Abstract

The first synthesis of poly-amido-saccharides (PASs) from a galactose(gal)-derived β-lactam sugar monomer is reported. The polymers are prepared using a controlled anionic ring-opening polymerization and characterized by NMR, optical rotation, IR, and GPC. Galactose-derived PASs display high solubility in aqueous solutions and are noncytotoxic to HepG2, CHO, and HeLa cell lines. To evaluate whether gal-derived PASs are recognized by the gal-specific lectin present on human hepatocytes, cellular uptake of rhodamine-labeled polymers is assessed using flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy. Based on these results, the polymers are taken into cells via endocytosis that is not dependent on the gal-specific receptor on hepatocytes. Neutral, hydrophilic polymers, such as gal-derived PASs, are desirable materials for a range of biomedical applications, such as drug delivery, surface passivation, and hydrogel formation.

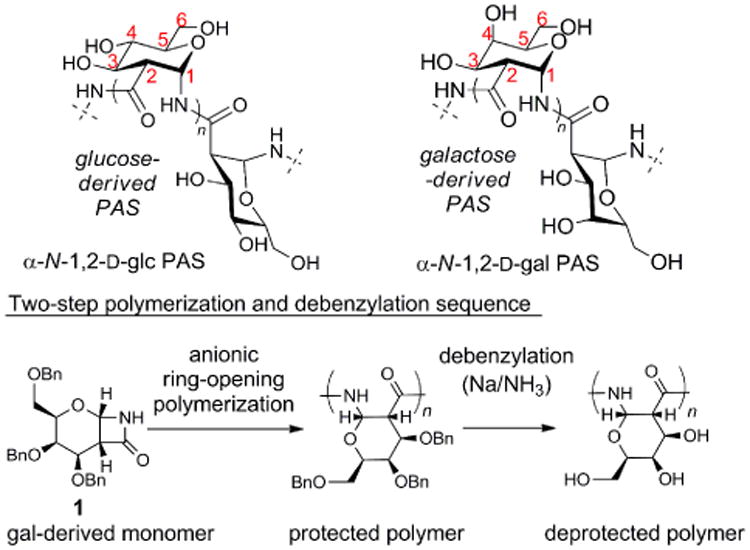

Synthetic neutral hydrophilic polymers, such as polyethylene glycols (PEG)1, polyglycerols2, poly(2-oxazoline)s (POx)3, and polyphosphoesters4 are used in a wide-range of applications. Within this family, water-soluble polymers inspired by polysaccharides5 are employed in a variety of important bio-medical contexts, for example as drug-delivery vehicles,6 as nonfouling surface coatings,7 and as hydrogel8 components. We are interested in preparing carbohydrate polymers that retain the stereochemically-defined, cyclic backbone of natural polysaccharides to understand how these structural aspects influence polymer properties. In general, such polymers are considered difficult to access synthetically.9 Recently, we reported a new approach that replaces the ether linkage found in natural polysaccharides with an amide linkage, and termed these polymers poly-amido-saccharides (PASs) (Scheme 1).10 In the initial investigation, we used a glucose-derived monomer to prepare α-N-1,2-d-glucose poly-amido-saccharides (α-N-1,2-d-glc PASs) using a two-step polymerization/deprotection sequence. Our approach is notable for allowing the controlled synthesis of enantiopure carbohydrate polymers of low dispersity (Ð). Additionally, the PASs obtained have the advantage of containing hydroxyl groups for facile covalent modification, such as conjugation to drugs/biologics or the incorporation of charged groups. Herein, we extend this methodology to the synthesis of galactose-derived PASs, specifically α-N-1,2-d-galactose poly-amido-saccharides (α-N-1,2-d-gal PASs). Compared to the glc-derived PASs, gal-derived PASs differ only in that the hydroxyl group at the C4 position is axial rather than equatorial (Scheme 1, top). This minor structural change results in polymers significantly more water-soluble than the glucose derivatives. Specifically, we report: (1) the synthesis of α-N-1,2-d-gal PASs with molecular weights as high as 35 kDa, (2) the preparation of amine-terminated PASs for subsequent functionalization, (3) cytotoxicity studies, and (4) cellular uptake studies.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of poly-amido-saccharides (PASs).

