Abstract

Purpose

This study computed the risk of clinically silent adnexal neoplasia in women with germ-line BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations (BRCAm+) and determined recurrence risk.

Methods

We analyzed risk reduction salpingo-oophorectomies (RRSOs) from 349 BRCAm+ women processed by the SEE-FIM protocol and addressed recurrence rates for 29 neoplasms from three institutions.

Results

Nineteen neoplasms (5.4%) were identified at one institution, 9.2% of BRCA1 and 3.4% of BRCA2 mutation-positive women. Fourteen had a high-grade tubal intraepithelial neoplasm (HGTIN, 74%). Mean age (54.4) was higher than the BRCAm+ cohort without neoplasia (47.8) and frequency increased with age (p<0.001). Twenty-nine BRCA m+ patients with neoplasia from three institutions were followed for a median of 5 years (1–8 yrs.). One of 11 with HGTIN alone (9%) recurred at 4 years, in contrast to 3 of 18 with invasion or involvement of other sites (16.7%). All but two, are currently alive. Among the 29 patients in the three institution cohort, mean ages for HGTIN and advanced disease were 49.2 and 57.7 (p = 0.027).

Conclusions

Adnexal neoplasia is present in 5–6% of RRSOs, is more common in women with BRCA1 mutations, and recurs in 9% of women with HGTIN alone. The lag in time from diagnosis of the HGTIN to pelvic recurrence (4 years) and differences in mean age between HGTIN and advanced disease (8.5 years) suggest an interval of several years from the onset of HGTIN until pelvic cancer develops. However, some neoplasms occur in the absence of HGTIN.

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer related deaths in women in the United States, with approximately 22,000 new cases and 14,000 deaths annually.1 High-grade carcinomas - mostly serous type - have the worst outcome. They typically present in late stage, seeding the peritoneal cavity and metastasizing early in the disease course. 2

The anatomic origin of high grade serous carcinoma has been ascribed both to the ovarian surface as well as the distal fallopian tube, supported by the presence of high-grade serous tubal intraepithelial neoplasia (HGTIN), also termed serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (or STIC) in over 40% of women with disseminated high grade serous carcinoma.3 Identification of HGTIN or early tubal carcinoma in risk reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) specimens of asymptomatic women with presumed germ-line mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes (BRCAm+) further supports a tubal origin. 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 9, 10 Moreover, "latent" precursors with mutations in the p53 gene, known as “p53 signatures,” are commonly found in the fallopian tube epithelium and have been shown to be genetically linked to some high-grade serous carcinomas.11

RRSO is routinely offered to BRCAm+ patients or those with a strong personal or family history of breast and ovarian cancers or a family history of ovarian cancer alone. Unsuspected carcinomas have been reported in the fallopian tubes or ovaries of these women in between 2% and 17%, more precise estimates following the widespread adoption of the SEE-FIM protocol for more careful examination of the distal tube, including the fimbriae.4, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15 The clinical outcome of these small, clinically unsuspected neoplasms of the fallopian tube has not to date been characterized in great detail, owing to their relatively low frequency and non-uniform sampling of fallopian tubes. As a result, management of these patients and their prognosis has been uncertain.

A single study in 2004 reported one recurrence in a patient with a BRCA1 mutation among four patients undergoing RRSO.16 Two recent studies with larger numbers reported recurrence rates for HGTIN alone at 0 and 7%.17, 18 Our institution began using the SEE-FIM protocol to evaluate RRSO specimens in 2005 for BRCAm+ women, providing up to eight years of clinical followup.5 This population provides an opportunity to study both the detection frequency and longer term outcome of clinically unsuspected adnexal neoplasia in this unique population.

METHODS

This study was approved by the human investigation committees at Brigham and Women's Hospital, the University of Michigan Medical School and the Pacific Ovarian Cancer Research Consortium (POCRC). The material for the two major analyses was derived from two distinct clinical sources. The first analysis explored the frequency of neoplasia in a series of consecutive RRSOs conducted at Brigham and Women's Hospital and the Dana Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI). The second pooled high-grade TINs or carcinomas that were diagnosed following RRSO at BWH/DFCI, POCRC and University of Michigan and ascertained the risk of a pelvic cancer outcome (www.pointproject.org). All were reviewed by a second observer (CPC) to verify the diagnosis. For this study, cases were limited to high grade serous or endometrioid neoplasms detected in asymptomatic women that were small or microscopic and were tubal, ovarian or unclear in their origin. Histologic sections and p53 immunostains of representative early carcinomas with and without associated spread were reviewed. The term HGTIN in this study connotes a high-grade non-invasive serous tubal intraepithelial neoplasm unless otherwise specified. Histologic criteria for the diagnosis of HGTIN have been detailed previously, consisting of a combination of marked nuclear atypia and some loss of cell polarity, typically accompanied by an increased proliferative index and either strong or absent (due to a deletion mutation) immuno-positivity for p53. In essence, HGTIN corresponded to serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas as described previously.2,3

