laminae I-IV in the dorsal horn (Clark and Proudfit, 1991; Proudfit, 1992). Laminae I-IV are the terminal field of primary afferent nociceptors and contain second order spinothalamic tract neurons (Light, 1992). Synaptic terminals that contain dopamine-β-hydroxylase appear to form synapses both with identified spinothalamic tract neurons (Westlund et al., 1990), and with unidentified dorsal horn neurons (Hagihira et al., 1990; Doyle and Maxwell, 1991a; Doyle and Maxwell, 1991b). Behavioral studies have shown that stimulating the A7 area using electrical or chemical applications produces nociceptive modulation (Yeomans et al., 1992; Yeomans, 1992; Holden et al., 1999; Nuseir et al., 1999; Nuseir and Proudfit, 2000; Holden and Naleway, 2001; Min et al., 2008; Bajic and Commons, 2010; Min et al., 2010).

While tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive neurons have been labeled in the PH, there is no evidence that these neurons are spinally-projecting noradrenergic neurons (Abrahamson and Moore, 2001), and it has been documented that the A5, A6 and A7 areas provide the only source of noradrenergic innervation to the spinal cord (Westlund et al., 1981; Westlund et al., 1983; Bruinstroop et al., 2011). However, the PH does send axonal projections to the parabrachial area, including the A7 area, in monkey (Veazey et al., 1982) and in rat (Vertes and Crane, 1996). In rat, the connection appears to be reciprocal (Cavdar et al., 2001). These findings support the hypothesis that stimulating the PH produces antinociception in part by recruiting the A7 cell group.

To test this hypothesis, three experiments were conducted. In the first experiment, either carbachol or normal saline was microinjected into the PH of rats and nociceptive testing was done using the tail flick and foot withdrawal latency tests. To determine whether PH-induced antinociception is mediated by α-adrenoceptors in the spinal cord dorsal horn, in the second experiment the PH was stimulated to obtain antinociception and then intrathecal (IT) injection of α-adrenoceptor antagonists were given. In the final experiment, the PH was stimulated and then cobalt chloride was microinjected into the A7 area to block synaptic activity. Taken together, these experiments provide behavioral evidence that PH-induced antinociception is mediated in part by the A7 cell group noradrenergic input to the spinal cord dorsal horn. A preliminary account of these results has been published as an abstract (Jeong and Holden, 2005).

2. Experimental Procedures

The Institutional Animal Care Committees at the University of Illinois at Chicago and the University of Michigan approved the experimental protocols used in this study. The experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 80–23, revised 1996). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering, reduce the numbers of animals used, and use alternatives to in vivo experiments.

Animals

Female Sprague-Dawley rats (250–350 g; Charles River, Portage, MI) were used in this study because our previous work was done in females. All rats were maintained on a 12-hour day/night schedule with free access to food and water. To reduce the possibility of estrous cycle influence, rats were randomly assigned to either experimental or control groups and no two rats were taken from the same cage on the same day. Seventy one rats were used for the study as reported, and each rat was used only once.

Analgesiometric testing procedures

To determine the effect of PH stimulation on thermal nociception, the tail flick and foot withdrawal tests were used. In these procedures, a focused beam of high intensity light from a suspended 250-W projection bulb was directed at the dorsal surface of the tail and the hairy surface of the hind feet. The distance from the light to the platform the rats lay on was maintained at 5 cm for all experiments. The tail and paws were blackened with India ink to facilitate even heating of the skin surface. The time interval between the onset of skin heating and the withdrawal response was measured electronically. In the absence of a response, skin heating was terminated after 8 sec to prevent burning. Three response latencies were measured in succession at three places on the tail. The average of the three tail latency values was defined as the nociceptive response latency. For the foot withdrawal, response latencies were measured at one place on the hairy surface of each hind foot. Baseline response latencies of the paws and tail were approximately 2–3 s, as used in previous studies.

Experiment 1: Carbachol or saline microinjection in the PH

Each rat was lightly anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital 35 mg/kg, IP, and the scalp was infused with the local anesthetic bupivacaine (0.25%; 0.10 ml). Supplemental doses of pentobarbital were given during the procedure if the rats vocalized or moved without stimulation, but were rarely required. Immediately after anesthesia, the midline scalp was shaved and the rats were immobilized in a stereotactic apparatus. Using aseptic technique, a 2-cm incision was made, and the muscle and fascia retracted. A 23-gauge stainless steel guide cannula was lowered through a burr hole into the region of the left PH defined by the following stereotactic coordinates: AP −3.1 mm from bregma, lateral −0.5 mm, vertical +2.1 mm, incisor bar set at −2.5 mm. A 30-gauge stainless steel injection cannula was connected to a 10 μl syringe by a length of PE-10 polyethylene tubing filled with either saline or a solution of carbachol 125 nmol in normal saline injected in a volume of 0.5 μl (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO; All solutions were made fresh daily and filtered through a 0.2 μm syringe prior to use.). The injection cannula was then inserted and extended approximately 3 mm beyond the end of the guide cannula. After a baseline response latency measurement was taken and recorded, either saline or carbachol was injected into the PH over a 1-min period using an electronic syringe pump. The injection cannula was left in place for an additional 60 s following completion of the microinjection to reduce flow of drug up the guide cannula. Response latencies were then measured at 5 min intervals until a return to baseline or for 45 min. A separate group of rats was prepared as above, but the PH was pretreated with the cholinergic antagonist atropine sulfate (5 μg/0.5 μl NS) microinjected over 1 min. Carbachol (125 nmol) was then injected and tail flick and foot withdrawal latencies were measured.