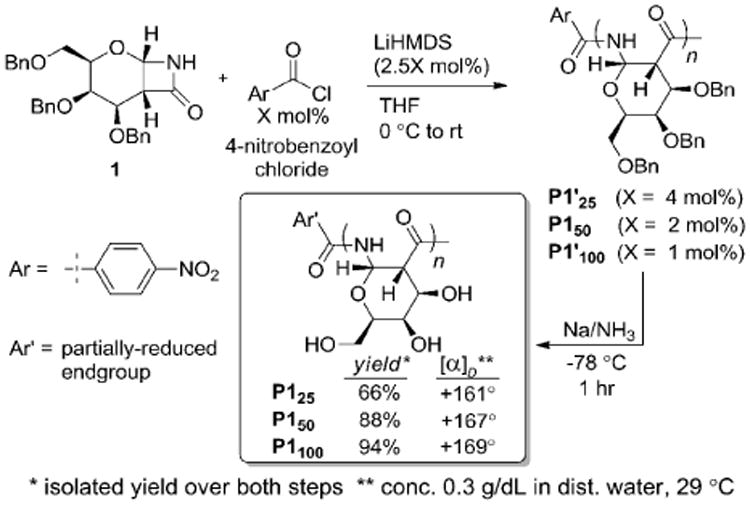

Using para-nitrobenzoyl chloride as the initiator, the anionic ring-opening polymerization11 of monomer 112 was performed at three different initiator loadings (4, 2, and 1 mol%) to prepare a series of polymers of increasing degrees of polymerization, P1'25, P1'50, and P1'100 (DPth = 25, 50, 100, respectively) (Scheme 2). Complete consumption of the monomer was observed with initiator loadings of 4 and 2 mol%. In contrast to our previous observations using the glc-derived monomer, monomer 1 was not completely consumed at an initiator loading of 1 mol%. Based on proton NMR integration of the reaction mixture, more than 90% of the monomer was consumed. The reason for polymer termination is unknown. Possible explanations include the longer polymer chains becoming unreactive due to steric bulk or the acylated β-lactam at the growing polymer chain end undergoing a side-reaction. Polymerizations of noncarbohydrate-derived β-lactam monomers have also shown a trend of incomplete conversion at low initiator loadings.11a

Scheme 2. Polymerization of 1 with acyl chloride initiator.

The resulting polymers, P1'25, P1'50, and P1'100, were characterized by 1H-NMR, with all samples having broadened peaks. A representative 13C-NMR spectrum was obtained of P1'25 (see Supporting Information). The polymers were also characterized by IR (see Figure S1 for spectra). Polymer molecular weights were determined using GPC with THF as the eluent and polystyrene standards (Table 1). The Mn-values showed the anticipated trend of increasing Mn with decreasing initiator loading. The dispersities were low, 1.1 or 1.2, as was previously found with the glucose-derived PASs.

Table 1. Polymer Characterization using GPC.

| Mn(th)/Mn(GPC)a (kDa) | Mw(GPC) a (kDa) | Ðb | DPth/DPGPC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1'25 | 11.6/15.4 | 18.2 | 1.2 | 25/34 |

| P1'50 | 23.1/28.8 | 31.5 | 1.1 | 50/63 |

| P1'100 | 46.1/81.0 | 98.4 | 1.2 | 100/176 |

| P125 | 4.8/9.0 | 10.3 | 1.1 | 25/48 |

| P150 | 9.6/15.6 | 19.0 | 1.2 | 50/82 |

| P1100 | 19.0/35.2 | 54.9 | 1.6 | 100/186 |

| P2'25 | 11.7/7.6 | 9.4 | 1.2 | 25/17 |

| P2'50 | 23.2/17.2 | 28.2 | 1.6 | 50/37 |

| P2'100 | 46.2/49.7 | 77.2 | 1.6 | 100/108 |

| P225 | 4.8/5.9 | 6.8 | 1.2 | 25/31 |

| P250 | 9.6/17.7 | 23.2 | 1.3 | 50/94 |

| P2100 | 19.0/23.2 | 47.0 | 2.3 | 100/123 |

Determined by THF GPC with polystyrene standards (P1', P2') or aqueous GPC with dextran standards (P1, P2).