Frequency and clinicopathologic features of early carcinoma in patients with BRCA gene mutations

The case files of the Women’s and Perinatal Division in the Department of Pathology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital were searched for terms containing the sequence “BRCA” received between January 1, 2005 and February 15, 2013. From this data set, cases in which ovarian or tubal carcinoma was suspected preoperatively based on clinical, radiographic, or laboratory data were excluded. Although no standard pre-operative testing was performed, the stated impressions took into account standard imaging studies along with physical exam findings, and prior pathologic diagnoses when relevant. CA125 values were not obtained as part of the pre-operative management of patients in this cohort. Asymptomatic BRCAm+ cases, including cases in which carcinoma was identified during or after surgery, were included. The clinic records of each case were then reviewed for evidence corroborating a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation.

RRSOs were entirely submitted for microscopic examination according to the SEE-FIM protocol previously described.5 Clinically unsuspected carcinomas were divided into three categories: Group I were cases with HGTIN alone; Group II had HGTIN and evidence of advanced disease, including ovarian/serosal surfaces and positive peritoneal cytology; Group III had the latter findings without evidence of HGTIN.

Age was recorded for all and the median age of patients with early carcinoma was compared to the median age of patients without disease using an independent samples two-tailed t-test analysis. The proportion of patients with carcinoma at each year of age was calculated and used in a linear regression analysis to determine the correlation between age at time of RRSO and risk of early carcinoma.

Clinical outcomes of early carcinoma

The cohort of patients with neoplasia detected in RRSO specimens from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, POCRC, and University of Michigan Medical School, were identified. Patients were followed for signs of recurrent disease at the discretion of the managing physician using standard clinical, imaging, and laboratory (CA-125) signs. Recurrence was defined either by a direct cytologic or histologic diagnosis or by two consecutively rising CA-125 values above the patient’s established baseline levels.

RESULTS

RRSO specimens from patients with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations

Frequency of neoplasia

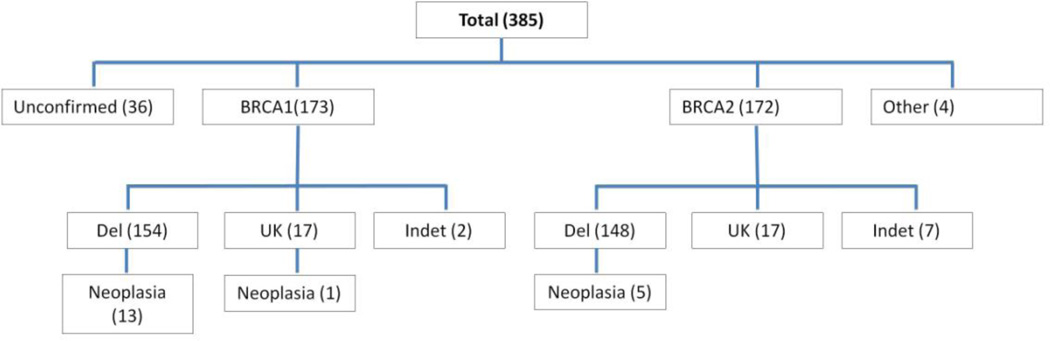

The initial results returned 452 reports with the term “BRCA” in the pathology report clinical history. After excluding cases of symptomatic malignancy, 385 were eligible for further analysis from a single major academic medical center (BWH) from January 2005 to February 2013. All but 3 were bilateral salpingo-oophorectomies. Within this group are 122 cases (and 7 early cancers) that have been previously reported.12 Figure 1 summarizes the breakdown of cases. In 36 a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation was not corroborated in the clinical record. In 345, a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation was specified in the clinical record; 34 were documented in clinical notes alone and 311 provided in addition a sequence report from Myriad Genetics. In four others, mutations in both genes or unspecified BRCA mutations were reported in the clinic notes. Cases specified as BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation positive included those with a documented deleterious mutation (del+) or mutation of uncertain significance (del-) based on sequence data, and BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation without further information (UK) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation status in the BWH cohort.

A total of 385 patients were designated as having a BRCA gene mutation on the pathology requisition submitted at the time of RRSO. Subsequent chart review revealed documented mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, or both (classified as “other”) in 349, whereas 36 cases were not confirmed. The nature of the mutations (del = known deleterious, UK = exact mutation unknown after chart review, indet = effect of mutation indeterminate) and frequency of neoplasia in each category are shown.

