Abstract

Lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of diseases that arise from the constituent cells of the immune system or from their precursors. 18F-fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) is now the cornerstone of staging procedures in the state-of-the-art management of Hodgkin's disease and aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. It plays an important role in staging, restaging, prognostication, planning appropriate treatment strategies, monitoring therapy, and detecting recurrence. However, its role in indolent lymphomas is still unclear and calls for further investigational trials. The protean PET/CT manifestations of lymphoma necessitate a familiarity with the spectrum of imaging findings to enable accurate diagnosis. A meticulous evaluation of PET/CT findings, an understanding of its role in the management of lymphomas, and knowledge of its limitations are mandatory for the optimal utilization of this technique.

Keywords: Imaging, lymphoma, PET/CT

Introduction

Lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of diseases that arise from the constituent cells of the immune system or from their precursors.[1] They are known to arise from virtually any organ or tissue in the body. 18F-fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) has become a standard procedure for the evaluation of lymphomas.[2] Their protean imaging manifestations necessitate familiarity with the spectrum of imaging findings to enable accurate diagnosis. An understanding of the role of FDG PET/CT in the management of lymphomas and knowledge of its limitations is mandatory for the optimal utilization of this technique.

Lymphomas are broadly classified into two main groups: Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) and Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL). NHL is more common and represents nearly 85% of lymphomas.[3] Based on histological characteristics and tumor cell phenotype, HL is subdivided into the classical and non-classical types. The former has four histological subtypes – nodular sclerosis (the most common), lymphocyte predominance (with the most favorable prognosis), mixed cellularity, and lymphocyte depletion, while the latter includes the nodular lymphocyte predominant type.[4] NHL can broadly be classified into two prognostic groups: The aggressive and the indolent lymphomas, the latter group having a better prognosis, with a median survival spanning about 10 years. Of the aggressive lymphomas, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common, accounting for about 30% of cases, followed by mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, which represent 6 and 8% of NHL cases, respectively. The most common type of indolent lymphoma is the follicular lymphoma (FL) which represents 22% of NHL cases, followed by marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) and small-cell lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) representing 6 and 8% of cases, respectively.[3]

PET/CT in Initial Staging

Staging of lymphomas is a vital pre-requisite to their appropriate therapeutic management and prognostication. This is based on the Ann Arbor system, to which has been added a definition of bulky disease called the Cotswald modification.[5] Imaging modalities have a fundamental role in the staging of lymphomas. CT is the most commonly used imaging modality for staging malignant lymphoma because of its widespread availability and relatively low cost.[6] However, CT lacks functional information, which impedes identification of disease in normal-sized organs and detection of lesions that have poor contrast with the surrounding tissue.[7] Another weakness of CT is that it is not reliable in the detection of bone marrow disease, which, if present, by definition indicates stage IV disease.[8] CT also subjects the patient to ionizing radiation, which may induce second cancers.[7] Each CT scan, covering the neck, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis, is associated with an effective dose of approximately 20-25 mSv.[7] This is for contrast-enhanced ones: The radiation dose incurred during a whole-body PET/CT scan with the incorporation of a diagnostic quality CECT is approximately 25 mSv in each examination.[9] This is not significantly different from that of a routine diagnostic whole-body CECT. The effective dose in a stand-alone whole-body PET study is approximately 3.3-7.6 mSv per examination.[10] The greatest contributor to the radiation burden incurred is thus from CT, which has contributed to doses ranging from 2.7 to 54.2 mSv, depending on individual protocols.[11] The ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) principle must be borne in mind while performing a PET/CT study, to reduce the radiation dose, without sacrificing diagnostic information.

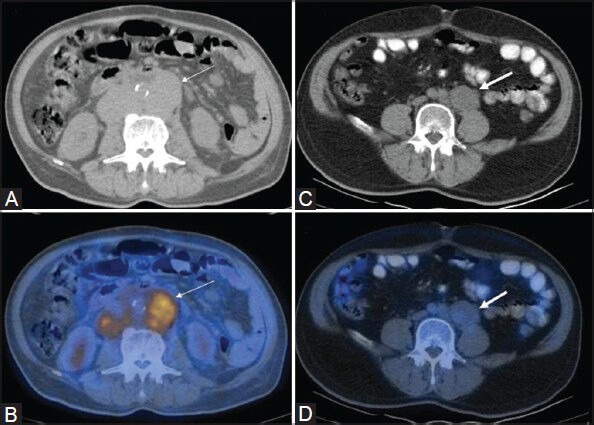

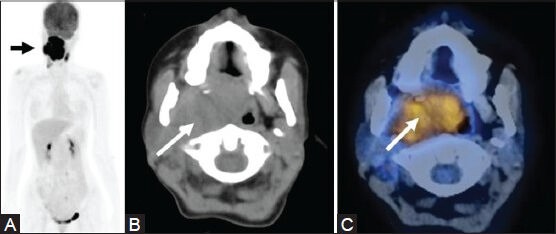

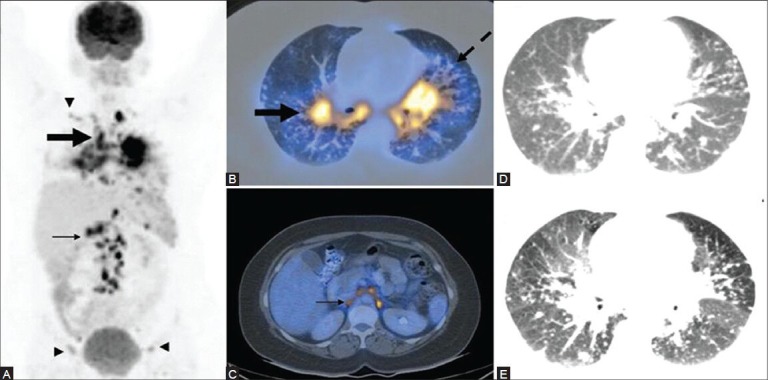

The usefulness of 18F-FDG PET in the initial staging of lymphoma has been demonstrated in several studies. The main advantage over anatomical imaging techniques, such as CT, is its ability to detect metabolic changes in the areas involved with malignant lymphoma before the structural changes become visible. It can detect more lesions than CT [Figure 1] and may lead to a change in the stage of up to 8-20% of patients.[12,13] PET may upstage or pick up occult lesions such as splenic [Figure 2], bone marrow [Figure 3], osseous, and with gastrointestinal involvement [Figure 4] which may otherwise be missed on conventional CT.[14] A high level of concordance has been observed between the sites of focal FDG uptake in the bone marrow and bone marrow biopsy. In fact, PET scans have demonstrated a high negative predictive value to exclude bone marrow involvement. This holds particularly true for early-stage HL, and may even obviate the need for bone marrow biopsy in this group.[14] Another major advantage of FDG-PET/CT is that since it is a whole-body imaging method, it can guide the biopsy from a metabolically active and easily accessible site.

