Abstract

Fluorescent dyes are widely used in the detection of labile (free or exchangeable) Zn2+ and Ca2+ in living cells. However, their specificity over other cations and selectivity for detection of labile vs. protein-bound metal in cells remains unclear. We characterized these important properties for commonly used Zn2+ and Ca2+ dyes in a cellular environment. By tracing the fluorescence emission signal along with UV-Vis and size exclusion chromatography-inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (SEC-ICP-MS) in tandem, we demonstrated that among the dyes used for Zn2+, Zinpyr-1 fluoresces in the low molecular mass (LMM) region containing labile Zn2+, but also fluoresces in different molecular mass regions where zinc ion is detected. However, FluoZin™-3 AM, Newport Green™ DCF and Zinquin ethyl ester display weak fluorescence, lack of metal specificity and respond strongly in the high molecular mass (HMM) region. Four Ca2+ dyes were studied in an unperturbed cellular environment, and two of these were tested for binding behavior under an intracellular Ca2+ release stimulus. A majority of Ca2+ was in the labile form as tested by SEC-ICP-MS, but the fluorescence from Calcium Green-1™ AM, Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1, Fura red™ AM and Fluo-4 NW dyes in cells did not correspond to free Ca2+ detection. Instead, the dyes showed non-specific fluorescence in the mid- and high-molecular mass regions containing Zn, Fe and Cu. Proteomic analysis of one of the commonly seen fluorescing regions showed the possibility for some dyes to recognize Zn and Cu bound to metallothionein-2. These studies indicate that Zn2+ and Ca2+ binding dyes manifest fluorescence responses that are not unique to recognition of labile metals and bind other metals, leading to suboptimal specificity and selectivity.

Keywords: Zinc, Calcium, fluorescent dyes, specificity, selectivity, fluorescent probes, metal imaging dyes, metal detectors, indicators

Introduction

Metal homeostasis is tightly regulated in living cells. Numerous biological stimuli such as hormones, pathogens and tumorigenesis trigger responses that alter the total and labile metal fraction in cells and their distribution within intracellular organelles1–5. Modulation of metals controls important cellular processes including transcription, enzyme function, signaling, and metabolism1,6–10. Thus, analysis of metal flux provides mechanistic insights into cell function.

Atomic absorption spectroscopy (AA), inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometry (ICPAES) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICPMS) have been invaluable in accurate metal detection and quantification in biological samples11. But, they do not allow visualization of metal flux and distribution within cells. The development of small molecule, cell permeable fluorescent dyes has facilitated detection of metal flux and distribution in real time on living cells through confocal microscopy12. These dyes fluoresce once they are coordinated with the metal ions alone or in a shared coordination sphere. Modification with acetoxy-methyl (AM) esters for cell permeability has enhanced the applicability of these dyes13. The combined use of red and green fluorescent dyes enables simultaneous imaging of two metals in cells14. These advantages and others such as ratiometric measurement15 and quantification of fluorescent signals16 have led to an increasingly popular use of metal binding dyes in microscopy and flow cytometry. Since their initial development, many dyes have been generated with intended specificity to metals such as Ca, Zn and Fe.

Zn is the second most abundant transition metal in living cells that is essential for cellular processes such as transcription, translation, enzyme function, protein folding and signaling17–19. Cells possess a labile Zn2+ pool in the picomolar to low nanomolar concentrations that may be stored in organelles such as the Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and zincosomes20–22. Imaging Zn2+ using Zinpyr-1™, FluoZin™-3 AM or Newport Green™ DCF dyes has contributed to the current understanding of intracellular flux and distribution of Zn in cells such as those of the immune system, pancreatic islets and neurons23–26. Intracellular Ca2+ imaging has been extensively employed in studying mobilization, release and uptake by mitochondria and ER in cells such as cardiomyocytes and neurons27,28. The Ca2+ cytosolic concentration is reported in the high nanomolar to low micromolar range. Widely used probes for Ca2+ include Calcium Green-1™ AM, Fura-2 AM, Fura red™ AM, Fluo-3 AM, Fluo-4 and Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1 AM27,29–32.

Specificity and sensitivity of fluorescent dyes are influenced by intracellular factors including pH, concentration of competing metals, ionic strength, preference for hydrophobic regions and binding constants12,33–35. Commercially available dyes have been characterized for these parameters, largely in buffered solutions, but their behavior within the complex intracellular environment remains unclear36,37. While suitable for partial characterization, these buffered solutions lack cellular constituents such as membranes, organelles and transporters (proteins) that are required to bind, store or transport metals. Binding properties of dyes in buffered solutions may be quite different from their behavior in an intracellular environment. For example, cellular pH varies spatially and temporally from an acidic pH of 5.4 to a physiological pH of 7.438,39. The changes in pH may cause differential behavior by dyes in different compartments, where binding site availability is typically a function of pH. The fluorescence signal is influenced by the strength of these interactions, and quantification of labile or exchangeable metal pools within cells may be challenging. Given the extensive use of metal binding dyes in cellular imaging and flow cytometry to obtain data about relative metal concentration, exchangeable pools and trafficking, additional studies are necessary to dissect their specificity to particular metals and selectivity for metal binding species within the complex cellular environment.

In this study, we have defined specificity to mean binding to a particular metal ion, while selectivity refers to one or more molecular weight regions in which binding to a specific metal ion takes place. We characterized the specificity and selectivity of four Zn2+ binding and four Ca2+ binding dyes in an intracellular environment using a bone marrow macrophage cell line. The Zn2+ dyes selected were Zinpyr-1, FluoZin™-3 AM, Newport Green™ DCF and Zinquin ethyl ester, and those chosen for Ca2+ were Calcium Green-1™ AM, Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1, Fura red™ AM and Fluo-4 NW.

Experimental

Reagents

Rosewell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI-1640) media was obtained from Hyclone Laboratories, (Utah); sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and analytical grade ammonium acetate were from Fisher Scientific (NJ) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) anhydrous was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis). Phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin were obtained from Calbiochem (USA). All aqueous solutions were prepared in 18 Ω Milli Q water. The fluorescent dyes, FluoZin™-3 AM, Newport Green™ DCF, Fura red™ AM, Calcium Green-1™ AM, and Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1 were purchased from Molecular Probes (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY); Zinpyr-1 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and Zinquin ethyl ester from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY), Fluo-4 NW (No-Wash) Ca2+ assay kit was kindly provided by Dr. William Miller (University of Cincinnati Medical Center).

Cell line

Bone marrow macrophage cell line (BMC) was obtained from Dr. Kenneth Rock40 and cultured in tissue culture flasks with media (RPMI + 10% fetal bovine serum + gentamycin) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Confluent cultures were passaged every 3–4 days. 1.25 × 106 cells were plated in 2 ml media in 35 × 10 mm tissue culture dishes for 24 h prior to treatment of BMCs with metal binding dyes.

Treatment with fluorescent dyes

The Zn2+ and Ca2+ binding dyes were dissolved in anhydrous DMSO and stored in the dark at −20°C. BMCs were washed twice with Ca2+ and magnesium free phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 2 mM EDTA to chelate extracellular metals. Cells were then treated with the indicated concentration of dyes (Table 1) or with DMSO control in RPMI media without serum or in assay buffer (for Fluo-4 NW, as per manufacturer’s instructions) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 5% CO2 in the dark. For analysis of Ca2+ binding by the dyes under a Ca2+ release stimulus, BMCs were treated with 50 ng/ml PMA, and 500 ng/ml ionomycin for 10 min to trigger intracellular Ca2+ release prior to addition of the dye. Post-incubation, BMCs were washed twice with Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) to remove unbound and extracellular dye and lysed with 0.1% SDS in Milli Q deionized water on ice for 20 min in the dark. Cell lysates were filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane and 50 μl of cell lysate was immediately injected into the HPLC-ICP-MS system for analysis.

Table 1.

