Abstract

Stroke is the leading cause of adult disability in the United States. To date there is no satisfactory treatment for stroke once neuronal damage has occurred. Human adult bone marrow-derived somatic cells (hABM-SC) represent a homogenous population of CD49c/CD90 co-positive, non-hematopoietic cells that have been shown to secrete therapeutically relevant trophic factors and to support axonal growth in a rodent model of spinal cord injury. Here we demonstrate that treatment with hABM-SC after ischemic stroke in adult rats results in recovery of forelimb function on a skilled motor test, and that this recovery is positively correlated with increased axonal outgrowth of the intact, uninjured corticorubral tract. While the complete mechanism of repair is still unclear, we conclude that enhancement of structural neuroplasticity from uninjured brain areas is one mechanism by which hABM-SC treatment after stroke leads to functional recovery.

Introduction

Stroke is the most frequent cause of adult onset neurological disability in the United States (Thom, et al., 2006). Neuronal loss may lead to permanent deficits in sensory, language, visual and motor systems. The only current available treatment for stroke is during the first few hours after onset, and many patients are not able to receive this treatment in such a short time window (Maestre-Moreno, et al., 2005). Of the various therapeutic modalities currently under investigation for the treatment of stroke, non-hematopoietic adult bone marrow-derived cells, collectively referred to as bone marrow stromal cells (MSC), have shown great promise (Chen, et al., 2001, Liu, et al., 2007, Zhao, et al., 2002). While various MSC isolates have been characterized (Digirolamo, et al., 1999, Goshima, et al., 1991, Sensebe, et al., 1995), human adult bone marrow-derived somatic cells (hABM-SC) represent a substantially homogenous population of human MSC that co-express the cell surface markers CD90/CD49c but lack expression of the pan-hematopoietic marker CD45. hABM-SC maintain a stable phenotype over 40 population doublings and secrete various trophic factors known to augment tissue repair.

Our laboratory has shown that by promoting neuronal plasticity in the adult CNS, neuronal repair and functional recovery is possible after various types of injury, including ischemic stroke, (for recent reviews, see Cheatwood, et al., 2008, Gonzenbach and Schwab, 2007). Therefore, we hypothesized that the improved functional recovery, as observed in previous studies of stroke and treatment with hABM-SCs, is due to new axonal outgrowth from the uninjured, spared hemisphere to deafferented, subcortical structures. We found that animals treated with hABM-SCs one week after stroke had significant functional recovery on a skilled forelimb task, and that this recovery correlated with increased corticorubral sprouting from the uninjured, contralateral cortex.

Materials and Methods

The subjects, adult male Long Evans black-hooded rats (250-300g) (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN), were divided into two experimental groups, blinded to investigators: (1) Stroke plus hAB-MSC (n=12) or (2) Stroke plus vehicle control (n=10). Experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Hines Veterans Affairs Hospital. Animals were reduced to 90-95% of their total body weight and maintained on a restricted diet. All animals were trained on the skilled forelimb reaching task for up to 3 weeks to establish limb preference and baseline measurements (an average of the last three testing sessions of preoperative training), as described earlier (Tsai, et al., 2007). The success rate, i.e. the number of pellets grasped with the preferred limb (as determined during training) and placed into the mouth out of 20 attempts, was recorded (Fig 1A-D). Prior to MCAO, animals were required to reach a baseline value of 16 or greater pellets out of 20 attempts with the preferred limb in order to be included in the study. In the week following stroke, animals needed to show a deficit of less than 6 pellets out of 20 attempts with the preferred limb to remain in the study. Following MCAO, animals were tested five days a week for 10 weeks and then used for the anatomical tracing study.

