Abstract

Ineffective nurse–physician communication in the nursing home setting adversely affects resident care as well as the work environment for both nurses and physicians. Using a repeated measures design, this quality improvement project evaluated the influence of SBAR (Situation; Background of the change; Assessment or appearance; and Request for action) protocol and training on nurse communication with medical providers, as perceived by nurses and physicians, using a pre–post questionnaire. The majority (87.5%) of nurses respondents found the tool useful to organize information and provide cues on what to communicate to medical providers. Limitations expressed by some nurses included the time to complete the tool, and communication barriers not corrected by the SBAR tool. Project findings, including reported physician satisfaction, support the use of SBAR to address both issues of complete documentation and time constraints.

Keywords: Interprofessional communication, Nursing home quality, SBAR

Consumer and regulatory expectations to prevent avoidable injuries have created an imperative to create a culture of safety in nursing homes.1–3 Communication between nurses and medical providers (e.g., physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) that supports effective clinical decision-making is critical to support this mandate.4 There is evidence that ineffective nurse–provider communication in this setting adversely affects resident care, with associated reports of unnecessary psychotropic use5 and avoidable hospitalizations,1,6 for example. Additionally, poor communication causes increased stress and frustration, and diminished workplace relationships for both nurses and physicians.7

Although physicians have cited concerns about nurse competence in the nursing home setting,8 knowledge deficits do not account for all the problems with communication. In general, a combination of individual, group, and organizational factors, including cognitive workload, differing priorities between professional roles, and hierarchical relationships, complicate communication.9,10 Most of the communication between nurses and medical providers in the long-term care setting occurs within the context of brief telephone conversations; many calls occur after hours and on weekends to covering physicians.11,12 As a result, important clinical decisions are made by providers who are relying on information from the nurse on the telephone because the provider is unfamiliar with the resident. The quality of this exchange is influenced by both provider and nurse behaviors.8,12

Tjia and colleagues12 reported several barriers to communication perceived by nurses including: lack of physician openness to communication (rushed and/or not open to nurses’ views), logistic challenges (including noise and lack of privacy), lack of professionalism (rudeness and disrespect), and language barriers (accent and use of jargon), as well as inconsistencies in nurse preparedness. Problems related to timing, clarity, and content of information conveyed,12,13 as well as the nurse’s ability to organize and communicate information14 have been cited as culprits contributing to poor communication. These challenges may be mitigated through the development and implementation of structured communication protocols and training of nursing staff on these methods.9,14,15 Standardizing the structure of critical communications helps the speaker organize thoughts and be prepared with critical information, and helps the receiver to be focused on the important points of the message by eliminating the less important aspects.16–18 One communication protocol increasingly and commonly used in healthcare is the SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation) approach.

Originally developed by the United States Navy as a communication mechanism used on nuclear submarines, SBAR was later adopted by the hospital industry in the 1990s at Kaiser Permanente of California as part of their efforts to foster a culture of patient safety.19 SBAR provides a structured method of communicating information that has the potential not only to improve communication but also to directly impact patient care outcomes. In the rehabilitation setting, the use of an SBAR protocol demonstrated perceived improvements in communication and increased safety reporting by staff.20 Additionally, SBAR use was associated with improvement in the quality of warfarin management in nursing home residents.15

The successful management of the clinically complex resident requires that nursing homes provide adequate staffing, communication-specific staff training, and protocol-driven evidence-based care.2,21 Nurses are in a key role to assess resident changes on a 24-h basis in the nursing home environment. The quality and quantity of nursing assessment data are aspects of a clinical protocol that address changes in a resident’s status. How these data are gathered and conveyed to medical providers can dramatically influence medical decision-making. The SBAR approach may provide a viable method for staff to evaluate clinical changes in nursing home residents on an ongoing basis, and effectively communicate these findings to a medical provider, promoting early identification of symptoms, communication of assessment findings, and appropriate management.22,23 The purpose of this quality improvement intervention was to evaluate the feasibility and utility of implementing an SBAR protocol in a long-term care setting.

