Abstract

This paper examines how an adolescent's position relative to cohesive friendship groups in the school-wide social network is associated with alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use. We extend prior research in this area by refining the categories of group positions, using more extensive friendship information, applying newer analytic methods to identify friendship groups, and making strategic use of control variables to clarify the meaning of differences among group positions. We report secondary analyses of 6th through 9th grade data from the PROSPER study, which include approximately 9,500 adolescents each year from 27 school districts and 368 school grade cohort friendship networks. We find that core members of friendship groups were more likely to drink than isolates and liaisons, especially in light of their positive social integration in school, family, and religious contexts. Isolates were more likely to use cigarettes than core members, even controlling for all other factors. Finally, liaisons were more likely to use marijuana than core members.

Keywords: Substance use, Friendship groups, Adolescence

One of the core notions of social theory since Durkheim’s study of suicide in the late 1800s (Durkheim, 1997) is that integration into social groups is a fundamental determinant of psychological and behavioral health. A secure sense of social integration is a critical individual need from infancy throughout the life course (Bowlby, 1982). The issue of social integration beyond the family, and its implications for health-risking behaviors, is especially prominent during adolescence, as social bonds with peers become highly salient and youth develop increasing autonomy from parents. Indeed, research supports the view that the presence and quality of relations with friends in adolescence is a key influence on self-concept, feelings of depression, academic success, prosocial competence, and substance use (Greenberg, Siegel, and Leitch, 1983; Kobus, 2003; Wentzel and Caldwell, 1997).

The present paper focuses on the implications for the development of substance use of one dimension of adolescent peer relationships, namely, the peer group position occupied by an adolescents in the context of the friendship network in his or her school. Several studies suggest that adolescents’ positions in peer groups are linked to their risk for substance use (Ennett & Bauman, 1993; Fang, Li, & Stanton, 2003; Henry & Kobus, 2007; Kobus & Henry, 2010; Pearson, Sweeting, West, Young, Gordon, & Turner, 2006). Friendship ties are not random in the social networks of middle and high schools; factors such as similarity in attitudes, behaviors, ethnicity, and gender affect the likelihood that two individuals will be friends (Clark and Ayers, 1992; Urberg, Degirmencioglu, & Tolson, 1998). Furthermore, friendships are not distributed evenly. Instead, adolescent friendship networks show pronounced clumping or clustering, characteristic of distinct peer groups (Kreager, Rulison, & Moody, 2011), and adolescents greatly vary in total numbers of friends, ranging from very popular youths with many friends to those who are completely isolated (Moody, Brynildsen, Osgood, Feinberg, & Gest, 2011).

Friendship groups, sometimes informally referred to as cliques (Brown, 1990), represent a bounded set of friends. Members of a group presumably provide support to each other and communicate frequently, which provides the opportunity to influence each other’s attitudes and behaviors. From a social network perspective, groups are defined by the presence of relatively dense dyadic friendship ties within the set and sparse ties with individuals outside (See Moody & Coleman, 2014, Porter et al, 2009 for reviews). Members of the same group tend to be more homogenous than chance in terms of age, gender, race, social status, and/or interests and activities (Cohen, 1977; Coleman, 1961; Ennett & Bauman, 1996; Hollingshead, 1949; Shrum & Cheek, 1987).

Durkheim’s emphasis on social integration has led to two theoretical traditions that predict being a member of a cohesive group would reduce, on average, the likelihood of substance use. Social control theory (Hirschi, 1969; Jessor & Jessor, 1977) argues that bonds to such a group will promote conventionally acceptable behavior and dissuade people from behaviors that violate conventional norms, such as substance use. The second tradition would view group membership as providing a sense of social acceptance that minimizes the experience of strains that they might seek to alleviate through substance use (Merton, 1938; Agnew, 1992), consistent with self-medication explanations (Khantzian, 1997).

Some youths who are not part of friendship groups are relatively isolated and lack social integration (Cusick, 1973; Eder, 1985; Ennett & Bauman, 1993). Given the importance of social integration for well-being, these “isolates” may be expected to exhibit deviant or unhealthy attitudes and behaviors (Ennett & Bauman, 1993). Another important category of non-group members is youths who have friends, but who are difficult to assign to a single friendship group based on the pattern of their ties. These youth may appear to serve as “liaisons” bridging two groups (Ennett & Bauman, 1993). Sometimes these youth are conceptualized as experiencing elevated stress by their need to reconcile the demands of belonging to different groups; at other times, scholars have viewed these individuals as relatively healthy in demonstrating a capacity for flexible social integration. Liaisons are potentially important as they represent potential diffusion agents in the transmission of attitudes and behaviors from one friendship group to another (Ennett & Baumann, 1996).

Prior research has concentrated on differences in substance use among occupants of these three positions: group members, isolates, and liaisons (e.g., see Ennett & Bauman, 1996; Kobus & Henry, 2010). Ennett and Bauman (1993) found that smoking varied by social position, with isolates reporting higher rates of current smoking than the other categories. However, Henry & Kobus (2007) found instead that liaisons smoked more than isolates and members, and they proposed that the stressful nature of this network position might have caused increased use of tobacco.

At the same time that social integration is fundamental to health, being less integrated into a network might be healthier in some circumstances. For example, mothers in high-crime urban areas sometimes limit their children’s involvement with peers in an attempt to prevent their children’s exposure to and adoption of antisocial attitudes and behaviors (Furstenberg, Cook, Eccles, & Elder, 1999). Similarly, as substance use becomes more common in adolescence, integration into a social network would facilitate greater exposure to and opportunities for use. To the extent that substance use behaviors are transmitted through friendship networks, isolation could actually be protective against certain negative behaviors--even though such isolation may carry other burdens.

As prevention scientists consider both how to target interventions to those at risk, as well as how to leverage resources within the peer network to guide delivery of interventions (Valente, Hoffman, Ritt-Olson, Lichtman, & Johnson, 2003), an understanding of the relative risk levels of youth in different group positions within the friendship network may prove valuable. The few initial studies of differences in substance use between youth in these different group-related positions, while suggestive, are far from comprehensive. Most of the existing studies have involved small samples of individuals (e.g., Kobus & Henry, 2010; Pearson & Michell, 2000) or few networks (all previous studies), focused on only one form of substance use (e.g., Ennett & Bauman, 1993; Fang et al., 2003), and/or examined a very brief age span (e.g., Ennett & Bauman, 1993; Henry & Kobus, 2007; Pearson & Michell, 2000). Many of these studies likely mask the prevalence of friendship groups and group membership by allowing respondents to name few friends (Ennett & Bauman, 1993) or analyzing only reciprocated friendships (Henry & Kobus, 2007; Kobus & Henry, 2010; Pearson & Michell, 2000; Pearson et al., 2006). Some of the differences in findings among previous studies may also arise because they have used different sets of control variables, which alters the meanings of the relationships under investigation. At least one study assessed differences in substance use across the group positions without controlling for any other variables (Pearson & Michell, 2000), some have controlled only for demographic attributes such as gender and ethnicity (Ennett & Bauman, 1993; Henry & Kobus, 2007; Pearson et al., 2006), and others also control for peer substance use (Fang et al., 2003; Kobus & Henry, 2010). Only Kobus and Henry’s (2010) analysis of a small sample of 163 adolescents from a single school also controlled for any other relevant risk factors for substance use (e.g., school grades). Because of these weaknesses and variations, we do not have a clear understanding of how friendship group position is associated with the common substances of adolescent misuse: alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana.

The Current Study

In this paper, we examine the association of substance use with the types of positions adolescents hold in cohesive peer groups within the friendship networks of their schools’ grade-cohort. We conduct secondary analyses of data covering 6th through 9th grades, a period in which substance use begins to emerge at significant levels. We advance this line of research in several important ways.

Role position categories

First, we refine the traditional tripartite division of group positions (members, liaisons, and isolates) by adding two more categories and thereby sharpening the meanings of all the categories. Given the clear heterogeneity of involvement in friendship groups, it is possible that lumping together all group members overlooks within-group distinctions. First, we pursue Pearson and colleagues’ distinction between core and peripheral members, in which peripheral members represent an intermediate category between core group members and isolates. Like core members, peripheral members’ friendship ties distinctively link them to one group, which potentially enables them to experience a sense of belonging to a set of connected individuals. In contrast to the core members, however, the peripheral members’ have few friendship connections, so their overall social integration is more limited, approaching that of isolates. We differentiate peripheral group members from core members based on their embeddedness in the group, which we define by whether they are multiply versus singly connected to the group (Moody & White, 2003).