FLD conditions for each probe studied, the excitation and emission were taken from the vendor instructions, while the spectra acquired were set 20 nm apart from the excitation wavelength to 750 nm.

| Name of the probe | Concentration used (μM) | Metal Ion (2+) | Excitation/Emission for single wave length FL λ, nm | Range for emission spectra acquired λ, nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zinpyr-1 | 5 | Zn | 490/530 | 510–750 |

| FluoZin™-3 AM | 5 | Zn | 494/516 | 514–750 |

| Newport Green™ DCF | 5 | Zn | 505/535 | 525–750 |

| Zinquin ethyl ester | 25 | Zn | 368/490 | 388–750 |

| Calcium Green-1™ AM | 5 | Ca | 506/530 | 526–750 |

| Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1 | 5 | Ca | 466/494 | 486–750 |

| Fura red™ AM | 5 | Ca | 488/660 | 508–750 |

| Fluo-4 NW | 10 | Ca | 494/516 | 520–750 |

Size exclusion chromatography

The separations were carried out with an Agilent 1100 HPLC (Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a solvent degasser, binary pump, thermostated auto sampler, thermostated column compartment, diode array UV-Vis detector equipped with a semi-micro flow cell and a diode array fluorimetric detector equipped with a standard flow cell. The system was controlled using Chemstation software.

The size exclusion column used was a TSK gel 3000SW 7.5 × 300 mm (Tosoh Bioscience, Germany) (exclusion range ≥600kDa-10 kDa), the mobile phase was 50 mM ammonium acetate pH 7.4 at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min−1. The size exclusion column was calibrated using a UV detector (wavelength, 280 nm) using a gel filtration standard mixture Bio-Rad Laboratories (Life Science Research, CA, USA, thyroglobulin, 670kDa; γ-globulin, 158 kDa; ovalbumin, 44 kDa; myoglobin, 17 kDa; and vitamin B12, 1.3 kDa) r = 0.997. Toward the end of the study the column had to be replaced. As is common with SEC columns, the new one showed shorter retention times for LMW or labile fractions of cations, as fewer nonspecific interactions occur in a new stationary column bed. However, since this study primarily compares the FL detection with the ICP-MS detection, the comparisons are unaffected. The older column was used in Figs. 3 and 4.

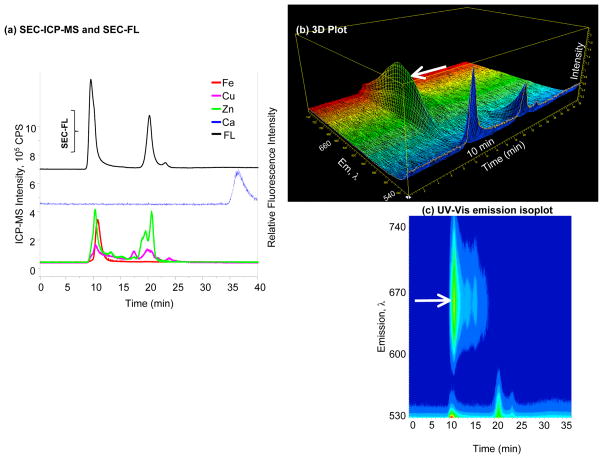

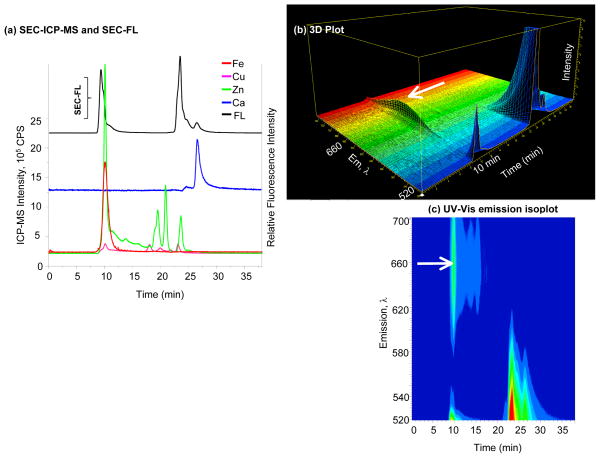

Figure 3. Specificity and selectivity of Calcium Green-1™ AM.

(a) SEC-FL and SEC-ICP-MS chromatograms of Calcium Green-1™ AM; Fe, Cu, Zn and Ca signals represented by solid lines belong to the left Y axis, while the SEC-FL signal represented by the black line corresponds to the right Y axis; the majority of the FL response is at 10 min (HMM), and subsequent SEC-FL signals are apparent, but Ca2+ is not associated with any of these; (b) 3D representation of emission wavelength, time and intensity; (c) UV-Vis emission isoplot of Calcium Green-1™ AM; signals at 10 min and 20 min are observed, the arrow indicates the second SEC-FL band at 660 nm in the HMM region.

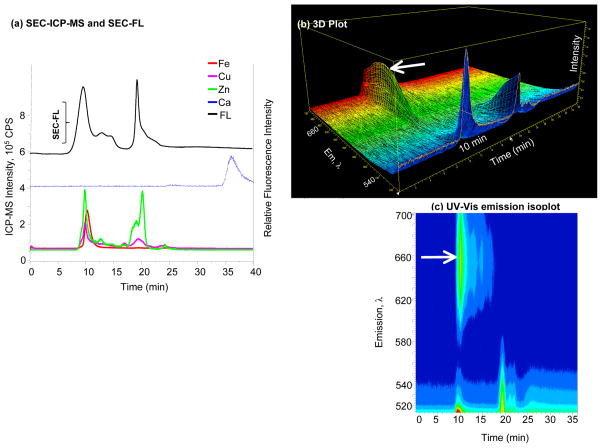

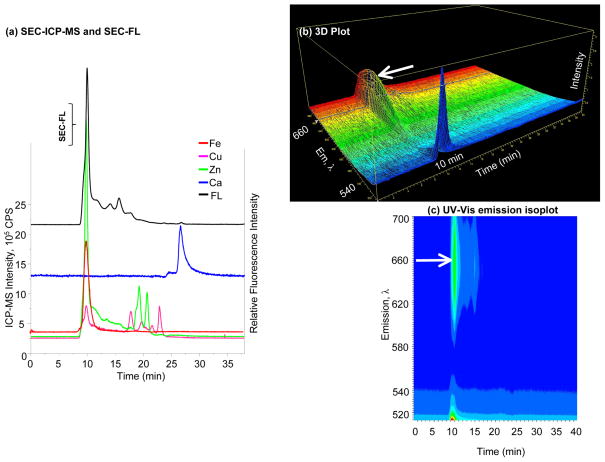

Figure 4. Specificity and selectivity of Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1.

(a) SEC-FL and SEC-ICP-MS chromatograms of Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1; Fe, Cu, Zn and Ca signals represented by solid lines belong to the left Y axis, while the SEC-FL signal represented by the black line corresponds to the right Y axis; SEC-FL signals are observed at HMM and ~20 min, but Ca2+ is not associated with any of these; (b) 3D representation of emission wavelength, time and intensity; (c) UV-Vis emission isoplot of Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1; the SEC-FL signal shows a spectral behavior with two emission bands in the HMM region, the second band is indicated by the arrow.

UV-Vis, FL and ICP-MS detection

Three detectors were used in tandem; first the UV-Vis detector generated spectra from 210 to 600 nm in 2 nm steps, at a speed of 2 spectra per second. As second detector a diode array fluorescence detector (Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used and conditions were adjusted according to the optimum excitation/emission wavelengths recommended for each specific dye. Emission spectra were collected at a speed of one spectrum every five seconds. The details are shown in Table 1.

The effluent from the HPLC was directly connected to the ICPMS nebulizer by a 0.17 mm ID PEEK capillary. The specific detection of elements in the size exclusion chromatography (SEC) separated cell lysates was carried out in an Agilent 8800x ICP-MS (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), equipped with a micro mist nebulizer, a cooled double pass spray chamber and standard torch. The operating conditions were as follows: forward power, 1550 W; plasma gas flow rate 15 L min−1, carrier gas flow, 0.91 L min−1; makeup gas 0.12 L min−1; collision gas, He at 4.0 mL min−1; quadrupole bias, −16.0 V; octopole bias −18.0 V for a +2 V energy discrimination setting. The isotopes monitored were 23Na, 27Al, 34S, 39Mg, 44Ca, 51V, 55Mn, 56Fe, 59Co, 60Ni, 63Cu, 66Zn and 114Cd.