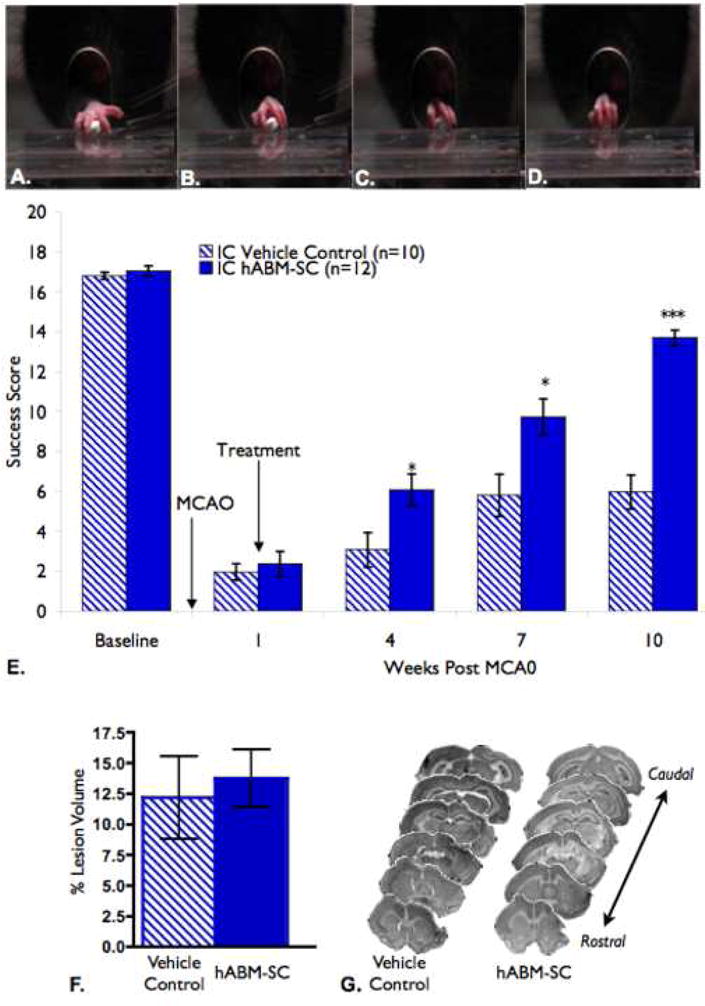

Fig. 1.

(A-D) The skilled forelimb reaching task is a test for skilled forelimb movement in which the animal is required to reach through an opening and grasp a small food pellet. (A-D) Digit movement during normal reach is shown; Limb Extension and Digit spread (A), Grasp (B), Retraction (C,D). Normal animals can grasp 20 pellets in less than a minute, with making only 1-3 errors. (E) hABM-SC therapy improves success on the forelimb reaching task. hABM-SC treatment one week after the stroke lesion improve success scores on the skilled forelimb reaching test, reaching significance at 4 weeks following stroke as compared to the control group (two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), p = .0.0003, with Bonferonni post-tests at each time point, *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001, error bars indicate standard error. Success scores for the hABM-SC group continued to improve, and at 10 weeks post stroke they reached a success score equivalent to 80% of their baseline score. The control group only recovered to 36% of their own baseline success score at the same time point. (F,G). hABM-SC therapy did not affect lesion size as compared to vehicle controls. The Percent Lesion Volume is presented as a percentage of he intact hemisphere. (F) The control group had a mean lesion size of 13.76 % +/- 3.252% and the hABM-SC group had a mean of 13.07% +/- 2.012% (p=0.4257, student's t-test, error bars represent standard error). (G) Representative sections to depict lesion sizes are shown for both groups. Notice that the MCAO resulted in a cortical lesion and did not greatly affect the subcortical structures

In preparation for the MCAO, animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg; i.p.) and a craniotomy was made to expose the middle cerebral artery corresponding to the preferred limb. Using a 10-0 suture, the MCA was permanently occluded and transected with micro-scissors. The common carotid artery (CCA) ipsilateral to the MCAO was permanently occluded, while the contralateral CCA was occluded for 60 minutes. Body temperature was maintained with a heating pad and monitored with a rectal probe. The wound was then closed and animals were warmed under a heating lamp until awake.

One week after MCAO, animals were re-anesthetized and and the hABM-SCs were injected ipsilateral to the stroke lesion using a hamilton syringe attached to a 27 gauge needle. Frozen lots of hABM-SC (Neuronyx, Inc., Malvern, PA), prepared from a single donor (as described by Himes, et al., 2006), were thawed and the concentration of viable cells was determined. The hABM-SCs were centrifuged, and the cell pellet was resuspended in injection vehicle to yield 5 × 104 cells per μl. A total of 1.5×106 cells were injected into three sites relative to bregma (5×105 cells per site): 2mm anterior, 1 mm lateral; 1 mm posterior, 1 mm lateral; 3 mm posterior, 2 mm lateral; all 3 sites, 1.5 mm ventral. All animals were immunosuppressed with cyclosporin-A (10 mg/kg, intraperitoneal (i.p.)) daily for 15 days, beginning the day prior to treatment. Biweekly cyclosporin injections were given for the remainder of the study.

