Abstract

BACKGROUND

In the main Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial, digoxin reduced the risk of 30-day all-cause hospitalization in older systolic heart failure patients. However, this effect has not been studied in older diastolic heart failure patients.

METHODS

In the ancillary DIG trial, of the 988 patients with chronic heart failure and preserved (>45%) ejection fraction, 631 were ≥65 years (mean age, 73 years, 45% women, 12% nonwhites), of whom 311 received digoxin.

RESULTS

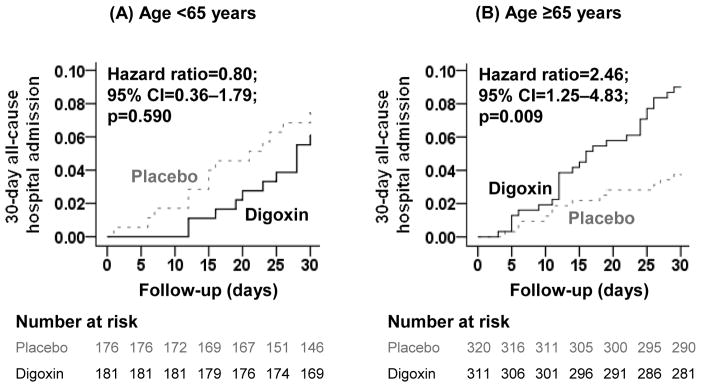

All-cause hospitalization 30-day post-randomization occurred in 4% of patients in the placebo group and 9% each among those in the digoxin group receiving 0.125 mg and ≥0.25 mg a day dosage (p=0.026). Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for digoxin use overall for 30-day, 3-month, and 12-month all-cause hospitalizations were 2.46 (1.25–4.83), 1.45 (0.96–2.20) and 1.14 (0.89–1.46), respectively. There was one 30-day death in the placebo group. Digoxin-associated HRs (95% CIs) for 30-day hospitalizations due to cardiovascular, heart failure and unstable angina causes were 2.82 (1.18–6.69), 0.51 (0.09–2.79), and 6.21 (0.75–51.62), respectively. Digoxin had no significant association with 30-day all-cause hospitalization among younger patients (6% vs. 7% for placebo; HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.36–1.79).

CONCLUSIONS

In older patients with chronic diastolic heart failure, digoxin increased the risk of 30-day all-cause hospital admission, but not during longer follow-up. Although chance finding due to small sample size is possible, these data suggest that unlike in systolic heart failure, digoxin may not reduce 30-day all-cause hospitalization in older diastolic heart failure patients.

Keywords: Digoxin, diastolic heart failure, 30-day all-cause hospital admission

Heart failure is the leading cause for hospital readmission for older Medicare beneficiaries.1 Despite limitations of the cost-driven metric of 30-day all-cause hospital readmission,2,3 nearly one in four hospitalized heart failure patients are readmitted within 30 days of index discharge.1 Hospital readmission accounts for up to 20% of Medicare cost for inpatient care and the reduction of Medicare cost is a priority under the Affordable Care Act, the new United States health care reform law.1 The law mandates financial penalties for hospitals with above-average readmission rates and heart failure is one of the three conditions for which the law is currently being implemented. In October, 2012, the Center of Medicare and Medicaid Services penalized over 2000 hospitals for the first time with $300 million in fine and this is projected to increase in the coming years.4 Post hoc analyses of the randomized controlled main Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial demonstrated that digoxin significantly reduced the risk of 30-day all-cause hospital admission in older patients with chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction or systolic heart failure without adversely affecting mortality or subsequent hospital admissions.5 However, the effect of digoxin on 30-day all-cause hospital admission in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction or diastolic heart failure remains unknown. The objective of the current study was to examine the effect of digoxin on 30 day all-cause hospital admission in older patients with diastolic heart failure in the ancillary DIG trial.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Patients

