Abstract

Introduction

Same-sex serodiscordant male dyads represent a high priority risk group, with approximately one to two-thirds of new HIV infections among MSM attributable to main partnerships. Early initiation and adherence to highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) is a key factor in HIV prevention and treatment; however, adherence to HAART in the U.S. is low, with poor retention throughout the continuum of care. This study examines MSM's perceptions of dyadic HIV treatment across the continuum of care to understand preferences for how care may be sought with a partner.

Methods

We conducted five focus group discussions (FGDs) in Atlanta, GA with 35 men who report being in same-sex male partnerships. Participants discussed perceptions of care using scenarios of a hypothetical same-sex male couple who recently received serodiscordant or seroconcordant positive HIV results. Verbatim transcripts were segmented thematically and systematically analyzed to examine patterns in responses within and between participants and FGDs.

Results

Participants identified the need for comprehensive dyadic care and differences in care for seroconcordant positive versus serodiscordant couples. Participants described a reciprocal relationship between comprehensive dyadic care and positive relationship dynamics. This combination was described as reinforcing commitment, ultimately leading to increased accountability and treatment adherence.

Discussion

Results indicate that the act of same-sex male couples “working together to reach a goal” may increase retention to HIV care across the continuum if care is comprehensive, focuses on both individual and dyadic needs, and promotes positive relationship dynamics.

Keywords: MSM, Dyadic HIV Care, Same-Sex Male Relationships, HAART Adherence

Introduction

Same-sex serodiscordant male dyads represent a high priority HIV risk group; recent data show that approximately one to two-thirds of new HIV infections among MSM are attributed to main sexual partners.1,2 Early initiation and adherence to highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) is a key factor in HIV prevention and treatment; however, the average rate of adherence in the U.S. is below optimal levels necessary to achieve viral suppression.3,4 Low adherence occurs across a continuum of care;5 recent analyses have found that only 77% of all people living with HIV in the U.S. are linked to care and 51% remain in care, with only 28% of all HIV-positive people achieving viral suppression.4 There are dyadic benefits to early HAART initiation and adherence; viral suppression improves health outcomes and reduces the likelihood of transmission to an HIV-negative person.6-12 Despite evidence indicating that male same-sex dyads may benefit from improved HAART adherence, no HIV interventions currently exist to address dyadic needs across the care continuum.

Previous research suggests that dyadic care has the potential to significantly impact the behaviors of same-sex male dyads by fostering mutual HIV-specific social support13-19 and promoting positive relationship dynamics.20-24 Johnson et al. found that increased positive appraisal of a same-sex male relationship is positively associated with increased self-report of HAART adherence.23 A partner's reporting of greater relationship commitment was also positively associated with reduced virological load for their HIV-positive partner, indicating that positive relationship appraisal from both partners is important for HAART adherence.23

Most research examining the benefits of dyadic HIV care is aimed at heterosexual couples;25 however, there is some evidence that dyadic interventions may also be useful for MSM.26-29 Couples voluntary HIV counseling and testing (CVCT) is a dyadic intervention, originally created for African heterosexuals, in which partners receive information and counseling together both before and after testing for HIV status. Risk ascertainment and risk-reduction counseling are catered specifically to the couple's needs and serostatus.30 Research with heterosexual serodiscordant couples demonstrated that CVCT is an effective intervention for reducing HIV transmission, increasing consistent condom use, and reducing sexual risk-taking.30-34 Though studies showing the efficacy of CVCT among MSM have not been conducted, Stephenson et al. identified MSM's willingness to utilize CVCT in seven countries, including the U.S.27,28 In a randomized controlled trial, Sullivan et al. also found that CVCT is a safe and acceptable intervention for MSM.35 Remien et al. conducted a randomized controlled trial examining a dyadic adherence intervention among HIV-positive people in heterosexual and same-sex serodiscordant relationships who had suboptimal adherence at baseline.26 This intervention was successful in improving adherence by promoting mutual partner support, improving communication between partners, educating partners about adherence importance and patterns, and building confidence in their relationship and ability to adhere to treatment.26

Though some research shows that dyadic HIV interventions may be beneficial to MSM, we do not know what MSM's preferences are for receiving care as a couple. The purpose of this study is to investigate the potential for creating a dyadic continuum of care that begins with CVCT and continues through linkage and retention in care.

Methods

This study was approved by Emory University's Institutional Review Board. Five focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with GBM in same-sex male relationships in Atlanta, Georgia from March to May 2013. Each FGD lasted approximately 90 minutes and included 6-10 GBM. GBM participated in FGDs individually; both partners in a same-sex relationship could participate in the study only if they were in separate FGDs. Eligibility criteria included: aged ≥18 years, identifying as gay or bisexual, having a main partnership with a man lasting ≥3 months, and living in the metropolitan area of Atlanta, GA. Having a main partnership was determined if a man answered “yes” to the question: “Are you currently in a relationship with a man who you feel committed to above all others and with whom you have ever had sex? Some people might call this person a boyfriend, life partner, husband, or significant other.” Three months does not necessarily indicate a long-term relationship; since opinions were provided using a hypothetical scenario rather than personal relationships, a longer relationship length was not necessary for participation.

