Abstract

AKT1 (also known as protein kinase B, α), a serine/threonine kinase of AKT family, has been implicated in both schizophrenia and methamphetamine (Meth) use disorders. AKT1 or its protein also has epistatic effects on the regulation of dopamine-dependent behaviors or drug effects, especially in the striatum. The aim of this study is to investigate the sex-specific role of Akt1 in the regulation of Meth-induced behavioral sensitization and the alterations of striatal neurons using Akt1 −/− mice and wild-type littermates as a model. A series of 4 Experiments were conducted. Meth-induced hyperlocomotion and Meth-related alterations of brain activity were measured. The neural properties of striatal medium spiny neurons (MSNs) were also characterized. Further, 17β-estradiol was applied to examine its protective effect in Meth-sensitized male mice. Our findings indicate that (1) Akt1 −/− males were less sensitive to Meth-induced hyperlocomotion during Meth challenge compared with wild-type controls and Akt1 −/− females, (2) further sex differences were revealed by coinjection of Meth with raclopride but not SCH23390 in Meth-sensitized Akt1 −/− males, (3) Meth-induced alterations of striatal activity were confirmed in Akt1 −/− males using microPET scan with 18F-flurodeoxyglucose, (4) Akt1 deficiency had a significant impact on the electrophysiological and neuromorphological properties of striatal MSNs in male mice, and (5) subchronic injections of 17β-estradiol prevented the reduction of Meth-induced hyperactivity in Meth-sensitized Akt1 −/− male mice. This study highlights a sex- and region-specific effect of Akt1 in the regulation of dopamine-dependent behaviors and implies the importance of AKT1 in the modulation of sex differences in Meth sensitivity and schizophrenia.

Key words: Akt1 mice, methamphetamine, behavioral sensitization, sex differences, striatum, medium spiny neuron, microPET scan, 17β-estradiol, schizophrenia, meth-amphetamine use disorders

Introduction

AKT1 (protein kinase B, α), a serine/threonine kinase of the AKT family, is involved in multiple biological processes and several severe psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia and methamphetamine (Meth) use disorders. Accumulating evidence from human genetic studies suggests that the AKT1 gene is associated with the genetic etiology of schizophrenia in Caucasian families of European descent1 and several other ethnic groups.2 Positive associations between several haplotypes of AKT1 and Meth abuse/dependence have also been reported in the Japanese population3 and in a systematic review study.4 It is known that Meth, a dopamine enhancer and a potent illicit psychostimulant, can cause psychotic symptoms indistinguishable from schizophrenia in abusers and aggravate psychosis in patients with schizophrenia.4,5 Meth users and schizophrenic patients also share some similarities in their numerous sex-based differences,6–9 and some sex-specific behavioral deficits have been recapitulated in Akt1-deficient mice.10 Interestingly, estrogen signaling, an important cause of sex differences, may be disturbed in schizophrenic patients,11,12 and estrogen treatment can also ameliorate schizophrenia symptoms.13,14 Accordingly, the “estrogen protection hypothesis” has been proposed to account for these gender differences and suggests that estrogen provides protection from the development of schizophrenia and mitigates schizophrenic symptoms.11 However, the potential involvement of AKT1 in the pathogenesis of these 2 disorders and their sex-specific deficits remains much unclear.

Abnormalities in the dopamine system (or the dopamine hypothesis) have long been implicated in explanations of schizophrenia and Meth-associated psychosis.15 Studies of the postmortem brains of schizophrenic patients,1,16 Akt1-deficient mice,10,17 and functional neuroimaging in humans18 support the idea that genetic variations in AKT1 or its protein have epistatic effects on the regulation of dopamine-dependent functions or drug effects. Emerging evidence also indicates that AKT is directly downstream of dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) activation and DRD2-mediated AKT interacts with the β-arrestin2/PP2A signaling complex in the regulation of dopamine signaling cascades and the expression of dopamine-dependent behaviors, especially in the striatum.19–21 Anatomically, the striatum, the principal input structure of the basal ganglia that influences motor control and reward-based learning, receives prominent dopaminergic inputs from the midbrain through the mesocorticolimbic and nigrostriatal dopamine systems.22,23 The striatal medium spiny neurons (MSNs) are the principal (over 95%) neurons in the striatum and act as the main output neurons to form the predominantly gamma-aminobutyric acidergic (GABAergic) microcircuit.24 The impact of AKT1 on MSNs remains unclear, but AKT-mediated phosphorylation has been reported to regulate synaptic strength and synaptic plasticity through an increase of the number of GABAA receptors.25 Thus, activation of AKT1 might interact with the dopaminergic system to regulate striatal MSNs, and this could eventually lead to abnormalities in striatum-dependent behaviors or the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and Meth use disorders.

Meth-associated psychosis has been considered to be a pharmacological or environmental disease that produces an agent model of schizophrenia due in part to similarities in clinical presentation and response to treatment. In the context of drug addiction and schizophrenia, the behavioral sensitization model is well established and widely used in laboratory animals.26,27 In rodents, repeated systemic Meth/amphetamine administrations not only result in enduring sensitized behaviors (such as enhanced locomotor activity, more rapid onset, and greater intensity of stereotypy) in response to subsequent Meth/amphetamine challenges but also result in elevated striatal dopamine release.28–31 This experimental procedure provides a potential animal model to test the impact of AKT1 deficiency in the regulation of dopamine-related sensitization and its susceptibility to schizophrenia-related symptoms and Meth-associated psychosis, especially in mutant mouse models.

Given the involvement of AKT1 in the dopamine signaling cascade and in the pathogenesis of Meth abuse disorder and schizophrenia, we conducted a series of 4 experiments to investigate the sex-specific role of Akt1 in the regulation of dopamine-dependent behavior and striatal activity by measuring Meth-induced alterations in behavioral sensitization (experiment 1) and brain activity using small animal positron emission tomography (microPET) scan (experiment 2). Basal levels of neurotransmitters and basal electrophysiological/neuromorphological properties of striatal MSNs were further examined to characterize basal differences between male Akt1 −/− mice and their wild-type (WT) controls (experiment 3). A series of daily injections of 17β-estradiol was applied to further examine the “estrogen protection hypothesis” in Meth-treated male mice (experiment 4).

Materials and Methods

Animals

All Akt1 homozygous knockout (Akt1 −/−) and WT mice used in this study were generated from Akt1 heterozygous breeding pairs with a C57BL/6J genetic background (n > 10). The details have been described elsewhere10,17,32 and in the online supplementary Methods.