After behavioral testing was completed (10 weeks post MCAO), the animals were anesthetized and 1 μl of a 10% biotinylated dextran amine (BDA) solution was injected into two areas of the contralesional sensorimotor cortex for anterograde tracing of the corticorubral tract (coordinates: 0.5 mm rostral, 2.5 mm lateral and 1.5 mm ventral to bregma; 1.0 mm anterior, 3.0 mm lateral and 1.5 mm ventral to bregma). Two weeks after BDA injection, animals were overdosed with sodium pentobarbital and perfused with 4% paraformaldeyhyde. Brains were cut into 50 μm coronal sections and reacted for BDA and counterstained for Nissl.

BDA-positive fibers at the level of the parvocellular red nucleus were analyzed by counting the number of BDA-labeled fibers crossing the midline of five consecutive sections per animal. To correct for the inter-animal tracing differences, the values were divided by the total number of labeled corticospinal tract fibers in the cerebral peduncle and expressed as fibers crossing the midline per ten thousand labeled CST axons as previously described (Papadopoulos, et al., 2002).

The stroke volume of each animal was quantitatively analyzed from Nissl stained sections and was expressed as a percentage of the intact contralateral hemispheric volume as described previously (Papadopoulos, et al., 2002).

Statistical analysis of data was performed using Prism 4 for Macintosh (GraphPad Software, Inc.). A repeated measures one-way ANOVA, with Bonferroni post-hoc tests, was used to determine statistical significance between groups. Percent lesion size and midline fiber crossing was compared for the two groups using a Student's t-test. A correlation between the final reaching task success score and the crossing fiber index was determined with a Pearson's correlation. For all analyses, a p value less than 0.05 was considered significant. All data are presented as means +/- standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Our behavioral results showed that the Stroke + hABM-SC group and the Stroke + vehicle control group had statistically similar one week post-stroke deficits (p > 0.05, Figure 1E). However, as early as 4 weeks following MCAO, the Stroke + hABM-SC treated animals had a significantly higher success score than the Stroke + Vehicle Controls (p < 0.05, Figure 1E), which continued throughout the ten weeks of testing. Additionally, Stroke + hABM-SC animals achieved a value of 80% of their baseline values, while Stroke + Vehicle Controls only recovered to 36% of their baseline value, consistent with the limited spontaneous functional recovery as seen in other studies of stroke recovery (Papadopoulos, et al., 2002, Seymour, et al., 2005, Tsai, et al., 2007). Therefore, hABM-SC therapy promoted improved behavioral performance on the skilled forelimb reaching task after stroke.

Inspection of the lesion site showed that the MCAO resulted in ischemic lesions of the ipsilateral sensorimotor cortex in both groups, with no difference in the lesion size. Therefore, hABM-SC therapy did not appear to alter stroke lesion size (Fig 1 F,G).