GBM had previously participated in cohort studies at Emory University, which used venue-based sampling (VBS) in Atlanta, GA. VBS is derived from time-space sampling and involves recruitment within predetermined blocks of time at previously-identified venues at which hard-to-reach populations frequently congregate.36 All potential participants (n=1,431) were contacted via email to complete a screening survey. Of the 261 people who completed the survey, all 94 eligible men were contacted for participation. This study also employed a snowball method;37 FGD participants referred other potential participants to the study. All participant-driven recruitments also completed a screening survey to ensure eligibility prior to participation. GBM were compensated $30 for participation.

Participants discussed reactions to scenarios of a hypothetical same-sex male couple who recently received serodiscordant HIV results (FGD1-FGD2) or seroconcordant positive HIV results (FGD3-FGD5); this scenario involved discussion of a committed, long-term partnership. Participants shared opinions on how this couple should receive care at each step across the continuum of care, starting after the awareness of an HIV infection, including: linkage to care, retention in care, initiating HAART, and HAART adherence.5

All FGDs were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Analysis was completed using principles of grounded theory38 and with the aid of MAXqda, version 10 (Verbi Software, Berlin, Germany), a qualitative data analysis program. Multiple close readings of the transcripts were completed in order to identify major themes that were discussed across all FGDs. Codes were applied to all textual data based on reoccurring themes in the transcripts (Table 1). Segments of data were retrieved based on individual codes and intersections of codes to compare and contrast reoccurring themes within and between FGDs and FGD participants. Agreement and disagreement among participants were examined through close readings of segmented data. Key statements that identified common ideas and unique perspectives were chosen in order to best represent the reoccurring themes present in the data.

Table 1. Code definitions.

| Acceptance | Acceptance of HIV, the new lifestyle, and the need to take medication; includes both individual acceptance and acceptance as a couple |

| Health Status | Concordant partners' health status, how differences/similarities in health status could impact the relationship; includes differences in regimens, T cells, and response to medication |

| Medication | Experience of taking medication, side effects, adherence, support needs for taking medication |

| Logistics | Access to care, length of appointments, doctor space, location/distance, carpooling, publicizing/advertising couples' services, acceptance/non-acceptance of couples' services at the facility, knowledge regarding legality of partner's presence |

| Appointment Attendance | Factors that impact keeping or skipping doctor appointments, doctor appointments as part of a routine |

| Accountability | Being accountable for taking medication and attending appointments; includes personal accountability and how a partner's support can impact accountability, includes reminders to take medication and going to appointments |

| Privacy | Issues of confidentiality, disclosure, being able to openly share with the doctor; how the doctor shares information with partners or family members in terms of confidentiality |

| Money | Money, insurance, paying for treatment, employment, economic impact |

| Education | Educational/information/awareness needs, how doctors should provide information, receiving/interpreting information individually in a visit vs. together, any reference of how having education/no education impacts the experience of receiving treatment |

| Relationship Dynamics | Commitment, communication between partners, Independence vs. dependence, impact of dyadic characteristics (emotional, demographic, medical), fears/resentment/anger/jealousy/blame between partners and impact on relationship dynamic and ability to get care, “infidelity”, being a “burden,” the caretaker role |

| Partner Support | Support provided by a partner, support needs from partner; also include not needing support from partner |

| Emotional Support | Emotional support (“mental support”) needs in general and discussions of emotional strain in general; this can be provided by partner or any other source of support |

| Other Resources | Discussion of types of support (other than partner support), including: support groups, community organizations, family, friends, religion, etc. |

| Doctor Rapport | Communication with doctor, relationship with doctor, LGBT friendliness, cultural competence, comfort with doctor, doctor specialty/knowledge of HIV, discussions of how to navigate the doctors' attention in a visit when individual vs. with partner, dynamic of how doctor relationship changes when the doctor is treating two people vs. one, triad vs. dyad |

| Holistic Care | Discussions of needs from medical system beyond just basic HIV treatment (e.g. case managers, counseling, “one stop shop kind of facility”), discussions of aspects of health needs beyond what is typically provided by an HIV care provider |

| Risk Behaviors/Reduction | Condom use, alcohol/drugs, “self-destructive” behaviors, keeping the negative partner negative |

| Personal Responsibility | Discussions of personal responsibility in terms of receiving and adhering to HIV care, including personal motivation to receive care |

| Mental Health | Discussions of either partner's personal mental health state, including: depression, self-acceptance, fear, self-esteem etc. |