Experiment 1A: Evaluation of Meth-Induced Behavioral Sensitization

Meth-induced behavioral sensitization was used to evaluate dopamine-related behavioral alterations in male and female Akt1 −/− mice and their WT littermates (n = 8–10 each, 4 months old). The behavioral sensitization procedure (modified from)33 consisted of 6 daily injections of Meth (from Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health, Taipei, Taiwan; 2.0mg/kg, ip, dissolved in saline), followed by 1 day of withdrawal and a 1.0mg/kg Meth challenge on day 8. The locomotor activity of each mouse was recorded and analyzed using Ethovision video tracking system (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, Netherlands) on days 1, 3, 6, and 8. On the days of measurement of locomotor activity, the total distance traveled (cm) by each mouse was recorded in a polyvinylchloride chamber (48×24×25cm) for a 60-min baseline period, followed by a 15-min saline baseline after a saline injection, and then 60min of locomotion was recorded after the injection of Meth.

Experiment 1B: Coinjections of Meth With Dopaminergic Antagonists in Meth-Sensitized Mice

To further examine the sex-specific effect of Akt1 on the regulation of dopamine D1-/D2-like receptor-dependent suppression of Meth-induced hyperlocomotion, Meth-sensitized mice from the previous experiment were further challenged by the coinjection of Meth (1.0mg/kg), with an optimal effective dose of raclopride (from Sigma-Aldrich, a dopamine D2-like receptor antagonist, 1.0mg/kg, ip) on day 10 and SCH23390 (from Sigma-Aldrich, a dopamine D1-like receptor antagonist, 0.01mg/kg, ip) on day 12. A 1-day washout interval between treatments was applied to avoid any carryover effect. On each testing day, locomotor activity was measured as described above. The net value of suppressed locomotion is equal to the difference between locomotion induced by coinjections on the testing day and Meth-induced locomotion on day 8.

Experiment 2: Evaluation of Brain Activity Using MicroPET Scanning

Male and female Akt1 –/– mice and their WT littermates (n = 5 each) were used to evaluate brain activity using microPET scans (eXplore Vista DR, GE Healthcare) with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG). Each mouse received a baseline PET-CT (FDG) scan and another PET-CT scan after Meth administration (4mg/kg, ip, FDG + Meth) 7–10 days later. A slightly higher dose of Meth was used here to ensure that acute Meth-induced brain activities can be successfully detected using animal PET scan. Five regions of interest (ROI, including the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), caudate putamen (CPu), nucleus accumbens (NAc), total striatum (CPu + NAc), and cerebellum) were selected. The average standardized uptake values (SUV) of each ROI were obtained, and the normalized SUV was calculated as SUVtarget ROI/SUVcerebellum. The ratio of Meth-induced brain metabolic change in each dopamine-related ROI was further calculated as normalized SUV FDG + Meth/normalized SUV FDG. The basic method has been described previously,34 and details are presented in the online supplementary Methods.

Experiment 3A: Examination of Basal Levels of Neurotransmitters and Their Metabolites in the Brain of Male Mice

The basal levels of L-dopa, dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, and their metabolites were measured using high-performance liquid chromatography in the frontal cortex, striatum, somatosensory cortex, hippocampus, and midbrain of male Akt1 –/– and WT littermate mice (n = 8 each). The method has been described previously,35 and details are presented in the online supplementary Methods.

Experiment 3B: Examination of Basal Electrophysiological and Neuromorphological Properties of Striatal MSNs in Male Mice

Male Akt1 –/– and WT mice (approximately 8 weeks old) were used in this experiment. Striatal MSNs were identified in coronal forebrain slices,36,37 and their electrophysiological and morphological properties were recorded with patch pipettes. Miniature excitatory/inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs/mIPSCs) activity, which is caused by spontaneous and random release of glutamate/GABA from presynaptic vesicles in the absence of an action potential, was recorded to examine the excitatory/inhibitory synaptic inputs to the MSNs. The recorded neurons were labeled with biocytin during recording and visualized with biocytin labeling. The neurons were reconstructed using the Neurolucida system (MBF Bioscience). For each available neuron (n = 10), we measured the morphological variables and performed a Sholl analysis to evaluate the dendritic complexity.10,17 All details are described in the online supplementary Methods.

Experiment 4: Evaluation of the Effect of 17β-Estradiol on the Rescue of Meth-Induced Hyperlocomotion in Male Akt1–/– Mice

In this experiment, the protective effect of 17β-estradiol was evaluated in Meth-treated male mice. Another batch of 4 month-old male Akt1 –/– mice and their WT littermates was used in this experiment, and they were randomly assigned to one of the following 6 treatment groups (n = 11–13 each): (1) WT mice with vehicle (VEH) and saline (SAL) injections (WT-VEH-SAL group), (2) WT mice with 17β-estradiol (Estradiol) and SAL injections (WT-Estradiol-SAL group), (3) WT mice with VEH and Meth injections (WT-VEH-Meth group), (4) Akt1 –/– mice with VEH and Meth injections (the Akt1-VEH-Meth group), (5) WT mice with Estradiol and Meth injections (WT-Estradiol-Meth group), and (6) Akt1 –/– mice with Estradiol and Meth injections (Akt1-Estradiol-Meth group). The same behavioral sensitization procedure was applied as described above, and the males in each group received different treatments accordingly. From 4 days before to the first day of behavioral sensitization (total 12 days), each subject in the 3 VEH groups received a subcutaneous injection of 0.1ml of vehicle (0.9% saline with 0.3% gelatin) twice per day (12h apart), and each male in the 3 Estradiol groups received 2 daily (12h apart) injections of 1 μg (in 0.1ml of vehicle) of 17β-estradiol (Sigma-Aldrich) as described previously.38 As described before, Meth was dissolved in saline and administered intraperitoneally. The same recording method described above was used, and locomotor activity was recorded on days 1, 3, 6, and 8 of behavioral sensitization.