Mean ages for all of the 173 BRCA1 and 172 BRCA2 mutation-positive cases were 46.4 and 48.7 years respectively (p = 0.024). Overall, neoplasia was identified in 19 of 349 (5.4%) cases with any record of mutation and 18 of 313 (5.8%) cases with a documented deleterious mutation in BRCA1, BRCA2 or both. Neoplasia was discovered in 13/154 (9.2%) and 5/148 (3.4%) cases with documented deleterious mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 respectively (p = 0.09). Mean ages for patients with neoplasia in the two groups were 52.8 and 58.4 respectively (p =.32).

Histologic findings in unsuspected neoplasms detected at or following RRSO

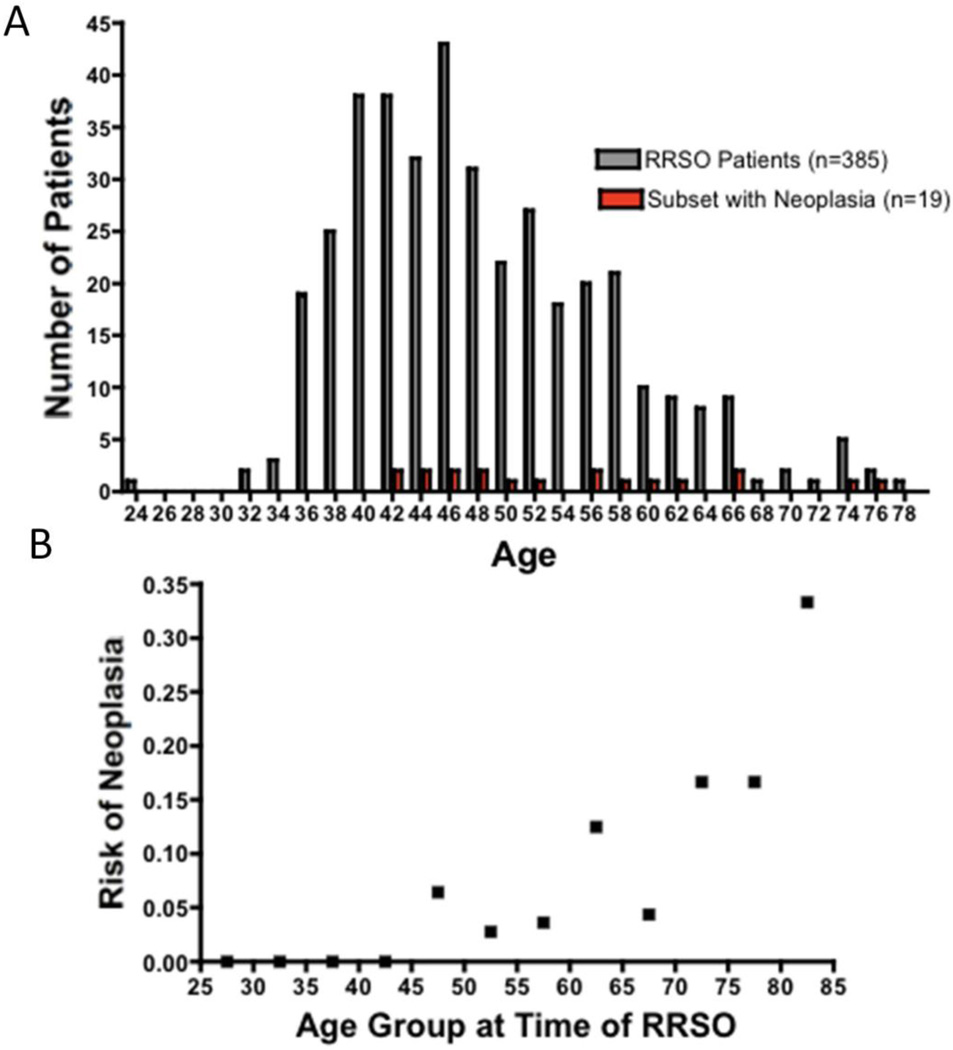

As shown in Figures 2A and 2B, patients with neoplasia were significantly older than patients without evidence of disease (median age of patients with neoplasia 51, mean 54.4; range 41–76, p=0.0009). Logistic regression analysis revealed a significant relationship between age at time of surgery and likelihood of an unsuspected carcinoma (p<0.001).

Figure 2. Age distribution of patients undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and patients with neoplasia.

A. Histogram showing ages for all patients undergoing risk-reducing salpingooophorectomy at BWH (grey) and the subset of patients with neoplasia (red). Patients with neoplasia were significantly older than patients without evidence of disease (p=0.0009). B. Age-related risk of unsuspected neoplasia at RRSO. Patients were grouped into 5 year age bins and the proportion of cases positive for neoplasia was plotted against age. Logistic regression analysis demonstrated a significant relationship between age at time of surgery and likelihood of an unsuspected neoplasia (p<0.001).

