Abstract

Context

Little research has focused on symptom management among women with ovarian cancer. WRITE Symptoms (Written Representational Intervention To Ease Symptoms) is an educational intervention delivered through asynchronous web-based message boards between a study participant and a nurse.

Objectives

We evaluated WRITE Symptoms for: 1) feasibility of conducting the study via message boards; 2) system usability; 3) participant satisfaction; and 4) initial efficacy.

Methods

Participants were 65 women (mean age 56.5 [SD=9.23]) with recurrent ovarian cancer randomized using minimization with race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White vs. minority) as the stratification factor. Measures were obtained at baseline and two and six weeks post-intervention. Outcomes were: feasibility of conducting the study, system usability, participant satisfaction, and efficacy (symptom severity, distress, consequences, and controllability).

Results

Fifty-six (87.5%) participants were retained and the mean usability score (range 1–7) was 6.18 (SD=1.29). All satisfaction items were scored at 5 (of 7) or higher. There were significant between-group effects at T2 for symptom distress, with those in the WRITE Symptoms group reporting lower distress than those in the control group [t(88.4)=−2.57; P=0.012], with a similar trend for symptom severity [t(40.4)=−1.95; P=0.058]. Repeated measures analysis also supported a group effect, with those in the WRITE Symptoms group reporting lower symptom distress compared with those in the control condition [F(1, 56.7)=4.59; P=0.037].

Conclusion

Participants found the intervention and assessment system easy to use and had high levels of satisfaction. Initial efficacy was supported by decreases in symptom severity, distress, and consequences.

Keywords: Ovarian neoplasm, health communication, telenursing, palliative care, randomized trial, patient education, symptom management

Introduction

Despite high disease response rates to front-line therapy, most women with ovarian cancer experience disease recurrence [1–6]. They face re-initiation of chemotherapy multiple times throughout the rest of their lives and they experience, on average, four episodes of recurrence/disease progression, each followed by a new chemotherapeutic regimen [7]. These patients experience a wide range of cancer- and treatment-related symptoms that tend to increase in severity over time [8–11], including an average of 12 concurrent symptoms that influence their quality of life (QOL) [11–13]. Despite the significant influence that these symptoms have on QOL, discussions of symptom management often have a low priority in clinical settings [7,14]. This paper reports initial testing of a web-based interactive educational intervention – WRITE Symptoms (Written Representational Intervention to Ease Symptoms) – for women with recurrent ovarian cancer [15,16].

Over the past 25 years, significant progress has been made in cancer symptom management with interventions for single symptoms or combinations of investigator-selected symptoms such as pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and/or depression [17–24]. Investigators have achieved moderate success with tailored interventions to improve multiple patient-selected symptoms [25–29]. In general, most of these interventions require either intensive face-to-face or telephone contact between the patient and interventionist, or depend on technologies to deliver the intervention.

Interactive computerized patient education programs have been shown to be feasible and acceptable to a wide variety of clinical populations, ages, and ethnicities, and using a variety of technologies [30–34]. In a recent review of computer-mediated patient education interventions, the use of theoretically guided components such as problem solving have been shown to be critical for improving outcomes, but in chronic diseases with complex disease management demands (such as cancer), expert medical advice or coaching was required in addition to the problem solving [32]. Few of these interventions focused on cancer symptom management and only one very recent study connected nurses and patients over asynchronous web-based message boards in order to provide a convenient symptom management intervention [35].

WRITE Symptoms was developed to build on the most successful aspects of previous multi-symptom interventions and to overcome their limitations. It is based on the Representational Approach (RA) to Patient Education (described in detail elsewhere [15,16]). Table 1 provides the key elements of the intervention. The RA is an intervention theory that emphasizes the critical importance of patients’ illness representations – what patients know and understand about their health problems [36–38]. Representational interventions have been effective in face-to-face and/or telephone interactions for cancer pain management [17,18], end-of-life decision making [38,39], and symptom management for elderly breast cancer survivors [28]. WRITE Symptoms is the first implementation of the RA using a web-based, asynchronous delivery mode.

Table 1.

Overview of the Representational Approach and Its Application to WRITE Symptoms

| Element | Goals of Each Element |

|---|---|

| 1. Representational Assessment | Patient is encouraged to describe her symptoms based on the five dimensions of representations: identity, cause, timeline, consequences, and cure/control. The goal is to get a clear picture of the patient’s understanding of her problem and to identify any areas of concern (including gaps, misconceptions, and/or confusions). |

| 2. Identifying and Exploring Gaps, Errors, and Confusions | Patient is encouraged to talk about her concerns regarding symptoms and symptom management. The goal is to understand the patient’s concerns, how they developed and what effect those concerns have on her current management strategies. |

| 3. Creating Conditions for Conceptual Change | The goal is to help the patient recognize the limitations of her current conceptions (ways in which concerns, gaps or confusions may be interfering with optimal symptom management) and to promote a belief that good symptom management is important and attainable with ongoing effort. Conceptual change often occurs spontaneously as the patient has the opportunity to reflect on her experiences. When this does not occur spontaneously, it can be facilitated by making direct links between current representations, coping strategies, and any consequences that the patient has identified. |

| 4. Introducing Replacement Information | Present credible information regarding symptom management to fill in gaps in knowledge, address concerns, clarify confusions, and replace current misconceptions. This information is based on a library of symptom management algorithms and self-care guides. |

| 5. Summary | Discuss expected benefits associated with using new strategies. Emphasize the potential for reducing current consequences reported by patient. |

| 6. Goal Setting and Planning | Work with patient to develop goals related to improving symptom management and specific strategies for reaching those goals. |

| 7. Follow-Up Contact: Goal & Strategy Review | Discuss whether patient was able to implement strategies, what problems were encountered, any concerns patient has, how well strategies worked, and whether goal was reached. |

| Discuss continuing with same strategies or making modifications. | |

| Encourage patient to continue same pattern of implementing, evaluating, and modifying strategies to manage health problems. |