We reserve the term isolate for adolescents who are the least socially integrated in the senses that they have minimal friendships and that they totally lack friendship connections to any larger set of individuals, Thus, isolates are respondents with no friendship ties at all or only a single tie to one individual who has no other ties. We also refine the category of liaison to be more consistent with the notion of serving as an intermediary to multiple groups. We therefore limit this designation to individuals with direct friendship ties to at least two groups and exclude those whose ties to multiple groups are indirect (i.e., through others).

These definitions leave a residual category of individuals who are not members of any particular group and lack the connections to multiple groups that characterize liaisons. Yet they have multiple direct or indirect friendships with others and therefore do not qualify as isolates. This small residual category occupies a murky conceptual territory that is of limited interest in its own right. Nevertheless, we distinguish these youth as “other non-members” to maintain clear definitions of the positions of greater interest (e.g., peripheral group members, isolates, and liaisons).

Types of substance use

Second, we follow the lead of other recent studies of multiple forms of substance use (Henry & Kobus, 2007; Kobus & Henry, 2010; Pearson et al., 2006) and separately examine alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use. This comprehensive examination of the most common forms of early adolescent substance use has the potential to reveal insights into the ways different types of substance use are embedded in adolescent social structure. These substances each present important but different risks for health and safety, through distinct profiles of risks for long term disease, serious illicit drug use, and physical trauma. In addition, they differ in ways that imply distinct risk factors, such as ease of access, legality, rates of use, social context of use (e.g., parties, behind the school building), and perceived harm. These different characteristics may affect the ways social networks transmit and influence substance use, which could imply distinct strategies for preventing and reducing use.

Multiple models to address alternative explanations

Third, an important refinement provided by our analyses is that we control for important factors that are associated with adolescent substance use and represent alternative explanations of any relationship between friendship group position and substance use. As with previous research on this topic, our analyses are not intended to establish causal effects of group positions. Because friendship group position represents a snapshot of a continually evolving and highly endogenous social network, proving causality would be a tall order (Shalizi & Thomas, 2011). Instead, our goal is to clarify what differences exist and whether they are greater than would be expected based on various types of risk factors for substance use.

Our base model controls for variables we consider essential to establishing that differences between the friendship group positions are sufficiently distinct from other basic risk factors to be of interest. These begin with basic demographic factors, including family structure, family poverty, ethnicity, and gender. Perhaps the most important control variable is friends’ substance use. This is the key variable for both peer influence and the tendency to select similar friends, the most widely studied connections between friendship networks and substance use (e.g., Warr, 2002). Kreager and colleagues (2011) reported that groups with a high prevalence of alcohol use tend to be less well integrated, which suggests that some types of group positions may be associated with peers’ substance use. Thus, it is important to control for peer use to ensure that network position is not confounded with these conceptually distinct network processes.

In addition to this base model, we estimate two more models with additional sets of controls to help assess the distinct contributions of other variables of special interest. In the second model, we examine whether associations between position and use are accounted for by social integration in the major settings of adolescent life beyond the friendship network: school, family, and religious contexts. Comparing these first two models will indicate whether differences among the group positions reflect a broader profile of social integration across life in general, rather than integration specifically in the realm of friendships.

The third model is intended to distinguish between two aspects of social integration with peers that combine in the friendship group positions. Specifically, we ask whether the associations of friendship group positions with substance use is a simple reflection of the extensiveness of adolescents’ friendship connections to peers, versus indicating a special significance of whether those connections link them to cohesive peer groups. This model goes beyond the second model by adding three indicators of social integration that each reflects one type of linkage to others, and none of which concern distinct friendship groups. These include the number of friendship nominations an individual made (“out-degree”) and received (“indegree”), and the “reach” of an individual to others in the networks through pathways of ties. Because the group positions necessarily differ in numbers of friendship ties (such as peripheral vs. core members),1 adding these controls will be informative about whether connectedness alone accounts for differences among group positions in substance use. If not, then substance use also depends on whether friendship connections clearly align the individual with one cohesive group (core and peripheral members), multiple groups (liaisons), or no group (isolates and other nonmembers).

METHODS

Sample

Our data were collected as part of the larger PROSPER (Promoting School-Community-University Partnerships to Enhance Resilience) study, a place-randomized trial of a school-based substance use prevention approach (Spoth, Greenberg, Bierman, & Redmond, 2004; Spoth et al., 2007).2 The PROSPER partnership model entailed the formation of a prevention team led by a local university Cooperative Extension educator, and the team led the implementation of a family-based intervention in 6th grade and a school-based intervention in 7th grade. PROSPER’s sample consists of two cohorts (2002 and 2003) of all sixth grade students in 28 rural public school districts in Iowa and Pennsylvania (N=12,245). The study had two criteria for selecting school districts: (1) a total enrollment of 1,300 to 5,200 students and (b) at least 15% of the student population eligible for free or reduced-cost school lunches. The average population in these communities was 19,000 residents and the median household income was $37,000. The districts’ enrollments were at least 95% English-speaking, economically diverse (with an average of 29% of families eligible for free or reduced cost school lunches), and predominantly white (61%–96%). Students completed in-school surveys in the Fall of the 6th grade and each Spring of the 6th through 9th grades. The overall study response rate was high (87.2%); approximately 9,500 students responded at each wave.

Social networks are populations of interacting individuals, so studies of friendship group positions and adolescent substance use have universally investigated schools, which readily establish relevant populations. Unfortunately, prior studies have included too few schools to provide confidence that the correlates of group position hold across schools, perhaps greatly limiting the generalizability of findings from each study. Our research addresses this issue by including data for multiple grade cohorts from a relatively large sample of small school districts.

Measures

Friendship data

At the end of each questionnaire, students in 27 school districts3 responded to questions asking for the names of up to two best friends and five additional friends from their current grade and school. The research team then matched these names to class rosters provided by the schools. The two grade cohorts for each school assessed at five waves yielded 368 wave-specific friendship networks. Most (93.9%) respondents named friends, and we identified most (83.0%) of the named friends as fellow students. Only 1.9% of nominations plausibly matched multiple names on the rosters and thus could not be identified, and 0.4% were inappropriate choices (e.g., pop stars). The remaining 14.7% matched no name on the school grade rosters and presumably were not respondents’ grade-mates. This percentage of complete data is high relative to other network studies (e.g., the Add Health study), and recent work on missing data in networks suggests only minimal distortion from such moderate levels of missing data (Borgatti et al, 2006, Kossinets, 2006, Costenbader & Valente, 2003).

Given our interests in both substance use and friendship group involvement, we focus on respondents who completed the survey in at least one wave. Based on these broad criteria, our analytic sample includes 47,860 person-waves. Listwise deletion is used on a model-by-model basis to exclude cases missing on key model variables. For smoking, listwise deletion reduced our sample to 45,872 person-waves for our first model and 44,389 person-waves for our latter two models. For drinking, listwise deletion reduced our sample to 45,839 person-waves for our first model and 44,359 person-waves for subsequent models. Lastly, for marijuana use, listwise deletion reduced our sample to 45,787 person-waves for our first model and 44,320 person-waves for subsequent models.

Friendship group positions

Prior studies of friendship group positions and substance use have identified groups based on either reciprocated friendships or very few friendships per respondent, which we believe has risked misleading classifications of individuals’ positions. For instance, considering only the closest friendships in this fashion omits many additional and meaningful connections. Thus, an adolescent could be mistakenly classified as a liaison between two otherwise disconnected groups, which are actually one integrated group with many other non-reciprocal or somewhat lower priority ties between the two halves. Our procedures allowed more friendship choices and we identify groups using both reciprocated and non-reciprocated ties, yielding a high rate of membership in groups with an average size consistent with other research on adolescent peer relations.