Mw/Mn.

Polymers P1'25, P1'50, and P1'100 were debenzylated using sodium metal in liquid ammonia at -78 °C. Following dialysis and lyophilization, the resulting polymers (P125, P150, and P1100) were isolated as white powders. For P1100, unreacted monomer was removed during dialysis. The isolated yields over both steps, polymerization and debenzylation, ranged from (66-94%). The 1H-NMR spectra were collected in D2O and showed well resolved signals and couplings. A representative 13C-NMR spectrum of P125 showed the expected seven signals (see SI). Based on the 1H-NMR spectrum of P125, the endgroup was partially reduced, as has been previously observed with endgroups containing aromatic rings.10 Specific rotations measured in water ranged from +161° for P125 to +169° for P1100 (Scheme 2, box). The molecular weights of the deprotected polymers were characterized using aqueous GPC with dextran standards. The Mn-values were larger than expected. Computational modeling10 suggests that PASs form rod-like, rather than globular structures, and this rod-like structure may result in an over-estimation of molecular weight, as has been previously noted for other polymers.13 The dispersities of P125 (1.1) and P150 (1.2) were similar to the values observed for the protected polymers. However, the dispersity of P1100 was significantly higher. This increase in dispersity does not appear to be a result of bond cleavage, as the DPGPC-values before and after reduction were comparable (176 and 186, respectively), and therefore may be related to the difference in the solution structure of the more rod-like, linear PAS compared to the more compact, branched dextran.

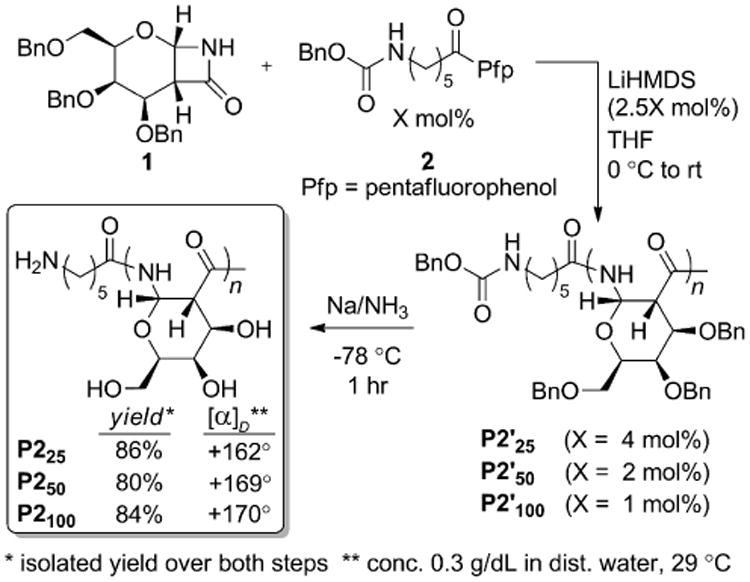

In order to perform the cellular uptake studies, we required a PAS possessing a terminal amine for subsequent functionalization with rhodamine. Thus, a Z-6-aminohexanoic acid derivative was selected because it allowed for the introduction of a benzyloxy-protected primary amine that would be deprotected under the debenzylation conditions. However, preparation and purification of the corresponding acid chloride, Z-6-aminohexanoyl chloride, was expected to be challenging because of the species' high reactivity and the fact that it contains an acid-sensitive benzyl carbamate. Knowing that acylating agents less reactive than acyl chlorides, such as anhydrides,11a can successfully initiate the controlled polymerization of β-lactams, we explored the use of the pentafluorophenol ester (Pfp) of Z-6-aminohexanoic acid.