Experiment 2: Carbachol microinjection in the PH followed by microinjection of IT α-adrenergic antagonists

Female Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River; 250–350 g) were randomly assigned to groups and prepared for microinjection in the PH as previously described. In addition, an intrathecal catheter constructed from PE-10 polyethylene tubing was inserted through an incision in the cisterna magna and the tip positioned near the lumbar enlargement. The drugs were dissolved in physiological saline and filtered through a 0.2-μm filter immediately before injection. All drugs were injected in a volume of 30 μl using an electronic syringe pump at a rate of 30 μl/min. Carbachol (125 nmol in a volume of 0.05μl) was microinjected into the PH and tail and foot withdrawal response latencies determined at 1, 5, and 10 min post injection. One of the following drugs was then injected intrathecally: The α2-adrenoceptor antagonist yohimbine, the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist WB4101 (97 nmol each, Sigma Chemical Co., or normal saline for control. Tail and foot withdrawal response latencies were measured at 1 min post injection and then every five minutes for 45 minutes. Additional groups of rats received intrathecal injections of one of the antagonists, as described, but without prior PH stimulation.

Experiment 3: Carbachol microinjection in the PH followed by microinjection of cobalt chloride or normal saline in the A7 area

In the third experiment, rats were prepared for PH cannulation as previously described. In addition, a second guide cannula was lowered into the A7 area at the following coordinates: AP +0.6 mm from the interaural line, lateral 2.1 mm, vertical +2.2 mm, incisor bar set at −2.5 mm. After a baseline response latency, carbachol (125 nmol) was microinjected into the PH in a volume of 0.5 μl and response latencies were measured at 1, 5, 10, and 15 minutes. Twenty min after carbachol injection, cobalt chloride (100 mM/0.5 μl) or saline was microinjected in the A7 area using an electronic syringe pump in the manner described above and response latencies measured at 1 min, and then every 5 min for 45 min. Additional controls were done in which saline or cobalt chloride, at doses described previously, was injected near the A7 area in the absence of PH stimulation.

Histology

Following testing, animals were overdosed with sodium pentobarbital and decapitated. The brains were taken and drop fixed in a solution of 10% neutral-buffered formalin. To determine the position of the microinjection sites relative to the PH and the A7 area, 40- m transverse brain sections were cut from blocks of tissue that contained the visible injection cannula tract using a cryostat microtome. The sections were rinsed in cold phosphate-buffered saline PBS, (10 mM), mounted on gel-coated slides, stained with 0.05% neutral red, dehydrated through a series of alcohols and xylenes, and cover slipped. The placement of the microinjection cannula was determined by locating the most ventral position of the cannula tip in serial sections by brightfield microscopy. Tracings of the appropriate sections were then made using the Neurolucida imaging system (Microbrightfield, Colchester, VT). The tracings were compared with drawings from the atlas of Paxinos and Watson to verify that the cannula was within the PH or the A7 cell group (Paxinos, Watson, 2009).

Statistical analysis

Treatment groups consisted of between 6 and 13 rats. Tail and foot withdrawal response latencies are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. Statistical comparisons among treatment groups across multiple time points were made using two-way repeated measures ANOVA, and comparisons among means at specific time points were made using the Holm-Sidak test for multiple post-hoc comparisons. Student’s t-test was used to compare withdrawal latencies for left and right paws. Foot withdrawal latencies were not significantly different between left and right paws for any experiment, so response latencies were averaged for clarity.

3. Results

Portions of data collected for these experiments were done in laboratories at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) and at the University of Michigan (UM). To determine whether there were significant effects of location or time, we compared tail and foot withdrawal latencies from rats done at UIC with those done at UM. Of the groups done in Experiments 1 and 2, only two differences were found. In Experiment 1, there was a statistically significant difference between UIC and UM rats for carbachol injection in the PH for tail flick latency only (4.23 ± 0.16 vs 5.06 ± 0.24 sec; p = 0.005; Student’s T-test). There was no significant difference for foot withdrawal latencies. In Experiment 2, only rats receiving IT yohimbine showed differences. For the tail flick latency, UIC rats had an average latency of 2.99 sec vs 3.40 sec for UM rats (Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test, p = 0.002). For the foot withdrawal test, UIC rats averaged 2.30 ± 0.09 sec vs. 3.13 ± 0.09 sec (p < 0.001; Student’s T-test). There were no significant differences found for the other Experiment 2 groups. All of Experiment 3 was done at UM. We determined that discarding data from rats done at UIC based on clinically insignificant differences comprising fractions of a second would go contrary to principles of ethical animal usage, so data collected from both laboratories were included in the analysis.

Effect of carbachol microinjection in the PH on nociception

Microinjection of carbachol in the PH at sites shown in Fig. 1 produced antinociception on the tail flick test compared to baseline response latencies. Comparisons among the groups showed a significant effect of carbachol compared to normal saline (two way repeated measures ANOVA, F = 6.65(2, 153); p = 0.007) that was dependent on time, as evidenced by a significant interaction effect (p = 0.001). Post hoc comparisons showed significant differences between the two groups from 1 min through 25 min post carbachol injection (4.51 ± 0.25 vs. 3.23 ± 0.25 min; carbachol vs saline). Pretreatment of the PH with atropine significantly reduced the effect of carbachol microinjection at 1, 15, 20, and 25 min after injection (3.80 ± 0.22; atropine; Fig 2A).