The DIG trial was a double-blind randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect of digoxin on mortality and hospitalization in 7788 ambulatory adults with chronic heart failure and normal sinus rhythm recruited from 186 U.S. centers and 116 Canadian centers between January 1991 and August 1993.6 Heart failure was diagnosed based on current or past history of symptoms, signs or radiographic evidence of pulmonary congestion and ejection fraction was estimated using radionuclide ventriculography (69%), transthoracic echocardiogram (26%) and contrast angiography (5%).6 Patients with ejection fraction ≤45% were enrolled in the main DIG trial (n=6800) and those with ejection fraction >45% were enrolled into the ancillary DIG trial (n=988).6,7

The current study focused on the 631 patients, aged ≥65 years enrolled in the ancillary DIG trial. Of these, 311 patients received digoxin, of which 90 received 0.125 mg a day and 221 received ≥0.25 mg a day. Data on serum digoxin concentration was collected after the first 30 days of randomization and was available for 118 of the 311 patients receiving digoxin, of which 68 had serum digoxin concentration of 0.5–0.9 ng/ml and 50 had serum digoxin concentration of ≥1.0 ng/ml. The DIG trial was sponsored by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, which also provided copies of de-identified data used in the current analysis.

Outcomes

The primary outcome in the ancillary trial was the occurrence of death due to progressive heart failure or hospitalization due to worsening heart failure. In the current analysis, hospitalization due to all-causes occurring during the first 30 days after randomization was the main outcome of interest. Secondary outcomes included cause-specific hospitalizations and mortality, and the combined end point of all-cause hospitalization or all-cause mortality during the first 30 days after randomization. All outcomes were classified by DIG investigators based on reviews of medical records and interviewing patients’ relatives.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline patient characteristics were compared between the two treatment groups using Pearson’s Chi-square and Student’s t tests. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the outcomes in the digoxin group using placebo group as the reference, and Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to plot 30-day all-cause hospitalization for patients in the digoxin and placebo groups. All analyses were repeated for patients <65 years. Subgroup analyses were conducted to examine heterogeneity of effect on outcomes only among older adults. All statistical tests were 2-tailed with a p-value <0.05 considered significant. SPSS-20 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) was used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

The subset of older patients ≥65 years (n=631) in the DIG ancillary study had a mean age of 73 (SD±6) years, a mean ejection fraction of 56% (SD±8), 45% were women, and 12% were nonwhite. These patients were well balanced in all baseline characteristics with regards to treatment assignment (Table 1). Younger patients were also balanced on nearly all baseline characteristics except for pulmonary râles and the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Younger and Older Patients With Chronic Heart Failure and Ejection Fraction >45% in the Ancillary Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) Trial, According to Randomization to Digoxin or Placebo

| Variables, mean (±standard deviation) or n (%) | Age <65 years | Age ≥65 years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Placebo (n=176) | Digoxin (n=181) | Placebo (n=320) | Digoxin (n=311) | |

| Age (years)** | 56 (±7) | 56 (±8) | 73 (±6) | 73 (±6) |

| Female** | 64 (36%) | 58 (32%) | 136 (43%) | 149 (48%) |

| Nonwhite** | 30 (17%) | 32 (18%) | 36 (11%) | 39 (13%) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)** | 30.1 (±7.1) | 30.0 (±7.4) | 27.8 (±5.5) | 27.7 (±5.2) |

| Duration of heart failure (months) | 28 (±33) | 26 (±29) | 29 (±38) | 24 (±30) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction** | 54 (±8) | 54 (±7) | 56 (±8) | 56 (±9) |

| Cardiothoracic ratio | 0.51 (±0.07) | 0.51 (±0.08) | 0.52 (±0.08) | 0.52 (±0.08) |

