Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to describe the impacts of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) from the patients’ perspective, and to inform the development of a conceptual model.

Methods

Focus groups and one-on-one interviews were undertaken in adult patients with IBD. Transcripts from the focus groups and interviews were analyzed to identify themes and links between themes, assisted by qualitative data software MaxQDA. Themes from the qualitative research were supplemented with those reported in the literature and concepts included in IBD-specific patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures.

Results

Twenty-seven patients participated. Key physical symptoms included pain, bowel-related symptoms such as frequency, urgency, incontinence, diarrhea, passing blood, and systemic symptoms such as weight loss and fatigue. Participants described continuing and variable symptom experiences. IBD symptoms caused immediate disruption of activities but also had ongoing impacts on daily activities, including dietary restrictions, lifestyle changes, and maintaining close proximity to a toilet. More distal impacts included interference with work, school, parenting, social and leisure activities, relationships, and psychological well-being. The inconvenience of rectal medications, refrigerated biologics, and medication refills emerged as novel burdens not identified in existing PRO measures.

Conclusions

IBD symptoms cause immediate disruption in activities, but patients may continue to experience some symptoms on a chronic basis. The conceptual model presented here may be useful for identifying target concepts for measurement in future studies in IBD.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, Qualitative research, Conceptual model, Patient burden

INTRODUCTION

The chronic nature of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) leads to a significant impact on patients’ lives, beyond intestinal symptoms alone. The sequelae of this can be seen in the increased rates of depression, and reduced workforce participation reported in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn’s disease (CD) 1,2,3. In addition, the necessity for chronic medical therapies to maintain clinical remission of the disease generates its own obstacles for patients 4,5.

Several patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures have been developed for IBD with the goal of quantifying the holistic effects of these conditions. These PROs focus on the health-related quality of life impacts of this condition 6,7,8 but they each differ widely in content and, overall, lack coverage with respect to some important concepts9. Although IBD presents a substantial burden to patients’ lives, a conceptual model that fully describes the respective disease impacts has not yet been developed. Conceptual models characterize proximal and more distal impacts of a condition and the inter-relationships among them. These models provide a comprehensive picture of the burden of disease and can be used to identify areas in which treatment benefits may be observed. The objective of this study was to understand IBD and its treatment from the patient perspective to help inform a comprehensive conceptual model of IBD impacts.

METHODS

This was a qualitative study in which focus groups and one-on-one interviews were conducted with adults with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease to identify the impacts of IBD and its management, excluding surgery. To ensure comprehensive coverage, a review of published studies that included focus groups or qualitative interviews with IBD patients, and a content analysis of IBD-specific PRO measures, were also performed.

Qualitative research with patients

Participants were recruited through a tertiary clinical site specializing in the treatment of IBD. Patients were eligible if they were 18 years of age or older, had mild or moderate UC or CD at the time of interviews, and were currently prescribed mesalamine for maintenance of their IBD. Using a standardized moderator guide, a trained interviewer asked open-ended questions to elicit patients’ experiences of living with IBD, and to rate their IBD on a 0-10 bothersome scale, where 0=not at all bothersome and 10=extremely bothersome. Data were collected until information saturation was attained, i.e., until no new information was being identified. The focus groups and interviews were convened at the Beth Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, where full Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

Literature Review

A review of the literature in Medline, EMBASE, and PsychINFO databases was performed to identify qualitative research articles in adult patients with IBD, either UC and/or CD, with search terms that included ‘patient perspective,’ ‘qualitative,’ ‘focus group,’ and ‘interviews.’ There were no date restrictions. In addition, PRO measures that were developed to assess health-related quality of life impacts in patients with IBD were reviewed. In order to capture the impact of IBD managed medically, articles or PRO measures that focused solely on the impacts of surgery were excluded.

