Abstract

RING finger protein 2 (RNF2) contains a conserved N-terminal RING finger domain and functions as an E3 ligase. As a member of the Polycomb group family of proteins, RNF2 also represses a number of genes involved in development, differentiation, malignant transformation and cell cycle. Herein, using chromatin immunoprecipitation cloning, 33 RNF2-responding loci were identified in the genome of HEK293 human kidney cells. Luciferase reporter assays showed that among them, 26 and 2 loci acted as a repressor and an activator, respectively. RNA interference revealed that the identified RNF2-responding sequences regulated the transcriptional activity of nearby promoters. This study may contribute to elucidating the mechanism underlying RNF2-mediated transcriptional regulation.

Keywords: PcG complex, RNF2, RNF2-responding loci

INTRODUCTION

RNF2, also known as dinG/RING1b, contains a conserved RING finger domain in its N-terminal region. The RING-HC type functions as an E3 ligase and interacts with Hip-2/hE2-25k and the S6’ protein (Lee et al., 2001; 2005). RNF2 protein is also a member of the Polycomb group (PcG) family of highly conserved transcriptional regulators, which repress a number of genes involved in development, differentiation, malignant transformation and the cell cycle (Choi et al., 2008; Sparmann and van Lohuizen, 2006; Vidal, 2009). PcG proteins are generally classified into two groups: Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1) and PRC2 on the basis of their association with distinct classes of complexes. RNF2 is a core component of PRC1.

In Drosophila, PcG complexes are recruited into Polycomb response elements (PREs), which are chromosomal specific regulatory elements several hundred base pairs in length. PREs contain the binding sites for several DNA-binding pro-teins, which interact with PcG proteins including Pleiohomeotic (PHO), Pleiohomeotic-like (PHOL), GAGA factor (GAF)/Pips-queak (PSQ), Zeste and DSP1. Binding sites for the Grainyhead (GRH) and members of the Sp1/KLF family are included in PREs (Bantignies and Cavalli, 2006; Ringrose and Paro, 2004). Each PRE consists of various binding sites for these DNA binding factors, possibly providing the PcG complexes with specificity for the transcriptional regulation of a number of genes (Bantignies and Cavalli, 2006; Ringrose and Paro, 2004). In contrast, in Drosophila, a few DNA-binding factor mammalian homologs have been identified genetically and functionally, such as the YY1 transcription factor and High-mobility group box2 (HMGB2), which are functional homologues of PHO and DSP1 (Brown et al., 1998; Janke et al., 2003; Schwartz and Pirrotta, 2008). Amammalian PRE, PRE-kr, regulates expression of MafB/Kreisler gene in mice (Sing et al., 2009).

Searching for RNF2-interacting loci within the entire genome in human cells is helpful in identifying mammalian PREs. Herein, we report the identification of RNF2-responding sequences in HEK 293 human kidney cells using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) cloning. The finding that the identified RNF2-responding sequences mostly repressed transcriptional activity of a nearby promoter adds to the known mammalian cell PREs and may help in elucidating the mechanism underlying PRC1-mediated transcriptional repression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, cell culture and transcfection

The pREP4-HS-Luc vector used to test transcriptional activity of the RNF2-responding sequences (Roh et al., 2007) was a kind gift from Dr. Keji Zhao, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (USA). For the luciferase reporter assays, the RNF2-responding sequences were cloned into the pREP4-HS-Luc vector by digestion with NotI and XhoI (Enzynomics). HEK 293 cells and HEK 293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 8% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco), streptomycin (50 ug/ml) and penicillin (50 U/ml). MKN 28 cells were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco), streptomycin (50 ug/ml) and penicillin (50 U/ml). The cells were incubated at 37℃ in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator and were transfected with short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression vectors or luciferase reporter vectors using poly-ethyleneimine (Sigma-Aldrich) as previously described (Lee et al., 2005).

RNF2 RNA interference (RNAi)

The shRNA expression vectors targeting RNF2 mRNA were described previously (Choi et al., 2008). Briefly, the following sequences were inserted into pSilencer 1.0-U6 shRNA expression vector (Ambion): shRNF2-4, 5′-TGG CAA TTG ATC CAG TAA TTT CAA GAG AAT TAC TGG ATC AAT TGC CAT TTT TT-3′; shRNF2-7, 5′-AGA ACA CCA TGA CTA CAA ATT CAA GAG ATT TGT AGT CAT GGT GTT CTT TTT TT-3′; shRNF2-8, 5′-GGC TAG AGC TTG ATA ATA ATT CAA GAG ATT ATT ATC AAG CTC TAG CCT TTT TT-3′; shGFP, 5′-GCT GAC CCT GAA GTT CAT CTT CAA GAG AGA TGA ACT TCA GGG TCA GCT TTT TT-3′; control shRNA, 5′-GAT CAG TGG CTT TCC TAA ATT CAA GAG ATT TAG GAA AGC CAC TGA TCT TTT TT-3′ (Choi et al., 2008). To select cells maintaining expression of the inserted shRNA, the shRNF2-4 sequence was inserted into the pSNU6-1.2 vector (Choi et al., 2005), which was designed to express shRNA under control of the U6 RNA promoter in mammalian cells and to carry the hygromycin B resistance gene. At a day after transfection, hygromycin B (Invitrogen) was added to the medium at a concentration of 0.2 mg/ml and maintained for 8 days.

