Abstract

Adolescent substance use is one of today’s most important social concerns, with Latino youth exhibiting the highest overall rates of substance use. Recognizing the particular importance of family connection and support for families from Mexican backgrounds, the current study seeks to examine how family obligation values and family assistance behaviors may be a source of protection or risk for substance use among Mexican-American adolescents. Three hundred and eighty-five adolescents (51% female) from Mexican backgrounds completed a questionnaire and daily diary for 14 consecutive days. Results suggest that family obligation values are protective, relating to lower substance use, due, in part, to the links with less association with deviant peers and increased adolescent disclosure. In contrast, family assistance behaviors are a source of risk within high parent-child conflict homes, relating to higher levels of substance use. These findings suggest that cultural values are protective against substance use, but the translation of these values into behaviors can be a risk factor depending upon the relational context of the family.

Keywords: family obligation, family assistance, substance use, cultural values, adolescence

Introduction

Adolescence is a time of heightened propensity for risk-taking, impulsivity, and reckless behavior that often leads to substance use initiation and abuse (Chambers, Taylor, & Potenza, 2003). Substance use underlies many behavioral and health problems that contribute to the public health burden during the adolescent period, including engagement in risky sexual practices, unwanted pregnancies, morbidity and mortality, violent behaviors, psychiatric problems, and high school drop out (Ellickson, Bui, Bell, & McGuigan, 1998; Fergusson, Horwood, & Swain-Campbell, 2002; Lancot & Smith, 2001). Ethnic and cultural influences play an important role in the prevalence of risk taking and substance use. Adolescents from Mexican backgrounds are at particular risk for engaging in maladaptive, risky behaviors. The overall rate of incarceration for Latino adolescents is 60% greater than for White non-Hispanic youth (Jones & Krisberg, 1994), Latino adolescents engage in more aggressive and delinquent behaviors compared to other ethnic groups, and Latino adolescents have higher rates of substance use, begin using drugs at an earlier age and show greater risk for developing drug use disorders in adulthood due to early drug use onset (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005; Johnston, et al., 2009; Marsiglia, Kulis, Wagstaff, Elek, & Dran, 2005). In order to address these ethnic disparities in substance use, there is great need for systematic research that examines cultural risk and protective factors for Latino youth who come from families that may possess beliefs and values that differ from the norms of American society (Smokowski & Bacallao, 2006; Parsai, Voisine, Marsiglia, Kulis, & Nieri, 2009). Recognizing the particular importance of family connection and support for families from Mexican backgrounds, the current study sought to examine how family obligation values (i.e., adolescents’ sense of responsibility to support and respect their family) and family assistance behaviors (i.e., adolescents’ provision of instrumental support to their family) may be a source of protection or risk for adolescent substance use. Moreover, we examined how the family context may modulate how family obligation values and family assistance behaviors are experienced.

Family Obligation Values and Family Assistance Behaviors

Families from Mexican backgrounds highly value family unity, support, and interdependence for daily activities (Suárez-Orozco, & Suárez-Orozco, 1995). Adolescents from Mexican backgrounds place a strong emphasis on family obligation – the psychological sense that one should help, respect, and contribute to their family (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999; Hardway & Fuligni, 2006). Mexican adolescents often feel a sense of duty to assist family members, to take into account the needs and wishes of their family when making important decisions, and to remain close to their family after high school (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999; Hardway & Fuligni, 2006).

Whereas family obligation values refer to the psychological sense of family support and respect, family assistance behaviors refer to the concrete acts of helping the family including caring for siblings, cleaning the home, translating for parents, and cooking meals (Telzer & Fuligni, 2009a). Compared to their European peers, youth from Mexican backgrounds spend almost twice as much time helping their family each day and assist their family 5-6 days per week on average (Telzer & Fuligni, 2009a; Telzer & Fuligni, 2009b), suggesting that family assistance is an important daily routine for these families.

Family obligation values and family assistance behaviors may differentially relate to substance use. Whereas family obligation values may be protective because of the psychological sense to be close to and respect the family, the very real need to provide assistance to the family on a daily basis, particularly under conditions of stress, potentially may be burdensome for adolescents and be linked to greater substance use. In the current study, we test the differential role of family obligation values and family assistance behaviors on Mexican-origin adolescents’ substance use.

Family Obligation Values and Substance Use

Family obligation values may be a cultural resiliency factor, protecting Mexican youth from substance use. Adolescents who internalize the values of their family may feel more connected to and embedded within a supportive family network, which can provide them with a sense of support and structure and help them select effective coping strategies to avoid substance use (Unger et al., 2002). Indeed, family obligation values are associated with a reduced likelihood of using drugs, delayed onset of drug use, and lower rates of externalizing problems among Latino youth (German, Gonzales, & Dumka, 2009; Gil, Wagner, & Vega, 2000; Kaplan, Napoles-Springer, Stewart, & Perez-Stable, 2001; Ramirez, et al., 2004; Romero & Ruiz, 2007; Unger, et al., 2002). Together, these findings underscore the important protective role that family obligation values play, and suggest that Latino youth may decide consciously to avoid drugs due to their sense of obligation to their family.

Potential Mediators of the Impact of Family Obligation Values on Substance Use

Despite recent findings demonstrating the protective nature of family obligation values, there have been no studies to examine potential mediators to explain the mechanisms by which family obligation values are protective. Two important factors that may influence adolescents’ substance use are deviant peer association and disclosure of activities to parents. Avoidance of deviant peers and staying out of trouble are important aspects of the family obligations of youth from Mexican backgrounds (Vega, Gil, Warheit, Zimmerman, & Apospori, 1993). A strong sense of obligation and respect for the family may reduce adolescents’ tendency to associate with deviant peers who engage in high risk behaviors, as such associations may reflect poorly on their family (German, et al., 2009). Peer affiliation and peer pressure are among the strongest predictors of substance use in adolescence (Barrera et al., 2002), and so identifying factors that reduce antisocial peer affiliation may be especially protective against substance use. For example, Brook and colleagues (1998) found that Puerto Rican adolescents whose peers used illegal drugs were also more likely to use drugs, but this association was mitigated when the adolescents endorsed high levels of family connection. Thus, family obligation may be related to decreased substance use because adolescents are more likely to avoid deviant peers.

In addition, youth who value family obligation are more likely to disclose their activities to their parents (Yau, Taspoulos-Chan, & Smethana, 2009), which may be protective against substance use. Adolescent disclosure is common among Mexican families, particularly in regards to personal activities, such as how adolescents spend their free time and which friends they hang out with (Yau et al., 2009). High levels of family obligation values may be rooted within a supportive family network, and this increased sense of family support may be related to more open communication (Unger, et al., 2002). Thus, youth high in family obligation values may feel stronger attachments to their family and use their family as a source of support and guidance (German, et al., 2009). Because adolescents spend increasingly less time under their parents’ supervision, more open disclosure of their activities may provide opportunities for parents to give their children advice and support, something they would be unable to provide without knowledge of their child’s behaviors (Kerr, Stattin, & Trost, 1999). Therefore, family obligation values may be related to decreased substance use because of adolescents’ tendency to have more open disclosure of their activities with their parents.