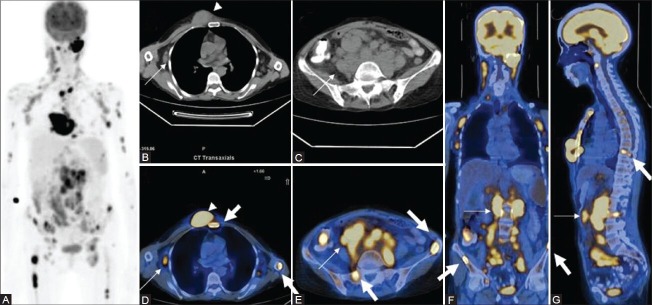

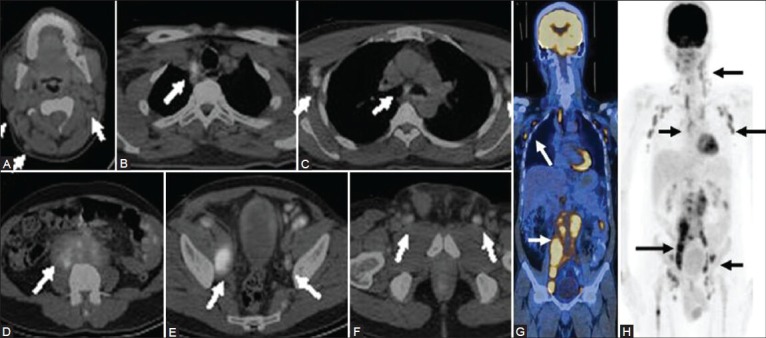

Figure 1 (A-G).

Maximal intensity projection (MIP) image (A) in a patient of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) shows extensive sites of involvement visualized as areas of increased FDG uptake. Transaxial CT images (B, C) Show axillary and abdominal lymphadenopathy (thin arrows) and a large subcutaneous nodule (arrowhead). Fused PET/CT images (axial D, E; coronal F; and sagittal G) show sites of bone marrow involvement (thick arrows) in the sternum, spine, and iliac crest, over and above the lesions picked up on CT

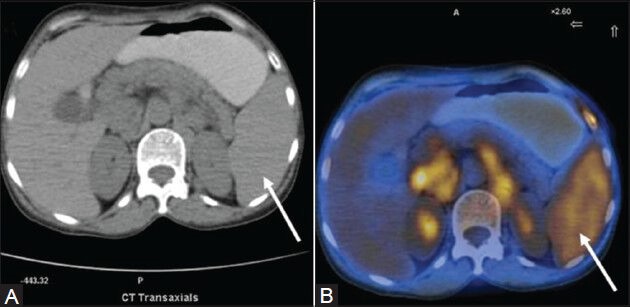

Figure 2 (A, B).

A case of HL (mixed cellularity type): Spleen appears unremarkable on transaxial CT image (arrow in A). PET/CT fusion image at corresponding site shows diffusely increased FDG uptake (arrow in B)

Figure 3 (A, B).

Transaxial CT image at the level of upper thigh (A) In a case of NHL (DLBCL) appears unremarkable. PET/CT fusion image at the corresponding site (B) intense FDG uptake in the bone marrow of proximal right femoral shaft (arrow) suggestive of marrow involvement

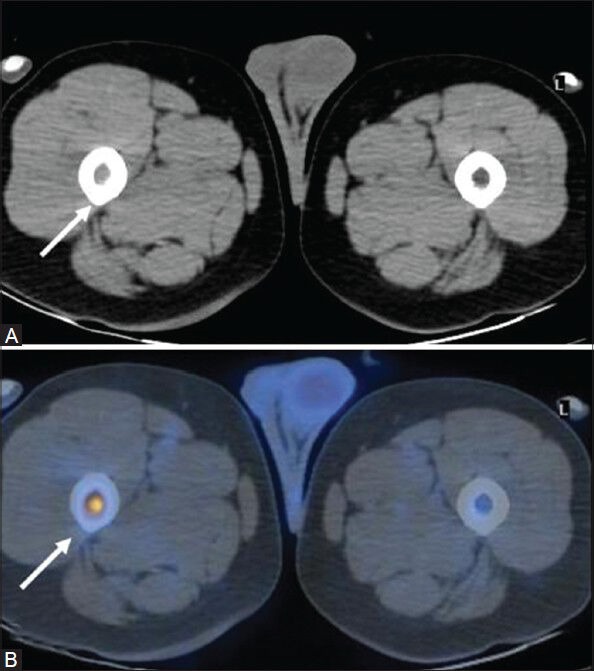

Figure 4 (A, B).

Transaxial PET/CT fusion image (B) In a case of DLBCL shows intense FDG uptake in the small bowel loop (arrow). This was picked up only on retrospect (arrow) in the corresponding CT image (A)

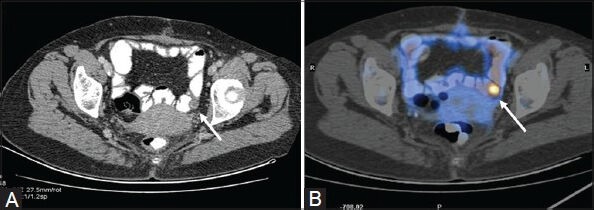

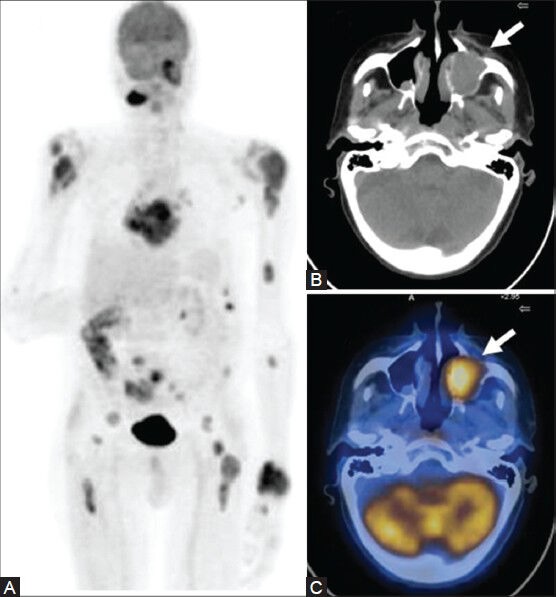

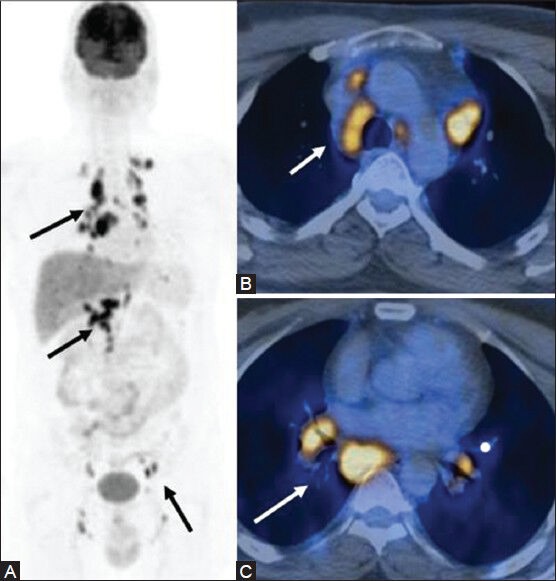

The ability of PET to differentiate indolent from aggressive lymphomas has been the subject of many studies. Routinely, HL and aggressive NHL like DLBCL [Figure 5A, B] and grade III FLs are FDG avid.[15] However, some subtypes of NHL, predominantly the indolent lymphomas such as MZLs [Figures 5C, D, and 6] and peripheral T-cell lymphomas may have low or even no uptake of FDG.[15,16] Albeit PET/CT provides significantly more accurate information compared to PET and CT for the staging and re-staging of patients with indolent lymphoma,[17] caution is warranted in these histologic subtypes of NHL because a negative FDG PET scan does not necessarily rule out disease; complimentary anatomical imaging [CECT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)] is mandatory to increase the detection rate of the lesions. PET/CT also has the potential to detect transformation of a low-grade lymphoma to a more aggressive subtype (Richter transformation)[18] based on the degree of FDG avidity.