Thirteen of 19 cases had serous HGTIN and another endometrioid HGTIN for a total of 74% with evidence of an origin in the tubal mucosa. BRCA1 germ-line mutations were found in 14 of 19 (74%) overall, and 5 of 6 in Group I, 7 of 9 in Group II and 3 of 5 in Group III.

Mean age at time of diagnosis was 48.2 years for 6 cases with HGTIN alone 58.1 years for 7 cases with HGTIN and peritoneal involvement and 62.2 years for tumors without HGTIN (two-tailed t-test comparing cases with HGTIN alone to more advanced lesions, p=0.63).

Clinical outcomes of early tubal-ovarian carcinoma: retrospective experiences from three academic centers

To estimate the risk of recurrence following RRSO, 29 patients with BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutations with unsuspected neoplasia identified in RRSO specimens from three institutions were followed. Median follow-up was 5 years; (range <1 year to 8 years). The cases were subdivided into Groups I (11), II (12) and III (6). Two of 11 in Group I received chemotherapy versus all in Groups II and III. Mean ages in this multi-institutional data set for Groups I, II and III were 49.2, 56.9, and 61.0 years respectively. The differences in mean age between group I and II and I and III approached statistical significance (p = 0.052 and 0.064, t-test) and patients with HGTIN alone (group I) were significantly younger than those with more advanced disease (groups II and III; p = 0.027).

Twelve patients with invasive or more advanced carcinoma underwent a second staging laparoscopy, some including lymphadenectomy and omentectomy. Chemotherapy consisted of platinum and paclitaxel based combinations in all cases with all patients receiving intravenous therapy and one patient with a serosal metastasis documented at time of surgery receiving intraperitoneal therapy. One patient who recurred subsequently received gemcitabine for the recurrence. Two patients (both without evidence of early spread) have died of unrelated causes. No deaths have been directly attributable to adnexal malignancies.

A recurrence was observed in 1 of 11 in Group I (9.1%), 2 of 12 in Group II (16.7%) and 1 of 6 in Group III (16.7%). The recurrence in the patient with HGTIN alone was presumptive, based on ascites and increasing CA125, but no tissue diagnosis. Recurrence developed at 4 years for the case in Group I, and 5, 5, and 6 years for the cases in Groups II and III. There was no significant association between age and risk of recurrence (logistic regression analysis p =.06). No recurrences developed within the followup period in treated patients with microscopic serosal or ovarian metastases or peritoneal cytology in the absence of gross metastatic disease.

DISCUSSION

This study addresses three questions concerning ovarian cancer in BRCAm+ women: 1) Relationship of BRCA status to frequency of asymptomatic disease, 2) frequency of disease in RRSOs and 3) Risk of recurrence on followup. Estimates of occult neoplasia in RRSOs range from 2 to 17 per cent.4, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15, 18 In 2005, the SEE-FIM protocol was instituted at Brigham and Women's Hospital and specified more thorough sectioning of the fimbriated end to increase the amount of surface area evaluated in the fimbriated end.5 Since then, 100% of every fimbria has been examined in this manner in BRCAm+ women, including the remainder of the tube, excepting rare instances when a segment in the proximal one-third was retained for research.

The overall frequency of early neoplasia in this population ranged from 5.4% (for any record of mutation) to 5.8% (deleterious mutations only). This is similar to a prior study by Callahan et al from this institution that identified 7 cancers in 122 consecutive cases (5.7%).12 As shown in Figure 2, the frequency of cases in which neoplasia was detected increased significantly as a function of age. This indicates that the age of the cohort could influence the detection rate. A similar size study of women with a somewhat younger mean age (44) reported occult cancers in 8 of 360 (2.2%), including 6 HGTINs.19 Another variable that might influence detection and age of presentation is BRCA mutation status. In this study both the population and neoplasms associated with BRCA1 mutations were younger than the BRCA2 mutation positive group. These differences were not highly significant; however, BRCA1 mutation-positive women with symptomatic high grade pelvic carcinoma are significantly younger than their BRCA2 mutation-positive counterparts (Meserve et al, unpublished). Evidence thus suggests that BRCA1 mutation-positive individuals may be more susceptible and at a younger age, in keeping the higher overall risk of malignancy and adverse outcome in this subset.20, 21

