Abstract

The use of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents has led to a dramatic increase in the number of intravitreal injections. Endophthalmitis remains a rare but potentially vision-threatening complication of intravitreal injections. Recent large series have estimated this risk to be about one in 3,000 injections or less. Bevacizumab, which is generally prepared by a compounding pharmacy, is associated with additional risks of contamination. Although endophthalmitis cannot be prevented in all cases, certain risk reduction strategies have been proposed, including the use of an eyelid speculum, povidone iodine, avoidance of needle contact with the eyelid margin or eyelashes, and avoidance of routine post-injection antibiotics. Despite these precautions, some patients will develop endophthalmitis following intravitreal anti-VEGF injections, and outcomes may be poor despite prompt and appropriate therapy.

Keywords: Endophthalmitis, Intravitreal injection, Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), Bevacizumab, Ranibizumab, Ophthalmology

Introduction

The introduction of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents has resulted in a dramatic increase in intravitreal injections over the past 10 years [1]. Perhaps the most serious complication of intravitreal injections is infectious endophthalmitis, which even with prompt and appropriate therapy may lead to severe visual loss and potentially loss of the eye [2].

Endophthalmitis after intravitreal injections is one of several categories of endophthalmitis—including post-surgical, post-traumatic, endogenous and associated with microbial keratitis [3]—and is associated with some unique features. For example, a retrospective series of 101 patients with endophthalmitis (48 following cataract surgery and 53 following intravitreal injection) reported that the cases associated with intravitreal injection were more likely to be caused by Streptococcus species, to present earlier and to have relatively poorer visual outcomes [4]. Recently, there has been increased understanding of these unique features, especially regarding rates of endophthalmitis, specific risks associated with compounded medications, risk reduction strategies and other considerations.

Rates of Endophthalmitis

Most patients undergoing treatment with anti-VEGF agents receive a series of injections potentially over months or years. It is therefore important to distinguish between rates of endophthalmitis per injection versus cumulative rates of endophthalmitis per treated eye over the course of therapy. The per-patient rates represent cumulative risk and will necessarily be higher than the per-injection rates. In either case, the rates are generally very low, but per-patient rates may approach 1 % when viewed over a 2-year course of treatment.

For example, recent large series from Denmark (2 cases out of 7,584 injections, 0.026 %) [5], Australia (2 out of 9,162, 0.022 %) [6], Massachusetts (3 out of 10,208, 0.029 %) [7] and Florida (12 out of 60,322, 0.020 %) [8•] suggest a rate of 1 in 3,000 anti-VEGF injections or less (Table 1). A population-based study in the UK estimated a per-injection rate of 0.025 % [9]. A US single-center review of 10,164 consecutive injections performed using bimanual assisted eyelid retraction (using an assistant’s fingers to manually retract the lids), without a lid speculum, reported 3 cases of endophthalmitis (0.030 %) [10]. Interestingly, a review of the US Medicare claims database reported per-injection rates of 0.09 % for endophthalmitis and 0.11 % for noninfectious uveitis [11].

Table 1.

Selected reports of per-injection rates of endophthalmitis after intravitreal anti-VEGF injections

| Series | Cases | Injections | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rasmussen et al. [5] | 2 | 7,584 | 0.026 |

| Gillies et al. [6] | 2 | 9,162 | 0.022 |

| Englander et al. [7] | 3 | 10,208 | 0.029 |

| Moshfeghi et al. [8•] | 12 | 60,322 | 0.020 |

Rates per patient over multiple years may be substantially higher VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor

In contrast to the per-injection rates, the Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT), a prospective randomized clinical trial (RCT) comparing ranibizumab (Lucentis, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) and bevacizumab (Avastin, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) in 1,107 patients with exudative AMD, reported per-patient rates of endophthalmitis of 0.7 % with ranibizumab and 1.2 % with bevacizumab (p = 0.38) over 2 years [12]. The Randomised Controlled Trial of Alternative Treatments to Inhibit VEGF in Age-Related Choroidal Neovascularization (IVAN), another RCT comparing ranibizumab to bevacizumab, did not specifically report endophthalmitis rates but reported ‘‘severe uveitis’’ in 1 of 610 patients at 1 year (0.16 %) [13].

