Abstract

Ultrasonography (USG) is an accepted and reliable tool for the assessment of groin hernias. However, USG of the groin is operator dependent and challenging. The anatomy of this region is complex and the normal sonographic findings can be difficult to interpret. We describe the relevant normal anatomy of the groin relating to inguinal and femoral hernias, and describe a straightforward, reliable technique for identifying and assessing the integrity of the inguinal and femoral canals. The inferior epigastric vessels are a critical landmark for assessment of the inguinal canal and deep inguinal ring.

Keywords: Inguinal, technique, ultrasound

Introduction

A hernia is defined as a protrusion of a structure through a wall that normally contains it. There are several types of abdominal wall hernias, which are most commonly inguinal.[1] These are associated with symptoms of discomfort and pain, as well as the surgical complications of incarceration, bowel obstruction, and strangulation.[2] Clinical examination is the gold standard for diagnosing a groin hernia, and where there are clear clinical features, no further investigation is required. In equivocal cases, USG is increasingly used as a confirmatory modality, with high sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing groin hernias.[3] It is a dynamic, non-invasive tool, which does not use ionizing radiation, unlike herniography and computed tomography (CT) scanning. However, USG has the limitation of operator dependence, and training in groin ultrasound scanning is anecdotally non-uniform.

The three-dimensional anatomy of the inguinal canal is conceptually difficult to understand, and the femoral canal less so.[4] A detailed knowledge of the various components of the walls of the inguinal canal, conjoint tendon, and the neurovascular components of the spermatic cord is of interest, but not essential for identifying inguinal or femoral hernias on USG. However, a basic awareness of the anatomy of these regions is essential for competent diagnostic USG of the groin, especially to confirm structural integrity of the anterior abdominal wall and inguinal canal. In this brief review, we aim to provide the necessary anatomical detail relevant to scanning the groin for hernias, and relate this to an easily reproducible sonographic approach of examining the inguinal and femoral canals.

Anatomy

From superficial to deep, the anterior abdominal wall is composed of skin, subcutaneous fat, muscle/aponeuroses, fascia, and peritoneum. Lying either side of the midline are the rectus abdominis muscles, separated by the linea alba. More laterally, there are three layers of flat muscles, the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis. At their medial aspect, these form flat broad tendons (aponeuroses), which run toward and then superficial or deep to the rectus abdominis. The inguinal ligament is the thickened, rolled-up inferior edge of the external oblique aponeurosis, running from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle.

The inguinal canal lies just superior to the medial half of the inguinal ligament. It is a short oblique tunnel running through the anterior abdominal wall [Figure 1]. Consequently, the walls are primarily formed from the aponeuroses of the anterior abdominal wall muscles. The inguinal canal transmits the spermatic cord and ilioinguinal nerve in males, and the round ligament of the uterus and ilioinguinal nerve in females. There are two openings: The deep and superficial inguinal rings. The superficial ring is an opening in the external oblique aponeurosis, lying above and medial to the pubic tubercle. The deep ring is a defect in the transversalis fascia, lying above the midpoint of the inguinal ligament. Indirect inguinal hernias pass through the deep inguinal ring, down through the canal toward the superficial ring. Direct hernias are acquired and pass through a weakened abdominal wall medial and inferior to the deep ring.

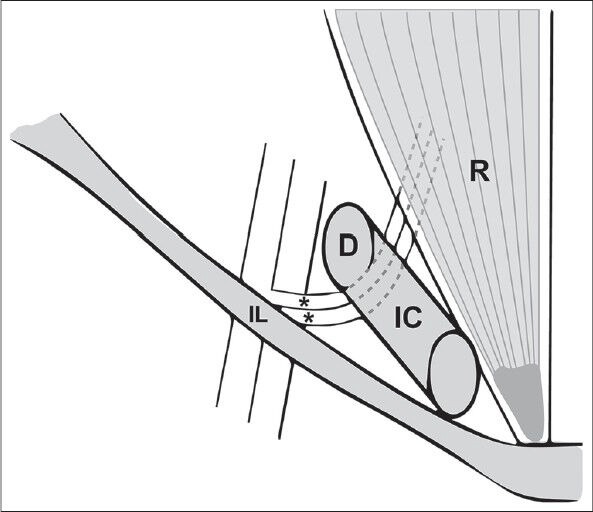

Figure 1.

