Abstract

Background

Research has shown network social capital associated with a range of health behaviours and conditions. Little is known about what social capital inequalities in health represent, and which social factors contribute to such inequalities.

Methods

Data come from the Montreal Neighbourhood Networks and Healthy Aging Study (n=2707). A position generator was used to collect network data on social capital. Health outcomes included self-reported health (SRH), physical inactivity, and hypertension. Social capital inequalities in low SRH, physical inactivity, and hypertension were decomposed into demographic, socioeconomic, network and psychosocial determinants. The percentage contributions of each in explaining health disparities were calculated.

Results

Across the three outcomes, higher educational attainment contributed most consistently to explaining social capital inequalities in low SRH (% C=30.8%), physical inactivity (15.9%), and hypertension (51.2%). Social isolation, contributed to physical inactivity (11.7%) and hypertension (18.2%). Sense of control (24.9%) and perceived cohesion (11.5%) contributed to low SRH. Age reduced or increased social capital inequalities in hypertension depending on the age category.

Conclusions

Interventions that include strategies to reduce socioeconomic inequalities and increase actual and perceived social connectivity may be most successful in reducing social capital inequalities in health.

Keywords: SOCIAL CAPITAL, SOCIAL INEQUALITIES, Health inequalities, SOCIAL EPIDEMIOLOGY

Introduction

Network social capital refers to the actual or potential resources to which individuals and potentially groups have access through their social networks.1 Network social capital is an emergent property of interpersonal relations and network structures with its health benefits accruing to individuals. Most studies of network social capital and health have examined its association with average population health. Research has shown that people with more diverse and a broader range of network social capital, hereafter social capital, tend to have health-beneficial behaviours and better health status.2 For example, high network capital has been shown associated with physical inactivity,3 obesity,4 better self-reported health (SRH),5–8 and lower chances of depressive symptoms.8 9 Little is known about the factors contributing to social capital inequalities in health.

Social capital inequalities in health represent systematic variations in health resulting from the differential availability or accessibility of network resources. Social capital inequalities arise from capital and return deficits.10 Capital deficit refers to the relative shortage of social capital in one group compared to another.10 For example, persons with lower education may have access to a lower quantity and quality of network resources than those with higher education. Return deficit refers to the process in which capital generates a differential health return for members of different social groups. For example, if groups with less social capital tend to be more physically inactive, capital deficit may contribute to the generation of a health deficit. Determinants with high capital and return deficits will contribute the most to explaining social capital inequalities in health.

What are the underlying determinants of social capital inequalities in health? The following study decomposes social capital inequalities in low SRH, physical inactivity and hypertension into their demographic, socioeconomic, social network and psychosocial determinants. Identifying the degree to which different social characteristics impact health inequalities may lead to interventions that are better adapted to address the needs of vulnerable social groups.

Methods

Study design

Data came from the 2008 Montreal Neighbourhood Networks and Healthy Aging Study (MoNNET-HA). Ethics approval for the study was given by the Committee of Scientific Evaluation and Research Ethics of the Centre de Recherche at the Centre Hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal (CHUM) (N.D. 07.049). The MoNNET-HA study used a two-stage stratified cluster sampling design. In stage 1, Montreal Metropolitan Area census tracts (n=862) were stratified using 2001 Canada Census data into tertiles of high, medium and low household income. From each tertile, 100 census tracts were selected from each tertile (nj=300). In stage 2, potential respondents within each tract were stratified into three age groups: 25–44, 45–64 and 65 years or older. Three respondents were randomly selected within each age stratum and census tract for a total of nine respondents per tract, except for seven tracts in which four participants were selected (ni=2707). To be selected, individuals had to (1) be non-institutionalised, (2) have resided at their current address for at least 1 year, and (3) able to complete the questionnaire in French or English. Random digit dialling of listed telephone numbers was used to select households and a computer-assisted telephone interviewing system guided questionnaire administration. Participants completed the telephone interview between June and early August 2008. The MoNNET-HA response rate was 38.7%. To assess the sample's representativeness, χ2 analyses were used to compare the sample to a range of 2006 Canada census variables. Results showed that the MoNNET-HA sample over-represented females, households with an income less than $C50 000 per year, persons who lived in their current residence for more than 5 years, and those with more than a high school degree.