Luciferase reporter assays

The luciferase reporter assays were described previously (Choi et al., 2008). Briefly, the luciferase reporter vectors containing the RNF2-responding sequences were constructed by subcloning the RNF2-responding DNA fragments into the pREP4-HS-Luc vector. HEK 293T or HEK 293 cells were cultured in wells of six-well plates and transfected with an appropriate combination of DNA. After 48 h, cell extracts were prepared and luciferase activities were measured using a luciferase assay system (Promega). To calculate the transfection efficiency, cell extracts were mixed with 2× β-galactosidase (β-gal) assay buffer containing 200 mM NaH3PO4, 2 mM MgCl2, 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1.33 mg/ml O-nitrophenyl-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG), and then incubated at 37℃ for 30 min. The mixtures were then measured using a microplate reader (BioRad) at a wavelength of 420 nm. Luciferase activity was normalized with reference to β-gal activity in the same cells. The extracts were then analyzed by Western blotting to evaluate the level of the protein expression.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and was used to synthesize cDNA with Superscript III (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. For PCR, 200 ng of the cDNA was used, and the amplifications were performed by incubation for 3 min at 95℃, followed by 25 cycles of 30 s at 95℃, 40 s at 55℃ and 30 s at 72℃. For real-time PCR, cDNA was added to a real-time PCR mixture that contained 2x SYBR Green PCR master mix (Takara) and gene-specific primers. The PCR mixture was incubated for 10 min at 95℃ followed by 45 cycles, each consisting of 10 s at 95℃, 20 s at 55℃ and 10 s at 72℃ using a LightCycler real-time PCR system (Roche). Assays were performed in triplicate, and were normalized with β-actin. The specific PCR primer pairs were as follows: RNF2, 5′-TGC AGC GAG GCA AG-3′ and 5′-AAA GGC TCA TTT GTG CTC-3′; NF2, 5′-ACC GTT GCC TCC TGA CAT AC-3′ and 5′-TCG GAG TTC TCA TTG TGC AG-5′; JARID1A, 5′-TCA GAG TGG CAG CAA TTA CG-3′ and 5′-CCA ATC CTT CCT CCA GAT CA-3′; HDAC9, 5′-CAG GCT GCT TTT ATG CAA CA-3′ and 5′-TTT CTT GCA GTC GTG ACC AG-3′; SLC29A2, 5′-GCA CCT GAG AGG AGG AAC AG-3′ and 5′-ACC ACG GAC CAG TCA CTT TC-3′; ODZ1, 5′-TGC TTT GCG ATG ACA GTT TC-3′ and 5′-TCA AGC TGG TGT GTT TCC AG-3′; β-actin 5′-CCA ACT GGG ACG ACA TGG AG-3′ and 5′-GCA CAG CTT CTC CTT AAT GTC-3′