Compounded Medications

Bevacizumab is used in an ‘‘off-label’’ capacity to treat retinal diseases and is generally prepared by compounding pharmacies for intravitreal use. The use of a compounding pharmacy introduces an additional step between the drug manufacturer and treating physician, and this additional step may result in contamination of the medication (Fig. 1). For example, a series of eight patients treated in a single practice in New York with a combination of compounded bevacizumab and triamcinolone acetonide from a single compounding pharmacy developed fungal endophthalmitis with Bipolaris hawaiiensis [14•]. A series of 12 patients in Florida treated with bevacizumab from a single compounding pharmacy developed endophthalmitis with a common strain of Streptococcus mitis/oralis, and despite prompt treatment only 1 patient regained pre-injection visual acuity [15•] (Table 2).

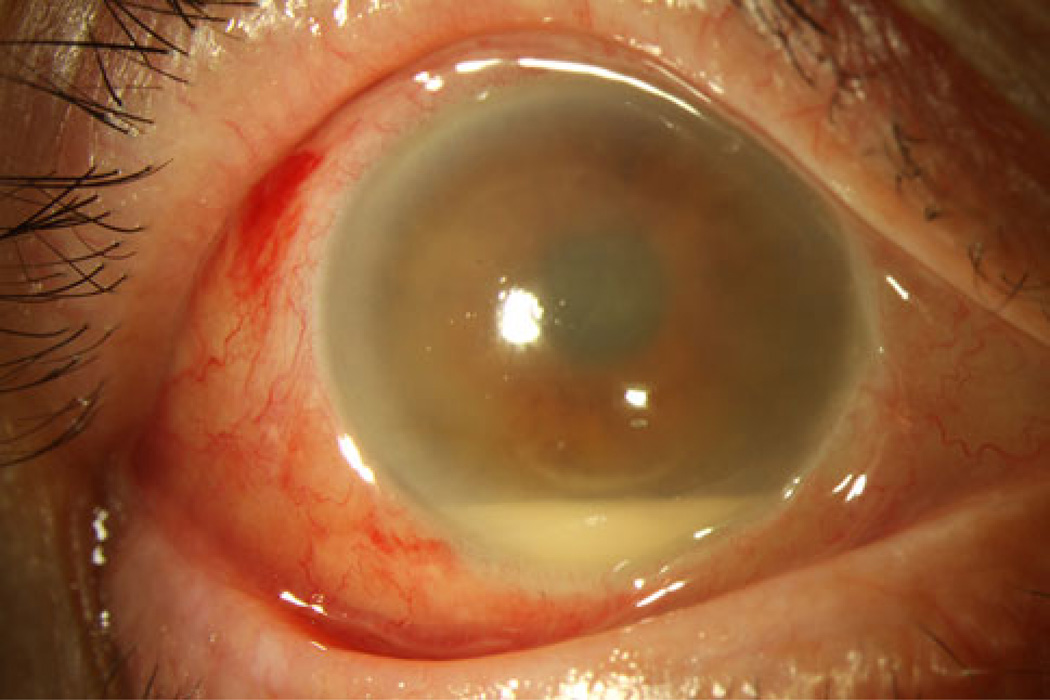

Fig. 1.

Endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection. A 72-year-old white male underwent treatment with bevacizumab and presented 2 days later with hand motion vision, moderate conjunctival injection, hypopyon and fibrin. Vitreous cultures subsequently isolated Streptococcus species

Table 2.

Selected series of endophthalmitis associated with compounded medications

Intravitreal injections also may be associated with sterile intraocular inflammation of unknown causes. Distinguishing between non-infectious versus infectious inflammation after injection may be very difficult. A Japanese group reported culture-negative endophthalmitis in 14 consecutive patients treated with a single batch of bevacizumab [16]. In one center in India, six of eight patients who were treated with bevacizumab from the same vial developed culture-negative endophthalmitis [17]. One center in Iran reported culture-negative intraocular inflammation in 4 out of 15 eyes treated with one batch of bevacizumab and 7 out of 18 eyes (including one bilateral case) from a second batch [18]. A retrospective review of 1,584 injections reported that severe intraocular inflammation was 12 times more common after treatment with bevacizumab than with ranibizumab [19]. Sequential noninfectious intraocular inflammation has been reported in the same patient following treatment with bevacizumab and then ranibizumab, suggesting cross-sensitivity [20].

