Abstract

Here, we review the early studies on cGMP, guanylyl cyclases, and cGMP-dependent protein kinases to facilitate understanding of development of this exciting but complex field of research encompassing pharmacology, biochemistry, physiology, and molecular biology of these important regulatory molecules.

Keywords: Guanylyl cyclase, cGMP, Protein kinase G, Phosphodiesterase

“I have but one lamp by which my feet are guided, and that is the lamp of experience. I know no way of judging of the future but by the past.”

Edward Gibbon

1 Introduction

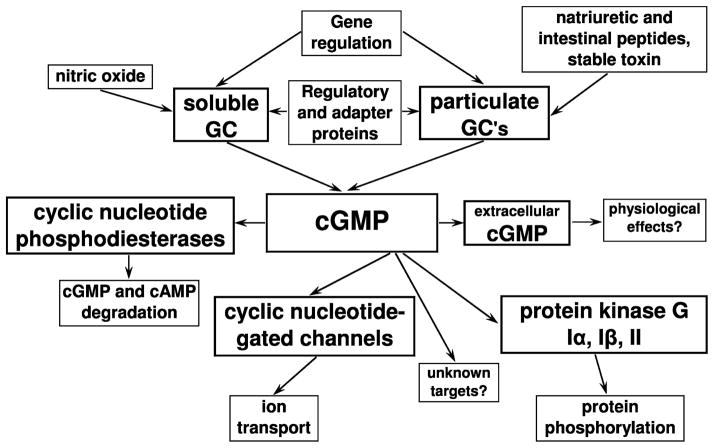

This chapter describes a number of historical aspects of discoveries made in the fields of cGMP research. To facilitate the understanding of signaling pathways, we have included a general scheme of these pathways in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Scheme of cGMP signaling pathways. Soluble and particulate guanylyl cyclases (GC) are stimulated mainly by nitric oxide and natriuretic and intestinal peptides and stable toxin from Escherichia coli, respectively. These enzyme are known to be regulated on the expression level (gene regulation) and by certain regulatory and adapter proteins. They synthesize cGMP, which can be degraded by cGMP-specific phosphodiesterases or transported to the extracellular environment via specific mechanism. The main targets of cGMP-dependent regulation include cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases (cAMP- and cGMP-specific), cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels and cGMP-dependent protein kinases (protein kinase G)

The primary scope of this chapter is to outline the main events in the field of cGMP, but not to cite every important publication. The authors sincerely apologize to all scientists whose important papers are not cited here due to size limitations.

2 Discovery of cGMP, Guanylyl Cyclases, and cGMP Phosphodiesterases

Since the discovery of cAMP (Rall and Sutherland 1958; Sutherland and Rall 1958), it had become evident that other 3′, 5′ cyclic nucleotides might exist and that these compounds might be important for regulation of cellular physiology. In 1960, cGMP was synthesized for the first time (Smith et al. 1961) and synthetic compound was shown to be degraded by enzymatic hydrolysis similar to cAMP (Drummond and Perrott-Yee 1961). An enzyme capable of digesting the 3′–5′ phosphodiester bond of cGMP was detected also by Kuriyama et al. (1964). At about same time, existence of endogenously produced cGMP was confirmed by isolation and identification of cGMP from rabbit urine (Ashman et al. 1963). Later, this was confirmed by another study from the same laboratory (Price et al. 1967), which analyzed specific activity of urinary cGMP in rats treated with [32P]phosphate and suggested that cGMP is synthesized in a reaction catalyzed by a cyclase, which might be similar to previously discovered adenylyl cyclase. In the laboratory of Earl Sutherland, hormonal regulation of urinary cGMP levels was investigated and it was found that a number of steroid, thyroid, and pituitary hormones can regulate production of cGMP in rats (Hardman et al. 1966). This work was paralleled by a study in which a phosphodi-esterase specific for cAMP and cGMP was isolated and partially purified from dog heart (Nair 1966) with subsequent publications revealing more insight into cGMP-specific phosphodiesterases (Beavo et al. 1970; Cheung 1971; Kakiuchi et al. 1971; Thompson and Appleman 1971). At this point, considering early publications on cGMP secretion (Hardman et al. 1966; Broadus et al. 1971; also reviewed by Sager 2004), it became apparent that steady state levels of cGMP in cells and tissues are determined by the balance of cGMP synthesis by guanylyl cyclases and cGMP extrusion out of the cell and degradation by phosphodiesterases. It was also demonstrated that cGMP has certain pharmacological effects (for example, see Murad et al. 1970) and later studies pointed to possible regulation of cGMP levels by various hormones (again, just an example, Kimura et al. 1974).

Rapid progress in the field was possible because of the development of an accurate radioimmunoassay for cGMP (Brooker et al. 1968). In 1969, guanylyl cyclase activity was described (Bohme et al. 1969; Hardman and Sutherland 1969; Schultz et al. 1969; White and Aurbach 1969).

At the same time, it also became apparent that guanylyl cyclases exist as a number of isoforms, some of which are soluble while others are membrane-bound or might associate with the cytoskeleton (Goridis and Morgan 1973; Kimura and Murad 1974, 1975a, b). In this case, the situation was quite different from adeny-lyl cyclase research. Hormones and mediators capable of activating adenylyl cyclase have been known for quite a while, whereas what physiologically relevant molecules induce activation of guanylyl cyclases remained quite a mystery. Earl Sutherland wrote in his Nobel lecture in 1971 comparing the research areas of cAMP and cGMP: “Then (implying cAMP) we had a function, and found a nucleotide; now (implying cGMP) we have a nucleotide, and are trying to discover its function” (published online at nobelprize.org).