Analyses

Transcripts from the focus groups and one-on-one interviews were analyzed following the principles of Grounded Theory10 to identify themes and possible links between themes. Qualitative data analysis software MaxQDA (version 10.0) was used to code and facilitate organization of the data. In accordance with standard qualitative data analysis, a saturation table was constructed to assess data saturation 11. Themes that emerged from the qualitative research were compared with concepts reported in the literature and items in IBD-specific PRO measures to inform the development of a comprehensive conceptual model on the impacts of IBD and its treatment.

RESULTS

Twenty-seven patients (4 focus groups comprising 2-6 participants each and 10 one-on-one interviews) participated. The mean age was 31.5 years (range; 20-59), 52% (n=14) were male, and 78% (n=21) had UC, while 22% (n=6) had CD (Table 1). At the time of the interviews, 21/27 were in clinical remission (based on Simple Colitis Clinical Activity Index <2) but this was a disease-experienced cohort; the mean disease duration was 7 years, and 13/27 were also on maintenance immunomodulators or biologics due to prior moderate-severe disease. The focus groups were conducted prior to the individual interviews, and the evaluation of information saturation indicated that no new codes (themes) were added after the eighth one-on-one interview, demonstrating data saturation. A comparison of themes did not identify any differences in impacts between UC and CD patients.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | N=27 |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean ± SD | 31.5 ± 9 |

| Min, Max | 20, 59 |

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Male | 14 (52%) |

| Female | 13 (48%) |

|

| |

| Disease duration (years) | |

| Mean ± SD | 6.5 ± 6 |

| Min, Max | 1, 20 |

|

| |

| Prior intestinal surgery | 1 (4%) |

|

| |

| Diagnosis | |

| Ulcerative Colitis | 21 (78%) |

| Crohn’s Disease | 6 (22%) |

|

| |

| Currently in clinical remission | 21 (78%) |

|

| |

| Current maintenance medication | |

| Asacol ® | 12 (44%) |

| Lialda ® | 11 (41%) |

| Pentasa ® | 4 (15%) |

|

| |

| Mesalamine schedule | |

| Once-a-day | 15 (55%) |

| Twice-a-day | 9 (33%) |

| Three times-a-day | 3 (12%) |

|

| |

| Concomitant immunomodulators | 13 (48%) |

Patient-Reported Burden of IBD

The key concepts associated with the burden of IBD identified by participants interviewed in this study are highlighted in Table 2. These included physical symptoms of disease, resulting in immediate impaired functioning, and broader impacts on lifestyle, daily activities (including work, school, and parenting), social and leisure activities, relationships, and psychological well-being. Example quotes from participants in the focus groups/interviews are provided to illustrate concepts (Supplementary Table 1). Notable findings from each theme are described below;

Table 2.

IBD impacts reported by study participants, in literature, and IBD-specific PRO measures

| Concept | Reported by Participants | Reported in Literature(12-32) | Item in IBD-specific PROa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate Impacts | |||

| Disrupted activities | X | X | CDPWDG, IBDQ, IBDQ-36, IBDSI, RFIPC, WPAI-CD |

| Embarrassment, worry, fear | X | X | CDPWDG, IBDQ, IBDQ-36, IBDSI, RFIPC, |

| Hospitalization | X | X | |

| Lifestyle Impacts | |||

| Take medication | X | X | |

| Restrict diet | X | X | |

| Modify behaviors (eg, sleep, stress) | X | X | |

| Maintain close proximity to toilet | X | X | |

| Take precautions against incontinence (eg, using pads such as ‘Depend products’) | X | ||