Family Assistance Behaviors and Substance Use

In contrast to research on family obligation values, no studies have examined the effects of actual family assistance behaviors on adolescent substance use. Whereas family obligation values have been associated consistently with positive outcomes, the actual act of providing support to the family can be stressful. Most prior work examining family assistance behaviors has focused on how it relates to youths’ psychological well-being (Kuperminc, Jurkovic, & Casey, 2009; Telzer & Fuligni, 2009a), physical health (Fuligni et al., 2009), and academic adjustment (Telzer & Fuligni, 2009b; East, Weisner, & Reyes, 2006), and no studies to date have examined how family assistance behaviors relate to youths’ substance use. The little research that has examined family assistance behaviors suggests that it is both a stressful and meaningful daily activity. For example, high levels of family assistance are related to feelings of burden but also to feeling like a good family member and feelings of happiness (Telzer & Fuligni, 2009a). Moreover, adolescents who spend more time providing child care for their families experience greater stress but also greater life satisfaction and a stronger orientation towards school (East et al., 2006). Thus, the implications of family assistance are complex, can be both positive and negative, and may depend on the context in which the family assistance behaviors take place.

The Role of the Context in which Family Assistance Behaviors Occur

The implications of family assistance behaviors may be negative when they take place within difficult family contexts, such as those characterized by economic strain, parent-child conflict, or when adolescents have low family obligation values. Family assistance within these more difficult contexts may be related to greater substance use because of the particularly demanding and stressful nature of the family assistance. Adolescents from economically strained families may experience family assistance as more burdensome. For example, adolescents among economically disadvantaged families who bear heavy household responsibilities often experience more difficult adjustment and stress including school maladjustment, poor parental relations, and psychological distress (Burton, 2007; McMahon & Luthar, 2007). Thus, family assistance among economically strained families may be experienced as stressful because these adolescents may not feel the sense of structure and support that is present in higher socioeconomic families.

In addition, the relational context of the family may be especially important for how family assistance is experienced. Because traditional Mexican family values stress the importance of family unity and social support, adolescents in high-conflict homes may feel disconnected from their family and experience an increased sense of burden when they assist their family. Family discord may be experienced as particularly disruptive for Mexican families who tend to emphasize strong family ties (Suárez-Orozco & Suárez-Orozco, 1995). These teens may act out by engaging in substance use as a way to cope with the negative relationships they have at home (McQueen, Getz, & Bray, 2003). In contrast, low conflict homes may be protective for youth as such teens may feel a greater sense of social support and connection when they assist their family.

Finally, adolescents’ values regarding family obligation may affect whether high levels of assistance are felt as a burden. If youth do not value helping their family but engage in high levels of family assistance, this could be an indicator of “cultural conflict,” which could create discord and distress (Zhou, 1997). In contrast, when adolescents highly value family obligation and engage in family assistance behaviors, they may feel closer to their family and experience a sense of reward and fulfillment that potentially could protect them from engaging in risky behavior, given the protective nature of family obligation values.

Current Study

In the current study, we examined the role of family obligation values and family assistance behaviors on Mexican-American adolescents’ substance use. High school is a critical time for drug use initiation and experimentation, such that lifetime drug use more than doubles and current drug use (i.e., use within the past 30 days) more than triples between 8th and 12th grade (Johnston et al., 2009). Therefore, we examine substance use among 9th and 10th grade Mexican adolescents. In contrast to most previous work on family obligation and substance use, which largely has focused on only one type of substance (e.g., cigarette use), we examined multiple types of substances including substances that are legal for adults (e.g., alcohol, cigarettes), marijuana, other illicit drugs (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin), and prescription drugs. This in-depth analysis of substance use allowed us to determine whether the effects of family obligation and family assistance on substance use replicate across different types of substances.

We sought to add to the literature in three key ways. First, we examined whether family obligation values and family assistance behaviors differentially predict substance use. Past research has shown that family obligation values are related consistently to less substance use (e.g., German, et al., 2009; Romero & Ruiz, 2007; Unger, et al., 2002), whereas family assistance behaviors are experienced as both burdensome and meaningful (Fuligni, et al., 2009; East et al., 2006; Telzer & Fuligni, 2009a). Therefore, we predicted that family obligation values and behaviors would function in unique ways, such that family obligation values would be protective, whereas the impact of family assistance behaviors would be more complex. Although consistent work has highlighted the protective role of family obligation values, the mechanisms by which they are protective are not well understood. Therefore, our second goal was to examine potential mediators that may explain, in part, why family obligation values relate to lower substance use, including adolescents’ tendency to avoid deviant peers and their likelihood to disclose their activities to their parents. Our third goal was to examine the role of the family context in which family assistance behaviors occur. Given the complex nature of providing actual family assistance behaviors, we expected that family assistance would be experienced differentially depending upon the family context. Within more difficult family contexts, such as those marked by economic strain, parent-child conflict, or when adolescents do not value family obligation, we expected family assistance to relate to greater substance use. In addition, we examined whether the family context impacts how family obligation values relate to adolescent substance use. Given that family obligation consistently has been related to dampened substance use across different studies with varying family contexts, we predicted that family obligation would be a protective factor against substance use regardless of the family context.

Method

Participants

Participants included 385 (51% female) 9th and 10th grade adolescents (Mage=15.01, SD=.82) and their primary caregiver from Mexican backgrounds. The primary caregivers who participated were predominantly the adolescents’ mother (83.1%), with 13.3% being the adolescents’ father, and the remaining 3.6% being grandparents, aunts, or uncles. The majority of adolescents were from immigrant families: 12.5% were of the first generation (i.e., adolescent and parents were born in Mexico), 68.5% were of the second generation (i.e., adolescent born in the U.S. but at least one parent was born in Mexico), and 19% were of third generation or greater (i.e., both the adolescent and parents were born in the U.S.). Participants were recruited from two public high schools in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. The student body of both schools was predominantly Latin American (62% and 94%) from lower- to lower-middle class families. In both schools, over 70% of students qualified for free and reduced meals (California Department of Education, 2011).

Procedure

Classroom rosters were obtained from the participating schools and then were allocated randomly for study recruitment across the school year. Each week, a few classrooms were visited, and presentations about the study were given to students. In the classroom presentations, students were told that the purpose of this study was to understand better the daily lives of families from Mexican backgrounds. In addition, consent forms were mailed to students’ homes, and phone calls to parents were made to determine interest and eligibility. Both the adolescent and the adolescents’ primary caregiver (i.e., the individual who spent the most time with the adolescent and knew about the adolescents’ daily activities) had to be willing to participate in the study and to report a Mexican background. A total of 428 families agreed to participate, representing 63% of families who were reached by phone and determined eligible for the study.