1. Method

1.1. Design/setting

This quality improvement project employed a single-site repeated measures design. The project was implemented in a 137-bed skilled nursing home, part of a faith-based continuing care retirement community in suburban Pennsylvania. All staff nurses, both registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs), were eligible and invited to participate in the project. The project was considered exempt by the New York University Committee on Activities Involving Human Subjects (NYUCIHS).

1.2. Recruitment

Recruitment of nurses for the project occurred via an initial flyer posted to announce an educational meeting designed to introduce the purpose and basic outline of the project followed by informational meetings describing project implementation phases, expectations of participants, and project procedure. Forty nurses (21 RNs and 19 LPNs; 70% of the staff nurses) consented to participate in the project. Of the 40 participating nurses, 33 participated in the pre-implementation training and completed a questionnaire; seven were not available due to attrition (n = 4), and failure to submit a completed questionnaire (n = 3).

The medical staff in the facility was comprised of seven physicians and one nurse practitioner (the project leader). Six weeks after the nurses’ SBAR training, the physicians were invited to an informational session hosted by the medical director of the nursing home. The project leader described the study and informed the physicians that they would be asked to provide feedback in the form of an open-ended survey regarding their perceptions of communication from nurses after the 4 month implementation period. All seven physicians agreed to participate.

1.3. Protocol implementation

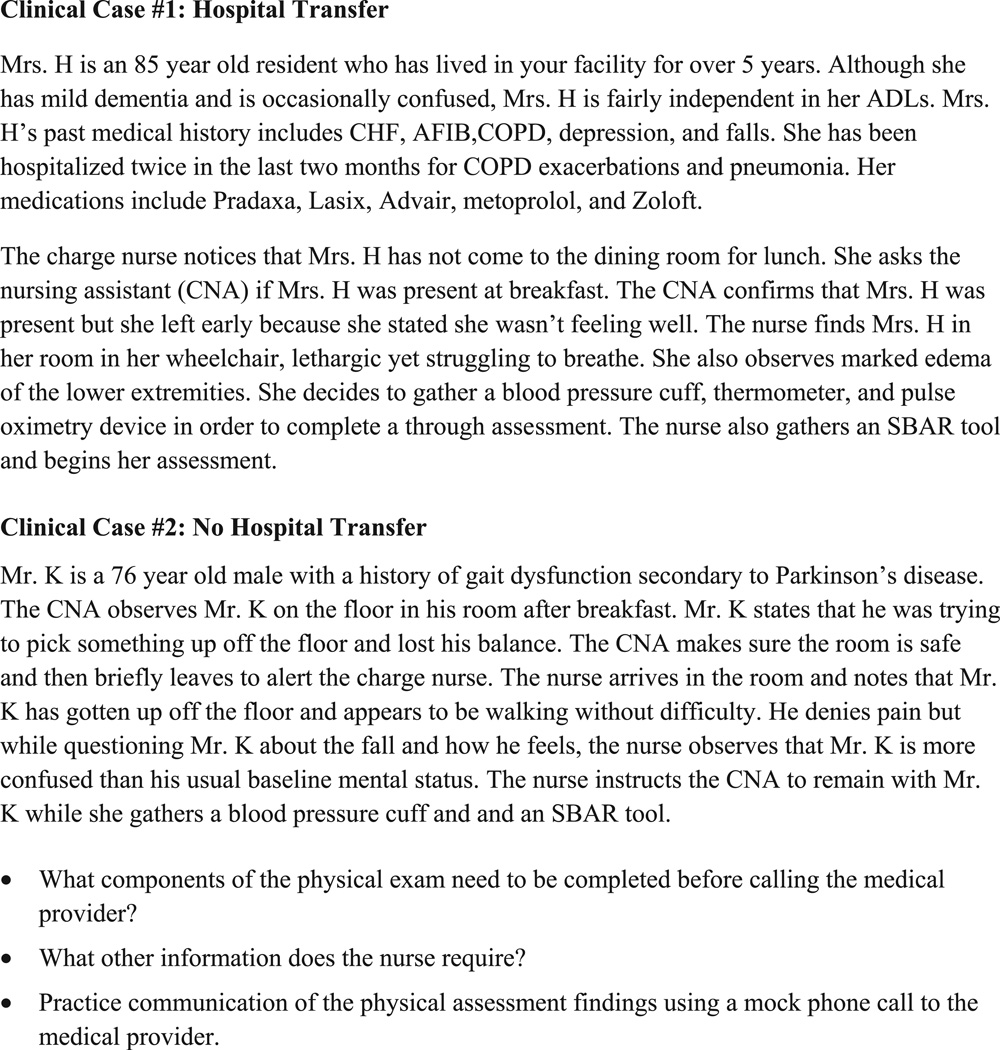

The INTERACT II SBAR Communication Tool and Progress Note developed by Ouslander and colleagues,24 is a clinical and operational tool that was central to the intervention (see web site: http://interact2.net/). The SBAR communication tool provides a systematic approach for nurses to assess and record change in resident status including a description of the Situation (symptoms, onset, duration, aggravating/relieving factors, and other observations); Background of the change (primary diagnosis, pertinent history, vital signs, functional change, mental status change, medications, pain, laboratory studies, allergies, and advance directives); Assessment (conducted by RNs) or description of appearance (provided by LPNs, consistent with scope of practice); and Request for