We identified groups as linked clusters of friends using a variant of Moody’s CROWDs routine, which is similar in form to other algorithms designed to search for groups by maximizing modularity scores (Moody, 2001). The modularity score (Guimera & Amaral, 2005) is a weighted function of within-group compared to cross-group ties. A value of 1.0 is achieved if all ties fall within the group and zero ties between groups. We obtained starting values based on principal component analysis (see also Bagwell, Coie, Terry, and Lochman, 2000 and Gest et al., 2007), which yields a set of starting groups that are determined by the data values, rather than a pre-specified number determined by the investigator. The algorithm then evaluates whether reassigning each student to another group would improve the modularity score (similar to Frank, 1995). After each student’s assignment is adjusted, the algorithm checks whether the modularity score would be improved by either merging any groups or splitting any group into two. It then repeats the whole process until no new changes arise. Some randomness is involved in the process, and thus it is possible to get slightly different solutions with different repetitions (Kreager, Rulison, and Moody 2011).

Using this approach, we identified 818 mutually exclusive peer groups in the first wave, 819 in the second, 839 in the third, 914 in the fourth, and 910 in the fifth wave. Average group size varied somewhat, with an average of 9.72 group members in the first wave, 10.55 in the second, 11.43 in the third, 10.82 in the fourth, and 10.61 in the fifth wave. Our method compares favorably with other published methods, finding assignments with modularity scores as high as or higher than the alternative models in the vast majority of cases.4 While our method identified the largest modularity score in most networks, compared to other published alternatives for large-scale network analysis, our approach tended to identified slightly smaller groups (see Newman and Girvan, 2004). We view the average group size yielded by our approach as a better substantive match to the group processes we wish to study than the larger collectivities typically derived by other methods.

Isolates were individuals who did not send or receive friendship nominations to anyone else in the grade network or who shared ties with one person who was disconnected from the rest of the network (forming an isolated dyad), and thus were not considered to be part of a group. Group members were distinguished as core vs. peripheral members of the group. Peripheral members were not part of the groups’ largest “bicomponent,” meaning that removing a single friendship link would be sufficient to separate them from the main portion of the group. The remainder of the group (i.e., the largest bicomponent) constituted the core members who are more diversely connected, among whom norms and ideas can presumably circulate more freely (Moody & White 2003). Liaisons were non-group members who had ties to members of two or more groups. A residual category of “other non-members” consisted of students who were not defined as members of a group, a liaison, or an isolate. Students in this category typically had few friends, no more than one of whom was a group member. The statistical models represent the group positions through a set of dummy variables that contrast all other positions to core members. Core members greatly outnumber the other positions and therefore provide the most informative comparison and the great statistical power. Wald tests of the set of coefficients for the four dummy variables provide significance tests for overall differences among the five group positions.

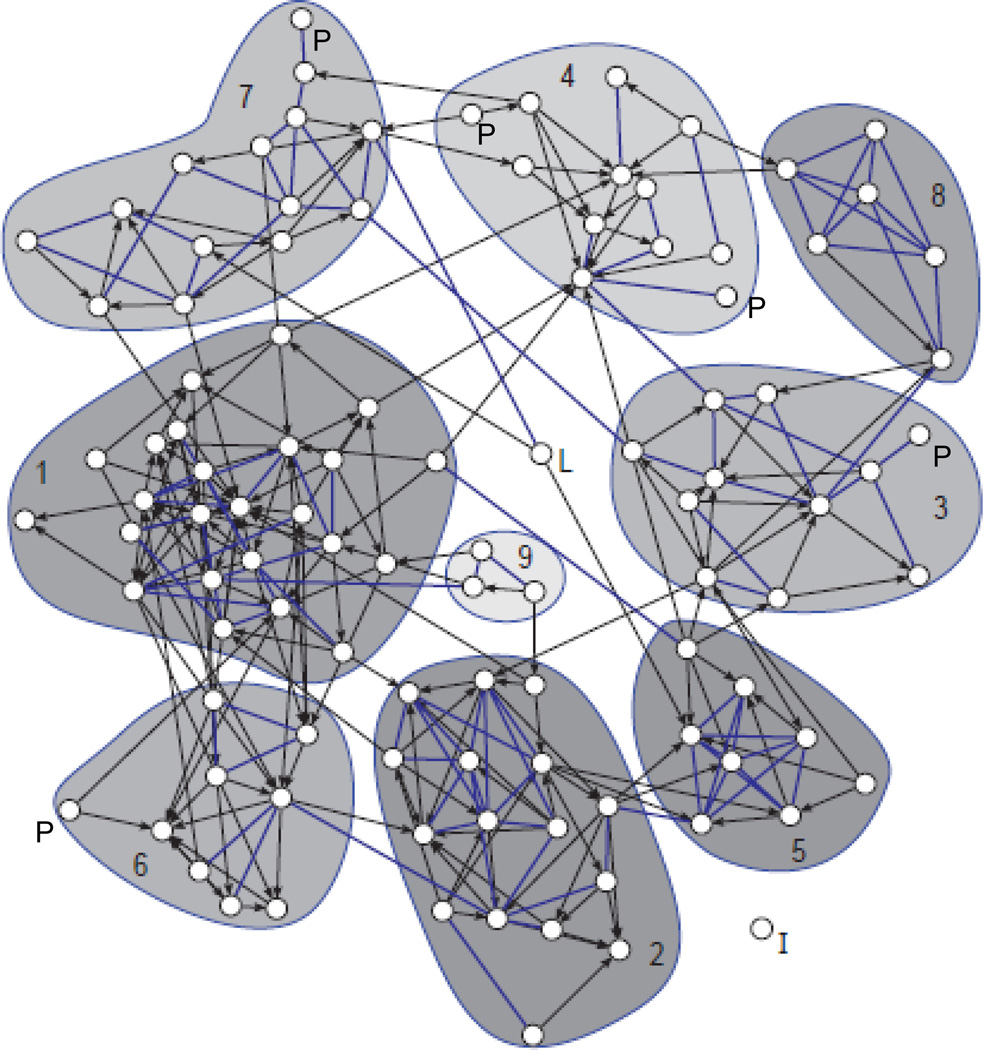

Figure 1 illustrates our grouping method with a sociogram of a single small PROSPER school. Nodes represent students, ties represent friendships (unreciprocated ties have arrows and reciprocated ties have no arrows), and shaded regions represent identified groups. All students are core group members except those labeled P, who are peripheral group members, student L, who is a liaison between groups 5 and 7, and student I, who is an isolate.

Figure 1.

Example of cohesive peer groups and positions relative to groups within a friendship network.

Substance use

The measure of drinking drives from the question, “During the past month, how many times have you had beer, wine, wine coolers, or other liquor?” Responses categories for all three substance use measures ranged from 1 = “Not at all” to 5 = “More than once a week.” Similarly, the measure of smoking comes from the question “During the past month, how many times have you smoked any cigarettes?” The measure for marijuana use is coded from the question “During the past month, how many times have you smoked any marijuana (pot, reefer, weed, blunts)?”

As Table 1 shows, rates of substance use were quite low at the beginning of the study, with fewer than ten percent reporting any use of each substance in fall of 6th grade, but the percentage of users rose at least four-fold by the spring of 9th grade. Given the low proportion of adolescents reporting each of the distinct frequencies of substance use (Table 1), we dichotomized measures of use to 0 = no past month use and 1 = any past month use.

Table 1.