Measures

Health and health behavioural outcomes

Inequalities in three health outcomes were assessed: (1) low SRH, (2) physical inactivity and (3) hypertension. Low SRH was assessed by asking the question: ‘Generally speaking, would you say that your current health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?’ Responses were dichotomised into low (good, fair, and poor) and high (excellent and very good) categories. Physical inactivity was evaluated using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ).11 The IPAQ converts self-reported physical activity behaviour into metabolic equivalent task (MET) values. IPAQ guidelines were used to classify respondents into high (minimum 3000 MET-min/week), moderate (minimum 600 MET-min/week), and inactive (<600 MET-min/week) physical activity levels. Additional information about the MoNNET-HA IPAQ can be found elsewhere.3 For hypertension, participants reported if a doctor had previously diagnosed them with hypertension.

Network social capital

The MoNNET-HA position generator assessed social capital by asking participants whether they knew someone on a first-name basis working in a range of 10 occupations.7 These occupations were assigned prestige values.12 Social capital was measured along three dimensions: (1) reachability (ie, the highest prestige occupation that a person accessed), (2) diversity (ie, the number of different occupations accessed), and (3) range (ie, the difference between the highest and lowest prestige occupation accessed).10 Due to high correlation among dimensions, principal components analysis was used to create a social capital score, with range contributing the greatest value (0.69). Further information about the MoNNET position generator can be found elsewhere.7 For the decomposition analyses, the social capital score was divided into quintiles.

Demographic characteristics

Sociodemographic factors included gender, age and primary household language. Participants identified their gender. Participants’ were grouped into six age categories: 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74 and 75 years or more, with the youngest age group used as the reference. Respondents identified the primary household language as French, English, or other, with French used as the referent.

Socioeconomic characteristics

Participants selected their household income from five Canadian dollar categories: less than $C28 000, $C28 000–$C49 000, $C50 000–$C74 000, $C75 000–$C100 000 and more than $C100 000. Roughly 20% of participants declined to provide income data. Income was imputed for these respondents using ordinal regression and participant data (1) on sociodemographic variables, including education, age and employment status and (2) Canada census data on median household income for the census tract in which they resided. To assess educational attainment, participants were grouped into those with (1) no high school degree or certificate, (2) a high school diploma or trade certificate, (3) a college certificate or diploma below bachelor's degree, or (4) a bachelor's degree or higher. Participants were asked whether they were currently employed or not.

Social network characteristics

Three social network characteristics were assessed: social isolation, social participation and marital status. Social isolation was based on whether participants reported having or not having discussed important matters with anyone within the last 6 months. For social participation, participants were asked whether they had been members or officials of any community, professional, or other voluntary associations over the past year. Marital status was based on whether participants reported being (1) married or common law status, (2) separated, (3) divorced, (4) widowed, or (5) single. Being married or in a common-law relationship was used as the referent.

Psychosocial characteristics

Psychosocial determinants included generalised trust, perceived cohesion and perceived control. Generalised trust was assessed using the question: ‘Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can't be too careful in dealing with people?’ Participants who replied ‘most people can be trusted’ were considered as having high trust; those who replied with ‘you can't be too careful, depends, most people cannot be trusted’, or ‘don't know’, were considered to have low trust.

Perceived cohesion was assessed using the items: (1) ‘you have trouble with your neighbours’ (2) ‘people in your neighbourhood can be trusted’ (3) ‘people in your neighbourhood are willing to help each other’ (4) ‘most people in your neighbourhood know you’ and (5) ‘your neighbourhood is clean.’ Responses were on a 5-point Likert scale from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’ with ‘don't know’ responses kept as the neutral category. Responses were reverse coded with the exception of item one, and centred on the neutral category so that higher numbers indicated greater perceived cohesion. The perceived cohesion scale had a reliability of 0.55.

Perceived control reflected a person's external orientation, and was measured using four items from Mirowsky's and Ross’ control scale.13 These items were (1) ‘I am responsible for my own successes’ (2) ‘the really good things that happen to me are mostly luck’ (3) ‘I can do just about anything I set my mind to’ and (4) ‘there's no sense planning a lot—if something good is going to happen it will.’ Responses were on a 5-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree with ‘don't know’ responses used as the neutral category. Items one and four were reverse coded. Higher control values indicated greater internal control. The scale was developed to cancel agreement bias, thereby increasing validity.14 The control scale had a reliability of 0.36. Ancillary analyses assessed the impact of the reliability of the control and perceived cohesion scales on findings.