Statistics and Data Analyses

All of the data are presented as the mean + SE of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0 (SPSS Inc.), and the data were analyzed by 1-way or 2-way ANOVAs or 2-sample Student’s t test, where appropriate. A post hoc analysis was performed using Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test when the F values revealed a significant difference. A priori t tests (with Bonferroni adjustments when needed) were conducted to compare genotypic differences or to answer specific hypotheses. The comparisons of mEPSCs/mIPSCs were made using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to test whether any 2 of the distributions were identical. The details of statistical analysis for in vitro data were described in the online supplementary Methods. P values of < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Experiment 1A: Sex-Specific Effect of Akt1 on Meth-Induced Behavioral Sensitization

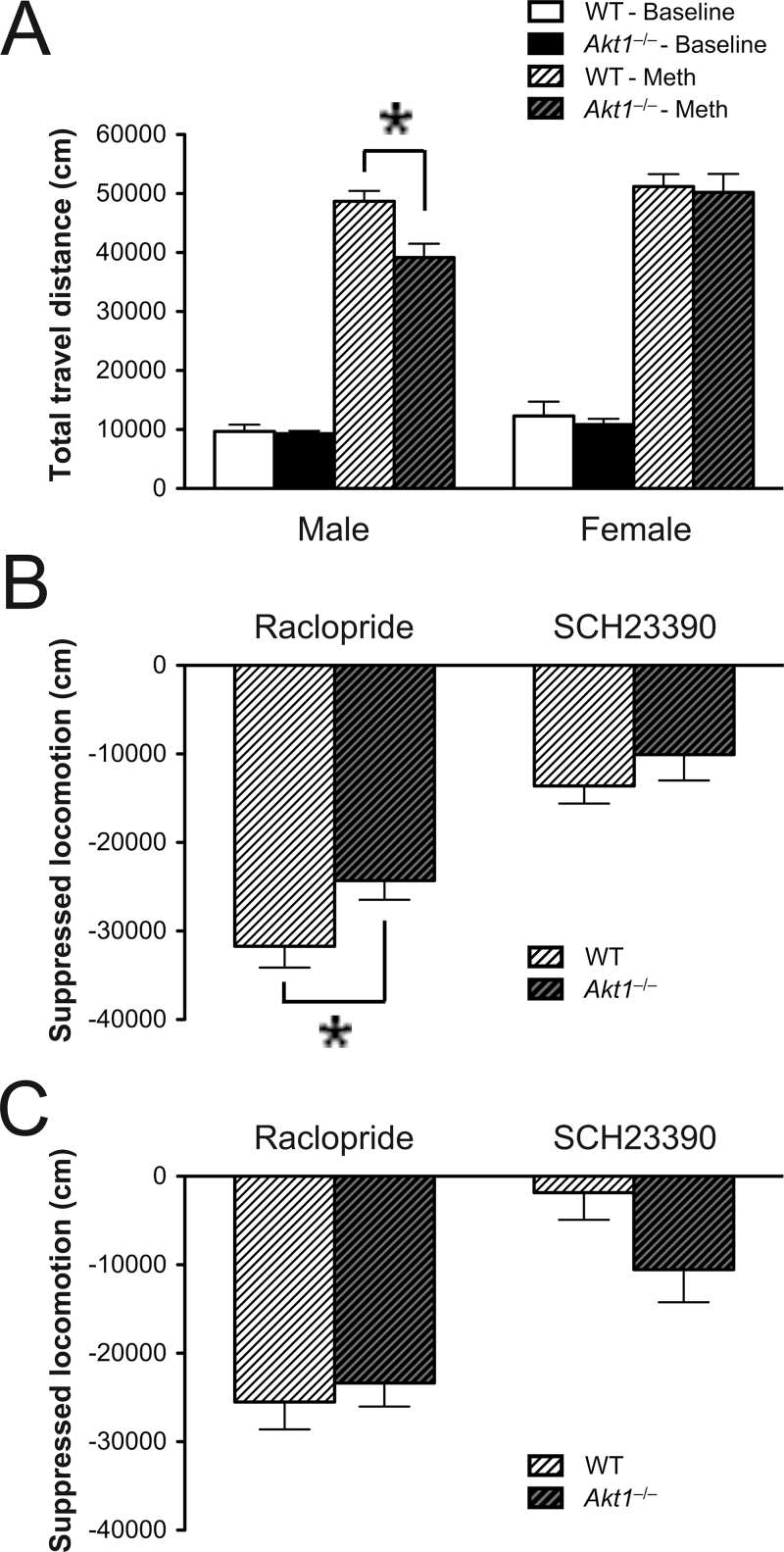

During the 6-day acquisition of Meth-induced behavioral sensitization, no significant genotypic differences were found among males or females. Over days, both WT and Akt1 −/− mice exhibited progressively more rapid onset to the peak of Meth-induced hyperlocomotion across days 1, 3, and 6 in males (F (2,26) = 111.355, P = .0001 < .05) and females (F (2,32) = 104.442, P = .0001 < .05), as depicted in online supplementary figures 1A and 1B. Compared with the 15-min saline baseline, the treatment of Meth induced significantly greater locomotor activity 15min after injection in all groups on each testing days (see online supplementary figures 1C and 1D). Priori t tests further revealed that Meth-induced hyperlocomotion on day 3 or day 6 was significantly greater than the one on day 1 for both WT and Akt1 −/− male and female mice (all P < .05). The results indicated that these mice demonstrated behavioral sensitization to Meth over days. On day 8 (the challenge day), no significant genotypic differences were found during the 60-min baseline (figure 1A) or during the 15-min saline baseline. However, priori t tests revealed that half dose of Meth challenge (ie, 1mg/kg) induced significantly or marginally higher hyperlocomotion on day 8 compared with Meth-induced hyperlocomotion on day 6 in WT females (51202.01±2096.508 vs 47069.46±2368.167cm, t(9) = 3.373, P = .008), Akt1 −/− females (50 204.251±3113.698 vs 43 961.926±3887.944cm, t(7) = 5.683, P = .0007), and WT males (48704.637±1740.095 vs 42465.181±4080.21cm, t(7) = 2.038, P = .08). In contrast, Akt1 −/− males did not displayed significantly enhanced Meth-induced hyperlocomotion on day 8 compared with the one on day 6 (40083.946 ± 1856.684 vs 39178.361±2333.7cm; t(7) = 0.31, P = .77). These findings indicated that all but male Akt1 −/− mice fully developed Meth-induced behavioral sensitization on day 8. Furthermore, as depicted in figure 1A, there were also significant main effects of genotype (F (1,29) = 4.875, P = .0353) and sex (F (1,29) = 8.05, P = .0082) for Meth-induced hyperactivity on day 8. The genotype × sex interaction was not statistically significant, but there was a trend toward statistical significance (F (1,29) = 3.202, P = 0.084). Fisher’s LSD post hoc analysis further indicated that male Akt1 −/− mice displayed significantly decreased Meth-induced hyperactivity compared with male WT controls (P < .05), whereas female mice did not show this genotypic difference. Accordingly, the following data were analyzed separately by sex.

Fig. 1.

Sex-specific effect of Akt1 on the regulation of methamphetamine (Meth)-induced behavioral sensitization (mean + SEM cm) in both male and female wild-type (WT) and Akt1 −/− mice (n = 8–10 each). (A) Total travel distance of both male and female WT and Akt1 −/− mice during the 1-h baseline and the 1-h Meth-induced hyperlocomotion on day 8 (the challenge day). (B, C) The net effects of raclopride (1.0mg/kg, ip) and SCH23390 (0.01mg/kg, ip) on the suppression of Meth-induced hyperlocomotion on days 10 and 12 in male and female mice, respectively. *P < .05.