| Impacts on Daily Activities | IBDSI | ||

| Absence from school/work | X | X | CDPWDG, IBDQ, IBDQ-36, IBDSI, WPAI-CD |

| Impaired work performance | X | IBDSI, WPAI-CD | |

| • due to symptoms | X | X | CDPWDG, IBDQ-36 |

| • due to medication or side effects | X | CDPWDG, WPAI-CD | |

| • due to lack of/difficulty accessing toilet | X | X | CDPWDG |

| Problems at work due to IBD | X | X | CDPWDG |

| Disability/ loss of job due to IBD | X | CDPWDG | |

| Change job/ career /delay in education | X | X | RFIPC |

| Difficulty with household tasks | X | WPAI-CD | |

| Difficulties in role as parent | X | ||

| Disturbed sleep | X | IBDQ, IBDQ-36, IBDSI | |

| Impacts on Social and Leisure Activities | |||

| Delay or cancel activity | X | X | IBDQ, IBDQ-36 |

| Difficulty planning in advance | X | X | |

| Avoiding events | X | X | IBDQ, IBDSI |

| Restricted participation in events | X | IBDQ, IBDQ-36 | |

| • due to lack of toilet facilities | X | X | IBDQ-36 |

| • due to food restrictions | X | ||

| Participating in activities associated with disease relapse (eg, drinking alcohol, eating restricted foods) | X | X | |