Our final sample of 385 families are those who provided complete data for all the variables in the current study, including family obligation values, family assistance behaviors, substance use, and all control variables (gender, generation, SES, family composition). Because each of our statistical models included every variable (i.e., both family obligation and family assistance were simultaneously entered into the regression model to predict substance use, with all control variables), we report only on these 385 families with complete data.

Interviewers visited the home of participants where the primary caregiver and adolescent provided consent/assent in accordance with the Institutional Review Board. Primary caregivers participated in a personal interview and the adolescent completed a self-report questionnaire, each of which took approximately 45-60 minutes to complete. All interviewers were bilingual in English and Spanish and administered the interview in whichever language the parent preferred. Seventy-one percent of parents completed the interview in Spanish. Only 1.6% of adolescents completed the self-report questionnaire in Spanish. Next, adolescents were provided with fourteen days of diary checklists to complete every night before going to bed for two subsequent weeks. The three page diary checklists took approximately five to ten minutes to complete each night. Adolescents were instructed to fold and seal each completed diary checklist each night and to stamp the seal with an electronic time stamper. The time stamper imprinted the current date and time and was programmed with a security code such that adolescents could not alter the correct time and date. Adolescents were told that if inspection of the data indicated that they had completed the checklists correctly and on time, each family would also receive two movie passes. At the end of the two week period, interviewers returned to the home to collect the diary checklists. Adolescents received $30 for participating and their primary caregiver received $50. The time-stamper monitoring and the cash and movie pass incentives resulted in a high rate of compliance, with 95% of the dairies being completed by adolescents.

Measures

Substance Use

Participants completed the Youth Risk Behavior Survey Questionnaire, a common measure of substance use that has been shown to be valid and reliable for Latino youth (Kerr, Beck, Shattuck, Kattar, & Uriburu, 2003; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1989). This in-depth questionnaire asks about current use (i.e., during the past 30 days, how many days did you use [substance]) for the following substances: cigarettes, alcohol (including beer, wine, wine coolers, and liquor, but does not include drinking a few sips of wine for religious purposes), marijuana (e.g., pot, weed, grass, hash, etc.), prescription drugs without a doctor’s prescription (e.g., Ritalin, oxycontin, Adderall, valium or any narcotic or tranquilizer), cocaine (e.g., powder, crack or freebase), crystal meth (also called “ice” or “glass”), and other illegal drugs (e.g., LSD, PCP, ecstasy, mushrooms, speed, or heroin). For cigarettes and alcohol, the response-scale ranged from 0-6 (0=0 days to 6=all 30 days), for marijuana the scale ranged from 0-6 (0=0 times to 6=100 or more times), and for other illicit drugs and prescription drugs, the scale ranged from 0-5 (0=0 times to 5=40 or more times). In the current study, we examined current use for 4 types of substances, including (1) substances that are legal for adults (e.g., tobacco and alcohol), (2) marijuana, (3) other illicit substances (e.g., cocaine, crystal meth, heroin, and speed), and (4) prescription drugs.

Family Obligation Values

Adolescents completed 12 items that assessed their attitudes regarding providing assistance to their family (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999), which has been previously used among Latino populations (Fuligni & Hardway, 2004). Using a 5-point scale (1=almost never to 5=almost always) adolescents indicated how often they felt they should assist with household tasks and spend time with their family, such as “help take care of your brothers and sisters,” “eat meals with your family,” and “spend time with your family on weekends.” The scale’s internal consistency was α=.81.

Family Assistance Behaviors

Each evening for fourteen days, adolescents indicated whether they had engaged in any of the following 9 activities: helped clean the apartment or house, took care of siblings, ran an errand for the family, translated for parents, helped siblings with their schoolwork, helped parents with official business (for example translating letters, completing government forms), helped to cook a meal for the family, helped parents at their work, and other. This list of activities was derived from focus group studies of adolescents and has been used successfully in previous studies with Mexican adolescents (e.g., Telzer & Fuligni, 2009b). From these 14 days of responses, we created an index, Family Assistance Behaviors, which represents the proportion of days out of 14 days that the adolescent reported helping his/her family by engaging in any one of the 9 assistance behaviors.

Deviant Peer Association

Participants indicated how many of their friends (1=none to 5=almost all) engaged in 15 deviant behaviors in the past month, such as got drunk or high, cheated on school tests, started a fight with someone, and stole something, using a measure previously used among Latino teenagers (Barrera, et al., 2002). All 15 items were averaged to create one index of Deviant Peer Association, which an internal consistency of α=.92.

Adolescent Disclosure

To examine adolescents’ willingness to disclose their activities to their parents, participants used a 5-point scale (1=almost never to 5=almost always) to respond to 5 items (Stattin & Kerr, 2000). For example, “do you hide a lot from your parents about what you do during nights and weekends” and “do you spontaneously tell your parents about your friends”. The scale’s internal consistency was α=.73.

Parent-Child Conflict

Adolescents responded to 10-items assessing the frequency of parent-child conflicts and arguments in their home in the past month using a measure previously employed among Latino teenagers (Ruiz, Gonzales, & Formoso, 1998). For example, “you and your parents yelled or raised your voices at each other,” “you and your parents ignored each other,” and “your parents let you know that they were angry or didn’t like something you said or did.” Adolescents used a 5-point scale ranging from 1=almost never to 5=almost always. The scale’s internal consistency was α=.86.

Economic Strain

The adolescents’ primary caregiver completed a measure indicating their families’ financial well being with 9 items that tapped economic strain over the past 3 months and has been previously used among Latino families (Conger et al., 2002; Dennis, Parke, Cotrane, Blacher, & Borthwick-Duffy, 2003). The primary caregiver indicated how much difficulty they had paying bills (1=no difficulty at all to 4=a great deal of difficulty), whether they had money left over at the end of each month (1=more than enough money left over to 4=very short of money), and whether they could afford different necessities such as food, medical care, and clothing (1=very true to 4=not at all true). The scale’s internal consistency was α=.90.

Socioeconomic Status and Family Composition

All analyses described in this article control for socioeconomic status and family composition. The primary caregiver reported their own and their child’s secondary caregiver’s (usually the father) highest level of education by responding to a scale that ranged from “elementary/junior high school,” “some high school,” “graduated from high school,” “some college,” “graduated from college,” to “law, medical, or graduate school.” The primary caregiver also reported their own and their child’s secondary caregiver’s occupation, which was then coded according to a five-point scale used in previous studies with a similar population (Telzer & Fuligni, 2009a) ranging from 1 (unskilled level) to 5 (professional level); examples of unskilled worker included such occupations as furniture mover, gas station attendant, food service worker, and housecleaner; semiskilled worker included baker, cashier, landscaper, and security guard; skilled worker included appraiser, barber, seamstress, and electrician; semiprofessional worker included nurse, librarian, optometrist, and office manager; and professional worker included architect, dentist, computer consultant, and physician. If the participant indicated a parent was unemployed, occupational status was not coded. Socioeconomic status was calculated by standardizing and averaging mothers’ and fathers’ education and occupation. In addition, the primary caregiver indicated characteristics of the family composition including number of siblings and adults in the household. See Table 1 for descriptives of participants’ family’s socioeconomic status and household structure.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic Background and Family Composition