ChIP and ChIP cloning

ChIP and ChIP cloning were performed as previously described (Choi et al., 2008; Pan et al., 2005; Shunmei et al., 2010; Wein-mann et al., 2001). Briefly, transiently transfected HEK 293 cells or native cells were cultured on 150 mm-diameter dishes and were cross-linked by the addition of formaldehyde (1% final concentration). Cross-linking was terminated by addition of glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM. The cross-linked cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), harvested and incubated in ice-cold cell lysis buffer (5 mM pH 8.0 pipes, 85 mM KCl, 0.5% NP-40 and protease inhibitors) for 10 min. The nuclei pelleted by centrifugation were resuspended in nuclei lysis buffer (50 mM, pH 8.1 Tris-HCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1% sodium do-decyl sulfate (SDS) and protease inhibitors) and incubated on ice for 10 min followed by sonication. The collected supernatants were diluted with ChIP dilution buffer (16.7 mM, pH 8.1 Tris-HCl, 0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton X-100, 1.2 mM EDTA, 167 mM NaCl and protease inhibitors) and then 45 ul of a 50% slurry protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin and 0.1 mg/ml herring sperm DNA at 4℃ for 30 min. The supernatants were incubated with specific RNF2 antibody or non-specific IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4℃ overnight. RNF2 antibodies were generated with the His-tagged RNF2158-214, similar to previous studies (Choi et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2008). Forty-five microliters of 50% slurry protein A-Sepharose were then added as in the pre-clearing step and incubated for 1 h at 4℃. The beads were washed sequentially with rotation for 5 min each in low salt wash buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM pH 8.1 Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl), high salt wash buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM, pH 8.1 Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl), LiCl wash buffer (0.25 M LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% deoxychloate, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM, pH 8.0 Tris-HCl) and twice with TE (10 mM, pH 8.0 Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA). Bound proteins were eluted twice from the beads with 250 ul of elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3) for 20 min with rotation. The eluants were incubated with 1 ug RNase A and 0.3 M NaCl for 6 h at 65℃ to rescue the cross-link and then pelleted following the addition of ethanol. The pellets were resuspended in a buffer containing 10 mM EDTA, 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.5) and 0.2 mg/ml proteinase K, incubated at 45℃ for 2 h and then purified using the PCRquick-spin kit (Intron). To detect specific DNA sequences from the immunoprecipitated DNA fragments, PCR amplification was performed using the T7 and T3 primers flanked at the multiple cloning sites (MCS) of pBluescript II vector. The PCR protocol consisted of incubation for 3 min at 95℃, followed by 30 cycles each consisting of 30 s at 95℃, 30 s at 55℃ and 30 s at 72℃. The sequences of the PCR primer pairs were: T7, 5′-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GG-3′ and T3, 5′-ATT AAC CCT CAC TAA AGG GA-3′. To detect the site occupied by the RNF2 protein on the human chromatin, the immunoprecipitated DNA fragments were amplified using following primer pairs: F21-17, 5′-ACA CAG TGA GAC TCT GTC TC-3’ and 5′-CGT GTT ACC ATG TCT GTC TAA A-3′; G16-18, 5′-AAG AGG TGC AAC CCA AC-3′ and 5′-GGC AAA ACC CTG TCT CTA CT-3′; F2-23, 5′-TTC TTT CAC TTA AAA GAA AGA CAC-3′ and 5’-TCT AAT ATT AGG GGT GGG AAA-3′; G11-18, 5′-TGG GCC AAG TCC AC-3′ and 5′-TCT CAT CCA AGT CAG GAC A-3′; β-actin, 5′-GCA GGC CTG GCC ATG CG-3′ and 5′-AGT TTT GGC GTT GGC CGC CTT-3′. The PCR protocol comprised incubation for 5 min at 95℃, followed by 27 cycles each consisting of 30 s at 95℃, 30 s at 60℃ or 65℃ and 10 s at 72℃.

For ChIP cloning, the immunoprecipitated DNA was eluted with elution buffer and diluted with the ChIP dilution buffer. Once again, the same antibodies as were used in the first immunoprecipitation were added into the diluted eluants and incubation, bead binding, washing and elution steps were sequentially repeated. The cross-links were reversed, and the samples were sequentially treated with RNase A and proteinase K, and then isolated as performed in the ChIP assay. The isolated DNA fragments were blunted with T4 DNA polymerase (NEB), and cloned into the HindV site of the pBluescript II vector.

Sequence analysis

To determine the location and flanking genes on the RNF2-responding loci on the chromosomes, a Human BLAST Search of UCSC Genome Bioinformatics (http://genome.ucsc.edu) and the BLAST of NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) was used.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of RNF2-responding loci in the genome of HEK 293 cells

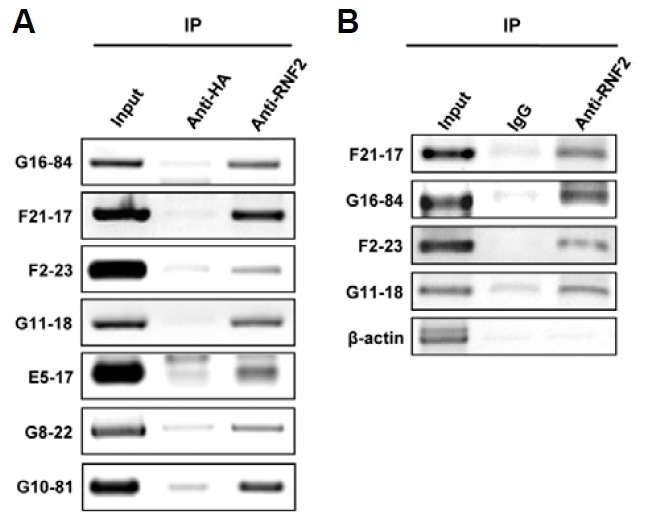

RNF2 protein is a core component of PRC1 that binds to various regions of the chromatin. To identify the RNF2 complex-responding sites on the human genome, ChIP experiments were carried out using an antibody specific to RNF2 and the precipitated RNF2-responding DNA fragments were cloned into a pBluescript II vector. We obtained more than 300 clones. To confirm whether the cloned DNA sequences could interact with endogenous RNF2 proteins, we transfected HEK293 cells with empty plasmid or each of the 41 plasmids containing RNF2-responding DNA fragments randomly selected from the 300 clones. ChIP experiments were done using anti-RNF2 antibody. If the cloned DNA fragments interacted with the RNF2, they would be precipitated and amplified by PCR using the primer pair targeting the T7 and T3 promoters located in the vector. As shown in Fig. 1A, precipitants were detected by PCR amplification using this primer pair.