| Cardiothoracic ratio >55%** | 41 (23%) | 38 (21%) | 90 (28%) | 94 (30%) |

| New York Heart Association functional class** | ||||

| I | 40 (23%) | 43 (24%) | 62 (19%) | 51 (17%) |

| II | 106 (60%) | 114 (63%) | 176 (55%) | 177 (57%) |

| III | 30 (17%) | 23 (13%) | 74 (23%) | 79 (26%) |

| IV | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 8 (3%) | 3 (1%) |

| Signs or symptoms of heart failure | ||||

| Dyspnea at rest | 30 (17%) | 40 (22%) | 71 (22%) | 58 (19%) |

| Dyspnea on exertion | 130 (74%) | 122 (67%) | 242 (76%) | 228 (73%) |

| Jugular venous distension | 11 (6%) | 15 (8%) | 27 (8%) | 28 (9%) |

| Pulmonary râles** | 15 (9%) | 30 (17%)* | 63 (20%) | 47 (15%) |

| Lower extremity edema | 39 (22%) | 48 (27%) | 96 (30%) | 90 (29%) |

| Pulmonary congestion by chest x-ray | 18 (10%) | 18 (10%) | 34 (11%) | 31 (10%) |

| Number of signs or symptoms of heart failure† | ||||

| 0 | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| 1 | 5 (3%) | 1 (<1%) | 5 (2%) | 5 (2%) |

| 2 | 14 (8%) | 15 (8%) | 18 (6%) | 19 (6%) |

| 3 | 16 (9%) | 12 (7%) | 40 (13%) | 29 (9%) |

| 4 or more | 139 (79%) | 151 (83%) | 255 (80%) | 257 (83%) |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 92 (52%) | 94 (52%) | 153 (48%) | 150 (48%) |

| Current angina pectoris | 44 (25%) | 57 (32%) | 101 (32%) | 92 (30%) |

| Hypertension | 93 (53%) | 111 (61%) | 192 (60%) | 194 (62%) |

| Diabetes mellitus** | 64 (36%) | 54 (30%) | 86 (27%) | 81 (26%) |

| Chronic kidney disease** | 65 (37%) | 55 (30%) | 187 (58%) | 178 (57%) |

| Primary cause of heart failure** | ||||

| Ischemic | 103 (59%) | 104 (58%) | 177 (55%) | 173 (56%) |

| Hypertensive | 27 (15%) | 35 (19%) | 77 (24%) | 83 (27%) |

| Idiopathic | 24 (14%) | 29 (16%) | 29 (9%) | 22 (7%) |

| Others | 22 (13%) | 13 (7%) | 37 (12%) | 33 (11%) |

| Medications | ||||

| Pre–trial digoxin use | 68 (39%) | 60 (33%) | 112 (35%) | 108 (35%) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 160 (91%) | 153 (85%)* | 267 (83%) | 272 (88%) |

| Diuretics** | 131 (74%) | 128 (71%) | 251 (78%) | 241 (78%) |

| Nitrates | 64 (36%) | 66 (37%) | 129 (40%) | 130 (42%) |

| Heart rate (beats per minute)** | 78 (±13) | 76 (±13) | 76 (±12) | 75 (±11) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg)** | 133 (±22) | 136 (±21) | 138 (±21) | 140 (±21) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg)** | 78 (±11) | 79 (±12) | 76 (±11) | 76 (±12) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.20 (±0.35) | 1.19 (±0.38) | 1.29 (±0.40) | 1.27 (±0.39) |

| Daily dose of study medication, mg** | ||||

| ≤ 0.125 | 16 (9%) | 20 (11%) | 96 (30%) | 90 (29%) |

| 0.25 | 127 (72%) | 119 (66%) | 212 (66%) | 209 (67%) |

| ≥ 0.375 | 33 (19%) | 42 (23%) | 12 (4%) | 12 (4%) |

p<0.05 for differences between the two treatment groups.

p<0.05 for differences between the two age groups.

Clinical signs or symptoms included râles, elevated jugular venous pressure, peripheral edema, dyspnea at rest or on exertion, orthopnea, limitation of activity, S3 gallop, and radiologic evidence of pulmonary congestion present in past or present.

Digoxin and 30-Day All-Cause Hospital Admission

Among patients aged ≥65 years, the main endpoint of all-cause hospitalization during the first 30 days after randomization occurred in 3.8%, 8.9% and 9.0% of patients in the placebo group, and those in the digoxin group receiving 0.125 mg and ≥0.25 mg of digoxin a day, respectively (p=0.026). When compared with placebo, HR for 30-day all-cause admission for patients in the digoxin group as a whole was 2.46 (95% CI, 1.25–4.83; Table 2 and Figure 1). Among the 68 and 50 patients with 0.5–0.9 and ≥1 ng/ml serum digoxin concentrations, 30-day all-cause admission occurred in 5.9% and 4.0% of patients (vs. 3.8% in the placebo group; p=0.726).