Several hormones and neuromediators were described to influence the activities of guanylyl cyclases in intact cells, but there was no direct evidence of activation of this enzyme. The problem at that time was that some key regulators were not yet discovered. And the routes to their discoveries took several years and were not always straightforward. Exciting examples of such mediators are nitric oxide, endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF), and atriopeptins.

3 History of Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase

There is an abundant literature on the subject of nitric oxide as endogenous messenger and for more detailed description of this topic, the readers are referred to other publications (for example, see Murad et al. 1978; Moncada 1990; Murad 1998, 1999, 2006; Yetik-Anacak and Catravas 2006).

Essentially, the mystery of soluble guanylyl cyclase and nitric oxide can be split in several key issues. First, during early studies, it was shown that calcium infusions stimulate excretions of cGMP and not cAMP with urine (Kaminsky et al. 1970). In addition to this, it was shown that acetylcholine can increase the levels of cGMP indirectly in isolated perfused rat heart (George et al. 1970) and that calcium is important for regulation of cGMP levels in tissues (Schultz et al. 1973). Another aspect of the puzzle involved activation of the soluble isoform of guanylyl cyclase by nitric oxide, which can be generated from other activators such as azide, nitrate, and hydroxylamine (Kimura et al. 1975a, b) in the presence of catalase and by nitrovasodilators (Arnold et al. 1977; Katsuki et al. 1977). These two aspects seemed to be completely unrelated to each other and they remained so for another 10 years. Meanwhile, relaxation of blood vessels by acetylcholine was shown to be endothelium-dependent and to involve another mysterious factor, EDRF, which acted on an unidentified target in smooth muscle cells (Furchgott and Zawadzki 1980). It was soon shown that EDRF increases cGMP synthesis in isolated blood vessels and increases protein phosphorylation in smooth muscle (Rapoport et al. 1983; Rapoport and Murad 1983). Later on, it was suggested that EDRF can be an endogenous nitrovasodilator (Murad 1986). This was subsequently followed by physiological and biochemical studies showing a very close chemical and pharmacological similarity of EDRF and nitric oxide (reviewed in Ignarro 1989). On the other hand, previously, it was shown that L-arginine could activate crude or partially purified soluble guanylyl cyclase but had no effect on purified enzyme, (Deguchi and Yoshioka 1982) which indicated that partially purified enzyme preparation converted L-arginine to an activator, presumably being nitric oxide. These findings were quite rapidly followed by a number of publications identifying endogenous production of nitric oxide that is catalyzed by a family of NO-synthases, which use arginine as a substrate (early reviews on the subject are still quite comprehensive; Forstermann et al. 1991; Moncada and Higgs 1991; Bredt and Snyder 1992; Stuehr and Griffith 1992).

Thus, it took about 15 years to understand why calcium and acetylcholine increase the production of cGMP. At present, this signaling pathway is considered quite established and it is described in all textbooks on vascular pharmacology. A rather simplified and schematic understanding is that acetylcholine binds to muscarinic receptors on endothelial cells and this elevates the intracellular calcium concentration, which leads to activation of nitric oxide synthesis due to calmodulin dependency of NO-synthase in endothelial cells. NO then diffuses into smooth muscle cells and activates soluble guanylyl cyclase increasing the level of cGMP causing smooth muscle relaxation. The relaxation mechanism might involve decreased levels of cytosolic calcium in smooth muscle and decreased phosphorylation of myosin light chain kinase caused by cGMP (Murad 1986, 1998, 2006) and this in turn might be influenced via modulation of myosin light chain phosphatase in case of cGMP-induced calcium desensitization (Khromov et al. 2006).

In parallel to these exciting discoveries, the enzymology of soluble guanylyl cyclase was studied and the structure of the enzyme was determined due to combined efforts of various research teams. Again, the reader is referred to a number of excellent detailed reviews on these subjects (for example see Lucas et al. 2000). Critical findings include enzyme purification from a number of laboratories and demonstration of its heterodimeric nature (Kamisaki et al. 1986) and the presence of a prosthetic heme moiety, which is required for stimulation by nitric oxide (Gerzer et al. 1981; Ignarro et al. 1982a).

Of special note is the activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase by protoporphyrin IX (Ignarro et al. 1982b) suggesting that the enzyme can be stimulated by replacement of the heme. This concept was further advanced by development of two highly potent synthetic activators of heme-deficient or oxidized enzyme, BAY58-2667 (Stasch et al. 2002) and HM1766 (Schindler et al. 2006), and by studies on vasorelaxant and cGMP-elevating effects of delta-aminolevulinic acid, a natural heme precursor (Mingone et al. 2006).

Cloning and deduced primary structures of the beta subunit of the enzyme were reported (Koesling et al. 1988; Nakane et al. 1988) soon followed by the primary structure of the alpha1 subunit (Koesling et al. 1990; Nakane et al. 1990) and alpha2 subunit (Harteneck et al. 1991) and more recent reports on genomic organization of alpha1 and beta1 subunits of the enzyme (Sharina et al. 2000) and promoter regulation for the alpha and beta subunits (Sharina et al. 2003). However, the exact mechanism of activation of the enzyme by nitric oxide and determination of the X-ray structure of the protein are still a matter of research efforts by many investigators.