| Stigma | Discussions of stigma regarding HIV |

Results

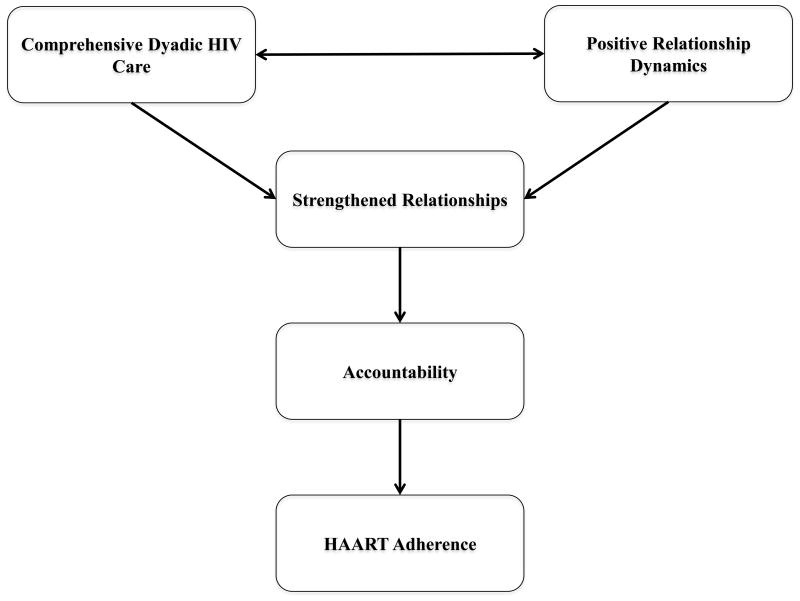

A total of 35 GBM participated in this study; demographics based on age, race, sexual orientation, and relationship length are described in Table 2. Participants described what dyadic HIV care would look like for both seroconcordant positive and serodiscordant same-sex male couples. There was variation between participants within and between FGDs when discussing preferences for dyadic care vs. individual care, with greater variation occurring among FGDs using an example of a seroconcordant positive couple. Themes in the FGDs addressed comprehensive dyadic care, relationship dynamics, strengthening relationships, and accountability and adherence; all themes were discussed in terms of dyadic care and the impact on adherence. Connections were made between themes (Figure 1); results are summarized based on benefits and challenges of dyadic care in Table 3.

Table 2. Participant Demographics for Race, Sexual Orientation, and Relationship Length.

| Mean | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.1 | 26-67 |

| n | % | |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian/White | 11 | 31.4 |

| African American/Black | 20 | 57.1 |

| Other | 5 | 14.3 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Gay/Homosexual | 33 | 94.3 |

| Bisexual | 2 | 5.7 |

| Relationship Length | ||

| 3-6 months | 2 | 5.7 |

| 6-12 months | 8 | 22.9 |

| 1-4 years | 15 | 42.9 |

| ≥5 years | 10 | 28.6 |

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework Examining Impact of Dyadic Care on HAART Adherence for Same-Sex Male Partnerships.

Table 3. Overview of GBM's Perceptions of Benefits and Challenges of Dyadic Care for Same-Sex Male Couples.

| Benefits of Dyadic Care | Challenges of Dyadic Care | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serodiscordant | Concordant Positive | Serodiscordant | Concordant Positive | |

| Comprehensive Dyadic Care “The care network of are you feeling down and you need to talk to someone else that's not just a lab coat?” | Can access comprehensive care together to prevent seroconversion: “I would want some sort of sex plan and maybe also meet with a counselor [together]” | Partners can motivate each other to remain optimistic with HIV medications when one or both partners experience negative side effects. | Different needs: “So, [one partner] being negative needs… to make sure [he] stays negative, making sure that if this relationship is right for [him] that [he] want to stay in that relationship… And then [the positive partner] though doesn't have somebody that can relate firsthand.” | Different experiences with HIV: “When you go to see your doctor, you need that attention just for yourself and how can you get that attention that you need if it's two of y'all in the room? And you're not going to be able to get that quality time that you need to understand things for you because y'all bodies are different.” |

| Relationship Dynamics |

Honesty and Communication: “When I had the partner there it was nothing to hide…There is nothing to hide to them and there's nothing to hide to the dr.” |

Privacy and Confidentiality: “Have some questions and things that he might not be comfortable asking if his partner is sitting there” |

||

| Strengthening –Relationships |

Establishes Empathy: “If one partner goes, you establish only sympathy because the other partner doesn't understand what the doctor said. But if both partners go, you established empathy… speaking to both parties will establish the connection between those two and so that it will help strengthen the bonds of the relationship.” |

If relationship dynamics are not positive and do not work simultaneously with comprehensive dyadic care, then a strengthened relationship will not be established. | ||

|

Collaboration: “work together to reach a goal”; “Now they both know they're not in it alone” | ||||

| Accountability and Adherence | Adherence was perceived as an act of commitment to one's partner: “By [the positive partner] taking his drugs, he is showing the [negative partner] that he is there for him. He's invested” |

Investing in each other's health and adherence: “The objective is for us to both get treatment and for us both to be happy… If you're my partner, I am invested in your long term health and longevity and vice versa.” |

Dependency: “There may be a level of dependency and codependency there…It may get to a point where maybe [the negative partner] does things for [the positive partner] that he ought to be doing for himself” | Could bring each other down: “Depression could set in in one and the other is affected by it… the one that's not depressed wants to help his lover and get fallen into that same mood with his lover.” |

Comprehensive Dyadic Care

Participants described both comprehensive and holistic HIV care, including treatment for couples that expands beyond a biomedical focus. Participants identified other mental and physical health needs in addition to social needs that should be addressed in HIV care, both for individuals and couples living with HIV, including: a variety of types of counseling (relationship counseling, spiritual counseling, stress management, peer counseling, couples support groups), case management, couples-focused educational materials, and an overall focus on staying healthy (e.g. nutrition, exercise, yoga). Some of these aspects of health could be addressed on an individual level (e.g. spiritual counseling); however, participants identified other aspects of care as specific to dyads, including relationship counseling, stress management, couples support groups, and couples-focused educational materials. Dyadic care that addresses mental health was perceived as especially important because it can strengthen the relationship and allow partners to provide additional levels of support to one another.