Counterfeit bevacizumab has been reported in China. Eighty patients out of 116 injected from three vials of counterfeit bevacizumab developed culture-negative endophthalmitis; 21 patients underwent pars plana vitrectomy (PPV), and endotoxin was identified in the vitreous samples [21].

Risk Reduction Strategies

Multiple strategies have been suggested to reduce the risk of post-injection endophthalmitis. At this time, it is not possible to prevent endophthalmitis, and its incidence should not necessarily be interpreted as a failure of surgeon technique [22].

Oral flora may represent a relatively greater risk factor for endophthalmitis following intravitreal injection than for other categories of endophthalmitis. A meta-analysis of 52 endophthalmitis cases out of 105,536 injections (0.049 %) reported that Streptococcus isolates comprised 30.8 % of culture-positive cases, which is significantly greater than that reported in multiple post-surgical endophthalmitis series [23]. A series of 109 cases of endophthalmitis (88 post-surgical and 21 post-injection) reported Streptococcus viridans organisms in 14.3 % of post-injection cases versus 4.5 % of post-surgical cases (p = 0.13) [24].

There are no randomized, prospective trials evaluating the use or non-use of facemasks. In two separate small prospective trials with simulated intravitreal injections, bacterial dispersal was significantly lessened by wearing a face mask or by not speaking [25, 26]. A Japanese series of 15,144 injections performed using a protocol involving the use of surgical masks by the physician and nurse assistant, and a drape on the patient’s face, resulted in zero cases of endophthalmitis [27].

There appears to be a long-term trend away from the routine use of post-injection topical antibiotics. A series in Spain reported a significantly greater per-injection rate of endophthalmitis using ofloxacin (0.12 %) versus azithromycin (0.049 %) [28]. However, many other authors have reported that antibiotic use does not reduce rates of endophthalmitis and may in fact increase the risk. For example, a series from Iran reported that 68 % of 5,901 injected eyes were treated with antibiotics, and 6 endophthalmitis cases (0.10 %) occurred, all in antibiotic-treated eyes [29]. A series of 15,895 injections (including anti-VEGF agents and triamcinolone acetonide) reported higher overall rates of endophthalmitis in patients treated with topical antibiotics than in patients not so treated [30]. The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network reported a series of 8,027 intravitreal injections in which there was a nonsignificantly higher rate of endophthalmitis (0.13 vs. 0.03 %, p = 0.25) with the use of topical antibiotics [31].

The repeated use of topical antibiotics following repeated intravitreal injections may change the conjunctival flora. In a prospective non-randomized study in which 84 patients were treated with topical moxifloxacin after monthly injections and 94 patients were not, the treated patients, but not the untreated patients, demonstrated statistically significant increases in minimal inhibitory concentrations of ocular surface flora, indicating increased resistance to moxifloxacin and ceftazidime [32]. Alternatively, another prospective study of 104 patients reported that repeated exposure to topical fluoroquinolones did not affect baseline fluoroquinolone resistance in conjunctival and nasal flora, although the investigators reported that 45 % of patients harbored at least one fluoroquinolone-resistant organism at baseline [33].

Other variations on the traditional ‘‘prep’’ have been investigated. A single-surgeon series from Australia of 12,249 injections reported a significantly lower endophthalmitis rate when the injection was performed in an operating room, rather than in the clinic [34]. In contrast, a comparison of two groups (one in the US, one in Italy) reported a nonsignificantly higher endophthalmitis rate in an operating room setting compared to a clinic setting (0.065 vs. 0.035 %) [35]. A prospective series of 100 patients randomized them between the use of 1.25 % povidone-iodine plus topical levofloxacin versus the more commonly used 5 % povidone-iodine and found no significant differences with respect to conjunctival flora reduction [36]. In a series of 8,802 injections, the application of 2 % lidocaine gel prior to povidone-iodine did not affect rates of endophthalmitis [37].

Other Considerations

A minority of injections may result in a small amount of liquid reflux back under the conjunctiva, resulting in a temporary bleb. It is unclear whether the fluid in this bleb represents medication or vitreous, but it has been proposed that vitreous reflux may be a risk factor for endophthalmitis [38]. An animal study using radiolabeled anti-VEGF agents demonstrated that this material is most likely the medication itself [39].

The technique of bilateral same-day intravitreal injections has been reported to have a similar safety profile to that of unilateral injections [40], but one center reported two patients who developed bilateral Staphylococcus epidermidis endophthalmitis following this procedure [41].