| Impacts on Relationships | X | IBDQ-36, IBDSI | |

| Alienation from family and friends | X | X | |

| Being a dependent/burden on others | X | X | RFIPC |

| Perceived lack of understanding/support | X | IBDQ | |

| Withdraw from dating | X | X | |

| Difficulties with intimacy | X | X | RFIPC |

| Limited sexual activity | X | IBDQ, IBDQ-36, IBDSI | |

| Break-up/divorce | X | ||

| Treatment Impacts | |||

| Side effects | X | X | RFIPC |

| Difficulty finding effective treatment | X | X | |

| Pill burden | |||

| • reluctance to take any medication | X | X | |

| • pill characteristics | X | X | |

| • number/timing of doses | X | X | |

| • reminder of illness | X | X | |

| Inconvenience | |||

| • applying rectal medications | X | ||

| • need to refrigerate medications | X | ||

| • carrying medications | X | X | |

| • refilling prescriptions | X | ||

| • visits to physician/hospital | X | X | |

| Financial burden | X | X | |

| Psychological Impacts | |||

| Feelings of loss of control | X | X | IBDSI, RFIPC |

| • unpredictability of daily symptoms | X | X | |

| • unpredictability of flare | X | X | |

| Altered self concept | IBDSI | ||

| • change in body image | X | RFIPC | |

| • loss of attractiveness | X | X | IBDSI |

| • difficulty in identity as chronically ill | X | X | |

| • adapting to new bowel habits | X | X | |

| • lowered self esteem | X | IBDSI | |

| Embarrassment/Stigma/Humiliation | IBDQ, IBDSI | ||

| • symptoms of IBD (eg, incontinence, noises, flatulence) | X | X | IBDQ-36 |

| • feeling dirty, smelly | X | IBDSI, RFIPC | |

| • being treated as different | RFIPC | ||

| • taking medication, many pills | X | X | |

| • need to hide IBD, pills at work | X | X | CDPWDG |

| Fear/worry | IBDSI | ||

| • being incontinent | X | X | IBDQ |

| • having a flare | X | X | IBDQ, IBDQ-36 |

| • side effects/long term effects of medications | X | X | RFIPC |

| • never feeling better | IBDQ, IBDQ-36 | ||

| • treatment will cease to be effective | X | X | |

| • future treatment options | X | X | |

| • disease progression | X | X | IBDQ |

| • need for surgery | X | X | IBDQ, IBDQ-36 |

| • need for stoma/ostomy | X | X | |

| • developing cancer | X | X | IBDQ, IBDQ-36 |

| • death/shortened lifespan | RFIPC | ||

| • fertility/pregnancy | X | X | RFIPC |

| • passing IBD to offspring | X | IBDQ-36, RFIPC | |

| Emotional Impacts | IBDQ-36 | ||

| • frustrated/discouraged | X | X | IBDQ, IBDQ-36 |

| • anxious | X | IBDQ, IBDSI | |

| • tearful, upset | X | IBDQ, IBDQ-36, IBDSI | |

| • depressed | X | X | CDPWDG, IBDQ, IBDQ-36, IBDSI |

| • irritable | X | IBDQ, IBDQ-36, IBDSI | |

| • angry | X | X | IBDQ, IBDQ-36, IBDSI |

| • mood swings | X | X | |

| • self-blame /guilt | X | X | |

| • hopelessness | X | IBDSI | |

| Impaired cognitive functioning | X | IBDSI |

CDPWDG: Crohn’s Disease Perceived Work Disability Questionnaire34

IBDQ: Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (32 items)6

IBDQ-36: Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (36 items)33

IBDSI: Inflammatory Bowel Disease Stress Index8

RFIPC: Rating Form of IBD Patient Concerns7

WPAI-CD: Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Crohn’s Disease35

Symptom Patterns

Even during periods of ‘remission,’ participants reported symptoms that fluctuated in severity from day to day. Although participants used the terms ‘flares’ and ‘remission,’ they described highly variable symptom experiences in these 2 states indicating some overlap. For example, participants described ‘bad’ or ‘gigantic’ flares that were associated with very severe symptoms, but they also reported ‘mild flares,’ or having ‘the beginnings’ of a flare which they curtailed by resting, altering medications, using an enema, or adding other medications. None of these were classified by the participant as an actual flare. Participants emphasized that, even during remission, their bowel habits would not generally be considered ‘normal’ by the general public. When asked about how bothersome their IBD is (on a 0-10 scale), participants typically reported a 10 (range 8-10) during a flare, but still gave ratings of 2-6 for how they typically feel, when not experiencing a flare, depending on what they eat, concerns about ‘having it in the background’ and not being able to plan ahead not knowing how they will feel.

Impact on Lifestyle

We identified 4 key impacts on lifestyle; taking medication, restricting diet, modifying behaviors that triggered symptoms, and maintaining close proximity to toilets. These, in turn, had significant other impacts on patients’ functioning. Although an effective medication permitted them more freedom in food choices, participants still reported the need to be careful in avoiding certain trigger foods. Despite their efforts, not all participants successfully identified ‘triggers.’ Participants reported that despite doing everything ‘right,’ they might still experience a flare, and this resulted in discouragement and frustration.

Impacts on Daily Activities

Participants reported absences from work or school during a flare due to pain, fatigue, and frequency. The likelihood of flares or dealing with recurrent symptoms also impacted patients’ career plans. Participants also reported trying to manage work stresses more effectively in order to prevent escalation of symptoms. Interview participants reported having to cancel trips or events if their symptoms unexpectedly worsened. The unpredictability of their symptoms resulted in difficulty in planning ahead and, in everyday life, they often avoided certain activities, such as camping and travel, or reported that their social life was restricted by the need to maintain close proximity to toilets or because of dietary restrictions.

Impacts on Relationships

While partners, family, and friends are generally perceived to be supportive, some participants described others as lacking in understanding. Participants reported that it was difficult to disclose their IBD to new friends or a potential partner; a ‘major hurdle to overcome’ because of the nature of the disease.

Psychological impacts

Coming to terms with having a chronic, lifelong illness was reported to be a challenge, particularly in a relatively young population. Participants reported being acutely embarrassed by their IBD symptoms and humiliated if they had fouled themselves in public. They reported being self-conscious about taking their medication in social settings or what others thought on seeing the number of pills required. This was especially difficult for young adults. Fears of having a flare and being incontinent were highly prominent among participants. Participants expressed additional fears and concerns regarding their disease and treatments. Disease-related concerns included those related to the future course of their disease, possible shortened lifespan, and the risk of developing cancer.

Treatment Impacts

Taking medication itself resulted in a number of impacts, including side effects, the need to try several medications before identifying an effective treatment, embarrassment, inconvenience, and financial burden. Regimens that require more than one dose per day, and particularly those that required a mid-day dose, were reported to be more burdensome. For many, the goal was to reduce doses to the minimum necessary to control symptoms.

Treatment-related concerns included those about possible long-term effects of their current treatments, worry that their current treatment would cease to be effective, concerns regarding the availability of other treatment options, and the need to progress to more ‘serious’ medications or to surgery. Participants wanting to start a family or have additional children were concerned about their disease or medications affecting their pregnancy and of the possibility of passing on IBD to their offspring.