Proteomics analysis

Protein identification experiments were carried out on the control samples, as a shot-gun bottoms-up approach. In brief, the different fractions of the SEC chromatogram were collected off-line for seven consecutive injections of 100 microliters each and the fractions were concentrated by freeze-drying (a fraction could be one or more than one SEC peak). The pellets obtained after freeze drying were re-suspended in 25 μL of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, then 2 μL of 100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) were added as reducing buffer and the mixture was heated at 95 °C for 5 minutes. After cooling the sample, an alkylation step was carried out to protect the thiol groups of the cysteine residues by adding 3 μL of 100 mM iodoacetamide. The mixture was then kept in the dark at room temperature for 20 minutes. After alkylation, 2 μL of modified sequence grade trypsin solution were added and incubated at 37 °C for 2 hours and then 2 μL of additional trypsin was added to complete the reaction, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 12 hours. 1.0 μL of formic acid was added to stop the reaction, and the solution was ultra-filtered through a 10 kDa filter to remove the undigested proteins and the unreacted trypsin. Filtrate was analyzed by nanoLC-ESI-ITMS.

An Agilent 6300 Series HPLC-CHIP-ESI-Ion Trap XCTsystem (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) coupled to an Agilent model 1200 LC, equipped with both capillary and nano pump, was used for peptide identification. Three microliters of sample was loaded via the capillary pump onto the on-chip enrichment column. The chip used consists of a Zorbax 300SB C18 enrichment column (4 mm × 75 μm, 5 μm) and a Zorbax 300SB C18 analytical column (150 mm × 75 μm, 5 μm, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Samples were loaded onto the enrichment column at a flow rate of 3 μL min−1 with a 97:3 ratio of solvent A (0.1% FA (v/v) in water) and B (90% ACN (acetonitrile), 0.1% FA (v/v) in water). After the enrichment column was loaded, the on-chip microfluidics switched to the analytical column at a flow rate of 0.3 μL min−1. The following gradient conditions were used in the analysis: 0–5 min, 10% B; 5–80 min, 40%B; 80–100 min, 70% B; 100–110 min, 0% B. Full scan mass spectra were acquired over the m/z range 150–2200 in the positive ion mode. For MS/MS experiments, experimental conditions consisted of: m/z range: 150–2200; isolation width: 2 m/z units, fragmentation energy: 30–200%, fragmentation time: 100 ms.

Results

BMCs were used to trace the fluorescent behavior of dyes as a function of exchangeable metal or metal moiety. The dye fluorescence was evaluated primarily in two ways; the low molecular mass (LMM) response, and the target metal specificity by comparing size exclusion chromatography-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (SEC-ICP-MS) detection with SEC-fluorescence detection (SEC-FL). Cells, rather than aqueous solutions, were chosen to provide an evaluation of metal-dye interactions and fluorescence responses in a cellular environment since buffered aqueous solutions and cell matrices are markedly different.

The use of UV-Vis, fluorescence and ICP-MS as online tandem detectors provides information about the binding of dyes to specific molecular masses eluted from SEC column. The UV-Vis absorbance spectra along with the SEC retention time can be used to distinguish proteins, nucleic acids, peptides and LMM compounds; while the ICP-MS provides a very specific and sensitive signal for the metal elution profiles from the high molecular mass (HMM, ≥600 kDa) ranging to the LMM regions. The simultaneous appearance of ICP-MS and dye fluorescence responses in the LMM region is indicative of specific dye binding to a particular labile metal. However, in the findings shown below, dye fluorescence was not always detected in the same molecular mass region where the metal was unambiguously identified by ICP-MS. This is an important observation, particularly in the LMM region where labile metals are expected to appear in the SEC chromatogram.

For dyes that recognize the labile fraction of a particular metal, the SEC-FL retention time should correspond to the LMM region of the SEC (lower than 5 kDa, at or after 22 min) and it is expected that fluorescence will be seen only in the LMM chromatographic regions and only if there is metal association with the dye. Any fluorescence signal before 22 min corresponds to an association between the dye and the metal at HMM, in some cases, possibly proteins. Any SEC-FL signal differing from the SEC-ICP-MS signal of the metal in question at a certain molecular mass range shows a lack of specificity for a particular metal or selectivity to one or more species of the same metal and may also represent background fluorescence of the dye.

All the experiments were carried out in biological triplicates on different days and produced similar results. The selection of BMCs was based on our previous experience with SEC-ICP-MS using this cell line for metallomics studies in the lab. The unstained cell lysates of BMCs served as a negative control and showed no FL signal at any molecular fraction (Supplementary Figure 1). The ICP-MS and UV-Vis emission profiles show the distribution of Fe, Cu, Zn, Ca and Ni across high, medium and low molecular mass regions.

Zn2+ binding dyes

We selected the dyes that have been popularly used in imaging this metal to determine the relative response to Zn bound to larger biomolecules versus labile Zn2+. BMCs were treated with Zn2+ dyes, followed by analysis of the SEC-FL response of the dye in correlation with the SEC-ICP-MS signals for detection of Zn, Cu, Fe, Ni and S.

Detection of labile Zn2+

The goal of numerous Zn imaging studies has been to target the labile Zn2+ fraction to observe its behavior under varied stimuli. Though the total cellular zinc concentration is in the micromolar range, only picomolar quantities exist in labile form, making studies on this fraction challenging. Therefore, we evaluated the propensity of Zn dyes to recognize the labile Zn2+ fraction in an intracellular environment.

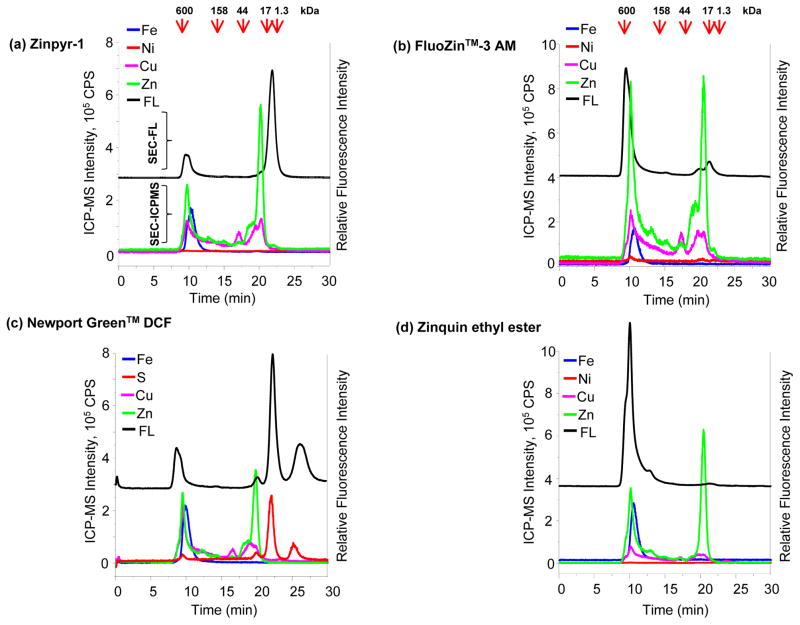

Among the four dyes analyzed, Zinpyr-1 produced the highest fluorescence response corresponding to the labile Zn2+ fraction. Treatment of BMCs with Zinpyr-1 resulted in a strong SEC-FL signal at 22 min (Figure 1a) that correlated with detection of a small, labile or LMM Zn2+ fraction evident in the SEC-ICP-MS chromatogram (Figure 2a). An SEC-ICP-MS response for other metals was not detected in this region, indicating a specificity of the SEC-FL response of Zinpyr-1 for the detection of labile Zn2+. This signal represents the only anticipated response of the dye in terms of its usual applicability to determine labile Zn2+. Since the response of Zinpyr-1 was relatively low in the HMM region, the dye exhibited highest selectivity to the LMM fraction or to labile Zn2+.

Figure 1. Specificity and selectivity of Zn2+ binding dyes.

SEC-FL and SEC-ICP-MS chromatograms of (a) Zinpyr-1; (b) FluoZin™-3 AM; (c) Newport Green™ DCF; (d) Zinquin ethyl ester; Fe, Ni, Cu, Zn and S signals are represented by solid lines and belong to the left Y axis; the SEC- FL signal is represented by the black line and corresponds to the right Y axis, fluorescence signal is offset to allow easy comparison; the MW markers are shown at the top of the chromatograms.