Analysis

Decomposition methods were developed in health economics and have become increasingly accepted in public health and epidemiology as means of assessing health inequality.15–21 Such methods decompose overall inequality (in this case social capital) into the inequality in each of the contributing determinants (eg, education) weighted by the strength of that determinant's association with the health outcome. Conventionally, decomposition methods have been used to assess income-related inequality in health. Our analyses decompose social capital-related inequalities in health, and identify the degree to which social and psychosocial determinants contribute to these inequalities. For a determinant to explain social capital inequalities in health, the determinant must be unequally distributed by social capital and significantly associated with the health indicator.16

To compare inequalities across three health outcomes, observations missing information on the three outcomes, social capital, or factors were dropped. Separate decomposition analyses were conducted for low SRH, physical inactivity and hypertension in several steps.17 18 First, the mean values of each outcome and determinants were calculated, along with the mean values of each outcome for each social capital quintile. Second, the relative (RCI) and absolute concentration indices (ACI) were calculated along with the concentration curves for each health outcome. Relative concentration curves graph the cumulative proportions of the population ranked from the lowest to highest social capital against the cumulative proportions of those having low SRH, PI, or hypertension, thereby summarising relative inequality across the entire distribution of social capital.18 The RCI is twice the area between the concentration curve and the line of equality, or the 45○ diagonal.16 The index ranges from −1 to 1, with 0 representing complete equality.16 The ACI was calculated by multiplying the RCI by the mean level of the health outcome.18 With dichotomous outcomes, the maximum value of the concentration index is bounded by the outcome's prevalence.20 Normalised indices were thus calculated for each outcome by dividing the concentration index by 1-μ, where μ is the mean of the outcome.20 To facilitate comparison, the ACI was selected as the preferred measure of inequality. For poor health indicators, such as physical inactivity, negative ACI values indicated that the determinant held a social capital deficit.

Third, using probit models, each health outcome was then regressed on all the demographic, social and psychosocial determinants. Regression coefficients and 95% CIs were reported for each determinant. Fourth, the absolute contribution of each determinant to explaining health inequality was calculated by multiplying the variable's health elasticity by the determinant's ACI.15 Variable elasticity was a product of the determinant's regression coefficient and the ratio of the determinant's mean over the mean of the health outcome.15

Finally, the percentage contribution (%C) of each determinant was calculated by dividing its absolute contribution by the CI of the health outcome.17 For low SRH, physical inactivity and hypertension, a positive percentage contribution meant that the determinant increased social capital inequality in health, thereby favouring those rich in social capital. Negative contributions meant that the determinant decreased social capital inequality in health in favour of those poor in social capital.