As shown in Scheme 3, we prepared three PAS polymers (P2'25, P2'50, and P2'100) using monomer 1 and initiator 2 loadings of 4, 2, and 1 mol%, respectively. At initiator loadings of 4 and 2 mol%, complete consumption of monomer was observed. As with P1'100, the polymerization to form P2'100 did not reach full conversion. Based on proton NMR integration of the reaction mixture, more than 80% of the monomer was consumed. The 1H-NMR spectra of the P2'-polymers were similar to those of the P1-series, as expected. For P2'25 and P2'50, the benzylic protons of the benyloxy carbamate protecting group at 5.05 ppm were distinguishable from the polymer signals, confirming incorporation of the end-group. The dispersities of P2'50 and P2'100 were larger (1.6) than those observed for P1'50 and P1'100 (1.1 and 1.2, respectively). Therefore, compared to the acyl chloride initiator, initiator 2 provides similar results at a loading of 4 mol%, but shows an increase in dispersities at 2 and 1 mol%. Additionally, use of initiator 2 afforded lower monomer consumption when 1 mol% of initiator was used. The differences in polymerization results at lower initiator loadings were likely the result of the lower reactivity of Pfp esters in comparison to acyl chlorides leading to a slower rate of initiation relative to the rate of polymerization.

Scheme 3. Polymerization of 1 with Pfp ester 2.

The P2' polymer series was deprotected and isolated in the same manner as P1', and isolated yields over both steps (80-86%) were comparable to those obtained for the P1-series. The 1H-NMR spectra in D2O were similar to those of P1. For P225 and P250, signals belonging to the endgroup could be discerned (see spectra in Supporting Information). Specific rotations measured in water ranged from +162° for P225 to +170° for P2100 (Scheme 3, box). The Mn-values based on aqueous GPC were larger than expected, as observed with the P1-series. The dispersity of P2100 (2.3) was larger than that of the protected polymer, P2'100 (1.6), but the DPGPC did not decrease, as observed with P1100.

In comparison to the glc-derived polymers previously reported10, the gal-derived polymers of all molecular weights showed high water solubility. All polymers were found to be soluble at 100 mg/mL; higher concentrations were not investigated. We did not observe the formation of precipitates, as was the case with glc-derived polymers. This trend was most evident when comparing P225 to a glc-derived polymer of approximately the same molecular weight with the same endgroup. After 2 days of incubation at 37 °C, aqueous solutions of P225 remained clear whereas solutions of the glc-derived polymer became cloudy (Figure S2). Polymer solubility is a complex phenomena and therefore it is challenging to give a precise rationale for why changing the orientation of the C4 hydroxyl from equatorial to axial affects solubility dramatically. However, we speculate that the C4-hydroxyl group of the gal-derived repeat, which points into the plane above the pyranose ring, may prevent stacking between PAS chains.