4 History of Particulate Guanylyl Cyclases

Again, the readers are referred to comprehensive historical and mechanistic reviews of this subject (e.g. Schulz et al. 1989; Lucas et al. 2000; regarding retinal enzymes see Pugh et al. 1997). The situation in this case was similar to the soluble isoform. It was known that particulate enzymes are regulatory; however, their activators were not identified in the early 70s.

First report on specific stimulation of particulate guanylyl cyclase showed stimulation of enzyme activity in the intestinal tissue by stable toxin of Escherichia coli (Hughes et al. 1978). Only 14 years later, the endogenous peptides guanylin and uroguanylin were isolated and demonstrated to be the activator of particulate guanylyl cyclase type C (Currie et al. 1992; Hamra et al. 1993) soon after the primary structure of the enzyme was determined and its functional role as a stable toxin receptor was confirmed (Schulz et al. 1990). Later, this was re-confirmed in knockout mice (Mann et al. 1997).

In case of other particulate guanylyl cyclases, great progress was achieved mostly due to studies of sea urchin spermatozoa, where a number of peptides were identified as stimulators of enzyme activity (for example, see Hansbrough and Garbers 1981). At the same time, peptides of somewhat similar structure were identified as natriuretic factors in atrial myocardial extracts (atrial natriuretic peptides; de Bold et al. 1981). These peptides were shown to be endogenous activators of particulate guanylyl cyclase in various tissues (Hamet et al. 1984; Waldman et al. 1984; Winquist et al. 1984). Later on, co-purification (Kuno et al. 1986; Paul et al. 1987), molecular cloning, sequencing, and expression of recombinant protein indicated that natriuretic peptide receptor is guanylyl cyclase type A (Singh et al. 1988; Chinkers et al. 1989; Lowe et al. 1989; Thorpe and Garbers 1989). The presence (Leitman et al. 1986a, b) and structure of the clearance receptor, which lacks the guanylyl cyclase domain and includes only natriuretic factor-binding region, was also determined (Fuller et al. 1988). The emerging new family of hormonal messengers was complemented by discovery of two other molecules, C-type natriuretic peptide (Furuya et al. 1990) stimulating guanylyl cyclase type B (Koller et al. 1991) and brain natriuretic peptide (Song et al. 1988; Sudoh et al. 1988).

In retina, cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase (Pannbacker et al. 1972) and guanylyl cyclase (Pannbacker 1973) were described for the first time in the early 70s but the role of cGMP in regulation of photoreceptor signal transduction was controversial for a long time. The enzyme in retina does not appear to be regulated by extracellular mediators unlike other known guanylyl cyclases but is modulated by intracellular messengers and proteins. Some researchers argued that calcium ions play the critical role in phototransduction whereas others insisted that cGMP is more important (reviewed in Pugh et al. 1997). Eventually, it was demonstrated that ion channels of the frog outer segments are regulated by cGMP and not by calcium (Fesenko et al. 1985) and the argument was essentially concluded after a report on submicromolar calcium regulation of rod guanylyl cyclase activity (Pepe et al. 1986). The study was further expanded in 1988 (Koch and Stryer 1988) and it became apparent that calcium-dependent regulation of guanylyl cyclase and light-dependent regulation of cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase are tightly coupled during the course of phototransduction.

The search for the activators of particulate guanylyl cyclases is not yet over since there are two so-called orphan transmembrane enzymes with unknown activators, guanylyl cyclases types D and G. Recent encouraging progress had been made with identification of guanylin and/or uroguanylin as regulators of guanylyl cyclase type D, thus contributing to chemosensory function in olfactory epithelium (Leinders-Zufall et al. 2007) while regulation of the enzyme by intracellular calcium and calcium-binding proteins is also important for odorant signal transduction (Duda and Sharma 2008).

Interestingly, cloning studies with the alpha and beta subunits of soluble guanylyl cyclase, the particulate isoforms, and adenylyl cyclase have revealed considerable homology in the catalytic domains of all of these enzymes. Upon activation, soluble guanylyl cyclase can synthesize cGMP and cAMP (Mittal and Murad 1977; Mittal et al. 1979). Mutation of a few amino acids in the catalytic domain can also change the nucleotide substrate specificity to make either cyclic nucleotide (Sunahara et al. 1998). Presumably, the catalytic region of adenylyl and guanylyl cyclases originated from a common ancestral gene that fused with various regulatory domains and thus diverged in evolution (Beuve 1999; Kasahara et al. 2001).

5 History of cGMP-Dependent Protein Kinases (PKG)

Appreciation of cGMP as an intracellular second messenger was followed by search for a cGMP-dependent kinase similar to what had been discovered in case of cAMP. Surveying various tissues and species, Kuo and Greengand found that partially purified protein kinase from lobster tail was activated by cAMP and also by cGMP in a histone phosphorylation assay (Kuo and Greengard 1969). In other tissues, stimulation by cAMP was more effective. In a follow-up study they were able to chromatographically separate these two activities and provided a clear evidence for a separate cGMP-regulated protein kinase (Kuo and Greengard 1970), which is weakly activated by cAMP.