action (suggestion of provider visit, lab work, IV fluids, observation, change in orders, or transfer to hospital). The nurses received training on the purpose and use of the tool, using clinical case scenarios that demonstrated data collection and communication techniques for a change in resident condition (See Fig. 1 for educational scenarios). These 1 h educational sessions were provided on-site at the nursing home by the project leader, an advanced-practice nurse with extensive experience in long-term care.

Fig. 1.

SBAR training scenarios.

The four nursing supervisors received an additional hour of training on strategies to monitor adherence to the protocol. Continued staff support was provided during the course of implementation through weekly visits to the nursing home and/or via telephone conferences.

1.4. Measures

1.4.1. Nurse characteristics

The following information was collected on the professional characteristics of the nurse: education and years of experience: as a nurse, in long-term care, and at the facility.

1.4.2. Outcome measures

The project was evaluated in three ways: 1) nurse satisfaction; 2) medical provider perception of nurse/medical provider communication; and 3) adherence to SBAR implementation.

1.4.2.1. Nurse satisfaction with nurse–medical provider communication

The questionnaire assessed nurse satisfaction with nurse–medical provider communication pre- and post-SBAR implementation, using an adapted version of the Schmidt Nursing Home Quality of Nurse-physician Communication Scale used in Sweden.24 The tool had been modified and validated for use in US nursing homes by Tjia et al with established validity and reliability.12 The questionnaire utilizes a 5-point Likert scale to assess nurses’ perceptions of issues that may affect nurse–physician communication including language barriers, time constraints, respect, nurse training, and logistics of telephone calls. The questionnaire is supplemented with open-ended questions, eliciting information about problematic situations (e.g., “Describe a situation where you had difficulty communicating with a medical provider”), as well as the perceived barriers and facilitators to effective communication with medical providers (e.g., “What prevents/helps effective nurse–medical provider communication?”). We utilized these open-ended questions, developed by Tjia et al12 for the pre-SBAR questionnaire. We supplemented the post-satisfaction questionnaire with open-ended questions that address the usefulness of the SBAR tool, identified limitations, and other comments.