Simplified illustration of the course of the right inferior epigastric vessels (asterisks), indicating their relationship medial to the edge of the deep inguinal ring (D). From their origin at the external iliac vessels just above the inguinal ligament (IL), they travel from deep to superficial, passing behind the inguinal canal (IC), to pierce the posterior rectus abdominis (R)

The inferior epigastric vessels are a critical landmark for sonographic assessment of the groin. They originate from the external iliac artery and vein immediately above the inguinal ligament. There are usually three vessels running together, two veins and an artery. They pass anteromedially, piercing the back of the anterior abdominal wall, then running upward on the posterior aspect of the rectus abdominis, which it eventually pierces and supplies [Figure 1]. This level is known as the arcuate line; below this level, the posterior rectus sheath is deficient. During the course of its ascent toward the rectus muscle, the inferior epigastric vessels pass behind the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, at the medial boundary of the deep inguinal ring. This facilitates the differentiation of direct and indirect inguinal hernias on USG.[2]

The anatomy of the femoral canal is conceptually easier to understand than the inguinal region. The femoral canal lies just below the inguinal ligament and lateral to the pubic tubercle. Consequently, a femoral hernia will pass below and lateral to the pubic tubercle, whereas an inguinal hernia will be seen above and medial to it. The key landmark for the femoral canal is the femoral vein. This lies immediately lateral to the femoral canal, with the femoral artery lateral to the vein. It normally contains only a lymph node, connective tissue, and fat. The saphenofemoral junction lies at the inferior aspect of the femoral canal and is a useful sonographic landmark. When present, a femoral hernia enters the canal through the femoral ring superiorly, compressing the medial aspect of the femoral vein, reducing its caliber. This is seen more reliably with an increase in intra-abdominal pressure, where the femoral vein distends in the absence of a hernia.

USG Technique

Our approach is centered on the inferior epigastric vessels, which are followed in a transverse plane from within the rectus abdominis down the lower abdomen, toward their origin in the external iliac artery. The inguinal and femoral canals are superficial, non-rigid, and small in caliber. We would, therefore, recommend a high-frequency 12-MHz linear transducer, light probe pressure, and slow, controlled movements of the transducer during an examination to maintain anatomical perspective. The normal inguinal canal becomes difficult to visualize with excessive compression. The use of controlled Valsalva maneuvers, with split/dual screen before and after comprassion images is essential. We favor using controlled instructions such as “blow out your cheeks with your mouth closed,” “tense up your stomach,” or “raise your head from the pillow” rather than coughing, which is less controlled. We would also advocate repeating the examination with the patient standing if initial findings are negative.

We summarize the stages in our technique below:

The patient is asked to point to the location of their symptoms and is briefly examined for a palpable mass

The probe is orientated in a transverse plane over the rectus abdominis, just below the umbilicus in order to locate the deep inferior epigastric vessels within the rectus abdominis [Figure 2]

As the probe is moved inferiorly, the deep inferior epigastric vessels pass from medial to lateral and superficial to deep toward their origin at the external iliac vessels. Keeping the image centered on the inferior epigastric vessels, a surrounding soft tissue bulge gradually becomes apparent deep and lateral to the posterior aspect of the rectus abdominis [Figure 3]. This is the superior aspect of the inguinal canal. This is easier to visualize in males, in whom the heterogeneous tubular structures of the spermatic cord and surrounding echogenic fat are prominent. These are of course absent in females [Figure 4]

The probe is now orientated slightly obliquely along the long axis of the inguinal ligament, which has a similar orientation to the inguinal canal. This enables the demonstration of a long axis view of the inguinal canal [Figure 5]

As the probe is moved slightly more inferiorly, the deep inguinal ring is seen as a hypoechoic defect in the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, just lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels [Figure 6]. If this is difficult to localize, small craniocaudal movements of the probe over this region will demonstrate the contents of the cord entering the deep ring