| Variable |

N (Percent of sample) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mother’s Employment | ||

| Unemployed | 129 | (33.5) |

| Unskilled | 76 | (19.7) |

| Semi Skilled/Skilled | 116 | (30.1) |

| Semi Professional | 56 | (14.5) |

| Father’s Employment | ||

| Unemployed | 74 | (19.2) |

| Unskilled | 33 | (8.6) |

| Semi Skilled/Skilled | 188 | (48.8) |

| Semi Professional/Professional | 45 | (117) |

| Mother’s Education | ||

| Did not complete high school | 244 | (65.4) |

| Completed high school | 30 | (7.8) |

| Completed some college | 63 | (16.4) |

| Completed 2-year college | 20 | (5.2) |

| Completed 4-year college | 13 | (3.4) |

| Father’s Education | ||

| Did not complete high school | 250 | (72.9) |

| Completed high school | 42 | (10.9) |

| Completed some college | 25 | (6.5) |

| Completed 4-year college | 13 | (3.4) |

| Completed advanced degree | 13 | (3.4) |

| Family Composition | ||

| Dual parent household | 335 | (87.0) |

| Only child | 49 | (12.7) |

Note. Dual parent household represents whether there are at least 2 adults in the home. Of the 335 dual parent households, 178 had more than 2 adults.

Results

Descriptives

Family Assistance Behaviors and Family Obligation Values

Overall, 99% of adolescents helped on at least one day of the study. Helping with household tasks, such as cleaning, cooking, and running errands for the family was the most common type of activity reported by adolescents, occurring on 70% of days. Helping siblings by taking care of them and assisting them with their homework was the next most frequent type of activity (43% of days), followed by helping parents with official business and at their work (16.7% of days). Adolescents engaged in approximately 1.88 (SD = 1.25) types of assistance tasks per day and provided some type of assistance to the family on 79% of days. Approximately one-third of adolescents assisted their family on 100% of the study days, and 17.1% of adolescents assisted on 50% or fewer of the study days, 1% of whom assisted on 0 days.

Males and females did not differ in their family obligation values, but they did differ in their family assistance behaviors. Girls reported helping their family in any one of the types of assistance tasks on 82% of days whereas boys assisted on 76% of days, t(383)=2.44, p=.005. Males and females did not differ in the number of days they assisted their parents or siblings, but they did differ in the number of days they assisted with household tasks (females: 75.8% of days, males: 63.9% of days; t(383)=4.20, p<.001). There were no generational differences in family obligation values, whereas there were differences in family assistance behaviors. First-generation youth assisted their family on more days by engaging in any assistance task (88% of days) than second- (78.6% of days) or third- (74.9% of days) generation youth, F(2,382)=4.29, p<.05, η2=.02. Similar generational differences were found for assisting parents and assisting with household tasks. There were no generational differences in assisting siblings.

Family obligation and assistance did not differ depending on whether the household was a single versus dual parent household. Adolescents with more siblings tended to value family obligation more (r = .11, p < .05), assisted their family on more days overall (r = .13, p < .05), assisted siblings on more days (r = .27, p < .001), and assisted with household tasks on more days (r = .12, p < .05). Finally, family socioeconomic status was related only to assisting parents, such that adolescents from lower SES homes helped their parents on more days (r = .20, p < .001).

Substance Use

In terms of current use for the different substances, alcohol and cigarette use was the most common with nearly half of the sample reporting current use in the past month, followed by marijuana use with 30% of adolescents reporting current use. Other illicit substances were less common, with only 11% reporting current use, and prescription drugs were very rare, with less than 3% reporting current use (see Table 2). Given the very low frequency of prescription drug use, additional analyses do not include this substance.

Table 2.

Frequency of drug use for the 4 substance use categories.

| N | (Percent of sample) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Current Substance Use |

Alcohol or Cigarettes |

Marijuana | Other Illicit Drugs |

Prescription Drugs |

||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| 0 | 185 | (43.2) | 257 | (60.0) | 337 | (78.7) | 347 | (81.1) |

| 1 | 105 | (24.5) | 56 | (13.1) | 17 | (4.0) | 12 | (2.8) |

| 2 | 58 | (13.6) | 34 | (7.9) | 17 | (4.0) | 6 | (0.14) |

| 3 | 15 | (3.5) | 19 | (4.4) | 9 | (2.1) | 0 | |

| 4 | 8 | (1.9) | 10 | (2.3) | 5 | (1.2) | 0 | |

| 5 | 6 | (1.4) | 6 | (1.4) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | |

| 6 | 5 | (1.2) | 2 | (0.5) | ||||

Note.

Alcohol/Cigarettes: 0=0 days, 1=1-2 days, 2=3-5 days, 3=6-9 days, 4=10-19 days, 5=20-29 days, 6=all 30 days

Marijuana: 0=0 times, 1=1-2 times, 2=3-9 times, 3=10-19 times, 4=20-39 times, 5=40-99 times, 6=100 or more times.

Other Illicit Drugs and Prescription Drugs: 0=0times, 1=1-2 times, 2=3-9 times, 3=10-19 times, 4=20-39 times, 5=40 or more times

Males and females did not differ in their substance use. Substance use also did not differ according to parental socioeconomic status or household structure. In terms of generational status, first-generation youth were more likely to have higher marijuana use (M=1.08, SD=1.4) than third-generation youth (M=0.54, SD=1.10; F(2, 381)=3.22, p<.05) and more likely to have higher other illicit drug use (M=0.5, SD=1.07) than second-generation youth (M=0.21, SD=0.64), F(2,382)=3.04, p<.05.

Bivariate Correlations

Correlational analyses showed that family obligation values were associated with higher family assistance behaviors, less association with deviant peers, greater adolescent disclosure, lower cigarette/alcohol use, and lower marijuana use. Family assistance behaviors, on the other hand, were not related to substance use or to association with deviant peers, but were related to greater adolescent disclosure (Table 3).

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlations Between Family Obligation, Family Assistance, Substance Use, Deviant Peer Association, and Adolescent Disclosure

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family Obligation Values |

1 | ||||||

| 2. Family Assistance Behaviors |

.28*** | 1 | |||||

| 3. Deviant Peer Association |

−.15** | .01 | 1 | ||||

| 4. Adolescent Disclosure |

.40*** | .14** | −.30*** | 1 | |||

| 5. Alcohol/Cigarette Use |

−.26*** | .04 | .43*** | −.29*** | 1 | ||

| 6. Marijuana Use | −.15** | −.01 | .38*** | −.34*** | .55*** | 1 | |

| 7. Other Illicit Drug Use | −.07 | .05 | .29*** | −.19*** | .33*** | .40*** | 1 |

Note. p < .01,

p < .001.