BRCAm+ women who have undergone a RRSO with normal pathology have a reported 4–5 per cent risk of a pelvic serous cancer on follow-up, an approximately 4–9 fold greater risk than the general population.22 Going forward, this risk will likely be revised downward with the widespread adoption of protocols to thoroughly examine the distal fallopian tube. Such protocols should lower the miss rate for microscopic tubal neoplasia (HGTIN) that could later recur, but may not address other potential sources of disease .5, 8 Irrespective of site of origin, the risk of later recurrence when carcinoma is discovered is substantial. Powell et al noted a recurrence rate of 47% for cases with invasive carcinoma and in this study 17% (3 of 18) cases with invasion more advanced disease recurred.23 These individuals invariably are counseled to receive adjunctive therapy. The principal question is how to manage non-invasive neoplasia (HGTIN). One of 17 (5.8) % high-grade intraepithelial neoplasms in the study by Powell et al recurred at 43 months. In the current study 1 of 11 (9%) cases with HGTIN alone recurred (Table 2). If the data from these two studies are combined, the risk of recurrence following invasion or other evidence of spread (11 of 32) is significantly higher than that for intraepithelial neoplasia (2 of 26; p=.024 by Fishers exact test). Wethington et al noted no recurrences in 12 HGTINs over a median of 28 months.18 This supports aggressive management when the tumor has spread or advanced, but does not support prophylactic chemotherapy for HGTIN alone, pending additional data that would clarify which patients with HGTIN were more likely to have a recurrence.

TABLE 2.

Pathologic Features and Clinical Outcomes of Incidental Carcinomas Detected at RRSO from 3 Institutions

| Age* | Institut ion |

Pathology | Chemotherapy** | Recurrence | Current Status | Years of Followup |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | ||||||

| 41 | BWH | HGTIN | No | No | Alive | 5 |

| 41 | BWH | HGTIN | No | No | Alive | 1 |

| 44 | BWH | HGTIN | Yes | No | Alive | 8 |

| 46 | BWH | HGTIN | No | Yes - positive ascites cytology and elevated CA-125; 4 yrs after BSO | Alive | 6 |

| 51 | BWH | HGTIN | No | No | Lost to followup 2009 | <1 |

| 53 | FHCRC | HGTIN | NO | NO | Alive | 3 |

| 49 | UMICH | HGTIN | No | No | Alive | 2 |

| 37 | UMICH | HGTIN | No | No | Alive | 2 |

| 53 | FHCRC | HGTIN | No | No | followup 2011 | 7 |

| 60 | BWH | HGTIN | Yes | No | Alive | 7 |

| 66 | BWH | HGTIN | Yes (2 cycles) | No | Alive | 8 |

| Group II | ||||||

| 57 | BWH | HGTIN and focal invasive tubal carcinoma | Yes | No | Expired 2010 (metastatic breast cancer) | 2 |

| 57 | FHCRC | HGTIN and invasive tubal carcinoma | Yes | No | Alive | 6 |

| 67 | FHCRC | HGTIN and invasive tubal carcinoma | Yes (3 cycles) | Yes – elevated CA-125; 5 yrs after BSO | Alive | 6 |

| 60 | FHCRC | HGTIN (2 foci) and metastatic carcinoma on ovarian surface | Yes | No | Alive | 5 |

| 49 | UMICH | HGTIN with associated invasive carcinoma and positive peritoneal cytology | Yes | No | Alive | <1 |

| 43 | BWH | HGTIN and positive peritoneal cytology | Yes | No | Alive | 8 |

| 48 | BWH | HGTIN and metastatic carcinoma on ovarian surface, positive peritoneal cytology | Yes | No | Alive | 4 |

| 56 | BWH | HGTIN and metastatic carcinoma on ovarian surface | Yes | No | Alive | <1 |

| 56 | BWH | HGTIN and metastatic carcinoma on ovarian surface | Yes | No | Alive | 1 |

| 65 | BWH | HGTIN and metastatic carcinoma on ovarian surface, positive peritoneal cytology | Yes | No | Lost to followup 2008 | 1 |

| 76 | BWH | HGTIN with associated invasive carcinoma and Multiple serosal metastases, positive peritoneal cytology | Yes | Yes - elevated ca-125 and tissue diagnosis at 6 yrs | Alive | 8 |

| 49 | BWH | Endometrioid adenocarcinom a (moderately differentiated) involving fallopian tube and metastatic carcinoma on ovarian surface | Yes | No | Alive | 6 |

| Group III | ||||||

| 73 | BWH | Invasive serous carcinoma, involving fimbriae | Yes | Yes - elevated CA-125; 5 yrs after BSO | Alive | 6 |

| 62 | BWH | Endometrioid adenocarcinom a (grade 2/3), involving fimbriae | Yes (1 cycle) | No | Alive | 8 |

| 50 | FHCRC | Invasive carcinoma, bilateral fallopian tubes | Yes | No | Alive | 6 |

| 74 | FHCRC | Invasive tubal Carcinoma | Yes (3 cycles) | No | Expired 2008 (pneumonia) | <1 |

| 46 | BWH | Endometrioid adenocarcinom a (grade 3 of 3) involving ovarian surface and positive peritoneal cytology, abdominal wall nodule | Yes | No | Alive | 5 |

| 51 | BWH | High grade serous carcinoma, involving ovarian surface and positive peritoneal cytology | Yes | No | Alive | 4 |