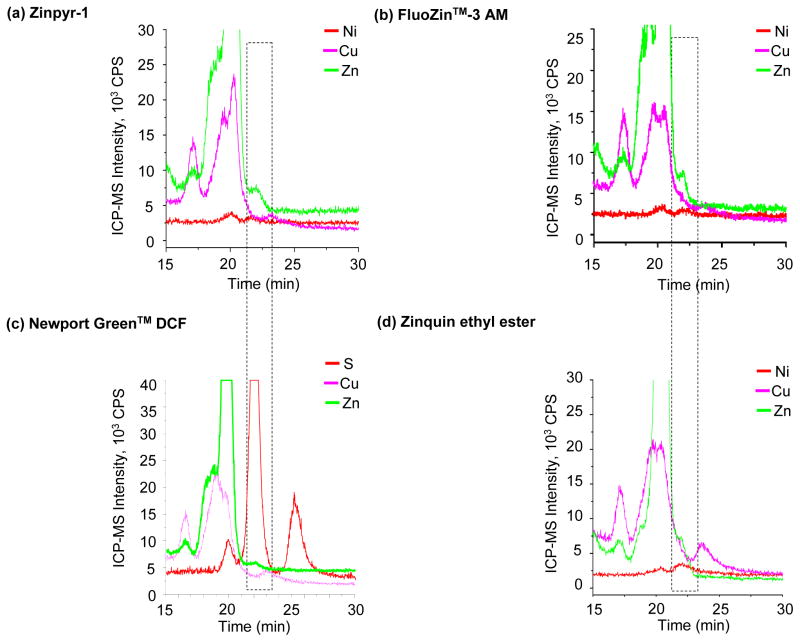

Figure 2. Zoom in of the LMM region of SEC-ICP-MS trace show in Figure 1.

Zoom in of the 15–30 min fraction of the SEC-ICPMS traces shown in Figure 1 for (a) Zinpyr-1; (b) FluoZin™-3 AM; (c) Newport Green™ DCF; (d) Zinquin ethyl ester; three of the four dyes, except Newport Green™ DCF, show a Zn2+ signal in the LMM region; the intensity of Zn2+ signal of LMM species is far less than that observed in the HMM regions.

FluoZin™-3 AM is a widely used dye in imaging labile Zn2+ in cells23,41–43. We therefore sought to determine the selectivity and specificity of this dye for the metal. The SEC-FL response produced by FluoZin™-3 AM at the ~22 min region representing labile Zn2+ was 11 fold weaker than the response generated upon interaction of the dye with HMM species in the SEC-ICP-MS chromatogram (Figure 1b and 2b). In effect, the labile metal detection response of FluoZin™-3 AM was ~10% of the overall SEC-FL signal generated by the dye as measured by area under the curve of the fluorescence response. Thus, in bioimaging applications, interpretation of the total fluorescence signal produced by this dye as a representation of the labile Zn fraction may lead to an over estimation of exchangeable Zn2+ in the sample.

Newport Green™ DCF has been used physiologically to visualize free Zn2+ in dendritic cells25. In buffered solutions, the dye fluorescence is enhanced in the presence of zinc, but it also binds chromium, nickel, titanium and zirconium44 and has a high affinity for Cu and Fe45. The fluorescence behavior of this dye showed a different trend when compared to Zinpyr-1 and FluoZin™-3 AM. Interestingly, Newport Green™ DCF generated two fluorescence responses at the LMM region past 21 min. Although, a very small labile Zn2+ fraction was detected by SEC-ICP-MS at 22 min in the chromatogram, the fluorescence response of this dye correlated with the detection of S throughout the chromatogram. Of note, the dye fluoresced in the LMM region at 26 min, which did not only lack Zn2+, but was a region where none of the metals analyzed were detected. However, ICP-MS analysis identified two S peaks at the LMM region that aligned exactly with the SEC-FL response of Newport Green™ DCF (Figures 1c and 2c). This S binding behavior was unique to Newport Green™ DCF, and was not observed with other Zn2+ dyes (data not shown). Since the active chelating portion of the dye is cation-specific, the SEC-FL signals may result from dye binding to S containing species associated to a cation, which was not included in the suite of metals studied. The SEC-ICP-MS analysis of Newport Green™ DCF coupled with its fluorescence response suggests that detection of physiologically low concentrations of labile Zn may not be a characteristic of the dye in an intracellular environment.

Next, we studied the ability of zinquin ethyl ester, an analog of 6-Methoxy-(8-p-toluenesulfonamido) quinoline (TSQ), to recognize and bind labile Zn2+. Compared to Zinpyr-1 that produced strong fluorescence and Newport Green™ DCF, which led to a relatively weaker fluorescence response, Zinquin ethyl ester generated a very weak SEC-FL signal in the 22 min fraction (Figure 1d) comprising LMM Zn2+ (Figure 2d). Further, there was a minor overlap of the SEC-FL signal at 22 min with the Zn and Cu SEC-ICP-MS peaks, although the fluorescence intensity of Zinquin ethyl ester at this region was very low. Thus, the fluorescence signal contributed by this dye in the LMM region was less than 2% of the chromatographic peak area.

In the context of specificity of Zn2+ binding dyes in the LMM region, Zinpyr-1 and FluoZin™-3 AM generated specific responses to the LMM Zn2+ fraction; the fluorescence signal generated by Zinpyr-1 was stronger than that of FluoZin™-3 AM in this region. On the other hand, the association of Zinquin ethyl ester with the LMM region was minimal and generated an very weak response in the labile Zn2+ fraction. Newport Green™ DCF demonstrated a lack of specificity to Zn2+ in the intracellular environment of BMCs, based on the association of the SEC-FL signal with the detection of S in the chromatogram.

Binding behavior of Zn2+ dyes in high and mid molecular mass regions

In general, Zn2+ dyes poorly fluoresced in the LMM region, with the exception of Zinpyr-1. Despite a weak signal, cellular microscopic imaging analysis of Zn using these dyes leads to a bright and detectable fluorescence signal23,25,46,47. This prompted us to speculate that a majority of the fluorescence response may be generated upon association of the dye with higher molecular masses that elute prior to 22 min in the SEC-ICP-MS chromatogram.

Upon observing the fluorescence behavior of the Zn2+ dyes throughout the chromatogram, association of the dyes with higher molecular masses was evident. All the four dyes analyzed manifested a strong SEC-FL response in the HMM region (≥600kD for the SEC) eluting at 9 min (Figures 1a–1d). However, there was an apparent difference in the fluorescence intensity generated by individual dyes in this region. In this regard, although Zinpyr-1 produced an SEC-FL signal at 9 min, it was relatively weaker than Newport Green™ DCF. FluoZin™-3 AM and Zinquin ethyl ester generated a strong fluorescence upon association to biomolecules in this region, indicating a greater affinity of these dyes for metals in the HMM fraction. The comparative intensity in fluorescence signals generated by the dyes in this region was Zinpyr-1 < Newport Green™ DCF < FluoZin™-3 AM < Zinquin ethyl ester from lowest to the highest response, indicating that Zinquin ethyl ester exhibited the strongest SEC-FL response in the HMM region. This fraction constitutes biomolecules such as large or multi-protein complexes, nucleic acids, polysaccharides, membrane structures and incompletely lysed organelles that may be minimally retained based on the short elution time (void volume for this column indicating no retention). With regard to specificity of the Zn2+ dyes in the HMM fraction, all the metals analyzed including Zn, Fe, Cu and Ni were detected between 9–11 min of the SEC-ICP-MS chromatogram. Although the SEC-FL response of the dyes appeared to correlate with the peak for Zn at 9 min, there was a fluorescence overlap with the peaks for Fe, Cu and Ni (Figures 1a–1d). Thus, the net fluorescence signal generated by the dyes in the HMM region may result from the association of the dye with more than one metal.

The Zn2+ binding dyes also exhibited differential fluorescence behavior in the mid molecular mass region (500 kDa–10 kDa). SEC-ICP-MS analysis showed peaks for Cu as well as Zn between 11 and 20 min of the SEC chromatogram (Figure 1a). Based on proteomic analysis, the Zn and Cu binding peak at 20 min contained the metal binding protein, metallothionein (Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S2). Zinpyr-1 exhibited low fluorescence in the high and mid molecular mass regions (Figure 1a). The weak SEC-FL signals produced by FluoZin™-3 AM resulted from an association of the dye with a fraction of ~158 kDa at ~15 min and of ~20 kDa at 20 min, both of which correlated with the retention time of Zn and Cu (Figure 1b). Newport Green™ DCF fluoresced in the mid molecular mass region at 20 min correlating with the Zn, Cu and S peaks observed by SEC-ICP-MS (Figure 1c). The responsiveness of the dye to S peaks throughout the chromatogram suggested that fluorescence was unlikely a result of specific Zn2+ binding. For Zinquin ethyl ester, multiple fluorescence signals were observed between the HMM and mid molecular mass fractions ranging from ~600 kDa to 100 kDa (Figure 1d). The elution profile of the fluorescence signals corresponded to retention time for Zn detected by SEC-ICP-MS, suggesting interaction of this dye with Zn-associated cell organelles, membrane structures or complex proteins in the HMM region.