Regressing Substance Use on Family Obligation Values and Family Assistance Behaviors

To test our primary hypotheses, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted. Our first research question examined whether family obligation values and family assistance behaviors differentially predict substance use. Family obligation values and family assistance behaviors were entered simultaneously to predict substance use for alcohol/cigarettes, marijuana, and other illicit drugs. This allowed us to examine how family obligation and family assistance relate to substance use above and beyond the effect of the other. Variables known to differentially relate to substance use or to vary by family obligation and family assistance were entered as controls (gender, generation, SES, family structure, age).

As shown in Table 4, family obligation values and family assistance behaviors were related differentially to substance use: family obligation values were related to lower levels of current use for each substance, whereas family assistance behaviors were associated only with higher cigarette/alcohol use. Family assistance behaviors were not associated with marijuana or other illicit drug use.

Table 4.

Regressing Family Obligation Values and Family Assistance Behaviors on Substance Use

| Cigarette/Alcohol Use |

Marijuana Use |

Illicit Drug Use |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| B(SE) | β | B(SE) | β | B(SE) | β | |

| Intercept | .28(1.27) | 1.07(1.27) | .75(.80) | |||

| Family Obligation Values |

−.37(.07)*** | −.29 | −.17(.07)** | −.14 | −.08(.04)* | −.10 |

| Family Assistance Behaviors |

.13(.07)* | .10 | .03(.07) | .02 | .06(.04) | .07 |

| First Generation | .40(.25) | .11 | .45(.25) | .12 | .37(.15)* | .16 |

| Second Generation | .04(.18) | .01 | .04(.18) | .02 | .07(.11) | .04 |

| Parental SES | .05(.09) | .03 | −.09(.09) | −.06 | .11(.05) | .11 |

| Gender | −.01(.13) | .01 | −.09(.13) | −.04 | .09(.08) | .06 |

| Single/Dual Parent Household |

.19(.19) | .05 | .19(.19) | .05 | .16(.12) | .07 |

| Number of Siblings | .03(.05) | .02 | −.02(.05) | −.02 | −.05(.03) | −.08 |

| Age | .00(.01) | .02 | −.00(.01) | −.02 | −.00(.00) | −.04 |

Note. p <.05,

p < .01,

p < .001. B represents the unstandardized regression coefficient with the corresponding standard error and β represents the standardized regression coefficient. Generation was dummy coded as first and second generations=1 such that third generation adolescents served as the reference group; Gender was coded females=1 males=0; SES=socioeconomic status, which was computed as the standardized mean of mother and father’s education and occupation; single/dual parent household was coded as single=1 dual=0; age was entered in months.

Mediating Family Obligation Values on Substance Use with Deviant Peer Association and Parental Disclosure

Given the consistent bivariate associations between family obligation values and substance use as well as family obligation values and adolescent disclosure and deviant peer association, we conducted mediation analyses to examine whether family obligation was protective due to adolescents’ greater disclosure to their parents and avoidance of deviant peers. We entered deviant peer association and adolescent disclosure into the same model described in Table 4. The mediation analyses were conducted by calculating the magnitude and the significance of the indirect effects of family obligation values on substance use, through deviant peer association and adolescent disclosure using commonly-used procedures recommended by MacKinnon and colleagues (MacKinnon & Fairchild, 2009; MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007).

As shown in Table 5, the original effect of family obligation values on substance use is reduced when deviant peer association and adolescent disclosure are entered into the model. Avoidance of deviant peers and adolescent disclosure accounted for 36.78% of the original effect of family obligation values on cigarette/alcohol use, 104.41% of the original effect on marijuana use (suggesting a small suppression effect), and 85.35% of the original effect on other illicit drug use. Therefore, the greater tendency of adolescents with higher family obligation values to disclose to their parents and associate with fewer deviant peers accounts for a significant proportion of the tendency for adolescents with higher family obligation values to have lower substance use.

Table 5.

Mediating Family Obligation Values on Substance Use with Deviant Peer Association and Parental Disclosure

| Total Effect (C) |

Direct Effect (C‘) |

Indirect Effect of Deviant Peer Association (M1) and Adolescent Disclosure (M2) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| Substance Use Outcome |

B | SE | B | SE | R2△ | B | SE | Z | % of total effect |

95% confidence limit |

| Cigarettes/ Alcohol |

−.37*** | .07 | −.23*** | .06 | .16*** | .07 .06 |

.02 .01 |

2.99*** 6.33*** |

20.25% 16.53% |

[−.13, −.02] [−.11, −.02] |

| Marijuana | −.17** | .07 | .01 | .06 | .18*** | .06 .12 |

.02 .02 |

2.99*** 6.76*** |

34.41% 70.00% |

[−.10, −.02] [−.18, −.07] |

| Other Illicit Drugs |

−.08* | .04 | −.01 | .04 | .09*** | .03 .04 |

.01 .01 |

2.99*** 6.60*** |

40.38% 44.87% |

[−.06, −.01] [−.07, −.01] |

Note. p <.05,

p < .01,

p < .001. All analyses control for gender, socioeconomic status, family composition, and generational status. B refers to the unstandardized coefficient. C refers to total effect of Family Obligation Values on Substance Use (i.e., the original effect as shown in Table 4). C‘ refers to the direct effect of Family Obligation Values on Substance Use after accounting for both the mediators, Deviant Peer Association (M1) and Parental Disclosure (M2). Indirect effect refers to the effects of Family Obligation Values on Substance Use through Deviant Peer Association (M1) and Adolescent Disclosure (M2). R2△ represents the change in R2 when the mediators are entered into the model. The percentage of the total effect of Family Obligation Values on Substance Use was determined by dividing the indirect effect of Family Obligation Values on Substance Use through Deviant Peer Association and Parental Disclosure by the total effect of Family Obligation Values on Substance Use. Z refers to the tests of the statistical significance of the indirect effects, and the percentage of total effect refers to the proportions of the total effects that were accounted for by the indirect effects. The confidence limit represents the asymmetric confidence limits based on the distribution of products (MacKinnon et al., 2007). The confidence intervals of the indirect effects do not include zero,consistent with statistically significant mediation.

Examining the Context in Which Family Assistance Behaviors and Family Obligation Values Occur

Next, to examine whether the association of family obligation values and family assistance behaviors with substance use depended upon the context of the family, we entered interaction terms into the regression model described in Table 4. We examined three potential contextual variables including economic strain, parent-child conflict, and adolescents’ family obligation values. Using the guidelines of Aiken and West (1991) to estimate interaction effects in multiple regression, we computed interaction terms by centering the moderator variables and multiplying them by the centered version of family assistance behaviors and family obligation values. The interaction terms were then entered into multiple regression analyses along with the centered moderators, family assistance, and family obligation to predict substance use. Gender, generation, socioeconomic status, and family composition were included as controls.