This is the perfect location to assess for the presence of an indirect inguinal hernia. A controlled Valsalva maneuver is performed, keeping the deep ring within view and the inferior epigastric vessels at the center of the image. An indirect hernia is seen as a bulge emerging from the deep ring, passing over the inferior epigastric vessels, and moving down the inguinal canal toward the superficial ring [Figure 7]

To assess for the presence of a direct hernia, the probe is moved slightly inferior and medial to the deep ring, but above the pubic tubercle. Another Valsalva maneuver is performed. A direct hernia is seen as a “ballooning” of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal [Figure 8]

Moving below the inguinal ligament, the femoral artery and vein are located in a transverse plane. The saphenofemoral junction is visualized and this landmark used to assess for a femoral hernia [Figure 9]. The probe is moved slightly superior to this level, as a femoral hernia will not be seen below the junction. A controlled Valsalva maneuver is performed, normally resulting in distension of the femoral vein with increased intra-abdominal pressure. In contrast, a femoral hernia descends from above, causing a soft tissue bulge medial to the femoral vein, which is compressed [Figure 10]. For clarification, a further longitudinal section centered just medial to the femoral vein allows good visualization of the normal peritoneal reflection [Figure 11] superior to the femoral canal. This will be seen to descend into the femoral canal with a hernia

Examine the soft tissues of the groin for evidence of soft tissue or vascular abnormality such as lymphadenopathy, abscess, or aneurysm

In the absence of any hernia, repeat the examination with the patient standing

In a radiological report, always note the reducibility of the hernial sac and its contents (omental fat, bowel).

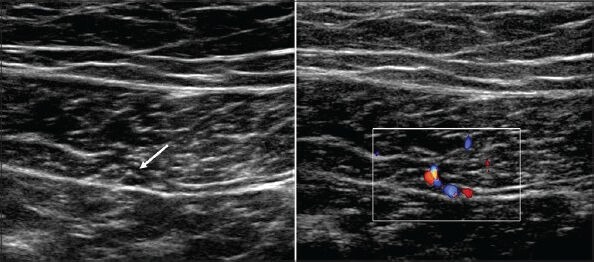

Figure 2.

Transverse USG image over the right rectus abdominis just below the umbilicus showing the inferior epigastric vessels (arrow) within the substance of the posterior muscle. Color Doppler may be used to locate the vessels if not immediately apparent

Figure 3.

Transverse USG image. The inferior epigastric vessels have emerged from the right rectus abdominis and are traveling posterolaterally toward their origin. A soft tissue bulge (arrowheads) is seen deep to the rectus, representing the superior aspect of the inguinal canal

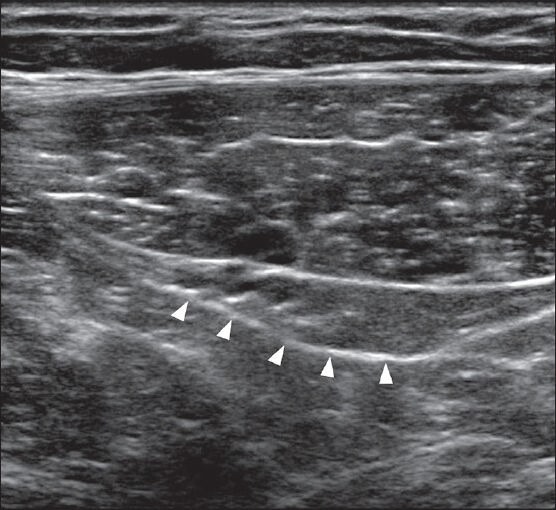

Figure 4.

The inguinal canal is less prominent in the female due to the absence of the spermatic cord

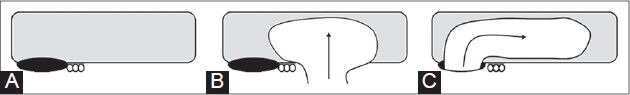

Figure 5 (A-C).