5.1 Purification and Structure of cGMP-Dependent Protein Kinase

Following this discovery, the presence of cGMP-dependent protein kinase activity was demonstrated in various tissues (Hofmann and Sold 1972; Sold and Hofmann 1974) and a number of scientists tried to purify PKG (for example Kuo and Greengard 1974; Nakazawa and Sano 1975). In 1976, Gill and coworkers used an immobilized cGMP analog to affinity capture the cGMP-dependent kinase, which was eluted by cGMP to obtain a homogeneous preparation (Gill et al. 1976). Purified enzyme was a homodimer (Lincoln et al. 1977). In subsequent studies, the affinity purification procedure was modified to use a more accessible cAMP-affinity capture (Glass and Krebs 1979) which provided for a lower level of contamination with cAMP-dependent kinases. Interestingly, the early assays for cGMP were based on radioimmunoassay and the method was similar to previous development of a radioimmunoassay for cAMP. Following the report on cGMP-dependent protein kinase (Kuo and Greengard 1970), lobster muscle extract was utilized for a cGMP binding assay (Murad and Gilman 1971; Murad et al. 1971).

Once the purification procedure was established, several groups focused on determining the primary structure of the enzyme. Amino acid composition of PKG and PKA preparations is similar suggesting a high degree of homology of these two enzymes (Lincoln and Corbin 1977). First peptide sequence of the ATP-binding site of bovine cGMP-dependent kinase was reported in 1982 (Hashimoto et al. 1982). Shortly after that, primary sequence of a peptide from the “hinge” domain and its autophosphorylation site were sequenced (Takio et al. 1983). In 1984, Titani and coworkers finally obtained sufficient quantities of the enzyme to generate overlapping peptide fragments and identified the first full length sequence of PKG (Takio et al. 1984) confirming high degree of similarity with cAMP-dependent protein kinase.

5.2 Discovering the Diversity of PKG Isoforms

Investigating the PKG enzyme from bovine aorta smooth muscle, Wolfe and coworkers noticed two chromatographically close but distinct peaks (Wolfe et al. 1987, 1989). One of these peaks was identical to previously described enzyme purified from bovine lung and was designated as type Iα. The second peak contained a protein with a different N-terminal segment and was designated as type Iβ. Since the difference was only at the N-terminus, it was suggested that these types might result from splicing and are not the products of different genes. In 1989, Wernet from the Hofmann group screened a cDNA library form bovine trachea smooth muscle and isolated two independent cDNAs encoding for the type Iα and Iβ isoforms of cGMP-dependent kinase (Wernet et al. 1989). These cDNAs apparently arise from the same gene through alternative splicing.

Several years earlier, while investigating the distribution of cGMP-dependent protein kinase activity in the intestinal tissue, de Jonge found a membrane-associated activity in the brush border of rat and pig intestine (de Jonge 1981). This activity was biochemically distinct from already well-characterized PKG activity of the enzyme purified from the lung. It associated with the membrane and had a different molecular size (86 vs 74 kDa monomer). This suggested that a novel isoform of cGMP-dependent kinase exists in intestinal tissue. Investigating PKG genes in Drosophila, Kalderon and Rubin found a proof that two independent genes encode for different homologous PKG proteins (Kalderon and Rubin 1989). Inspired by these findings, Uhler screened the cDNA library form mouse brain and found two different types of cDNA. One encoded for the type I enzyme, while another encoded for a novel cGMP-dependent kinase (Uhler 1993) designated as type II. Walter and colleagues screened a cDNA library from rat intestine and found a cDNA for type II enzyme confirming that the membrane-associated PKG discovered in the intestinal brush border is indeed an independent isoform (Jarchau et al. 1994). Although, originally described as a monomer of 86 kDa (de Jonge 1981), type II cGMP-dependent kinase was later shown to be a dimer (Gamm et al. 1995) similar to type I enzyme.

6 Conclusion

The characterization of the proteins functioning in cyclic nucleotide synthesis, hydrolysis, and downstream physiological effects, particularly cGMP, revealed these proteins as important macromolecular targets for drug discovery and development. Many novel drugs have been and will be developed for therapies of a host of important disorders which might explain the growing popularity of this field. The pharmacological applications of these discoveries drive this whole field of research forward at a considerable speed already for over 40 years and will continue to inspire the scientists to contribute more exciting discoveries to improve our understanding of biological processes associated with cGMP.

