Abstract

There is only 1 US Food and Drug Administration-approved drug for acute ischemic stroke: tissue plasminogen activator (tPA). Due to a short time window and fear of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), tPA remains underutilized. There is great interest in developing combination drugs to use with tPA to improve the odds of a favorable recovery and to reduce the risk of ICH. Minocycline is a broad spectrum antibiotic that has been found to be a neuroprotective agent in preclinical ischemic stroke models. Minocycline inhibits matrix metalloproteinase-9, a biomarker for ICH associated with tPA use. Minocycline is also an anti-inflammatory agent and inhibits poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase- 1. Minocycline has been safe and well tolerated in the clinical trials conducted to date.

Keywords: acute ischemic stroke, tissue plasminogen activator, minocycline, MMP-9, PARP-1

Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is the only US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug for acute ischemic stroke.1 However, it is used in only 3% to 8.5% of stroke patients, partly due to its brief treatment time window of 3 hours.2 More disturbing is the recent report that 64% of U.S. hospitals did not administer tPA to a Medicare recipient over a 2 year period.3 The European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III trial, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, showed that tPA was safe and effective in the 3- to 4.5-hour time window,4 prompting the American Stroke Association to publish a guideline endorsing its use out to 4.5 hours in carefully selected patients.5

There is also increasing interest and use of intra-arterial mechanical clot removal strategies in ischemic stroke patients. Two devices that mechanically remove clots, have received FDA device approval.6, 7 However, to date, neither device has been shown to improve functional outcome.

Recanalization and Reperfusion

The goal of intravenous (IV) thrombolytics and intra-arterial interventional strategies is reperfusion of brain. Recanalization of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) by itself is not sufficient to guarantee reperfusion.8 Reperfusion, rather than recanalization correlates with improved clinical outcome. 9 The no-reflow phenomenon, initially described by Ames in 1968,10 refers to a blockage of blood perfusion in the microvasculature even after restoration of blood flow in larger arteries. The exact pathophysiology of the no-reflow phenomenon is not completely understood but may involve microvascular plugging with leukocytes.11, 12 endothelial and astrocyte swelling,13 and dysfunction of contractile properties of the pericyte due to oxidative stress. 14

The Concept of the Penumbra

The ischemic penumbra was initially described in babboons by Astrup and colleagues.15 In their experiments, the MCA was occluded, the systemic blood pressure was dropped, and microelectrode recording of extracellular potassium, measurements of blood flow, and evoked potentials were performed in neocortex. The penumbra was defined as the area where the neurons were structurally intact (no release of intracellular potassium) but functionally inactive (no evoked response). A dual threshold was described during ischemia, the threshold for release of potassium (core) being lower than the threshold for complete electrical failure. The core of the infarct refers to that part of the brain tissue that is irretrievably damaged and destined to die, whereas the penumbra has diminished perfusion but the tissue is still salvageable. An approximation of the ischemic penumbra can be imaged by both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) perfusion and by newer computed tomography (CT) perfusion techniques.16–18 These techniques are being used, mostly in clinical trials, to determine if tissue is still salvageable and to indicate whether an intervention should be undertaken.

The Need for New Agents and Approaches

Although tPA is an effective drug for stroke, less than 50% of patients with MCA occlusion (MCAO), recanalize with tPA.19 Therefore, there is interest in developing better fibrinolytic agents and also mechanical approaches to improve recanalization rates. Even if the artery is recanalized with tPA or mechanical clot removal devices, there is concern over the no-reflow phenomenon and in restoring perfusion to the microvasculature. There is also evidence that tPA is neurotoxic because it potentiates signaling by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. 20 Lastly and most importantly, tPA is also associated with a risk of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and this risk is cited in surveys as a major reason why emergency department physicians are reluctant to use it.21