Figure 5 (A-D).

Transaxial CT (A) and PET/CT (B) images in a case of DLBCL showing FDG-avid retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy (thin arrows). Retroperitoneal lymph node involvement (thick arrows) is also visualized on CT (C) in a case of MZL, which shows very poor FDG avidity on the PET/CT fusion image (D)

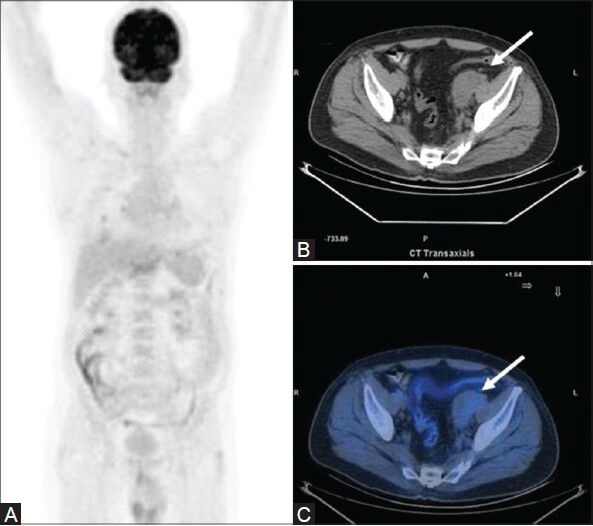

Figure 6 (A-C).

A case of low-grade FL: MIP image (A) appears unremarkable. Transaxial CT image (B) an enlarged pelvic lymph node mass (arrow), with poor FDG avidity on the fused PET/CT image (C)

The degree of FDG uptake can be expressed quantitatively by means of the Standardized Uptake Value (SUV). It represents the activity in the lesion in µCi/ml corrected for the weight of the patient and the dose of FDG administered. A study by Ngeow et al.[14] showed that an FDG uptake of more than 10 SUV is predictive of an aggressive B-cell lineage or suggestive of the presence of a more aggressive histological component. Another study by Schoder et al.[19] showed that all indolent lymphomas had an SUV of less than 13, while 35% of aggressive lymphomas also had an SUV of less than 13. Despite the overlap between the two, the study concluded that aggressive disease had a higher 18F-FDG uptake than did indolent lymphomas (P < 0.01) and the authors suggested that an SUV of more than 10 confers a higher likelihood for aggressive disease. This has important diagnostic and therapeutic implications. PET/CT plays an important role in arriving at an accurate diagnosis. It can be used to detect sites that may be more accessible for biopsy and guide biopsies to the site of highest FDG uptake, representing the most aggressive site of lymphoma.[20] It may thus play an important role in identifying the foci of aggressive transformation or aggressive histology in those patients who were thought to harbor an indolent lymphoma on previous biopsy.[14] Owing to the differential pattern of FDG avidity, PET can potentially detect two separate clones at the same time. Biopsy of the lesions with intense uptake will help identify a separate clone (if only lesions with moderate uptake have been sampled before). This additional information, which cannot be obtained on conventional morphological imaging, has utmost clinical relevance, as these patients require more aggressive therapy.

PET/CT in Evaluation of Treatment Response

Evaluating therapeutic response is vital to the management of lymphoma patients. This information is a must to tailor the therapy in each patient depending upon the individualized response. With a larger and more effective arsenal of therapeutic regimens currently available, it is important to optimize treatment strategies to achieve maximal disease control with minimal toxicity to the patient. Therapeutic response is assessed based on clinical, histopathologic, and imaging criteria. CT has been hitherto the most commonly used imaging modality. A decrease in size of the tumor mass has been the cornerstone in establishing a good therapeutic response. However, a residual mass picked up on CT may not necessarily be metabolically active. The inclusion of PET/CT has addressed some of the limiting factors of CT, which include: the size criteria for lymph node involvement, the differentiation of unopacified bowel from lesions in the abdomen and pelvis, the inability to distinguish viable tumor from necrotic/fibrotic lesions after therapy, and the characterization of small lesions.[21]

18F-FDG PET has been shown to be able to distinguish between post-treatment fibrosis and viable tumor [Figure 7]. In this regard, 18F-FDG PET has a higher specificity (92% vs. 17%, P < 0.01), accuracy (96% vs. 63%, P < 0.05), and positive predictive value (94% vs. 60%, P < 0.05) than does CT.[22] In a recently published retrospective analysis of 75 patients with HD or aggressive NHL treated with standard chemotherapy regimens with or without radiation therapy whose disease was restaged with PET and CT, a correlation was found between positive findings on restaging PET and clinical relapse.[23] Studies have also documented the utility of PET to assess the response to treatment with radiolabeled antibodies.[24]

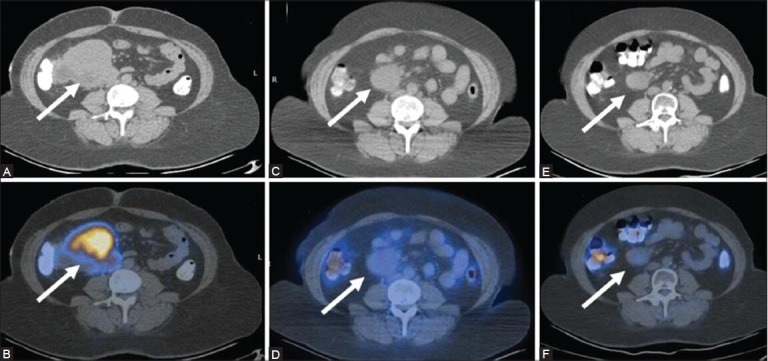

Figure 7 (A-F).

A case of mesenteric lymphoma: Top panel - CT images, bottom panel - PET/CT images. Inital scan (Feb 09) (A, B) Before the onset of therapy shows an FDG-avid mesenteric lymph node mass (arrows). The mass has reduced in size, but still persists on CT (C) In the post-therapy scan (Jan 10). Corresponding PET/CT image (D) No uptake indicating complete metabolic resolution. A follow-up scan (July 10) in the absence of therapy shows further reduction in the size of the mass on CT (E), with persistently absent FDG uptake on the PET/CT fusion image (F)

PET/CT studies have been found useful to assess the therapeutic response during the course of chemotherapy [Figure 8]. This is interim PET evaluation or early PET study. Conventional imaging methods are inadequate in this realm as tumor shrinkage takes time, and cannot be used as the basis for early monitoring of response to treatment.

Figure 8 (A-F).