Results

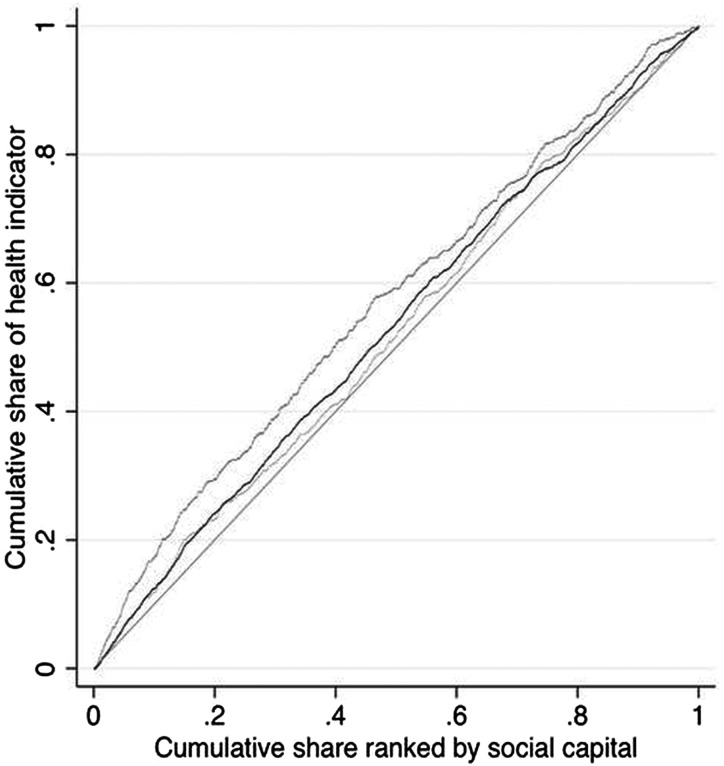

After excluding observations missing variable information, the final sample size was 2616. Table 1 conveys the sample characteristics. In the sample, 44.8% reported low SRH, 16.9% were physically inactive, and 24.3% reported being diagnosed with hypertension. The concentration curves for low SRH, physical inactivity and hypertension are shown in figure 1. Table 2 provides the concentration index values and the means of the health outcomes by social capital quintile. The ACI for low SRH, physical inactivity and hypertension were –0.03, –0.03 and –0.01, respectively, indicating that low SRH, physical inactivity and hypertension were more concentrated in those with low social capital.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Montreal Neighbourhood Networks and Healthy Aging Study (MoNNET-HA) 2008, Social capital inequalities decomposition analysis, n=2616

| Variables | % |

|---|---|

| Health indicators | |

| Low self-reported health (SRH) | 44.8 |

| Physically inactive | 16.9 |

| Having self-reported hypertension | 24.3 |

| Female | 64.9 |

| Age group | |

| 25–34 years old | 14.7 |

| 35–44 years old | 17.8 |

| 45–54 years old | 20.2 |

| 55–64 years old | 16.2 |

| 65–74 years | 21.0 |

| 75 years and more | 10.1 |

| Household language | |

| French (bilingual) | 77.9 |

| English | 13.8 |

| Other | 8.3 |

| Income | |

| Less than $C28 000 | 20.1 |

| $C28 000–$C49 000 | 28.4 |

| $C50 000–$C74 000 | 27.0 |

| $C75 000–$C100 000 | 13.0 |

| More than $C100 000 | 11.5 |

| Education | |

| Less than a high school degree | 11.9 |

| High school degree or trade certificate | 29.1 |

| College certificate | 20.7 |

| Bachelors degree and higher | 38.3 |

| Employed | 54.9 |

| Social isolation | 13.3 |

| High participation | 47.1 |

| Marital status | |

| Married/common-law relationship | 54.4 |

| Single | 20.4 |

| Separated | 4.2 |

| Divorced | 10.8 |

| Widowed | 10.2 |

| High generalised trust | 42.7 |

| Mean (SD) | |

| Perceived neighbourhood cohesion | 0.77 (0.69) |

| Locus of control | 0.77 (0.61) |

Figure 1.

Concentration curves for physical inactivity (dark grey, greater inequality), hypertension (light grey, lesser inequality) and low SRH (black) with reference line of equality (straight grey line) MoNNET-HA, 2008.

Table 2.

Percentage adults with selected health indicator by social capital quintile, normalised (W) and absolute concentration index (ACI), MoNNET-HA 2008, n=2616

| Ill health outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low SRH | Physical inactivity | Hypertension | |

| Percentage adults with __ by social capital quintile | |||

| SC Quintile 1 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 0.29 |

| SC Quintile 2 | 0.43 | 0.18 | 0.21 |

| SC Quintile 3 | 0.46 | 0.13 | 0.25 |

| SC Quintile 4 | 0.41 | 0.15 | 0.26 |

| SC Quintile 5 | 0.40 | 0.13 | 0.21 |

| Relative concentration index RCI (95% CI) | −0.06 (−0.09 to −0.04) | −0.14 (−0.19 to −0.10) | −0.05 (−0.09 to −0.01) |

| Normalised concentration index, W (95% CI) | −0.03 (−0.05 to −0.02) | −0.12 (−0.16 to −0.08) | −0.03 (−0.06, −0.01) |

| Absolute concentration index×101, ACI (95% CI) | −0.03 (−0.04 to −0.02) | −0.03 (−0.03 to −0.02) | −0.01 (−0.02 to −0.003) |

Table 3 presents the ACIs, regression coefficients, 95% CIs and percentage contributions for each determinant. Among demographic determinants, social capital was in deficit among adults 65 years and older (ACI=−0.02) compared to those who were between 25 and 34 years old. Among socioeconomic determinants, social capital was concentrated in those holding a bachelor's degree or higher (ACI=0.07). Social capital was also concentrated in those who had higher household income and were employed. Among social network determinants, social capital was concentrated in those with high social participation (ACI=0.10) and in deficit in those who were socially isolated (ACI=-0.04). Social capital was also more concentrated in those with higher levels of control (ACI=0.08), greater perceived cohesion (ACI=0.04), and high generalised trust (ACI=0.04).