WRITE Symptoms is delivered through private web-based message board interactions between a study participant and a nurse, providing participants with a single “place” to go to work on symptom management at times that are convenient, a feature that has shown benefit in computer-mediated health interventions [33,34,41]. Finally, asynchronous messaging provides the nurse with time to review the participant’s concerns, gather information, and prepare an individualized response in an organized, timely fashion (within 24 hours of each participant posting). Similarly, participants have time to process new information, review and reflect on previous postings, and generate their own strategies for symptom management – a process hypothesized to be critical for promoting conceptual and behavioral change.

The purpose of this pilot study was to evaluate WRITE Symptoms delivered via web-based message boards, specifically 1) the feasibility of conducting the study; 2) the usability of the web-based system; 3) participant satisfaction; and 4) the effect of WRITE Symptoms compared with usual care on symptom representations (symptom severity, distress, consequences, and controllability).

Methods

Design

Participants were randomized with equal allocation (1:1) to WRITE Symptoms versus wait-list control. Random assignments were generated using minimization, an adaptive stratified randomization approach, with race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White vs. minority) as the stratification factor. Using this dynamic allocation method, possible treatment group imbalance was minimized between non-Hispanic White and minority race/ethnicity groups. Measures were obtained at baseline and five and nine weeks (two and six weeks post-intervention).

Sample

Inclusion criteria were: recurrent or persistent ovarian cancer (disease persisted or recurred after primary therapy); three or more concurrent symptoms related to cancer or its treatment; ability to read and write in English; consistent access (defined as any kind of access through home or work) to the Internet and e-mail; and state of residence. State of residence was important because given the nursing assessment and intervention skills used in the intervention, interventionists had to have licensure for states in which participants resided. We enrolled women from 25 states – 19 through the nurse licensure compact (https://www.ncsbn.org/nlc.htm) and six through individual state licenses.

Women were recruited through: 1) advertisements on ovarian cancer advocacy websites and newsletters, and 2) letters from the National Ovarian Cancer Coalition division presidents to 475 members. Those interested in participating contacted research personnel via e-mail, toll-free telephone number, or return interest form (for those receiving a letter).

Once eligibility was confirmed, a consent form was mailed (via standard mail or e-mail, based on participant preference). The project director called each potential participant to review the consent form, answer questions and obtain oral consent. Participants returned the signed consent form in a pre-paid return envelope.

Data Collection Procedures

After consenting, participants were provided with a user ID, password, and an orientation booklet to guide them through study procedures. They were instructed to log-in to the website (www.writesymptoms.com). The home page directed them to a link to complete online initial assessment forms (baseline measures). E-mail reminders were sent at 7, 10, and 14 days following the initial e-mail to those who had not completed the baseline measures. Following completion of the baseline measures, participants were randomly assigned to condition via a web-based randomization program.

Participants were informed via e-mail of their group assignment. Those randomized to WRITE Symptoms were instructed to access their private message board on the website where the research nurse’s first message had been posted. Those randomized to the control condition were informed about the timeline of their participation and were told that after completing the third set of assessment measures, they could opt to receive the WRITE Symptoms intervention. A detailed retention protocol of reminders (e-mail and phone), and thank you notes (e-mail and postal) was assiduously followed for all participants.

Experimental Procedures

WRITE Symptoms

WRITE Symptoms has seven elements, as summarized in Table 1. Participants completed the Symptom Representation Questionnaire (SRQ) to identify their three target symptoms. These three symptoms were the focus of the intervention. The symptom management information was drawn from an evidence-based message library of self-care guides but was individualized by the nurse to each participant’s experiences and representations. Self-care guides for each symptom were mailed or e-mailed (based on participant preference) to reinforce the education provided by the research nurse. The guides were based on the format used by Yarbro and colleagues [42], providing a description of the symptom, strategies to prevent and/or manage the symptom, and a summary of important information to communicate with health care providers. Symptom management recommendations in the guide include two broad categories: symptom management that requires intervention by a health care provider (e.g., medication, procedures, referrals) and self-management strategies [42]. The guides were updated through a review of the literature, and critically reviewed by three gynecologic oncologists and two advance practice oncology nurses. Through the course of the intervention, the nurse and participant worked together to generate care plans for each symptom that included highly individualized symptom management goals and several very specific strategies to reach the goals. The final care plan contained a description of symptoms, the effect of symptoms on function and QOL, current strategies, goals for improving management, and the new strategies that the participant wanted to try. Participants were encouraged to print the care plan and share it with their health care providers.

Both nurse interventionists were Master’s prepared, with a background in oncology nursing. They took part in an intensive two-day workshop in ovarian cancer symptom management and the RA followed by ongoing training that included updating the symptom care guides, reading in the theoretical underpinnings, and four weeks of mock intervention training, which included extensive performance feedback. During the WRITE Symptoms intervention, research nurses did not give information outside the scope of practice, and referred each participant to her own health care provider for specific prescriptive information. The nurses had no contact with patients outside of the message board.