Table 2.

Effect of Digoxin on Outcomes During 30 Days After Randomization Among Younger and Older Patients with Chronic Heart Failure and Ejection Fraction >45% in the Ancillary Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) Trial

| Outcomes | Age <65 years | Age ≥65 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Placebo (n=176) | Digoxin (n=181) | Hazard ratio† (95% CI) | Placebo (n=320) | Digoxin (n=311) | Hazard ratio† (95% CI) | |

|

|

|

|||||

| % (events) | % (events) | |||||

| Hospitalization | ||||||

| All-cause | 7.4% (13) | 6.1% (11) | 0.80 (0.36–1.79) | 3.8% (12) | 9.0% (28) | 2.46 (1.25–4.83) |

| Cardiovascular | 5.1% (9) | 3.3% (6) | 0.63 (0.23–1.78) | 2.0% (7) | 6.0% (19) | 2.82 (1.18–6.69) |

| Heart failure | 1.7% (3) | 0.6% (1) | 0.32 (0.03–3.09) | 1.3% (4) | 0.6% (2) | 0.51 (0.09–2.79) |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.6% (1) | 0.6% (1) | 0.98 (0.06–15.4) | 0.0% (0) | 1.0% (3) | —— |

| Unstable angina | 1.1% (2) | 0.6% (1) | 0.48 (0.04–5.32) | 0.3% (1) | 1.9% (6) | 6.21 (0.75–51.62) |

| Ventricular arrhythmia/cardiac arrest | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | —— | 0.0% (0) | 1.0% (3) | —— |

| Supraventricular arrhythmia | 1.1% (2) | 0.0% (0) | —— | 0.0% (0) | 0.6% (2) | —— |

| Suspected digoxin toxicity | 0.0% (0) | 0.6% (1) | —— | 0.0% (0) | 0.6% (2) | —— |

| Non–cardiovascular | 2.3% (4) | 2.8% (5) | 1.22 (0.33–4.53) | 1.6% (5) | 2.6% (8) | 1.66 (0.54–5.08) |

| Mortality | ||||||

| All-cause | 0.6% (1) | 0.0% (0) | —— | 0.3% (1) | 0.0% (0) | —— |

| Cardiovascular | 0.6% (1) | 0.0% (0) | —— | 0.3% (1) | 0.0% (0) | —— |

| Heart failure | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | —— | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | —— |

| All-cause hospitalization or All-cause mortality | 8.0% (14) | 6.1% (11) | 0.92 (0.42–2.03) | 4.1% (13) | 9.0% (28) | 2.27 (1.17–4.38) |

CI=confidence interval.

HRs comparing patients in the digoxin group with those in the placebo group.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier plots for 30-day all-cause hospital admission for ambulatory patients with chronic diastolic heart failure randomized to receive digoxin or placebo, stratified by age <65 years (A) and ≥65 years (B). The number of patients at risk at each 5-day interval after randomization is shown below the figure. CI= confidence interval.

This effect of digoxin was rather homogeneous across various subgroups of patients except by sex (Table 3). Compared to men in the placebo group, 4.9% of whom had 30-day all-cause hospitalization (reference), 4.9% of men in the digoxin group (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.39–2.61), 2.2% of women in the placebo group (HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.12–1.64), and 13.4% of women in the digoxin group (HR, 2.84; 95% CI, 1.29–6.23) had 30-day all-cause hospitalization (p for interaction, 0.019; Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of Digoxin on 30-Day All-Cause Hospital Admission in Subgroups of 631 Ambulatory Older Patients with Chronic Heart Failure and Ejection Fraction >45% in the Ancillary Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) Trial.