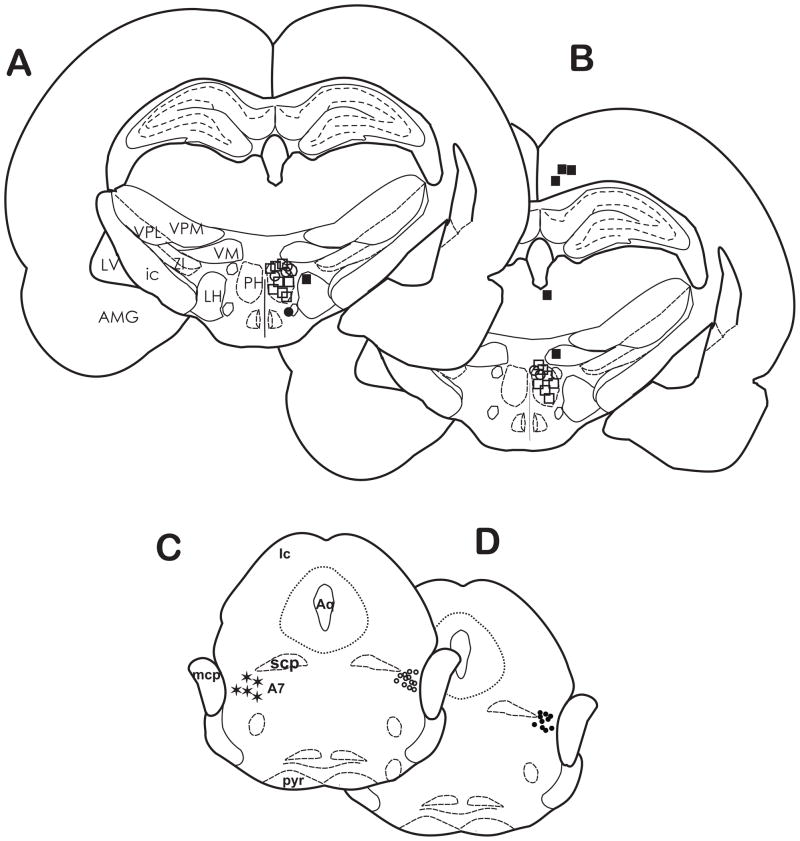

Fig. 1.

The location of carbachol microinjection sites in the PH for tail response latencies in Experiment 1. Most of the injection sites were located within the border of the PH between AP −3.60 and −3.80 mm from bregma. The symbols represent the values of the differences between baseline tail response latencies and those at 15 min after microinjection of carbachol (125 nmol) as follows: (△) 2–3.9 sec; (△) 4–5.9 sec; (□) 6–8 sec. Injection sites located in the lateral hypothalamus (●) and the hippocampus (●) elicited antinociceptive responses and were excluded from data analysis. AMG, amygdala; ic, internal capsule; LH, lateral hypothalamus; LV, lateral ventricle; PH, posterior hypothalamus; VM, ventromedial thalamic nucleus; VPL, ventral posterolateral thalamic nucleus; VPM; ventral posteromedial thalamic nucleus; ZI, zona incerta.

Fig. 2.

Microinjection of carbachol in the PH produced time-dependent increases in nociceptive tail response latencies. Following a baseline response latency measurement, normal saline or carbachol (125 nmol) was microinjected into the PH at time 0. Time-course changes in (A) tail response latencies or (B) foot withdrawal latencies produced by microinjection of saline (□; n = 6) or carbachol (○; n = 6). In a separate group of rats (◇; n = 9), pretreatment with atropine in the PH reduced tail flick latencies and blocked foot withdrawal latencies following carbachol microinjection. Mean response latencies ± SEM. *p< 0.05, carbachol vs saline; #p < 0.05, carbachol vs. atropine.

For the foot withdrawal test, similar results were found. Microinjection of carbachol produced a significant increase in withdrawal latencies (F =98.41 (2,152); p < 0.001) that was dependent on time (interaction effect, p < 0.001). Post hoc tests showed a significant antinociceptive effect following carbachol microinjection compared to control rats (4.73 ± 0.22 vs. 2.31 ± 0.22; carbachol vs. saline, resp.) across all time points, but the results of the 45 min time point must be interpreted with caution, due to the higher baseline of the carbachol group (Fig. 2B). Atropine pretreatment blocked the antinociceptive effect of carbachol across the testing period (2.83 ± 0.19; p < 0.05).

Carbachol-induced antinociception: Effect of IT injections of α-adrenoceptor antagonists

Following microinjection of carbachol in the PH at sites similar to those in Fig. 1, IT injection of α-adrenoceptor antagonists significantly altered tail response latencies (two way RM ANOVA, F = 7.54(2,207); p = 0.003). As can be seen in Fig. 3A, IT injection of the α2-adrenoceptor antagonist yohimbine blocked carbachol-induced antinociception (3.35 ± 0.36 vs 4.43 ± 0.38 sec normal saline; p < 0.05). Conversely, IT injection of the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist WB4101 increased withdrawal latencies, or facilitated antinociception (5.32 ± 0.36, p < 0.05; Fig. 3A). Intrathecal injection of normal saline had no effect on carbachol-induced antinociception. There was a significant interaction effect (p = 0.035), demonstrating that the effect of the antagonists was based on time.

Fig. 3.

Antinociception from microinjection of carbachol (125 nmol) in the PH was blocked by intrathecal injection of the α2-adrenoceptor antagonist yohimbine, but facilitated by injection of the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist WB4101. (A) Carbachol (Carb) was injected at -17 min and three post drug tail response measurements were made at -15, -10 and -5 min. Either Yohimbine (YOH, □, n = 10), WB4101, (○, n = 9) or saline (◆, n = 7) was injected intrathecally at time -1. (B) Time course of the effects of intrathecal injection of either YOH, WB4101, or saline following carbachol microinjection in the PH on foot withdrawal response latencies. Mean response latencies ± SEM. * p < 0.05.