Wait-List Control Group

Participants in the control group completed measures on the website at baseline and five and nine weeks later. After the nine-week measures were completed, participants in the control group were offered the WRITE Symptoms intervention.

Measures

Feasibility of conducting the study and delivering WRITE Symptoms via web-based message boards was assessed by descriptive statistics examining: 1) participant retention, and 2) time and number of postings from the date of the first to the date of the last message (length of time).

Usability of the WRITE Symptoms website and message boards was assessed using the Post-Study System Usability Questionnaire (PSSUQ) [43], which contains 20 items addressing system attributes known to influence users’ perception of system usability. The items are rated on a seven-point scale anchored with 1 (strongly agree) and 7 (strongly disagree) and a “not applicable” (N/A) option outside the scale. The reliability of the overall score has been reported as 0.97 [43]; α=0.96 in the current study.

Satisfaction with the WRITE Symptoms intervention was assessed at six weeks post-intervention with the WRITE Symptoms Satisfaction Survey (WSSS), which comprises 11 items about the importance of WRITE Symptoms, the acceptability of using writing as the primary mode of communication, and the perceived improvement in symptom management. Response options range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Reliability was α=0.89 in the current study.

Symptom Outcomes were assessed with four subscales of the SQR [11]: severity, distress, consequences, and controllability. In previous work with 713 women with ovarian cancer, the subscales demonstrated excellent internal consistency reliability (α > 0.80 for all subscales) and construct validity [11].

Symptom severity was assessed with the first part of the SRQ, a list of 25 symptoms associated with ovarian cancer and/or its treatment. Participants rated the severity of each symptom at its worst in the past week with response options from 0 (did not have) to 10 (as bad as I can imagine). They then selected the three symptoms they “noticed most” in the past week. These were their “target symptoms.” The severity score was the mean of the three target symptoms. Test-retest reliability over a three-day period was 0.82 [11]. Participants then completed the rest of the SRQ for each of their three target symptoms. The response options for the remaining subscales are on five-point scales of 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Mean subscale scores were calculated from the items in each subscale across all three target symptoms. In a previous study, the validity of creating mean scores across different symptoms was supported based on consistent dimensionality and strong internal consistency (0.71–0.92) and test-retest reliability (0.66–0.82) when using items from each of the three most noticed symptoms [11].

Symptom-related distress was operationalized with three items for each target symptom addressing the extent to which each symptom is intrusive, worrisome, and distressful. Alpha reliability for this scale ranges from 0.78 to 0.88; test-retest reliability was 0.78. Alpha was 0.89 in the current study.

Consequences of symptoms were assessed with five items for each target symptom addressing the extent to which the symptom affects the person's life. Reliability for this scale ranges from α = 0.81 to 0.85; test-retest reliability is 0.76. Alpha was 0.86 in the current study.

Controllability of symptoms was assessed with five questions for each target symptom addressing the extent to which the person believes the symptom could be controlled. Alpha reliability for this scale ranges from 0.67 to 0.83; test-retest reliability was 0.66. Alpha was 0.88 in the current study.

Covariates: Sociodemographic characteristics were assessed using the Center for Research in Chronic Disorders Socio-Demographic Survey. Date and type of most recent chemotherapy was assessed at each time point using an investigator-developed Disease and Treatment survey; this information was used to create a single treatment status variable, currently receiving chemotherapy (yes vs. no) to be considered as a potential time-dependent covariate.

Data Analysis

All analyses used SAS v. 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Analyses were conducted to describe the data and identify anomalies that could invalidate the planned analytic procedure. Measures of central tendency and dispersion were computed for continuous variables, and frequency counts and percentages were used for categorical variables. Repeated measures analysis using linear mixed modeling via SAS PROC MIXED was used to investigate the effect of WRITE Symptoms compared with wait-list control on symptom representations (severity, consequences, controllability, and distress) over time. Randomized group assignment was a fixed between-subjects effect, and time and the interaction of group by time were fixed within-subjects effects. Random subject effects were included in the model. Restricted maximum likelihood estimation was used to fit repeated measures models for each outcome and to obtain parameter estimates. The best fitting variance-covariance structure for the repeated measures was identified using standard criteria (i.e., Akaike information criterion, Bayesian information criterion) and was assumed when fitting models. To adjust for possible bias in the estimation of standard errors, the Kenward-Rogers adjustment was applied and Satterthwaite-type degrees of freedom were computed based on this adjustment. The analyses were conducted treating the baseline value of the particular symptom representation subscale score as a covariate in the repeated measures model. Additionally, the fixed covariates of age at entry, educational attainment (less than college degree [< 16 years], college prepared [16 years], more than college [>16 years]), and the time-dependent covariate of whether the participant was currently receiving chemotherapy at the time of the assessment (yes, no) were considered. Examination of the estimated regression coefficients from the fitted models revealed that the baseline value of the outcome variable being modeled and whether the participant was currently receiving chemotherapy at the time of the assessment were the only covariates associated with the outcome; hence, the covariate adjustment in the final models reported were limited to these two covariates. Linear contrasts for the between group comparison at T2 and T3 assessments also are reported.

Results

Feasibility of Conducting the WRITE Symptoms Study

Recruitment

A total of 115 women responded to advertisements, and 156 women (32.8%) responded to the mailed invitations. Of these 271 women, 84 (31.0%) were eligible; 68 (81.0%) eligible women consented. Table 2 provides sample demographic and disease characteristics.

Table 2.