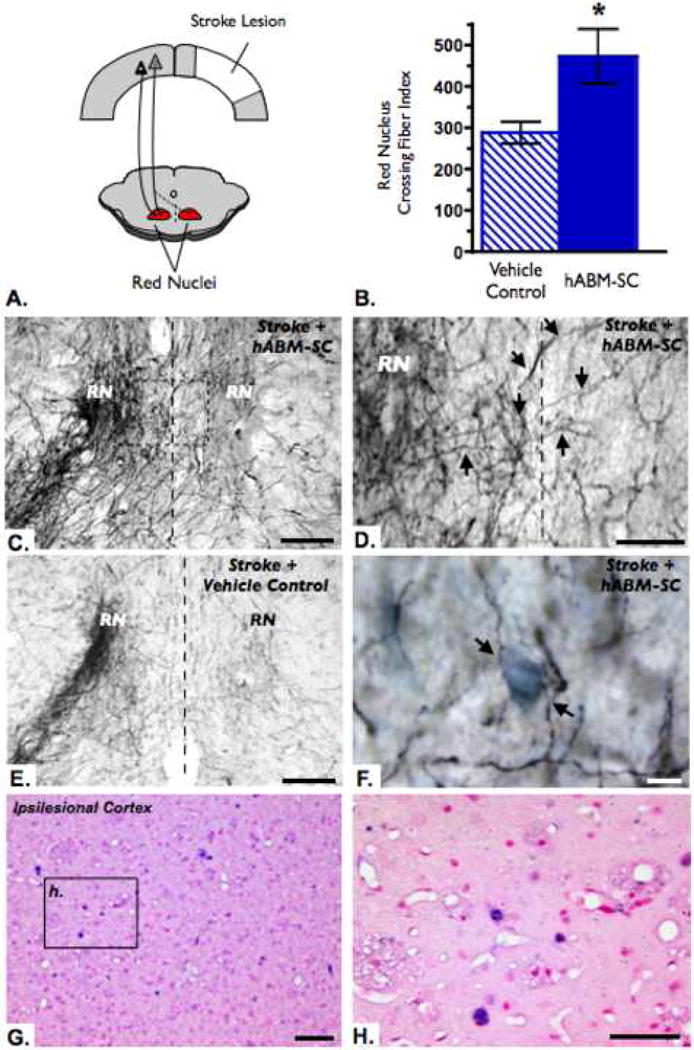

Analysis of BDA-positive fibers showed that in the Stroke + hABM-SC group significantly more fibers crossed the midline at the level of the red nucleus than the Stroke + vehicle control group (Figure 2B) with more terminations in the deafferented red nucleus (Figure 2C-E) and in close proximity to neuronal cell bodies (Figure 2F). A Pearson's correlation determined that there was a significant positive relationship between the fiber crossing index and the final behavioral success score for each animal (p = 0.0325 with R = 0.4437 and R2 = 0.1969).

Fig. 2.

hABM-SC therapy promotes neuronal plasticity from spared contralateral corticorubral tract. (A) Schematic diagram depicts the normal corticorubral tract with fibers terminating in the ipsilateral red nucleus (solid line) as well as new fibers innervating the contralateral red nucleus (dashed line). (B) The number of fibers crossing the midline 12 weeks after stroke were normalized to the total number of fibers labeled with BDA in the cortico-efferent pathways. Quantification of the number of labeled fibers crossing the midline at the level of the red nucleus revealed a significant increase in the hABM-SC group as compared to the vehicle control group (student's t-test, * p < 0.05, error bars indicate standard error). (C) Bilateral projections in the red nucleus of a hABM-SC treated rat, showing many fibers crossing at the midline (dashed line). (D) Higher magnification of the box in (C). BDA-positive fibers (as indicated with arrows) cross the midline (dashed line) to terminate in the contralateral red nucleus. (E) In contrast, the control group shows mainly ipsilateral projection of the corticorubral tract, with few fibers crossing the midline at the level of the red nucleus. (F) Higher magnification of a hABM-SC treated aminal demonstrating BDA-positive fibers with terminations in close proximity to Nissl stained cell bodies. Scale bars (C), (E)= 100 microns, (D) = 50 microns, (F) = 10 microns. (G-H) Human Alu-positive hABM-SCs are present in the ipsilesional cortex 30 days post transplantation. In situ hybridization for human Alu sequence represented by dark purple nuclei, counterstained with nuclear fast red, dark pink nuclei. Scale bars (G) = 50 μm; (H) = 25 μm.

Discussion

The coordination and execution of skilled forelimb and digit movements in the normal rat is dependent on cortico-efferent pathways, including the corticorubral and corticospinal pathways (Iwaniuk and Whishaw, 2000, Metz and Whishaw, 2000). Damaging the motor cortex significantly affects the performance of skilled movements in the forelimb contralateral to the lesion, resulting in permanent deficits from which animals never completely recover (Castro, 1972, Castro, et al., 1977, Whishaw, 2000, Whishaw and Kolb, 1988). In contrast, our results showed that animals treated with hABM-SCs one week after stroke had restored skilled forelimb and digit function to approximately 80% of baseline performance. In support of our work, others have shown functional recovery on gross motor skills when using a similar therapeutic modality of MSC treatment after stroke in the rat (Chen, et al., 2004, Chen, et al., 2003, Chopp and Li, 2002, Li, et al., 2002, Zhang, et al., 2004, Zhao, et al., 2002).