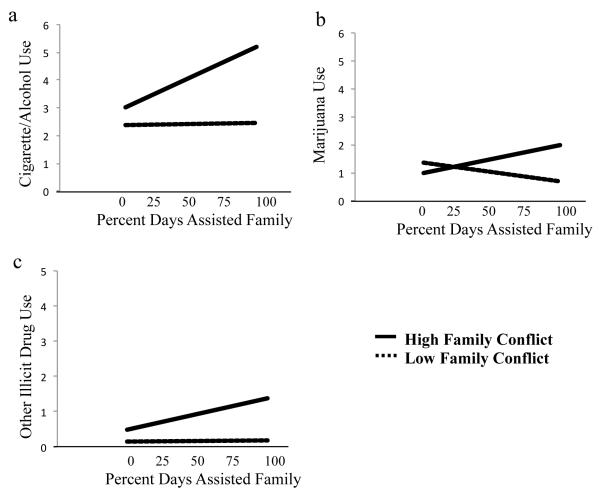

Family conflict significantly moderated the association between family assistance behaviors and all three substance use outcomes (cigarettes/alcohol: B=.15, SE=.07 β=.11, p<.05; marijuana: B=.19, SE=.07 β=.15, p<.01; other illicit drugs: B=.12, SE=.05 β=.14, p<.05). We probed the significant interactions by examining the simple slopes of family assistance behaviors on substance use at family conflict levels 1 SD below and above the mean (Aiken & West, 1991). As shown in Figure 1a-c, family assistance behaviors within high parent-child conflict homes (i.e., 1 SD above the mean) were associated with greater cigarette/alcohol use (b=2.18), marijuana use (b=.98), and other illicit drug use (b=.90). In contrast, family assistance behaviors within families marked by low parent-child conflict (i.e., 1 SD below the mean) were not associated with cigarette/alcohol use (b=.09) or other illicit drug use (b=.03) but were associated with lower marijuana use (b=-.69). Economic strain and family obligation values did not moderate the association between family assistance behaviors and substance use.

Figure 1.

Family conflict moderates the association between family assistance behaviors and (a) cigarette/alcohol use, (b) marijuana use, and (c) other illicit drug use such that family assistance is associated with higher substance use in high conflict families.

We also examined whether the family context moderated the association between family obligation values and substance use. We found only one significant moderation, such that family obligation values were protective against other illicit drugs in high-conflict homes (b=-.19) but were not associated with drug use in low conflict homes (B=-.09, SE=.04 β=-.11, p<.05).

Discussion

Adolescent substance use is one of today’s most important health problems and may be particularly problematic among Mexican-origin youth. Attending to the health of this growing population should be a central concern and seen as an investment in the health of the country (Ojeda, Patterson, & Strathdee, 2008). Thus, it is essential to identify protective factors that may reduce adolescents’ health risk behaviors and mollify ethnic disparities in substance use. Recent recommendations by child development researchers have stressed the importance of focusing on culturally relevant risk and protective factors that may foster positive adjustment among ethnic minority youth (Smokowski & Bacallao, 2006; Parsai et al., 2009). Consistent with this recommendation, we examined how a culturally important aspect of family relationships among adolescents from Mexican backgrounds may serve as a source of protection or risk for adolescent substance use. Results suggest that family obligation values are protective for Mexican adolescents’ substance use, whereas family assistance behaviors are both a source of risk and resilience, depending upon the relational context of the home.

Family Obligation Values and Substance Use

Consistent with prior work, we found that family obligation values are protective, relating to lower substance use. In contrast to most previous work, which largely has focused on only one type of substance, we examined multiple types of substances, including alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, and other illicit drugs (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin). We found that adolescents with greater family obligation values reported lower use of cigarettes and alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drugs. Although several studies have highlighted the protective role that family obligation values play for adolescents’ health risk behaviors (e.g., German, et al., 2009; Ramirez, et al., 2004; Romero & Ruiz, 2007; Unger, et al., 2002), we know little about the mechanisms by which it is protective. In the current study, we found that family obligation values were associated with lower levels of substance use because adolescents were less likely to associate with deviant peers and more likely to disclose their activities to their parents. Although our data are cross-sectional and do not provide information about the direction of the effects over time, these findings are suggestive of mediation.

Greater family obligation values may help adolescents to feel more connected to and supported by their family. Adolescents with greater family obligation values may be more willing to share their daily experiences with their family (Yau et al., 2009). Such disclosure may open up family discussions about appropriate behavior and strategies for dealing with peer pressure. Adolescents spend increasingly more time away from their parents’ supervision. When adolescents disclose their activities to their parents, such as where they go after school or what they did with their friends on the weekend, parents are more likely to understand the types of situations their children become involved in, who their children spend time with, and how responsibly they may act in different situations (Kerr, et al., 1999). Parents can then provide advice and support, helping their child develop coping strategies to avoid substance use. Higher levels of disclosure between teens and parents also can help adolescents understand the importance of family obligation – to experience it directly in close relationships with others.

Adolescents who value family obligation may avoid deviant peers because such peer relationships would reflect poorly upon their family (German, et al., 2009), or they may not need the connections to peers because family members already provide close connections. Negative peer pressures are one of the strongest predictors of adolescents’ substance use. Therefore, family obligation may decrease adolescents’ tendency to associate with peers who engage in high risky behaviors and such peer avoidance may be a strong protective factor against substance use (Barrera, et al., 2002).

We found evidence of moderation for one of the substance use outcomes, such that family obligation values were especially protective against other illicit drug use in high-conflict homes. Given that only one interaction was significant, and for the substance with the lowest reported frequency (less than 12%), we interpret the finding with caution. The interaction suggests that when adolescents report high levels of family conflict, strong family obligation values may be particularly protective. In contrast to the moderation findings for family assistance behaviors, family obligation values were protective in high conflict homes, whereas assistance behaviors were particularly detrimental. This is consistent with the main effects of the regressions, such that family obligation values were consistently positive for adolescents, whereas assistance behaviors were more often a source of stress. Therefore, family obligation is a protective factor in high conflict homes, whereas family assistance exacerbates the detrimental effect of family conflict.

Family Assistance Behaviors and Substance Use

To our knowledge, no previous research has examined how family assistance behaviors relate to adolescents’ substance use. Our findings suggest that family assistance behaviors function in qualitatively different ways than family obligation values. Whereas family obligation values were largely beneficial for all adolescents, family assistance behaviors were found to be a risk factor for some adolescents. We found a main effect for cigarette and alcohol use, such that higher levels of family assistance were associated with greater substance use. This effect was further qualified by an interaction, such that family assistance was related to higher levels of cigarette and alcohol use only when the assistance took place within high-conflict homes. We found similar moderations for marijuana and other illicit drug use. Moreover, family assistance in low conflict homes tended to be associated with lower levels of marijuana use. These results suggest that family assistance is experienced as both demanding and stressful at times, but also is meaningful (Burton, 2007; Fuligni, et al., 2009; Telzer & Fuligni, 2009a, Telzer & Fuligni, 2009b).