Ca2+ binding dyes

Several dyes have been developed to analyze the flux of Ca2+ in single cells as well as in high throughput assays14,27,30,48,49. We found that under the ‘resting state’ a majority or all of the intracellular Ca2+ appeared in the LMM fraction of the SEC-ICP-MS chromatogram as labile Ca2+ (Supplementary Figure S1).

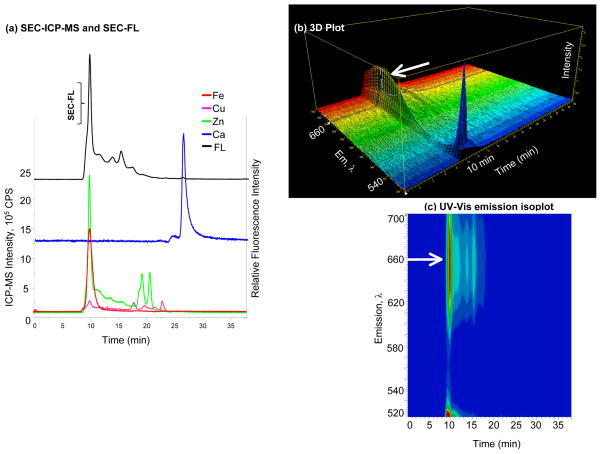

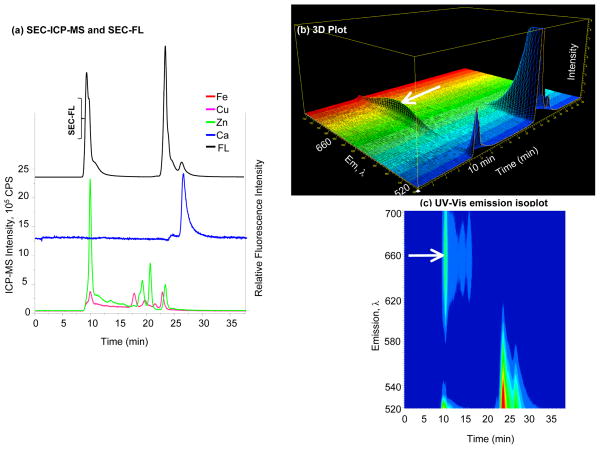

Detection of labile Ca2+

To determine the Ca2+ binding ability of the dyes at resting state, BMCs were treated with four different fluorescent probes, under homeostatic conditions without exogenous stimulation. The SEC-ICP-MS response identified a distinct Ca2+ signal in the LMM region for the BMC lysates as shown in the SEC chromatogram (Figures 3–6) that was comparable to BMCs not exposed to the dyes (Supplementary Figure S1). Though the selected dyes, Calcium Green-1™ AM, Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1, Fura red™ AM and Fluo-4 NW generated a robust SEC-FL response in BMCs, most of the dye fluorescence did not correspond to the labile Ca2+ signal unambiguously detected by SEC-ICP-MS.

Figure 6. Specificity and selectivity of Fluo-4 NW.

(a) SEC-FL and SEC-ICP-MS chromatograms of Fluo-4 NW; Fe, Cu, Zn and Ca signals represented by solid lines belong to the left Y axis, while the SEC-FL signal represented by the black line corresponds to the right Y axis; a small SEC-FL signal is associated with the detection of Ca2+ in the LMM region by ICP-MS; (b) 3D representation of emission wavelength, time and intensity; (c) UV-Vis emission isoplot of Fluo-4 NW; the SEC-FL signal shows a second emission band at 10 min, indicated by the arrow.

Calcium Green-1™ AM generated a small fluorescence peak at 23 min that aligned with the SEC-ICP-MS detection of Cu2+ and Zn2+ in the LMM region (Figure 3a). Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1 produced very weak or negligible SEC-FL responses between 21–23 min that overlapped with low levels of Zn and Cu detected by SEC-ICP-MS (Figure 4a). These SEC-FL signals were a small contribution to the overall fluorescence generated by the dyes.

In BMCs treated with Fura red™ AM, the fluorescence generated in the LMM region was low. A sharp Ca2+ peak was identified in the SEC-ICP-MS trace at ~26.5 min. The only Ca2+ relevant fluorescence response of Fura red™ AM was the appearance of a small SEC-FL signal at ~26.5 min (Figure 5a). In contrast to Fura red™ AM, Fluo-4 NW exhibited a strong fluorescence in the LMM region between 22.5 to 25 min. This fluorescence signal aligned with a major peak for Zn, partially overlapping peak for Cu2+, but only a minor Ca2+ peak. A large Ca2+ peak eluted at the LMM region. Of note, Fluo-4 NW generated an SEC-FL response, albeit small, in response to Ca2+ detection in this region (Figure 6a). Taken together, the SEC-FL contribution of Fura red™ AM and Fluo-4 NW upon non-specific binding was far greater than the fluorescence response produced by Ca2+ binding.

Figure 5. Specificity and selectivity of Fura red™ AM.

(a) SEC-FL and SEC-ICP-MS chromatograms of Fura red™ AM; Fe, Cu, Zn and Ca signals represented by solid lines belong to the left Y axis, while the SEC-FL signal represented by the black line corresponds to the right Y axis; the Ca2+ response is detected by ICP-MS at 26 min; the most intense SEC-FL signal is at HMM, with no Ca2+ response from ICP-MS; (b) 3D representation of emission wavelength, time and intensity; (c) UV-Vis emission isoplot of Fura red™ AM; the SEC-FL signal shows a change in spectral behavior at HMM with a second emission band, indicated by the arrow.

Binding behavior of Ca2+ dyes in high and mid molecular mass regions

To further probe the fluorescence response generated by the dyes, the SEC-FL signals detected by UV-Vis were analyzed throughout the SEC-ICP-MS chromatogram. As with the Zn2+ binding dyes, strong SEC-FL responses were detected with the four Ca2+ binding dyes in the HMM region (≥600 kDa).

Calcium Green-1™ AM has been reported to exhibit a 14 fold increase in fluorescence upon exposure to Ca2+ along with a small shift in emission maximum50. A very strong SEC-FL signal was generated by the dye in the HMM region that corresponded to the detection of Zn by SEC-ICP-MS; additionally the fluorescence signal overlapped partially with Cu and Fe in the void volume (Figure 3a). The response upon binding to molecules of high molecular mass constituted up to ~45% of the total fluorescence generated by the dye in BMC lysates as calculated by peak areas from the SEC-FL chromatogram. Two other SEC-FL peaks were observed for Calcium Green-1™ AM in the mid and LMM regions at the retention times of 20 min and 23 min that did not constitute exchangeable Ca2+ indicated in blue in the SEC-ICP-MS trace. Instead these signals aligned with detection of Zn and Cu at both the retention times. Calcium Green-1™ AM showed an atypical emission spectra with two emission bands in the HMM region, but not in the mid molecular mass region, presented as a 3D projection of the fluorescence emission signals (Figure 3b). The UV-Vis emission isoplots offer an alternative way to view the emission behavior of the dye (Figure 3c). These data indicate that for imaging Ca2+ using Calcium Green-1™ AM, acquisition of multi-wavelength data would be desirable.

In the HMM region, Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1 exhibited an SEC-FL response that aligned with SEC-ICP-MS signals for both Zn and Cu, and partially with that of Fe (Figure 4a). Three additional SEC-FL signals were observed in the mid molecular mass regions, at ~12, 15 and 19 min, again, corresponding to the identification of Zn and Cu, but an Fe peak was not detected in this region. Of note, the intensity of SEC-FL response at 19 min containing two larger Zn peaks and a smaller Cu peak, identified as containing metallothionein (Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S2), was strong and comparable to the fluorescence response of the dye at 9 min in the HMM region. The Ca signal detected by SEC-ICP-MS occurred almost entirely in the far LMM region, but none of the SEC-FL responses of the dye resulted from Ca2+ detection. These data indicate that the fluorescence generated by Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1 under homeostatic conditions may result from non-specific binding to Zn, Cu and Fe. Similar to Calcium Green-1™ AM, the SEC-FL response of Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1 did manifest a change in emission spectral behavior upon metal recognition as observed in the 3D fluorescence projection and UV-Vis emission isoplot (Figures 4b and 4c).