Distributions of substance use measures

| Past Month Substance Use | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarettes | Alcohol | Marijuana | |

| Not at All | 90.7% | 79.7% | 95.1% |

| One Time | 3.0% | 10.4% | 1.7% |

| A Few Times | 2.6% | 7.2% | 1.4% |

| About Once a Week | 0.6% | 1.6% | 0.6% |

| More Than Once a Week | 3.1% | 1.1% | 1.2% |

| n | 46,054 | 46,017 | 45,966 |

| Reported Any Past Month Use | |||

| Cigarettes | Alcohol | Marijuana | |

| Wave 1, Fall of 6th Grade | 3.1% | 8.1% | 0.6% |

| Wave 2, Spring of 6th Grade | 4.6% | 11.4% | 1.3% |

| Wave 3, Spring of 7th Grade | 8.2% | 17.2% | 3.2% |

| Wave 4, Spring of 8th Grade | 12.3% | 26.2% | 6.9% |

| Wave 5, Spring of 9th Grade | 17.4% | 36.2% | 11.7% |

Control variables

The baseline model controls for demographic variables and some key features of our research design. Respondents’ sex is coded as 0 for female and 1 for males. Respondents reported on their race and ethnicity. White serves as the reference category, with dummy variables for the categories of Hispanic, Black, Native American, Asian, and other. Our measure of family structure is whether a student reported living with both biological parents, with a value of 1 indicating yes and 0 indicating some other living arrangement, such as living with a single parent or stepparent. Family poverty is reflected by students’ reports of whether (= 1) or not (= 0) they participated in a free or reduced price school lunch program. To capture mean changes in substance use over time in a flexible manner, the baseline model also uses a set of dummy variables to incorporate wave of data collection, with wave 1 serving as the reference category. The variable labeled “state” indicates in which of the two states a respondent resided. We include a dichotomous control for treatment condition indicating whether an individual attends a school that received the 6th and 7th grade substance use intervention programming (treatment condition =1) or not (control condition = 0). Such a control is necessary to insure that effects of the substance use intervention do not inadvertently distort results relevant to our research question. These analyses do not provide a meaningful test of the program effects, however, because they include pretest as well as posttest periods and control for other variables subject to influence from the program (e.g., friends’ substance use). Spoth and colleagues (2007, 2011) have reported PROSPER’s intervention effects based on analyses designed for that purpose.

The final two variables in the baseline model concern friends’ substance use. The first is the mean level of substance use among individuals either nominating the respondent as a friend or nominated by the respondent (based on the friends’ own self-report of use). This mean is calculated separately for each form of substance use. Because substance use is a dichotomous variable coded 0 versus 1 (the same as for the outcome measure), friends’ mean use is the proportion of friends reporting substance use. Respondents with no friendships were assigned the sample-wide mean value so that the coefficient for isolates would compare them to the group members with friends whose use if average. Preliminary analysis revealed a strong interaction between friends’ mean substance use and the number of friends in predicting respondent substance use, and we therefore included a product term for the interaction between them in the model as well. To insure that this interaction term did not alter the estimate of the relationship of substance use with number of friends, means were subtracted from both elements before forming the interaction term. A square root transformation was first applied to number of friends, which produced a better fit to the data. When the interaction term is based on the square root of the number of friends, the increment in slope per additional friend diminishes as the number of friends increases, which is consistent with the idea that adding a single friend is more consequential for people with fewer friends than for people with many friends.

Models 2 and 3 included five attitudinal and behavioral variables that reflect integration in non-peer contexts. School bonding is the mean of eight items that asked respondents to indicate their degree of agreement with statements regarding school attachment and adjustment (α = 0.81). These items include statements such as “I try hard at school,” “I get along well with my teachers,” and “Grades are very important to me.” Response options range from never true = 1 to always true = 5 (with some items reversed for logical consistency). High scores indicate positive adjustment and bonding. School Grades is a self-reported measure of the letter grades that the respondent usually receives, ranging from “mostly less than D’s” (scored as 1) to “mostly A’s” (scored as 5). Family Relations is the mean of five standardized subscales: affective quality, joint activities, monitoring, inductive reasoning, and cohesiveness (α = .81). Higher scores indicate more positive affective quality, time spent in activities, monitoring, use of inductive reasoning, and family cohesion (range: −3.0 to 1.2). A separate measure of discipline consisted of five items assessing parents’ use of harsh and inconsistent disciplinary practices (α = 0.77). These items include “When my parents discipline me, the kind of discipline I get depends on their mood,” and “When I do something wrong, my parents lose their temper and yell at me.” Response choices ranged from always (1) to never (5). Higher scores indicate more harsh and inconsistent discipline. Religiosity is measured by a single item asking how often respondent attended religious services. The measure ranges from more than once per week (8) to never (1).

Model 3 included three indicators of students’ connectedness to the friendship network: Out-degree refers to the number of other students the respondent named as friends, while in-degree refers to the number of other students who named the respondent. The third measure, reach, expands the view to also include friends of friends as well as friends themselves, counting both incoming and outgoing friendship choices. This measure is the count all students within two friendship ties of the respondent.

Analytic Strategy

We analyze our data with a three level, multi-level logistic regression model (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) that treats the five waves of data (level 1) as nested within individual respondents (level 2), who are in nested within the school district cohorts that define the social networks (level 3). This analytic approach addresses the dependencies among cases that arise from the hierarchical structure of the research design. Analyses include residual variance components for random intercepts at level 2, which capture stable individual differences in substance use, and at level 3, which capture unexplained differences among social networks in rates of substance use. Controlling for friends’ delinquency allows for any unexplained similarity among friends in the outcome measure, which would otherwise be an additional source of dependence in this network dataset.5 We conducted our analyses with HLM 6.08, and we report population average estimates with robust standard errors. Although these data are longitudinal, our interest in association rather than causal effects leads us to analyze them as pooled cross-sections, with explanatory variables and outcomes drawn from the same wave.

RESULTS

Descriptive Findings

Descriptive findings for our sample are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Table 2 indicates that, as expected, most respondents are core members in a friendship group (77.5%), although a moderate percentage of youth (15.4%) are peripheral group members. About 3% of all respondents are isolates or liaisons. These findings are relatively consistent by race and ethnicity, although Native Americans are more and Whites less likely to be isolates or liaisons, and Native Americans are less and Whites more likely to be core group members. Females are more likely to be core group members and less likely to be socially isolated than males. Youth Though recently developed stochastic actor-based models for analyzing longitudinal network data (Snijders, Steglich, & Schweinberger, 2007; Steglich, Snijders, & Pearson, 2010) have considerable appeal, they are not currently amenable to our research questions. Applying this method would require a continual updating of respondents’ group positions as part of the continuous time simulations at the heart of the method, which would entail many thousands of repeated cluster analyses. receiving school lunch assistance (an indicator of poverty) as well as those not living with two biological parents are less likely to be core members and are more likely to be isolates or peripheral group members.

Table 2.

Distribution of students across friendship group positions

| Distribution of Sample on Demographic Characteristic |

Distribution of Positions within Demographic Category | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristic |

Isolate | Liaison | Non- Member |

Peripheral Member |

Core Member |

||

| Entire Sample | - | 3.5% | 2.7% | 0.8% | 15.4% | 77.5% | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 81.0% | 3.1% | 2.7% | 0.8% | 14.3% | 79.1% | |

| Hispanic | 6.4% | 5.8% | 2.3% | 1.0% | 22.2% | 68.7% | |

| Black | 3.1% | 4.8% | 3.0% | 0.9% | 23.3% | 68.1% | |

| Native American | 0.5% | 7.6% | 3.6% | 1.6% | 24.0% | 63.2% | |

| Asian | 1.2% | 4.6% | 2.2% | 1.2% | 18.7% | 73.3% | |

| Other ethnicity | 7.8% | 5.0% | 3.1% | 0.7% | 17.2% | 74.0% | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 51.5% | 1.9% | 2.6% | 0.6% | 12.1% | 82.8% | |

| Male | 48.5% | 5.2% | 2.8% | 1.0% | 18.9% | 72.0% | |

| Lives with Two Biological Parents | |||||||

| No | 22.8% | 5.0% | 2.7% | 1.1% | 18.6% | 72.7% | |

| Yes | 77.2% | 3.0% | 2.7% | 0.7% | 14.4% | 79.1% | |

| Free or Reduced Price School Lunch | |||||||

| No | 68.4% | 2.5% | 2.8% | 0.6% | 13.4% | 80.6% | |

| Yes | 28.7% | 5.9% | 2.4% | 1.2% | 19.9% | 70.6% | |

Table 3.