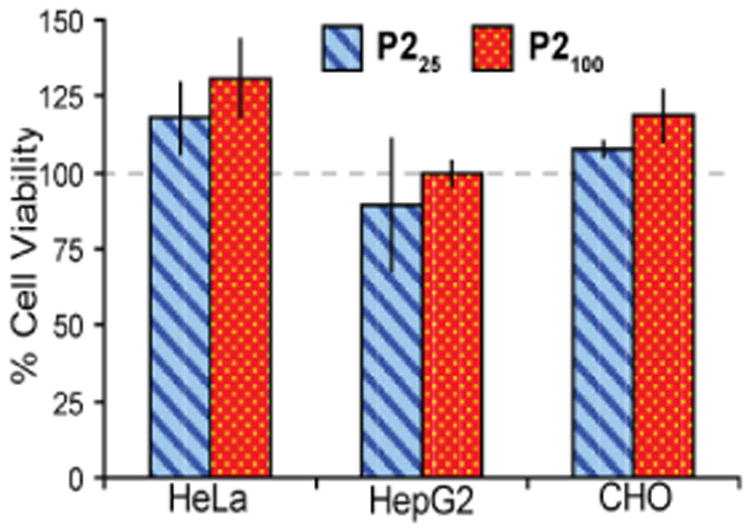

The cytotoxicity of the gal-derived PAS polymers was evaluated using an MTS cell viability assay in three cell lines: human cervix adenocarcinoma (HeLa), human liver carcinoma (HepG2), and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO). As shown in Figure 1, P225 and P2100 at a concentration of 2.0 mg/mL in media did not decrease cell viability after 48 hours of incubation in comparison to the media control, indicating no cytotoxicity.

Figure 1.

Cell viability for HeLa, HepG2, and CHO cell lines measured after incubating cells with P225 and P2100 (2.0 mg/mL in media) for 48 hours using an MTS assay. Polymers P225 and P2100 do not cause a statistically significant decrease in survivability in any of the cell lines. All experiments were done at n=3 and error bars represent standard deviation of the mean.

Neutral, hydrophilic polysaccharides, such as dextran, are known to be taken into cells via endocytosis that is not receptor mediated, and therefore fluorophore-labeled dextrans have been used to image cellular fluid flow in endosomes and lysosomes.14 However, macromolecules containing pendant galactose groups can also be taken into liver cells by an active mechanism. They are recognized and transported into the cell by the asialoglycoprotein (ASGP) receptor, a hepatic lectin that binds some galactose derivatives with free hydroxyls at the C3 and C4 positions.15 Therefore, we investigated the uptake of PASs in a human hepatocyte line expressing the ASGP receptor to determine whether this receptor would actively transport the polymers into the cell. Understanding the nature of the interaction between gal-derived PASs and gal-specific receptors is essential in defining applications for these polymers. Hydrophilic polymers, such as PEG, are often used to shield materials from specific biological interactions. If gal-derived PASs are not recognized by gal-receptors, their neutrality and high water-solubility suggest their potential as shielding polymers. Conversely, a strong interaction with gal-receptors would suggest their use in applications where this specific targeting is desired.