A case of HL (lymphocyte predominant type): Pre-therapy scan shows a large FDG-avid left axillary lymph node mass as seen on the MIP (A) Cornonal (B), and transaxial (C) PET/CT images. The interim scan performed after 3 cycles of chemotherapy is negative as seen on the corresponding PET/CT images (D-F)

Most responders will become PET negative after two to three cycles of standard chemotherapy. A study of 121 patients with NHL, which assessed the utility of 18F-FDG PET after 2-3 cycles of chemotherapy found that 18F-FDG PET had a high predictive value for progression-free survival and overall survival.[25] Another study evaluated 18F-FDG uptake on PET before and after 1 cycle of chemotherapy in 30 patients with NHL or HD. Negative PET findings in that study were highly predictive of remission, with 87% of the patients in complete remission after a median of 19 months of follow-up.[26] PET/CT has outperformed CT in the evaluation of therapeutic response as early as after 1-2 cycles of chemotherapy.[27] The interim scan, however, may show evidence of partial or incomplete response. One study performed on HL and NHL patients used visual and quantitative analysis of FDG uptake performed before and after 1-2 cycles of chemotherapy.[28] At the end of a 2-year follow-up, they concluded that a 60% reduction in SUV in the interim scan is a reliable criterion to distinguish the responders from the non-responders. A negative scan is thus not mandatory to identify a responder. The Deauville criteria, laid by a consensus committee of nuclear medicine physicians, hematologists, and oncologists recommends a 5-point scale rather than taking a binary decision (namely PET positive or negative). This is based upon visual analysis, with background uptake as reference. International validation studies are on to assess the utility of these criteria.[29] Recognition of early therapeutic response or failure enables the treatment to be adjusted accordingly. Several ongoing trials are under way to assess the impact of treatment adaptation based on early 18F-FDG PET results on overall survival.[30]

With the widespread use of PET, the need to revise the existing guidelines for lymphoma staging was felt.[31] The consensus recommendations regarding the use of FDG-PET for assessment response published by the International Harmonization Project in 2007 state that in routinely FDG-avid lymphomas, such as DLBCL and HL, a Complete Response (CR) is assigned to all patients with a negative PET scan regardless of the presence of a residual mass on CT. In cases in which there is residual disease on PET (PET-positive patients), a partial response, stable disease, or progressive disease can be assigned based on the response shown by CT; the Unconfirmed Complete Response (Cru) category has been eliminated.[32]

Spectrum of PET/CT Findings in Lymphoma

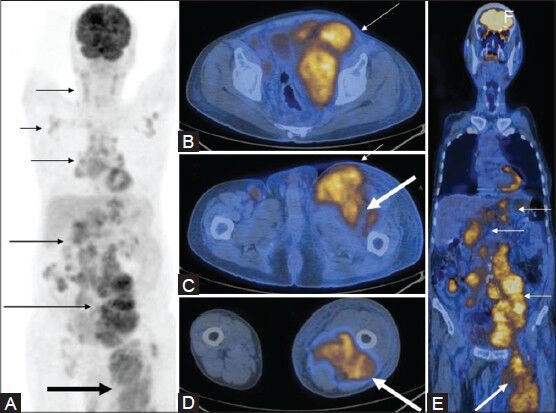

As the name suggests, lymph nodes are the most commonly affected sites in lymphoma – be it cervical, supraclavicular, axillary, mediastinal, abdominal, or inguinal [Figure 9]. Extranodal lymphoma occurs in about 40% of patients with lymphoma.[33] It is observed more frequently in NHL than with HL, and is often intermediate to high grade.[34] The incidence of extranodal lymphoma is higher in patients with AIDS and immunodeficient states.[35,36] Lymphomatous nodes appear discretely enlarged or as soft-tissue masses, with variable FDG avidity depending on the histological type.

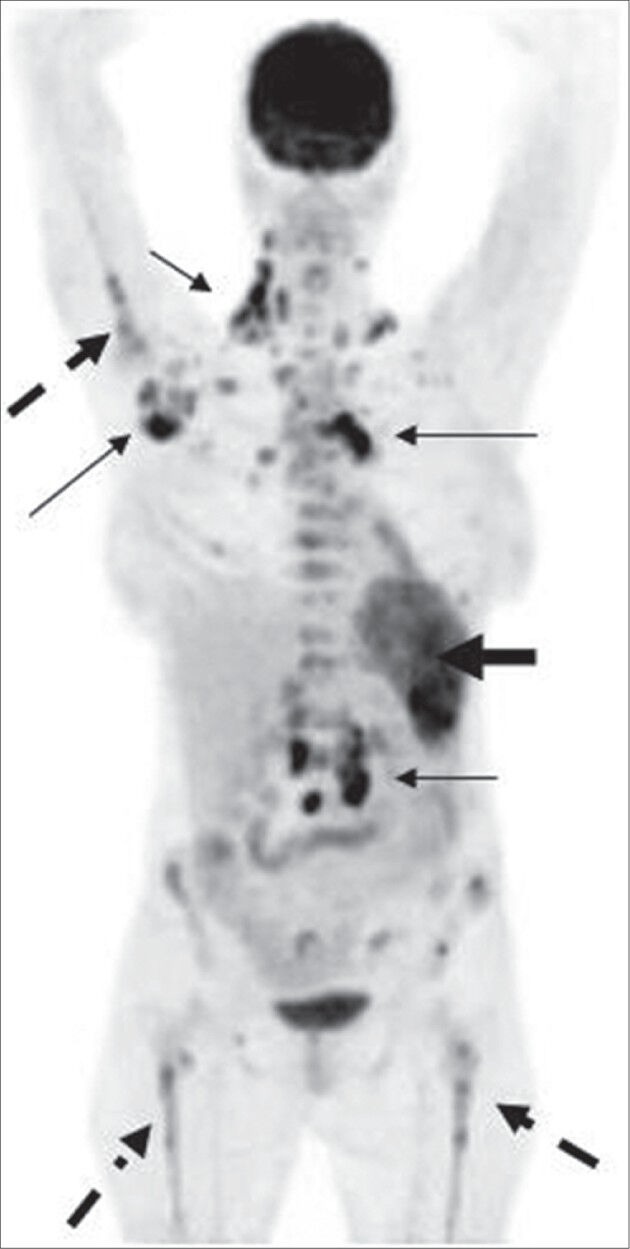

Figure 9 (A-H).

Extensive lymphadenopathy in a case of NHL (DLBCL): Transaxial PET/CT fusion images in gray scale show cervical (A) mediastinal (B) axillary (C) retroperitoneal (D) pelvic (E) and inguinal (F) lymph node involvement (arrows), which is also well seen on the coronal fused PET/ CT (G) and MIP images (H)

Extranodal Abdominal Manifestations

The most commonly involved extranodal abdominal site is the spleen, followed by the liver, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, abdominal wall, genitourinary tract, adrenal, peritoneal cavity, and biliary tract in that order.[37] Both hepatic and splenic involvement may occur in the form of diffuse infiltration with or without organomegaly [Figure 10] and as focal nodules. PET/CT outperforms conventional imaging in the evaluation of hepatosplenic involvement. In the gastrointestinal tract, the stomach, small bowel, pharynx, large bowel, and esophagus are involved in decreasing order of frequency.[38] The pattern of involvement may be diffusely infiltrative, polypoidal, ulcerative, or nodular [Figure 11]. The interpretation of positive PET/CT findings in the gastrointestinal tract may be challenging owing to physiological FDG uptake in the large bowel and to a lesser extent in the stomach and small bowel.[39] Diffuse uptake has most often been observed to be associated with normal colonoscopy, whereas focal uptake is often pathological.[40] Simple maneuvers like delayed imaging, negative oral contrast like water, or diluted positive oral contrast agents[41] often help to resolve the issue. Subtle lymphomatous bowel deposits that may be missed on CT are well visualized on PET/CT in aggressive NHL and HL. Pancreatic involvement may be diffuse (resembling pancreatitis) in the form of focal masses or as secondary involvement from adjacent lymph nodes. Renal involvement may be in the form of solitary or multiple masses, diffuse infiltration, and spread from adjacent nodes. Peritoneal lymphomatosis is rare and closely mimics carcinomatosis.[42] It presents as peritoneal nodules, infiltrative masses, and ascites [Figure 12]. PET/CT is highly sensitive in the detection of peritoneal involvement in FDG-avid lymphomas.