As with tail response latencies, IT injection of α-antagonists significantly altered foot withdrawal latencies following carbachol microinjection in the PH (two way RM ANOVA, F = 20.21(2,207); p < 0.001). Injection of yohimbine blocked carbachol-induced antinociception, and injection of WB4101 increased response latencies (2.78 ± 0.22 vs. 4.76 ± 0.22 vs. 3.69 ± 0.23 sec, yohimbine, WB4101 and saline resp. p < 0.05; Fig. 3B), which were dependent on time (interaction effect (p < 0.001). The greatest effect of yohimbine was seen at 5, 10, and 15 min post antagonist injection, and the strongest effect of WB4101 was seen at 5 and 10 min after antagonist administration.

Intrathecal α-adrenoceptor antagonists given in the absence of carbachol microinjection in the PH produced tail and foot withdrawal response latencies that were not significantly different from normal saline for control (not shown; p > 0.05). This finding indicates that the connection from the PH to the dorsal horn was not tonically active.

Effect of cobalt chloride in the A7 area on carbachol-induced PH antinociception

The third experiment tested whether blockade of synaptic activity in the A7 area would also block carbachol-induced antinociception. Figure 4 shows the approximate locations of carbachol microinjections made in the PH, and of cobalt chloride or normal saline in the A7 area.

Fig. 4.

The location of microinjection sites in the PH and A7 cell group for tail response latencies in Experiment 3. Most of the injection sites for carbachol/cobalt chloride (A) and carbachol/saline (B) were located within the PH between AP −3.60 and −4.16 from bregma at 10 min post carbachol injection. The symbols represent the values of the differences between baseline tail response latencies and those at 15 min after microinjection of carbachol (125 nmol) as follows: (△) 2–3.9 sec; (○) 4–5.9 sec; (□) 6–8 sec. Injection sites located in the cortex, dorsal thalamus, zona incerta (■) and ventral hypothalamus (●) elicited antinociceptive responses and data were excluded from analysis. Microinjections of cobalt chloride (C; ○) and saline (D; ●) were located in the A7 area (✶) approximately AP −8.72 – 10.04 from bregma. A7, A7 catecholamine cell group; Aq, Aqueduct of Sylvius; AMG, amygdala; Ic, inferior colliculus ic, internal capsule; LH, lateral hypothalamus; LV, lateral ventricle; MCP, middle cerebellar peduncle; PH, posterior hypothalamus; pyr, pyramids; SCP, superior cerebellar peduncle;VM, ventromedial thalamic nucleus; VPL, ventral posterolateral thalamic nucleus; VPM; ventral posteromedial thalamic nucleus; ZI, zona incerta.

PH-induced antinociception was blocked by microinjection of cobalt chloride into the A7 area as compared to saline controls for tail response latencies (two way RM ANOVA, F = 18.38(1,171), p < 0.001; Fig. 5A). Cobalt chloride blocked the effect of carbachol in the PH immediately compared to control (3.45 ± 0.37 vs. 5.73 ± 3.7 sec. resp.) and the effect was not based on time (interaction effect = NS). Interestingly, the baselines of both groups were somewhat higher than for previous experiments, but microinjection of cobalt chloride reduced latencies well below baseline levels (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Antinociception produced by microinjection of carbachol in the PH was blocked by microinjection of cobalt chloride in the A7 area. (A) Following a baseline measurement at -25 min, carbachol (Carb) was microinjected in the PH and four tail response latencies were measured. Either cobalt chloride (○; CoCl; n = 11) or saline (●; n = 13) was microinjected in the A7 area. Cobalt chloride significantly reduced tail flick latencies across all time points compared to saline controls (p < 0.05). Mean latency values ± SEM are plotted on ordinate as a function of time (min). (B) Cobalt chloride microinjected in the A7 area also blocked PH-mediated antinociception on the foot withdrawal test (○; p < 0.05). Normal saline microinjected near the A7 area (●) did not alter nociceptive responses.

Similar results were seen for the foot withdrawal response latencies. Microinjection of cobalt chloride into the A7 area significantly reduced PH-induced antinociception (Two way repeated measures ANOVA, F = 30.88 (1,171), p < 0.001; Fig. 5B), within 10 min after cobalt chloride injection. The mean withdrawal latencies of rats receiving cobalt chloride were significantly shorter than rats receiving normal saline in the A7 area (3.04 ± 0.13 vs. 4.08 ± 0.14 sec, resp.), and were not dependent on time (interaction effect, p > 0.05).

Microinjection of either cobalt chloride or normal saline into the A7 cell group in the absence of PH stimulation resulted in tail and foot withdrawal response latencies that did not differ significantly from control rats (not shown; p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

Recent studies implicate the PH in nociceptive modulation, but have not examined the mechanisms through which the PH produces this modulation. Our previous report demonstrated that PH-induced antinociception in a model of neuropathic pain is mediated in part by orexins receptors in the spinal cord dorsal horn (Jeong and Holden, 2009). The present study is the first to examine the PH and its recruitment of spinally-projecting A7 cells in a nociceptive model of pain. The actions of PH stimulation on spinally projecting noradrenergic A7 neurons were examined through the use of relatively selective α1- and α2-adrenoceptor antagonists in doses and injection volumes shown to block the effects of activating spinally projecting noradrenergic neurons (Holden et al., 1999; Nuseir and Proudfit, 2000; Wen et al., 2010). One of the major findings of the current experiments was that microinjection of 125 nmol carbachol, a dose shown to produce antinociception (Holden and Naleway, 2001; Holden et al., 2002; Holden et al., 2005; Holden et al., 2009; Jeong and Holden, 2009), produced antinociception partially blocked by IT administration of the α2-adrenoceptor antagonist yohimbine, but facilitated by the IT administration of the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist WB4101.