Means for whole sample on self-report scale scores, and test of differences by friendship group positions

| Scale measures | Means (SD) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Sample |

Isolate | Liaison | Non- Member |

Peripheral Member |

Core Member |

F-Value | |

| School Bonding | 3.78(0.77) | 3.55 (0.83)b,c,d,e | 3.79(0.75)a,d | 3.71(0.81)a,e | 3.65(0.81)a,b,e | 3.82(0.75)a,c,d | 118.22* |

| Grades | 4.05(0.91) | 3.65 (1.00)b,c,d,e | 4.04(0.90)a,c,d,e | 3.82(0.98)a,b,e | 3.8(0.96)a,b,e | 4.11(0.88)a,b,c,d | 271.36* |

| Family Relations | −0.01(0.50) | −0.10(0.55)b,d,e | −0.03(0.51)a | −0.03(0.52) | −0.06(0.53)a,e | 0.00(0.49)a,d | 38.19* |

| Consistent Discipline | 3.58(0.96) | 3.27(1.17)b,e | 3.59(0.95)a,d | 3.46(1.02)a,e | 3.45(1.03)a,b,e | 3.62(0.93)a,c,d | 92.08* |

| Religious Participation | 4.83(2.65) | 4.27(2.83)b,e | 4.71(2.68)a,d,e | 4.37(2.79)e | 4.40(2.74)b,e | 4.94(2.61)a,b,c,d | 88.55* |

Notes: Superscripts a, b, c, d, & e refer to isolates, liaisons, non-members, peripheral members, and core members, respectively. These superscripts denote that those in a particular group position (labeled at the top of the column) scored significantly differently on that measure than those in the group positions corresponding to the superscripts.

p < 0.001.

Table 3 presents comparisons among the friendship group positions on the measures of integration in non-peer contexts. We found significant differences across the group positions for self-report measures of school bonding, grades, family relations, discipline, and religious participation: Isolates reported lower scores on all of these measures, whereas core group members scored higher than all other group positions. Liaisons had higher levels of academic grades and religious participation than peripheral and non-members, but otherwise these three categories of youth did not differ statistically. Overall, these descriptive findings indicate substantial variation in group position membership for each of our control variables.

Associations with Substance Use

Alcohol Use

The results from Model 1 (see Table 4), which included the basic controls for demographic variables, peer substance use, and study design variables, indicated that network position was not a significant predictor of alcohol use. However, adding the attitudinal and behavioral control variables in Model 2 yielded significant differences among the positions, with isolates and peripheral members showing significantly less drinking than core members. In other words, these two positions’ relatively average rates of drinking are lower than would have been expected, relative to core members, based on their weak social integration at school, home, and religious institutions. Inclusion of the network variables describing degree of connectedness with others accounted for some of the significant associations of network position with substance use found in Model 2. The comparison of peripheral members with core members was no longer significant and the difference for isolates was weaker in Model 3 than in model 2. Thus, a large share of the differences that emerged after controlling for other types of integration could be accounted for by their limited friendship connections with peers.

Table 4.

Prediction of Dichotomous Past Month Alcohol Use

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | ||

| Intercept | −2.566** | 0.086 | 0.451** | 0.124 | 0.351** | 0.128 | |

| Friendship Group Position | |||||||

| Isolate | −0.072 | 0.047 | −0.295 ** | 0.044 | −0.116* | 0.051 | |

| Liaison | −0.042 | 0.064 | −0.081 | 0.069 | −0.108 | 0.069 | |

| Peripheral Member | 0.029 | 0.032 | −0.089** | 0.034 | 0.000 | 0.042 | |

| Non-Member | −0.082 | 0.115 | −0.164 | 0.134 | −0.048 | 0.133 | |

| Demographics and Research Design | |||||||

| Sex | 0.001 | 0.023 | −0.170 ** | 0.025 | −0.162** | 0.026 | |

| Hispanic | 0.152* | 0.062 | 0.171* | 0.071 | 0.187** | 0.073 | |

| Black | −0.357** | 0.102 | −0.321** | 0.108 | −0.320** | 0.104 | |

| Native American | 0.425* | 0.212 | 0.286 | 0.205 | 0.316 | 0.205 | |

| Asian | −0.680** | 0.176 | −0.755** | 0.171 | −0.731** | 0.171 | |

| Other Ethnicity | 0.273** | 0.047 | 0.152** | 0.046 | 0.146** | 0.046 | |

| Biological Parents | −0.323** | 0.030 | −0.099** | 0.034 | −0.109** | 0.035 | |

| School Lunch | −0.101** | 0.036 | −0.217** | 0.036 | −0.187** | 0.035 | |

| Wave 2 | 0.292** | 0.035 | 0.160** | 0.035 | 0.129** | 0.036 | |

| Wave 3 | 0.616** | 0.039 | 0.344** | 0.042 | 0.292** | 0.045 | |

| Wave 4 | 0.940** | 0.038 | 0.609** | 0.040 | 0.582** | 0.041 | |

| Wave 5 | 1.282** | 0.038 | 0.911** | 0.041 | 0.905** | 0.042 | |

| State | 0.084* | 0.041 | 0.082* | 0.039 | 0.061 | 0.040 | |

| Treatment Condition | −0.007 | 0.041 | 0.037 | 0.039 | 0.040 | 0.040 | |

| Friends’ Substance Use | |||||||

| Friends' Mean | 2.149** | 0.065 | 1.953** | 0.067 | 1.929** | 0.067 | |

| Friends’ Mean Use × # Friends | 1.061** | 0.068 | 1.072** | 0.081 | 0.972** | 0.080 | |

| Integration in Non-peer contexts | |||||||

| School Bonding | −0.520** | 0.024 | −0.521** | 0.024 | |||

| Grades | −0.070** | 0.016 | −0.082** | 0.016 | |||

| Family Relations | −0.579** | 0.033 | −0.576** | 0.033 | |||

| Discipline | −0.176** | 0.014 | −0.176** | 0.014 | |||

| Religiosity | −0.021** | 0.006 | −0.023** | 0.006 | |||

| Connectedness to Network | |||||||

| Out-degree | −0.023** | 0.007 | |||||

| In-degree | 0.036** | 0.006 | |||||

| Reach | 0.006** | 0.001 | |||||

| Group Position Diffs (Wald, 4 df) | 3.581 | 69.659** | 9.955* | ||||

| Level 1–2 Variance Component | 1.237** | 1.073** | 1.053** | ||||

| Level 3 Variance Component | 0.012** | 0.009** | 0.010** | ||||

| N | 45839 | 44359 | 44359 | ||||

Cigarette Use

In Model 1 (see Table 5), results indicate that youth in all other friendship group positions report more cigarette use than core members, which cannot be explained by demographic characteristics and their friends’ cigarette use. The difference for isolates is particularly strong, and the one for liaisons is a trend (p < .10). Adding controls for social integration in other settings in Model 2 reduces the magnitude of these differences, especially for the difference between isolates and core members (from b = .569 to b = .346) and between peripheral and core members (from b = .268 to b = .144). Thus, a substantial share of those differences is also associated with more limited integration in those other domains. Adding the measures of network connectedness in Model 3 reduces the magnitude further, with only the difference between for isolates and core members remaining significant in Model 3, and the overall test of differences among positions no longer significant. Thus, general connectedness to peers appears to account for much of the remaining variation in smoking across the group positions.

Table 5.

Prediction of Dichotomous Past Month Cigarette Use

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef | SE | ||

| Intercept | −3.621** | 0.087 | 0.517** | 0.148 | 0.635** | 0.147 | |

| Friendship Group Position | |||||||

| Isolate | 0.569 ** | 0.074 | 0.346** | 0.082 | 0.184* | 0.091 | |

| Liaison | 0.123+ | 0.067 | 0.136+ | 0.078 | 0.093 | 0.078 | |

| Peripheral Mem. | 0.268** | 0.039 | 0.144** | 0.042 | 0.036 | 0.048 | |

| Non-Member | 0.387** | 0.120 | 0.321+ | 0.171 | 0.228 | 0.173 | |

| Demographics and Research Design | |||||||

| Sex | −0.082 ** | 0.027 | −0.328** | 0.030 | −0.372** | 0.030 | |

| Hispanic | −0.090 | 0.056 | −0.073 | 0.065 | −0.094 | 0.066 | |

| Black | −0.252** | 0.087 | −0.133 | 0.091 | −0.149 | 0.092 | |

| Native American | 0.392+ | 0.201 | 0.288 | 0.216 | 0.278 | 0.217 | |

| Asian | −0.650** | 0.142 | −0.586** | 0.163 | −0.604** | 0.165 | |

| Other Ethnicity | 0.227** | 0.059 | 0.075 | 0.057 | 0.063 | 0.057 | |

| Biological Parents | −0.680** | 0.036 | −0.416** | 0.040 | −0.410** | 0.040 | |