1.4.2.2. Medical provider perception of nurse–medical provider communication

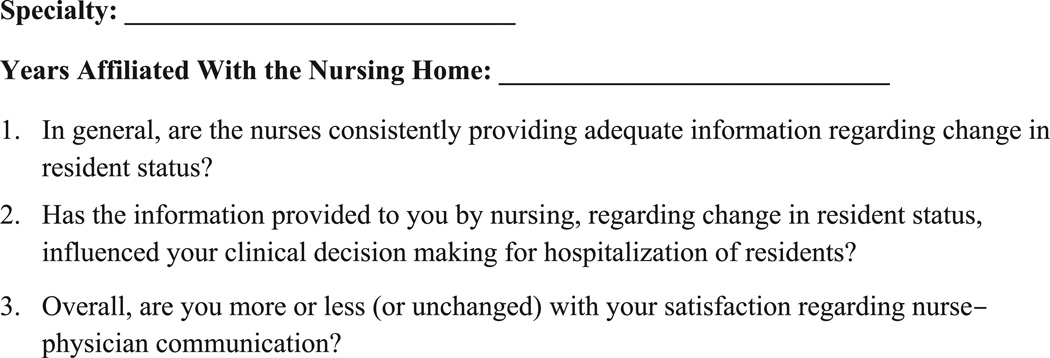

An open-ended questionnaire (Fig. 2) was used to solicit medical provider perception of nurse/medical provider communication post-SBAR intervention. This questionnaire was developed based on a review of the relevant literature and consultation with Jennifer Tjia, MD, an expert in this topic (personal communication, July 17, 2011). The questionnaire was mailed to the seven physicians.

Fig. 2.

Interview with medical providers: perception of nurse/medical provider communication.

1.4.2.3. Adherence to SBAR implementation

The completion of the SBAR communication tool including utilization (reported change in condition), thoroughness (all items completed), and timeliness (completion in its entirety before the end of shift), were recorded. The data were collected by the nursing supervisors through daily audit of the completed SBAR tools for resident change in condition, using the 24 h report as a source for this information.

1.5. Data analysis

Adherence to the SBAR completion was reported as frequency counts. Responses to the pre- and post-satisfaction questionnaires were compared, using group t-tests. Qualitative responses derived from the open-ended questions posed to nurses in the pre-SBAR questionnaire, as well as the physician interviews, were analyzed using standard methods of content analysis.25 Coding was conducted by three project team members (SR, MB, LW). Codes were quantified and grouped into themes based on similarities. For example, a number of codes arose from the data that focused on factors that support effective communication and included nurse confidence and organization of data. These codes were combined under the theme, facilitators to effective communication.

2. Results

As reported in Table 1, LPNs comprised over half (52%; n = 21) of the sample and for the majority of the remaining nurses the associate degree was the highest level of educational preparation. The average experience as a nurse (approximately 5 years) was very similar to total years of experience as a nurse in long-term care.

Table 1.

Nurse participant characteristics.

| Characteristics | Participants (N = 40) |

|---|---|

| N (%) | |

| Licensed Practical Nurse | 21 (52.5) |

| Registered Nurse | |

| Associate degree | 9 (22.5) |

| Diploma | 7 (17.5) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 3 (7.5) |

| Mean (S.D.) | |

| Years experience as a nurse | 5.3 (.96) |

| Years experience in long-term care | 5.0 (1.1) |

| Years experience at this facility | 4.3 (1.2) |

Table 2 reports that thirty-six nurses (90%) reported difficulty communicating with a medical provider. Difficulties communicating with the medical provider are summarized in three main clusters: (1) provider style (e.g., “rude”, “hurried”; n = 31), (2) provider’s treatment decision (e.g., refusing hospice care for a terminally ill resident; n = 3), and (3) provider’s primary language/accent (n = 2).

Table 2.

Nurses’ views on communication with medical provider.

| Communication area | Theme (number of responses) | Examples (direct quotes) |

|---|---|---|

| Difficult situation | Physician Style (31) | The physician was unwilling to allow me to fully explain the situation and my assessment of the patient before giving orders. |

| Doctors intimidating nurses-giving us a hard time or being rude to us. | ||

| MD just started yelling for no reason as if he was being bothered and it was not an emergent situation. | ||

| Physician’s treatment decisions (3) | Resident in end stage of life. | |

| I was following through with initiative of previous nurse for hospice care. Hospice nurse came, contacted on-call doctor re: narcotics; physician denied authorizing hospice. | ||

| Physician language/accent (2) | It was an on-call doctor and he had an accent that was difficult to understand. | |

| No difficulties (2) | ||

| No response (2) | ||

| Barriers to communication | Lack of nurse skill in assessment and data collection (15) | Not calling in a timely manner, unorganized, lacking complete set of facts/assessment. |

| Nurses that don’t have everything ready for when MD calls back. They do appreciate organization. | ||

| Time constraints (6) | It is difficult when they act like they don’t have the time to listen. Busy office hours which can cause extreme wait times on phone (>10 min). | |