There was agreement in all five FGDs that HIV care should be comprehensive; however, responses varied on how this care should be provided. Some participants expressed that it is the doctor's role to provide more than simply HIV treatment:

Let's say you have a physician that is actually a physician, but also can speak to your dietary needs, your social support needs, you're having trouble keeping your lights on. Let's try to get a multi-faceted person… a holistic person (P21, FGD3).

Other participants felt that these components of health are beyond the scope of what an HIV doctor should provide, especially with regards to relationship counseling: “This has nothing to do with your doctor's visit. This isn't Dr. Phil. I'm not here to referee your personal love life” (P29, FGD4). Even though some participants felt it was not the doctor's role to provide this additional support, participants commonly agreed that someone should provide additional support, such as a case manager, social worker, or mental health specialist. Participants described HIV care as a “spectrum of care,” which can be appropriately provided through a “care network” or a “one-stop shop.” Both options focus on the interconnectedness of services; however, the “one-stop shop” suggests that services be provided in one, easy to access location:

Especially since we talk about…phases of the process… do everything that they can to make sure there's a continuity…that just because the doctor's visit is over doesn't mean that the nurse can't pick up right after that and the social community can't pick up right after that, and the pharmacist picks up right after that; that it is a spectrum of care, not just discrete little chunks that you have to get over and get to every time. (Participant, FGD1).

I think maybe just making sure…there's some connection between groups and support groups and doctors that are actually providing treatment, making sure that everyone knows who to go to for what, the care network of are you feeling down and you need to talk to someone else that's not just a lab coat? (P25, FGD4).

There was agreement on the value of incorporating counseling into dyadic care; however, many participants also addressed the need for individual attention in receiving HIV care. Participants specifically identified the importance of individual care because it ensures confidentiality with the provider, allows for sufficient time to address individual health needs, and provides the opportunity to address personal emotional needs prior to discussing them with one's partner: “I would probably need to get my ducks in a row so that I could reassure my partner what's going to happen going forward” (P5, FGD1). This was consistent for scenarios with both serodiscordant and seroconcordant positive couples; however, the need for individual attention was described differently depending on the dyadic serostatus.

Dyadic Care for HIV Serodiscordant Couples

In dyadic HIV care for serodiscordant couples, some participants described care where the negative partner would attend appointments solely to support his partner, while others identified unique needs specific to the HIV-negative partner that are important to address in a medical or professional setting. These needs included: concerns regarding their own exposure to HIV, staying negative, concerns about their partner's health, the longevity of the relationship, and whether they want to stay committed in the relationship. This is different from the needs of the HIV-positive partner, whose priority is to address living with HIV and receiving HIV care. These different needs can create challenges in obtaining a support system within the partnership:

So, [one partner] being negative needs… to make sure [he] stays negative, making sure that if this relationship is right for [him] that [he] want to stay in that relationship. I think those are huge support items. And then [the positive partner] though doesn't have somebody that can relate firsthand. So, he's going through the fear and the emotion and everything and his partner doesn't necessarily understand that. So I think, from his perspective, he needs that kind of intimate support with what he's going through, that [the negative partner], he just can't, I don't think, provide just because he's not in the same position (P13, FGD3).

While some participants felt that this lack of empathy and understanding would make it impossible for a partner to provide support; other participants saw this as a challenge that could be addressed through dyadic HIV care. Across all FGDs, relationship counseling and stress management were perceived as more necessary in serodiscordant relationships than in seroconcordant positive ones in order to increase empathy and prevent HIV transmission. Participants suggested that individual counseling, dyadic relationship counseling, and community-based organizations (CBOs) can help address these emotional and educational needs:

I need to know what is safe and what's not. I think I need to have more education…I think I would be looking for [CBOs in Atlanta], a professional that can actually tell me what is safe, what is not, what treatments are there. I'd be reaching out to professional associations that could give me information…So that the negative partner does not become positive (P5, FGD1).

I would want some sort of sex plan and maybe also meet with a counselor [together]…It would depend on the sexual rules of each partner and how that would impact the sex life. And then maybe some education and guidance through that… But I also would want [the negative partner] to seek his own individual counseling on the issue (P7, FGD2).

Additional components of HIV care can also provide an additional purpose for the HIV-negative partner to be present for his partner's HIV care:

I also think that structure… providing [the negative partner] with something that he should be doing every three to six months as well, or adding some sort of component…separately from [the positive partner], sort of engage him with the process individually as well (P8, FGD2).

This concept was discussed across all FGDs and both scenarios; however, it was perceived as especially important in serodiscordant relationships because it allows for the space to focus on the needs of the HIV-negative partner as well.

Dyadic Care for HIV Seroconcordant Positive Couples

Participants described dyadic care for seroconcordant positive couples as two separate scheduled appointments, one for each partner with both partners present at these appointments. These appointments would preferably be scheduled consecutively, with the same doctor, at the same facility; however, scheduling challenges and differences in insurance and ability to pay for care may not allow for that.