| School Lunch | 0.198** | 0.030 | 0.072* | 0.032 | 0.075* | 0.032 | |

| Wave 2 | 0.298** | 0.044 | 0.114* | 0.057 | 0.131* | 0.058 | |

| Wave 3 | 0.709** | 0.051 | 0.338** | 0.066 | 0.356** | 0.066 | |

| Wave 4 | 0.933** | 0.055 | 0.496** | 0.066 | 0.518** | 0.066 | |

| Wave 5 | 1.252** | 0.047 | 0.750** | 0.058 | 0.763** | 0.058 | |

| State | 0.195** | 0.045 | 0.215** | 0.055 | 0.208** | 0.056 | |

| Treatment Condition | −0.042 | 0.044 | −0.020 | 0.057 | −0.019 | 0.057 | |

| Friend's Substance Use | |||||||

| Friends' Mean | 3.823** | 0.088 | 3.305** | 0.096 | 3.347** | 0.097 | |

| Friends’ Mean Use × # of Friends | 1.998** | 0.103 | 1.770** | 0.119 | 1.871** | 0.121 | |

| Integration in Non-peer Contexts | |||||||

| School Bonding | −0.595** | 0.028 | −0.587** | 0.028 | |||

| Grades | −0.309** | 0.021 | −0.298** | 0.021 | |||

| Family Relations | −0.592** | 0.039 | −0.583** | 0.038 | |||

| Discipline | −0.146** | 0.019 | −0.145** | 0.019 | |||

| Religiosity | −0.048** | 0.008 | −0.047** | 0.007 | |||

| Connectedness to Network | |||||||

| Out-degree | −0.098** | 0.011 | |||||

| In-degree | 0.011 | 0.008 | |||||

| Reach | 0.006** | 0.002 | |||||

| Group Position Diffs (Wald, 4 df) | 87.759** | 28.743** | 6.454 | ||||

| Level 1–2 Variance Component | 1.407* | 1.254 | 1.242 | ||||

| Level 3 Variance Component | 0.014** | 0.035** | 0.036** | ||||

| N | 45839 | 44389 | 44389 | ||||

Marijuana Use

As with cigarette smoking, Model 1 results in Table 6 indicate that, after taking demographic characteristics and peer use into account, all categories of youth report more marijuana use than core members, although the comparison for the other non-member category is a trend. The addition of controls for social integration in school, family, and religious organizations reduces differences of isolates, peripheral members, and non-member from core members by about a third, but not the contrast between liaisons and core members. Adding controls for connectedness to peers again further reduces all differences, except between liaisons and core members. Thus, the greater substance use of liaisons than core members appears distinctive to their unique position in relation to cohesive peer groups, rather than being associated with stronger or weaker integration with either peers or other major adolescent settings.

Table 6.

Prediction of Dichotomous Past Month Marijuana Use

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef | SE | ||

| Intercept | −4.776** | 0.089 | −1.076** | 0.170 | −0.940** | 0.167 | |

| Friendship Group Position | |||||||

| Isolate | 0.563 ** | 0.086 | 0.319** | 0.090 | 0.142 | 0.111 | |

| Liaison | 0.346** | 0.110 | 0.380** | 0.117 | 0.312** | 0.120 | |

| Peripheral Member | 0.368** | 0.050 | 0.236** | 0.056 | 0.112+ | 0.062 | |

| Non-Member | 0.363+ | 0.189 | 0.255 | 0.225 | 0.155 | 0.228 | |

| Demographics and Research Design | |||||||

| Sex | 0.206 ** | 0.038 | 0.052 | 0.041 | −0.003 | 0.040 | |

| Hispanic | 0.141+ | 0.083 | 0.224* | 0.090 | 0.192* | 0.091 | |

| Black | 0.075 | 0.127 | 0.296* | 0.148 | 0.274+ | 0.149 | |

| Native American | 0.347 | 0.294 | 0.222 | 0.302 | 0.222 | 0.302 | |

| Asian | −1.035** | 0.302 | −0.974** | 0.328 | −0.994** | 0.328 | |

| Other Ethnicity | 0.458** | 0.077 | 0.287** | 0.078 | 0.265** | 0.079 | |

| Biological Parents | −0.650** | 0.031 | −0.345** | 0.038 | −0.337** | 0.040 | |

| School Lunch | 0.076+ | 0.046 | −0.025 | 0.046 | −0.015 | 0.045 | |

| Wave 2 | 0.553** | 0.061 | 0.392** | 0.076 | 0.411** | 0.077 | |

| Wave 3 | 1.274** | 0.069 | 0.891** | 0.092 | 0.906** | 0.094 | |

| Wave 4 | 1.758** | 0.069 | 1.337** | 0.081 | 1.357** | 0.083 | |

| Wave 5 | 2.162** | 0.079 | 1.731** | 0.098 | 1.742** | 0.099 | |

| State | 0.128* | 0.053 | 0.105+ | 0.052 | 0.095+ | 0.053 | |

| Treatment Condition | −0.167** | 0.055 | −0.136* | 0.055 | −0.134* | 0.055 | |

| Friend's Substance Use | |||||||

| Friends' Mean Use | 4.270** | 0.119 | 3.671** | 0.124 | 3.763** | 0.125 | |

| Friends’ Mean Use × Number of Friends | 2.473** | 0.111 | 2.250** | 0.134 | 2.408** | 0.137 | |

| Integration in Non-peer Contexts | |||||||

| School Bonding | −0.636** | 0.035 | −0.627** | 0.035 | |||

| Grades | −0.207** | 0.017 | −0.193** | 0.017 | |||

| Family Relations | −0.701** | 0.058 | −0.688** | 0.057 | |||

| Discipline | −0.114** | 0.024 | −0.114** | 0.024 | |||

| Religiosity | −0.063** | 0.008 | −0.062** | 0.007 | |||

| Connectedness to Network | |||||||

| Out-degree | −0.125** | 0.012 | |||||

| In-degree | 0.013 | 0.010 | |||||

| Reach | 0.008** | 0.003 | |||||

| Group Position Diffs (Wald, 4 df) | 109.544** | 47.432** | 13.712** | ||||

| Level 1–2 Variance Component | 1.363 | 1.194 | 1.164 | ||||

| Level 3 Variance Component | 0.026** | 0.019** | 0.019** | ||||

| N | 45787 | 44320 | 44320 | ||||

Control Variables

Many of the significant relationships of the control variables to outcomes were consistent across types of substance use and across the three models. Mean friend use (both main effect and interaction with number of friends) was strongly and significantly associated with all forms of substance, regardless of the other variables in the models. Youth whose friends reported use were more likely to report use of each substance themselves, and this relationship was stronger for youth with more friends. Compared to white youth, the reference group in the models, Hispanic youth report more drinking and marijuana use; African American youth reported less drinking; and Asian youth reported less use of all three substances. Respondent sex was not consistently associated with drinking and marijuana use; but in the final, full model (Model 3), results indicated that girls reported more drinking than boys did. Girls were also more likely to report cigarette smoking across all three models. The statistically significant terms for wave of data collection indicate that substance use grew over time, as expected. Youth living with both biological parents reported less substance use; and youth reporting school lunch assistance reported more drinking and cigarette use. The intervention condition term was significant only for marijuana, showing the importance of controlling for this variable to insure that the prevention program did not distort our primary results. Analyses designed for assessing program effects demonstrate more widespread positive program effects on substance use (see Spoth et al., 2007, 2011).

The attitudinal and behavioral constructs entered in Models 2 and 3 were significantly related to use of all substances, with school adjustment, positive family factors, and religious participation associated with less use. Finally, of the network variables included in Model 3, Reach was associated with significantly more and Out-degree was associated with significantly less substance use; In-degree was only significantly associated with more alcohol use. We do not regard this pattern as readily interpretable, as these three measures are inherently highly related, both conceptually and empirically. We include them only to eliminate variance due to simple connectedness to the network and thereby determine how much of the relationship of group position to substance use is due to this source.

DISCUSSION

Through our secondary analysis of the PROSPER data, we examined the extent to which adolescents’ positions in relation to the cohesive groups of their schools’ peer networks are related to use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana. Various scholars have theorized that involvement in peer groups or isolation from them would be linked to substance use, and they have explored these connections in several previous studies (e.g., Ennett & Bauman, 1993; Kobus & Henry, 2010; Pearson et al., 2006). The PROSPER dataset allowed a unique opportunity to advance research on this issue given the large number of youth in 27 school districts surveyed across five waves in grades 6 through 9. Our rich network data and advanced group identification method enable us to provide an especially rich portrayal of the group structure of these friendship networks, and the large sample of networks supports greater generalizability of findings than previous studies.