Fig. 1. ChIP cloning identification of RNF2-responding sequences. (A) HEK 293 cells were transfected with the cloned RNF2-responding sequence into a vector, and a ChIP assay was performed with RNF2 antibodies or non-specific IgG. The immunoprecipitated DNA fragments were analyzed by PCR amplification using the T7 primer and T3 primer pair. (B) RNF2-responding DNA fragments in the human chromatin were immunoprecipitated with RNF2 antibodies or non-specific IgG, and amplified with specific primer pairs corresponding to the RNF2-responding sequences.

To test whether endogenous RNF2 could bind to the RNF2-responding loci on the genome of human cells as well as on the cloned plasmids, ChIP experiments using antibodies against RNF2 were carried out in HEK293 cells that did not contain the plasmids. The precipitated DNA fragments were then PCR-amplified with specific primers for the RNF2-responding sequences. Endogenous cellular RNF2 interacted with the RNF2-responding loci in the human genome (Fig. 1B). Table 1 shows 33 RNF2-responding loci that were confirmed by ChIP experiments using antibodies against the RNF2, as shown in Fig. 1A. RNF2-responding loci were dispersedly located in the whole human genome. The lengths of the cloned RNF2-responding DNA fragments varied from 100-3000 bp and most of the fragments were approximately 400 bp in size.

Table 1.

The chromosomal location and characterization of the individual RNF2-responding loci.

| Clone | Chromosome: position | Relative reporter gene activity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repression | F13-48 | chr1: 38983618-38984571 | 66.9 ± 4.7 |

| G10-81 | chr2: 111180744-111180967 | 31.2 ± 0.1 | |

| G6-12 | chr2: 158018504-158019459 | 36.7 ± 1.0 | |

| G11-11 | chr2: 173690246-173690484 | 58.4 ± 0.4 | |

| A6-13 | chr2: 213056901-213057167 | 55.9 ± 2.4 | |

| D26-16 | chr5: 35475709-35476246 | 63.7 ± 3.9 | |

| G13-91 | chr6: 42065672-42065899 | 52.9 ± 8.1 | |

| G10-94 | chr6: 47303126-47303282 | 34.1 ± 1.4 | |

| G8-22 | chr7: 18785005-18785954 | 20.6 ± 2.3 | |

| A1-21 | chr8: 35815728-35816052 | 45.1 ± 3.9 | |

| G13-9 | chr8: 59253395-59253683 | 41.1 ± 3.5 | |

| G13-54 | chr9: 5245917-5246193 | 54.1 ± 2.8 | |

| F1-4 | chr9: 109777398-109777922 | 68.5 ± 3.6 | |

| G7-64 | chr9: 110302743-110303030 | 36.0 ± 0.6 | |

| G11-18 | chr11: 65889385-65889595 | 48.1 ± 2.6 | |

| F16-6 | chr11: 69084416-69084891 | 60.6 ± 3.3 | |

| G2-31 | chr11: 124922953-124923108 | 63.5 ± 3.5 | |

| F21-17 | chr12: 306959-307376 | 36.6 ± 2.0 | |

| D21-19 | chr12: 16914512-16915223 | 26.4 ± 1.1 | |

| F2-49 | chr17: 42576326-42587076 | 56.1 ± 3.1 | |

| G16-84 | chr20: 31530709-31531293 | 53.7 ± 3.2 | |

| E20-19 | chr20: 35797629-35798138 | 49.4 ± 7.9 | |

| D25-56 | chr22: 23185152-23185347 | 44.8 ± 5.0 | |

| E5-17 | chr22: 28369137-28369399 | 21.3 ± 0.7 | |

| F2-23 | chrx: 123583809-123583991 | 51.4 ± 2.9 | |

| G22-7 | chrx: 132461988-132462261 | 50.7 ± 7.0 | |

| Non-Effect | A7-16 | Chr1: 237496939-237497468 | 81.1 ± 0.6 |

| G12-80 | Chr5: 138037756-138037936 | 107 ± 11.2 | |

| D21-12 | Chr6: 43901193-43901464 | 89.5 ± 9.1 | |

| D24-24 | Chr8: 21155830-21156120 | 110.6 ± 9.4 | |

| G16-77 | Chr13: 107691302-107691600 | 92.2 ± 8.2 | |

| Activation | F22-12 | Chr8: 27167766 27168040 | 200.4 ± 25.5 |

| G21-39 | Chr10: 121325085 121325271 | 183.2 ± 25.2 | |

Thirty-three RNF2-responding sequences identified by the ChiP cloning method and confirmed by ChiP assay were inserted into the pREP4-Hs luciferase reporter vector. HEK 293t cells were transfected with the constructs containing the RNF2-responding sequences and then reporter gene activities of each construct were analyzed by luciferase re-porter assays. The reporter gene activities were compared with lucife-rase assay data for empty vector. The results were presented as the mean of three independent experiments. The numbers of reporter gene activity were significant at P ˂ 0.05 versus the control (Student’s t-test).