Age at time of prophylactic BSO

All chemotherapy patients received 6 courses unless otherwise stated

The BRCAm+ population plays an important role in efforts to devise models of frequency of HGTIN and transit time from HGTIN to serous cancer. They bear on both efforts to estimate the effectiveness of prophylactic salpingectomy in preventing this disease and screening efforts to interrupt potentially curative stages of neoplasia. RRSO provides the unique opportunity to detect disease early and crudely estimate the timing of progression from early (such as HGTIN) to advanced disease by either following women with HGTIN or comparing the mean ages of patients at different stages of disease. Several confounders are unavoidable. The decisions of when to screen for BRCA mutations and when to perform RRSO infuence the age at which an asymptomatic neoplasm will be detected. The timing of testing is patient dependent and often influenced by concerns raised with the prior detection of breast cancer. Moreover, BRCA2 mutation positive cohorts with or without neoplasia tend to be slightly older than their BRCA1 counterparts, further confounding the interpretation of age differences.

Three findings in this study and others suggest that there might be a substantial interval from the onset of HGTIN to either asymptomatic or symptomatic spread. First, most HGTINs are not associated with recurrences, indicating the acquisition of metastatic potential takes time after a HGTIN emerges. Second, the mean ages for patients with localized HGTIN vs HGTIN with advanced disease were 49.2 and 56.9 years, a difference that approached significance. Third, the lag time from discovery of a HGTIN to (presumed) recurrence was 43 and 48 months in the two recurrences recorded this study and that of Powell et al. The first two observations imply that the tubal serous carcinogenic pathway conceivably might be interrupted by detecting pre-metastatic neoplasia, the removal of which would prevent subsequent disease.

Although the above findings merit further studies to determine their relevance to serous cancer prevention, an equally compelling question remains to be answered, which is a paradox between the frequency of HGTIN in RRSOs vs cases of symptomatic, advanced high-grade serous carcinoma. Estimates of associated HGTIN in unselected women with symptomatic high grade cancer range from 19 to 59 percent, a distinct contrast to the rate of 74% in the asymptomatic population in this study. This implies that many cancers are not initiated in recognizable HGTINs.24 Interestingly, Powell et al noted that the mean age of their cases with invasion was significantly younger than those with intraepithelial neoplasia only (50 vs. 55, p= 0.04).23 Whether these discrepancies are a function of demographics, tissue sampling, different transit times, or variable pathways and organs (peritoneum, ovary etc) involved in the pathogenesis of pelvic serous cancer remains to be determined. However, it leaves open the possibility that more than one carcinogenic pathway is involved in the development of high grade serous carcinoma, including one that manifests rapidly and not clearly of tubal origin. In a study of registry data of 63 BRCAm+ cancers, Piek et al noted only 6% were reported as tubal in origin. This figure is a likely underestimation of tubal involvement, but nonetheless contrasts sharply with the detection rate in asymptomatic women.25 In a histologic analysis of tubes of symptomatic BRCAm+ women with carcinoma using the SEE-FIM protocol, we have found STIC in less than 40% of cases (Meserve, Schulte and Crum, unpublished). Thus, more thorough analysis of high-grade serous cancers in symptomatic BRCAm+ women is needed to shed light on this question. 24

In summary, this study has shown a detection rate of 5.4% for early adnexal cancer in BRCAm+ women undergoing RRSO and a recurrence rates of from 9–17% over 5 years depending on extent at the time of RRSO. There is a low-rate of recurrence overall following chemotherapy for local spread and an absence of cancer-related deaths in the first five years following diagnosis. At this point there is no compelling justification for prophylactic chemotherapy in cases with TIC alone. The precise lag time from localized to more advanced disease remains unclear. Alternate pathways to neoplasia should be excluded by meticulous pathologic studies of advanced high grade serous carcinomas in these women.

TABLE 1.