Unusual organisms recently reported after intravitreal injections include group G Streptococcus [42] and Rhizobium radiobacter [43].

There is no current consensus on the preferred treatment of post-injection endophthalmitis. The Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study did not enroll patients with post-injection endophthalmitis, so its findings cannot be directly applied to these patients. PPV with silicone oil infusion has been reported as a treatment of post-injection endophthalmitis [44], but another group reported more favorable treatment outcomes using vitreous tap and inject rather than PPV in a series of 23 eyes [45].

Conclusions

There is an increasing understanding of the factors influencing post-injection endophthalmitis, and current rates are very low, in the range of 1 in 3,000 injections or less. Nevertheless, the disease still occurs, and it may not be possible to completely prevent it.

Bevacizumab, which is generally prepared by a compounding pharmacy, is associated with additional risks. A root-cause analysis has suggested using a single vial of bevacizumab for each eye, which substantially increases costs, or strictly adhering to US Pharmacopoeia Chapter 797 requirements using one vial for multiple injections [46]. Outside the US, however, adherence to these requirements may be impractical [47].

Certain risk reduction strategies may be beneficial in reducing rates of post-injection endophthalmitis (Table 3). The use of face masks during intravitreal injections may be helpful, although discouraging talking may be similarly helpful. There is no current consensus regarding face masks, and they should not be considered standard practice at this time [48], although there does not appear to be any risk associated with their use. In contrast, it is becoming increasingly apparent that topical antibiotics do not reduce the rate of endophthalmitis following intravitreal anti-VEGF agents and that antisepsis, rather than topical antibiotics, is a preferred practice [49]. In fact, the routine use of topical antibiotics may actually be detrimental by increasing costs and leading to the emergence of multi-drug-resistant organisms [50]. By using these strategies, risks of post-injection endophthalmitis may be reduced, although infections will still occur, occasionally with severe visual consequences.

Table 3.

Strategies to reduce risk of post-injection endophthalmitis

| Povidone-iodine preparation of conjunctiva and eyelid margins |

| Eyelid speculum |

| Avoidance of needle contact with eyelid margins or eyelashes |

| Facemask or reduced talking during procedures (controversial) |

| Avoidance of routine antibiotics (controversial) |

Acknowledgments

Partially supported by NIH Center Core Grant P30EY014801, an Unrestricted Grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, and the Department of Defense (DOD grant #W81XWH-09-1-0675).

Footnotes

Disclosures Dr. Schwartz has served on advisory boards for Alimera, Bausch + Lomb, and Santen, and has received lecture fees from Regeneron and ThromboGenics. Dr. Flynn has served on advisory boards for Santen and has received lecture fees from Vindico.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Stephen G. Schwartz, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, 311 9th Street North, #100, Naples, FL 34102, USA, sschwartz2@med.miami.edu

Harry W. Flynn, Jr., Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, 900 NW 17th Street, Miami, FL 33136, USA

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

- 1.Ramulu PY, Do DV, Corcoran KJ, Corcoran SL, Robin AL. Use of retinal procedures in medicare beneficiaries from 1997 to 2007. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(10):1335–1340. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz SG, Flynn HW, Jr, Scott IU. Endophthalmitis after intra-vitreal injections. ExpertOpin Pharmacother. 2009;10(13):2119–2126. doi: 10.1517/14656560903081752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz SG, Flynn HW, Jr, Scott IU. Endophthalmitis: classification and current management. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2007;2(3):385–396. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simunovic MP, Rush RB, Hunyor AP, Chang AA. Endophthalmitis following intravitreal injection versus endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: clinical features, causative organisms and post-treatment outcomes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(6):862–866. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rasmussen A, Bloch SB, Fuchs J, et al. A 4-year longitudinal study of 555 patients treated with ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(12):2630–2636. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillies MC, Walton R, Simpson JM, et al. Prospective audit of exudative age-related macular degeneration: 12-month outcomes in treatment-naïve eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(8):5754–5760. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-11993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Englander M, Chen TC, Paschalis EI, Miller JW, Kim IK. Intravitreal injections at the Massachusetts eye and ear infirmary: analysis of treatment indications and postinjection endophthalmitis rates. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(4):460–465. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moshfeghi AA, Rosenfeld PJ, Flynn HW, Jr, et al. Endophthalmitis after intravitreal vascular (corrected) endothelial growth factor antagonists: a 6-year experience at a university referral center. Retina. 2011;31(4):662–668. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31821067c4. A case series of endophthalmitis following intravitreal anti-VEGF injections in a very large (60,322) series.