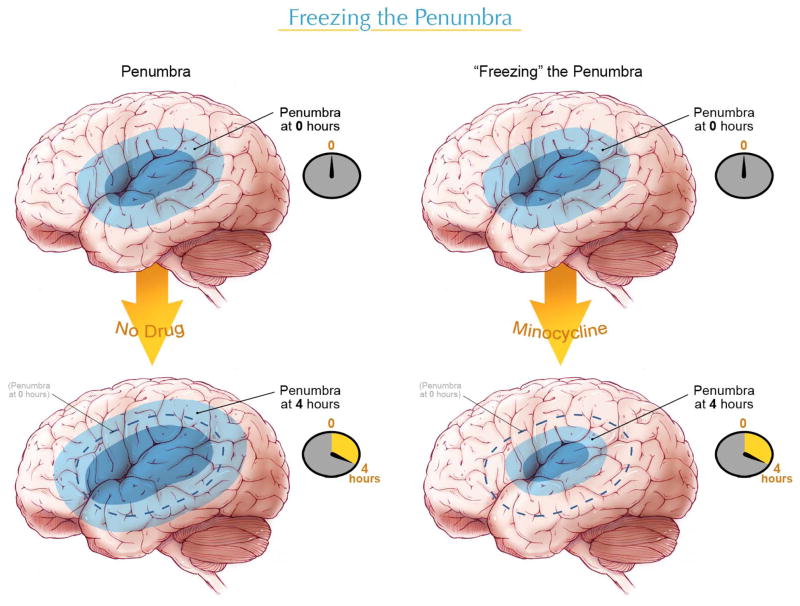

There is an interest in developing drugs or agents to use in combination with tPA. The ideal drug would salvage or “freeze” the penumbra, allowing a longer time window for tPA or other interventional strategies (Figure 1). Another feature of the ideal combination agent would be to reduce the risk of ICH associated with tPA.

Figure 1.

The penumbra is the area of salvageable tissue that is critically time-dependent. Without treatment, the penumbra is likely to convert into core or dead tissue (left). With minocycline or other “neuroprotective” agents, the penumbra can be “frozen” and neurons and tissue salvaged, allowing more time for tPA or an interventional strategy to restore perfusion (right).

Minocycline

Minocycline is a semisynthetic tetracycline that has been in use since the 1970s. Like the tetracyclines, its antibacterial action is related to its inhibition of protein translation by binding to the P30 subunit of the ribosome and preventing entry of aminoacyl transfer RNA into the A site of the ribosome. Its use in acute bacterial infections has diminished due to the development of tigecycline, a glycylcycline with broader antibiotic coverage.22 Minocycline is effective in treating acne 23; beyond its antibacterial effects, minocycline is also an effective anti-inflammatory agent. In a double-blind clinical trial in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, minocycline was found to be safe and effective. 24

Repurposing an Old Drug

There are strong preclinical data that minocycline is effective at reducing infarct size and improving functional outcome in animal stroke models. Initial reports in 1999 showed that minocycline was effective at reducing hippocampal damage in global models of cerebral ischemia and at reducing infarct size in focal ischemia.25, 26 This protective effect was attributed to minocycline’s well-established anti-inflammatory effects. Subsequent studies have borne out this neuroprotective effect. In a clot model of focal cerebral ischemia in the rat, minocycline was shown to reduce infarct size by more than 40% when administered in multiple, large intraperitoneal (IP) doses starting at one hour after clot injection.27, 28 Nagel and colleagues found minocycline to be as effective as hypothermia in a temporary MCAO model.29 Minocycline was also effective at reducing infarct size in a murine transient MCAO model, reduced ICH and ameliorated damage to the blood-brain barrier. 30

Initial studies with minocycline used large IP doses.25, 26 However, IV doses of minocycline in rodents produced faster and more consistent plasma levels of minocycline than IP administration.31 Drug levels after IP administration were erratic and delayed. A key step was to determine whether minocycline would be effective at IV doses that were known to be tolerated in humans (3 mg/kg). 32 Using a rat model of temporary focal cerebral ischemia and determination of infarct size at 24 hours, investigators studied the target concentrations and therapeutic windows associated with neuroprotection. When treatment with minocycline was initiated at either 4 or 5 hours after the onset of ischemia and repeated every 4 hours for 2 more doses, both 3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg demonstrated infarct size reduction out to 5 hours. In animals administered either 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg, neurologic function at 24 hours was significantly improved over saline administration, when treatment was started within 4 hours after MCAO. However, only the 10mg/kg dose improved functional outcome at 5 hours.32 Further studies have confirmed that a doses of 3 mg/kg are neuroprotective in both clot models and longer-duration transient MCAO models. 33, 34