Several lines of evidence support the conclusion that carbachol stimulation of the PH produces α-adrenoceptor mediated modulation of nociception in the spinal cord dorsal horn via connections with the A7 area. First, in Sprague-Dawley rats derived from Sasco, as used in the present study, A7 noradrenergic neurons project to the spinal cord in a relatively dense innervation of the dorsal horn (Clark and Proudfit, 1991; West et al., 1993). Second, while the PH contains a direct projection to the spinal cord, it contains very few tyrosine-hydroxylase-immunoreactive neurons, and none of these have been shown to project to the spinal cord (Abrahamson and Moore, 2001). However, evidence exists that the PH does innervate the pontine parabrachial area, which contains the A7 cell group (Veazey et al., 1982; Vertes and Crane, 1996). Third, antinociception from stimulating the PH with carbachol was reduced or blocked by pretreatment of the PH with the cholinergic antagonist atropine sulfate, suggesting that carbachol-induced antinociception is mediated by cholinergic receptors in the PH. These results support and extend the findings of others that cholinergic receptors play a role in PH mechanisms. For example, injection of muscarinic and nicotinic antagonists into the PH affect hippocampal theta wave activity (Bocian and Konopacki, 2004), and choline-induced activation of the α7 nicotinic receptor in histaminergic tuberomammillary neurons of the PH affect cognition, alertness and sleep-wakefulness cycles (Uteshev and Knot, 2005; Gusev and Uteshev, 2010). Fourth, PH-induced antinociception was blocked by application of IT yohimbine, and facilitated by IT application of WB4101, suggesting that α2-adrenoceptors promote antinociception and α1-adrenoceptors promote nociceptive responses. This α-adrenergic opposing response has been observed following application of morphine (Holden, 1999) or bicuculline (Nuseir and Proudfit, 2000) directly to the A7 area, and from stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus, an area that recruits A7 cells as part of the descending nociceptive modulatory system (Holden and Naleway, 2001; Holden et al., 2002). Furthermore, in the present study, PH-induced antinociception was blocked following microinjection of cobalt chloride into the A7 cell group. Cobalt chloride reversibly blocks all synaptic activity within the area of microinjection (Kretz, 1984). These lines of evidence provide converging support for our hypothesis that PH-induced antinociception is mediated in part by innervation of the A7 catecholamine cell group.

Our finding that yohimbine blocks PH-induced antinociception supports and extends the work of others that shows that α2-adrenoceptor antagonists interfere with antinociception, as yohimbine blocks electrical (Takeda et al., 2006, Wen et al., 2010) or formalin-induced diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC) in rat (Wen et al., 2010), the effect of gabapentin-mediated antinociception in sciatic nerve ligation (Tanabe et al., 2005), and the antinociceptive effect of tramadol in rat (Li et al., 2012). Atipamazole blocks nerve-injury neuropathic pain in rat (Bee et al., 2011). In a model of post-operative pain, idazoxan blocks the effects of milnacipran, a 5-HT and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor effective for mechanical hyperalgesia (Obata et al., 2010), and completely reverses the antihyperalgesic and antiallodynic effects of clonidine, as well as its suppressive effect on ligated sciatic nerve NR1 phosphorylation in the spinal cord dorsal horn (Roh et al., 2008). It is well-documented that α2- adrenoceptors play an important role in the endogenous descending nociceptive modulatory system with most α2-adrenoceptors residing on the terminals of descending fibers, local spinal neurons, or central terminals of primary afferent fibers in the dorsal horn (Fairbanks et al., 2009). While we did not test for the specific α2 receptor subtype, evidence is supportive for a strong role for the α2a subtype (Wang et al., 2002; Fairbanks et al., 2009; Roh et al., 2010), and to a lesser extent, the α2c subtype (Chen et al., 2008; Roh et al., 2010) in providing antinociceptive effects.

Unlike α2- adrenoceptors, α1-adrenoceptor antagonists do not mediate antinociception in herpes zoster-like skin lesions (Sasaki et al., 2003; Mantovani et al., 2006) or in noxious heat stimuli in awake monkeys (Thomas et al., 1993), but do potentiate foot withdrawal responses from microinjection of morphine in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray (Fang and Proudfit, 1998). Recently, Zhang and Tan (2011) showed that pretreating cultured dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cells with either the α1-adrenocpetor antagonists phentolamine or prazosin inhibits enhanced firing of these cells induced by norepinephrine. Application of nerve growth factor to DRG cells induces a two-fold increase in α1b-adrenoceptor expression, but not α2 expression, augmenting neuronal responsiveness to norepinephrine acting at α1-adrenoceptors and contributing to the development of pain sensitization. Taken together, these findings lend support to the idea that α1-adrenoceptors facilitate nociception in the spinal cord.

A limitation of the present study is the difficulty in determining the precise microinjection size. The factors considered with size of microinjection are injection spread and amount of available solution relative to the injector location. Injection spread is affected by the molecular weight, concentration (Myers and Hoch, 1978; Nicholson, 1985) and water solubility of the solution, as well as injector tip size (Sakai et al., 1979) and neuroanatomical features of the injection site (Nicholson, 1985; Sakai et al., 1979; Lum et al., 1984). Microinjections of 0.5 μl or less limit the average spread of injection (Myers and Hoch, 1978). While recent findings indicate that a 0.5 μl injection of [3H]muscimol into subcortical structures produces a labeled area of over 5 mm2 15 minutes after injection (Edeline et al., 2002), others have reported smaller areas of spread. For example, labeled atropine injected in the hypothalamus (Grossman and Stumpf, 1969), [14C]dopamine injected into the brain stem (Myers and Hoch, 1978) and [14C]lidocaine and [3H]muscimol injected intracortically (1 μl over 4 min; Martin, 1991) produce average injection sites of about 1–1.5 mm within the first 20 min post injection. Our microinjections of 0.5 μl likely fall within these parameters.