- 9.Lyall DA, Tey A, Foot B, et al. Post-intravitreal anti-VEGF endophthalmitis in the United Kingdom: incidence, features, risk factors, and outcomes. Eye (Lond) 2012;26(12):1517–1526. doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fineman HS, Hsu J, Sprin MJ, Kaiser RS. Bimanual assisted eyelid retraction technique for intravitreal injections. Retina. 2013;33(9):1968–1970. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318287da92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Day S, Acquah K, Mruthyunjaya P, et al. Ocular complications after anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in medicare patients with age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(2):266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatment Trials (CATT) Research Group. Martin DF, Maguire MG, et al. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: 2-year results. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(7):1388–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.IVAN Study Investigators. Chakravarthy U, Harding SP, et al. Ranibizumab versus bevacizumab to treat neovascular age-related macular degeneration: 1-year findings from the IVAN randomized trial. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(7):1399–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sheyman AT, Cohen BZ, Friedman AH, Ackert JM. An outbreak of fungal endophthamitis after intravitreal injection of compounded combined bevacizumab and triamcinolone. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(7):864–869. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.88. A report of an outbreak of endophthalmitis associated with contaminated bevacizumab plus triamcinolone from a compounding pharmacy

- 15. Goldberg RA, Flynn HW, Jr, Miller D, Gonzalez S, Isom RF. Streptococcus endophthalmitis outbreak after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab: 1-year outcomes and investigative results. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(7):1448–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.12.009. A report of a severe outbreak of endophthalmitis associated with contaminated bevacizumab from a compounding pharmacy.