Development of Conceptual Model

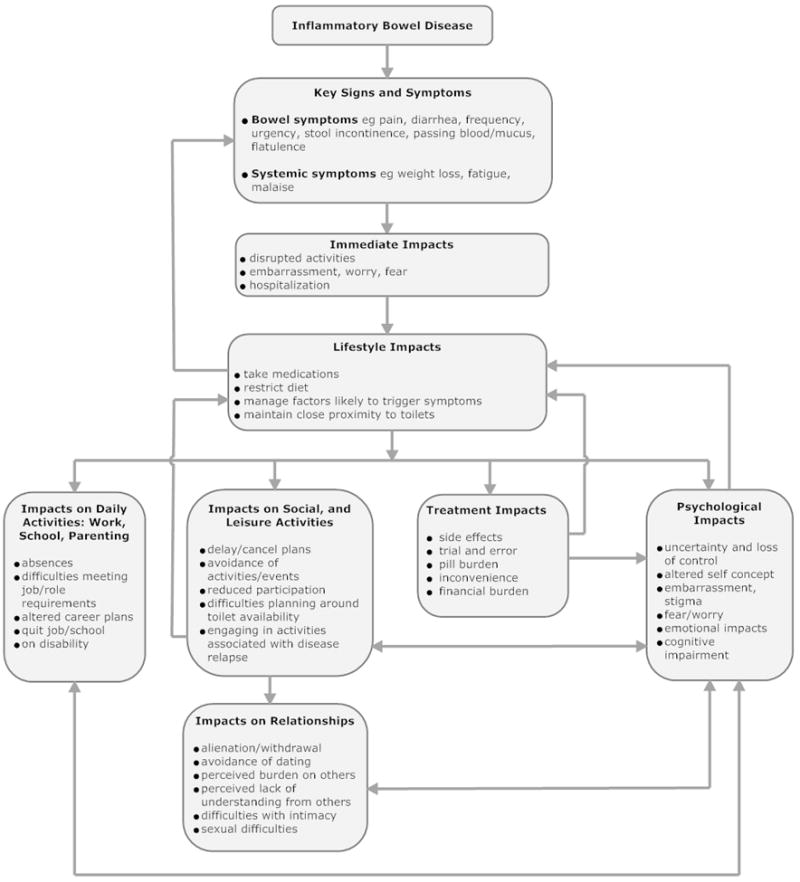

The literature search of qualitative research articles in IBD yielded 454 abstracts. Within these, 28 articles discussing patient-reported impacts of IBD were identified for full-text review, of which 21 had convened focus groups or one-on-one interviews and thus were included in this evaluation12-32. Additional details from these studies are provided to supplement the descriptions of concepts elicited from study participants (Table 2). The 6 most widely used and established IBD-specific health-related quality of life measures9 were reviewed: the Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBDQ)6Questionnaire, a 36-item version of the IBDQ 33, the Crohn’s Disease Perceived Work Disability Questionnaire(CDPWDG)34, the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Stress Index (IBDSI)8, the Rating Form of IBD Patient Concerns (RFIPC7, and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Crohn’s Disease (WPAI-CD) 35. Concepts captured by items in the IBD-specific PRO measures were added to those identified by the focus groups, interviews, and qualitative studies in the literature to produce an inventory of all concepts identified by each of these 3 sources. As can be seen from Table 2, some novel burdens of disease were identified by this study, which do not appear in existing PROs. These data informed the development of a conceptual model of disease and treatment impacts (Figure 1). In this model, each arrow indicates the direction of influence. For example, one arrow from treatment impacts indicates that these have psychological impacts on patients, while a second arrow leading up to lifestyle impacts illustrates that the impacts of treatment influence patients taking their medication.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of Impacts of Inflammatory Bowel Disease.