Fura Red™ responded with multiple SEC-FL signals in the HMM to mid molecular mass regions, however, the SEC-FL signal observed at the Ca2+ elution time shown by SEC-ICP-MS was negligible (Figure 5a). The SEC-FL emission in the HMM region at 10 min corresponded to Zn and partially overlapped with that of Fe. Though the response of the dye was most intense at ~600 kDa, several lower intensity fluorescence signals were observed in the mid molecular mass regions between 11 min to 19 min where multiple Zn and Cu peaks were detected. This Ca2+ dye presented two distinct emission bands at 530 nm and 660 nm upon interacting with metals in the HMM region, shown in the 3D projection and UV-Vis emission isoplot (Figures 5b and 5c) similar to those observed with Calcium Green-1™ AM.

Fluo-4 has an improved structural chemistry compared to Fluo-3, and the modification enhances fluorescence intensity upon Ca2+ binding50. This dye has been used extensively in studies ranging from imaging cell populations51 to high throughput drug screening assays for analysis of Ca2+ flux52. The fluorescence response of this dye was detected in the HMM region at ~10 min corresponding to chelation of non-Ca2+ containing species, for the most part, Zn and Cu (Figure 6a). Three of the four Ca2+ binding dyes tested, including Fluo-4 NW displayed a shift in the emission maxima, compared with the reported emission spectra, with a second band at 660 nm in the HMM region upon non-specific metal detection (Figure 6b and 6c). Collectively, under the physiological resting state of Ca2+ in BMCs, the dyes exhibited a relatively high fluorescence intensity upon non-specific and non-selective binding to metals in the HMM region.

Fluorescence response of Ca2+ binding dyes under stimulation conditions

An application of Ca2+ imaging dyes is to follow Ca2+ changes as a result of enhanced influx or release from intracellular stores upon stimulation. Therefore, in Ca2+ imaging studies, the fluorescence response of the dye prior to stimulation is corrected by setting the value to zero. The selected Ca2+ binding dyes produced a series of mid molecular mass and HMM SEC-FL signals, unrelated to Ca2+ under homeostatic conditions. To investigate whether the lack of Ca2+ recognition was due to an inability of the dye to permeate intracellular organelles that store the metal, cells were stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin to trigger Ca2+ release from organelles and to enhance influx53,54. The Ca2+ related fluorescence response, post-stimulation, was compared with the resting control for two of the four dyes.

Exposure to PMA and ionomycin generated an increased influx of the metal, as is evident from the enhanced Ca2+ signal intensity observed in the SEC-ICPMS chromatogram (Figures 7 and 8). However, Fura Red™ staining of stimulated BMCs did not result in a corresponding substantial increase in the fluorescence signal in the region where Ca2+ was detected by ICP-MS (Figures 7a–7c).

Figure 7. Specificity and selectivity of Fura red™ AM with exogenous stimulation.

(a) SEC-FL and SEC-ICP-MS chromatograms of Fura red™ AM in BMCs exposed to PMA and ionomycin stimulation; Fe, Cu, Zn and Ca signals represented by solid lines belong to the left Y axis, while the SEC-FL signal represented by the black line corresponds to the right Y axis; the Ca2+ response detected by ICP-MS at 26 min shows an increase upon stimulation; a strong SEC-FL signal is observed at HMM, with no Ca2+ response from ICP-MS; (b) 3D representation of emission wavelength, time and intensity; (c) UV-Vis emission isoplot of Fura red™ AM; the SEC-FL signal shows a change in spectral behavior at HMM with a second emission band, indicated by the arrow.

Figure 8. Specificity and selectivity of Fluo-4 NW with exogenous stimulation.

(a) SEC-FL and SEC-ICP-MS chromatograms of Fluo-4 NW in BMCs exposed to PMA and ionomycin stimulation; Fe, Cu, Zn and Ca signals represented by solid lines belong to the left Y axis, while the SEC-FL signal represented by the black line corresponds to the right Y axis; exogenous stimulation led to a small increase in SEC-FL signal associated with the detection of Ca2+ in the LMM region by ICP-MS, but led to a larger increase in fluorescence in the HMM and mid molecular mass regions; (b) 3D representation of emission wavelength, time and intensity; (c) UV-Vis emission isoplot of Fluo-4 NW; the dye exhibits a second emission band at 660 nm in the HMM region at 10 min, indicated by the arrow.

Next, we evaluated the behavior of Fluo-4 NW upon stimulation of BMCs to induce Ca2+ flux. PMA and ionomycin effectively enhanced the intensity of the SEC-ICP-MS response for Ca2+ at the LMW region (Figure 8). For the specific case of Fluo-4 NW, a small enhancement in the SEC-FL response was seen upon stimulation, representing a 20% peak area increase at the region where Ca2+ was detected compared to the resting cells (Figures 8a–8c). This response was the only relevant signal generated by the dye upon binding Ca2+. However, stimulation of BMCs led to an elevated SEC-FL response by Fluo-4 NW at 9 min and 23 min in the HMM and LMM regions respectively, that did not correspond to Ca2+, but to Zn, Cu and Fe. The enhanced fluorescence of the dye in the presence of an exogenous stimulus is a confounding factor in confocal imaging, flow cytometry or high throughput analysis. The net increase in the fluorescence response above baseline, obtained upon stimulation, may not necessarily correspond to specific alterations in Ca2+ flux triggered by the stimulus under study, but may result from non-specific interactions of the dye with other metals.

Discussion

There is an increasing interest in the use of fluorescent probes for Zn and Ca analysis in biological systems. However, the metal interactions and binding behavior of these dyes in a complex cellular environment have been sparingly investigated. We selected commonly used metal imaging probes for Zn and Ca and obtained reproducible UV-Vis, FL and ICPMS signals by staining a BMC cell line using typical conditions employed for confocal imaging and flow cytometry. Lysis of the cells with 0.1% SDS on ice and immediate introduction to the HPLC with UV-Vis, SEC-FL, and ICP-MS detection was found to be an excellent way to track the fluorescent response of each dye, based not on the optical signal obtained as in imaging experiments, but on the association of the dyes with different metals and the varying molecular masses in the lysate fractions. With this approach using the three tandem detectors, it was possible to observe interaction of the dyes with metal-bound entities across a range of molecular masses. Most of the fluorescence responses did not result from labile metal detection in the LMM region. A summary of the fluorescence behavior of the dyes is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of selectivity results for the Zn2+ and Ca2+ binding probes. The signal at different molecular mass regions is represented by; + = 1–20%, ++ = 21–49%, +++ = >50% of total fluorescence signal.

| Name of the probe | Target | SEC-FL signal at HMM | SEC-FL signal at mid-MM | SEC-FL signal at LMM | % of the total SEC- FL signal at LMM | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zinpyr-1 | Zn2+ | + | − | +++ | >70 | |

| FluoZin™-3 AM | Zn2+ | +++ | + | + | <10 | |

| Newport Green™ DCF | Zn2+ | + | − | +++ | >80 | SEC-FL signals without Zn signal at LMW |

| Zinquin ethyl ester | Zn2+ | +++ | − | + | <2% | |

| Calcium Green-1™ AM | Ca2+ | +++ | ++ | + | <5% | No SEC-FL matched with ICP MS-Ca signal |

| Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1 | Ca2+ | ++ | ++ | + | 10% | No SEC-FL matched with ICP MS-Ca signal |

| Fura red™ AM | Ca2+ | +++ | ++ | + | <5% | % of Ca-SEC-FL signal does not increase upon stimulation |

| Fluo-4 NW | Ca2+ | ++ | +++ | + | 15 % |

The pool of exchangeable Zn2+ in cells appeared in the LMM region, however, the Zn2+ binding dyes, except Zinpyr-1, exhibited intense fluorescent signals in the HMM fractions. For the particular case of Newport Green™ DCF, the two strongest fluorescent signals at LMM region were not related to Zn or any other metal analyzed. While Zinpyr-1 generated a response in the LMM region, FluoZin™-3 AM was weakly responsive to labile metal and fluorescence from Zinquin ethyl ester largely resulted from recognition of metals in the HMM region. The chemical properties of small molecule Zn2+ probes may influence their propensity to fluoresce in the HMM region. Modification of the dye structure to facilitate entry into cells often results in the dye being trapped in vesicles or organelles after enzymatic cleavage by hydrolases55. One such example is the Zinquin ethyl ester that complexes with Zn bound proteins and is retained intracellularly within vesicles56. The SEC-FL response of Zn2+ dyes in the HMM region may therefore represent dye-metal complexes retained into incompletely lysed intracellular vesicles that elute in the void volume of the SEC chromatogram. These data suggest that Zn2+ dyes not only recognize the labile Zn2+ fraction, but also respond effectively to Zn bound to higher molecular masses in an intracellular environment.