Mechanisms of Action

Minocycline has multiple mechanisms of action. First, it is a potent matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) inhibitor. 35 MMP-9 plays an important role in mediating tissue injury during human ischemic stroke and is associated with intracranial hemorrhage after tPA. Second, minocycline is a potent inhibitor of microglial activation and other inflammatory responses. 30 Third, minocycline inhibits the mitochondrial transition permeability pore. 36–38 Lastly, minocycline is a potent inhibitor of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) at nanomolar concentrations.39 It is possible that the anti-inflammatory effect and anti-microglial effect of minocycline is mediated by the inhibitory effect on PARP-1 as PARP-1 is a coactivator of nuclear factor-κB. 39,40 The available evidence suggests that minocycline’s mechanism of action as a neuroprotective agent may be multifactorial, related to MMP-9 inhibition, PARP inhibition, and other mechanisms. Moreover, minocycline’s inhibition of MMP-9 suggests a vasculoprotective effect.

PARP-1 inhibitors protect the multiple cell types comprising the neurovascular unit (endothelial cells, astrocytes, neurons, and pericytes) and therefore are promising agents for acute ischemic stroke. 41 PARP is an nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-dependent enzyme that catalyses the transfer of adenosine diphosphate (ADP) ribose units from NAD to substrate proteins, thereby contributing to the control of genomic integrity.41, 42 During ischemia, free radical damage to DNA with breaks in the single strand leads to the activation of PARP-1. The transfer of ADP ribose units from NAD leads to intracellular depletion of NAD and adenosine triphosphate, resulting in energy depletion and cell necrosis. Moreover, PAR polymers appear to be toxic and serve as a death signal. 43 PARP activation and PAR polymers cause translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) from mitochondria to the nucleus and activation of a caspase-independent programmed cell death pathway. This PAR polymer-mediated cell death has even led to the coining of a new term, parthanatos (PAR polymers + thanatos [the Greek for death]) to refer to this PAR polymer-mediated release of AIF and caspase independent cell death. 44, 45 PARP inhibitors have also been shown to be effective in rodent models of cerebral ischemia even if started as late as 48 hours after stroke, which is an attractive feature for a stroke drug. 46

However, recent preclinical evidence suggests that only males may benefit from PARP inhibitors in stroke. Male PARP-1 knockout mice have smaller infarcts than male wild-type mice and a PARP-inhibitor, PJ-34 reduces infarct size in male mice; however, PARP I knockout in females leads to larger infarcts and exacerbates ischemic injury.47 As a known PARP-1 inhibitor, minocycline might also be expected to show a differential sex response in cerebral ischemia. In a study comparing minocycline treatment in MCAO in male and female mice, the male mice benefited with reduction of infarct size but there was no reduction in infarct size in mice ovariectomized 1 week before. 48 Unlike the PARP-I inhibitor, PJ-34, minocycline did not enlarge infarct size in female mice; there was just no benefit in females. This may be related to minocycline’s multiple mechanisms of action. One concern in this study is the short duration between ovariectomy and the induction of cerebral ischemia. Estradiol levels may not yet have washed out and may still have had a biologic effect. A possible sex effect of minocycline will need to be closely examined in future human clinical trials.

MMP-9 as a Biomarker for Ischemic Stroke and ICH Risk

MMP-9 plays a role in mediating tissue damage during cerebral ischemia.49–51 In a pathologic study of 5 human stroke patients with hemorrhagic infarction, MMP-9-positive neutrophils were demonstrated infiltrating and surrounding brain microvessels with severe basal lamina type IV collagen degradation and local blood extravasation. 51 MMP-9 was elevated in microvessel endothelium from hemorrhagic and infarcted areas. This study suggests that microvessel and inflammatory MMP-9 responses are associated with hemorrhagic complications after stroke.