Simplified diagram of a long axis view through the right inguinal canal. The deep inferior epigastric vessels (three circles) lie at the medial aspect of the deep inguinal ring (black oval) (A). Direct inguinal hernias originate medially to the inferior epigastric vessels (B) and indirect inguinal hernias pass through the deep ring laterally and then over the inferior epigastric vessels (C)

Figure 6.

This is a long axis view through the right inguinal canal, inferior to Figure 3, oriented parallel to the inguinal ligament. The deep inguinal ring (arrowheads) is a hypoechoic defect in the posterior wall of the inguinal canal immediately lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels

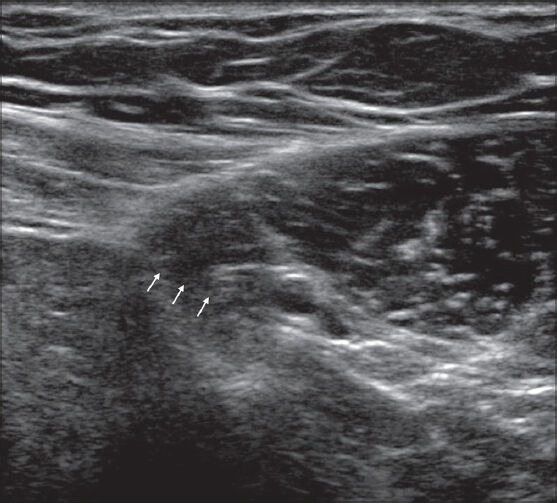

Figure 7.

Long axis USG image through the right inguinal canal. The indirect inguinal hernia (arrows) emerges lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels (IEV) through the deep ring (crosses), passing over the vessels and down the canal toward the superficial ring

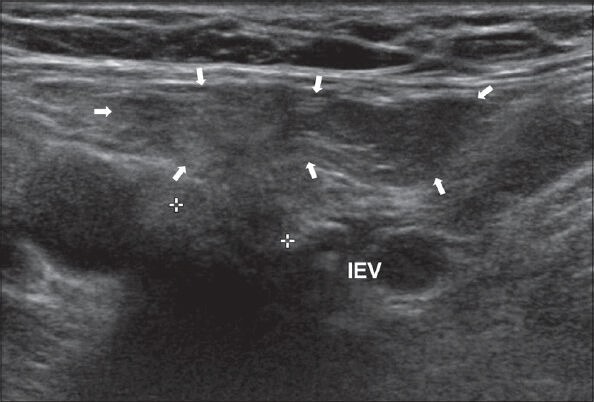

Figure 8.

Transverse USG image of a right direct inguinal hernia (arrows) arising medial to the inferior epigastric vessels (IEV) and deep ring

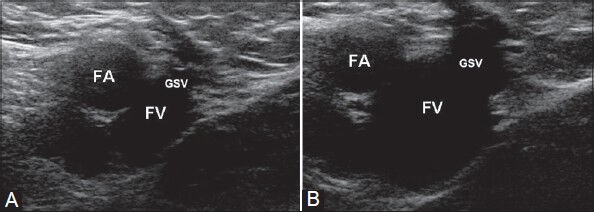

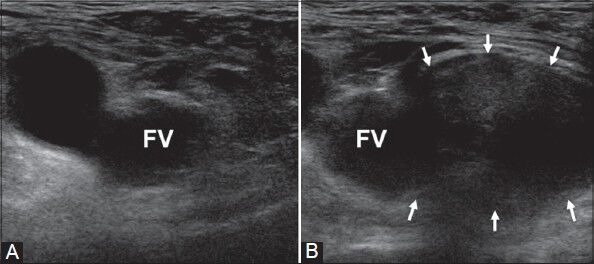

Figure 9 (A, B).