Demographic Information by Group

| Group Mean (SD) or n (%) |

Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Overall (n=65) |

WRITE Symptoms n=33 |

Control n=32 |

Mann- Whitney/ Chi- square |

P-value |

| Age | 56.52 (9.23) | 55.94 (10.37) | 57.12 (2.31) | −1.05 | 0.30 |

| Years of education | 15.95 (2.84) | 15.67 (3.28) | 16.25 (2.32) | −1.40 | 0.16 |

| Marital Status | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Never Married | 5 (7.7) | 4 (12.1) | 1 (3.1) | 4.71 | 0.48 (Fisher’s) |

| Married/partnered | 48 (73.9) | 21 (63.7) | 27 (84.4) | ||

| Widowed | 9 (13.8) | 6 (18.2) | 3 (9.4) | ||

| Divorced/ Separated | 3 (4.6) | 2 (6.0) | 1 (3.1) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | 1.94 | 0.49 (Fisher’s) | |||

| Caucasian | 62 (96.9) | 31 (93.9) | 31 (97.0) | ||

| American Indian | 2 (3.1) | 2 (6.1) | 0 | ||

| Other | 1 (1.6) | 0 | 1 (3.0) | ||

| Education (highest grade attended) | 6.15 | 0.30 (Fisher’s) | |||

| High School | 14 (21.5) | 10 (30.3) | 4 (12.5) | ||

| GED/Vocational/Tech | 5 (7.7) | 3 (9.1) | 2 (6.3) | ||

| 2 or 4 year college | 27 (41.5) | 10 (30.3) | 17 (53.2) | ||

| Graduate school | 19 (29.3) | 10 (30.3) | 9 (28.1) | ||

| Current Employment | 7.25 | 0.26 (Fisher’s) | |||

| Full-time | 18 (27.7) | 7 (21.2) | 11 (34.4) | ||

| Part-time | 13 (20.0) | 9 (27.3) | 4 (12.5) | ||

| Retired | 20 (30.8) | 8 (24.3) | 12 (37.5) | ||

| Full-time homemaker | 11 (16.9) | 6 (18.2) | 5 (15.6) | ||

| Other | 3 (4.6) | 3 (9.1) | 0 | ||

| Religion | 3.12 | 0.40 (Fisher’s) | |||

| Protestant | 22 (33.8) | 13 (39.4) | 9 (28.1) | ||

| Catholic | 16 (24.6) | 7 (21.2) | 9 (28.1) | ||

| No affiliation | 14 (21.5) | 8 (24.2) | 6 (18.8) | ||

| Jewish | 8 (12.3) | 2 (6.10 | 6 (18.8) | ||

| Other | 5 (7.7) | 3 (9.1) | 2 (6.3) | ||

Participant Retention

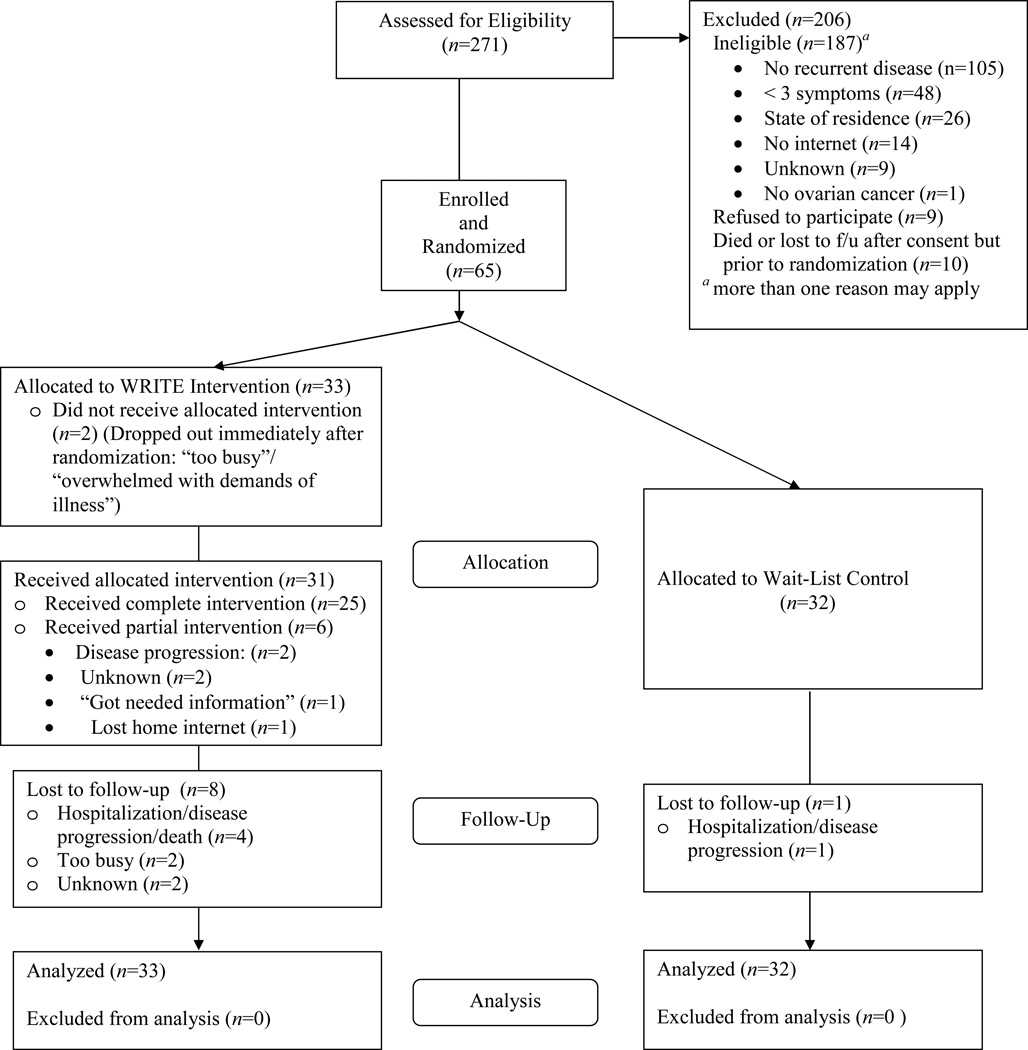

A total of 56 (87.5%) participants were retained on study. Fig. 1 summarizes reasons for ineligibility and participant progress through study.