In this scenario, even though both partners are HIV-positive, their needs will still vary. Partners can differ based on the stage of the HIV infection, reaction to medications, and mental health status. Some participants felt that these dyadic differences would not allow for dyadic care to be successful for seroconcordant positive couples because it would not provide enough individual attention:

I would rather go by myself, period…When you go to see your doctor, you need that attention just for yourself and how can you get that attention that you need if it's two of y'all in the room? And you're not going to be able to get that quality time that you need to understand things for you because y'all bodies are different. So, y'all might be on different retros and that's a whole lot of explaining there, which gets you confused to… what he done saying to you. Then you want to know why he on this and why I'm on that (P27, FGD4).

Other participants recommended that dyadic differences be addressed by incorporating individual time with the doctor into dyadic care.

Even if both participants receive the necessary individual attention from the doctor, an additional challenge is that differences in experiences with HIV may result in “resentment” or poor “morale”:

P15: There may be some sort of feelings or resentment in the event that one partner is doing better in terms of his health care…just faring better in terms of his health and then another partner is not doing well in terms of his health. There may be a sense of resentment on one of the party's behalves. So that could be a challenge.

P20: Absolutely. Well even if you don't resent your partner, then I think just the morale… for you to see that your partner's responding and you're not. So even if you don't resent …you may just start feeling badly about yourself (FGD3).

The “resentment” and “discouragement” that results from different reactions to HIV treatment and stages of HIV infection could also negatively impact the dynamics of the relationship:

On this particular subject, I can speak from experience because on my regimen, I didn't have any side effects. So, I was comfortable. It was like taking a multivitamin. I was fine from there. However, my partner, he had very negative reactions to the medication and so stopped taking the medications. And of course, that created a lot of tension in the relationship. So, I think that that can definitely create a unique dynamic where one individual is discouraged because of the other individual's response to their medications (P29, FGD4).

Alternatively, participants discussed how differences in responses to medication could help partners remain optimistic. The partner experiencing more negative side effects may see evidence in their partner that it is possible to find a regimen that works better. Participants also stated that one partner could help the other in managing those side effects.

Relationship Dynamics

Participants identified that dyadic care is impacted by the dynamics of a partnership; in order for dyadic care to be successful, the partners must show serious commitment, open communication, and honesty. According to participants, showing commitment in a relationship after becoming aware that one or both partners are HIV-positive is as an act of love: “if you really love the person, you decide to stay” (P13, FGD3).

Participants stated that dishonest relationships would not benefit from dyadic care due to concerns regarding privacy and confidentiality. Honesty is required in order to allow for both partners to be completely candid with the doctor in the other's presence; participants described dyadic care as involving “no secrets” and increased “transparency.” In relationships that lack open communication outside of the doctor's office, participants stated that one partner may “have some questions and things that he might not be comfortable asking if his partner is sitting there” (P24, FGD4).

Commitment was also identified as an important factor when considering privacy. If there are “doubts” and “second thoughts” in the relationship that cannot be expressed, there is an extra level of tension in openly sharing with one's doctor. Participants were also concerned that if partners are not committed to each other, then there may be repercussions if the relationship ends after the couple had already started dyadic care. When discussing privacy concerns, one participant asked, “what if the relationship doesn't make it?” (P23, FGD4). So, if partners share together in an appointment with a doctor and then the relationship ends, one or both partners could feel like their privacy was breeched.

On the other hand, in committed relationships that have open communication, participants described dyadic care as leading to increased honesty with both the partner and the doctor:

I actually went through the process going with a partner to the doctor and I think I was more candid with the doctor because all parties were there. I was able to put things on the table and I think the doctor was challenged at being able to see the sincerity of what was coming out the conversation of three of us being there together because a lot of times we sugarcoat things… but when I had the partner there it was nothing to hide…There is nothing to hide to them and there's nothing to hide to the doctor. So we going to let it all out. Maybe they might want to say something that I didn't even know. My own partner might say something, and that did come out, my partner said, shared something and I was like, oh, you know…And the doctor shared back said ‘yeah, this is blah, blah, blah’ so it kind of brought more to the table when there was both of us being there (P28, FGD4).

If the dynamics between partners are positive, that will enable both partners to build rapport with the doctor, thus improving the relationships and the exchange of information.

Strengthening Partnerships

The connection between comprehensive dyadic HIV care and positive relationship dynamics is reciprocal; while positive relationship dynamics work to improve dyadic care, dyadic care can also improve the dynamics in a relationship and strengthen support systems:

I just personally believe that going together would just make their relationship more stronger. That's just the bottom line…because now they both know that they're not alone in it…I think that personally it would make their relationship so much more stronger. I think there will be longevity (P30, FGD5).

One way that participants explained how dyadic care strengthens partnerships is through the establishment of empathy:

If one partner goes, you establish only sympathy because the other partner doesn't understand what the doctor said. But if both partners go, you established empathy where would the one who is effected be like, oh my gosh, I understand that you can go through this and I understand the trauma you're going to go through so I actually understand rather than like, oh yeah, sorry you feel bad today just because. No. Having that doctor there and speaking to both parties will establish the connection between those two and so that it will help strengthen the bonds of the relationship (P6, FGD1).