Genetic, Pathologic, and Clinical Features of Unsuspected Carcinomas Detected in BWH patients at RRSO

| Age* | Gene with Mutation |

BRCA Mutation | Fallopian Tube Involvement |

Ovarian Surface Involvement |

Other Peritoneal Involvement |

Peritoneal Washing Cytology |

Subsequent Surgical Staging |

FIGO Stage |

Other Malignancies |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | ||||||||||

| 41 | BRCA1 | 243T>C | HGTIN | None | None | Negative | Yes | 0 | None | |

| 41 | BRCA1 | 3717C>T | HGTIN | None | None | Negative | Yes | 0 | None | |

| 44 | BRCA1 | 1294del40 | HGTIN | None | None | Negative | No | 0 | Breast | |

| 46 | BRCA1 | Not available | HGTIN | None | None | Negative | No | 0 | Breast | |

| 51 | BRCA1 | 4184del4 | HGTIN | None | None | Negative | No | 0 | None | |

| 66 | BRCA2 | 5301insA | HGTIN | None | None | Negative | Yes | 0 | None | |

| Group II | ||||||||||

| 43 | BRCA2 | W2586X | HGTIN | None | None | Positive | Yes | 1c | Breast | |

| 57 | BRCA1 | 943ins10 | HGTIN with associated invasive serous carcinoma | None | None | Negative | Yes | 1a | Breast | |

| 60 | BRCA1 | 4794G>A | HGTIN with associated invasive serous carcinoma | None | None | Negative | No | 1a | Breast (DCIS) | |

| 56 | BRCA1 | 4154delA | HGTIN | Bilateral (multiple foci) | None | Negative | Yes | 1c* | Breast | |

| 46 | BRCA1 | 2953delGTAinsC | Endometrioid TIN | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | Anterior abdominal wall implant | Positive | Yes | 2c/3a*† | Breast | |

| 65 | BRCA1 | 2798del4 | HGTIN | Present on contralateral surface, ipsilateral surface covered by thin pseudocapsule | None | Positive | No (full staging performed with RRSO after frozen section diagnosis) | 2c* | None | |

| 65 | BRCA1 | 2798del4 | HGTIN | Present on contralateral surface, ipsilateral surface covered by thin pseudocapsule | None | Positive | No (full staging performed with RRSO after frozen section diagnosis) | 2c* | None | |

| 56 | BRCA2 | L2653P | HGTIN | Ipsilateral | None | Suspicious for malignancy | Yes | 2a | None | |

| 48 | BRCA1 | Exon 13 ins 6 kb | HGTIN | Bilateral | None | Positive | Yes | 2c | None | |

| Group III | ||||||||||

| 62 | BRCA1 | 187delAG | Invasive endometrioid adenocarcinoma (grade 2/3), involving fimbriae | None | None | Atypical, favor reactive mesothelial cells | Yes | 1a | Breast | |

| 73 | BRCA1 | 2953delGTAinsC | Invasive serous carcinoma, involving fimbriae | None | None | Negative | No | 1a | Breast | |

| 49 | BRCA1 | Q1240X | Moderately differentiated (likely endometrioid) adenocarcinoma | Ipsilateral | None | Negative | Yes | 2a | None | |

| 76 | BRCA2 | 6174delT | Bilateral serous carcinoma involving fimbriae | None | Gross tumor seen on omentum and multiple other peritoneal surfaces | Positive | No (full staging performed with RRSO after frozen section diagnosis) | 3b | Pancreatic | |

| 51 | BRCA2 | 3331G>T | None | Bilateral serous carcinoma | None | Positive | Yes | 1c* | None | |

Cases staged as primary ovarian carcinoma

A single focus of microscopic disease was found in the pelvis on the anterior abdominal wall.

Adnexal neoplasia was found in ~5% of risk reduction surgeries for BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations

Recurrences developed in from 9–17% over a median of 5 years followup.

There were no ovarian cancer-related deaths at 5 years.