The four Ca2+ dyes tested exhibited very weak fluorescence in response to exchangeable Ca2+ under homeostatic conditions. In fact a majority of the registered fluorescence responses from the Ca2+ dyes were in the mid molecular mass to HMM regions, and these were associated to Zn, Cu and Fe. It is possible to identify non-specific metal binding by the Ca2+ dyes in microscopic applications by observing the changes in the fluorescence emission spectra. Intracellular Ca2+ ions may localize to organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria16,28. This behavior may have resulted in non-specific and non-selective recognition of metal ions such as Zn, Cu, and Fe in the cytosol by the Ca2+ binding dyes. In response to a stimulus, Ca2+ flux is triggered and leads to enhanced import of the metal from extracellular spaces and release from organelles57,58. Therefore, we analyzed response of dyes in the presence of a Ca2+ ionophore54,59. While stimulation enhanced Ca2+ as detected by SEC-ICP-MS in the LMM region, the SEC-FL produced by the dyes in this region remained the smallest signal, and did not increase in proportion to the additional Ca2+ released.

Specific detection of Ca2+ by fluorescent indicators is hampered by the presence of heavy metals, as they fluoresce strongly upon heavy metal binding60. It has been suggested that the use of the metal chelator NNNN-tetrakis (2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (TPEN) in cells to deplete heavy metal traces permits more accurate detection of Ca2+. TPEN however, chelates Zn with strong affinity, and also binds Fe in cells61. Chelation of Zn and Fe to analyze Ca2+ flux in cells may lead to perturbations of numerous critical homeostatic cellular functions that depend on the availability of these metals62,63. In this context, the fluorescence response of Ca2+ binding dyes has been tested in screening assays for drugs that modulate G-protein coupled receptors activity64 and to test drug resistant and sensitive cell lines65. The high SEC-FL response generated by the four Ca2+ dyes due to non-specific metal detection and non-selective binding to HMM species, under resting as well as stimulated conditions indicates that the net fluorescence signal contribution in these assays may not exclusively result from alterations in the intracellular Ca2+ pool.

We have tested the fluorescence response of Zn2+ and Ca2+ binding dyes using a bone marrow macrophage cell line. The relative metal composition, concentrations of each metal and their distribution may vary among other cell lines as well as primary cell types. These variations may lead to differential behavior of dyes depending on the cell type under examination, and a particular dye may be suited to imaging specific cell types. Nonetheless, a majority of the dyes have been widely applied in Zn2+ or Ca2+ analysis in phenotypically distinct cell populations such as immune cells23,25, cardiomyocytes27, fibroblasts66, and neurons30,67.