Dyadic care creates an understanding between partners and allows them to “work together to reach a goal” (P18, FGD3). Participants agreed that dyadic care allows for collaboration across all relationships; however, the goals vary based on dyadic HIV serostatus. In serodiscordant relationships, both partners work towards a goal of maintaining a healthy relationship, preventing HIV transmission, and ensuring that the HIV-positive partner adheres to care and reduces his viral load. In seroconcordant positive relationships, both partners go through the process of accepting their HIV status together, they incorporate HIV care into their lives together, and if adherence is accomplished and viral loads reduced, the relationship is strengthened because both partners can celebrate together:

It would strengthen the relationship because it would become such a part of their lives that, OK, we're going, today's the appointment; let's meet and go. So…the information they're getting and how things are progressing, it really is going to be integrated into their life. Now there really is going to develop an acceptance of what they're going through. So they would become stronger as a couple hopefully (P35, FGD5).

Achieving “goals” together as a couple allows for couples to “normalize” the experience of HIV care and experience a greater level of acceptance. Furthermore, successes in HIV care “reinforce” and strengthen the relationship, allowing for partners to celebrate achievements together as a couple.

Accountability and Adherence

Receiving care as partners rather than individually was also identified as a way to show “commitment” or “solidarity” to one's partner. Participants described commitment in a relationship as leading to increased accountability; each partner adheres to their HIV treatment not only for themselves, but also for their partner. Participants described how this commitment is established in a serodiscordant relationship: “By [the positive partner] taking his drugs, he is showing the [negative partner] that he is there for him. He's invested” (P3, FGD1). As discussed in the FGDs, adhering to a treatment plan shows “investment” in serodiscordant relationships for two reasons: (1) It shows that the each individual cares about his partner's health, working to ensure that he stays negative by reducing his own viral load and (2) It shows an investment in the “longevity” of the relationship because he is trying to keep himself healthy and will therefore be able to be in the relationship longer:

“I think maybe [the negative partner] would possibly need support…I know it would be self-centered in that situation but he may be fearful of losing this person, physically, from this world and…not in a commitment relationship wise but dying …but [the positive partner] maybe supporting [the negative partner] and reassuring him that he's going to do whatever he can and he's going to be OK, too” (P4, FGD1).

This concept of commitment was described similarly when both partners adhere to their treatment in a seroconcordant positive relationship:

The objective is for us to both get treatment and for us both to be happy…live healthy lives…If you're my partner, I am invested in your long term health and longevity and vice versa. I would hope that that same sentiment is reciprocated (P29, FGD4).

In both serodiscordant and seroconcordant positive relationships, adhering to HIV treatment is an act of commitment that represents an investment in not only one's own health, but also the health of one's partner and the longevity of the relationship.

This increased sense of commitment can lead to greater accountability and adherence to an HIV treatment plan:

I think it shows their commitment to each other, serious commitment to each other…If they do those things together, they're obviously in it together, both of them for the long haul and I think it's very positive for them. And in [the positive partner]'s general outlook on himself, he's going to feel better, he's going to work harder to try and stay healthy (P12, FGD2).

While most participants described dyadic care as improving adherence because it allows for both partners to motivate each other, support each other, and hold each other accountable, some participants also identified challenges in adherence due to dyadic care. One challenge to seroconcordant positive relationships is that dyadic differences may cause a lack of motivation; when one partner is feeling unmotivated, he can bring the other one down with him:

I will say that the person's different level because the other person probably has more extreme state of mind, like my partner wanted to go ahead and die… he didn't want to go ahead and live. So you need that extra support then to push the person through… Definitely there was a mental state when they find out one wants to do this, one wants to do that. So medication adherence is kind of hard to get the other person to do when he wants to go ahead and die (P13, FGD3).

Another challenge could be that one of them or both them could start to regress and not want to go to their appointments…depression could set in in one and the other is affected by it and because… the one that's not depressed wants to helps his lover and get fallen into that same mood with his lover. They just say F it (P31, FGD5).

Another challenging concept or “red flag” discussed by the participants involved dependence on one's partner. This was discussed in terms of personal responsibility versus relationship accountability. Participants explained that no matter the accountability within the relationship, the ultimate importance is one's personal accountability in adhering to their HIV treatment:

There may be a level of dependency and codependency there…It may get to a point where maybe [the negative partner] does things for [the positive partner] that he ought to be doing for himself (P9, FGD2)

Though relationship accountability was perceived as an important factor in increasing adherence, it functions best when it serves the purpose of increasing one's personal accountability rather than replacing it. Ultimately, an individual may feel a stronger personal accountability in adhering to treatment because they are in a committed relationship, but that desire to adhere needs to come from within and not only from the partner.

Participants discussed how dyadic care and relationship dynamics can impact accountability and adherence across the continuum of care, including specific examples for linkage to care (e.g. having a partner present at that first doctor's appointment shows commitment), engagement in ongoing care (e.g. attending visits with a partner can increase appointment attendance), and HAART adherence (e.g. partners can monitor and support each other's health behaviors and adherence to increase accountability, committing to a medication regimen is a sign of commitment).

Discussion

Results point to a mutual relationship between positive relationship dynamics and dyadic HIV care among same-sex male partnerships, which can lead to an increased sense of “solidarity,” allowing both partners to “work together to reach a goal.” Data from the FGDs suggest that relationship dynamics are an important factor on HAART adherence; these data expand upon previous research13,19-21,23,24 by examining how dyadic HIV treatment may increase accountability through an increased sense of “togetherness.” When GBM adhere to care, they are actively showing commitment to their partners; this sense of commitment also holds GBM accountable to adherence. These findings show that it may be useful to promote commitment and positive relationship dynamics as a measure for improving HIV care; messaging around HIV care for MSM may benefit if it shifts to a dyadic focus that addresses same-sex male couples.