Experiment 1B: The Sex-Specific Effect of Akt1 Was Further Revealed by Coinjections of Meth With Raclopride in Meth-Sensitized Mice

The net effects of raclopride and SCH23390 on the suppression of Meth-induced hyperlocomotion in males and females are shown in figures 1B and 1C, respectively. In the males, the coinjection of raclopride resulted in a significant suppression of Meth-induced hyperlocomotion in WT mice compared with Akt1 −/− mice (t(13) = −2.25, P = .042), whereas the coinjection of SCH23390 had no effect. In contrast to males, no significant genotypic difference was found in the females. These results indicate that raclopride (but not SCH23390) can exert its suppression effect on Meth-induced hyperlocomotion by acting on Akt1 and its downstream signaling, especially in the males. They also underline the importance of Akt1 in the modulation of DRD2-dependent signaling and dopamine-dependent behavior.

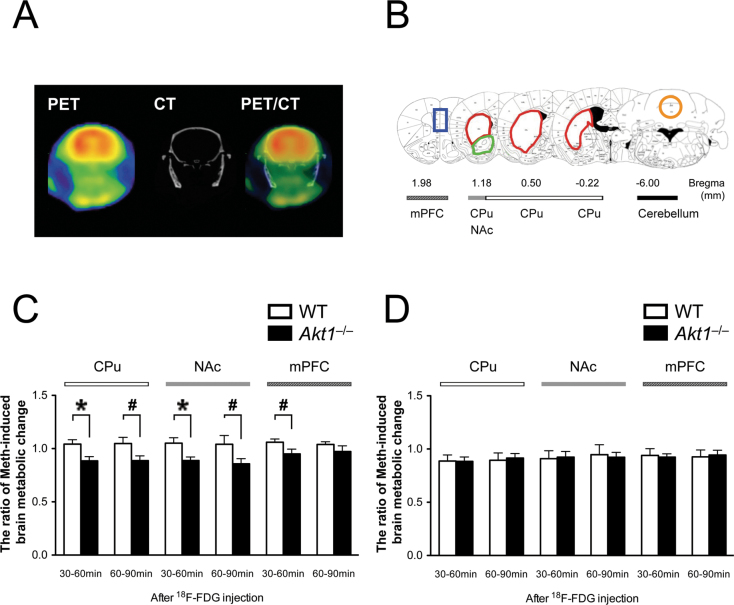

Experiment 2: Sex-Specific Effect of Akt1 in the Regulation of Meth-Induced Brain Activity Was Confirmed in the Striatum Using MicroPET With 18F-FDG

Representative microPET images of a mouse brain are shown in figure 2A, and regions of interest are illustrated in figure 2B. At the basal level, neither the male nor female mice displayed significant genotypic differences in their normalized SUV in any ROI (all P > .05, data not shown). In contrast, the ratio of Meth-induced brain metabolic change exhibited some significant genotypic differences in the CPu, NAc, and mPFC of the male mice (figure 2C), whereas no differences were found in the female mice (figure 2D). These microPET results indicated a region- and sex-specific reduction of Meth-induced activity in the brain of Akt1 −/− males, especially in the striatum at 30–60min after injection of FDG.

Fig. 2.

Examination of brain activity during baseline and after Meth injection using microPET with 18F-FDG. (A) Representative PET, CT, and PET-CT fusion images of a mouse coronal slice (on Bregma −0.22mm). (B) Mouse brain atlases highlighting the regions of interest, including the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC, in blue), caudate putamen (CPu, in red), nucleus accumbens (NAc, in green), and cerebellum (in orange, the reference point). (C, D) The ratio of Meth-induced brain metabolic change in the CPu, NAc, and mPFC of both male and female WT and Akt1 −/− mice, respectively. The ratio was calculated as the normalized SUV FDG + Meth/normalized SUV FDG. *P < .05; #P < .10.

Experiment 3A: Quantification of Basal Levels of Neurotransmitters and Their Metabolites in the Brains of Male Mice

As indicated in online supplementary table 1, among the 5 brain areas we examined, no significant genotypic differences in basal levels of neurotransmitters or their metabolites were found with the exception of norepinephrine. In comparison with WT controls, Akt1 −/− mice had significantly higher levels of norepinephrine in the frontal cortex and midbrain (both P < .05).

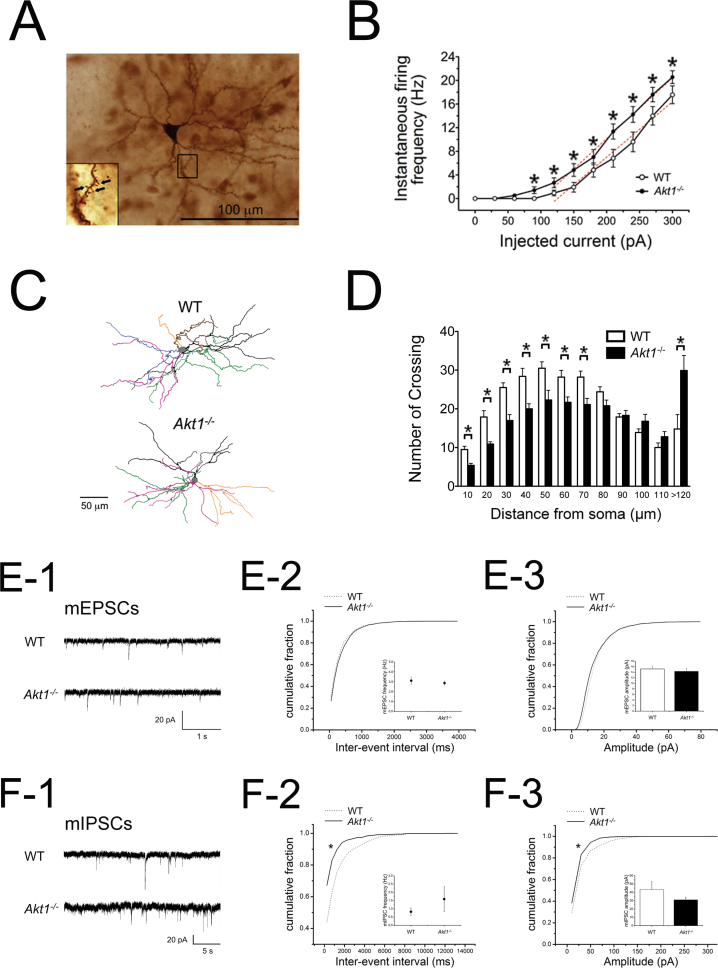

Experiment 3B: Altered Intrinsic Electrophysiological and Neuromorphological Properties of Striatal MSNs in Male Akt1−/− Mice

A representative image of a biocytin-labeled striatal MSN is shown in figure 3A. As indicated in table 1, concerning the intrinsic membrane properties, the Akt1 −/− group had slightly higher resting membrane potentials (t(35) = 2.776, P = .009) and significantly higher input resistances (t(78) = −3.426, P = .001) than those of the WT group. Regarding the firing patterns, the rheobase was significantly lower in the Akt1 −/− group compared with the WT group (t(80) = 2.133, P = .036). The current-firing frequency (I-ΔV) plot for the Akt1 −/− group displayed a significant shift to the left (F (1,90) = 4.783, P < .05), and its firing frequency increased significantly in response to multiple injected currents compared with the results obtained for the WT controls (P < .05, figure 3B). No genotypic differences were found in the input-output relationship or the input/output gain.