DISCUSSION

This research presents a comprehensive inventory of the key symptoms and impacts of IBD from both qualitative research with patients as well as the literature. This study supports and expands on themes reported in the literature and captured by PRO measures developed for use in IBD. A notable addition is the presentation of the impacts of IBD treatments. There have been a number of studies in this population but, to our knowledge, this is the first attempt to consolidate the findings from all of these to provide a fully comprehensive picture of the burden of IBD.

The symptoms of IBD include both gastrointestinal and systemic symptoms, which disrupt immediate activities and cause embarrassment and worry to patients. These immediate impacts result in a cascade of effects on a patient’s life and psychological well-being. Symptoms and impacts are particularly severe during flares and as flares can occur more than once a year36, presenting a significant burden. However, even during remission, patients may not be entirely symptom-free and the overlap in symptoms between flare and remission states is supported by reports in the literature29,37. Even when symptoms appear to have completely remitted, it may be several months before patients feel sufficiently secure that their symptoms are truly under control so that they regain confidence to engage in normal activities28. Current findings, supported by the literature, illustrate the ongoing impacts of living with IBD even when not experiencing an episode typically referred to as a flare27.

With no available cure, IBD is managed by medication and changes in lifestyle, which include changes in diet, reducing stress38 and ensuring sufficient sleep in order to minimize the likelihood of worsening symptoms or initiating a flare. Patients report the need, or perceived need, always to maintain proximity to a toilet in case of an urgent need to defecate. These changes in turn, have further direct and indirect impacts on work/school/home and parenting, social and leisure activities, relationships and psychological well-being, as illustrated in the conceptual model.

IBD has significant psychological impacts due to fluctuating daily symptoms and the unpredictability of exacerbations or flares, embarrassment and stigma of IBD symptoms, fears related to long-term effects of treatments, treatment effectiveness, and progression of disease which can cause anxiety, depression, and other emotional effects38. Although no cognitive impairments were identified in the current focus groups or interviews, these are evident in the literature31 and there are items enquiring about difficulties in memory, concentration, and decision-making in IBD-specific PRO measures8). The burden of taking IBD medications and patients’ negative perceptions of these treatments can adversely affect treatment adherence, with consequences for disease management. To our knowledge, the immediate impacts of treatment for IBD have previously not been fully addressed or captured in the existing PRO measures.

The findings suggest no substantial differences between UC and CD with respect to symptoms and impacts, in line with other studies which report many more similarities than differences when comparing results by IBD diagnosis39,40,41 but further evaluation of the model comparing UC and CD would be beneficial.

Strengths and limitations of the research, however, need to be taken into account when drawing conclusions from the findings. The qualitative research involved 2 modes of data collection, focus groups and interviews, thus minimizing any potential limitations that may exist with either of these methods. Despite demonstrating information saturation within the data collected, the sample size was small and there are likely biases in the patients sampled for the qualitative research; these are limitations of the study. Furthermore, the PROs identified for review are the most widely used, but there may be other, lesser-known measures that include concepts not currently identified. Finally, we have not yet validated the conceptual model in a novel cohort of patients.

The results of a recent review of IBD-specific measures suggested some important areas may be missing9. By supplementing the content of PRO measures with findings from qualitative research, in this study we have been able to identify and add specific concepts, otherwise missing, to ensure greater coverage. Despite extensive coverage in development, we recommend further evaluation of the comprehensiveness of the concepts and their interactions described in the proposed model. Furthermore, the objectives were to capture the impacts of IBD in adults managed medically and so the impacts on children and the specific difficulties in having an ostomy bag after surgery are not included in this model.

CONCLUSIONS

This is the first study to present a comprehensive conceptual model of the impacts of IBD. The conceptual model resulting from this study illustrates IBD symptoms and impacts and the inter-relationships among them, capturing both acute and long-term impacts. Drawing from multiple sources it provides a more comprehensive model than previously available and helps to portray the full burden of IBD, including the impact of IBD treatments, from the patient perspective. The conceptual model presented here may be useful for identifying target concepts for measurement in future studies in IBD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Unrestricted funding for the patient interviews and focus groups and for the literature research was provided by Shire Development LLC, Wayne, PA. We thank Emuella Flood for assistance with the focus groups and patient interviews.