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram of participant progress through the study.

Of the nine women who were not retained, two withdrew immediately following Time 1 measures, stating they felt overwhelmed with the demands of their illness; five withdrew because of rapid disease progression and/or death; and two were lost to follow-up. The number of subjects who dropped out was higher in the intervention group (n=8) compared with the control group (n=1). Twenty-five participants (75.8%) assigned to WRITE Symptoms completed all elements of the intervention. Of those who did not complete all elements of the intervention, three completed all but Element 7 (goal and strategy review), three did not complete Elements 1–6, and two participants never posted to the message board. No adverse events occurred during the study.

Type and Number of Postings and Time to Complete the Intervention

The most frequently discussed symptoms on the message boards were fatigue (n=13), peripheral neuropathy (n=11), pain (n=7), nausea (n=6) and anxiety (n=6). The mean number of postings for the 33 women randomized to WRITE Symptoms was 15.87 (median = 14; range 0–41). The mean length of participant posts was 260.50 words (median = 210; range 0–808). The mean number of postings to each participant by research nurses was 17.48 (median = 17; range 2–32). The mean length of nurses’ posts was 300.32 words (median = 275; range 1–742). For those completing the intervention, it took the nurse-participant dyads an average of 79 days (median 76; range 37–185) to complete all elements of the intervention. Nurses were required to respond to each participant’s post within 24 hours (Monday through Friday). The average length of time between participants’ posts was 5.77 days (median = 4.5; range 2–16).

Usability of the Study Website and Message Boards

The overall mean score on the PSSUQ was 6.21 (median = 6.73; range 1.10–8.00). Mean scores for the system utility subscales were 6.18 (median = 6.82; range 1.17–8.00); the mean information quality subscale score was 6.20 (median = 7.0; range 1.00–8.00); and interface quality was 6.03 (median = 7.0; range 1.00–8.00). Specifically, women agreed that the website was easy to learn to use (mean = 6.28; median = 7.00; range 1–8); and they were able to complete the questionnaires quickly (mean = 6.17; median = 7.00; range 1–8).

Individual complaints included problems related to being timed-out of the message board, feeling a need to constantly check the website to see if a nurse had posted a message, and taking longer than anticipated to work through all elements of the intervention.

Participant Satisfaction

Data from the 48 participants who completed the WRITE Symptoms Satisfaction Survey (including 23 women from the wait-list control group who ultimately received the intervention) support that patients were very satisfied with the intervention and the web-based message board delivery (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean Scores and Standard Deviations (SD) for Items of the WRITE Symptoms Satisfaction Survey (n=48)

| Item | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| The time I spent writing about symptoms was an important use of my time. | 5.69 | 1.57 |

| The time required to respond to the nurse was worth it. | 5.71 | 1.69 |

| The study was too time-consuming. a | 5.56 | 1.76 |

| I felt comfortable writing about my symptoms. | 6.15 | 1.40 |

| It was difficult to express my ideas in writing. a | 5.08 | 1.98 |

| The level of difficulty of the information presented by the nurse was appropriate. | 5.88 | 1.63 |

| I learned something new from the symptom management program. | 5.73 | 1.66 |

| This symptom management program was useful to me. | 6.00 | 1.41 |

| This symptom management program is important. | 6.47 | 1.20 |

| This program helped me manage my symptoms better. | 5.65 | 1.60 |

| I enjoyed participating in the symptom management program. | 6.35 | 1.47 |

Item reverse scored such that higher scores reflect greater satisfaction.

Preliminary Efficacy

Preliminary analyses presented in Tables 2 and 3 support that the two groups were similar on key sociodemographic, disease and treatment variables. There were significant differences between group effects at T2 for symptom distress, with those in the WRITE Symptoms group reporting lower distress than those in the control group [t(88.4)=−2.57, P=0.012]. There also was a trend for lower symptom severity among the WRITE Symptoms group compared with those in the control group [t(40.4)=−1.95; P=0.058]. In repeated measures analyses, there also was a significant group effect in favor of the WRITE Symptoms group for symptom distress [F(1, 56.7)=4.59; P=0.037]. No between-group effects were seen for symptom consequences or controllability.

Table 3.