Conclusion

This study has addressed an important aspect in the use of small molecule fluorescent dyes for the detection of metals in a cellular environment. We analyzed the fluorescence behavior of commonly used Zn2+ and Ca2+ indicators to investigate their specificity for a particular metal ion and selectivity for one or more forms of a given metal in an intracellular environment. In the case of Zn2+ indicators, Zinpyr-1 fluoresced effectively in response to labile Zn2+, but FluoZin™-3 AM, Newport Green™ DCF and Zinquin ethyl ester were strongly responsive to metals bound to larger, complex biomolecules and weakly or negligibly responded to exchangeable Zn2+. In studies with Ca2+ indicators, the four dyes tested, Calcium Green-1™ AM and Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1, Fura red™ AM and Fluo-4 NW strongly fluoresced in response to larger bio-molecular complexes containing Zn, Cu and Fe. A majority of the cellular Ca2+ occurred in the labile form, but the Ca2+ binding dyes responded sub-optimally to this metal under both, resting and Ca2+ stimulated conditions. Collectively, the data obtained from analysis using a particular cell line indicate that fluorescence generated by chemical probes within cells may result from non-selective binding to labile and protein bound as well as membrane bound metals and/or from non-specific affinity for other divalent cations. These results emphasize that the use of metal binding dyes in bio-imaging applications should be supported by additional approaches to derive conclusions regarding the modulation of metals in a cellular environment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Agilent Technologies for their continued support with chromatography and mass spectrometry instrumentation as well as NIH for support by grants # AI-094971, AI-106269 and a Merit Review from Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Lynch CJ, Patson BJ, Goodman SA, Trapolsi D, Kimball SR. Zinc stimulates the activity of the insulin- and nutrient-regulated protein kinase mTOR. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology And Metabolism. 2001;281:E25–E34. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.1.E25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang SJ, Gao C, Chen BA. Advancement of the study on iron metabolism and regulation in tumor cells. Chin J Cancer. 2010;29:451–455. doi: 10.5732/cjc.009.10716. 1000-467X201004451 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crea T, Guerin V, Ortega F, Hartemann P. Zinc and the immune system. Ann Med Interne (Paris) 1990;141:447–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraker PJ, King LE. Reprogramming of the immune system during zinc deficiency. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:277–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rofe AM, Philcox JC, Coyle P. Activation of glycolysis by zinc is diminished in hepatocytes from metallothionein-null mice. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2000;75:87–97. doi: 10.1385/BTER:75:1-3:87. BTER:75:1-3:87 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azriel-Tamir H, Sharir H, Schwartz B, Hershfinkel M. Extracellular zinc triggers ERK-dependent activation of Na+/H+ exchange in colonocytes mediated by the zinc-sensing receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51804–51816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406581200. M406581200 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellomo EA, Meur G, Rutter GA. Glucose regulates free cytosolic Zn(2) concentration, Slc39 (ZiP), and metallothionein gene expression in primary pancreatic islet beta-cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:25778–25789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.246082. M111.246082 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haase H, Rink L. Signal transduction in monocytes: the role of zinc ions. Biometals. 2007;20:579–585. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hood MI, Skaar EP. Nutritional immunity: transition metals at the pathogen-host interface. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:525–537. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2836. nrmicro2836 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maret W. Metals on the move: zinc ions in cellular regulation and in the coordination dynamics of zinc proteins. BioMetals. 2011;24:411–418. doi: 10.1007/s10534-010-9406-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanz-Medel A, Montes-Bayon M, Luisa Fernandez Sanchez M. Trace element speciation by ICP-MS in large biomolecules and its potential for proteomics. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2003;377:236–247. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2082-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Domaille DW, Que EL, Chang CJ. Synthetic fluorescent sensors for studying the cell biology of metals. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:168–175. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.69. nchembio.69 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsien RY. A non-disruptive technique for loading calcium buffers and indicators into cells. Nature. 1981;290:527–528. doi: 10.1038/290527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devinney MJ, 2nd, Reynolds IJ, Dineley KE. Simultaneous detection of intracellular free calcium and zinc using fura-2FF and FluoZin-3. Cell Calcium. 2005;37:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.10.003. S0143-4160(04)00171-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyrc KL, Bownik JM, Goldberg MP. Ionic selectivity of low-affinity ratiometric calcium indicators: mag-Fura-2, Fura-2FF and BTC. Cell Calcium. 2000;27:75–86. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0092. S0143-4160(99)90092-1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pacher P, Csordas P, Schneider T, Hajnoczky G. Quantification of calcium signal transmission from sarco-endoplasmic reticulum to the mitochondria. J Physiol. 2000;529(Pt 3):553–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00553.x. PHY_11099 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zinc and the immune system. TreatmentUpdate. 2001;13:1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukada T, Yamasaki S, Nishida K, Murakami M, Hirano T. Zinc homeostasis and signaling in health and diseases: Zinc signaling. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2011;16:1123–1134. doi: 10.1007/s00775-011-0797-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chasapis CT, Loutsidou AC, Spiliopoulou CA, Stefanidou ME. Zinc and human health: an update. Arch Toxicol. 2012;86:521–534. doi: 10.1007/s00204-011-0775-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colvin RA, Holmes WR, Fontaine CP, Maret W. Cytosolic zinc buffering and muffling: their role in intracellular zinc homeostasis. Metallomics. 2010;2:306–317. doi: 10.1039/b926662c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murakami M, Hirano T. Intracellular zinc homeostasis and zinc signaling. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1515–1522. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00854.x. CAS854 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wellenreuther G, Cianci M, Tucoulou R, Meyer-Klaucke W, Haase H. The ligand environment of zinc stored in vesicles. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;380:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.074. S0006-291X(09)00116-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitamura H, et al. Toll-like receptor-mediated regulation of zinc homeostasis influences dendritic cell function. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:971–977. doi: 10.1038/ni1373. ni1373 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devergnas S, et al. Differential regulation of zinc efflux transporters ZnT-1, ZnT-5 and ZnT-7 gene expression by zinc levels: a real-time RT-PCR study. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:699–709. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.024. S0006295204003168 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamasaki S, et al. Zinc is a novel intracellular second messenger. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:637–645. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702081. jcb.200702081 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zalewski PD, et al. Video image analysis of labile zinc in viable pancreatic islet cells using a specific fluorescent probe for zinc. J Histochem Cytochem. 1994;42:877–884. doi: 10.1177/42.7.8014471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golebiewska U, Scarlata S. Measuring fast calcium fluxes in cardiomyocytes. J Vis Exp. 2011:e3505. doi: 10.3791/3505. 3505 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidson SM, Duchen MR. Imaging mitochondrial calcium signalling with fluorescent probes and single or two photon confocal microscopy. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;810:219–234. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-382-0_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finch EA, Augustine GJ. Local calcium signalling by inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate in Purkinje cell dendrites. Nature. 1998;396:753–756. doi: 10.1038/25541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barreto-Chang OL, Dolmetsch RE. Calcium imaging of cortical neurons using Fura-2 AM. J Vis Exp. 2009 doi: 10.3791/1067. 1067 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lohr C. Monitoring neuronal calcium signalling using a new method for ratiometric confocal calcium imaging. Cell Calcium. 2003;34:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00105-2. S0143416003001052 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi A, Camacho P, Lechleiter JD, Herman B. Measurement of Intracellular Calcium. Physiological Reviews. 1999;79:1089–1125. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomat E, Lippard SJ. Imaging mobile zinc in biology. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.12.010. S1367-5931(09)00202-6 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L, Qin W, Tang X, Dou W, Liu W. Development and applications of fluorescent indicators for Mg2+ and Zn2+ J Phys Chem A. 2011;115:1609–1616. doi: 10.1021/jp110305k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reynolds IJ. Fluorescence detection of redox-sensitive metals in neuronal culture: focus on iron and zinc. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1012:27–36. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gee KR, Zhou ZL, Ton-That D, Sensi SL, Weiss JH. Measuring zinc in living cells. A new generation of sensitive and selective fluorescent probes. Cell Calcium. 2002;31:245–251. doi: 10.1016/S0143-4160(02)00053-2. S0143-4160(02)00053-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hackam DJ, et al. Regulation of Phagosomal Acidification: DIFFERENTIAL TARGETING OF Na+/H+EXCHANGERS, Na+/K+-ATPases, AND VACUOLAR-TYPE H+-ATPases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:29810–29820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Madshus IH. Regulation of intracellular pH in eukaryotic cells. Biochem J. 1988;250:1–8. doi: 10.1042/bj2500001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kovacsovics-Bankowski M, Clark K, Benacerraf B, Rock KL. Efficient major histocompatibility complex class I presentation of exogenous antigen upon phagocytosis by macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:4942–4946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.4942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bin B-H, et al. Biochemical Characterization of Human ZIP13 Protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:40255–40265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.256784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ichii H, et al. A Novel Method for the Assessment of Cellular Composition and Beta–Cell Viability in Human Islet Preparations. American journal of transplantation. 2005;5:1635–1645. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu MJ, et al. ZIP8 regulates host defense through zinc-mediated inhibition of NF-kappaB. Cell Rep. 2013;3:386–400. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.009. S2211-1247(13)00016-8 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cadosch D, Meagher J, Gautschi OP, Filgueira L. Uptake and intracellular distribution of various metal ions in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells detected by Newport Green DCF diacetate ester. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;178:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.12.008. S0165-0270(08)00683-3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao J, Bertoglio BA, Devinney MJ, Jr, Dineley KE, Kay AR. The interaction of biological and noxious transition metals with the zinc probes FluoZin-3 and Newport Green. Anal Biochem. 2009;384:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.09.019. S0003-2697(08)00605-2 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaltenberg J, et al. Zinc signals promote IL-2-dependent proliferation of T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:1496–1503. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kiedrowski L. Cytosolic zinc release and clearance in hippocampal neurons exposed to glutamate--the role of pH and sodium. J Neurochem. 2011;117:231–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu T, Fang LY, Xie X. Development of a universal high-throughput calcium assay for G-protein- coupled receptors with promiscuous G-protein Galpha15/16. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29:507–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bailey S, Macardle PJ. A flow cytometric comparison of Indo-1 to fluo-3 and Fura Red excited with low power lasers for detecting Ca(2+) flux. J Immunol Methods. 2006;311:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.02.005. S0022-1759(06)00047-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Indicators for Ca2+, Mg2+, Zn2+ and Other Metal Ions, Molecular Probes Handbook. Life Technologies; NY: Chapter 19 Section 19.11–Section 19.13. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spinelli KJ, Gillespie PG. Monitoring intracellular calcium ion dynamics in hair cell populations with Fluo-4 AM. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051874. PONE-D-12-29551 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu K, et al. A multiplex calcium assay for identification of GPCR agonists and antagonists. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2010;8:367–379. doi: 10.1089/adt.2009.0245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schulte EE. Understanding Plate Nutrients. Soil and Applied Zinc. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lagast H, Pozzan T, Waldvogel FA, Lew PD. Phorbol myristate acetate stimulates ATP-dependent calcium transport by the plasma membrane of neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1984;73:878–883. doi: 10.1172/JCI111284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Terai T, Nagano T. Fluorescent probes for bioimaging applications. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.08.007. S1367-5931(08)00122-1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Snitsarev V, et al. Fluorescent detection of Zn(2+)-rich vesicles with Zinquin: mechanism of action in lipid environments. Biophys J. 2001;80:1538–1546. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76126-7. S0006-3495(01)76126-7 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muallem S, Pandol S, Beeker T. Hormone-evoked calcium release from intracellular stores is a quantal process. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264:205–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Streb H, Irvine R, Berridge M, Schulz I. Release of Ca2+ from a nonmitochondrial intracellular store in pancreatic acinar cells by inositol-1, 4, 5-trisphosphate. Nature. 1983;306:67–69. doi: 10.1038/306067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoshida S, Plant S. Mechanism of release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores in response to ionomycin in oocytes of the frog Xenopus laevis. J Physiol. 1992;458:307–318. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Snitsarev VA, McNulty TJ, Taylor CW. Endogenous heavy metal ions perturb fura-2 measurements of basal and hormone-evoked Ca2+ signals. Biophys J. 1996;71:1048–1056. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79305-0. S0006-3495(96)79305-0 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shumaker DK, Vann LR, Goldberg MW, Allen TD, Wilson KL. TPEN, a Zn2+/Fe2+ chelator with low affinity for Ca2+, inhibits lamin assembly, destabilizes nuclear architecture and may independently protect nuclei from apoptosis in vitro. Cell Calcium. 1998;23:151–164. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(98)90114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cousins RJ, Liuzzi JP, Lichten LA. Mammalian zinc transport, trafficking, and signals. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24085–24089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600011200. R600011200 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu Y, Kovacevic Z, Richardson DR. Tuning cell cycle regulation with an iron key. Cell cycle. 2007;6:1982–1994. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.16.4603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hansen KB, Brauner-Osborne H. FLIPR assays of intracellular calcium in GPCR drug discovery. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;552:269–278. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-317-6_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.DeBernardi MA, Brooker G. High-content kinetic calcium imaging in drug-sensitive and drug-resistant human breast cancer cells. Methods Enzymol. 2006;414:317–335. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)14018-5. S0076-6879(06)14018-5 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.St Croix CM, et al. Nitric oxide-induced changes in intracellular zinc homeostasis are mediated by metallothionein/thionein. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L185–192. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00267.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baker BJ, et al. Imaging brain activity with voltage- and calcium-sensitive dyes. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2005;25:245–282. doi: 10.1007/s10571-005-3059-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.