We found that hABM-SC therapy following stroke did not result in a decrease in stroke lesion size or apparent neuronal replacement into the lesion site. Our finding of no change in lesion size is consistent with other studies using MSC therapies following stroke, in that one week delayed administration of the cells did not result in reduced lesion volume after transplantation (Chen, et al., 2000, Zhang, et al., 2004, Zhao, et al., 2002). Therefore, functional recovery in skilled forelimb movements as seen in our study is not thought to be due to new neuron formation or functional integration of the transplanted cells into the lesion site.

The cortico-rubral pathway is mainly an ipsilateral projection from the sensorimotor cortex to the parvocellular red nucleus, with minor contralateral connections. In this study, the number of corticorubral projections from the unlesioned hemisphere that crossed the midline and terminated in the parvocellular portion of the red nucleus were increased with hABM-SC therapy after stroke. The hABM-SC treated rats had nearly double the number of crossing fibers at the level of the red nucleus as compared to the vehicle control treated rats twelve weeks after stroke. Furthermore, the amount of fibers crossing at the red nucleus was positively correlated with functional outcome, suggesting that the uninjured cortex influences recovery of function after stroke and hAMB-SC therapy. In support of this, forelimb functional improvement after CNS lesions has been attributed to neuroanatomical plasticity of uninjured pathways when using various treatments (Papadopoulos, et al., 2002, Raineteau, et al., 2001, Thallmair, et al., 1998, Z'Graggen, et al., 1998), including MSC therapy (Liu, et al., 2007).

In the bone marrow, MSC provide growth factors, structure and various components of the extracellular matrix, that together form the framework for hematopoiesis (Caplan and Bruder, 2001). Interestingly, when certain MSCs are subjected to different tissue environments in vitro, they adapt their expression profile to match the tissue type (Shim, et al., 2004, Shim, et al., 2004, Woodbury, et al., 2000). Similarly, in vivo studies have shown that when MSCs are transplanted into various tissues, they adopt expression characteristics of the host tissue (Jiang, et al., 2002, Mangi, et al., 2003, Min, et al., 2002, Shake, et al., 2002). Pertinent to our work, when MSCs are exposed to injured CNS tissue (both in vitro or in vivo), the MSCs secrete or express growth factors important for axonal growth and neuronal survival (Chen, et al., 2003, Li, et al., 2002, Zhang, et al., 2006, Zhang, et al., 2004). The hABM-SCs used in this study express many pro-regenerative growth factors in vitro, including nerve growth factor (NGF), monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP-1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), stromal cell-derived factor (SDF), stem cell factor (SCF), brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Himes, et al., 2006). Furthermore, we observed hABM-SCs survival in both the ipsilesional and contralesional cortex for at least 30 days post transplantation (Fig 2G-H), thereby allowing for the possible secretion of growth factors throughout the brain. While the mechanism for axonal plasticity after stroke and MSC therapy is not well understood, the neuronal growth promoting properties of MSCs may play an important role which is currently under investigation.