Table 3.

Absolute concentration indices (ACI), probit regression coefficients (β) with 95% CIs, and percentage contributions (%) for determinants in the decomposition analysis, MoNNET-HA, 2008, n=2616

| Determinants* | ACI | Health Indicators | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low SRH | Physical inactivity | Hypertension | |||||

| β (95% CI) | % | β (95% CI) | % | β (95% CI) | % | ||

| DEMOGRAPHIC | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| 75 years and more | −0.02 | 0.08 (−0.12 to −0.01) | 4.48 | 0.10 (0.01 to 0.19) | 6.39 | 0.47 (0.35 to 0.58) | 61.62 |

| 65–74 years | −0.01 | 0.04 (−0.05 to 0.12) | 1.89 | 0.09 (0.02 to 0.16) | 5.26 | 0.43 (0.33 to 0.52) | 51.93 |

| 55–64 years old | 0.01 | 0.04 (−0.04 to 0.12) | −1.98 | 0.05 (−0.01 to 0.12) | −2.91 | 0.42 (0.32 to 0.51) | −47.81 |

| 45–54 years old | 0.01 | 0.03 (−0.04 to 0.10) | −1.26 | 0.07 (0.01 to 0.13) | −3.39 | 0.25 (0.16 to 0.34) | −24.82 |

| 35–44 years old | 0.01 | 0.03 (−0.04 to 0.10) | −1.02 | 0.05 (−0.01 to 0.12) | −2.15 | 0.09 (−0.00 to 0.18) | −7.25 |

| 25–34 years old (ref.) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| SOCIOECONOMIC | |||||||

| Income | |||||||

| More than $C100 000 | 0.03 | −0.21 (−0.29 to −0.13) | 20.22 | −0.04 (−0.10 to 0.02) | 4.26 | −0.07 (−0.14 to −0.01) | 15.47 |

| $C75 000–$C100 000 | 0.02 | −0.14 (−0.22 to −0.06) | 10.65 | −0.05 (−0.10 to 0.00) | 4.23 | −0.02 (−0.09 to 0.05) | 3.88 |

| $C50 000–$C74 000 | 0.02 | −0.14 (−0.20 to −0.07) | 8.56 | −0.04 (−0.08 to 0.00) | 2.76 | −0.06 (−0.12 to −0.01) | 8.29 |

| $C28 000–$C49 000 | −0.01 | −0.06 (−0.12 to 0.00) | −3.14 | −0.02 (−0.06 to 0.01) | −1.40 | −0.03 (−0.08 to 0.01) | −4.03 |

| Less than $C28 000 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Education | |||||||

| Bachelor's degree and higher | 0.07 | −0.12 (−0.21 to −0.05) | 30.75 | −0.06 (−0.11 to −0.01) | 15.85 | −0.09 (−0.15 to −0.04) | 51.24 |

| College certificate | 0.01 | −0.13 (−0.20 to −0.05) | 2.57 | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.03) | 0.49 | −0.07 (−0.12 to −0.02) | 3.22 |

| High school degree/trade certificate | −0.03 | −0.07 (−0.14 to 0.00) | −8.03 | −0.05 (−0.09 to −0.01) | −6.87 | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.03) | −4.98 |

| Less than a high school degree (ref.) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Employed | 0.04 | −0.07 (−0.12 to −0.01) | 10.32 | −0.05 (−0.09 to −0.01) | 9.00 | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.02) | 8.37 |

| Social network | |||||||

| Social isolation | −0.04 | 0.05 (−0.01 to 0.12) | 8.07 | 0.07 (0.02 to 0.12) | 11.65 | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.10) | 18.15 |

| High participation | 0.10 | −0.02 (−0.06 to 0.01) | 9.37 | −0.03 (−0.05 to −0.01) | 13.59 | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.03) | −0.39 |

| PSYCHOSOCIAL | |||||||

| High generalised Trust | 0.04 | −0.04 (−0.08 to 0.00) | 5.89 | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) | 1.33 | −0.02 (−0.06 to 0.01) | 8.22 |

| Perceived neighbourhood cohesion | 0.04 | −0.08 (−0.11 to −0.05) | 11.50 | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) | 1.26 | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.01) | 3.77 |

| Locus of control | 0.08 | −0.09 (−0.13 to −0.05) | 24.85 | −0.03 (−0.05 to 0.00) | 7.91 | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.04) | −8.05 |

| Residual unexplained | −3.46 | 7.25 | 13.78 | ||||

Values bolded if p<0.05 and percentage contribution is greater than 10%.