These symbiotic and complex relationships were discussed as a source of increased retention throughout the continuum of care. These findings are especially valuable in the context of a shift for HIV interventions to a test-and-treat framework that focuses on the continuum of care.5 An executive order released by President Obama in July 2013, created the HIV Care Continuum Initiative, which calls for HIV strategies to prioritize the continuum of care in order to focus on prevention and treatment simultaneously and to address gaps in receiving optimal treatment.39 Within this context, it is important to understand how dyadic strategies could potentially improve services at each stage in the continuum of care. Findings from this study suggest that there may be many benefits to a dyadic focus for linkage to care, engagement in care, and HAART adherence; the possibility for comprehensive dyadic care to strengthen relationships and increase accountability and adherence can work to increase motivations for care at each stage across the continuum.

There were some limitations in this study. These data are not generalizable beyond this specific cohort; however, these data are able to explain complexities in the relationship between same-sex male partner dynamics and dyadic HIV care. Since FGDs were meant to capture general perceptions of dyadic care, FGDs used scenarios in order to allow GBM in same-sex relationships to discuss dyadic care, despite dyadic serostatus. We did not collect data on HIV status, therefore data cannot be stratified by individual or dyadic serostatus; however, participants had a wide range of knowledge of how HIV care works and discussed a wide range of experiences in the FGDs, whether based on personal experience with HIV or experience from others in their community. The moderator clearly explained the continuum of care, including descriptions and questions at each step, in order to ensure that all participants understood how care is generally provided.

Despite limitations, these data indicate a need for comprehensive care that focuses on more than just medication and allows space for patients to interact with more than just “a lab coat.” The experience of living with HIV expands beyond reducing a virological load, and when other aspects of health, especially mental health, are incorporated into care, it is easier to focus on a patient's medical needs. Furthermore, a focus on dyadic mental and physical health improves overall health and HIV care for both the individual and couple by increasing support for HAART adherence and focusing on preventing seroconversion in discordant dyads. Participants also recommended that comprehensive treatment occur at a “one-stop shop”; this concept is similar to the patient-centered medical home legislation addressed in the Obama administration's Affordable Care Act (ACA). The medical home model describes an organization of the medical system that includes “coordinated, comprehensive, efficient, and personalized” care.39 A “one-stop shop” or medical home model for HIV treatment would establish one location where patients have a primary provider, but also where care is coordinated across practitioners, including ID doctors, mental health specialists, nutritionists, etc.

For medical homes to provide dyadic care they need to be accessible to couples; this includes the capacity to schedule appointments for couples and increased awareness about the availability of dyadic care. Dyadic care should also focus on improving communication between partners; participants in multiple FGDs suggested having both partners “make a plan” prior to attending each appointment. This “plan” should incorporate a discussion of each partner's informational needs, including any questions or concerns that they have for the provider. Tools, such as paper forms or electronic applications, that allow partners to identify talking points and needs for HIV care appointments could ensure open communication between both partners as well as with the care provider.

Despite decades of programmatic focus and intervention, MSM continue to be the only risk group in the U.S. in which HIV incidence is increasing. Evidence indicating high rates of HIV transmission within main partnerships demonstrates the need to create novel dyadic interventions for MSM. Dyadic HIV care that is comprehensive, focuses on both individual and dyadic needs, and promotes positive relationship dynamics among same-sex male couples could improve HIV treatment across the continuum of care.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by supplemental funds to the grant 5P30AI087714 for the Enhanced Comprehensive HIV Prevention Planning Initiative (CFAR ECHPP Initiative) and the Center for AIDS Research at Emory University (P30 AI050409). Whitney Williams at Emory University also assisted with this research.

Source of Funding: This research was supported by supplemental funds to the grant 5P30AI087714 (DC Developmental Center for AIDS Research) for the Enhanced Comprehensive HIV Prevention Planning Initiative (CFAR ECHPP Initiative). Additional support was provided by the Center for AIDS Research at Emory University (P30 AI050409).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Tamar Goldenberg, Email: tsgolde@emory.edu.

Donato Clarke, Email: dcclarke@dhr.state.ga.us.

Rob Stephenson, Email: rbsteph@emory.edu.