Figure 10.

MIP image in a case of NHL shows extensive FDG uptake in the spleen (thick arrow). Also noted is the presence of multiple sites of bone marrow (dotted arrow) and lymph node (thin arrow) involvement

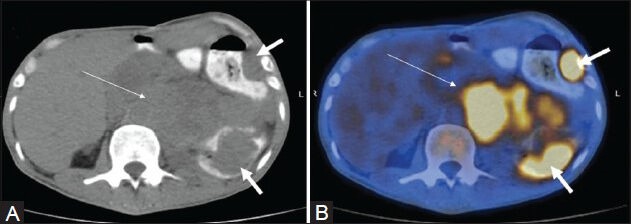

Figure 11 (A, B).

Transaxial CT (A) and PET/CT images (B) in a case of NHL (mantle cell type) showing bulky lymphadenopathy (thin arrow) with bowel involvement (thick arrow)

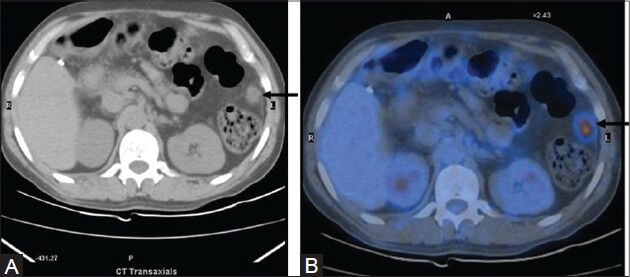

Figure 12.

Transaxial CT and PET/CT images in a case of NHL which shows an FDG-avid mesenteric nodule suggestive of lymphomatous spread into the peritoneum

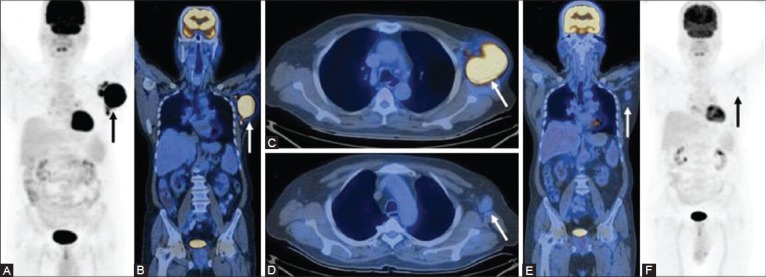

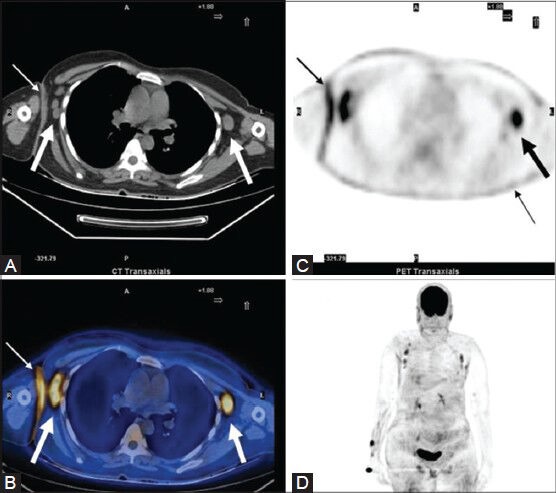

Intrathoracic Manifestations

Intrathoracic disease is noted in 40-50% of patients with NHL at presentation, compared with 85% of those with HL.[43] Pulmonary involvement presents as solitary or multiple nodules [Figure 13] or masses, reticulonodular opacities, and consolidation.[44] Accurate characterization of pulmonary lesions on PET/CT requires diagnostic quality breath-hold CT, preferably high-resolution CT (HRCT). The FDG avidity is variable, depending on the histological type. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy can vary in extent and in size and may manifest as a large solitary mass or as discrete nodes within masses of matted nodes. HL most commonly affects the anterior mediastinal group, while NHL involvement is more diffuse. Interpretation of the PET/CT scan needs to be performed with caution, as FDG uptake is seen in inflammatory lymphadenopathy as well.[45]

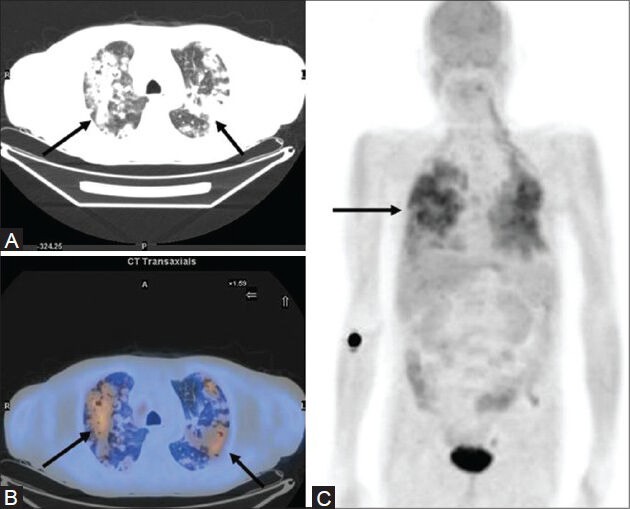

Figure 13 (A-C).

A case of NHL showing extensive pulmonary involvement on the MIP image (C) which is seen as multiple nodular opacities (arrows) showing confluence on transaxial CT image (A) with increased FDG uptake on the PET/CT fusion image (B)

Secondary pleural, pericardial [Figure 14], chest wall, and diaphragmatic involvement is also known. Primary cardiac lymphomas are very rare.

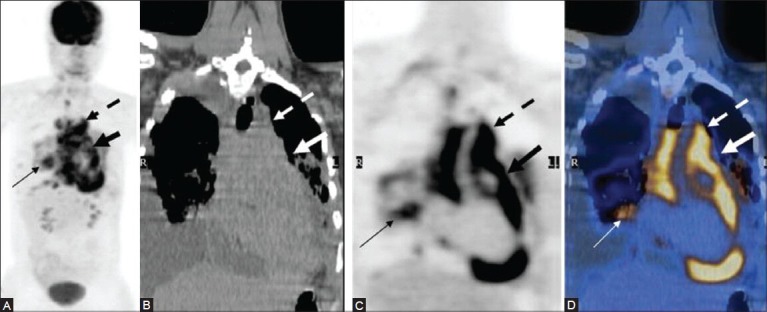

Figure 14 (A-D).