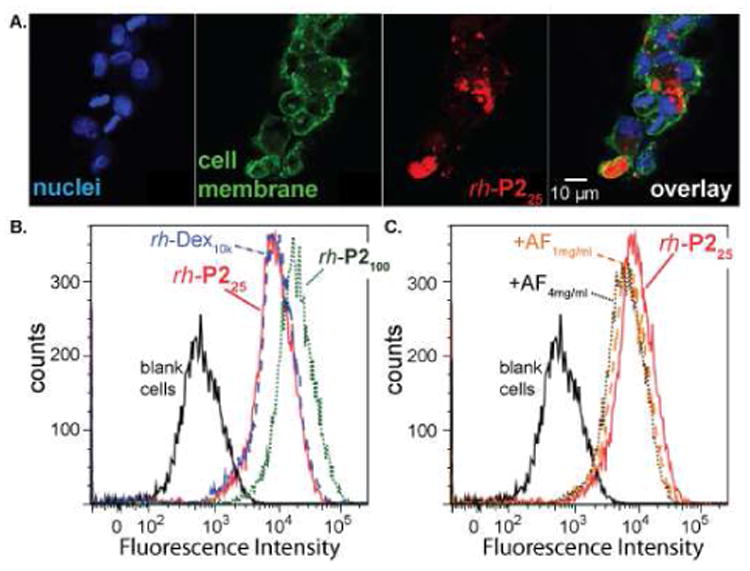

In order to monitor cell uptake, P225 and P2100 were labeled with a fluorescent rhodamine derivative via conjugation with the free amine of the endgroup, and named rh-P225 and rh-P2100, respectively. To confirm that the polymers entered hepatocytes, the cells were incubated with rh-P225 for 24 hours and then imaged with a confocal microscope (Figure 2A). The cells were fixed and stained to visualize the nucleus (Hoescht stain, blue) and membrane (concanavalin A 488 conjugate, green). The fluorescence signal of rh-P225 (red) localized within the cytosol, confirming uptake. To quantify this uptake, flow cytometry was performed with rh-P225 and rh-P2100, and for comparison, a rhodamine labeled dextran with a molecular weight of 10 kDa (rh-Dex10k). After a 24 hour incubation, rh-P225 and rh-Dex10k showed similar amounts of uptake, and rh-P2100 displayed slightly higher uptake. At 4°C, where metabolic activity was decreased, uptake of rh-P225 and rh-Dex10k was strongly inhibited, confirming that uptake was a result of endocytosis rather than passive diffusion into the cell.

Figure 2.

A. Confocal microscopy of fixed HepG2 cells after a 24 hour incubation with rh-P225 showing endocytosis. Cells were visualized with Hoechst stain (nucleus) and con A 488 conjugate (cell membrane). B. Uptake of rhodamine-labeled PAS polymers (rh-P225 and rh-P2100) was monitored using flow cytometry and compared to rhodamine-labeled dextran (rh-Dex10k) after 24 hours. C. To probe the mechanism of PAS uptake, asialofetuin (AF), a competitive binder of the ASPG receptor, was added at 1 mg/mL and 4 mg/mL. Significant inhibition of rh-P225 uptake was not observed, confirming that uptake is not strongly dependent on the gal-specific ASPG receptor. The concentration of rhodamine-labeled PAS was 25 µg/mL for all experiments.

To further probe the mechanism of uptake, we investigated rh-P225 uptake in the presence of asialofetuin (AF), a competitive binder for the ASGP receptor.16 If rh-P225 was actively endocytosed by the ASGP receptor, we would expect AF to inhibit uptake through competition. As shown in Figure 2C, addition of 1 and 4 mg/mL of AF did not significantly decrease rh-P225 uptake. This result suggested that uptake was not strongly dependent on the gal-specific receptor. The fact that rh-P225 and rh-P2100 displayed similar amounts of uptake relative to rh-Dex10k, a polymer that does not contain galactose and, thus, was not actively taken up, also agreed with the conclusion that the gal-derived PAS polymers were not being recognized by the ASPG-receptor. Finally, under the same conditions with the same rhodamine label, glucose-derived PASs of similar molecular weights showed comparable uptake into hepatocytes, further strengthening the argument that uptake was not mediated by the ASPG-receptor (data not shown).

In summary, the synthesis and characterization of gal-derived PASs are reported. Polymerization using either an acyl chloride or pentafluorophenol ester initiator results in complete consumption of monomer when 4 or 2 mol% initiator is employed. When 1 mol% initiator is used, some (< 20%) unreacted monomer remains with both initiators. However, unreacted monomer is removed by dialysis to obtain pure polymers in good to high yields. The resulting polymers are characterized using NMR, optical rotation, IR, and GPC. The polymers of all molecular weights are highly water soluble, in contrast to the previously reported glc-derived polymers,10 and are nontoxic to HeLa, HepG2, and CHO cell lines. Based on microscopy and flow cytometry studies, the polymers are taken into cells via endocytosis that is not dependent on the gal-specific receptor on hepatocytes. These results suggest that α-N-1,2-d-gal PASs are of interest for applications requiring hydrophilic polymers that do not strongly interact with biological receptors. Future work will focus on identifying biomedical applications where the unique architecture and properties of these water-soluble, neutral, structurally-defined carbohydrate polymers can offer advantages over existing systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