RNF2-responding sequences are mostly involved in the regulation of transcriptional activity

We used a luciferase reporter assay to evaluate whether the RNF2-responding sequences regulated the transcriptional activity of nearby promoters. For this assay, we constructed plasmids containing RNF2-responding sequences in the upstream region of the heat-shock promoter, which regulates the transcription of the luciferase reporter gene. These constructs were transiently transfected into HEK 293T cells and then the reporter activity of each construct was compared with that of the same luciferase reporter vector without an insert. Among the 33 RNF2-responding sequences confirmed by the ChIP assay, 26 sequences repressed transcription of the luciferase reporter gene (Table 1). However, two RNF2-responding sequences activated transcription of the luciferase reporter gene and five loci did not show a meaningful effect.

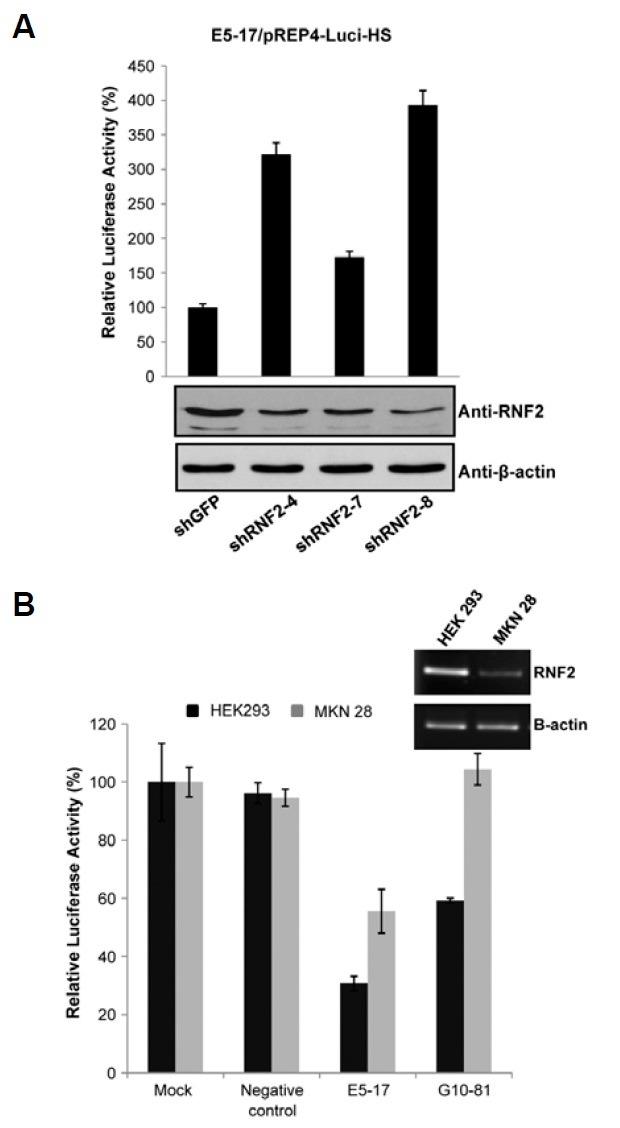

RNAi experiments were next undertaken to investigate whether the repressor activity of RNF2-responding sequences could be directly regulated by the presence of the RNF2 protein. After three shRNA expression vectors targeting RNF2 mRNA were constructed, each shRNA vector and reporter vector with or without the E5-17 RNF2-responding sequence were transiently co-transfected into HEK 293 cells. The E5-17 sequence was chosen for the RNAi experiments, since the repression activity of the sequence was very strong. As expected, reduction of RNF2 protein by shRNF2 expression increased luciferase activity in the transfected HEK293 cells with reporter vector containing the E5-17 RNF2-responding sequence, but not in the transfected HEK 293 cells with empty reporter vector, consistent with the notion that the transcriptional repression activity of the E5-17 sequence is dependent on the presence of the RNF2 protein (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 2. RNF2 protein regulates the silencer activity of the RNF2-responding sequences. (A) HEK 293 cells were co-transfected with RNF2 shRNA expression vectors and the pREP4-Hs-Luc luciferase reporter vector containing the E5-17 RNF2-responding sequence. Repression activity of the RNF2-responding sequence was reduced in the RNF2 knock-down cells. (B) Comparison of repression activity of the E5-17 sequence in MKN 28 cells and HEK 293 cells. RNF2 expression levels were analyzed by RT-PCR. RNF2 expression was greater in HEK 293 cells than in MKN 28 cells. Both cell types were transfected with the pREP4-Hs luciferase reporter vector containing the E5-17 and G10-81 RNF2-responding sequences. Repression activities of the E5-17 and G10-81 RNF2-responding sequences were more reduced in HEK 293 cells than in MKN 28 cells, but a negative control that had no effect on the reporter activity in HEK 293 cells displayed the same effect in both HEK 293 and MKN 28 cells. The black and gray bars indicate luciferase activity in HEK 293 cells and MEK 28 cells, respectively. The results are presented as the means of three independent experiments.