A case of mediastinal lymphoma with pericardial involvement: Mediastinal lymphadenopathy (dotted arrow) with pericardial encasement (thick arrow) and associated pulmonary involvement (thin arrow) well seen on the MIP (A) CT (B) PET (C) and fused PET/CT (D) images

CNS and Head and Neck Lymphomas

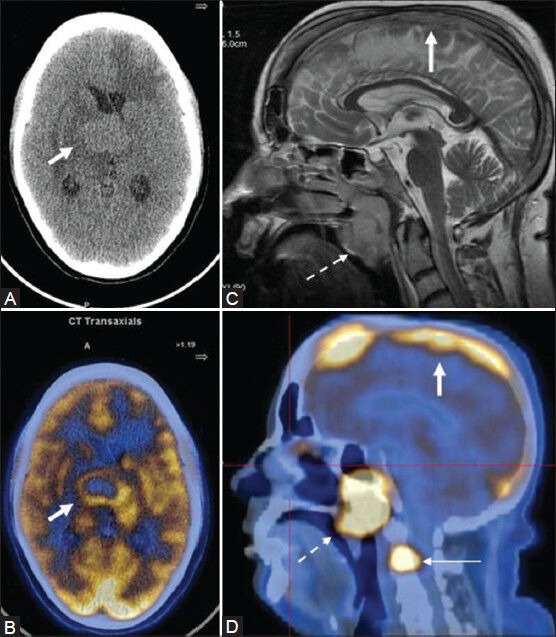

Intracranial lymphoma [Figure 15] which is seen almost exclusively with NHLs manifests as discrete masses or infiltrations involving the corpus callosum, deep gray matter structures, and periventricular regions.[46] Meningeal infiltration may be seen in the form of subarachnoid nodules, diffuse leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, or dural masses. FDG PET has been found useful in the management of AIDS patients with CNS lesions. It is often not possible for CNS lymphomas to be distinguished from toxoplasmosis in the immunocompromised patient on the basis of conventional morphological imaging due to the similarity in appearance. However, CNS lymphomas show high FDG uptake, unlike toxoplasmosis, making it possible to distinguish the two.[47] This can potentially avoid invasive diagnostic procedures and enable the early initiation of therapy.

Figure 15 (A-D).

A young female AIDS patient with primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL): NCCT head (A) A rounded hyperdense lesion in the deep gray matter and periventricular region, which shows intense peripheral uptake on the fused PET/CT image (B) Another case of NHL (stage IV) showing a tumor thrombus in the superior sagittal sinus on MR (C) corresponding to an area of intense FDG uptake on sagittal fused PET/CT (D thick arrow). Also, note the presence of FDG-avid nasopharyngeal lymph nodal mass (dotted arrow) and skeletal metastasis (thin arrow)

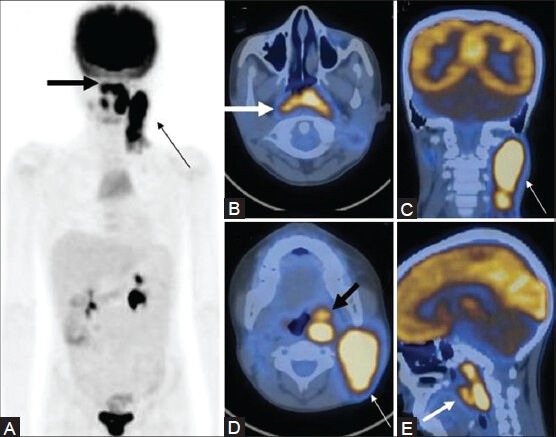

Lymphomatous masses of the head and neck may involve the Waldeyer's ring, including nasopharynx [Figure 16], base of tongue, tonsils [Figure 17], and soft palate. Lymphomatous infiltration of the paranasal sinuses [Figure 18] appears as a nonspecific soft-tissue mass partially or completely obscuring the involved lumen. Destruction of the surrounding bone may be associated. Jaw involvement, which usually occurs in Burkitt's lymphoma, presents as an FDG-avid lytic lesion with associated soft-tissue component.[1]

Figure 16 (A-E).

A case of NHL showing nasopharyngeal involvement extending inferiorly into the oropharynx (thick arrow), with bulky cervical lymphadenopathy (thin arrow) on the MIP (A) and transaxial , coronal, and sagittal PET/CT fusion images (B-E)

Figure 17 (A-C).

A case of tonsillar B-cell lymphoma with extensive local spread (arrow) as seen on MIP (A) CT (B) and fused PET/CT (C) Images

Figure 18 (A-C).

A case of B-cell type of NHL showing extensive involvement on the MIP image (A) Also note the FDG-avid soft-tissue mass in the left maxillary sinus with associated bone destruction (arrow) on the CT (B) and PET/CT fusion images (C)

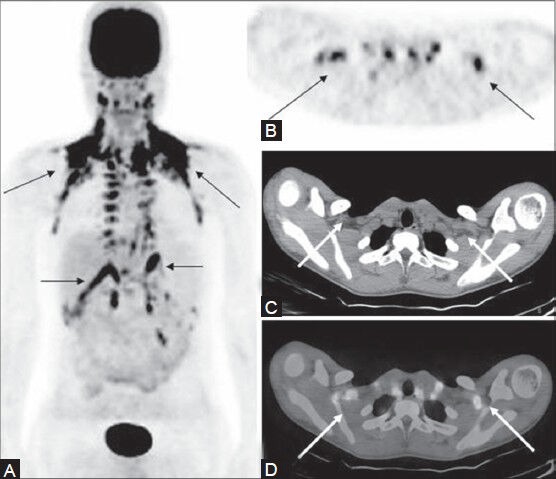

Musculoskeletal Manifestations

Lymphomas may involve the bone marrow or cortical bone. Several studies have shown that 18F-FDG PET is accurate in evaluating the presence of bone marrow disease and scores over CT in this regard. However, diffusely increased 18F-FDG uptake in the bone marrow may be seen owing to marrow hyperplasia post-chemotherapy or due to granulocyte colony-stimulating factors, and thus hamper identification of actual marrow involvement. This increased uptake generally returns to baseline levels by 1 month.[12] Primary lymphomas frequently involves the appendicular skeleton, whereas secondary lymphomas more frequently affect the spine.[48] They are present as FDG-avid lytic or mixed lytic-sclerotic lesions.

PET/CT is also highly sensitive in picking up lymphomatous deposits in the subcutaneous tissue and in the underlying muscle [Figure 19]. They are visualized as hypermetabolic nodules against the background of normal soft-tissue structures.

Figure 19 (A-E).

MIP image (A) in a case of NHL shows extensive lymphadenopathy (thin arrows) with increased FDG uptake in the left lower limb (thick arrow). Axial (B-D) and coronal (E) PET/CT fusion images at multiple levels show the FDG-avid bulky lymph nodes (thin arrows), with associated muscle involvement in the left lower limb (thick arrow)

Cutaneous Lymphoma

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma accounts for approximately 6% of all cases of NHL and includes two clinical entities with similar histopathologic features: Mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sιzary syndrome (SS).[49] For staging MF [Figure 20] and SS, PET/CT has been found to be more sensitive than CT alone in detecting lymph node involvement, and may thus provide more accurate staging and prognostic information.[50]

Figure 20 (A-D).