| Physician attitude (6) | Mood and disposition of the physician…. | |

| Communication skills-physicians and nurses (4) | Poor listening skills for both. | |

| On-call medical providers (3) | Talking to MDs that do not know the resident. | |

| Noise (3) | He didn’t listen to what was happening with the patient. There was too much background noise. | |

| Can’t often hear well on cell phones. | ||

| No response (3) | ||

| Facilitators to communication | Organization of data (35) | Being through and efficient in the information gathered. |

| Have all your "ducks in a row" before making the call. | ||

| Nurse confidence (2) | Be confident. Don’t be afraid to ask questions or have orders repeated or clarified. | |

| Don’t take comments or attitudes personally. | ||

| No response (3) |

Barriers to effective communication included: (1) lack of nurse skill in assessment and data collection (n = 15), (2) time constraints (n = 6), (3) physician attitude (n = 6), (4) communication skills of physicians and nurses (n = 4), (5) on-call medical providers (n = 3), and (6) environmental noise (n = 3). The facilitators of effective communication included nurse organization of data, nurse confidence in communication, and openness of medical provider to communication conveyed.

2.1. Nurse satisfaction with nurse–medical provider communication

The mean responses of the nurse satisfaction questionnaires, pre- and post-implementation were compared. Table 3 shows that nurse satisfaction, although not statistically significant, demonstrated improvement in the majority of items post-implementation. Post-implementation qualitative comments identified limitations, and other comments. Twenty-eight nurses (87.5%) found the tool useful (“If taken the time to complete prior to MD contact, it organizes and cues nurses on what to communicate and suggest.”), three nurses did not comment, and one nurse did not find it useful. Twenty-two nurses (69%) stated no limitations with the SBAR tool, although nine (28%) found the tool time-consuming. Other comments included: “Use of the tool does not address negative attitude of some physicians” (stated similarly by three nurses), or “environmental problems such as background noise (stated by two nurses).”

Table 3.

Comparison of nurse satisfaction: Pre and post-SBAR implementation.

| Pre-SBAR Mean (SD) N = 40 |

Post-SBAR Mean (SD) N = 32 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. How often do you have difficulty understanding what a physician means due to medical jargon? | 1.8 (1.0) | 1.5 (0.7) | Improved |

| 2. How often does a physician’s language or accent make it hard for you to understand what they are saying? | 2.3 (0.9) | 2.2 (0.9) | Improved |

| 3. How often does a physician have difficulty understanding what you are saying due to your language or accent? | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.7) | Worse |

| 4. How often do physicians interrupt you before you have finished reporting on a patient? | 2.6 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.0) | Improved |

| 5. How often do physicians disregard nurses’ views when making decisions about patients? | 3.0 (0.9) | 2.5 (1.0) | Improved |

| 6. How often are physicians rude to you when you call them about a patient? | 2.4 (0.9) | 2.0 (0.9) | Improved |

| 7. How often do you feel disrespected after an interaction with a physician? | 2.7 (1.0) | 2.7 (1.2) | Unchanged |

| 8. How often do you feel frustrated after an interaction with a physician? | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.2 (0.8) | Improved |

| 9. Difficulty reaching the physician | 3.0 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.8) | Improved |

| 10. Uncertainty about what to tell the physician | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.7) | Improved |

| 11. Feeling that the physician doesn’t want to deal with the problem | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.4 (0.9) | Improved |

| 12. Difficulty finding time to make the call | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.4) | Worse |

| 13. Difficulty finding a quiet place to make the call | 3.0 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.6) | Worse |

| 14. Anticipating that the physician will be rude or unpleasant | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.3 (0.9) | Unchanged |

| 15. Feeling hurried by the physician | 2.7 (1.0) | 2.5 (0.9) | Improved |

| 16. Feeling that I’m bothering the physician | 2.9 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.2) | Improved |

| 17. Worrying that the physician may order something inappropriate or unnecessary | 1.8 (0.9) | 1.8 (0.8) | Unchanged |

| 18. Feeling that I don’t have enough time to say everything that I need to say | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.0 (0.9) | Improved |

| 19. How open is the communication between nurses and physicians in this nursing home? | 3.6 (0.9) | 3.8 (0.9) | Improved |

| 20. How comfortable do you feel communicating with physicians? | 3.6 (0.8) | 4.0 (0.9) | Improved |

| 21. How comfortable do you feel communicating with nurse practitioners? | 4.4 (0.7) | 4.6 (0.6) | Improved |