The amount of available solution relative to the injection location also should be considered. For example, the amount of [14C]dopamine recovered 0.5 mm from the injection site is only 25% of the amount injected, increasing to 45% 15 min post injection (Myers and Hoch, 1978). Nor does diffusion of solution necessarily equate with neuronal activation. Grossman and Stumpf (1969) found that labeled atropine at sites away from the immediate microinjection location is 2,000–10,000 times lower than that needed to effectively block carbachol-induced behavior changes. Thus, it cannot be assumed that efficacy of the agonist is uniform across the injection site and is most likely optimally effective nearest the cannula. Findings from our previous work support this idea, as microinjection of carbachol into the ventral thalamus just dorsal to the PH (Jeong and Holden, 2009; Holden and Pizzi, 2009), the nigrostriatal bundle adjacent to the PH (Holden et al., 2002), and the internal capsule adjacent to the lateral hypothalamus (Holden, Farah, et al., 2005; Holden et al., 2002) produced withdrawal latencies similar to baseline measurements. Microinjector placements within the PH and lateral hypothalamus produced longer withdrawal latencies. Finally, we showed previously that 62 nmol of carbachol, half of the dose used in the present study, produced response latencies similar to control rats when microinjected into the PH (Jeong and Holden, 2009) or the lateral hypothalamus (Holden and Naleway, 2001). Given our use of a small microinjector tip, the evidence that neurons closer to the microinjector tip are more likely to be activated than neurons farther away, and the lack of response from a smaller dose of carbachol, the probability that our results came from stimulating neurons outside of the PH is small.

In the present study, unilateral microinjection of carbachol did not produce significant differences between left and right foot withdrawal latencies. The PH projection to the parabrachial area, including the A7 area, is predominantly unilateral, but there is a small contralateral projection (Vertes and Crane, 1996). Similarly, the A7 cell group sends axons to both the ipsilateral and contralateral dorsal horn (Clark and Proudfit, 1991). We found that unilateral microinjection of cobalt chloride in the A7 area completely blocked PH-induced antinociception for both feet. If the contralateral connection between the left PH and A7 area was significantly involved, such a blockade would not be expected for the right foot because the contralateral PH projection would activate descending input to the right dorsal horn. It seems likely that the lack of foot withdrawal differences is due to the bilateral projection of the A7 cell group to the dorsal horn because blockade of synaptic activity in the left A7 cell group prevented PH-induced antinociception in both feet. This idea is supported by the findings that unilateral stimulation of the A7 cell group either electrically (Yeomans et al., 1992) or chemically (Yeomans and Proudfit, 1992) produces bilateral effects.

In summary, the results of the present study demonstrated that microinjection of carbachol in the PH produces antinociception facilitated by α2-adrenoceptors and opposed by α1-adrenoceptors in the spinal cord dorsal horn. The converging evidence is suggestive that the PH makes connections in part with spinally descending noradrenergic neurons in the A7 catecholamine cell group that act at the dorsal horn to exert opposing effects on nociception.

Highlights.

Stimulating the posterior hypothalamus (PH) produces antinociception.

Dorsal horn α2-adrenoceptors mediate antinociception.

Dorsal horn α1-adrenoceptors mediate an opposing hyperalgesic effect.

Blockade of spinally descending noradrenergic A7 cells blocks PH antinociception.

PH-induced antinociception is mediated in part by connections with the A7 cell group.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by USPHS grant NR04778 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) at the National Institutes of Health. NINR had no involvement in the conduct of this study, or in publication decisions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Monica Wagner, Email: mawag@umich.edu.

Janean E. Holden, Email: holdenje@umich.edu.