A case of MF: CT image (A) Bilateral axillary lymph nodes (thick arrows). Also, note the site of skin thickening (thin arrow) in the right axilla. The same sites show increased FDG uptake on the PET (C) and fused PET/CT (B) images. Note that the lymph nodes that are normal in size on CT are FDG-avid on PET. Also, the diffuse cutaneous involvement is much better appreciated on the PET images. This is seen as areas of diffusely increased FDG uptake on the MIP image (D) which also gives an overall picture of the sites of lymph node involvement

Pitfalls of PET/CT

Benign conditions with increased glycolysis, such as infection, inflammation, and granulomatous disease, may also lead to increased FDG uptake,[51] and be mistaken for lymphomatous deposits [Figures 21, 22]. Inflammatory changes secondary to surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy may also lead to false-positive results, if the study is performed soon after these interventions.[52] Further, systemic conditions that lead to generalized lymphadenopathy may mimic malignant lymphoma.[53] Renal involvement may be difficult to assess owing to physiological excretion of the tracer. Additionally, sites of high physiological uptake such as the brain, myocardium, gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, lymphoid tissue, brown adipose tissue, salivary glands, and thymus may obscure or mimic the presence of tumor deposits. However, the use of CT co-registration largely circumvents this problem [Figure 23]. Bone marrow hyperplasia secondary to chemotherapy with or without cytokines, such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, may lead to increased FDG uptake up to 3 weeks after the last dose of cytokines. Similar effects can be seen in the spleen.[54] Hence, attention to the timing of the scan is crucial. FDG PET/CT may be falsely negative in certain histological subtypes of NHL such as MZLs, peripheral T-cell lymphomas, small lymphocytic lymphomas, and primary FLs. In these cases, conventional morphological imaging techniques such as CT or MRI are a must. Bowel involvement may be negative on FDG PET/CT, especially in low-grade lymphomas. In certain cases such as the marginal zone mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, the lesions may evade visualization both on FDG PET and on CT and be picked up on endoscopy or endoscopic ultrasonography.[55] Another disadvantage of FDG PET/CT is exposure of the patient to ionizing radiation; the effective dose is variable depending upon individual protocols. A meticulous evaluation of PET/CT findings, along with a detailed history, clinical examination, and knowledge of the histological type is a pre-requisite to accurate interpretation.

Figure 21 (A-D).

A case of systemic sarcoidosis: MIP image (A) Mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy with pulmonary involvement (thick arrow) and abdominal (thin arrow), supraclavicular and inguinal lymphadenopathy (arrowheads). PET/CT images (B, C) Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (thick arrow) with reticulonodular lesions along thickened nodular bronchovascular bundles (dotted arrow) and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy (thin arrow). A provisional diagnosis of lymphoma was made based on the above findings. Biopsy proved it to be a case of sarcoidosis. Note the visualization of better detail on the HRCT image (E) compared to the routine CT image (D)

Figure 22 (A-C).

A case of disseminated Koch's masquerading as lymphoma: MIP image (A) Multiple sites of lymph node involvement (arrows). Transaxial PET/CT fusion images (B, C) sites of increased FDG uptake in the enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes

Figure 23 (A-D).

A follow-up case of HL (nodular sclerosis type) post-therapy: Multiple sites of FDG uptake (thin arrow) noted on the MIP image (A) in this patient on remission. These FDG-avid sites are well seen on the PET image (B) However, CT image (C) is unremarkable. Fused PET/CT image in inverted gray scale (D) localizes these sites of uptake to brown adipose tissue (arrow)