2.2. Medical provider perception of nurse–medical provider communication

The seven medical providers who provided feedback included a board-certified geriatrician; two physicians board-certified in internal medicine, and four family practitioners. The mean years of affiliation with the nursing home was 7.20 (±5.4; range 2–18). Five physicians reported that the quality of communication with nurses about change in resident condition had improved since project implementation. One physician stated there was no apparent change (had been positive prior to the project implementation); and one stated no change (no improvement with the project implementation). With the exception of the one physician who reported no improvement, the physicians all reported that the nurses were consistently providing adequate information regarding change in resident status and that the information provided by nursing staff influenced the decision-making for hospitalization of residents.

2.3. Adherence to SBAR implementation over the three months

Over the 3 month course of implementation, 65 SBAR tools were completed. A review of the SBAR tools revealed that most (78%; n = 51) had complete documentation, while the remaining 22% (n = 14) had some missing documentation. There was no consistency in sections/areas of non-documentation. The SBAR tools were completed in a timely manner, congruent with the facility’s documentation policy to complete all documentation before the nurse’s end of shift. Only one change of resident condition lacked the completion of an SBAR tool (98% compliance).

3. Discussion

Consistent with other work that demonstrates the effectiveness of SBAR structured communication interventions,15,24 the implementation of the INTERACT II SBAR tool suggests improvement in nurse satisfaction with communication. Similar to Whitson and colleagues,16 the nurses’ baseline satisfaction scores pre-implementation were relatively positive, although nurses qualitatively identified difficult situations to include physician communication style and language/accent. In their initial open-ended responses, many nurses described the importance of skill in data collection and the organization of clinical data, underscoring the need for an SBAR-like methodology.

In addition to the observed positive baseline scores relating to satisfaction with communication, the majority of mean item scores showed increased satisfaction post-SBAR implementation. In particular, areas that appeared particularly problematic in the sample (e.g., physicians interrupting and disregarding nurses’ views, and nurses feeling hurried and bothering the physician) showed improvement. Velji and colleagues20 reported similar improvements from baseline scores suggesting the value of utilizing SBAR methodology. Satisfaction scores did not change in some items including feeling disrespected by a physician, and worrying if the physician may order something inappropriate. This finding suggests the need to augment an SBAR communication protocol with evidence-based interdisciplinary interventions that are institutionally sanctioned to provide consistency in quality. In addition, complementary performance criteria (for both medical providers and nursing staff) may likely reinforce uptake and dissemination.25

The results demonstrate that most physicians expressed satisfaction with communication post-SBAR implementation, improved satisfaction regarding the consistency in data conveyed for change in resident status, and a majority view that the information communicated influences decision-making regarding hospitalization. One potential explanation for these results is the possibility that the utilization of the SBAR protocol improved the quality and concise delivery of information during telephone calls to medical providers, provided by both experienced and non-experienced nurses. Also, the medical providers’ knowledge of the identified barriers to communication and the facility’s initiative to improve communication may likely have improved the medical providers’ receptivity to communication, thereby improving satisfaction. The recent emphasis regarding interdisciplinary education in geriatric literature, medical curricula, and continuing education may have supported the physicians’ openness to efforts to improve communication with nurses.26–28

3.1. Utility of the SBAR

Similar to other studies utilizing SBAR methodology16,20 nurses described its utility. In the post-questionnaire, several nurses replied that the use of the SBAR helped them to “organize their thinking” and “feel more confident in their communication” with the medical providers. Also, respondents reported that they found the tool useful to organize information and cue them on what to communicate to medical providers.