*Due to space limitations and lack of significance gender, household language, and marital status were not reported in Table 3. Results available upon request.

Socioeconomic determinants, particularly educational attainment, were the most consistent in their contributions to social capital inequalities across the three health outcomes. Having a bachelor's degree or higher, compared to no high school degree, explained 51.2% of social capital inequalities in hypertension, 30.8% in low SRH and 15.9% in physical inactivity. There was variation in the degree to which social network, psychosocial, demographic, determinants contributed to inequalities in the three outcomes. Social network determinants, mainly social isolation, explained inequalities in physical inactivity (11.7%) and hypertension (18.2%). Psychosocial determinants, specifically control and perceived cohesion, contributed to inequalities in low SRH at 24.9% and 11.5%, respectively. Demographic determinants, specifically age category, contributed the most to explaining social capital inequalities in hypertension. Compared to 25–34 years old participants, being an adult between 45 and 54 (%C=−24.8%) or 55 to 64 years old (%C=−47.8%), reduced inequalities in hypertension. There was, however, a reversal at 65 years of age, in which being in the oldest age groups increased inequalities in hypertension. This reversal was driven by capital deficit in the oldest age groups, and not a shift in the association between age and hypertension.

Discussion

No studies, as far as we are aware, have decomposed social capital inequalities in health into their demographic, socioeconomic, network and psychosocial determinants. Several findings emerge. First, using a network approach to social capital, we found that socioeconomic characteristics provided strong and consistent contributions to explaining social capital inequalities across the three outcomes. Educational inequalities between those with a bachelor's and those without a high school degree contributed the most to explaining social capital inequalities in health. This reflects the importance of social stratification processes in accessing social capital. The higher someone's initial social position, the higher the quality and quantity of resources reached through one's social connections.10

Second, our study showed that network, psychosocial and demographic determinants also explained social capital inequalities in health. The contributions that these other determinants made to social capital inequalities differed according to the particular health outcome. For example, network characteristics, primarily isolation, contributed to social capital inequalities in the behavioural and physiological health indicators. Adults lacking core social connections were disadvantaged in social capital, and were also more likely to be physically inactive or have hypertension. By contrast, psychosocial resources, specifically control and perceived cohesion, contributed to social capital gaps in low SRH. This may reflect the fact that health self-assessment involves a cognitive process more closely tied to one's sense of control and belonging.22 Finally, demographic characteristics, specifically age, contributed to increases and decreases in inequalities in hypertension. Whether age increased or decreased inequalities in hypertension depended on the age group in which a participant fell. Research has shown that the quantity and diversity of a person's social ties tend to increase with age until retirement, at which time social ties begin to decrease in number and diversity.23 24 Since adults older than 65 years held a capital deficit compared to the younger age groups, they experienced an increase rather than a decrease in social capital inequalities in hypertension.

Four limitations are worth noting. First, health outcomes were based on self-reported information and may not fully reflect actual health status. For example, self-reported physical activity measures have been shown to be susceptible to social desirability bias, whereby adults overestimate their physical activity levels.25 Second, the perceived cohesion and control scales had low reliabilities. To assess the impact of their low reliability, ancillary analyses were conducted. Alternative control and perceived cohesion variables were created using principal components analysis. Decomposition analyses were rerun with the alternative psychosocial variables, and compared against findings using the cohesion and control scales to assess whether the scales’ low reliabilities impacted overall results. There was little change in the percentage contributions of these two factors to the social capital inequalities, although control did contribute an additional 5% to inequalities in low SRH in the ancillary analyses. Additional information about the results of these ancillary analyses is available upon request. Third, the level of social capital inequalities in health may seem low compared to income-related inequalities in health. By contrast with individual-level factors, however, social capital inequalities represent interpersonal and structural features that operate at a higher ecological level and generate greater population exposure. Finally, the MoNNET-HA sample is representative of urban-dwelling adults residing in a developed country. Future studies may show that the determinants of social capital inequalities in health may differ in rural or developing country settings.