E.L.D acknowledges receipt of an NIH/NIGMS Postdoctoral Fellowship (1F32GM097781). The authors thank Aaron Colby for obtaining confocal images.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: Experimental details, supplemental figures, 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Knop K, Hoogenboom R, Fischer D, Schubert US. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:6288. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dong Y, Gunning P, Cao H, Mathew A, Newland B, Saeed AO, Magnusson JP, Alexander C, Tai H, Pandit A, Wang W. Polym Chem. 2010;1:827. [Google Scholar]; (c) Oelker AM, Berlin JA, Wathier M, Grinstaff MW. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:1658. doi: 10.1021/bm200039s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Wilms D, Stiriba SE, Frey H. Acc Chem Res. 2009;43:129. doi: 10.1021/ar900158p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Khandare J, Calderon M, Dagia NM, Haag R. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2824. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15242d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ray WC, Grinstaff MW. Macromolecules. 2003;36:3557. [Google Scholar]; (d) Kainthan RK, Muliawan EB, Hatzikiriakos SG, Brooks DE. Macromolecules. 2006;39:7708. [Google Scholar]; (e) Shenoi RA, Lai BFL, Kizhakkedathu JN. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:3018. doi: 10.1021/bm300959h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luxenhofer R, Han Y, Schulz A, Tong J, He Z, Kabanov AV, Jordan R. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2012;33:1613. doi: 10.1002/marc.201200354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang S, Li A, Zou J, Lin LY, Wooley KL. ACS Macro Lett. 2012;1:328. doi: 10.1021/mz200226m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Meier S, Reisinger H, Haag R, Mecking S, Mulhaupt R, Stelzer F. Chem Comm. 2001:855. [Google Scholar]; (b) Baskaran S, Grande D, Sun XL, Yayon A, Chaikof EL. Bioconjugate Chem. 2002;13:1309. doi: 10.1021/bc0255485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lienkamp K, Kins CF, Alfred SF, Madkour AE, Tew GN. J Poly Sci A: Polymer Chemistry. 2009;47:1266. [Google Scholar]; (d) Wathier M, Stoddart SS, Sheehy MJ, Grinstaff MW. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15887. doi: 10.1021/ja106488h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kramer JR, Deming TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15068. doi: 10.1021/ja107425f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Fox ME, Szoka FC, Fréchet JMJ. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:1141. doi: 10.1021/ar900035f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee CC, Liu Y, Reineke TM. ACS Macro Lett. 2012;1:1388. doi: 10.1021/mz300505t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Li H, Cortez MA, Phillips HR, Wu Y, Reineke TM. ACS Macro Lett. 2013;2:230. doi: 10.1021/mz300660t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Metzke M, Bai JZ, Guan Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:7760. doi: 10.1021/ja0349507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Metzke M, Guan Z. Biomacromolecules. 2007;9:208. doi: 10.1021/bm701013y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burdick JA, Prestwich GD. Adv Mater. 2011:23, H41. doi: 10.1002/adma.201003963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gruner SAW, Locardi E, Lohof E, Kessler H. Chem Rev. 2002;102:491. doi: 10.1021/cr0004409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dane EL, Grinstaff MW. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:16255. doi: 10.1021/ja305900r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Zhang J, Kissounko DA, Lee SE, Gellman SH, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1589. doi: 10.1021/ja8069192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang J, Gellman SH, Stahl SS. Macromolecules. 2010;43:5618. [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhang J, Markiewicz MJ, Weisblum B, Stahl SS, Gellman SH. ACS Macro Lett. 2012:714. doi: 10.1021/mz300172y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kałuża Z, Abramski W, Bełżecki C, Grodner J, Mostowicz D, Urbański R, Chmielewski M. Synlett. 1994:539. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakamoto J, Rehahn M, Wegner G, Schlüter AD. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2009;30:653. doi: 10.1002/marc.200900063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lencer WI, Weyer P, Verkman AS, Ausiello DA, Brown D. Am J Physiol Cell Physio. 1990;258:C309. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.2.C309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stockert RJ. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:591. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zanta MA, Boussif O, Adib A, Behr JP. Bioconjugate Chem. 1997;8:839. doi: 10.1021/bc970098f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.