References

- Arnold WP, Mittal CK, Katsuki S, Murad F. Nitric oxide activates guanylate cyclase and increases guanosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate levels in various tissue preparations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:3203–3207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashman DF, Lipton R, Melicow MM, Price TD. Isolation of adenosine 3′, 5′-mono-phosphate and guanosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate from rat urine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1963;11:330–334. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(63)90566-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beavo JA, Hardman JG, Sutherland EW. Hydrolysis of cyclic guanosine and adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphates by rat and bovine tissues. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:5649–5655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuve A. Conversion of a guanylyl cyclase to an adenylyl cyclase. Methods. 1999;19:545–550. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohme E, Munske K, Schultz G. Formation of cyclic guanosine-3′, 5′-monophosphate in various rat tissues. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmakol. 1969;264:220–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredt DS, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide, a novel neuronal messenger. Neuron. 1992;8:3–11. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90104-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadus AE, Hardman JG, Kaminsky NI, Ball JH, Sutherland EW, Liddle GW. Extracellular cyclic nucleotides. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1971;185:50–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1971.tb45235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker G, Thomas LJ, Jr, Appleman MM. The assay of adenosine 3′, 5′-cyclic monophosphate and guanosine 3′, 5′-cyclic monophosphate in biological materials by enzymatic radioisotopic displacement. Biochemistry. 1968;7:4177–4181. doi: 10.1021/bi00852a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung WY. Cyclic 3′, 5′-nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Effect of divalent cations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;242:395–409. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(71)90231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinkers M, Garbers DL, Chang MS, Lowe DG, Chin HM, Goeddel DV, Schulz S. A membrane form of guanylate cyclase is an atrial natriuretic peptide receptor. Nature. 1989;338:78–83. doi: 10.1038/338078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie MG, Fok KF, Kato J, Moore RJ, Hamra FK, Duffin KL, Smith CE. Guanylin: an endogenous activator of intestinal guanylate cyclase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:947–951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.3.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bold AJ, Borenstein HB, Veress AT, Sonnenberg H. A rapid and potent natriuretic response to intravenous injection of atrial myocardial extract in rats. Life Sci. 1981;28:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deguchi T, Yoshioka M. L-Arginine identified as an endogenous activator for soluble guanylate cyclase from neuroblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:10147–10151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge HR. Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase in intestinal brushborders. Adv Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 1981;14:315–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond GI, Perrott-Yee S. Enzymatic hydrolysis of adenosine 3′, 5′-phosphoric acid. J Biol Chem. 1961;236:1126–1129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda T, Sharma RK. ONE-GC membrane guanylate cyclase, a trimodal odorant signal transducer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;367:440–445. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fesenko EE, Kolesnikov SS, Lyubarsky AL. Induction by cyclic GMP of cationic conductance in plasma membrane of retinal rod outer segment. Nature. 1985;313:310–313. doi: 10.1038/313310a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstermann U, Schmidt HH, Pollock JS, Sheng H, Mitchell JA, Warner TD, Nakane M, Murad F. Isoforms of nitric oxide synthase. Characterization and purification from different cell types. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;42:1849–1857. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90581-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller F, Porter JG, Arfsten AE, Miller J, Schilling JW, Scarborough RM, Lewicki JA, Schenk DB. Atrial natriuretic peptide clearance receptor. Complete sequence and functional expression of cDNA clones. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:9395–9401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furchgott RF, Zawadzki JV. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature. 1980;288:373–376. doi: 10.1038/288373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya M, Takehisa M, Minamitake Y, Kitajima Y, Hayashi Y, Ohnuma N, Ishihara T, Minamino N, Kangawa K, Matsuo H. Novel natriuretic peptide, CNP, potently stimulates cyclic GMP production in rat cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;170:201–208. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91260-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamm DM, Francis SH, Angelotti TP, Corbin JD, Uhler MD. The type II isoform of cGMP-dependent protein kinase is dimeric and possesses regulatory and catalytic properties distinct from the type I isoforms. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27380–27388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George WJ, Polson JB, O’Toole AG, Goldberg ND. Elevation of guanosine 3′, 5′-cyclic phosphate in rat heart after perfusion with acetylcholine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1970;66:398–403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.66.2.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerzer R, Bohme E, Hofmann F, Schultz G. Soluble guanylate cyclase purified from bovine lung contains heme and copper. FEBS Lett. 1981;132:71–74. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80429-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill GN, Holdy KE, Walton GM, Kanstein CB. Purification and characterization of 3′:5′-cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:3918–3922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.3918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass DB, Krebs EG. Comparison of the substrate specificity of adenosine 3′:5′-monophosphate- and guanosine 3′:5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinases. Kinetic studies using synthetic peptides corresponding to phosphorylation sites in histone H2B. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:9728–9738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goridis C, Morgan IG. Guanyl cyclase in rat brain subcellular fractions. FEBS Lett. 1973;34:71–73. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(73)80705-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamet P, Tremblay J, Pang SC, Garcia R, Thibault G, Gutkowska J, Cantin M, Genest J. Effect of native and synthetic atrial natriuretic factor on cyclic GMP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;123:515–527. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)90260-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamra FK, Forte LR, Eber SL, Pidhorodeckyj NV, Krause WJ, Freeman RH, Chin DT, Tompkins JA, Fok KF, Smith CE, et al. Uroguanylin: structure and activity of a second endogenous peptide that stimulates intestinal guanylate cyclase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10464–10468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansbrough JR, Garbers DL. Speract. Purification and characterization of a peptide associated with eggs that activates spermatozoa. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:1447–1452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardman JG, Sutherland EW. Guanyl cyclase, an enzyme catalyzing the formation of guanosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate from guanosine triphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:6363–6370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardman JG, Davis JW, Sutherland EW. Measurement of guanosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate and other cyclic nucleotides. Variations in urinary excretion with hormonal state of the rat. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:4812–4815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harteneck C, Wedel B, Koesling D, Malkewitz J, Bohme E, Schultz G. Molecular cloning and expression of a new alpha-subunit of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Interchangeability of the alpha-subunits of the enzyme. FEBS Lett. 1991;292:217–222. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80871-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto E, Takio K, Krebs EG. Amino acid sequence at the ATP-binding site of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:727–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann F, Sold G. A protein kinase activity from rat cerebellum stimulated by guanosine-3′:5′-monophosphate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;49:1100–1107. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(72)90326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JM, Murad F, Chang B, Guerrant RL. Role of cyclic GMP in the action of heat-stable enterotoxin of Escherichia coli. Nature. 