The level of RNF2 expression differs between various tissues (Sanchez-Beato et al., 2006). The repression activity of the E5-17 and G10-81 sequences in MKN28 cells, which were originated from stomach adenocarcinoma cells, was compared with that in HEK293 cells, since the expression level of RNF2 is lower in MKN 28 cells than in HEK 293 cells (Fig. 2B). The E5-17 and G10-81 sequences were chosen for this experiment, since the repression activity of the sequences was very strong. As expected, the transcriptional activities of constructs containing the RNF2-responding sequences were higher in MKN 28 cells than in HEK293 cells (Fig. 2B), confirming that the transcriptional regulation activity of RNF2-responding sequence depended on the presence of RNF2.

RNF2-responding sequences regulated expression of adjacent genes in the chromatin

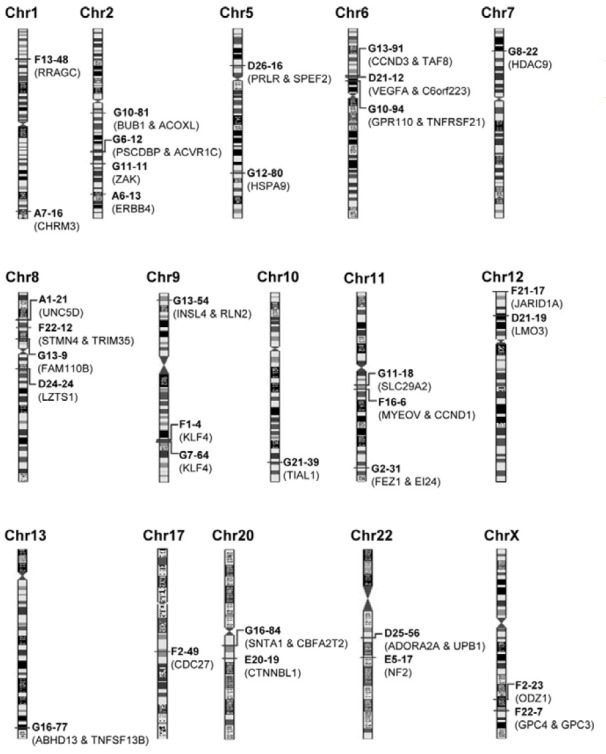

We attempted to identify genes that are regulated by RNF2-responding loci. Previous studies of the Drosophila PcG complexes demonstrated that PREs are cis-acting sequences and PcG complexes mostly regulate the transcription of flanking genes on the PRE (Bloyer et al., 2003). We identified all of the genes flanking 33 RNF2-responding loci using the BLAST program from NCBI (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Genes adjacent to RNF2-responding sequences. Thirty-three RNF2-responding sequences and adjacent genes were indicated in the entire human genome. The lengths between chromosomes were not considered to clarify the loci on each chromosome.