References

- 1.Goodreau SM, Carnegie NB, Vittinghoff E, et al. What drives the US and Peruvian HIV epidemics in men who have sex with men (MSM)? PloS one. 2012;7(11):e50522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan PS, Salazar L, Buchbinder S, Sanchez TH. Estimating the proportion of HIV transmissions from main sex partners among men who have sex with men in five US cities. AIDS. 2009;23(9):1153. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832baa34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartlett JA. Addressing the challenges of adherence. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2002;29:S2. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200202011-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen SM, Van Handel MM, Branson BM, et al. Vital signs: HIV prevention through care and treatment -- United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2011;60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clinical infectious diseases. 2011;52(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng SH, Yang CH, Hsueh YM. Highly active antiretroviral therapy is associated with decreased incidence of sexually transmitted diseases in a Taiwanese HIV-positive population. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2013 doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deeks SG, Phillips AN. Clinical Review: HIV infection, antiretroviral treatment, ageing, and non-AIDS related morbidity. Bmj. 2009;338 doi: 10.1136/bmj.a3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hogg RS, Heath KV, Yip B, et al. Improved survival among HIV-infected individuals following initiation of antiretroviral therapy. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279(6):450. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.6.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG, et al. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(18):1815–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mocroft A, Ledergerber B, Katlama C, et al. Decline in the AIDS and death rates in the EuroSIDA study: an observational study. The Lancet. 2003;362(9377):22–29. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palella FJ, Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338(13):853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brion JM, Menke EM. Perspectives regarding adherence to prescribed treatment in highly adherent HIV-infected gay men. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2008;19(3):181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.11.006. 5// [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darbes LA, Chakravarty D, Beougher SC, Neilands TB, Hoff CC. Partner-provided social support influences choice of risk reduction strategies in gay male couples. AIDS and Behavior. 2012:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9868-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simoni JM, Frick PA, Huang B. A longitudinal evaluation of a social support model of medication adherence among HIV-positive men and women on antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychology. 2006;25(1):74. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stumbo S, Wrubel J, Johnson MO. A qualitative study of HIV treatment adherence support from friends and family among same sex male couples. Psychology. 2011;2(4):318–322. doi: 10.4236/psych.2011.24050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woodward EN, Pantalone DW. The role of social support and negative affect in medication adherence for HIV-infected men who have sex with men. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2012;23(5):388–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wrubel J, Stumbo S, Johnson MO. Antiretroviral medication support practices among partners of men who have sex with men: A qualitative study. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2008;22(11):851–858. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wrubel J, Stumbo S, Johnson MO. Male same-sex couple dynamics and received social support for HIV medication adherence. Journal of social and personal relationships. 2010;27(4):553–572. doi: 10.1177/0265407510364870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gamarel KE, Starks T, Dilworth S, Neilands T, Taylor J, Johnson M. Personal or Relational? Examining Sexual Health in the Context of HIV Serodiscordant Same-Sex Male Couples. AIDS and Behavior. 2013:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0490-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomez AM, Beougher SC, Chakravarty D, et al. Relationship dynamics as predictors of broken agreements about outside sexual partners: Implications for HIV prevention among gay couples. AIDS and Behavior. 2011:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoff CC, Beougher SC, Chakravarty D, Darbes LA, Neilands TB. Relationship characteristics and motivations behind agreements among gay male couples: Differences by agreement type and couple serostatus. AIDS care. 2010;22(7):827–835. doi: 10.1080/09540120903443384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson M, Dilworth S, Taylor J, Darbes L, Comfort M, Neilands T. Primary relationships, HIV treatment adherence, and virologic control. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(6):1511–1521. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0021-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell JW, Harvey SM, Champeau D, Moskowitz DA, Seal DW. Relationship factors associated with gay male couples' concordance on aspects of their sexual agreements: establishment, type, and adherence. AIDS and Behavior. 2011:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0064-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Bassel N, Remien RH. Family and HIV/AIDS. Springer; 2012. Couple-based HIV prevention and treatment: State of science, gaps, and future directions; pp. 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Dolezal C, et al. Couple-focused support to improve HIV medication adherence: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS. 2005;19(8):807. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000168975.44219.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephenson R, Chard A, Finneran C, Sullivan P. Willness to use couples voluntary cousneling and testing services among men who have sex with men in seven countries. AIDS Care. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.808731. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burton J, Darbes LA, Operario D. Couples-focused behavioral interventions for prevention of HIV: systematic review of the state of evidence. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9471-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu E, El-Bassel N, McVinney LD, et al. Feasibility and promise of a couple-based HIV/STI preventive intervention for methamphetamine-using, black men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(8):1745–1754. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9997-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen S, Meinzen-Derr J, Kautzman M, et al. Sexual behavior of HIV discordant couples after HIV counseling and testing. AIDS. 2003 Mar 28;17(5):733–740. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303280-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen S, Tice J, Van de Perre P, et al. Effect of serotesting with counselling on condom use and seroconversion among HIV discordant couples in Africa. British Medical Journal. 1992;304:1605–1609. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6842.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunkle KL, Stephenson R, Karita E, et al. New heterosexually transmitted HIV infections in married or cohabiting couples in urban Zambia and Rwanda: an analysis of survey and clinical data. The Lancet. 2008;371(9631):2183–2191. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60953-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Painter TM. Voluntary counseling and testing for couples: a high-leverage intervention for HIV/AIDS prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;53(11):1397–1411. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roth DL, Stewart KE, Clay OJ, van der Straten A, Karita E, Allen S. Sexual practices of HIV discordant and concordant couples in Rwanda: effects of testing and counselling programme for men. International Jounral of STD & AIDS. 2001;12:181–188. doi: 10.1258/0956462011916992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan PS, White D, Rosenberg E, et al. Safety and acceptability of couples HIV testing and counseling for US men who have sex with men: a randomized prevention study. Journal of International Association of Providers in AIDS Care. doi: 10.1177/2325957413500534. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stephenson R, Finneran C. The IPV-GBM Scale: A New Scale to Measure Intimate Partner Violence among Gay and Bisexual Men. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e62592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Executive Order: Accelerating improvements in HIV prevention and care in the United States through the HIV Care Continuum Initiative. 2013 http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/07/15/executive-order-hiv-care-continuum-initiative.