Parent-child conflict may be especially distressing among families from Mexican backgrounds who tend to emphasize strong family solidarity and connection (Suarez-Orozco & Suarez-Orozco, 1995). Mexican adolescents who report more frequent conflicts with their parents may feel disconnected from their family, experience an increased sense of burden when they assist their family, and feel greater emotional distress, which can lead to heightened substance use (Tschann et al., 2002). Thus, these teens may enact poor coping mechanisms and act out by engaging in substance use as a way to deal with the conflicts they may feel at home (McQueen, et al., 2003). In contrast, low conflict homes may be protective for youth as such teens may feel a greater sense of social support and connection when they assist their family, particularly for Mexican families who value positive family relationships. Thus, lower family discord may provide a more positive family environment and foster a sense of happiness and satisfaction from assisting the family. These teens may feel closer to their family and try to maintain positive family relations by avoiding substance use.

We did not find that the economic context of the household affected how family assistance behaviors were experienced. Although adolescents assisted their family more when they came from families with higher economic strain, this was not related to their substance use. Interestingly, economic strain itself was not related to substance use, suggesting that being poor, in and of itself, is not necessarily a risk factor for substance use. Although previous work has found that adolescents among economically disadvantaged families experience adjustment difficulties when they assist their family (Burton, 2007), our results suggest that this does not translate into substance use problems. Perhaps adolescents in economically strained households understand that their assistance is essential for the well-being of their family and thus do not act out by engaging in risky behavior such as substance use. In contrast to the cultural conflict they may experience when they are in high-conflict homes, higher levels of family assistance behaviors within economically disadvantaged families may be experienced as culturally congruent because the adolescents understand the importance of their family assistance for the well-being of their family. These adolescents may still experience a sense of burden and distress (Burton, 2007), but they may avoid behaviors that could hurt the family.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study examined how family obligation values and family assistance behaviors are related to Mexican adolescents’ substance use. Future studies should examine whether family obligation is also protective for Asian youth who also tend to place great emphasis on family solidarity and support (Fuligni et al., 1999) or for those families from any cultural background who, relative to others, emphasize family obligation. Additionally, researchers should continue to identify other culturally relevant factors that may be protective against adolescent substance use, such as parental involvement in school activities, religious participation and beliefs, positive peer relationships, and participation in meaningful activities such as after school programs or sports teams. Because youth from different cultures place different emphasis on family, peers, and school, these agents may differentially affect youths’ substance use and risk taking behaviors.

In terms of group differences in substance use, we found that first-generation youth tended to report greater substance use than second-generation youth. Most prior work has found that second and third-generation youth are more likely to use drugs, perhaps due to acculturation (e.g., Peña, Wyman, Brown, Matthieu, Oliveras, Hartel, & Zayas, 2008). It is not clear why we find the opposite pattern, but given that only 48 adolescents in the current study were of first-generation, we do not make too much of this finding. Consistent with prior research on Latino adolescents (Flannery, Vazsonyi, Torquati, & Fridrish, 1994), we did not find evidence of gender differences in substance use. However, other work has found gender differences, such that males report greater use than females (e.g., Dukarm, Byrd, Auinger, & Weitzman, 1996). Thus, future studies should systematically examine gender differences in substance use across cultural groups in order to understand more carefully when gender differences arise (e.g., for particular substances only, for frequency of use, etc.).

Given the cross-sectional nature of the study, we are unable to determine whether family obligation values lead to lowered substance use or whether adolescents who engage in higher substance use experience dampened ties to their family over time. Future longitudinal research should examine the direction of these effects, adjusting for the stability of drug use over time. Identifying the direction of the effects could inform interventions designed to reduce substance use. If longitudinal research found that family obligation values and family assistance behaviors indeed lead to adolescent substance use, interventions could be designed to focus on increasing cultural values of family obligation but at the same time focusing on the relational qualities within the home such that the translation of these values into behaviors are not experienced as stressful.

It should be noted that most of the measures were reported by the adolescents. It is possible that adolescents misperceive family tensions and report higher levels of family conflict. Parents and adolescents often perceive very different relational contexts in their home, with adolescents perceiving higher and more accurate levels of conflict than mothers (Gonzales, Cauce, & Mason, 1996). Adolescents’ perceptions of conflict likely have a greater impact on their behaviors than do parents’ perceptions of conflict. Moreover, adolescents may under- or overestimate their substance use. Nonetheless, the frequency of drug use found in the current study is consistent with national reports (Johnston et al., 2009).

Family obligation and assistance have important, yet distinct, implications for substance use among adolescents from Mexican backgrounds. As a result, it is essential for programs designed for this population to consider how support of the family presents both strengths and challenges. Without considering both the risks and benefits that family obligation and assistance can provide, interventions designed to reduce substance use actually may have iatrogenic effects because of the variability in the dynamics of family obligation and assistance among those from Mexican backgrounds. For instance, interventions that focus on promoting a sense of obligation to the family might result in high levels of assistance that, for some adolescents in some families, may have negative implications for substance use. Thus, interventionists should carefully consider the consequences of both values and behaviors for adolescents’ well-being.

Conclusions

This study contributes to our understanding of how cultural values and behaviors relate to adolescents’ health risk behaviors broadly, and specifically how these cultural resources can be both beneficial and costly for Mexican adolescents’ substance use behaviors. We examined an aspect of family life that is culturally relevant to Mexican families. By taking this approach, we were able to identify a “cultural resource” (German et al., 2009) for these families, identifying how and when family obligation and family assistance can be a protective or risk factor. Our findings can contribute to culturally grounded interventions that utilize resiliencies inherent in Mexican culture (Hecht, Marsiglia, Elek, Wagstaff, Kulis, Dustman, & Miller-Day, 2003).

In conclusion, family obligation and assistance are fundamental aspects of family life and have important implications for substance use among adolescents from Mexican backgrounds. Our findings suggest that Mexican adolescents’ decisions to engage in substance use may depend upon their cultural values and behaviors. Mexican adolescents’ beliefs in supporting and spending time with their family are protective against substance use. Yet, despite their strong family obligation values, family assistance behaviors can sometimes be costly, relating to greater substance use when assistance takes place within high-conflict homes.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Jr., Prelow HM, Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Michaels ML, Tein JY. Pathways from family economic conditions to adolescents’ distress: Supportive parenting, stressors outside the family and deviant peers. Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30(2):135–152. doi: 10.1002/jcop.10000. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Balka EB, Win PT, Gursen MD. Drug use among Purto Ricans: Ethnic identity as a protective factor. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1998;20:241–254. doi: 10.1177/07399863980202007. [Google Scholar]

- Burton L. Childhood adultification in economically disadvantaged families: A conceptual model. Family Relations. 2007;56(4):329–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00463.x. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Summaries – United States, 2005. MMWR 2006. 2005;55(SS-5) Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss5505a1.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R, Taylor J, Potenza M. Developmental neurocircuitry of motivation in adolescence: A critical period of addiction vulnerability. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1041–1052. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ebert Wallace L, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(2):179–193. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.2.179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukarm CP, Byrd RS, Auinger P, Weitzman M. Illicit substance use, gender, and the risk of violent behavior among adolescents. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 1996;150:797. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170330023004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis JM, Parke RD, Coltrane S, Blacher J, Borthwick-Duffy SA. Economic pressure, maternal depression, and child adjustment in Latino families: An exploratory study. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2003;24:183–202. [Google Scholar]