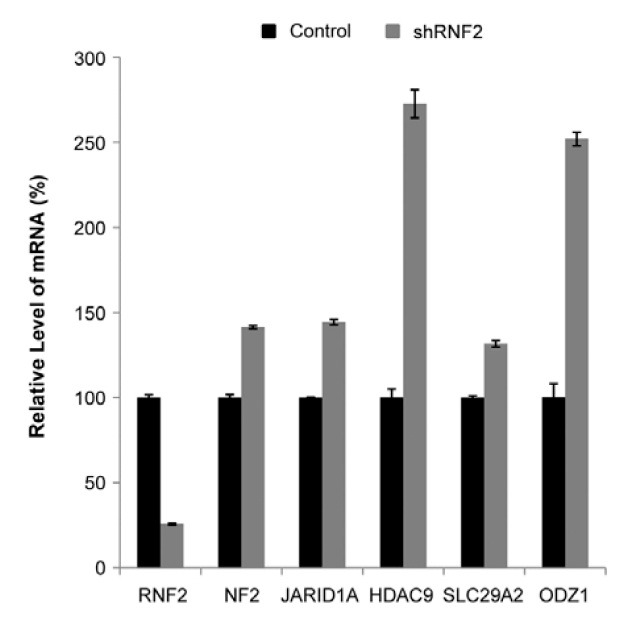

To confirm whether RNF2 was involved in the transcriptional regulation of the genes adjacent to the RNF2-responding loci, we analyzed the mRNA expression level of several flanked genes after knock-down of RNF2 expression. Firstly, we ran-domly chose five RNF2-responding loci as follows: NF2 (neurofibromin 2) adjacent to the E5-17 sequence, JARID1A (jumonji, AT rich interactive domain 1A) adjacent to the F21-17 sequence, HDAC9 (histone deacetylase 9) adjacent to the G8-22 sequence, SLC29A2 [solute carrier family 29 (nucleoside transporters), member 2] adjacent to the G11-18 sequence and ODZ1 (odz, odd Oz/ten-m homolog 1) adjacent to the F2-23 sequence. HEK 293 cells were transfected with the co-expressed vector with the shRNF2 and hygromycin resistance gene, and then incubated with hygromycin B to select the cells maintaining the knock-down status of RNF2. Next, total RNA was prepared and the relative mRNA level of each gene was analyzed using real-time PCR with specific primers of each gene. As expected, the transcription level of all genes was increased in the cells with reduced RNF2 by shRNF2 expression (Fig. 4), demonstrating that RNF2 is involved in the transcriptional regulation of the genes adjacent to the RNF2-responding loci. We only used the RNF2-responding sequences in the luciferase reporter assays, although PREs contain binding sites for several DNA-binding proteins. However, the in vivo transcription of the adjacent genes of the identified RNF2-responding loci might be regulated not only by the RNF2-responding loci with RNF2 protein, but also by other elements and transcription factors. This may cause the discrepancy between mRNA level of adjacent genes and luciferase reporter activity of some RNF2-responding loci such as the E5-17 loci.

Fig. 4. Transcription levels of genes adjacent to RNF2-responding sequences. HEK 293 cells transfected with a shRNF2 expression vector were incubated with hygromycin B for 8 days and total RNAs were obtained. The relative mRNA level of each gene was analyzed by real-time PCR using the specific primers of each gene. The black bar indicates the relative mRNA level in the cells transfected with control shRNA expression vector. The gray bar indicates the relative mRNA level in the cells transfected with a shRNF2 expression vector. The results are presented as the mean of three independent experiments. P < 0.002 versus the control shRNA (Student’s t-test).

The RNF2 protein functions as an ubiquitin E3 ligase or/and transcriptional repressor (Choi et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2001; 2005). RNF2 is one of core components of PRC1 and plays a role as a main E3 ligase that ubiquitylates lysine 119 of histone H2A (de Napoles et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2004). PcG complexes including RNF2 physically interact with a number of regions on chromatin to repress the transcription of nearby genes. Herein, we identified and characterized 33 loci in the whole genome of human kidney cells. We used cells from the HEK 293 cell line in this study. Our results of RNF2-responding sequences differ from those in murine embryonic stem cells. The differences between the cell types could be due to the differences in the role of RNF2 in the regulation of gene expression between the cell lineages, and suggests that RNF2 could change after the differentiation process (Boyer et al., 2006; Squazzo et al., 2006).

ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq are usually used for genome-wide mapping of protein-DNA interaction and epigenetic makers, respectively, whereas the out-of-date ChIP-cloning method is rarely used. Presently, we introduced the ChIP-cloning method since, to identify overrepresented motifs and RNF2-responding sequences with high similarity on the whole human genome, longer sequences should be cloned. Using the ChIP-cloning method, various lengths of fragments ranging from 100-3000 bp were cloned (most of the fragments were approximately 400 bp). This approach proved advantageous in cloning the RNF2-responding sequences.

After cloning, we investigated the repression activity of the RNF2-responding loci. More than 78% of the RNF2-responding sequences displayed repressor activity, which is consistent with previous studies about the function of RNF2 and the PcG pro-tein (Lee et al., 2008; Schwartz and Pirrotta, 2008; van der Stoop et al., 2008). Using the ChIP-cloning approach, we found RNF2-responding loci that were dispersedly located in the whole human genome. However, there were a number of RNF-2 responding loci that could not be confirmed or detected.

Our previous experiments (data not shown) revealed that the expression of luciferase reporter gene is much stronger at the upstream region of cytomegalovirus promoter than at the upstream region of heat-shock promoter in the luciferase reporter vector. For this study, however, we used the heat-shock promoter because the weak promoter was more effectively regulated by RNF2-responding sequences. As shown in Table 1, 21% of the RNF2-responding sequences did not repress the activity of heat-shock promoter in the luciferase reporter vector. We think that some of the RNF2-responding sequences might not be effective to the heat-shock promoter, while being effective to other promoters.

Although PREs of Drosophila have been ascertained, mammalian PREs have been poorly studied. In this study, we identified RNF2-responding loci in the whole genome of human cells using ChIP. We think that most of the RNF2-responding sequences are PREs. This information adds to the known mammalian cell PREs and may help in elucidating the mechanism underlying the transcriptional repression by PRC1.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Molecules and Cells website (www.molcells.org).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea [C00216]; the Korea Research Foundation [2009-0074201].