Acknowledgements

Supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (NCI P50 CA083636 to NU)( 1R21CA124688-01A1 to CPC) and Department of Defense (W81XWH-10-1-0289 to CPC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cancer Facts and Figures. Atlanta, Georgia, USA: American Cancer Society; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlson J, Roh MH, Chang MC, Crum CP. Recent advances in the understanding of the pathogenesis of serous carcinoma: the concept of low-and high-grade disease and the role of the fallopian tube. Diagnostic histopathology. 2008;14(8):352–365. doi: 10.1016/j.mpdhp.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kindelberger DW, Lee Y, Miron A, Hirsch MS, Feltmate C, Medeiros F, et al. Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: Evidence for a causal relationship. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2007;31(2):161–169. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213335.40358.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finch A, Shaw P, Rosen B, Murphy J, Narod SA, Colgan TJ. Clinical and pathologic findings of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomies in 159 BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Gynecologic oncology. 2006;100(1):58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medeiros F, Muto MG, Lee Y, Elvin JA, Callahan MJ, Feltmate C, et al. The tubal fimbria is a preferred site for early adenocarcinoma in women with familial ovarian cancer syndrome. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2006;30(2):230–236. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000180854.28831.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose PG, Shrigley R, Wiesner GL. Germline BRCA2 mutation in a patient with fallopian tube carcinoma: a case report. Gynecologic oncology. 2000;77(2):319–320. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paley PJ, Swisher EM, Garcia RL, Agoff SN, Greer BE, Peters KL, et al. Occult cancer of the fallopian tube in BRCA-1 germline mutation carriers at prophylactic oophorectomy: a case for recommending hysterectomy at surgical prophylaxis. Gynecologic oncology. 2001;80(2):176–180. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.6071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powell CB, Kenley E, Chen LM, Crawford B, McLennan J, Zaloudek C, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA mutation carriers: role of serial sectioning in the detection of occult malignancy. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(1):127–132. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werness BA, Ramus SJ, Whittemore AS, Garlinghouse-Jones K, Oakley-Girvan I, Dicioccio RA, et al. Histopathology of familial ovarian tumors in women from families with and without germline BRCA1 mutations. Human pathology. 2000;31(11):1420–1424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werness BA, Ramus SJ, DiCioccio RA, Whittemore AS, Garlinghouse-Jones K, Oakley-Girvan I, et al. Histopathology, FIGO stage, and BRCA mutation status of ovarian cancers from the Gilda Radner Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry. International journal of gynecological pathology : official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists. 2004;23(1):29–34. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000101083.35393.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee Y, Miron A, Drapkin R, Nucci MR, Medeiros F, Saleemuddin A, et al. A candidate precursor to serous carcinoma that originates in the distal fallopian tube. The Journal of pathology. 2007;211(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/path.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callahan MJ, Crum CP, Medeiros F, Kindelberger DW, Elvin JA, Garber JE, et al. Primary fallopian tube malignancies in BRCA-positive women undergoing surgery for ovarian cancer risk reduction. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(25):3985–3990. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leeper K, Garcia R, Swisher E, Goff B, Greer B, Paley P. Pathologic findings in prophylactic oophorectomy specimens in high-risk women. Gynecologic oncology. 2002;87(1):52–56. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mingels MJ, Roelofsen T, van der Laak JA, de Hullu JA, van Ham MA, Massuger LF, et al. Tubal epithelial lesions in salpingo-oophorectomy specimens of BRCA-mutation carriers and controls. Gynecologic oncology. 2012;127(1):88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manchanda R, Abdelraheim A, Johnson M, Rosenthal AN, Benjamin E, Brunell C, et al. Outcome of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA carriers and women of unknown mutation status. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2011;118(7):814–824. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.02920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agoff SN, Garcia RL, Goff B, Swisher E. Follow-up of in situ and early-stage fallopian tube carcinoma in patients undergoing prophylactic surgery for proven or suspected BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 mutations. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2004;28(8):1112–1114. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000131554.05732.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bijron JG, Seldenrijk CA, Zweemer RP, Lange JG, Verheijen RH, van Diest PJ. Fallopian Tube Intraluminal Tumor Spread From Noninvasive Precursor Lesions: A Novel Metastatic Route in Early Pelvic Carcinogenesis. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2013;37(8):1123–1130. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318282da7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wethington SL, Park KJ, Soslow RA, Kauff ND, Brown CL, Dao F, et al. Clinical Outcome of Isolated Serous Tubal Intraepithelial Carcinomas (STIC) International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society. 2013;23(9):1603–1611. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182a80ac8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reitsma W, de Bock GH, Oosterwijk JC, Bart J, Hollema H, Mourits MJ. Support of the 'fallopian tube hypothesis' in a prospective series of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy specimens. European journal of cancer. 2013;49(1):132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu J, Cristea MC, Frankel P, Neuhausen SL, Steele L, Engelstaedter V, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of BRCA-associated ovarian cancer: genotype and survival. Cancer genetics. 2012;205(1–2):34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hyman DM, Zhou Q, Iasonos A, Grisham RN, Arnold AG, Phillips MF, et al. Improved survival for BRCA2-associated serous ovarian cancer compared with both BRCA-negative and BRCA1-associated serous ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2012;118(15):3703–3709. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finch A, Beiner M, Lubinski J, Lynch HT, Moller P, Rosen B, et al. Salpingooophorectomy and the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancers in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;296(2):185–192. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powell CB, Swisher EM, Cass I, McLennan J, Norquist B, Garcia RL, et al. Long term follow up of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers with unsuspected neoplasia identified at risk reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. Gynecologic oncology. 2013;129(2):364–371. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crum C, Herfs M, Ning G, Bijron J, Howitt B, Jimenez C, et al. Through the glass darkly: intraepithelial neoplasia, top-down differentiation and the road to ovarian cancer. J Pathol. 2013 doi: 10.1002/path.4263. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piek JM, Torrenga B, Hermsen B, Verheijen RH, Zweemer RP, Gille JJ, et al. Histopathological characteristics of BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated intraperitoneal cancer: a clinic-based study. Familial cancer. 2003;2(2):73–78. doi: 10.1023/a:1025700807451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]