Fig. 3.

Examination of basal electrophysiological and neuromorphological properties (mean ± SEM) of striatal medium spiny neurons (MSNs) in male WT and Akt1 −/− mice. (A) A representative image of a biocytin-labeled striatal MSN. The insert shows 1 enlarged dendrite, and dendritic spines are indicated by black arrows. (B) The I-ΔV plot showing the instantaneous current-firing frequency (Hz). (C) Representative traces of striatal MSNs for WT and Akt1 −/− mice. The soma is labeled in gray; different colored lines represent different dendrites extending from the soma. (D) Sholl analysis of striatal MSNs. (E-1, F-1) Representative current traces of miniature excitatory/inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs/mIPSCs) recorded in voltage-clamp mode on striatal MSNs in male WT and Akt1 −/− mice, respectively. (E-2, F-2) Cumulative distribution analysis of mEPSC and mIPSC frequencies (inserts: mean frequency), respectively. (E-3, F-3) Cumulative distribution analysis of mEPSC and mIPSC amplitudes (inserts: mean amplitude), respectively. *P < .05 between 2 genotypes.

Table 1.

Summary Table of Intrinsic Electrophysiological and Neuromorphological Properties of Striatal MSNs in Male WT (Wild-Type) and Akt1 −/− Mice

| WT | Akt1 −/− | Statistical Result, P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic electrophysiological properties | |||

| Resting membrane potential (mV) | −82.049±0.601 (35) | −80.332±0.454 (38) | < .05 |

| Input resistance (MΩ) | 86.917±5.754 (41) | 114.754±5.728 (39) | < .05 |

| Average rheobase (pA) | 221.471±9.647 (34) | 191.25±9.77 (48) | < .05 |

| Gain (Hz/pA) | 0.094±0.009 (39) | 0.103±0.007 (53) | NS |

| Morphometric analysis | |||

| Soma size (μm2) | 131.648±15.629 (10) | 124.43±11.283 (10) | NS |

| Number of primary basal dendrites | 5.8±0.389 (10) | 4.1±0.277 (10) | < .05 |

| Average length of primary basal dendrites (μm) | 25.605±5.135 (10) | 12.165±3.112 (10) | < .05 |

| Number of branches | 27.3±1.383 (10) | 25±1.745 (10) | NS |

| Number of tips | 33.9±1.494 (10) | 29.5±1.939 (10) | NS |

| Total length of basal dendrites (μm) | 3527.01±138.898 (10) | 3063.19±194.378 (10) | .068 |

Note: NS, not significant.

The values are expressed as means ± SEM for each of the 2 groups and their sample sizes are indicated right after each value. Statistical analyses between 2 genotypes are shown in the right column. P values of < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Besides, representative traces of striatal MSNs from WT and Akt1 −/− mice are shown in figure 3C. As indicated in table 1, there were significant decreases in the number and average length of primary dendrites in Akt1 −/− mice compared with WT controls (t(18) = 3.562, P = .002 and t(18) = 2.238, P = .038, respectively). The Sholl analysis also indicated an overall genotypic effect (F (1,20) = 4.539, P < .05) and a significant alteration of the crossing numbers at varying distances from the soma in Akt1 −/− mice (figure 3D).

Furthermore, as depicted in figures 3E and 3F, alteration of GABAergic, but not glutamatergic, inputs to striatal MSNs was found. Representative current traces of mEPSCs and mIPSC are shown in figures 3E-1 and 3E-2, respectively. No genotypic difference was found in the interevent interval (frequency) or the amplitude of the mEPSCs (figures 3E-2 and 3E-3). In contrast to glutamatergic inputs, GABAA receptor-mediated mIPSCs in striatal MSNs were significantly affected. A significantly lower interevent interval (ie, higher average frequency) was observed in Akt1 −/− mice, indicating an increase in the presynaptic release probability or the number of synaptic inputs (figure 3F-2). A significant reduction of the cumulative nature of the miniature amplitudes was also observed in Akt1 −/− mice, indicating that the overall levels of functional GABAA receptors on the postsynaptic membrane were altered (figure 3F-3). These findings suggest that the deficiency of Akt1 might affect inhibitory, but not excitatory, neurotransmission at both pre- and postsynaptic sites of striatal MSNs.

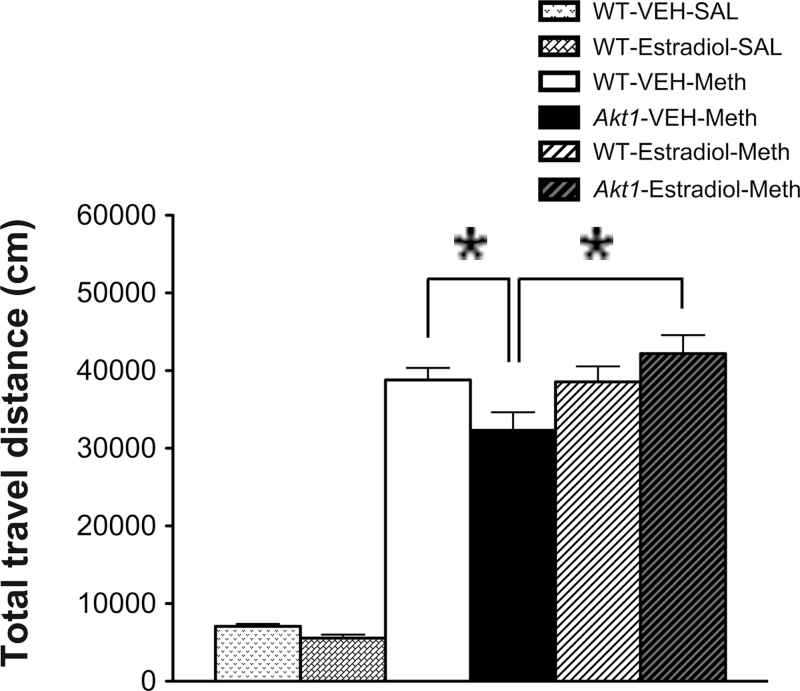

Experiment 4: Daily Injections of 17β-Estradiol Prevented the Reduction of Meth-Induced Hyperactivity in Male Akt1−/− Mice