Plasma levels of MMP-9 have been shown to be a biomarker for poor outcome, infarct volume, and hemorrhage risk in stroke patients. Plasma MMP-9 levels are associated with hemorrhagic transformation in human stroke52 and increases in plasma MMP-9 are associated with thrombolysis failure in acute stroke. 53 Moreover, baseline plasma MMP-9 is a strong predictor of cerebral infarct volume by DWI imaging.50

Administration of tPA is associated with upregulation of MMP-9.49 There is evidence that this is related to tPA-induced upregulation of the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. 54 Stroke patients treated with tPA have increases in MMP-9 levels and in MMP-9 activity.55, 56 Higher MMP-9 levels after tPA are associated with poor outcome at 3 months.56 Importantly, plasma MMP-9 is associated with tPA-related ICH.57, 58

Minocycline’s Inhibition of Matrix Metalloproteinases

Tetracyclines are known inhibitors of the MMPs.59 Low-dose doxycycline was the first FDA-approved MMP inhibitor and is used in periodontal disease.60 In a rat model of adjuvant arthritis, doxycycline and tetracycline (2 close analogs of minocycline), in combination with standard non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent, reduced joint swelling and inflammation and improved radiological evidence. In this model, the arthritic syndrome was associated with suppression of MMP-2 (gelatinase) activation obtained from the inflamed joints. 61 Minocyline reduced MMP-9 in an experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model. 62 In a collagenase-induced ICH model, minocycline reduced MMP-12 and improved functional outcome. 63 The neuroprotective effect of minocycline in cerebral ischemia is dependent upon MMP-9; minocycline reduces infarct size in wild-type but not in MMP-9 knockout mice.64 Our laboratory showed that minocycline potently inhibits MMP 9 in vitro and in brain at doses of 3 mg/kg.35 In a prospective, randomized placebo-controlled pilot study of submicrobial doses of doxycycline in patients with acute coronary syndrome, pro MMP-9 activity was reduced by 50% in doxycycline-treated patients. 65

Combination of Minocycline and tPA

There is great interest in finding agents that can both extend the therapeutic time window of tPA and reduce the hemorrhage risk with tPA. Murata and colleagues34 reported that minocycline was effective when used in combination with tPA. Using a thromboembolic clot model in male spontaneously hypertensive rats, IV minocycline, 3 mg/kg, was effective alone at 4 hours. When combined with delayed tPA at 6 hours, minocycline reduced infarct size, ameliorated tPA-related ICH, and reduced plasma MMP-9 levels. 34

Minocycline was also effective at reducing tPA-related hemorrhage and blood-brain barrier injury in a mechanical 3-hour temporary occlusion model.33 Minocycline, at a dose of 3 mg/kg given in combination with tPA at the time of reperfusion, reduced tPA-related hemorrhage, reduced brain MMP-9 levels, improved functional outcome and reduced mortality.33 Moreover, minocycline prevented the degradation of brain collagen IV and laminin levels and preserved vascular integrity.

Clinical Trials With Minocycline in Stroke

In a randomized, open-label, placebo-controlled, blinded evaluator clinical trial of oral minocycline within 6 to 24 hours of stroke onset, minocycline significantly improved outcome at 7, 30 and 90 days after stroke.66 In this trial, tPA-treated patients were excluded and the patients had to be able to swallow. Minocycline was administered at a dose of 200 mg/d for 5 days with a mean time of treatment of 12.6 hours after symptom onset. The trial enrolled 152 subjects, 74 randomized to minocycline and 77 to placebo. Although the study results are encouraging, the placebo-treated group had poorer outcomes than in other clinical trials that may partly explain the results.

The Minocycline to Improve Neurologic Outcome (MINO) clinical trial is an open label, dose escalation early phase clinical trial of minocycline in acute ischemic stroke with a 6-hour time window (http://ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00630396). Treatment with tPA is allowed. The modified continual reassessment method was used to facilitate dose finding. The trial has completed enrollment of 60 subjects and follow-up of patients is in progress. Minocycline has been safe and very well tolerated and there have been no serious infusion-related toxicities, even when the full dose of 10 mg/kg (maximum of 700 mg) was administered over 1 hour. The half-life of minocycline is approximately 24 hours, allowing dosing every 24 hours. The next step is a planned phase III trial of minocycline in combination with tPA in acute ischemic stroke.