Funding - ACM is supported by NIH grant K23DK084338 and the generosity of Doris Toby Axelrod & Lawrence J. Marks. The study design, implementation and analysis were independent of the funding sources.

Disclosures - ACM has served on Advisory Boards for Janssen, Abbott, and UCB, and received research funding from Shire, Salix and Proctor & Gamble. ASC has served on Advisory Boards for Janssen, Abbott, and UCB.

References

- 1.Netjes JE, Rijken M. Labor participation among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013 Jan;19(1):81–91. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longobardi T, Jacobs P, Bernstein CN. Work losses related to inflammatory bowel disease in the United States: results from the National Health Interview Survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 May;98(5):1064–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuller-Thomson E, Sulman J. Depression and inflammatory bowel disease: findings from two nationally representative Canadian surveys. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Aug;12(8):697–707. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200608000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lachaine J, Yen L, Beauchemin C, Hodgkins P. Medication adherence and persistence in the treatment of Canadian ulcerative colitis patients: analyses with the RAMQ database. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013 Jan 30;13:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rocchi A, Benchimol EI, Bernstein CN, Bitton A, Feagan B, Panaccione R, Glasgow KW, Fernandes A, Ghosh S. Inflammatory bowel disease: a Canadian burden of illness review. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012 Nov;26(11):811–7. doi: 10.1155/2012/984575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine EJ, Singer J, Williams N, Goodacre R, et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:804–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li Z, Mitchell M, Zagami EA, Patrick DL. The Rating Form of IBD Patient Concerns: A new measure of health status. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:701–712. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joachin G, Milne B. Inflammatory bowel disease: effects on lifestyle. J Adv Nurs. 1987;12:483–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1987.tb01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Achleitner U, Goenen M, Colombel J-F, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sahakyan N, Cieza A. Identification of areas of functioning and disability addressed in inflammatory bowel disease-specific patient reported outcome measures. J Crohn’s and Colitis. 2012;6:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joffe H, Yardley L. Content and thematic analysis. In: Marks DF, Yardley L, editors. Research Methods for Clinical and Health Psychology. London: Sage; 2004. pp. 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerr C, Nixon A, Wild D. Assessing and demonstrating data saturation in qualitative inquiry supporting patient reported outcomes research. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10:269–281. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brydolf M, Segesten K. Living with ulcerative colitis: experiences of adolescents and young adults. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1996;23:39–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb03133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper JM, Collier J, James V, Hawkey CJ. Beliefs about personal control and self-management in 30-40 year olds living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2010;47:1500–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniel JM. Young adults’ perceptions of living with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology Nursing. 2002;25:83–94. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudley-Brown S. Living with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology nursing: the official journal of the Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates. 1996;19:60–64. doi: 10.1097/00001610-199603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fletcher PC, Schneider MA. Is there any food I can eat? Living with inflammatory bowel disease and/or irritable bowel syndrome. Clinical nurse specialist. 2006;20:241–247. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200609000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fletcher PC, Schneider MA, Van R, V, Leon Z. I am doing the best that I can!: Living with inflammatory bowel disease and/or irritable bowel syndrome (part II) Clinical nurse specialist. 2008;22:278–285. doi: 10.1097/01.NUR.0000325382.99717.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fletcher PC, Jamieson AE, Schneider MA, Harry RJ. “I know this is bad for me, but…”: a qualitative investigation of women with irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease: part II. Clinical nurse specialist. 2008;22:184–191. doi: 10.1097/01.NUR.0000311707.32566.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerson MJ, Grega CH, Nathan-Virga S. Three kinds of coping: Families and inflammatory bowel disease. Fam Syst Med. 1993;11:55–65. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall NJ, Rubin GP, Dougall A, Hungin AP, Neely J. The fight for ‘health-related normality’: a qualitative study of the experiences of individuals living with established inflammatory bowel disease (ibd) Journal of Health Psychology. 2005;10:443–455. doi: 10.1177/1359105305051433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall NJ, Rubin GP, Hungin AP, Dougall A. Medication beliefs among patients with inflammatory bowel disease who report low quality of life: a qualitative study. BMC Gastroenterology. 