1978;271:755–756. doi: 10.1038/271755a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignarro LJ. Endothelium-derived nitric oxide: actions and properties. FASEB J. 1989;3:31–36. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.1.2642868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignarro LJ, Degnan JN, Baricos WH, Kadowitz PJ, Wolin MS. Activation of purified guanylate cyclase by nitric oxide requires heme. Comparison of heme-deficient, heme-reconstituted and heme-containing forms of soluble enzyme from bovine lung. Biochim Bio-phys Acta. 1982a;718:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(82)90008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignarro LJ, Wood KS, Wolin MS. Activation of purified soluble guanylate cyclase by protoporphyrin IX. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982b;79:2870–2873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.9.2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarchau T, Hausler C, Markert T, Pohler D, Vanderkerckhove J, De Jonge HR, Lohmann SM, Walter U. Cloning, expression, and in situ localization of rat intestinal cGMP-dependent protein kinase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9426–9430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi S, Yamazaki R, Teshima Y. Cyclic 3′, 5′-nucleotide phosphodiesterase, IV. Two enzymes with different properties from brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1971;42:968–974. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(71)90525-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalderon D, Rubin GM. cGMP-dependent protein kinase genes in Drosophila. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:10738–10748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminsky NI, Broadus AE, Hardman JG, Jones DJ, Jr, Ball JH, Sutherland EW, Liddle GW. Effects of parathyroid hormone on plasma and urinary adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate in man. J Clin Invest. 1970;49:2387–2395. doi: 10.1172/JCI106458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamisaki Y, Saheki S, Nakane M, Palmieri JA, Kuno T, Chang BY, Waldman SA, Murad F. Soluble guanylate cyclase from rat lung exists as a heterodimer. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:7236–7241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara M, Unno T, Yashiro K, Ohmori M. CyaG, a novel cyanobacterial adenylyl cyclase and a possible ancestor of mammalian guanylyl cyclases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10564–10569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuki S, Arnold W, Mittal C, Murad F. Stimulation of guanylate cyclase by sodium nitroprusside, nitroglycerin and nitric oxide in various tissue preparations and comparison to the effects of sodium azide and hydroxylamine. J Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 1977;3:23–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khromov AS, Wang H, Choudhury N, McDuffie M, Herring BP, Nakamoto R, Owens GK, Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Smooth muscle of telokin-deficient mice exhibits increased sensitivity to Ca2+ and decreased cGMP-induced relaxation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2440–2445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508566103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Murad F. Evidence for two different forms of guanylate cyclase in rat heart. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:6910–6916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Murad F. Increased particulate and decreased soluble guanylate cyclase activity in regenerating liver, fetal liver, and hepatoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975a;72:1965–1969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Murad F. Two forms of guanylate cyclase in mammalian tissues and possible mechanisms for their regulation. Metabolism. 1975b;24:439–445. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(75)90123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Thomas E, Murad F. Effects of decapitation, ether and pentobarbital on guanosine 3′, 5′-phosphate and adenosine 3′, 5′-phosphate levels in rat tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;343:519–528. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(74)90269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Mittal CK, Murad F. Activation of guanylate cyclase from rat liver and other tissues by sodium azide. J Biol Chem. 1975a;250:8016–8022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Mittal CK, Murad F. Increases in cyclic GMP levels in brain and liver with sodium azide an activator of guanylate cyclase. Nature. 1975b;257:700–702. doi: 10.1038/257700a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch KW, Stryer L. Highly cooperative feedback control of retinal rod guanylate cyclase by calcium ions. Nature. 1988;334:64–66. doi: 10.1038/334064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koesling D, Herz J, Gausepohl H, Niroomand F, Hinsch KD, Mulsch A, Bohme E, Schultz G, Frank R. The primary structure of the 70 kDa subunit of bovine soluble guanylate cyclase. FEBS Lett. 1988;239:29–34. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koesling D, Harteneck C, Humbert P, Bosserhoff A, Frank R, Schultz G, Bohme E. The primary structure of the larger subunit of soluble guanylyl cyclase from bovine lung. Homology between the two subunits of the enzyme. FEBS Lett. 1990;266:128–132. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81523-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller KJ, Lowe DG, Bennett GL, Minamino N, Kangawa K, Matsuo H, Goeddel DV. Selective activation of the B natriuretic peptide receptor by C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) Science. 1991;252:120–123. doi: 10.1126/science.1672777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuno T, Andresen JW, Kamisaki Y, Waldman SA, Chang LY, Saheki S, Leitman DC, Nakane M, Murad F. Co-purification of an atrial natriuretic factor receptor and particulate guanylate cyclase from rat lung. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:5817–5823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo JF, Greengard P. Cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases. IV. Widespread occurrence of adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase in various tissues and phyla of the animal kingdom. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1969;64:1349–1355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.64.4.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo JF, Greengard P. Cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases. VI. Isolation and partial purification of a protein kinase activated by guanosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:2493–2498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo JF, Greengard P. Purification and characterization of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinases. Methods Enzymol. 1974;38:329–350. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(74)38050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama Y, Koyama J, Egami F. Digestion of chemically synthesized polyguanylic acids by ribonuclease T1 and spleen phosphodiesterase. Seikagaku. 1964;36:135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Leinders-Zufall T, Cockerham RE, Michalakis S, Biel M, Garbers DL, Reed RR, Zufall F, Munger SD. Contribution of the receptor guanylyl cyclase GC-D to chemosensory function in the olfactory epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14507–14512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704965104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitman DC, Andresen JW, Kuno T, Kamisaki Y, Chang JK, Murad F. Identification of multiple binding sites for atrial natriuretic factor by affinity cross-linking in cultured endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1986a;261:11650–11655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitman DC, Andresen JW, Kuno T, Kamisaki Y, Chang JK, Murad F. Identification of two binding sites for atrial natriuretic factor in endothelial cells: evidence for a receptor subtype coupled to guanylate cyclase. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1986b;99:103–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln TM, Corbin JD. Adenosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate- and guanosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinases: possible homologous proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:3239–3243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln TM, Dills WL, Jr, Corbin JD. Purification and subunit composition of guanosine 3′:5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase from bovine lung. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:4269–4275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe DG, Chang MS, Hellmiss R, Chen E, Singh S, Garbers DL, Goeddel DV. Human atrial natriuretic peptide receptor defines a new paradigm for second messenger signal transduction. EMBO J. 1989;8:1377–1384. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas KA, Pitari GM, Kazerounian S, Ruiz-Stewart I, Park J, Schulz S, Chepenik KP, Waldman SA. Guanylyl cyclases and signaling by cyclic GMP. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:375–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann EA, Jump ML, Wu J, Yee E, Giannella RA. Mice lacking the guanylyl cyclase C receptor are resistant to STa-induced intestinal secretion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;239:463–466. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingone CJ, Gupte SA, Chow JL, Ahmad M, Abraham NG, Wolin MS. Protoporphyrin IX generation from delta-aminolevulinic acid elicits pulmonary artery relaxation and soluble guanylate cyclase activation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L337–L344. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00482.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal CK, Murad F. Formation of adenosine 3′:5′-monophosphate by preparations of guanylate cyclase from rat liver and other tissues. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:3136–3140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal CK, Braughler JM, Ichihara K, Murad F. Synthesis of adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate by guanylate cyclase, a new pathway for its formation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;585:333–342. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(79)90078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada S. The first Robert Furchgott lecture: from endothelium-dependent relaxation to the l-arginine:NO pathway. Blood Vessels. 1990;27:208–217. doi: 10.1159/000158812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada S, Higgs EA. Endogenous nitric oxide: physiology, pathology and clinical relevance. Eur J Clin Invest. 1991;21:361–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1991.tb01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murad F. Cyclic guanosine monophosphate as a mediator of vasodilation. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:1–5. doi: 10.1172/JCI112536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murad F. Nitric oxide signaling: would you believe that a simple free radical could be a second messenger, autacoid, paracrine substance, neurotransmitter, and hormone? Recent Prog Horm Res. 1998;53:43–59. discussion 59–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murad F. Discovery of some of the biological effects of nitric oxide and its role in cell signaling. Biosci Rep. 1999;19:133–154. doi: 10.1023/a:1020265417394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murad F. Shattuck lecture. Nitric oxide and cyclic GMP in cell signaling and drug development. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2003–2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa063904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murad F, Gilman AG. Adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate and guanosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate: a simultaneous protein binding assay. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;252:397–400. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(71)90020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murad F, Manganiello V, Vaughan M. Effects of guanosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate on glycerol production and accumulation of adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate by fat cells. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:3352–3360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murad F, Manganiello V, Vaughan M. A simple, sensitive protein-binding assay for guanosine 3′:5′-monophosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971;68:736–739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murad F, Mittal CK, Arnold WP, Katsuki S, Kimura H. Guanylate cyclase: activation by azide, nitro compounds, nitric oxide, and hydroxyl radical and inhibition by hemoglobin and myoglobin. Adv Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 1978;9:145–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair KG. Purification and properties of 3′, 5′-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase from dog heart. Biochemistry. 1966;5:150–157. doi: 10.1021/bi00865a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakane M, Saheki S, Kuno T, Ishii K, Murad F. Molecular cloning of a cDNA coding for 70 kilodalton subunit of soluble guanylate cyclase from rat lung. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;157:1139–1147. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80992-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakane M, Arai K, Saheki S, Kuno T, Buechler W, Murad F. Molecular cloning and expression of cDNAs coding for soluble guanylate cyclase from rat lung. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16841–16845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa K, Sano M. Partial purification and properties of guanosine 3′:5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase from pig lung. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:7415–7419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannbacker RG. Control of guanylate cyclase activity in the rod outer segment. Science. 1973;182:1138–1140. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4117.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannbacker RG, Fleischman DE, Reed DW. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase: high activity in a mammalian photoreceptor. Science. 1972;175:757–758. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4023.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul AK, Marala RB, Jaiswal RK, Sharma RK. Coexistence of guanylate cyclase and atrial natriuretic factor receptor in a 180-kD protein. Science. 1987;235:1224–1226. doi: 10.1126/science.2881352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe IM, Panfoli I, Cugnoli C. Guanylate cyclase in rod outer segments of the toad retina. Effect of light and Ca2+ FEBS Lett. 1986;203:73–76. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81439-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price TD, Ashman DF, Melicow MM. Organophosphates of urine, including adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate and guanosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1967;138:452–465. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(67)90542-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh EN, Jr, Duda T, Sitaramayya A, Sharma RK. Photoreceptor guanylate cyclases: a review. Biosci Rep. 1997;17:429–473. doi: 10.1023/a:1027365520442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall TW, Sutherland EW. Formation of a cyclic adenine ribonucleotide by tissue particles. J Biol Chem. 1958;232:1065–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport RM, Murad F. Agonist-induced endothelium-dependent relaxation in rat thoracic aorta may be mediated through cGMP. Circ Res. 1983;52:352–357. doi: 10.1161/01.res.52.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport RM, Draznin MB, Murad F. Endothelium-dependent relaxation in rat aorta may be mediated through cyclic GMP-dependent protein phosphorylation. Nature. 1983;306:174–176. doi: 10.1038/306174a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sager G. Cyclic GMP transporters. Neurochem Int. 2004;45:865–873. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler U, Strobel H, Schonafinger K, Linz W, Lohn M, Martorana PA, Rutten H, Schindler PW, Busch AE, Sohn M, Topfer A, Pistorius A, Jannek C, Mulsch A. Biochemistry and pharmacology of novel anthranilic acid derivatives activating heme-oxidized soluble guanylyl cyclase. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1260–1268. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.018747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz G, Bohme E, Munske K. Guanyl cyclase. Determination of enzyme activity. Life Sci. 1969;8:1323–1332. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(69)90189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz G, Hardman JG, Schultz K, Baird CE, Sutherland EW. The importance of calcium ions for the regulation of guanosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphage levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973;70:3889–3893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.12.3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz S, Chinkers M, Garbers DL. The guanylate cyclase/receptor family of proteins. FASEB J. 1989;3:2026–2035. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.9.2568301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz S, Green CK, Yuen PS, Garbers DL. Guanylyl cyclase is a heat-stable enterotoxin receptor. Cell. 1990;63:941–948. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90497-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharina IG, Krumenacker JS, Martin E, Murad F. Genomic organization of alpha1 and beta1 subunits of the mammalian soluble guanylyl cyclase genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10878–10883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190331697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharina IG, Martin E, Thomas A, Uray KL, Murad F. CCAAT-binding factor regulates expression of the beta1 subunit of soluble guanylyl cyclase gene in the BE2 human neuroblastoma cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11523–11528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934338100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Lowe DG, Thorpe DS, Rodriguez H, Kuang WJ, Dangott LJ, Chinkers M, Goeddel DV, Garbers DL. Membrane guanylate cyclase is a cell-surface receptor with homology to protein kinases. Nature. 1988;334:708–712. doi: 10.1038/334708a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Drummond GI, Khorana HG. Cyclic phosphates. IV. Ribonucleoside 3′, 5′-cyclic phosphates. A general method of synthesis and some properties. J Am Chem Soc. 1961;83:698–706. [Google Scholar]