| Variable | Placebo | Digoxin | Hazard ratio† (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (event/total) | |||

| Age | |||

| ≤70 years (n=262) | 3.0% (4/135) | 7.9 %(10/127) | 2.71 (0.85–8.94) |

| >70 years (n=369) | 4.3% (8/185) | 9.8%(18/184) | 2.31 (1.01–5.32) |

| Sex | |||

| Male (n=346) | 4.9% (9/184) | 4.9% (8/162) | 1.01 (0.39–2.61) |

| Female (n=285) | 2.2% (3/136) | 13.4% (20/149) | 6.43 (1.91–21.64) |

| Non–white | |||

| No (n=556) | 3.9% (11/284) | 9.2% (25/272) | 2.43 (1.19–4.94) |

| Yes (n=75) | 2.8% (1/36) | 7.7% (3/39) | 2.78 (0.29–26.7) |

| Primary cause of heart failure | |||

| Non–ischemic (n=281) | 4.2% (6/143) | 8.7% (12/138) | 2.10 (0.79–5.59) |

| Ischemic (n=350) | 3.4% (6/177) | 9.2% (16/173) | 2.81 (1.10–7.18) |

| Chronic kidney disease | |||

| No (n=266) | 5.3% (7/133) | 8.3% (11/133) | 1.58 (0.61–4.09) |

| Yes (n=365) | 2.7% (5/187) | 9.6% (17/178) | 3.69 (1.36–10.02) |

| Pre-trial digoxin use | |||

| No (n= 411) | 3.4% (7/208) | 9.4% (19/203) | 2.85 (1.19–6.77) |

| Yes (n= 220) | 4.5% (5/112) | 8.3% (9/108) | 1.92 (0.64–5.71) |

| Ejection fraction | |||

| 45–54% (n= 328) | 3.7% (6/161) | 6.6% (11/167) | 1.78 (0.66–4.80) |

| ≥55% (n= 303) | 3.8% (6/159) | 11.8% (17/144) | 3.25 (1.28–8.25) |

| New York Heart Association functional class | |||

| I–II (n=467) | 2.1% (5/238) | 8.3% (19/229) | 4.06 (1.52–10.8) |

| III–IV (n= 164) | 8.5% (7/82) | 11.0% (9/82) | 1.29 (0.48–3.48) |

| Cardiothoracic ratio >55% | |||

| No (n=447) | 3.5% (8/230) | 8.8% (19/217) | 2.57 (1.13–5.88) |

| Yes (n=184) | 4.4% (4/90) | 9.6% (9/94) | 2.19 (0.68–7.13) |

| Overall | 3.8% (12/320) | 9.0% (28/311) | 2.46 (1.25–4.83) |

CI=confidence interval.

P values for the interaction of the variables shown are as follows: age, 0.830; sex, 0.019; race, 0.908; etiology of heart failure, 0.900; chronic kidney disease, 0.342; prior digoxin use, 0.957; ejection fraction, 0.381; New York Heart Association class, 0.527, and cardiothoracic ratio, 0.506.

HRs comparing patients in the digoxin group with those in the placebo group.

Digoxin and Other 30-Day Outcomes

There was only one death in the placebo group among patients aged ≥65 years. Consequently, the risk of the combined end point of 30-day all-cause hospitalization or all-cause mortality was also high in the digoxin group (HR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.17–4.38; Table 2). There were 6 hospitalizations due to worsening heart failure, 2 of which occurred in the digoxin group (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.09–2.79) and there were 7 hospitalizations due to unstable angina, all but one occurred in the digoxin group (HR, 6.21; 95% CI, 0.75–51.62; Table 2). Associations with other outcomes are displayed in Table 2.

Digoxin and 3- and 12- Month Outcomes

During the first 3 months after randomization, among patients aged ≥65 years, all-cause hospitalization occurred in 12.2% and 17.0% of those in the placebo and digoxin groups, respectively (HR for digoxin, 1.45; 95% CI, 0.96–2.20). There was no interaction between digoxin and sex (p=0.677) – with respective HRs of 1.57 (95% CI, 0.83–2.99) and 1.33 (95% CI, 0.77–2.27) for men and women. During this period, digoxin reduced the risk of heart failure hospitalization (4.7% vs. 1.6% for digoxin; HR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.12–0.93), but increased hospitalization due to unstable angina (0.9% vs. 4.2% for digoxin; HR, 4.53; 95% CI, 1.29–15.91). There were 5 and 6 deaths in the placebo and digoxin groups, respectively (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.38–4.05).