As depicted in figure 4, there were significant differences among the 6 groups (F (5,67) = 93.715, P = .0001), and all Meth-injection groups displayed significant hyperlocomotion on the challenge day compared with the saline-injection groups. As reported previously, Akt1 deficiency resulted in the significant reduction of Meth-induced hyperlocomotion in Akt1 −/− mice (P = .008; WT-VEH-Meth group vs Akt1-VEH-Meth group). By contrast, daily injections of 17β-estradiol did not affect Meth-induced hyperlocomotion in WT mice (WT-VEH-Meth group vs WT-Estradiol-Meth group). However, compared with the Akt1-VEH-Meth group, such treatment significantly prevented the reduction of Meth-induced hyperlocomotion in the Akt1-Estradiol-Meth group (P = .0001).

Fig. 4.

Evaluation of the effect of 17β-estradiol on the prevention of the Meth-induced hyperlocomotion deficit in male Akt1 −/− mice. Total travel distance (mean + SEM cm) of the 6 treatment groups (n = 11–13 each) of male WT and Akt1 −/− mice that received 17β-estradiol/vehicle (s.c.) and Meth/saline (ip) injections are shown for the challenge day. *P < .05.

Discussion

The use of genetically modified mice that carry an alteration of the Akt1 gene as an experimental tool offers an alternative model to mimic the reduction of AKT1 in some schizophrenic patients1,16 and provides a feasible model to characterize the effect of Meth in Akt1-deficient mice. The sex-specific effect of Akt1 on the regulation of Meth-induced behavioral sensitization and striatal activity found in this study is of great interest. Our data consistently indicated that Akt1 deficiency dampens dopamine-dependent responses and that this phenomenon is evident in males only. In contrast, some sex-specific behavioral deficits were also found in drug-free, Akt1-deficient female mice.10 As mentioned previously, gender differences have been reported in both Meth use disorders8 and schizophrenia.7 The “estrogen protection hypothesis” has been proposed and indicates that estrogen might exert a neuroprotective effect against several disease models and human disorders, including schizophrenia and Meth use disorders. Our findings appear to recapitulate some of these sex differences in Akt1 −/− mice and support the involvement of AKT1 in the sex differences of these 2 disorders. Furthermore, numerous studies have demonstrated that estrogen exerts neuroprotective effects against ischemia and apoptosis via estrogen receptors and activation of insulin/PI3K/AKT pathway.39–42 In vitro studies using transient Akt1 transfection, Akt inhibitor, and dominant-negative Akt1 further revealed that Akt1 kinase activity is required for the upregulation of estrogen receptor α by modulating association of these receptors to the target gene promoters.43 The importance of AKT in the suppression of estrogen receptor α-mediated transcription and in estrogen-stimulated synaptogenesis was also reported.44,45 Similar to AKT1, accumulating studies have confirmed the importance of 17β-estradiol in regulating structural plasticity through direct or indirect effects on dendritic and axonal morphology,46 and the estrogen receptor α gene also exhibits a positive association with schizophrenia.12 Interestingly, in this study, the reduction of Meth-induced hyperlocomotion can be prevented by subchronic injections of 17β-estradiol, the most potent of the mammalian estrogenic steroids, in Akt1 −/− males. However, 17β-estradiol alone has no effect on the alteration of locomotion or Meth-induced hyperlocomotion in our male WT mice. These findings suggest that estrogen might play a role in the regulation of dopamine-dependent signaling cascade and Meth-induced behavioral sensitization in the absence of Akt1 in male mice. Thus, in addition to the above-mentioned estrogen-mediated neuroprotection by Akt1, the modulatory effect of estradiol on dopamine signaling could be independent of the AKT1 pathway. Estrogens might compensatively upregulate other dopamine signaling pathways (eg, cAMP/PKA/DARPP-32, MAPK, or CREB signaling) or other related genes through genomic regulations, as suggested previously,47,48 to enhance dopamine-dependent responses. Future research in this area would be timely and greatly worthwhile.

Additionally, the sex-specific role of Akt1 in the modulation of Meth was further confirmed by coinjections of Meth with a DRD2 antagonist and measures of Meth-induced striatal activity using microPET. Coinjections of Meth with raclopride, but not SCH23390, significantly dampened Meth-induced hyperlocomotion in WT males but was less effective in male Akt1 −/− mice, indicating the importance of Akt1 and DRD2 in the modulation of Meth-dependent hyperlocomotion in male mice. As described previously, compelling evidence from both human and mouse studies suggests that genetic variations in AKT1 or AKT1 protein have epistatic effects on the regulation of dopamine-dependent functions or drug effects.1,10,17,18 AKT was also reported to participate in the DRD2-dependent AKT-β-arrestin2-PP2A complex and to regulate the expression of dopamine-associated behaviors.19–21 Our data further highlight AKT1’s (rather than the other 2 isoforms) important role in the regulation of dopamine-dependent responses. However, the deficiency of Akt1 in male mice did not alter basal levels of neurotransmitters among the 5 brain areas we examined. The enhancement of norepinephrine release in the frontal cortex and midbrain of Akt1 −/− mice is somewhat unexpected. It could be due to the possibility of region-specific compensation in Akt1 −/− mice, as reported previously using in vivo microdialysis to reveal an increase in the basal level of extracellular dopamine in prefrontal cortex.17 Furthermore, our microPET data not only reconfirm the importance of Akt1 in the dopamine-dependent signaling cascade but also provide regional- and temporal-specific evidence to support the previously proposed AKT/GSK3-dependent, long-lasting wave of Meth-induced parallel responses in the striatum of mice.20 These findings suggest that the striatum is highly involved in the observed differences in Meth-treated males and imply that postsynaptic MSNs in the striatum might play an important role in the regulation of Akt1-related psychomotor functions in these mice.