2007;7:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-7-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodgkins P, Swinburn P, Solomon D, Yen L, Dewilde S, Lloyd A. Patient preferences for first-line oral treatment for mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: a discrete-choice experiment. The Patient: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. 2012;5:33–44. doi: 10.2165/11595390-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawakami A, Tanaka M, Ochiai R, Naganuma M, Iwao Y, Hibi T, et al. Difficulties in taking aminosalicylates for patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology Nursing. 2012;35:24–31. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0b013e31824033f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynch T, Spence D. A qualitative study of youth living with Crohn disease. Gastroenterology Nursing. 2008;31:224–230. doi: 10.1097/01.SGA.0000324114.01651.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mukherjee S, Sloper P, Turnbull A. An insight into the experiences of parents with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;37:355–363. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller KR, Prosser R, Bampton P, Mountifield R, Andrews JM. Female gender and surgery impair relationships, body image, and sexuality in inflammatory bowel disease: Patient perceptions. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2010;16:657–663. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norton BA, Thomas R, Lomax KG, Dudley-Brown S. Patient perspectives on the impact of Crohn’s disease: results from group interviews. Patient Preferences and Adherence. 2012;6:509–520. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S32690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pihl-Lesnovska K, Hjortswang H, Ek AC, Frisman GH. Patients’ perspective of factors influencing quality of life while living with Crohn disease. Gastroenterology Nursing. 2010;33:37–44. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0b013e3181cd49d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prince A, Whelan K, Moosa A, Lomer MC, Reidlinger DP. Nutritional problems in inflammatory bowel disease: the patient perspective. Journal of Crohn’s & colitis. 2011;5:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waljee AK, Joyce JC, Wren PA, Khan TM, Higgins PDR. Patient reported symptoms during an ulcerative colitis flare: A Qualitative Focus Group Study. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2009;21:558–564. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328326cacb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolfe BJ, Sirois FM. Beyond standard quality of life measures: The subjective experiences of living with inflammatory bowel disease. Quality of Life Research. 2008;17:877–886. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9362-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zutshi M, Hull TL, Hammel J. Crohn’s disease: A patient’s perspective. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2007;22:1437–1444. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0332-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Love JR, Irvine EJ, Fedorak RN. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:15–19. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199201000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vergara M, Montserrat A, Casellas F, Gallardo O, Suarez D, Motos J, et al. Development and validation of the Crohn’s Disease Perceived Work Disability Questionnaire. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2350–2357. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reilly MC, Gerlier L, Brabant Y, Brown M. Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire in Crohn’s disease. Clin Ther. 2008;30:393–404. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gray JR, Leung E, Scales J. Treatment of ulcerative colitis from the patient’s perspective: a survey of preferences and satisfaction with therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:1114–1120. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henriksen M, Jahnsen J, Lygren I, Sauar J, Kjellevold O, Schulz T, et al. Ulcerative colitis and clinical course: Results of a 5-year population-based follow-up study (The IBSEN Study) Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2006;7:543–550. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000225339.91484.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sajadinejad MS, Asgari K, Molavi H, Kalantari M, Adibi P. Psychological issues in inflammatory bowel disease: An overview. Gastroenterology Res and Pract. 2012;2012:106502. doi: 10.1155/2012/106502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitchell A, Guyatt G, Singer J, Irvine EJ, Goodacre R, Tompkins C, et al. Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1988;10:306–310. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198806000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lix LM, Graff LA, Walker JR, Clara I, Rawsthorne P, Rogala L, et al. Longitudinal study of quality of life and psychological functioning for active, fluctuating, and inactive disease patterns in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1575–1584. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Graff LA, Vincent N, Walker JR, Clara I, Carr R, Ediger J, et al. A population-based study of fatigue and sleep difficulties in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1882–1889. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.