References

- Abrahamson E, Moore R. The posterior hypothalamic area: Chemoarchitecture and afferent connections. Brain Res. 2001;889:1–22. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajic D, Commons K. Visualizing acute pain-morphine interaction in descending monoamine nuclei with Fos. Brain Res. 2010;1306:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch T, Falk D, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the posterior hypothalamic area in intractable short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT) Cephalgia. 2011;13:1405–1408. doi: 10.1177/0333102411409070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch T, Levy MJ, et al. Differential modulation of nociceptive dural input to [hypocretin] orexin A and B receptor activation in the posterior hypothalamic area. Pain. 2004;109:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch T, Pinsker MO, et al. Hypothalamic deep brain stimulation for cluster headache: Experience from a new multicase series. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:285–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bee L, Bannister K, et al. Mu-opioid and noracrenergic α(2)-adrenoceptor contributions to the effects of tapentadol on spinal electrophysiological measures of nociception in nerve-injured rats. Pain. 2011;152:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocian R, Konopacki J. The effect of posterior hypothalamic injection of cholinergic agents on hippocampal formation theta in freely moving cat. Brain Res Bull. 2004;63:283–294. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain JS, Green AL, et al. Local field potentials reveal a distinctive neural signature of cluster headache in the hypothalamus. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:1165–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruinstroop E, Cano G, et al. Spinal projections of the A5, A6 (locus coeruleus), and A7 noradrenergic cell groups in rats. J Comp Neurol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cne.23024. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavdar S, Onat F, et al. The afferent connections of the posterior hypothalamic nucleus in the rat using horseradish peroxidase. J Anat. 2001;198:463–472. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19840463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Song B, et al. Inhibition of opioid release in the rat spinal cord by alpha2C adrenergic receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:944–953. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark FM, Proudfit HK. The projection of noradrenergic neurons in the A7 catecholamine cell group to the spinal cord in the rat demonstrated by anterograde tracing combined with immunocytochemistry. Brain Res. 1991;547:279–288. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90972-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordella R, Franzini A, et al. Hypothalamic stimulation for trigeminal neuralgia in multiple sclerosis patients: Efficacy on the paroxysmal ophthalmic pain. Mult Scler. 2009;5:1322–1328. doi: 10.1177/1352458509107018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle C, Maxwell D. Catecholamine innervation of the spinal dorsal horn: A correlated light and electron microscopic analysis of tyrosine-hydroxylase-immunoreactive fibers in the cat. Neuroscience. 1991a;45:161–176. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle C, Maxwell D. Ultrastructureal analysis of noradrenergic nerve terminals in the cat lumbosacral spinal dorsal horn: A dopamine-B-hydroxylase immunocytochemical study. Brain Res. 1991b;563:329–333. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91557-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edeline J, et al. Muscimol diffusion after intracerebral microinjections: A re-evaluation based on electrophysiological and autoradiographic quantifications. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;78:100–124. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2001.4035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks C, Stone L, et al. Pharmacological profiles of alpha 2 adrenergic receptor agonists identified using genetically altered mice and isobolographic analysis. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;123:224–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang F, Proudfit HK. Antinociception produced by microinjection of morphine in the periaqueductal gray is enhanced in the rat foot, but not the tail, by intrathecal injection of alpha 1-adrenoceptor antagonists. Brain Res. 1998;790:14–24. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01441-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilov Y, Perekrest S, et al. Intracellular expression of c-Fos protein in various structures of the hypothalamus in electrical pain stimulation and administration of antigens. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2008;38:87–92. doi: 10.1007/s11055-008-0012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goadsby P. Neuromodulatory approaches to the treatment of trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97:99–110. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-33081-4_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman S, Stumpf W. Intracranial drug implants: An autoradiographic analysis of diffusion. Science. 1969;166:1410–1412. doi: 10.1126/science.166.3911.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusev A, Uteshev V. Physiological concentrations of choline activate native alpha7-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the presence of PNU-120596 [1-(5-chloro-2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-(5-methylisoxazol-3-yl)-urea] J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332:588–598. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.162099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagihira S, Senba E, et al. Fine structure of noradrenergic terminals and their synapses in the rat spinal dorsal horn: An immunohistochemical study. Brain Res. 1990;526:73–80. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess A, Sergejeva M, et al. Imaging of hyperalgesia in rats by functional MRI. Eur J Pain. 2007;11:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden J, Naleway E, et al. Stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus produces antinociception mediated by 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B and 5-HT3 receptors in the rat spinal cord dorsal horn. Neuroscience. 2005;135:1255–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden J, Pizzi J, et al. An NK1 receptor antagonist microinjected into the periaqueductal gray blocks lateral hypothalamic-induced antinociception in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2009;453:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.01.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden JE, Naleway E. Microinjection of carbachol in the lateral hypothalamus produces opposing actions on nociception mediated by α1- and α2-adrenoceptors. Brain Res. 2001;991:27–36. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02567-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden JE, Schwartz E, Proudfit H. Microinjection of morphine in the A7 catecholamine cell group produces opposing effects on nociception that are mediated by α1- and α2-adrenoceptors. Neuroscience. 1999;91:979–990. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00673-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden JE, Van Poppel A, et al. Antinociception from lateral hypothalamic stimulation may be mediated by NK1 receptors in the A7 catecholamine cell group in rat. Brain Res. 2002;953:195–204. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong Y, Holden J. The posterior hypothalamus modulates nociception via alpha adrenoceptors in the spinal cord dorsal horn. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 2005;31 [Google Scholar]