- 16.Yamashiro K, Tsujikawa A, Miyamoto K, et al. Sterile endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab obtained from a single batch. Retina. 2010;30(3):485–490. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181bd2d51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan P, Khan L, Mondal P. Cluster endophthalmitis following multiple intravitreal bevacizumab injections from a single use vial. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013 doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.99855. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Entezari M, Ramezani A, Ahmadieh H, Ghasemi H. Batch-related sterile endophthalmitis following intravitreal injection of bevacizumab. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013 doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.111192. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma S, Johnson D, Abouammoh H, Hollands S, Brissette A. Rate of serious adverse effects in a series of bevacizumab and ranibizumab injections. Can J Ophthalmol. 2012;47(3):275–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunningham MA, Tlucek P, Folk JC, Boldt HC, Russell SR. Sequential, acute noninfectious uveitis associated with separate intravitreal injections of bevacizumab and ranibizumab. Retin Cases Brief Rep. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e3182964f7c. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang F, Yu S, Liu K, et al. Acute intraocular inflammation caused by endotoxin after intravitreal injection of counterfeit bevacizumab in Shanghai, China. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(2):355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schachat AP, Rosenfeld PJ, Liesegang TJ, Stewart MW. Endophthalmitis is not a “never event”. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(8):1507–1508. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCannell CA. Meta-analysis of endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents: causative organisms and possible prevention strategies. Retina. 2011;31(4):654–661. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31820a67e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen E, Lin MY, Cox J, Brown DM. Endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection: the importance of Viridans streptococci. Retina. 2011;31(8):1525–1533. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318221594a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wen JC, McCannel CA, Mochon AB, Garner OB. Bacterial dispersal associated with speech in the setting of intravitreous injections. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(12):1551–1554. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doshi RR, Leng T, Fung AE. Reducing oral flora contamination of intravitreal injections with face mask or silence. Retina. 2012;32(3):473–476. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0B013E31822C2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimada H, Hattori T, Mori R. Minimizing the endophthalmitis rate following intravitreal injections using 0.25% povidoneiodine irrigation and surgical mask. Gaefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthlamol. 2013;251(8):1885–1890. doi: 10.1007/s00417-013-2274-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romero-Aroca P, Sararols L, Arias L, Casaroli-Marano RP, Bassaganyas F. Topical azithromycin or ofloxacin for endophthalmitis prophylaxis after intravitreal injection. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:1595–1599. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S35795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Falavarjani KG, Modarres M, Hashemi M, et al. Incidence of acute endophthalmitis after intravitreal bevacizumab injection in a single clinical center. Retina. 2013;33(5):971–974. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31826f0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheung CS, Wong AW, Lui A, et al. Incidence of endophthalmitis and use of antibiotic prophylaxis after intravitreal injections. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(8):1609–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhavsar AR, Stockdale CR, Ferris FL, et al. Update on risk of endophthalmitis after intravitreal drug injections and potential impact of elimination of topical antibiotics. Arch Ophthlamol. 2012;130(6):809–810. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin VT, Wesibrod DJ, Eng KT, et al. Antibiotic resistance of ocular surface flora with repeated use of a topical antibiotic after intravitreal injection. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(4):456–461. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alabiad CR, Miller D, Schiffman JC, Davis JL. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of ocular and nasal flora in patients undergoing intravitreal injections. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(6):999–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abell RG, Kerr NM, Allen P, Vote BJ. Intravitreal injections: is there benefit for a theatre setting? Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(12):1474–1478. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tabandeh H, Boscia F, Sborgia A, et al. Endophthalmitis associated with intravitreal injections: office-based setting and operating room setting. Retina. 2013 doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000008. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ikuno Y, Sawa M, Tsujikawa M, et al. Effectiveness of 1.25% povidone-iodine combined with topical levofloxacin against conjunctival flora in intravitreal injection. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2012;56(5):497–501. doi: 10.1007/s10384-012-0160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lad EM, Maltenfort MG, Leng T. Effect of lidocaine gel anesthesia on endophthalmitis rates following intravitreal injection. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2012;43(2):115–120. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20120119-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen SD, Mohammed Q, Bowling B, Patel CK. Vitreous wick syndrome: a potential cause of endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection of triamcinolone through the pars plana. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(6):1159–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christoforidis JB, Williams MM, Epitropoulos FM, Knopp MV. Subconjunctival bleb that forms at the injection site after intravitreal injection is drug, not vitreous. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;41(6):614–615. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woo SJ, Han JM, Ahn J, et al. Bilateral same-day intravitreal injections using a single vial and molecular bacterial screening for safety surveillance. Retina. 2012;32(4):667–671. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31822c296b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tabatabaii A, Ahmadraji A, Khodabande A, Mansouri M. Acute bilateral endophthalmitis following bilateral intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) injection. Middle East Afr J Ophthlamol. 2013;20(1):87–88. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.106402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kugu S, Sevim MS, Kaymak NZ, et al. Exogenous group G Streptococcus endophthalmitis following intravitreal ranibizumab injection. Clin Ophthlamol. 2012;6:1399–1402. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S31721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joshi L, Morarji J, Tomkins-Netzer O, Lightman S, Taylor SR. Rhizobium radiobacter endophthalmitis following intravitreal ranibizumab injection. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2012;3(3):283–285. doi: 10.1159/000342693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pinarci EY, Yesilirmak N, Bayar SA, et al. The results of pars plana vitrectomy and silicone oil tamponade for endophthalmitis after intravitreal injections. Int Ophthalmol. 2013;33(4):361–365. doi: 10.1007/s10792-012-9702-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaudhary KM, Romero JM, Ezon I, Fastenberg DM, Deramo VA. Pars plana vitrectomy in the management of patients diagnosed with endophthalmitis following intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injection. Retina. 2013;33(7):1407–1416. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182807659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gonzalez S, Rosenfeld PJ, Stewart MW, Brown J, Murphy SP. Avastin doesn’t blind people, people blind people. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(2):196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shienbaum G, Flynn HW., Jr Compounding bevacizumab for intravitreal injection: does USP h797i always apply? Retina. 2013;33(9):1733–1734. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31829f742c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schimel AM, Scott IU, Flynn HW., Jr Endophthalmitis after intravitreal injections: should the use of face masks be the standard of care? Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(12):1607–1609. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wykoff CC, Flynn HW, Jr, Rosenfeld PJ. Prophylaxis for endophthalmitis following intravitreal injection: antisepsis and antibiotics. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(5):717–719. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen RW, Rachitskaya A, Scott IU, Flynn HW. Is the use of topical antibiotics for intravitreal injections the standard of care or are we better off without antibiotics? JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(7):840–842. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]