Conclusion

18F-FDG PET/CT is now the cornerstone of staging procedures in the state-of-the-art management of HL and aggressive NHL. It plays an important role in staging, restaging, prognostication, planning appropriate treatment strategies, monitoring therapy, and detecting recurrence. The role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in indolent lymphomas is still unclear and calls for further investigational trials.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Toma P, Granata C, Rossi A, Garaventa A. Multimodality imaging of Hodgkin Disease and Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas in children. Radiographics. 2007;27:1335–54. doi: 10.1148/rg.275065157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutchings M, Barrington S. PET/CT for therapy response assessment in lymphoma. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(Suppl 1):S21–30. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu P. Staging and classification of lymphoma. Semin Nucl Med. 2005;35:160–4. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Küppers R, Engert A, Hansmann ML. Hodgkins lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3439–47. doi: 10.1172/JCI61245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lister TA, Crowther D, Sutcliffe SB, Glatstein E, Canellos GP, Young RC, et al. Report of a committee convened to discuss the evaluation and staging of patients with Hodgkin's disease: Cotswolds meeting. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1630–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.11.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armitage JO. Staging non-Hodgkin lymphoma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:368–76. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.6.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwee TC, Kwee RM, Nievelstein RA. Imaging in staging of malignant lymphoma: A systematic review. Blood. 2008;111:504–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-101899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vinnicombe SJ, Reznek RH. Computerised tomography in the staging of Hodgkin's disease and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30(Suppl 1):S42–55. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brix G, Lechel U, Glatting G, Ziegler SI, Münzing W, Müller SP, et al. Radiation exposure of patients undergoing whole-body dual-modality 18F-FDG PET/CT examinations. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:608–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barentsz J, Takahashi S, Oyen W, Mus R, De Mulder P, Reznek R, et al. Commonly used imaging techniques for diagnosis and staging. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3234–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chawla SC, Federman N, Zhang D, Nagata K, Nuthakki S, McNitt-Gray M, et al. Estimated cumulative radiation dose from PET/CT in children with malignancies: A 5-year retrospective review. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:681–6. doi: 10.1007/s00247-009-1434-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moog F, Bangerter M, Diederichs CG, Guhlmann A, Kotzerke J, Merkle E, et al. Lymphoma: Role of whole-body 2-deoxy-2-[F-18]fluoro-D-glucose (FDG) PET in nodal staging. Radiology. 1997;203:795–800. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.3.9169707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naumann R, Beuthien-Baumann B, Reiss A, Schulze J, Hänel A, Bredow J, et al. Substantial impact of FDG PET imaging on the therapy decision in patients with early-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:620–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ngeow JY, Quek RH, Ng DC, Tao M, Lim LC, Tan YH, et al. High SUV uptake on FDG–PET/CT predicts for an aggressive B-cell lymphoma in a prospective study of primary FDG–PET/CT staging in lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1543–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsukamoto N, Kojima M, Hasegawa M, Oriuchi N, Matsushima T, Yokohama A, et al. The usefulness of (18) F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography ((18) F-FDG-PET) and a comparison of (18) F-FDG-pet with (67) gallium scintigraphy in the evaluation of lymphoma: Relation to histologic subtypes based on the World Health Organization classification. Cancer. 2007;110:652–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elstrom R, Guan L, Baker G, Nakhoda K, Vergilio JA, Zhuang H, et al. Utility of FDG-PET scanning in lymphoma by WHO classification. Blood. 2003;101:3875–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fueger BJ, Yeom K, Czernin J, Sayre JW, Phelps ME, Allen-Auerbach MS. Comparison of CT, PET, and PET/CT for Staging of Patients with Indolent Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009;11:269–74. doi: 10.1007/s11307-009-0200-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruzzi JF, Macapinlac H, Tsimberidou AM, Truong MT, Keating MJ, Marom EM, et al. Detection of Richter's transformation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia by PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1267–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schöder H, Noy A, Gönen M, Weng L, Green D, Erdi YE, et al. Intensity of 18fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in positron emission tomography distinguishes between indolent and aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4643–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bodet-Milin C, Kraeber-Bodéré F, Moreau P, Campion L, Dupas B, Le Gouill S. Investigation of FDG-PET/CT imaging to guide biopsies in the detection of histological transformation of indolent lymphoma. Haematologica. 2008;93:471–2. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, Gascoyne RD, Specht L, Horning SJ, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:579–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cremerius U, Fabry U, Neuerburg J, Zimny M, Osieka R, Buell U. Positron emission tomography with 18F-FDG to detect residual disease after therapy for malignant lymphoma. Nucl Med Commun. 1998;19:1055–63. doi: 10.1097/00006231-199811000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zinzani PL, Fanti S, Battista G, Tani M, Castellucci P, Stefoni V, et al. Predictive role of positron emission tomography (PET) in the outcome of lymphoma patients. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:850–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs SA, Vidnovic N, Joyce J, McCook B, Torok F, Avril N. Full-dose 90 Y ibritumomab tiuxetan therapy is safe in patients with prior myeloablative chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7146–50s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1004-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikhaeel NG, Hutchings M, Fields PA, O’Doherty MJ, Timothy AR. FDG-PET after two to three cycles of chemotherapy predicts progression-free and overall survival in high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1514–23. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kostakoglu L, Coleman M, Leonard JP, Kuji I, Zoe H, Goldsmith SJ. PET predicts prognosis after 1 cycle of chemotherapy in aggressive lymphoma and Hodgkin's disease. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:1018–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haioun C, Itti E, Rahmouni A, Brice P, Rain JD, Belhadj K, et al. 18 F Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) in aggressive lymphoma: An early prognostic tool for predicting patient outcome. Blood. 2005;106:1376–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torizuka T, Nakamura F, Kanno T, Futatsubashi M, Yoshikawa E, Okada H, et al. Early therapy monitoring with FDG-PET in aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and Hodgkin's lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:22–8. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1333-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kostakoglu L, Schöder H, Johnson JL, Hall NC, Schwartz LH, Straus DJ, et al. Interim [(18) F] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in stage I-II non-bulky Hodgkin lymphoma: Would using combined positron emission tomography and computed tomography criteria better predict response than each test alone? Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:2143–50. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.676173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hutchings M, Barrington SF. PET/CT for therapy response assessment in lymphoma. J Nucl Med. 2000;50(Suppl 1):S21–30. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delbeke D, Stroobants S, de Kerviler E, Gisselbrecht C, Meignan M, Conti PS. Expert opinions on positron emission tomography and computed tomography imaging in lymphoma. Oncologist. 2009;14:30–40. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-S2-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Juweid ME, Stroobants S, Hoekstra OS, Mottaghy FM, Dietlein M, Guermazi A, et al. Use of positron emission tomography for response assessment of lymphoma: Consensus of the Imaging Subcommittee of International Harmonization Project in Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:571–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Metser U, Goor O, Lerman H, Naparstek E, Even-Sapir E. PET-CT of extranodal lymphoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1579–86. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.6.1821579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guermazi A, Brice P, de Kerviler EE, Fermé C, Hennequin C, Meignin V, et al. Extranodal Hodgkin disease: Spectrum of disease. Radiographics. 2001;21:161–79. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.1.g01ja02161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dodd GD, Greenler DP, Confer SR. Thoracic and abdominal manifestations of lymphoma occurring in the immunocompromised patient. Radiol Clin North Am. 1992;30:597–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nyberg DA, Jeffrey RB, Federle MP, Bottles K, Abrams DI. AIDS-related lymphomas: Evaluation by abdominal CT. Radiology. 1986;159:59–63. doi: 10.1148/radiology.159.1.3952331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee WK, Lau EW, Duddalwar VA, Stanley AJ, Ho YY. Abdominal Manifestations of Extranodal Lymphoma: Spectrum of Imaging Findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:198–206. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Pantongrag-Brown L, Buck JL, Herlinger H. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: Radiographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:165–72. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.1.8976941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Haddad G, Alavi A, Mavi A, Bural G, Zhuang H. Normal variants in 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET imaging. Radiol Clin N Am. 2004;42:1063–81. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tatlidil R, Jadavar H, Bading JR, Conti PS. Incidental colonic fluorodeoxyglucose uptaske: Correlation with colonoscopic and histopathologic findings. Radiology. 2002;224:783–7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2243011214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boellaard R, O’Doherty MJ, Weber WA, Mottaghy FM, Lonsdale MN, Stroobants SG, et al. FDG PET and PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour PET imaging: Version 1.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:181–200. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1297-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lynch MA, Cho KC, Jeffrey RB, Alterman DD, Federle MP. CT of peritoneal lymphomatosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151:713–5. doi: 10.2214/ajr.151.4.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martinez S, Mc Adams HP, Erasmus JJ. Mediastinum. In: Haaga JR, Dogra VS, Forsting M, Gilkeson RC, Ha HK, Sundaram M, editors. CT and MRI of the whole body. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2009. pp. 969–1036. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee KS, Kim Y, Primack SL. Imaging of pulmonary lymphomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:339–45. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.2.9016202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strauss LG. Sensitivity and specificity of positron emission tomography (PET) for the diagnosis of lymph node metastasis. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2000;157:12–9. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-57151-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jack CR, O’Neill BP, Banks PM, Reese DF. Central nervous system lymphoma: Histological types and CT appearance. Radiology. 1988;167:211–5. doi: 10.1148/radiology.167.1.3279454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoffman JM, Waskin HA, Schifter T, Hanson MW, Gray L, Rosenfeld S, et al. FDG-PET in differentiating Lymphoma from nonmalignant central nervous system lesions in patients with AIDS. J Nucl Med. 1993;34:567–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bragg DG. Lymphoproliferative neoplasms. In: Bragg DG, Rubin P, Hricak H, editors. Oncologic imaging. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2002. pp. 853–83. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rizvi MA, Evens AM, Tallman MS, Nelson BP, Rosen ST. T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2006;107:1255–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsai EY, Taur A, Espinosa L, Quon A, Johnson D, Dick S, et al. Staging accuracy in mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome using integrated positron emission tomography and computed tomography. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:577–84. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delbeke D, Coleman RE, Guiberteau MJ, Brown ML, Royal HD, Siegel BA, et al. Procedure guideline for tumor imaging with 18 F-FDG PET/CT 1.0. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:885–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar R, Halanaik D, Malhotra A. Clinical applications of positron emission tomography-computed tomography in oncology. Indian J Cancer. 2010;47:100–19. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.62997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lustberg MB, Aras O, Meisenberg BR. FDG PET/CT findings in acute adult mononucleosis mimicking malignant lymphoma. Eur J Haematol. 2008;81:154–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2008.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Castellucci P, Nanni C, Farsad M, Alinari L, Zinzani P, Stefoni V, et al. Potential pitfalls of 18F-FDG PET in a large series of patients treated for malignant lymphoma: Prevalence and scan interpretation. Nucl Med Commun. 2005;26:689–94. doi: 10.1097/01.mnm.0000171781.11027.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perry C, Herishanu Y, Metzer U, Bairey O, Ruchlemer R, Trejo L, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of PET/CT in patients with extranodal marginal zone MALT lymphoma. Eur J Haematol. 2007;79:205–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]