Cancer, Treatment, and Symptom Variables at Baseline by Group

| Group Mean (SD) or n (%) |

Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Overall ( n = 65) |

WRITE Symptoms n=33 |

Control n=32 |

Mann-Whitney/ Chi-square |

P-value |

| Months since diagnosis | 51.40 (43.53) | 47.53 (31.94) | 55.40 (53.16) | −0.07 | 0.95 |

| No. of prior surgeries | 1.72 (0.93) | 1.64 (0.78) | 1.81 (1.06) | −0.38 | 0.70 |

| No. of new chemo regimens | 3.67 (2.19) | 3.31 (1.66) | 4.03 (2.60) | −0.99 | 0.32 |

| Stage at diagnosis | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | 4.73 | 0.30 |

| Stage I | 4 ( 6.2%) | 3 (9.1%) | 1 (3.1%) | (Fisher’s) | |

| Stage II | 8 (12.3%) | 2 (6.1%) | 6 (18.8%) | ||

| Stage III | 44 (67.7%) | 23 (69.7%) | 21 (65.6%) | ||

| Stage IV | 7 (10.8%) | 3 (9.1%) | 4 12.5%) | ||

| Don’t know | 2 ( 3.1%) | 2 (6.1%) | 0 | ||

| Prior Radiotherapy: | 2.16 | 0.19 | |||

| Yes | 5 (7.8%) | 1 (3.0%) | 4 (12.9%) | (Fisher’s) | |

| No | 59(92.2%) | 32 (97.0%) | 27 (87.1%) | ||

| Current Ca-125 Level: | 150.62 (323.77) | 124.18 (273.02) | 177.93 (371.83) | −0.14 | 0.89 |

| Current evidence of disease? | |||||

| Yes | 54 (83.1%) | 29 (87.9%) | 25 (78.1%) | 1.10 | 0.29 |

| Currently receiving chemo? | |||||

| Yes | 52 (80.0%) | 28 (84.8%) | 24 (75.0%) | 0.985 | 0.32 |

| Symptom Representations | |||||

| Symptom Severity | 6.05 (2.45) | 5.69 (2.60) | t(63)=0.58 | 0.56 | |

| Symptom Consequences | 2.02 (0.59) | 1.90 (0.73) | t(63)=0.71 | 0.48 | |

| Symptom Controllability | 2.07 (0.62) | 2.12 (0.66) | t(63)=−0.30 | 0.76 | |

| Symptom Distress | 1.91 (0.79) | 1.81 (0.96) | t(63)=0.46 | 0.65 | |

Discussion

Findings support the potential efficacy of WRITE Symptoms for improving symptom-related distress and symptom severity. Counter to expectations, perceived controllability was not increased as a result of the intervention. One possibility is that items in the controllability subscale are not sufficiently sensitive to change. Anecdotally, multiple participants posted during the course of the intervention that writing in response to detailed questions helped them to see their problems more clearly, gave them a sense of control and motivated them to make changes.

Many of the recommended symptom management strategies required health care provider actions. Because the study was conducted outside of clinical settings, it is unclear how many of the suggested strategies were acted on by participants’ local health care providers. Anecdotal evidence from the message boards suggest that not all such interactions resulted in symptom management changes. Future research should collect systematic information on changes in both self-care and medical management strategies following the intervention. In addition, a closer collaboration between the web-based interventionists and the clinicians could enhance the efficacy of the intervention, ensuring that evidence-based recommendations are consistently implemented.

With respect to intervention delivery, it took significantly longer than anticipated for participants to complete the intervention. The realities of disease, treatment, travel, and family demands resulted in women posting, on average, every five days. This stretched the intervention duration to an average of 76 days, over three times as long as expected. Because we had timed follow-up assessments to occur two and six weeks after a subject completed the intervention, there was wide variability in elapsed time between baseline and the follow-up assessments. This programming structure has been modified in current versions of the system so that the intervention period is limited to eight weeks and all participants complete follow-up measures at eight and 12 weeks from baseline regardless of group status or completion of the intervention.

This discrepancy in timing in follow-up assessments is a study limitation. Control group participants all completed follow-up measures at five and nine weeks after baseline; however, intervention subjects completed measures an average of 13 and 17 weeks post baseline. The potential bias introduced from the delay in assessments in the intervention group in this population of women with recurrent ovarian cancer would likely be towards having worsened symptoms over time rather than spontaneous improvement of symptoms. Therefore, the effects seen in these findings are more likely to be under- rather than overestimated.

The study provided important insights about the logistics of delivering a complex symptom management intervention using asynchronous postings on web-based message boards. For example, because all interactions between the nurses and the participants occurred via the message board, problems with the use of the message board had to be addressed without relying on the board itself. Therefore, we made study support staff available by telephone and e-mail and used a printed User Guide to provide detailed instructions about the study website and procedures. These mechanisms were effective in addressing participant confusion.

Participant retention over the duration of the study was excellent and comparable to rates seen in a review of web-based interventions for depression and anxiety [44]. Attrition was higher in the intervention group, likely because of the time and effort required. Attrition is to be expected in women with significant risk of morbidity from advancing disease and intensive treatment regimens.

This study contributes to knowledge on recruitment strategies for web-based interventions. In an attempt to draw participants from across the country, we focused initial recruitment efforts on web-based advertising through ovarian cancer support organizations. Although this approach is financially and time efficient, it has several limitations in that it can lead to sampling bias where participants are those who are already seeking information. Furthermore, successful web-based recruitment requires active advertising about the study by the websites. Such active advertising did not occur for several reasons, including a major website restructuring effort on the part of one of our major support organizations. Because of these problems, we mailed letters to members of the organization to ensure that potential participants learned of the study. Nurse licensure issues also limited recruitment efforts in that we required that a nurse interventionist had to be licensed in the state where a study participant resided.