During the first 12 months after randomization, among patients aged ≥65 years, all-cause hospitalization occurred in 37.8% and 40.5% of those in the placebo and digoxin groups, respectively (HR for digoxin, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.90–1.46). There was no digoxin-sex interaction (p=0.705) at 12-months – HRs for men and women were 1.08 (95% CI, 0.76–1.53) and 1.19 (95% CI, 0.83–1.70), respectively. Digoxin decreased the risk of heart failure hospitalization (14.4% vs.8.4% for digoxin; HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.35–0.91), but increased the risk for hospitalization due to unstable angina (8.0% vs. 4.1% in the placebo group; HR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.06–4.03). There were 27 deaths in each treatment group (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.61–1.76).

Effect of Digoxin on 30-Day Outcomes in Patients <65 Years

Among the 357 patients <65 years, 30-day all-cause hospitalization occurred in 7.4% and 6.1% of patients in the placebo and digoxin groups, respectively, (HR for digoxin, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.36–1.79; Table 2 and Figure 1). Digoxin had no significant effect on any other outcomes (Table 2). There were only 4 hospitalizations due to worsening heart failure and 3 due to unstable angina, 1 of each occurring in the digoxin group, and the only death occurred in the placebo group (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Findings from the current analysis suggest that in the ancillary DIG trial digoxin increased the risk of 30-day all cause hospital admission in ambulatory older diastolic heart failure patients, but had no effect in younger diastolic heart failure patients. Although there were more events during 3 and 12 months of follow-up, the risks of all-cause hospital admission were not significantly different by treatment group during these longer follow-up durations that included the first month. These findings are in sharp contrast to the findings from the main DIG trial in which digoxin significantly reduced the risks of all-cause hospital admission in older systolic heart failure patients during the first 30 days after randomization, an effect that also lasted during longer follow-up. The current results based on a much smaller ancillary DIG trial may represent a chance effect and thus need to be interpreted with caution. The lack of an effect of digoxin in younger patients during the first 30 days and in older patients during longer follow-up suggest that unlike in systolic heart failure digoxin may have no beneficial effect on 30-day all-cause hospital admission in diastolic heart failure.

The increased risk of 30-day all-cause admission in the digoxin group was apparently driven by an increased risk of cardiovascular hospitalization, in particular that due to unstable angina. However, while the magnitude of the risk of 30-day unstable angina hospitalization in the digoxin group was strong, it was not statistically significant, likely due to small number of events (n=7). Importantly, even as the risk of unstable angina hospitalization became significant during longer follow-up, the risk of all-cause hospitalization became weaker and non-significant, likely due to a proportionate decreased risk of heart failure hospitalization. Therefore, unstable angina is unlikely to fully explain the increased risk of 30-day all-cause hospital admission among older diastolic heart failure patients in the ancillary DIG trial. A more plausible interpretation is that unlike in systolic heart failure, digoxin has no beneficial effect on 30-day all-cause hospitalization in diastolic heart failure. This is also consistent with findings form younger patients who had higher events for all-cause hospitalization in the placebo group but no increased risk in the digoxin group. Similarly, the sex difference in the effect of digoxin on 30-day all-cause admission needs to be interpreted with caution as this was also lost during both 3 and 12 months of follow-up.