Among the electrophysiological/morphological properties of striatal MSNs that we examined in this study, Akt1 −/− mice exhibited higher input resistance and lower rheobases compared with WT controls. As expected, MSNs in Akt1 −/− males were more excitable, and they generated action potentials easily than their WT controls. However, MSNs in both groups displayed similar firing patterns once the depolarizing currents exceed their rheobases. Additionally, it was reported that activation of AKT increased the number of postsynaptic GABAA receptors and receptor-mediated synaptic transmission.25 The reduction of the amplitude of mIPSCs in Akt1 −/− males further implied that the function of GABAA receptors was downregulated in their striatal MSNs and that there might be an imbalance of the excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs to MSNs in Akt1 −/− mice. Considering the intrinsic membrane properties and the measurement of miniature currents together, these alterations seem to exert similar effects and lead to an enhanced excitability of postsynaptic MSNs in Akt1-deficient mice. Furthermore, AKT has been found to be involved in several features of neurite outgrowth including elongation, branching, and caliber49 that may affect the electrophysiological properties of neurons. Indeed, neuromorphological alterations of GFP-labeled pyramidal neurons in Akt1 −/− mice have been reported previously in the medial prefrontal cortex17 and the auditory cortex.10 Our current data further revealed that striatal MSNs in Akt1 −/− males also had region-specific alterations. These neuromorphological changes might at least partially account for the observed alterations in electrophysiological properties and input resistances. Although we did not separately record D1-/D2-like receptors of MSNs in this study because these 2 subgroups are morphologically indistinguishable and mosaically distributed,50 the observed alternations in striatal MSNs are more likely to be related to the striatopallidal MSNs50,51 and express the D2-like receptors that reduce the output of MSNs.52–54

In conclusion, our data revealed a sex- and region-specific role of Akt1, a schizophrenia susceptibility gene, in the modulation of dopamine-dependent behavior and striatal neuronal activity. We also found that 17β-estradiol has a protective effect against the reduction of Meth-induced hyperlocomotion in Meth-sensitized Akt1 mutant males. As proposed by Kapur et al. in a revised theory based on the dopamine hypothesis of psychosis, striatal dopamine dysregulation could alter the appraisal of stimuli through a process of aberrant salience and eventually lead to psychosis.15,55,56 Accordingly, the alterations of the electrophysiological and neuromorphological properties of striatal MSNs in Akt1 mutant mice might be responsible for some psychomotor functions that we reported in this study and for those dopamine-related cognitive dysfunctions (eg, aberrant motivational salience and reward prediction error) that we reported recently.35 Our study highlights the importance of AKT1 in the dopamine-dependent response and sensitivity to Meth, which might, at least in part, account for the pathogenesis of Meth-induced psychosis and Meth abuse. Our findings also imply that the AKT1 deficiency could result in reduced Meth sensitivity and Meth-induced brain activity in male Meth users. Behavioral and physiological compensation might occur in these vulnerable individuals. The reduction could evoke higher doses or repeated use of Meth to overcome such deficit but lead to higher abuse potential or more severe Meth-induced psychosis state. In the future studies, many follow-up experiments can be carried out accordingly. Further exploration and confirmation of the roles of estrogen (or other sex hormones) in the regulation of Meth-induced hyperlocomotion or schizophrenia-like symptoms using Akt1 or other mutant mice is warranted too.

Funding

National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC99-2410-H-002-088-MY3, NSC98-2321-B-002-006); National Taiwan University (Neurobiology and Cognitive Science Center); National Taiwan University Hospital (101-042 to TJ Hwang and WS Lai).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at http://schizophre niabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Joseph Gogos, Dr Chen-Tung Yen, Dr Keng-Chen Liang, Dr Kai-Yuan Tzen, Dr Hai-Gwo Hwu, and Dr Tzung-Jeng Hwang for their valuable comments, support, and help with this study and the animal PET experiment. We also wish to thank all members in the Laboratory of Integrated Neuroscience and Ethology (the LINE) in the Department of Psychology, National Taiwan University.