We also go beyond previous studies by seeking to clarify the likely sources of relationships between friendship group positions and substance use through strategic use of sets of control variables in a series of three regression models. The base model limited attention to differences between group positions that are not attributable to demographic characteristics, influence from peers or selection of similar peers, and design features of the study. The next set of control variables captured differences in integration or adaptation in other key domains of adolescent life, specifically, school, family, and religious organizations. Our third model helps distinguishes between two key aspects of the group positions by controlling for simple connectedness to the friendship networks, which inherently differs among the positions, after which any remaining differences among the positions must be specific to their standing in relation to cohesive peer groups.

The different patterns of results for each substance were striking, highlighting the importance of separately considering these behaviors, each of which brings serious but quite different risks to health and safety. Stated in the most general way, our results suggest that core friendship group members drink more than isolates and peripheral members, isolates are most likely to smoke cigarettes, and liaisons are more likely to use marijuana. These differential results indicate that the uptake of substance use in adolescence is not simply dependent on a combination of individual tendencies towards risky behavior and the affordances social networks provide for access to substances. Instead, different substances are used and diffused differently, dependent in part on adolescents’ positions in the larger peer network. Thus, strategies to reduce use by addressing friendship patterns would need to differ, depending on the substance of interest.

For alcohol use, significant group position differences were not present in the first model but only emerged when the second model took into account adolescents’ integration in academic, family, and religious settings. Thus, core members use more than we would expect given their generally successful functioning in these other domains. These differences diminished in the third model, which controlled for numbers of friendship ties. Thus, it appears that the number of friendship ties is a salient distinction between the isolate and core member positions that is also linked to alcohol use, specifically because greater numbers of friends is associated with higher rates of drinking. This result is consistent with a general pattern that early adolescent alcohol use is integrated in social networks in a variety of ways. Moody and colleagues (2011) reported that generalized substance use (which most strongly reflected alcohol use) was positively associated with attracting more friendship nominations, and Kreager and colleagues (2011) found that cohesive peer groups’ mean alcohol use coincided with stronger group integration and higher group status, especially after taking into account measures of adjustment comparable to ours. Finally, in a study of dynamic network processes, Osgood, Ragan, and colleagues (2013) determined both that attracting many friendships raised the risk of alcohol use and that drinkers were more likely to be chosen as friends. These results point to a highly social nature of adolescent alcohol use; that is, alcohol appears to be the substance of choice for adolescent parties and socializing.

Results for cigarette use were quite different than for alcohol use, and they support and clarify Ennett and Bauman’s (1993) original finding of high rates of smoking among isolates, which was replicated by Fang and colleagues (2003) but contradicted by Henry and Kobus (2007; Kobus and Henry, 2010). All other positions showed at least some evidence of more cigarette use than core members in the first model. In model 2, significant differences from core members were in evidence for isolates and peripheral members, indicating that both smoke even more than would be expected from their somewhat weaker integration in other settings. Model 3 showed that much of that relationship could be explained by isolates’ and peripheral members’ limited friendship connections, and the remaining significant difference between isolates and core members also indicated at least some of difference was specific to isolates disconnection from cohesive groups.

Finally, results for marijuana were different again. Isolates, liaisons, and peripheral members all reported more use than core members according to results in the first model with the basic set of control variables. Adding the additional set of control variables reduced the magnitude of differences from core members for isolates and peripheral members in models 2 and 3, but adding the additional control variables did not alter the size of the difference for liaisons very much. Model 3 showed that the remaining differences of isolates and peripheral members from core members are associated with their more limited friendship connections, rather than specific to relationships with groups. However, the elevated level of marijuana use by liaisons appears to be specifically associated with their structural position bridging groups.

Henry and Kobus hypothesized that role strain due to liaisons’ position between groups leads to elevated use (2007; Kobus & Henry, 2010);6 however, such role strain might be expected to affect use of all substances. The more specific connection to marijuana use may be related to the illicit nature of the substance, which would make it more difficult for youth to access than alcohol or cigarettes (which are legal, but of course illegal for distribution or use by minors). Furthermore, where alcohol use is associated with attracting more friends (a significant positive coefficient in Table 4 for in-degree; see also Osgood, Ragan et al., 2013), marijuana use is not (small and non-significant coefficient for in-degree in Table 6). Thus, marijuana use is likely limited to small groups of marijuana-using peers, and we suspect that liaisons’ multiple group connections increase chances that they are linked to such a group, giving them exposure and access to this substance.

It may be that liaisons participate in different friendship groups because they participate in the different activities associated with different groups. For example, a liaison might both play sports and be in an academic club, leading to friendships across separate densely connected peer groups. In future work, it would be interesting to compare the level of use of these liaisons with that of members of groups where marijuana use is the norm. It may be that liaisons connected to such a group use marijuana less often given their additional group affiliations than members whose peer group culture is strictly centered on drug use. One might also hypothesize that the liaisons would use fewer other substances, as they may be less entrenched in a substance-using peer group culture.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

We believe that our work represents an important advance for this area of research through studying a large sample of both individuals and communities over the critical period of emergence of substance use and through strong methods for classifying positions relative to cohesive peer groups. We also see several promising directions for future research, both to address limitations and to explore additional topics worthy of attention. First, our sample is limited to small, non-affluent, majority white communities in two states, and it would be valuable to replicate these findings in other populations and settings. Next, these relationships should be investigated in middle to late adolescence, when dangerous substance use becomes more common. Our analytic approach has helped clarify the plausibility of key alternative explanations of differences in substance use among positions relative to groups, but we have not attempted to establish whether those positions have a causal influence. Doing so is a difficult task, but an appropriate next step in that direction would be to assess the longitudinal connection of current positions with future substance use.

Turning to additional research topics, a useful direction for future work would be to expand on our approach by integrating the classifications of group positions with analyses of attributes of groups, such as their size, structural features (e.g., cohesion), and mean characteristics of members (e.g., Kreager et al., 2011). A second direction is to examine trajectories of positions relative to groups and attributes of groups in order to determine how movement between groups affects substance use.

Implications for Prevention

We see our research as adding to the growing body of work on the value of a focus on social networks in efforts to prevent substance use. Valente (2010; 2012) has written extensively about the relevance of social network theory and research to public health, and Gest and colleagues (2011) systematically articulated the relevance to prevention of social network concepts and methods. Program evaluations have yielded evidence that network approaches can be an important component of effective prevention programs through means such as identifying influential peer leaders to deliver programs (Valente et al., 2003) or creating network change that would enhance the diffusion of program benefits (Osgood, Feinberg, et al., 2013).

The present results suggest another avenue by which a social network approach might enhance preventive interventions. Specifically, intervention strategies might be tailored for different youth depending on their network role. An example of this strategy would be to identify isolates or near-isolates and provide such youth with either increased exposure to effective tobacco prevention or increased opportunities to build positive social connections. Similarly, given the greater risk of alcohol use by more socially connected youth, a community might decide to provide more popular youth with enhanced alcohol prevention.

Alternatively, prevention strategies may be developed for specific substances based on the way different substances are utilized by different types of youth. Such approaches may tailor messaging to be particularly applicable to the differing concerns of either isolated or popular youth. The greater use of alcohol by the most socially connected youth implies that a strategy of addressing the social context and perhaps the perceived social benefits of alcohol use may be most important. For example, alcohol related prevention strategies may help youth examine the potential social disadvantages of early alcohol use, or provide replacement leisure activities and contexts for groups of youth. In contrast, assuming that cigarette smoking provides a means for isolated youth to cope with isolation, loneliness, and even depression, tobacco related prevention may focus on helping youth cope with those underlying problems in more healthy ways.

Highlights.