Findings from the current study are consistent with a similar lack of a long-term effect of digoxin on all-cause hospitalization in diastolic heart failure in the ancillary DIG trial.7 In that trial, among patients in the placebo group, there were more hospitalizations due to heart failure (n=108; 22%) than due to unstable angina (n=62; 13%) during 37 months of mean follow-up.7 Although digoxin significantly decreased the risk of heart failure hospitalization by 4% (from 22% to 18%), it also increased the risk of unstable angina hospitalization by 4% (from 13% to 17%) – thus, there was no net difference in all-cause hospital admission between patients in the placebo (67%) and digoxin (68%) groups.7 In the main DIG trial, in contrast, in patients with systolic heart failure, digoxin reduced the risk of heart failure hospitalization by 8% (35% to 27%) during 37 months of mean follow-up, but had no effect on unstable angina hospitalizations (12% in both treatment groups) – thus, there was a net 3% significant reduction in all-cause hospital admission between patients in the placebo (67%) and digoxin (64%) groups.6 A post hoc analysis of DIG data suggested that the risk of unstable angina hospitalization was higher among those with higher ejection fraction, so that compared with ejection fraction <35%, those with 35–55% and >55% had 17% and 57% independent higher risk, respectively.8 It has been suggested that viable hypertrophied myocardium with abnormal coronary microcirculation may make patients with diastolic heart failure more prone to unstable angina.9–11 However, it is not clear why this risk might be higher among older patients receiving digoxin, and importantly, whether this risk would be attenuated in those receiving beta-blockers.

Findings from the current study are also consistent with findings from the Alabama Heart Failure Project in which among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure, a new discharge prescription of digoxin was associated with a significant lower risk of 30-day all-cause hospital readmission among those with ejection fraction <45%, but not among those with ≥45% (p-value for interaction, 0.145), a difference that became stronger and significant during first 12-month post-discharge (p for interaction, 0.019).12 Taken together, these findings suggest that digoxin may not reduce the risk of all-cause hospital readmission in patients with diastolic heart failure. Considering the small sample size of the current analysis based on the ancillary DIG trial (n=631) and the diastolic heart failure subset of the Alabama Heart Failure Project (n=457), these findings need to be replicated in future prospective studies of contemporary hospitalized older diastolic heart failure patients.

Findings from the current study are important as they suggest that digoxin should not be used for the sole purpose of readmission reduction in older patients with diastolic heart failure. Although digoxin is not recommended for use in these patients, it is often prescribed for indications such as atrial fibrillation, although digoxin does not appear to reduce mortality in these patients.13 Because of recent findings of beneficial effects of digoxin in reducing 30-day hospital admission and its clinical effectiveness in lowering 30-day hospital readmission in systolic heart failure,5,12 and its beneficial effect on heart failure hospitalization in diastolic heart failure,7 it is possible that these data may be extrapolated to those with diastolic heart failure, especially as clinicians and hospitals are under pressure to reduce 30-day all-cause readmission in heart failure, the leading cause for readmission.1

Our study has several limitations. Unlike the main DIG trial, the ancillary DIG trial was small and there were far fewer events during the first 30 days after randomization. Although the DIG trial was conducted on the pre-beta-blocker era of heart failure care, these drugs have not been shown to be effective in diastolic heart failure.14 The DIG trial was based on heart failure patients in normal sinus rhythm, thus limiting generalizability as atrial fibrillation is common in older diastolic heart failure patients. Data on serum digoxin concentration were collected one month after randomization,15 which precluded examination of prospective association with 30-day all-cause hospital admission.

CONCLUSIONS

Digoxin increased the risk of 30-day all-cause hospitalization in older chronic diastolic heart failure patients. Although a chance association cannot be ruled out as there were very few events during the first 30 days after randomization, no beneficial effect was observed during 3 and 12 months after randomization. Taken together with the findings from the main DIG trial and the Alabama Heart Failure Project,5,12 these data suggest that unlike in systolic heart failure, in which digoxin reduced the risk of 30-day all-cause hospital admission and was associated with lower 30-day all-cause hospital readmission, digoxin may have no such effect in diastolic heart failure.

Clinical Significance.

In a separate document, include a maximum of 3–4 bullet points that succinctly and specifically explain the clinical significance of your manuscript. Bullets should provide readers with your manuscript’s “take home” messages for practicing internists. Do not restate information that would be considered common knowledge. Do not call for additional research in this area.

Heart failure is the leading cause for hospital readmission and hospitals with above-average 30-day all-cause readmissions face financial penalties under the Affordable Care Act.

Prior studies suggest that digoxin may reduce the risk of 30-day all-cause hospital admission and readmission in systolic heart failure.