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1. Emamian ES, Hall D, Birnbaum MJ, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA. Convergent evidence for impaired AKT1-GSK3beta signaling in schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2004; 36: 131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schwab SG, Wildenauer DB. Update on key previously proposed candidate genes for schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009; 22: 147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ikeda M, Iwata N, Suzuki T, et al. Positive association of AKT1 haplotype to Japanese methamphetamine use disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006; 9: 77–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bousman CA, Glatt SJ, Everall IP, Tsuang MT. Genetic association studies of methamphetamine use disorders: A systematic review and synthesis. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009; 150B: 1025–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yui K, Ikemoto S, Ishiguro T, Goto K. Studies of amphetamine or methamphetamine psychosis in Japan: relation of methamphetamine psychosis to schizophrenia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000; 914: 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aleman A, Kahn RS, Selten JP. Sex differences in the risk of schizophrenia: evidence from meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003; 60: 565–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McGrath J, Saha S, Welham J, El Saadi O, MacCauley C, Chant D. A systematic review of the incidence of schizophrenia: the distribution of rates and the influence of sex, urbanicity, migrant status and methodology. BMC Med. 2004; 2: 13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dluzen DE, Liu B. Gender differences in methamphetamine use and responses: a review. Gend Med. 2008; 5: 24–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Scott JC, Woods SP, Matt GE, et al. Neurocognitive effects of methamphetamine: a critical review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev. 2007; 17: 275–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen YW, Lai WS. Behavioral phenotyping of v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1-deficient mice reveals a sex-specific prepulse inhibition deficit in females that can be partially alleviated by glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitors but not by antipsychotics. Neuroscience. 2011; 174: 178–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Seeman MV. Psychopathology in women and men: focus on female hormones. Am J Psychiatry. 1997; 154: 1641–1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weickert CS, Miranda-Angulo AL, Wong J, et al. Variants in the estrogen receptor alpha gene and its mRNA contribute to risk for schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008; 17: 2293–2309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kulkarni J, de Castella A, Fitzgerald PB, et al. Estrogen in severe mental illness: a potential new treatment approach. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008; 65: 955–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kulkarni J, Riedel A, de Castella AR, et al. A clinical trial of adjunctive oestrogen treatment in women with schizophrenia. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2002; 5: 99–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kapur S, Mamo D. Half a century of antipsychotics and still a central role for dopamine D2 receptors. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003; 27: 1081–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao Z, Ksiezak-Reding H, Riggio S, Haroutunian V, Pasinetti GM. Insulin receptor deficits in schizophrenia and in cellular and animal models of insulin receptor dysfunction. Schizophr Res. 2006; 84: 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lai WS, Xu B, Westphal KG, et al. Akt1 deficiency affects neuronal morphology and predisposes to abnormalities in prefrontal cortex functioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006; 103: 16906–16911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tan HY, Nicodemus KK, Chen Q, et al. Genetic variation in AKT1 is linked to dopamine-associated prefrontal cortical structure and function in humans. J Clin Invest. 2008; 118: 2200–2208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beaulieu JM, Sotnikova TD, Marion S, Lefkowitz RJ, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. An Akt/beta-arrestin 2/PP2A signaling complex mediates dopaminergic neurotransmission and behavior. Cell. 2005; 122: 261–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beaulieu JM, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. The Akt-GSK-3 signaling cascade in the actions of dopamine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007; 28: 166–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beaulieu JM, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Akt/GSK3 signaling in the action of psychotropic drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009; 49: 327–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Joel D, Weiner I. The connections of the dopaminergic system with the striatum in rats and primates: an analysis with respect to the functional and compartmental organization of the striatum. Neuroscience. 2000; 96: 451–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Van den Heuvel DM, Pasterkamp RJ. Getting connected in the dopamine system. Prog Neurobiol. 2008; 85: 75–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bolam JP, Bergman H, Graybiel AM, et al. Microcircuits in the Striatum. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang Q, Liu L, Pei L, et al. Control of synaptic strength, a novel function of Akt. Neuron. 2003; 38: 915–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kalivas PW, Stewart J. Dopamine transmission in the initiation and expression of drug- and stress-induced sensitization of motor activity. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1991; 16: 223–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Robinson TE, Becker JB. Enduring changes in brain and behavior produced by chronic amphetamine administration: a review and evaluation of animal models of amphetamine psychosis. Brain Res. 1986; 396: 157–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lieberman JA, Kinon BJ, Loebel AD. Dopaminergic mechanisms in idiopathic and drug-induced psychoses. Schizophr Bull. 1990; 16: 97–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Iyo M, Bi Y, Hashimoto K, Tomitaka SI, Inada T, Fukui S. Does an increase of cyclic AMP prevent methamphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization in rats? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996; 801: 377–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Paulson PE, Robinson TE. Amphetamine-induced time-dependent sensitization of dopamine neurotransmission in the dorsal and ventral striatum: a microdialysis study in behaving rats. Synapse. 1995; 19: 56–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tsuchida K, Ujike H, Kanzaki A, Fujiwara Y, Akiyama K. Ontogeny of enhanced striatal dopamine release in rats with methamphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994; 47: 161–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cho H, Thorvaldsen JL, Chu Q, Feng F, Birnbaum MJ. Akt1/PKBalpha is required for normal growth but dispensable for maintenance of glucose homeostasis in mice. J Biol Chem. 2001; 276: 38349–38352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weinshenker D, Miller NS, Blizinsky K, Laughlin ML, Palmiter RD. Mice with chronic norepinephrine deficiency resemble amphetamine-sensitized animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002; 99: 13873–13877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ono Y, Lin HC, Tzen KY, et al. Active coping with stress suppresses glucose metabolism in the rat hypothalamus. Stress. 2012; 15: 207–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen YC, Chen YW, Hsu YF, et al. Akt1 deficiency modulates reward learning and reward prediction error in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2012; 11: 157–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jiang ZG, North RA. Membrane properties and synaptic responses of rat striatal neurones in vitro. J Physiol (Lond). 1991; 443: 533–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nisenbaum ES, Wilson CJ. Potassium currents responsible for inward and outward rectification in rat neostriatal spiny projection neurons. J Neurosci. 1995; 15: 4449–4463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. D’Astous M, Morissette M, Di Paolo T. Effect of estrogen receptor agonists treatment in MPTP mice: evidence of neuroprotection by an ER alpha agonist. Neuropharmacology. 2004; 47: 1180–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cimarosti H, Zamin LL, Frozza R, et al. Estradiol protects against oxygen and glucose deprivation in rat hippocampal organotypic cultures and activates Akt and inactivates GSK-3beta. Neurochem Res. 2005; 30: 191–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang R, Zhang QG, Han D, Xu J, Lü Q, Zhang GY. Inhibition of MLK3-MKK4/7-JNK1/2 pathway by Akt1 in exogenous estrogen-induced neuroprotection against transient global cerebral ischemia by a non-genomic mechanism in male rats. J Neurochem. 2006; 99: 1543–1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yu X, Rajala RV, McGinnis JF, et al. Involvement of insulin/phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signal pathway in 17 beta-estradiol-mediated neuroprotection. J Biol Chem. 2004; 279: 13086–13094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stoica GE, Franke TF, Moroni M, et al. Effect of estradiol on estrogen receptor-alpha gene expression and activity can be modulated by the ErbB2/PI 3-K/Akt pathway. Oncogene. 2003; 22: 7998–8011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Park S, Song J, Joe CO, Shin I. Akt stabilizes estrogen receptor alpha with the concomitant reduction in its transcriptional activity. Cell Signal. 2008; 20: 1368–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Akama KT, McEwen BS. Estrogen stimulates postsynaptic density-95 rapid protein synthesis via the Akt/protein kinase B pathway. J Neurosci. 2003; 23: 2333–2339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wong J, Woon HG, Weickert CS. Full length TrkB potentiates estrogen receptor alpha mediated transcription suggesting convergence of susceptibility pathways in schizophrenia. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011; 46: 67–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. de Lacalle S. Estrogen effects on neuronal morphology. Endocrine. 2006; 29: 185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jover-Mengual T, Zukin RS, Etgen AM. MAPK signaling is critical to estradiol protection of CA1 neurons in global ischemia. Endocrinology. 2007; 148: 1131–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhao L, Brinton RD. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta differentially regulate intracellular Ca(2+) dynamics leading to ERK phosphorylation and estrogen neuroprotection in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2007; 1172: 48–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Read DE, Gorman AM. Involvement of Akt in neurite outgrowth. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009; 66: 2975–2984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lobo MK, Karsten SL, Gray M, Geschwind DH, Yang XW. FACS-array profiling of striatal projection neuron subtypes in juvenile and adult mouse brains. Nat Neurosci. 2006; 9: 443–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gerfen CR, Young WS., 3rd Distribution of striatonigral and striatopallidal peptidergic neurons in both patch and matrix compartments: an in situ hybridization histochemistry and fluorescent retrograde tracing study. Brain Res. 1988; 460: 161–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Calabresi P, Picconi B, Tozzi A, Di Filippo M. Dopamine-mediated regulation of corticostriatal synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2007; 30: 211–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Surmeier DJ, Ding J, Day M, Wang Z, Shen W. D1 and D2 dopamine-receptor modulation of striatal glutamatergic signaling in striatal medium spiny neurons. Trends Neurosci. 2007; 30: 228–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kreitzer AC, Malenka RC. Striatal plasticity and basal ganglia circuit function. Neuron. 2008; 60: 543–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kapur S, Mizrahi R, Li M. From dopamine to salience to psychosis–linking biology, pharmacology and phenomenology of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2005; 79: 59–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Howes OD, Kapur S. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: version III–the final common pathway. Schizophr Bull. 2009; 35: 549–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.