This study supports the feasibility, acceptability and efficacy of web-based educational interventions [33,34,41]. Future research with WRITE Symptoms should focus on more diverse samples, particularly given evidence that vulnerable populations (minorities, elderly, and those with low incomes) gain the most benefit from computer-mediated patient education programs [30, 31, 35, 45–47]. Other foci for future research include testing the mechanisms by which WRITE Symptoms has an influence on symptom outcomes and determining subgroups of patients for whom the intervention is most effective. Of particular interest is identifying the relative contributions of the specific (theory-guided) factors associated with representational interventions and the non-specific (or common) factors associated with other psycho-educational interventions [48]. A randomized trial (R01 NR010735; GOG-0259) currently underway is recruiting participants from clinics across the country to address these issues.

Table 5.

Outcomes Over Time by Treatment Group Adjusting for Baseline Value of Outcome and Current Chemotherapy

| Symptom Outcomes | Summary Statisticsa | Differences Between Groups | Repeated Measures Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2 Mean (SE) |

T3 Mean (SE) |

T2 Mean (SE) t-value(df) P-value |

T3 Mean (SE) t-value(df) P-value |

F-value (n,df) P-value |

|

| Severity | FGroup(1, 31.1)=1.50 P=0.229 |

||||

| WRITE Symptoms | 4.67 (0.43) | 4.58 (0.58) | −0.94 (0.48) t(40.4)=−1.95 P=0.058 |

−0.31 (0.64) t(47.3)=−0.49 P=0.626 |

FTime(1,50.1)=2.77 P=0.102 FG×T(1, 49.6)=1.72 |

| Control Group | 5.61 (0.22) | 4.80 (0.27) | P=0.196 | ||

| Distress | FGroup(1, 56.7)=4.59 P=0.037 |

||||

| WRITE Symptoms | 1.41 (0.13) | 1.42 (0.13) | −0.45 (0.17) t(88.4)=−2.57 P=0.012 |

−0.186 (0.17) t(87.8)=−1.09 P=0.281 |

FTime(1,55)=1.69 P=0.199 FG×T(1,54.1)=2.18 |

| Control Group | 1.85 (0.11) | 1.61 (0.11) | P=0.146 | ||

| Consequences | FGroup(1,57.4) =0.92 P=0.343 |

||||

| WRITE Symptoms | 1.77 (0.10) | 1.76 (0.10) | −0.164 (0.14) t(87.6)=−1.17 P=0.244 |

−0.180 (0.14) t(87.2)=−1.31 P=0.194 |

FTime(1,55.3)=0.86 P=0.357 FG×T(1,54.4)=0.51 |

| Control Group | 1.94 (0.09) | 1.82 (0.09) | P=0.480 | ||

| Controllability | FGroup(1, 50.8)=0.18 P=0.673 |

||||

| WRITE Symptoms | 2.19 (0.11) | 2.11 (0.10) | 0.120 (0.14) t(87.3)=0.84 P=0.404 |

−0.018 (0.14) t(86.7)=−0.13 P=0.898 |

FTime(1, 49.5)=0.02 P=0.891 FG×T(1,48.6)=0.84 |

| Control Group | 2.17 (0.09) | 2.13(0.09) | P=0.365 | ||

Values in cells are reported as least squares mean (standard error for mean) based on a linear mixed model adjusted for baseline level of outcome and whether on current chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research R21 NR07035 (Donovan). The authors are solely responsible for the study design, data collection, data analysis, writing, and interpretation of the data.

WRITE Symptoms is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA.