We model how an adolescent’s role in social groups is associated with substance use

We use data from the school-based PRODPER study

Core group members are more likely to drink than isolates and liaisons

Isolates are more likely to use cigarettes than core members

Liaisons are more likely to use marijuana than core members

Acknowledgements

Support for this research was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (RO1-DA108225) and the William T. Grant Foundation (8316). The research uses data from PROSPER, a project directed by R. L. Spoth and funded by grant RO1-DA013709 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors:

Osgood and Feinberg conceived and designed the research reported here. Each of these authors also wrote a major portion of the paper. Osgood designed the multi-level analyses needed to execute the design. Wallace executed these multilevel analyses and wrote significant portions of the methods and results sections of the paper. Moody designed and executed the group identification analyses and wrote a portion of the methods section. All authors edited and approved the final version of the paper.

Conflict of Interest:

There are no conflicts of interest for any of the authors.

For example, core group members must have degree >= 2, peripheral members have degree > 0, but usually 1 or 2. Isolates can have a single tie to another isolate, but they typically have degree 0.

One of the authors of the present manuscript was an investigator on the original PROSPER Study.

One district declined to participate in the network portion of the study.

The alternative methods compared were the Greedy Partitioning method of Clausette et al (2004) and the Girvan & Newman (2002) edge-betweenness method, as implemented in the R iGraph package. Unlike our method, these methods follow a standard practice of exhaustive and mutually exclusive assignment of nodes to groups, making it impossible to identify liaison positions. Thus our method retains the modularity maximization heuristic common in modern group search algorithms while maintaining the key substantive insight from earlier on youth networks (Ennett & Bauman, 1993) that recognizes the importance of such between-group positions.

Though recently developed stochastic actor-based models for analyzing longitudinal network data (Snijders, Steglich, & Schweinberger, 2007; Steglich, Snijders, & Pearson, 2010) have considerable appeal, they are not currently amenable to our research questions. Applying this method would require a continual updating of respondents’ group positions as part of the continuous time simulations at the heart of the method, which would entail many thousands of repeated cluster analyses.

Kobus and Henry (2007) found higher rates of tobacco and alcohol use for liaisons than members or isolates, but not higher rates of marijuana use in a sample of 1,119 sixth grade students from 14 schools. We suspect that their findings differ from ours due to a combination of a very low rate of marijuana use in the sixth grade and their much different definition of liaisons, which included 30.1% of their study versus 2.7% in ours. The high proportion of liaisons in their analysis presumably results from limiting respondents to only three friendship nominations, which identified far fewer respondents as group members: 43.3% members in their case and 77.5% core members in ours.

Contributor Information

D. Wayne Osgood, The Pennsylvania State University.

Mark E. Feinberg, The Pennsylvania State University

Lacey N. Wallace, The Pennsylvania State University

James Moody, Duke University.

REFERENCES

- Agnew R. Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology. 1992;30:47–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, Coie JD, Terry RA, Lochman JE. Peer clique participation and social status in preadolescence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly: Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2000;46:280–305. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti SP, Carley KM, Krackhardt D. Robustness of centrality measures under conditions of imperfect data. Social Networks. 2006;28:124–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1982;52:664–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB. Peer groups and peer cultures. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 171–196. [Google Scholar]

- Clark ML, Ayers M. Friendship similarity during early adolescence: gender and racial patterns. The Journal of Psychology. 1992;126:393–405. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1992.10543372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauset A, Newman MEJ, Moore C. Finding community structure in very large networks. Physical Review E. 2004;70:066111. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.066111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JM. Sources of peer group homogeneity. Sociology of Education. 1977;50:227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS. The adolescent society. New York: Free Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Costenbader E, Valente TW. The stability of centrality measures when networks are sampled. Social Networks. 2003;25:283–307. [Google Scholar]

- Cusick P. Inside high school. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E. In: Suicide. George Simpson, editor. Free Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Eder D. The cycle of popularity: Interpersonal relations among female adolescents. Sociology of Education. 1985;58:154–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE. Peer group structure and adolescent cigarette smoking: a social network analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1993;34:226–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE. Adolescent Social Networks School, Demographic, and Longitudinal Considerations. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1996;11:194–215. [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Li X, Stanton B, Dong Q. Social network positions and smoking experimentation among Chinese adolescents. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27:257–267. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.3.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank KA. Identifying cohesive subgroups. Social Networks. 1995;17:27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Cook TD, Eccles J, Elder GH. Managing to make it: Urban families and adolescent success. University of Chicago Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gest SD, Osgood DW, Feinberg M, Bierman KL, Moody J. Strengthening prevention program theories and evaluations: Contributions from social network analysis. Prevention Science. 2011;12:349–360. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0229-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Siegel JM, Leitch CJ. The nature and importance of attachment relationships to parents and peers during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1983;12:373–386. doi: 10.1007/BF02088721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimera R, Nunes Amaral LA. Functional cartography of complex metabolic networks. Nature. 2005;433:895–900. doi: 10.1038/nature03288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry DB, Kobus K. Early adolescent social networks and substance use. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2007;27:346–362. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi Travis. Causes of delinquency. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Elmtown's youth. New York: Wiley; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1997;4:231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobus K, Henry DB. Interplay of network position and peer substance use in early adolescent cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30:225–245. [Google Scholar]

- Kobus K. Peers and adolescent smoking. Addiction. 2003;98:37–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossinets G. Effects of missing data in social networks. Social Networks. 2006;28:247–268. [Google Scholar]

- Kreager DA, Rulison K, Moody J. Delinquency and the structure of adolescent peer groups. Criminology. 2011;49:95–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2010.00219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. Social structure and anomie. American Sociological Review. 1938;3:672–682. [Google Scholar]

- Moody J, Brynildsen WD, Osgood DW, Feinberg ME, Gest S. Popularity Trajectories and substance use in early adolescence. Social Networks. 2011;33:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody J, Coleman J. Clustering and cohesion in networks: Concepts and measures. International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2014 (forthcoming) [Google Scholar]

- Moody J, White DR. Structural cohesion and embeddedness: A hierarchical concept of social groups. American Sociological Review. 2003;68:103–127. [Google Scholar]

- Newman MEJ, Girvan M. Finding and evaluating community structure in networks. Physical Review E. 2004;69:026113. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.69.026113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, Feinberg ME, Gest SD, Moody J, Ragan DT, Spoth R, Mark Greenberg M, Redmond D. Network effects of PROSPER on the influence potential of prosocial versus antisocial youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53:174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, Ragan DT, Wallace L, Gest SD, Feinberg ME. Peers and the emergence of substance use: Influence and selection in adolescent friendship networks. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2013;23:500–512. doi: 10.1111/jora.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson M, Michell L. Smoke rings: social network analysis of friendship groups, smoking and drug-taking. Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy. 2000;7:21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson M, Sweeting H, West P, Young R, Gordon J, Turner K. Adolescent substance use in different social and peer contexts: A social network analysis. Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy. 2006;13:519–536. [Google Scholar]

- Porter MA, Onnela JP, Mucha PJ. Communities in networks. Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 2009;56:1082–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models. 2nd Edition. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shalizi CR, Thomas AC. Homophily and contagion are generically confounded in observational social network studies. Sociological Methods & Research. 2011;40:211–239. doi: 10.1177/0049124111404820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrum W, Cheek NH., Jr Social structure during the school years: Onset of the degrouping process. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:218–223. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Steglich CEG, Schweinberger M. Modeling the co-evolution of networks and behavior. In: van Montfort K, Oud J, Satorra A, editors. Longitudinal models in the behavioral and related sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2007. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C, Greenberg M, Clair S, Feinberg M. Substance-use outcomes at 18 months past baseline: The PROSPER community-university partnership trial. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2007;32:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Clair S, Shin C, Greenberg M, Feinberg M. Preventing substance misuse through community-university partnerships: randomized controlled trial outcomes 4½ years past baseline. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;40:440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steglich C, Snijders TAB, Pearson M. Dynamic networks and behavior: Separating selection from influence. Sociological Methodology. 2010;40:329–393. [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW. Network interventions. Science. 2012;337(6090):49–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1217330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW. Social networks and health: Models, methods, and applications. Oxford, UK: Oxford; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW, Hoffman BR, Ritt-Olson A, Lichtman K, Johnson CA. Effects of a social-network method for group assignment strategies on peer-led tobacco prevention programs in schools. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1837–1843. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urberg KA, Degirmencioglu SM, Tolson JM. Adolescent friendship selection and termination: The role of similarity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1998;15:703–710. [Google Scholar]

- Warr M. Companions in crime: The social aspects of criminal conduct. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]