The implementation of the SBAR communication tool coupled with targeted training on the use of the tool has the capacity to improve satisfaction by streamlining and structuring communication. Essentially the tool “takes the guesswork” out of what data should be collected and the method for how it should be reported. Many nurses stated, in their post-questionnaire, that the tool was helpful to streamline data (“get all my ducks in a row”), and assist with “remembering everything that needs to be collected before the phone call.” While many nurses stated that they automatically “go through this process in their heads,” the SBAR tool helped them to reinforce data collection steps and reporting mechanisms. Also, nurses expressed in the training sessions that they were excited about participating in the project and were eager to learn about the existing evidence that supported the project development. Thus the improvement in their overall satisfaction appeared to be related to feeling valued and respected in their capacity as professionals, who were asked to participate in this project. Many expressed that they wanted to “do a good job” and were anxious to learn about methods that could enhance their skills.

The SBAR tool has the potential to diminish the stress of a nurse when communicating information. Clear communication not only has the potential to improve nurse and medical provider satisfaction but also can improve care outcomes and resident safety.12,15 SBAR, an approach to communication that can be applied to any long-term care facility, promotes the efficient delivery of concise information. These factors are of particular importance within this care environment where timing of phone calls is often reported as one of the barriers to successful communication.16 As many nurses stated, SBAR “takes the guesswork out of the equation” and gives the nurse a delivery template that can be utilized by any nurse, regardless of years of experience. Project findings support the use of SBAR in the long-term care setting to address both issues of complete documentation and time constraints.23 As outlined by Whitson et al,16 nurses who utilized an SBAR-type tool felt better prepared to answer questions, were able to deliver content in a more concise manner, and reported improved satisfaction.

3.2. Systemic considerations

The administrative support (including that of the medical director) for the project likely contributed to nurse satisfaction. As one nurse described during the SBAR training, the physician’s awareness of the project, and administration’s support was likely to contribute to the positive improvements in communication. We found that SBAR training utilizing case scenarios, demonstrating SBAR application in practice, may be extremely helpful, especially for new nurses, to improve communication. SBAR training, consistently integrated into nursing curricula, may likely provide a foundation for future practice, consistent with the national initiative Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) that seeks to promote competencies needed by nurses to improve healthcare quality.29

This project has policy implications, related to scope of practice, which require closer analysis. While the SBAR tool differentiates the responsibilities of the RN (assessment) versus the LPN (describing appearance), in this project LPNs completed the assessment portion of the document. Additionally, the majority of the calls to the medical providers were made by LPNs, as is common in nursing homes.16 While the project nursing home employs many experienced LPNs, their dominant role in SBAR completion and communication may have significantly influenced general medical decision-making of the nursing home residents. Given the fact that LPNs continue to play a major role in nursing homes, and that clinical assessment is not addressed in their education and scope of practice, there is a clinical and regulatory imperative to enact policy that supports safe and effective resident assessment by adequately trained professionals.19 Specifically, the need to evaluate the curricula of LPN educational programs to include observational techniques and documentation in nursing home residents is readily apparent and an area for future investigation.

3.3. Limitations

The small sample size of the quality improvement project conducted in a single-site limit the results. Additionally, there is the possibility that the responses of both nurses and physicians may have been influenced by recall bias. We did not measure/evaluate the actual clinical assessment conducted by the nurse or evaluate the completeness of the SBAR tool before the call was made to the medical provider. This would suggest a need for implementing a competency evaluation that assesses nursing proficiency in assessment and data collection, with utilization of complete data before telephone communication. Finally, patient outcomes including the rate of avoidable hospitalizations and clinical metrics were not evaluated, but are important considerations for future research. Clinical decision-making trees/rubrics would also assist the nurse with management strategies for acute changes in resident condition.