The authors are deeply indebted to all of the women who participated in this trial. In addition, we are very grateful to the National Ovarian Cancer Coalition for their assistance in recruiting participants.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The investigators have no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- 1.Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:34–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bukowski RM, Ozols RF, Markman M. The management of recurrent ovarian cancer. Semin Oncol. 2007;34(Suppl 2):S1–S15. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dupont J, Aghajanian C, Andrea G, et al. Topotecan and liposomal doxorubicin in recurrent ovarian cancer: is sequence important? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16(Suppl 1):68–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mannel RS, Brady MF, Kohn EC, et al. A randomized phase III trial of IV carboplatin and paclitaxel × 3 courses followed by observation versus weekly maintenance low-dose paclitaxel in patients with early-stage ovarian carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monk BJ, Han E, Josephs-Cowan CA, Pugmire G, Burger RA. Salvage bevacizumab (rhuMAB VEGF)-based therapy after multiple prior cytotoxic regimens in advanced refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pisano C, Bruni GS, Facchini G, Marchetti C, Pignata S. Treatment of recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2009;5:421–426. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donovan HS, Hartenbach EM, Method MW. Patient-provider communication and perceived control for women experiencing multiple symptoms associated with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.06.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun CC, Bodurka DC, Weaver CB, et al. Rankings and symptom assessments of side effects from chemotherapy: insights from experienced patients with ovarian cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:219–227. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0710-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Gruenigen VE, Huang HQ, Gil KM, et al. Assessment of factors that contribute to decreased quality of life in Gynecologic Oncology Group ovarian cancer trials. Cancer. 2009;115:4857–4864. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Gruenigen VE, Huang HQ, Gil KM, et al. A comparison of quality-of-life domains and clinical factors in ovarian cancer patients: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:839–846. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donovan HS, Ward SE, Sherwood P, Serlin RC. Evaluation of the Symptom Representation Questionnaire (SRQ) for assessing cancer-related symptoms. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:242–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donovan HS, Ward SE. Representations of fatigue in women receiving chemotherapy for gynecologic cancers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:113–116. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.113-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. Symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress in a cancer population. Qual Life Res. 1994:183–189. doi: 10.1007/BF00435383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Donaghy K, et al. Patient-related barriers to fatigue communication: initial validation of the fatigue management barriers questionnaire. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:481–493. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00518-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donovan HS, Ward SE, Song M-K, et al. An update on the representational approach to patient education. J Nurs Scholarship. 2007;39:259–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donovan HS, Ward SE. A representational approach to patient education. J Nurs Scholarship. 2001;33:211–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward SE, Donovan H, Gunnarsdottir S, et al. A randomized trial of a representational intervention to decrease cancer pain (RIDcancerPain) Health Psychol. 2008;27:59–67. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward SE, Serlin RC, Donovan HS, et al. A randomized trial of a representational intervention for cancer pain: does targeting the dyad make a difference? Health Psychol. 2009;28:588–597. doi: 10.1037/a0015216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroenke K, Theobald D, Wu J, et al. Effect of telecare management on pain and depression in patients with cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304:163–171. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barsevick A, Beck SL, Dudley WN, et al. Efficacy of an intervention for fatigue and sleep disturbance during cancer chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:200–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Given B, Given CW, McCorkle R, et al. Pain and fatigue management: results of a nursing randomized clinical trial. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:949–956. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.949-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Der Peet EH, Van Den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ, Patijn J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of an intensive nursing-based pain education program for cancer outpatients suffering from pain. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1089–1099. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0564-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miaskowski C, Dodd M, West C, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of a self-care intervention to improve cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1713–1720. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Espie C, Fleming L, Cassidy J, et al. Randomized controlled clinical effectiveness trial of cognitive behavior therapy compared with treatment as usual for persistent insomnia in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4651–4658. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherwood P, Given BA, Given CW, et al. A cognitive behavioral intervention for symptom management in patients with advanced cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:1190–1198. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.1190-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sikorskii A, Given CW, Given B, et al. Symptom management for cancer patients: a trial comparing two multimodal interventions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kearney N, McCann L, Norrie J, et al. Evaluation of a mobile phone-based, advanced symptom management system (ASyMS©) in the management of chemotherapy-related toxicity. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:437–444. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heidrich SM, Brown RL, Egan JJ, et al. An individualized representational intervention to improve symptom management (IRIS) in older breast cancer survivors: three pilot studies. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36:E133–E143. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.E133-E143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, et al. Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:50–62. doi: 10.3322/caac.20093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krishna S, Balas EA, Spencer DC, Griffin JZ, Boren SA. Clinical trials of interactive computerized patient education: implications for family practice. J Fam Pract. 1997;45:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray E, Burns J, See TS, Lai R, Nazareth I. Interactive health communication applications for people with chronic disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD004274. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004274.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dumrongpakapakorn P, Hopkins K, Sherwood P, Zorn K, Donovan H. Computer-mediated patient education: opportunities and challenges for supporting women with ovarian cancer. Nurs Clin North Am. 2009;44:339–354. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tate DF, Finkelstein EA, Khavjou O, Gustafson A. Cost effectiveness of internet interventions: review and recommendations. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38:40–45. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9131-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wantland DJ, Portillo CJ, Holzemer WL, Slaughter R, McGhee EM. The effectiveness of Web-based vs. non-Web-based interventions: a meta-analysis of behavioral change outcomes. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e40. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.4.e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruland CM, Andersen T, Jeneson A, et al. Effects of an internet support system to assist cancer patients in reducing symptom distress: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36:6–17. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31824d90d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leventhal H, Meyer D, Rachman D. The common sense representation of illness danger. In: Leventhal S, editor. Contributions to medical psychology. vol. II. New York: Pergamon Press; 1980. pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leventhal H, Diefenbach M. The active side of illness cognition. In: Skelton JA, Croyle RT, editors. Mental representation in health and illness. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1991. pp. 247–272. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baumann LJ, Leventhal H. “I can tell when my blood pressure is up, can’t I?”. Health Psychol. 1985;4:203–218. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song M-K, Kirchhoff KT, Douglas J, Ward SE, Hammes B. A randomized, controlled trial to improve advance care planning among patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Med Care. 2005;43:1049–1053. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000178192.10283.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song M-K, Ward SE, Happ MB, et al. Randomized controlled trial of SPIRIT: an effective approach to preparing African American dialysis patients and families for end of life. Res Nurs Health. 2009;32:260–273. doi: 10.1002/nur.20320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leykin Y, Thekdi SM, Shumay DM, et al. Internet interventions for improving psychological well-being in psycho-oncology: review and recommendations. Psychooncology. 2011;32:118–121. doi: 10.1002/pon.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yarbro CH, Frogge MH, Goodman M, editors. Cancer symptom management. 3rd ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett; 2004. p. 765. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewis JR. Psychometric evaluation of the PSSUQ using data from five years of usability studies. Int J Human Comput Interact. 2002;14:463–488. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Farrer L. Adherence in internet interventions for anxiety and depression: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e13. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eng TR, Maxfield A, Patrick K, et al. Access to health information and support: a public highway or a private road? JAMA. 1998;280:1371–1375. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.15.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shea S, Weinstock RS, Starren J, et al. A randomized trial comparing telemedicine case management with usual care in older, ethnically diverse, medically underserved patients with diabetes mellitus. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:40–51. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weinert C, Cudney S, Hill W. Health knowledge acquisition by rural women with chronic health conditions: a tale of two web approaches. Aust J Rural Health. 2008;16:302–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2008.01004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Donovan HS, Kwekkeboom KL, Rosenzweig MQ, Ward SE. Nonspecific effects in psychoeducational intervention research. West J Nurs Res. 2009;31:983–998. doi: 10.1177/0193945909338488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]