The new analysis of the ancillary DIG trial suggests that digoxin may increase the risk of 30-day all-cause hospital admission in diastolic heart failure.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) study was conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program, in collaboration with the DIG Investigators. This article was prepared using a limited access dataset obtained from the NHLBI and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the DIG Study or the NHLBI. Dr Ahmed was in part supported by the National Institutes of Health through grants (R01-HL085561, R01-HL085561-S and R01-HL097047) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have any conflict of interest related to this manuscript. Details of all financial disclosures of all authors have been submitted to the journal.

Authorship: Dr. Ahmed conceived the study hypothesis and developed the analysis plan in consultation with coauthors. Drs. Ahmed, Elbaz and Hashim wrote the first draft. Drs. Ahmed, Elbaz, Hashim and Patel conducted statistical analyses in collaboration with Drs. Morgan, McGwin, and Cutter. All authors interpreted the data, participated in critical revision of the paper for important intellectual content, and approved the final version. Drs. Ahmed, Elbaz, Hashim, Morgan and Patel had full access to the data.

Embargoed materials: To be presented at a Late-Breaking Clinical Trials Poster Session and the Rapid Fire Oral Presentation Session at the 2013 Heart Failure Society of America 17th Annual Scientific Meeting on September 23, 2013 at Orlando, Florida.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler J, Kalogeropoulos A. Hospital strategies to reduce heart failure readmissions: where is the evidence? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:615–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konstam MA. Heart failure in the lifetime of Musca Domestica (the common housefly) JACC: Heart Failure. 2013;1:178–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rau J. The New York Times. New York: 2012. [Access date: December 2, 2012]. Hospitals Face Pressure to Avert Readmissions. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/27/health/hospitals-face-pressure-from-medicare-to-avert-readmissions.html?_r=0. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourge RC, Fleg JL, Fonarow GC, Cleland JG, McMurray JJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Digoxin reduces 30-day all-cause hospital admission in older patients with chronic systolic heart failure. Am J Med. 2013;126:701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Digitalis Investigation Group Investigators. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:525–533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702203360801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Fleg JL, Zile MR, Young JB, Kitzman DW, et al. Effects of digoxin on morbidity and mortality in diastolic heart failure: the ancillary digitalis investigation group trial. Circulation. 2006;114:397–403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed A, Zile MR, Rich MW, Fleg JL, Adams KF, Jr, Love TE, et al. Hospitalizations due to unstable angina pectoris in diastolic and systolic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:460–464. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.08.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iriarte M, Caso R, Murga N, Faus JM, Sagastagoitia D, Molinero E, et al. Microvascular angina pectoris in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy and diagnostic value of exercise thallium-201 scintigraphy. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:335–339. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80549-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcus ML, Koyanagi S, Harrison DG, Doty DB, Hiratzka LF, Eastham CL. Abnormalities in the coronary circulation that occur as a consequence of cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Med. 1983;75:62–66. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nijland F, Kamp O, Verhorst PM, de Voogt WG, Visser CA. In-hospital and long-term prognostic value of viable myocardium detected by dobutamine echocardiography early after acute myocardial infarction and its relation to indicators of left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:949–955. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed A, Bourge RC, Fonarow GC, Patel K, Morgran CJ, Fleg JL, et al. Digoxin use and lower 30-day all-cause readmission for Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. Am J Med. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.08.027. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gheorghiade M, Fonarow GC, van Veldhuisen DJ, Cleland JG, Butler J, Epstein AE, et al. Lack of evidence of increased mortality among patients with atrial fibrillation taking digoxin: findings from post hoc propensity-matched analysis of the AFFIRM trial. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1489–1497. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez AF, Hammill BG, O’Connor CM, Schulman KA, Curtis LH, Fonarow GC. Clinical effectiveness of beta-blockers in heart failure: findings from the OPTIMIZE-HF (Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure) Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Love TE, Lloyd-Jones DM, Aban IB, Colucci WS, et al. Digoxin and reduction in mortality and hospitalization in heart failure: a comprehensive post hoc analysis of the DIG trial. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:178–186. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]