- Jeong Y, Holden J. The role of spinal orexin-1 receptors in posterior hypothalamic modulation of neuropathic pain. Neuroscience. 2009;159:1414–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurgens T, Leone M, et al. Hypothalamic deep-brain stimulation modulates thermal sensitivity and pain thresholds in cluster headache. Pain. 2009;146:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretz R. Local cobalt injection: A method to discriminate presynaptic axonal from postsynaptic neuronal activity. J Neurosci Meth. 1984;11:129–135. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone M, Bussone G. Pathophysiology of trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:755–764. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone M, Franzini A, et al. Hypothalamic deep brain stimulation in the treatment of chronic cluster headache. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2010;3:187–195. doi: 10.1177/1756285610370722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone M, Franzini A, D’Andrea G, Broggi G, Casucci G, Bussone G. Deep brain stimulation to relieve drug resistant SUNCT. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:924–927. doi: 10.1002/ana.20507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Chen S, et al. The antinociceptive effect of intrathecal tramadol in rats: The role of alpha2-adrenoceptors in the spinal cord. J Anesth. 2012;26:230–235. doi: 10.1007/s00540-011-1267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light AR. The initial processing of pain and its descending control: Spinal and trigeminal systems. Basel: Karger; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lum J, Nguyen T, Felpel L. Drug distribution in solid tissue of the brain following chronic, local perfusion utilizing implanted osmotic minipumps. J Pharm Methods. 1984;12:141–147. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(84)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning BH, Franklin KBJ. Morphine analgesia in the formalin test: Reversal by microinjection of quaternary naloxone into the posterior hypothalamic area or periaqueductal gray. Behav Brain Res. 1998;92:97–102. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani M, Kaster M, et al. Mechanisms involved in the antinociception caused by melatonin in mice. J Pineal Res. 2006;41:382–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. Autoradiographic estimation of the extent of reversible inactivation produced by microinjection of lidocaine and muscimol in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1991;127:160–164. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90784-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May A. Hypothalamic deep-brain stimulation: Target and potential mechanism for the treatment of cluster headache. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:799–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Przewlocki, et al. Evidence for a role of the ventro-medial posterior hypothalamus in nociceptive processes in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982;18:901–907. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(83)80013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min M, Wu Y, et al. Physiological and morphological properties of, and effect of substance P on, neurons in the A7 catecholamine cell group in rats. Neuroscience. 2008;153:1020–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min M, Wu Y, et al. Roles of A-type potassium currents in tuning spike frequency and integrating synaptic transmission in noradrenergic neurons of the A7 catecholamine cell group in rats. Neuroscience. 2010;168:633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers R, Hoch D. 14C-dopamine microinjected into the brain-stem of the rat: Dispersion kinetics, site content, and functional dose. Brain Res Bull. 1978;3:601–609. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(78)90006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson C. Diffusion from an injected volume of a substance in brain tissue with arbitrary volume fraction and tortuosity. Brain Res. 1985;333:325–329. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91586-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuseir K, Heidenreich BA, et al. The antinociception produced by microinjection of a cholinergic agonist in the ventromedial medulla is mediated by noradrenergic neurons in the A7 catecholamine cell group. Brain Res. 1999;822:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuseir K, Proudfit HK. Bidirectional modulation of nociception by GABA neurons in the dorsolateral pontine tegmentum that tonically inhibit spinally projecting noradrenergic neurons. Neuroscience. 2000;96:773–783. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00603-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obata H, Kimura M, et al. Monoamine-dependent, opioid-independent antihypersensitivity effects of intrathecally administered milnacipran, a serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor, in a postoperative pain model in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;344:1059–1065. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.168336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Sterotaxic Coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Proudfit HK. The behavioural pharmacology of the noradrenergic descending system. In: Besson J-M, editor. Toward the Use of Noradrenergic Agonists for the Treatment of Pain. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1992. pp. 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes DL, Liebeskind JC. Analgesia from rostral brain stem stimulation in the rat. Brain Res. 1978;143:521–532. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90362-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh D, Kim H, et al. Intrathecal clonidine suppresses phosphorylation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor NR1 subunit in spinal dorsal horn neurons of rats with neuropathic pain. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:693–700. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817e7319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh D, Seo H, et al. Activation of spinal alpha-2 adrenoceptors, but not nu-opioid receptors, reduces the intrathecal N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced increase in spinal NR1 subunit phosphorylation and nociceptive behaviors in the rat. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:622–629. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c8afc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero A, Rojas S, et al. A 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose microPET imaging study to assess changes in brain glucose metabolism in a rat model of surgery-induced latent pain sensitization. Anesthesiology. 2011 Sep 29; doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823425f2. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai M, Swartz B, Woody C. Controlled micro release of pharmacological agents: Measurements of volume ejected in vitro through fine tipped glass microelectrodes by pressure. Neuropharmacology. 1979;18:209–213. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(79)90063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A, Takasaki I, et al. Roles of alpha-adrenoceptors and sympathetic nerve in acute herpetic pain induced by herpes simplex virus inoculation in mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 2003;92:329–336. doi: 10.1254/jphs.92.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda M, Tanimoto T, et al. Activation of alpha2-adrenoreceptors suppresses the excitability of C1 spinal neurons having convergent inputs from tooth pulp and superior sagittal sinus in rats. Exp Brain Res. 2006;174:210–220. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0442-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe M, Takasu K, et al. Role of descending noradrenergic system and spinal alpha2-adrenergic receptors in the effects of gabapentin on thermal and mechanical nociception after partial nerve injury in the mouse. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:703–714. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706109. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15678083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D, Anton F, et al. Noradrenergic and opioid systems interact to alter the detection of noxious thermal stimuli and facial scratching in monkeys. Pain. 1993;55:63–70. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90185-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uteshev V, Knot H. Somatic Ca(2+) dynamics in response to choline-mediated excitation in histaminergic tuberomammillary neurons. Neuroscience. 2005;134:133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veazey R, Amaral D, et al. The morphology and connections of the posterior hypothalamus in the cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis). II. Efferent connections. J Comp Neurol. 1982;207:135–156. doi: 10.1002/cne.902070204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertes RP, Crane AM. Descending projections of the posterior nucleus of the hypothalamus: Phaseolus vulgaris Leucoagglutinin analysis in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1996;374:607–631. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19961028)374:4<607::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walcott B, Bamber N, et al. Successful treatment of chronic paroxysmal hemicrania with posterior hypothalamic stimulation: Technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:E997. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000345937.05186.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhang Z, et al. Effect of antisense knock-down of alpha(2a)- and alpha(2c)-adrenoceptors on the antinociceptive action of clonidine on trigeminal nociception in the rat. Pain. 2002;98:27–35. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00464-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Wang C, et al. DNIC-mediated analgesia produced by a supramaximal electrical or high-dose formalin conditioning stimulus: Roles of opioid and alpha2-adrenergic receptors. J Biomed Sci. 2010;17:19–31. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-17-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West WL, Yeomans DC, et al. The function of noradrenergic neurons in mediating antinociception induced by electrical stimulation of the locus coeruleus in two different sources of Sprague-Dawley rats. Brain Res. 1992;626:127–135. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90571-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westlund K, Bowker R, et al. Origins of spinal noradrenergic pathways demonstrated by retrograde transport of antibody to dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. Neurosci Lett. 1981;25:243–249. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90399-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westlund K, Bowker R, et al. Noradrenergic projections to the spinal cord of the rat. Brain Res. 1983;263:15–31. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91196-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westlund K, Carlton S, et al. Direct catecholamine innervation of primate spinothalamic tract neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1990;299:178–186. doi: 10.1002/cne.902990205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans DC, Clark FM, et al. Antinociception induced by electrical stimulation of spinally-projecting noradrenergic neurons in the A7 catecholamine cell group of the rat. Pain. 1992;48:449–461. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90098-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans DC, proudfit HK. Antinociception induced by microinjection of substance P into the A7 catecholamine cell group in the rat. Neuroscience. 1992;49:681–691. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90236-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Tan Y. Nerve growth factor augments neuronal responsiveness to noradrenaline in cultured dorsal root ganglion neurons of rats. Neuroscience. 2011;193:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]