- Sold G, Hofmann F. Evidence for a guanosine-3′:5′-monophosphate-binding protein from rat cerebellum. Eur J Biochem. 1974;44:143–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song DL, Kohse KP, Murad F. Brain natriuretic factor. Augmentation of cellular cyclic GMP, activation of particulate guanylate cyclase and receptor binding. FEBS Lett. 1988;232:125–129. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80400-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasch JP, Schmidt P, Alonso-Alija C, Apeler H, Dembowsky K, Haerter M, Heil M, Minuth T, Perzborn E, Pleiss U, Schramm M, Schroeder W, Schroder H, Stahl E, Steinke W, Wunder F. NO- and haem-independent activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase: molecular basis and cardiovascular implications of a new pharmacological principle. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136:773–783. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuehr DJ, Griffith OW. Mammalian nitric oxide synthases. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1992;65:287–346. doi: 10.1002/9780470123119.ch8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudoh T, Kangawa K, Minamino N, Matsuo H. A new natriuretic peptide in porcine brain. Nature. 1988;332:78–81. doi: 10.1038/332078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunahara RK, Beuve A, Tesmer JJ, Sprang SR, Garbers DL, Gilman AG. Exchange of substrate and inhibitor specificities between adenylyl and guanylyl cyclases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16332–16338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland EW, Rall TW. Fractionation and characterization of a cyclic adenine ribonucleotide formed by tissue particles. J Biol Chem. 1958;232:1077–1091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takio K, Smith SB, Walsh KA, Krebs EG, Titani K. Amino acid sequence around a “hinge” region and its “autophosphorylation” site in bovine lung cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:5531–5536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takio K, Wade RD, Smith SB, Krebs EG, Walsh KA, Titani K. Guanosine cyclic 3′, 5′-phosphate dependent protein kinase, a chimeric protein homologous with two separate protein families. Biochemistry. 1984;23:4207–4218. doi: 10.1021/bi00313a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WJ, Appleman MM. Characterization of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases of rat tissues. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:3145–3150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe DS, Garbers DL. The membrane form of guanylate cyclase. Homology with a subunit of the cytoplasmic form of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:6545–6549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhler MD. Cloning and expression of a novel cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase from mouse brain. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13586–13591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldman SA, Rapoport RM, Murad F. Atrial natriuretic factor selectively activates particulate guanylate cyclase and elevates cyclic GMP in rat tissues. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:14332–14334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernet W, Flockerzi V, Hofmann F. The cDNA of the two isoforms of bovine cGMP-dependent protein kinase. FEBS Lett. 1989;251:191–196. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81453-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AA, Aurbach GD. Detection of guanyl cyclase in mammalian tissues. Biochim Bio-phys Acta. 1969;191:686–697. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(69)90362-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winquist RJ, Faison EP, Waldman SA, Schwartz K, Murad F, Rapoport RM. Atrial natriuretic factor elicits an endothelium-independent relaxation and activates particulate guanylate cyclase in vascular smooth muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:7661–7664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.23.7661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe L, Francis SH, Landiss LR, Corbin JD. Interconvertible cGMP-free and cGMP-bound forms of cGMP-dependent protein kinase in mammalian tissues. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:16906–16913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe L, Francis SH, Corbin JD. Properties of a cGMP-dependent monomeric protein kinase from bovine aorta. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4157–4162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yetik-Anacak G, Catravas JD. Nitric oxide and the endothelium: history and impact on cardiovascular disease. Vascul Pharmacol. 2006;45:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]