- East PL, Weisner TS, Reyes BT. Youths’ caretaking of their adoelscent sisters’ children: Its costs and benefits for youths’ development. Applied Developmental Science. 2006;10:86–95. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads1002_4. [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Bui K, Bell R, McGuigan KA. Does early drug use increase the risk of dropping out of high school? Journal of Drug Issues. 1998;28(357-380) [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell N. Cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97:1123–1135. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00103.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery DJ, Vazsonyi AT, Torquati J, Fridrich A. Ethnic and gender differences in risk for early adolescent substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1994;23:195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Hardway C. Preparing diverse adolescents for the transition to adulthood. The Future of Children. 2004:99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Telzer EH, Bower J, Irwin MR, Kiang L, Cole SR. Daily family assistance and inflammation among adolescents from Latin American and European backgrounds. Brian, Behavior, and Immunity. 2009;23:803–809. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.02.021. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents from Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70(4):1030–1040. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00075. [Google Scholar]

- German M, Gonzales NA, Dumka L. Familism values as a protective factor for Mexican-origin Adolescents exposed to deviant peers. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29:16–42. doi: 10.1177/0272431608324475. doi: 10.1177/0272431608324475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Tubman JG. Associations between early-adolescent substance use and subsequent young-adult substance use disorders and psychiatric disorders among a multiethnic male sample in South Florida. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1603–1609. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Vega WA. Acculturation, familism and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: Longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(4):443–458. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(200007)28:4<443::AIDJCOP6>3.0.CO;2-A. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Cauce AM, Mason CA. Interobserver Agreement in the Assessment of Parental Behavior and Parent - Adolescent Conflict: African American Mothers, Daughters, and Independent Observers. Child Development. 2008;67:1483–1498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardway C, Fuligni AJ. Dimensions of family connectedness among adolescents with Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(6):1246–1258. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1246. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2008: Volume I, Secondary school students (NIH Publication No. 09-7402) National Institute of on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jones MA, Krisberg B. Images and reality: Juvenile crime, youth violence, and public policy. National Council on Crime and Delinquency; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan CP, Napoles-Springer A, Stewart SL, Perez-Stable EJ. Smoking acquisition among adolescents and young Latinas: the role of socioenvironmental and personal factors. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:531–550. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00143-x. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(00)00143-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr MH, Stattin H, Trost K. To know you is to trust you: parents’ trust is rooted in child disclosure of information. Journal of Adolescence. 1999;22:737–752. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0266. doi:10.1006/jado.1999.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr MH, Beck K, Downs Shattuck T, Kattar C, Uriburu D. Family involvement, problem and prosocial behavior outcomes of Latino youth. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27:S55–S65. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperminc GP, Jurkovic GJ, Casey S. Relation of filial responsibility to the personal and social adjustment of Latino adoelscents from immigrant families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:14–22. doi: 10.1037/a0014064. doi: 10.1037/a0014064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancot N, Smith CA. Sexual activity, pregnancy, and deviance in a representative sample of African American girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2001;30:349–372. doi: 10.1023/A:1010496229445. [Google Scholar]

- Lovato CY, Litrownik AJ, Elder J, Nunez-Liriano A, Suarez D, Talavera GA. Cigarette and alcohol use among migrant Hispanic adolescents. Family and Community Health. 1994;16:18–31. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavioral Research Methods. 2007;39:1–12. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ. Current directions in mediation analysis. Psychological Science. 2009;18:16–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01598.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Wagstaff DA, Elek E, Dran D. Acculturation status and substance use prevention with Mexican and Mexican-American youth. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2005;5:85–111. doi: 10.1300/J160v5n01_05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon TJ, Luthar SS. Defining characteristics and potential consequences of caretaking burden among children living in poverty. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77:267–281. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.267. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen J, Getz JG, Bray J, H. Acculturation, substance use, and deviant behavior: Examining separation and family conflict as mediators. Child Development. 2003;74:1737–1750. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00635.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Judd C, M., Yzerbyt V, Y. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:852–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda VD, Patterson TL, Strathdee SA. The influence of percieved risk to health and immigration-related charateristics on substance use among Latino and other immigrants. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;76:525–531. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.108142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsai M, Voisine S, Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Nieri T. The protective and risk effects of parents and peers on the substance use attitudes and behaviors of Mexican Americans female and male adolescents. Youth and Society. 2009;40:353–376. doi: 10.1177/0044118X08318117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña JB, Wyman PA, Brown CH, Matthieu MM, Olivares TE, Hartel D, Zayas LH. Immigration generation status and its association with suicide attempts, substance use, and depressive symptoms among Latino adolescents in the USA. Prevention Science. 2008;9:299–310. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0105-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JR, Crano WD, Quist R, Burgoon M, Alvaro EM, Grandpre J. Acculturation, familism, parental monitoring, and knowledge as predictors of marijuana and inhalant use in adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(1):3–11. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.3. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Ruiz M. Does familism lead to increased parental monitoring?: Protective factors for coping with risky behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16:143–154. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9074-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz SY, Gonzales NA, Formoso D. Multicultural, multidimensional assessment of parent-adolescent conflict. Paper presented at the Seventh Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence; San Diego. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Bacallao ML. Acculturation, internalizing mental health symptoms, and self-esteem: Cultural experiences of Latino adolescents in North Carolina. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2006;2007:273–292. doi: 10.1007/s10578-006-0035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development. 2000;71(4):1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Suárez-Orozco MM. Transformations: Immigration, family life, and achievement motivation among Latino adolescents. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Fuligni AJ. Daily family assistance and the psychological well being of adolescents from Latin American, Asian, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2009a;45:1177–1189. doi: 10.1037/a0014728. doi:10.1037/a0014728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Fuligni AJ. A longitudinal daily diary study of family assistance and academic achievement among adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009b doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9391-7. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschann JM, Flores E, Marin BV, Pasch LA, Baisch EM, Wibblesman C, J. Interparental conflict and risk behaviors among Mexican American adolescents: a cognitive-emotional model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:373–385. doi: 10.1023/a:1015718008205. doi: 10.1023/A:1015718008205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Teran L, Huang T, Hoffman BR, Palmer P. Cultural values and substance use in a multiethnic sample of California adolescents. Addiction Research and Theory. 2002;10:257–279. doi:10.1080/16066350211869. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Gil AG, Warheit GJ, Zimmerman RS, Apospori E. Acculturation and delinqient behavior among Cuban American adolescents: Toward an emperical model. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:113–125. doi: 10.1007/BF00938210. doi: 10.1007/BF00938210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau JP, Taspoulos-Chan M, Smethana JG. Disclosure to parents about everyday activities among American adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 2009;80:1481–1498. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01346.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M. Growing up American: The challenge confronting immigrant children and children of immigrants. Annual Review of Sociology. 1997;23:63–95. [Google Scholar]