This study highlights the importance of social stratification and network factors in the generation of social capital inequalities in health. Psychosocial and demographic factors appear to play a greater role with specific types of outcomes. Addressing social capital inequalities in health through population health interventions require multidimensional strategies that aim to reduce socioeconomic inequalities alongside efforts to increase actual and perceived social connectivity.

What is already known on this subject.

Social capital has been associated with a range of health behaviours and conditions. Little is known about the social and psychosocial mechanisms linking social capital with health, and the degree to which these mechanisms explain social capital inequalities in health.

What this study adds.

Socioeconomic factors contribute most consistently to social capital inequalities in health. Social network, psychosocial, and demographic factors play greater or lesser roles depending on the health outcome. To address social capital inequalities in health, interventions should consist of multiple strategies aiming to reduce socioeconomic inequalities alongside efforts to increase actual and perceived social connectivity.

Footnotes

Contributors: SM conceived of the study and led interpretation of results, and writing. SS conducted statistical analyses. AT and SS interpreted findings, assisted in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for intellectual content, and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-84584).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Committee of Scientific Evaluation and Research Ethics of the Centre de Recherche at the Centre Hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal (CHUM) (N.D. 07.049).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bourdieu P. The Forms of Capital. In: Richardson JG. ed. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. New York: Greenwood, 1985:241–58 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Kim D. eds. Social Capital and Health. New York, NY: Springer, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Legh-Jones H, Moore S. Network social capital, social participation, and physical inactivity in an urban adult population. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:1362–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore S, Daniel M, Paquet C, et al. Association of individual network social capital with abdominal adiposity, overweight, and obesity. J Public Health 2009;31:175–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpiano R, Hystad P. “Sense of community belonging” in health surveys: what social capital is it measuring?. Health Place 2011;17:606–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verhaeghe PP, Pattyn E, Bracke P, et al. The association between network social capital and self-rated health: pouring old wine in new bottles. Health Place 2012;18:358–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore S, Bockenholt U, Daniel M, et al. Social capital and core neighbourhood ties: A validation study of individual-level social capital measures of neighbourhood social connections. Health Place 2011;17:536–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song L, Lin N. Social capital and health inequality: evidence from Taiwan. J Health Soc Behav 2009;50:149–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haines V, Beggs JJ, Hurlbert JS. Neighborhood disadvantage, network social capital, and depressive symptoms. J Health Soc Behav 2011;52:58–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) Research Committee. Guidelines for data processing and analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)- Short and long form. 2005. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/scoring-protocol

- 12.Goyder J, Guppy N, Thompson M. The allocation of male and female occupational prestige in an Ontario urban area: A quarter-century replication. Can Rev Sociol Anthropol 2003;40:417–40 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirowsky J, Ross C. Social Causes of Psychological Distress. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Eliminating Defense and Agreement Bias from Measures of the Sense of Control: A 2×2 Index. Soc Psychol Q 1991;54:127–45 [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGrail K, Doorslaer E, Ross N, et al. Income-Related Health Inequalities in Canada and the United States: A Decomposition Analysis. Am J Public Health 2009;99:1856–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Speybroeck N, Konings P, Lynch J, et al. Decomposing socioeconomic health inequalities. Int J Pub Health 2010;55:347–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosseinpoor AR, van Doorslaer E, Speybroeck N, et al. Decomposing socioeconomic inequality in infant mortality in Iran. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:1211–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konings P, Harper S, Lynch J, et al. Analysis of socioeconomic inequalities using the concentration index. Int J Public Health 2009;55:71–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagstaff A, Paci P, Vandoorslaer E. On the Measurement of Inequalities in Health. Soc Sci Med 1991;33:545–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagstaff A. The bounds of the concentration index when the variable of interest is binary, with an application to immunization inequality. Health Econ 2005;14:429–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKinnon B, Harper S, Moore S. Decomposing income-related inequality in cervical screening in 67 countries. Int J Public Health 56:139–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jylhä M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:307–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oh J-H. Assessing the Social Bonds of Elderly Neighbors: The Roles of Length of Residence, Crime Victimization, and Perceived Disorder. Sociol Inq 2003;73:490–510 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoller E, Pugliesi K. Informal Networks of Community-Based Elderly. Res Aging 1988;10:499–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sallis JF, Saelens BE. Assessment of physical activity by self-report: status, limitations, and future directions. Res Q Exerc Sport 2000;71:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]