Despite limitations, this quality improvement project demonstrated that SBAR methodology is an efficient tool to communicate change in condition to medical providers and improve nurse to medical provider satisfaction with communication. Future research that evaluates the impact of SBAR methodology upon clinical outcomes and organizational measures such as cost are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Grant UL1 TR000038 from the National Center for the Advancement of Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Buchanan JL, Murkofsky RL, O’Malley AJ, et al. Nursing home capabilities and decisions to hospitalize: a survey of medical directors and directors of nursing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:458–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonner AF, Castle NG, Perera S, Handler SM. Patient safety culture: a review of the nursing home literature and recommendations for practice. Ann Longterm Care. 2008;16:18–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner L, Capezuti E, Rice JC. Nurses’ perceptions of safety culture in long-term care settings. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2009;41:184–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kayser-Jones JS, Wiener CL, Barbaccia JC. Factors contributing to the hospitalization of nursing home residents. Gerontologist. 1989;29:502–510. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.4.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt IK, Svarstad BL. Nurse-physician communication and quality of drug use in Swedish nursing homes. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1767–1777. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Perloe M. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations of nursing home residents: frequency, causes, and roots. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:627–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. Disruptive behavior and clinical outcomes: perceptions of nurses and physicians. Am J Nurs. 2005;105(1):54–64. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200501000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadogan MP, Franzi C, Osterweil D, Hill T. Barriers to effective communication in skilled nursing facilities: differences in perception between nurses and physicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:71–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dayton E, Henriksen K. Communication failure: basic components, contributing factors and the call for structure. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33:34–47. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hastings SN, Whitson HE, White HK, et al. After-hours calls from long-term care facilities in a geriatric medicine program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1989–1994. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNabney MK, Andersen RE, Bennett RG. Nursing documentation of telephone communication with physicians in community nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5:180–185. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000123027.01976.1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tjia J, Mazor KM, Field T, Meterko V, Spenard A, Gurwitz JH. Nurse-physician communication in the long-term care setting: perceived barriers and impact on patient safety. J Patient Saf. 2009;5:145–152. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181b53f9b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young Y, Barhydt NR, Boderick S. Factors associated with potentially preventable hospitalizations in nursing home residents in New York State: a survey of directors of nursing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:901–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beckett CD, Kipnis G. Collaborative communication: integrating SBAR to improve quality/patient safety outcomes. J Healthc Qual. 2009;31:19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2009.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Field TS, Tjia J, Mazor KM, et al. Randomized trial of a warfarin communication protocol for nursing homes: an SBAR-based approach. Am J Med. 2011;124:179.e1–179.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitson HE, Hastings SN, Lekan DA, Sloane R, White HK, McConnell ES. A quality improvement program to enhance after-hours telephone communication between nurses and physicians in a long-term care facility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1080–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunsford J. Structured communication: improving patient safety with SBAR. Nurs Womens Health. 2009;13:384–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-486X.2009.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall S, Harrison J, Flanagan B. The teaching of a structured tool improves the clarity and content of interprofessional clinical communication. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:137–140. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.025247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. SBAR Technique for Communication: A Situational Briefing Model. 2011 Available at: http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/PatientSafety/SafetyGeneral/Tools/SBARTechniqueforCommunicationASituationalBriefingModel.html. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velji K, Baker GR, Fancott C, et al. Effectiveness of an adapted SBAR communication tool for a rehabilitation setting. Healthc Q. 2008;11(Spec.):72–79. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2008.19653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castle NG, Sonon KE. A culture of patient safety in nursing homes. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(6):405–408. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.018424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamb G, Tappen R, Diaz S, Herndon L, Ouslander J. Avoidability of hospital transfers of nursing home residents: perspectives of frontline staff. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1665–1672. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haig KM, Sutton S, Whittington J. National patient safety goals. SBAR: a shared mental model for improving communication between clinicians. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32:167–175. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Tappen R. Interventions to reduce hospitalizations from nursing homes: evaluation of the INTERACT II collaborative quality improvement project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:745–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morse JM, Field PA. Qualitative Research Methods or Health Professionals. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dufrene C. Health care partnership: a literature review of interdisciplinary education. J Nurs Educ. 2012;51:212–216. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20120224-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hobgood C, Sherwood G, Frush K, et al. Teamwork training with nursing and medical students: dos the method matter? Results of an interinstitutional, interdisciplinary collaboration. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(25):1–6. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.031732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selle KM, Salamon K, Boarman R, Sauer J. Providing interprofessional learning through interdisciplinary collaboration: the role of “modeling”. J Interprof Care. 2008;22:85–92. doi: 10.1080/13561820701714755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cronewett L, Sherwood G, Pohl J, et al. Quality and safety education for nurses. Nurs Outlook. 2007;55:122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]