Transverse USG image of the right saphenofemoral junction, before (A) and during a Valsalva maneuver (B). The femoral vein (FV) distends when there is increased intra-abdominal pressure and no femoral hernia. This is the inferior margin of the femoral canal. FA = femoral artery; GSV = great saphenous vein

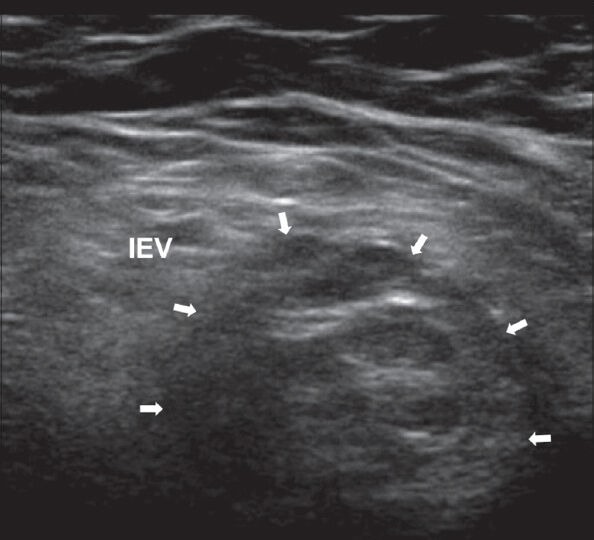

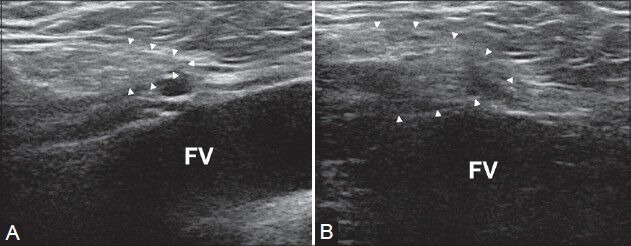

Figure 10 (A, B).

Transverse USG image demonstrating the typical right femoral hernia emerging medial to a compressed femoral vein (FV) with increased intra-abdominal pressure. (A) was taken at rest and (B) during Valsalva

Figure 11 (A, B).

Longitudinal USG image through the femoral canal, above the saphenofemoral junction and slightly medial to the center of the femoral vein. The normal peritoneal reflection (dotted line) is seen superior to the femoral canal, limited by the femoral ring (A). In the absence of a hernia, this distorts, but the inferior margin remains in a similar location (B)

It is an accepted practice to examine the inguinal region by identifying the pubic tubercle or inferior epigastric vessels at their origin inferiorly, or by obtaining a short axis view of the inguinal canal, medial to the femoral vessels in a longitudinal plane.[5] However, the technique we have described is relatively straightforward to learn and is reproducible as a first-line assessment by radiologists in training, and less dependent on patient body habitus, with the inferior epigastric vessels reliably located within the rectus abdominis and followed inferiorly.

Conclusion

We have described a reliable and reproducible technique for sonographic assessment of groin hernias. In our experience, following the inferior epigastric vessels inferiorly in a transverse plane, as they emerge from the posterior rectus sheath, allows for reliable identification of the inguinal canal and deep inguinal ring in both males and females. The femoral vein at the saphenofemoral junction is the critical landmark for the femoral canal. The ability to confidently demonstrate normal inguinal and femoral anatomy on ultrasound is a valuable and clinically relevant skill. We hope that this description is a useful aid, especially for radiologists in training.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No.

References

- 1.Dabbas N, Adams K, Pearson K, Royle G. Frequency of abdominal wall hernias: Is classical teaching out of date? JRSM Short Rep. 2011;2:5. doi: 10.1258/shorts.2010.010071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rai S, Chandra SS, Smile SR. A study of the risk of strangulation and obstruction in groin hernias. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68:650–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1998.tb04837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley M, Morgan D, Pentlow B, Roe A. The groin hernia-an ultrasound diagnosis? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003;85:178–80. doi: 10.1308/003588403321661334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinnatamby CS. 12th ed. Edinburgh, New York: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2011. Last's anatomy: Regional and applied. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson P, Hensor E, Lansdown MJ, Ambrose NS, Chapman AH. Inguinofemoral hernia: Accuracy of sonography in patients with indeterminate clinical features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:1168–78. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]