References

- 1.Bantignies F., Cavalli G. Cellular memory and dynamic regulation of polycomb group proteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. (2006);18:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloyer S., Cavalli G., Brock H.W., Dura J.M. Identification and characterization of polyhomeotic PREs and TREs. Dev. Biol. (2003);261:426–442. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00314-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyer L.A., Plath K., Zeitlinger J., Brambrink T., Medeiros L.A., Lee T.I., Levine S.S., Wernig M., Tajonar A., Ray M.K., et al. Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature. (2006);441:349–353. doi: 10.1038/nature04733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown J.L., Mucci D., Whiteley M., Dirksen M.L., Kassis J.A. The Drosophila Polycomb group gene pleiohomeotic encodes a DNA binding protein with homology to the transcription factor YY1. Mol. Cell. (1998);1:1057–1064. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi I., Cho B.R., Kim D., Miyagawa S., Kubo T., Kim J.Y., Park C.G., Hwang W.S., Lee J.S., Ahn C. Choice of the adequate detection time for the accurate evaluation of the efficiency of siRNA-induced gene silencing. J. Biotechnol. (2005);120:251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi D., Lee S.J., Hong S., Kim I.H., Kang S. Prohibitin interacts with RNF2 and regulates E2F1 function via dual pathways. Oncogene. (2008);27:1716–1725. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Napoles M., Mermoud J.E., Wakao R., Tang Y.A., Endoh M., Appanah R., Nesterova T.B., Silva J., Otte A.P., Vidal M., et al. Polycomb group proteins Ring1A/B link ubiquitylation of histone H2A to heritable gene silencing and X inactivation. Dev. Cell. (2004);7:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janke C., Martin D., Giraud-Panis M.J., Decoville M., Locker D. Drosophila DSP1 and rat HMGB1 have equivalent DNA binding properties and share a similar secondary fold. J. Biochem. (2003);133:533–539. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee S.J., Choi J.Y., Sung Y.M., Park H., Rhim H., Kang S. E3 ligase activity of RING finger proteins that interact with Hip-2, a human ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. FEBS Lett. (2001);503:61–64. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02689-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S.J., Choi D., Rhim H., Kang S. E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF2 interacts with the S6′ proteasomal ATPase subunit and increases the ATP hydrolysis activity of S6′. Biochem. J. (2005);389:457–463. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S.J., Choi D., Rhim H., Choo H.J., Ko Y.G., Kim C.G., Kang S. PHB2 interacts with RNF2 and represses CP2c-stimulated transcription. Mol. Cell. Biochem. (2008);319:69–77. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9878-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan X., Song Z., Zhai L., Li X., Zeng X. Chromatin-remodeling factor INI1/hSNF5/BAF47 is involved in activation of the colony stimulating factor 1 promoter. Mol. Cells. (2005);20:183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ringrose L., Paro R. Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. (2004);38:413–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roh T.Y., Wei G., Farrell C.M., Zhao K. Genome-wide prediction of conserved and nonconserved enhancers by histone acetylation patterns. Genome Res. (2007);17:74–81. doi: 10.1101/gr.5767907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez-Beato M., Sanchez E., Gonzalez-Carrero J., Morente M., Diez A., Sanchez-Verde L., Martin M.C., Cigudosa J.C., Vidal M., Piris M.A. Variability in the expression of polycomb proteins in different normal and tumoral tissues. A pilot study using tissue microarrays. Mod. Pathol. (2006);19:684–694. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz Y.B., Pirrotta V. Polycomb complexes and epigenetic states. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. (2008);20:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shunmei E., Zhao Y., Huang Y., Lai K., Chen C., Zeng J., Zou J. Heat shock factor 1 is a transcription factor of Fas gene. Mol. Cells. (2010);29:527–531. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sing A., Pannell D., Karaiskakis A., Sturgeon K., Djabali M., Ellis J., Lipshitz H.D., Cordes S.P. A vertebrate Polycomb response element governs segmentation of the posterior hindbrain. Cell. (2009);138:885–897. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sparmann A., van Lohuizen M. Polycomb silencers control cell fate, development and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. (2006);6:846–856. doi: 10.1038/nrc1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Squazzo S.L., O’Geen H., Komashko V.M., Krig S.R., Jin V.X., Jang S.W., Margueron R., Reinberg D., Green R., Farnham P.J. Suz12 binds to silenced regions of the genome in a cell-type-specific manner. Genome Res. (2006);16:890–900. doi: 10.1101/gr.5306606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Stoop P., Boutsma E.A., Hulsman D., Noback S., Hei-merikx M., Kerkhoven R.M., Voncken J.W., Wessels L.F., van Lohuizen M. Ubiquitin E3 ligase Ring1b/Rnf2 of polycomb repressive complex 1 contributes to stable maintenance of mouse embryonic stem cells. PLoS ONE. (2008);3:e2235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vidal M. Role of polycomb proteins Ring1A and Ring1B in the epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Int. J. Dev. Biol. (2009);53:355–370. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082690mv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H., Wang L., Erdjument-Bromage H., Vidal M., Tempst P., Jones R.S., Zhang Y. Role of histone H2A ubiquitination in Polycomb silencing. Nature. (2004);431:873–878. doi: 10.1038/nature02985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinmann A.S., Bartley S.M., Zhang T., Zhang M.Q., Farnham P.J. Use of chromatin immunoprecipitation to clone novel E2F target promoters. Mol. Cell. Biol. (2001);21:6820–6832. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.6820-6832.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]