Conclusions

Minocycline represents a “repurposed drug” for acute ischemic stroke (Table 1). Although initially developed as a broad-spectrum antibiotic, minocycline was tested in animal cerebral ischemia models because of its anti-inflammatory properties and found to be effective. Subsequently, minocycline’s inhibition of MMP-9 has been better appreciated and its inhibition of PARP-1 discovered. It appears to be a safe, well-tolerated agent with a long half-life and is an ideal drug to administer in rural and community hospitals and possibly in pre-hospital settings. Its known inhibition of MMP-9 makes it an attractive drug to use in combination with tPA.

Table 1.

Minocycline as a potential agent to use in combination with tPA

|

Acknowledgments

I wish to acknowledge Michael Jensen of the Medical College of Georgia Department of Medical Illustration for creating figure 1.

This work is supported by NINDS/NIH, NS055728

Footnotes

Disclosures

David C Hess M.D. has served on the Speaker’s Bureau for Genentech and Boehringer Ingelheim and has served as a consultant for Ferrer

References

- 1.Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reeves MJ, Arora S, Broderick JP, et al. Acute stroke care in the US: results from 4 pilot prototypes of the Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry. Stroke. 2005;36:1232–1240. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000165902.18021.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleindorfer D, Xu Y, Moomaw CJ, et al. US geographic distribution of rt-PA utilization by hospital for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:3580–3584. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.554626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317–1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Zoppo GJ, Saver JL, Jauch EC, et al. Expansion of the time window for treatment of acute ischemic stroke with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator: a science advisory from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2009;40:2945–2948. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.192535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith WS, Sung G, Starkman S, et al. Safety and efficacy of mechanical embolectomy in acute ischemic stroke: results of the MERCI trial. Stroke. 2005;36:1432–1438. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000171066.25248.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bose A, Henkes H, Alfke K, et al. The Penumbra System: a mechanical device for the treatment of acute stroke due to thromboembolism. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1409–1413. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soares BP, Chien JD, Wintermark M. MR and CT monitoring of recanalization, reperfusion, and penumbra salvage: everything that recanalizes does not necessarily reperfuse! Stroke. 2009;40:S24–27. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.526814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Silva DA, Fink JN, Christensen S, et al. Assessing reperfusion and recanalization as markers of clinical outcomes after intravenous thrombolysis in the echoplanar imaging thrombolytic evaluation trial (EPITHET) Stroke. 2009;40:2872–2874. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.543595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ames A, 3rd, Wright RL, Kowada M, et al. Cerebral ischemia. II. The no-reflow phenomenon. Am J Pathol. 1968;52:437–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.del Zoppo GJ, Schmid-Schonbein GW, Mori E, et al. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes occlude capillaries following middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion in baboons. Stroke. 1991;22:1276–1283. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.10.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallenbeck JM, Dutka AJ, Tanishima T, et al. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte accumulation in brain regions with low blood flow during the early postischemic period. Stroke. 1986;17:246–253. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia JH, Liu KF, Yoshida Y, et al. Brain microvessels: factors altering their patency after the occlusion of a middle cerebral artery (Wistar rat) Am J Pathol. 1994;145:728–740. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yemisci M, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Vural A, et al. Pericyte contraction induced by oxidative-nitrative stress impairs capillary reflow despite successful opening of an occluded cerebral artery. Nat Med. 2009;15:1031–1037. doi: 10.1038/nm.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Astrup J, Symon L, Branston NM, et al. Cortical evoked potential and extracellular K+ and H+ at critical levels of brain ischemia. Stroke. 1977;8:51–57. doi: 10.1161/01.str.8.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molina CA, Saver JL. Extending reperfusion therapy for acute ischemic stroke: emerging pharmacological, mechanical, and imaging strategies. Stroke. 2005;36:2311–2320. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000182100.65262.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wintermark M, Flanders AE, Velthuis B, et al. Perfusion-CT assessment of infarct core and penumbra: receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in 130 patients suspected of acute hemispheric stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:979–985. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000209238.61459.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muir KW, Buchan A, von Kummer R, et al. Imaging of acute stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:755–768. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70545-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexandrov AV, Molina CA, Grotta JC, et al. Ultrasound-enhanced systemic thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2170–2178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicole O, Docagne F, Ali C, et al. The proteolytic activity of tissue-plasminogen activator enhances NMDA receptor-mediated signaling. Nat Med. 2001;7:59–64. doi: 10.1038/83358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown DL, Barsan WG, Lisabeth LD, et al. Survey of emergency physicians about recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Projan SJ. Preclinical pharmacology of GAR-936, a novel glycylcycline antibacterial agent. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20:219S–223S. doi: 10.1592/phco.20.14.219s.35046. discussion 224S–228S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leyden JJ, McGinley KJ, Kligman AM. Tetracycline and minocycline treatment. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tilley BC, Alarcon GS, Heyse SP, et al. Minocycline in rheumatoid arthritis. A 48-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. MIRA Trial Group. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:81–89. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-2-199501150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yrjanheikki J, Keinanen R, Pellikka M, et al. Tetracyclines inhibit microglial activation and are neuroprotective in global brain ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15769–15774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yrjanheikki J, Tikka T, Keinanen R, et al. A tetracycline derivative, minocycline, reduces inflammation and protects against focal cerebral ischemia with a wide therapeutic window. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13496–13500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang CX, Yang T, Noor R, et al. Delayed minocycline but not delayed mild hypothermia protects against embolic stroke. BMC Neurol. 2002;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang CX, Yang T, Shuaib A. Effects of minocycline alone and in combination with mild hypothermia in embolic stroke. Brain Res. 2003;963:327–329. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagel S, Su Y, Horstmann S, et al. Minocycline and hypothermia for reperfusion injury after focal cerebral ischemia in the rat: effects on BBB breakdown and MMP expression in the acute and subacute phase. Brain Res. 2008;1188:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yenari MA, Xu L, Tang XN, et al. Microglia potentiate damage to blood-brain barrier constituents: improvement by minocycline in vivo and in vitro. Stroke. 2006;37:1087–1093. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000206281.77178.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fagan SC, Edwards DJ, Borlongan CV, et al. Optimal delivery of minocycline to the brain: implication for human studies of acute neuroprotection. Exp Neurol. 2004;186:248–251. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu L, Fagan SC, Waller JL, et al. Low dose intravenous minocycline is neuroprotective after middle cerebral artery occlusion-reperfusion in rats. BMC Neurol. 2004;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Machado LS, Sazonova IY, Kozak A, et al. Minocycline and tissue-type plasminogen activator for stroke: assessment of interaction potential. Stroke. 2009;40:3028–3033. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.556852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murata Y, Rosell A, Scannevin RH, et al. Extension of the thrombolytic time window with minocycline in experimental stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:3372–3377. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.514026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Machado LS, Kozak A, Ergul A, et al. Delayed minocycline inhibits ischemia-activated matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 after experimental stroke. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gieseler A, Schultze AT, Kupsch K, et al. Inhibitory modulation of the mitochondrial permeability transition by minocycline. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:888–896. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haroon MF, Fatima A, Scholer S, et al. Minocycline, a possible neuroprotective agent in Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON): studies of cybrid cells bearing 11,778 mutation. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;28:237–250. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Theruvath TP, Zhong Z, Pediaditakis P, et al. Minocycline and N-methyl-4-isoleucine cyclosporin (NIM811) mitigate storage/reperfusion injury after rat liver transplantation through suppression of the mitochondrial permeability transition. Hepatology. 2008;47:236–246. doi: 10.1002/hep.21912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alano CC, Kauppinen TM, Valls AV, et al. Minocycline inhibits poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 at nanomolar concentrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9685–9690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600554103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petrilli V, Herceg Z, Hassa PO, et al. Noncleavable poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 regulates the inflammation response in mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1072–1081. doi: 10.1172/JCI21854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moroni F, Chiarugi A. Post-ischemic brain damage: targeting PARP-1 within the ischemic neurovascular units as a realistic avenue to stroke treatment. Febs J. 2009;276:36–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moroni F. Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase 1 (PARP-1) and postischemic brain damage. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andrabi SA, Kim NS, Yu SW, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) polymer is a death signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18308–18313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606526103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.David KK, Andrabi SA, Dawson TM, et al. Parthanatos, a messenger of death. Front Biosci. 2009;14:1116–1128. doi: 10.2741/3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Poly(ADP-ribose) signals to mitochondrial AIF: A key event in parthanatos. Exp Neurol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kauppinen TM, Suh SW, Berman AE, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase suppresses inflammation and promotes recovery after ischemic injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:820–829. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCullough LD, Zeng Z, Blizzard KK, et al. Ischemic nitric oxide and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in cerebral ischemia: male toxicity, female protection. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:502–512. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li J, McCullough LD. Sex differences in minocycline-induced neuroprotection after experimental stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:670–674. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sumii T, Lo EH. Involvement of matrix metalloproteinase in thrombolysis-associated hemorrhagic transformation after embolic focal ischemia in rats. Stroke. 2002;33:831–836. doi: 10.1161/hs0302.104542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Montaner J, Rovira A, Molina CA, et al. Plasmatic level of neuroinflammatory markers predict the extent of diffusion-weighted image lesions in hyperacute stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:1403–1407. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000100044.07481.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosell A, Cuadrado E, Ortega-Aznar A, et al. MMP-9-positive neutrophil infiltration is associated to blood-brain barrier breakdown and basal lamina type IV collagen degradation during hemorrhagic transformation after human ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:1121–1126. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.500868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Montaner J, Alvarez-Sabin J, Molina CA, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase expression is related to hemorrhagic transformation after cardioembolic stroke. Stroke. 2001;32:2762–2767. doi: 10.1161/hs1201.99512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heo JH, Kim SH, Lee KY, et al. Increase in plasma matrix metalloproteinase-9 in acute stroke patients with thrombolysis failure. Stroke. 2003;34:e48–50. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000073788.81170.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang X, Lee SR, Arai K, et al. Lipoprotein receptor-mediated induction of matrix metalloproteinase by tissue plasminogen activator. Nat Med. 2003;9:1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/nm926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Horstmann S, Kalb P, Koziol J, et al. Profiles of matrix metalloproteinases, their inhibitors, and laminin in stroke patients: influence of different therapies. Stroke. 2003;34:2165–2170. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000088062.86084.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kelly PJ, Morrow JD, Ning M, et al. Oxidative stress and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in acute ischemic stroke: the Biomarker Evaluation for Antioxidant Therapies in Stroke (BEAT-Stroke) study. Stroke. 2008;39:100–104. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.488189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Montaner J, Molina CA, Monasterio J, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 pretreatment level predicts intracranial hemorrhagic complications after thrombolysis in human stroke. Circulation. 2003;107:598–603. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000046451.38849.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Castellanos M, Sobrino T, Millan M, et al. Serum cellular fibronectin and matrix metalloproteinase-9 as screening biomarkers for the prediction of parenchymal hematoma after thrombolytic therapy in acute ischemic stroke: a multicenter confirmatory study. Stroke. 2007;38:1855–1859. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.481556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rifkin BR, Vernillo AT, Golub LM. Blocking periodontal disease progression by inhibiting tissue-destructive enzymes: a potential therapeutic role for tetracyclines and their chemically-modified analogs. J Periodontol. 1993;64:819–827. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.8s.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ashley RA. Clinical trials of a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor in human periodontal disease. SDD Clinical Research Team. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;878:335–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Greenwald RA. Treatment of destructive arthritic disorders with MMP inhibitors. Potential role of tetracyclines. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;732:181–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb24734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brundula V, Rewcastle NB, Metz LM, et al. Targeting leukocyte MMPs and transmigration: minocycline as a potential therapy for multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2002;125:1297–1308. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Power C, Henry S, Del Bigio MR, et al. Intracerebral hemorrhage induces macrophage activation and matrix metalloproteinases. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:731–742. doi: 10.1002/ana.10553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koistinaho M, Malm TM, Kettunen MI, et al. Minocycline protects against permanent cerebral ischemia in wild type but not in matrix metalloprotease-9-deficient mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:460–467. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brown DL, Desai KK, Vakili BA, et al. Clinical and biochemical results of the metalloproteinase inhibition with subantimicrobial doses of doxycycline to prevent acute coronary syndromes (MIDAS) pilot trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:733–738. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000121571.78696.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lampl Y, Boaz M, Gilad R, et al. Minocycline treatment in acute stroke: an open-label, evaluator-blinded study. Neurology. 2007;69:1404–1410. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000277487.04281.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]