In conclusion, the present study shows that hABM-SCs given one week after ischemic stroke in the adult rat result in behavioral recovery on a skilled forelimb reaching task, which correlates with axonal plasticity from the intact, uninjured hemisphere. Importantly, hABM-SC as used in this studyare derived from a single bone marrow donor, thereby, making them a potentially translational therapy for the treatment of stroke and related disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs (GLK), the Illinois Department of Public Health/Illinois Regenerative Medicine Institute (GLK), NIH grant NINDS 40960 (GLK), Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA) Grant 5F31NS047012-03 (EMA) and Neuronyx, Inc. (GLK), Neuroscience Institute, Loyola University Chicago.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Caplan AI, Bruder SP. Mesenchymal stem cells: building blocks for molecular medicine in the 21st century. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:259–264. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castro AJ. The effects of cortical ablations on digital usage in the rat. Brain Res. 1972;37:173–185. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90665-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castro AJ, Clegg DA, Mc CJ. The effect of large unilateral cortical lesions on rubrospinal tract sprouting in newborn rats. Am J Anat. 1977;149:39–46. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001490104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheatwood JL, Emerick AJ, K GL. Neuronal Plasticity and Functional Recovery after Ischemic Stroke. Top Stroke Rehabilitation. 2008;15:9. doi: 10.1310/tsr1501-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J, Li Y, Chopp M. Intracerebral transplantation of bone marrow with BDNF after MCAo in rat. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:711–716. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Li Y, Wang L, Lu M, Zhang X, Chopp M. Therapeutic benefit of intracerebral transplantation of bone marrow stromal cells after cerebral ischemia in rats. J Neurol Sci. 2001;189:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00557-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J, Li Y, Zhang R, Katakowski M, Gautam SC, Xu Y, Lu M, Zhang Z, Chopp M. Combination therapy of stroke in rats with a nitric oxide donor and human bone marrow stromal cells enhances angiogenesis and neurogenesis. Brain Res. 2004;1005:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J, Zhang ZG, Li Y, Wang L, Xu YX, Gautam SC, Lu M, Zhu Z, Chopp M. Intravenous administration of human bone marrow stromal cells induces angiogenesis in the ischemic boundary zone after stroke in rats. Circ Res. 2003;92:692–699. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000063425.51108.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chopp M, Li Y. Treatment of neural injury with marrow stromal cells. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:92–100. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Digirolamo CM, Stokes D, Colter D, Phinney DG, Class R, Prockop DJ. Propagation and senescence of human marrow stromal cells in culture: a simple colony-forming assay identifies samples with the greatest potential to propagate and differentiate. Br J Haematol. 1999;107:275–281. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzenbach RR, Schwab ME. Disinhibition of neurite growth to repair the injured adult CNS: Focusing on Nogo. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7170-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goshima J, Goldberg VM, Caplan AI. The osteogenic potential of culture-expanded rat marrow mesenchymal cells assayed in vivo in calcium phosphate ceramic blocks. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991:298–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Himes BT, Neuhuber B, Coleman C, Kushner R, Swanger SA, Kopen GC, Wagner J, Shumsky JS, Fischer I. Recovery of function following grafting of human bone marrow-derived stromal cells into the injured spinal cord. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2006;20:278–296. doi: 10.1177/1545968306286976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwaniuk AN, Whishaw IQ. On the origin of skilled forelimb movements. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:372–376. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang Q, Zhang RL, Zhang ZG, Knight RA, Ewing JR, Ding G, Lu M, Arniego P, Zhang L, Hu J, Li Q, Chopp M. Magnetic resonance imaging characterization of hemorrhagic transformation of embolic stroke in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:559–568. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200205000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Chen J, Chen XG, Wang L, Gautam SC, Xu YX, Katakowski M, Zhang LJ, Lu M, Janakiraman N, Chopp M. Human marrow stromal cell therapy for stroke in rat: neurotrophins and functional recovery. Neurology. 2002;59:514–523. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.4.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Z, Li Y, Qu R, Shen L, Gao Q, Zhang X, Lu M, Savant-Bhonsale S, Borneman J, Chopp M. Axonal sprouting into the denervated spinal cord and synaptic and postsynaptic protein expression in the spinal cord after transplantation of bone marrow stromal cell in stroke rats. Brain Res. 2007;1149:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maestre-Moreno JF, Fernandez-Perez MD, Arnaiz-Urrutia C, Minguez A, Navarrete-Navarro P, Martinez-Bosch J. Thrombolysis in stroke: inappropriate consideration of the ‘window period’ as the time available. Rev Neurol. 2005;40:274–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mangi AA, Noiseux N, Kong D, He H, Rezvani M, Ingwall JS, Dzau VJ. Mesenchymal stem cells modified with Akt prevent remodeling and restore performance of infarcted hearts. Nat Med. 2003;9:1195–1201. doi: 10.1038/nm912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Metz GA, Whishaw IQ. Skilled reaching an action pattern: stability in rat (Rattus norvegicus) grasping movements as a function of changing food pellet size. Behav Brain Res. 2000;116:111–122. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Min JY, Sullivan MF, Yang Y, Zhang JP, Converso KL, Morgan JP, Xiao YF. Significant improvement of heart function by cotransplantation of human mesenchymal stem cells and fetal cardiomyocytes in postinfarcted pigs. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:1568–1575. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03952-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papadopoulos CM, Tsai SY, Alsbiei T, O'Brien TE, Schwab ME, Kartje GL. Functional recovery and neuroanatomical plasticity following middle cerebral artery occlusion and IN-1 antibody treatment in the adult rat. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:433–441. doi: 10.1002/ana.10144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raineteau O, Fouad K, Noth P, Thallmair M, Schwab ME. Functional switch between motor tracts in the presence of the mAb IN-1 in the adult rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6929–6934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111165498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sensebe L, Li J, Lilly M, Crittenden C, Herve P, Charbord P, Singer JW. Nontransformed colony-derived stromal cell lines from normal human marrows. I. Growth requirement and myelopoiesis supportive ability. Exp Hematol. 1995;23:507–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seymour AB, Andrews EM, Tsai SY, Markus TM, Bollnow MR, Brenneman MM, O'Brien TE, Castro AJ, Schwab ME, Kartje GL. Delayed treatment with monoclonal antibody IN-1 1 week after stroke results in recovery of function and corticorubral plasticity in adult rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005 doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shake JG, Gruber PJ, Baumgartner WA, Senechal G, Meyers J, Redmond JM, Pittenger MF, Martin BJ. Mesenchymal stem cell implantation in a swine myocardial infarct model: engraftment and functional effects. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1919–1925. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03517-8. discussion 1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shim JW, Koh HC, Chang MY, Roh E, Choi CY, Oh YJ, Son H, Lee YS, Studer L, Lee SH. Enhanced in vitro midbrain dopamine neuron differentiation, dopaminergic function, neurite outgrowth, and 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridium resistance in mouse embryonic stem cells overexpressing Bcl-XL. J Neurosci. 2004;24:843–852. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3977-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shim WS, Jiang S, Wong P, Tan J, Chua YL, Tan YS, Sin YK, Lim CH, Chua T, Teh M, Liu TC, Sim E. Ex vivo differentiation of human adult bone marrow stem cells into cardiomyocyte-like cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thallmair M, Metz GA, Z'Graggen WJ, Raineteau O, Kartje GL, Schwab ME. Neurite growth inhibitors restrict plasticity and functional recovery following corticospinal tract lesions. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:124–131. doi: 10.1038/373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, Howard VJ, Rumsfeld J, Manolio T, Zheng ZJ, Flegal K, O'Donnell C, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, Goff DC, Jr, Hong Y, Adams R, Friday G, Furie K, Gorelick P, Kissela B, Marler J, Meigs J, Roger V, Sidney S, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wilson M, Wolf P. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2006;113:e85–151. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.171600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai SY, Markus TM, Andrews EM, Cheatwood JL, Emerick AJ, Mir AK, Schwab ME, Kartje GL. Intrathecal treatment with anti-Nogo-A antibody improves functional recovery in adult rats after stroke. Exp Brain Res. 2007;182:261–266. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whishaw IQ. Loss of the innate cortical engram for action patterns used in skilled reaching and the development of behavioral compensation following motor cortex lesions in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:788–805. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whishaw IQ, Kolb B. Sparing of skilled forelimb reaching and corticospinal projections after neonatal motor cortex removal or hemidecortication in the rat: support for the Kennard doctrine. Brain Res. 1988;451:97–114. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90753-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woodbury D, Schwarz EJ, Prockop DJ, Black IB. Adult rat and human bone marrow stromal cells differentiate into neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:364–370. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000815)61:4<364::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Z'Graggen WJ, Metz GA, Kartje GL, Thallmair M, Schwab ME. Functional recovery and enhanced corticofugal plasticity after unilateral pyramidal tract lesion and blockade of myelin-associated neurite growth inhibitors in adult rats. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4744–4757. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04744.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang C, Li Y, Chen J, Gao Q, Zacharek A, Kapke A, Chopp M. Bone marrow stromal cells upregulate expression of bone morphogenetic proteins 2 and 4, gap junction protein connexin-43 and synaptophysin after stroke in rats. Neuroscience. 2006;141:687–695. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Li Y, Chen J, Yang M, Katakowski M, Lu M, Chopp M. Expression of insulin-like growth factor 1 and receptor in ischemic rats treated with human marrow stromal cells. Brain Res. 2004;1030:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao LR, Duan WM, Reyes M, Keene CD, Verfaillie CM, Low WC. Human bone marrow stem cells exhibit neural phenotypes and ameliorate neurological deficits after grafting into the ischemic brain of rats. Exp Neurol. 2002;174:11–20. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]