Abstract

Background

Mutation specific effects in monogenic disorders are rare. We describe atypical Fanconi syndrome caused by a specific heterozygous mutation in HNF4A. Heterozygous HNF4A mutations cause a beta cell phenotype of neonatal hyperinsulinism with macrosomia and young onset diabetes. Autosomal dominant idiopathic Fanconi syndrome (a renal proximal tubulopathy) is described but no genetic cause has been defined.

Methods and Results

We report six patients heterozygous for the p.R76W HNF4A mutation who have Fanconi syndrome and nephrocalcinosis in addition to neonatal hyperinsulinism and macrosomia. All six displayed a novel phenotype of proximal tubulopathy, characterised by generalised aminoaciduria, low molecular weight proteinuria, glycosuria, hyperphosphaturia and hypouricaemia, and additional features not seen in Fanconi syndrome: nephrocalcinosis, renal impairment, hypercalciuria with relative hypocalcaemia, and hypermagnesaemia. This was mutation specific, with the renal phenotype not being seen in patients with other HNF4A mutations. In silico modelling shows the R76 residue is directly involved in DNA binding and the R76W mutation reduces DNA binding affinity. The target(s) selectively affected by altered DNA binding of R76W that results in Fanconi syndrome is not known.

Conclusions

The HNF4A R76W mutation is an unusual example of a mutation specific phenotype, with autosomal dominant atypical Fanconi syndrome in addition to the established beta cell phenotype.

Keywords: Renal Medicine, Calcium and Bone, Clinical Genetics, Diabetes, Metabolic Disorders

Mutations within the same gene can cause different phenotypes. Mutation-specific phenotypes, where a single mutation is associated with a different phenotype, are rare. Activating or inactivating mutations in a single gene can cause opposite phenotypes, as seen in the genes encoding the pancreatic β cell potassium channel subunits where activating mutations cause neonatal diabetes but inactivating mutations cause congenital hyperinsulinism.1 The location of a mutation within a gene can cause different phenotypes, as seen in NOTCH2 where mutations affecting the epidermal growth factor (EGF) repeats and ankyrin repeats (ANK) domain of NOTCH2 cause Alagille syndrome2 [MIM 118450], but those in the terminal exon 34 result in Hajdu–Cheney syndrome3 4 [MIM 102500]. The same mutation can cause a different phenotype according to the patient's age. In HNF4A, there are not mutation-specific phenotypes, but as a result of increased insulin secretion seen in early life, birth weight is increased by 790 g and there is neonatal hypoglycaemia.5 Later in life, diabetes develops (median age 24 years at diagnosis6) due to decreased insulin secretion. No renal phenotype associated with HNF4A mutations has been described, although the knockout mouse of the related transcription factor HNF1A was described as having Fanconi syndrome.7

Fanconi syndrome [MIM 134600] is a generalised dysfunction of the renal proximal tubule in which the genetic aetiology has been described in a variety of syndromes that include Cystinosis [MIM 219800], Lowe syndrome [MIM 309000] or Fanconi-Bickel syndrome [MIM 227810]. As a consequence of proximal tubulopathy, there is failure of resorption of glucose, amino acids, phosphate, low molecular weight proteins, bicarbonate and urate. The usual presenting clinical features are growth failure and rickets in childhood.8 Treatment is based on replacing the lost solutes. Families with autosomal-dominant idiopathic Fanconi syndrome have been reported.9–15 Despite a study showing linkage to chromosome 15 in a single family,16 no genetic cause has been established.

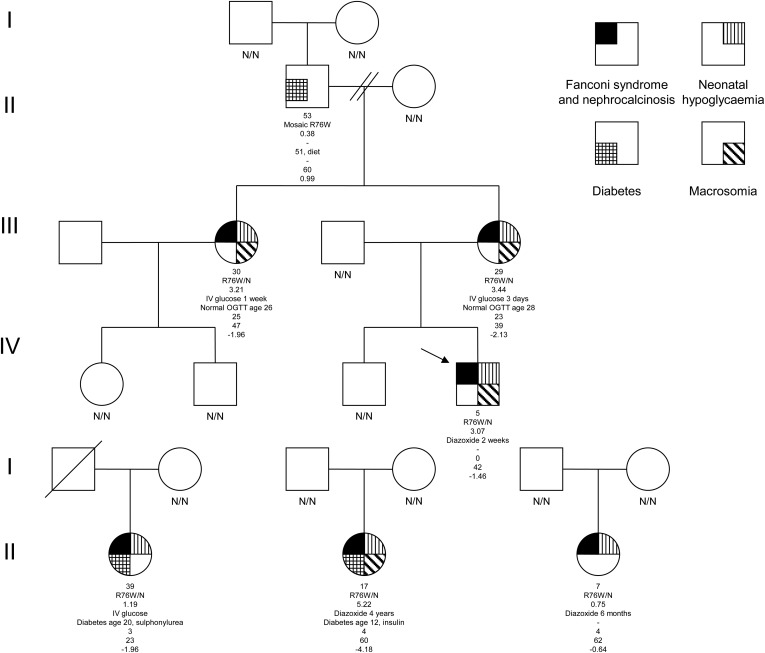

We studied a family with three individuals affected with a similar clinical phenotype of Fanconi syndrome and nephrocalcinosis in addition to neonatal hypoglycaemia and macrosomia (figure 1). Two sisters were diagnosed with Fanconi syndrome due to short stature and rickets. Genetic testing for mutations in the PHEX, FGF23, DMP1, ENPP1 and SLC34A3 genes did not confirm a genetic diagnosis of hypophosphataemic rickets. Urine and serum analysis in these three affected family members demonstrated a full Fanconi syndrome with heavy low molecular weight proteinuria, aminoaciduria, glycosuria and a low serum urate (see online supplementary tables S1 and S2). Additionally, they had nephrocalcinosis diagnosed by renal ultrasound (figure 2B) with atypical biochemical features. One sister gave birth to a macrosomic baby (birth weight >99th centile for gestation) with neonatal hyperinsulinism requiring diazoxide treatment, which was also seen in the sisters (figure 1). These latter features were consistent with an HNF4A mutation, but no HNF4A renal phenotype has previously been described. After informed consent was provided, sequence analysis of the HNF4A gene identified a heterozygous p.R76W mutation (c.226C>T according to the Chartier et al17 cDNA reference sequence, using methods previously described by Flanagan et al18) in the proband, mother and maternal aunt. The mutation had arisen in the proband's maternal grandfather who is a germline and somatic mosaic (26% mutation in leukocyte DNA). This suggested that a novel renal and β cell phenotype cosegregated with the R76W mutation within one family.

Figure 1.

Partial pedigrees. Pedigrees of the four families demonstrate co-segregation of the p.R76W HNF4A mutation with neonatal hypoglycaemia and Fanconi syndrome. The genotype is given below each symbol where known. For each proband, age at follow-up, mutation, birth weight Z score, hypoglycaemia treatment and duration, age of diabetes diagnosis/diabetes management, age of diagnosis of Fanconi syndrome, glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (mLs/min/1.73 m2) and height Z score are provided. The mutation is reported according to the HNF4A cDNA sequence published by Chartier et al17 but has also been described as p.R85W according to reference sequence NM_000457.3 or p.R63W using NM_175914.3 (LRG_483).22 Birth weight and height Z scores are calculated from UK 1990 child growth including standard children and preterm infants. Our proband's grandfather developed diabetes at 51 years of age with a body mass index (BMI) of 30.5. He is managed with weight loss alone with a recent HbA1c of 39 mmol/mol. The mutation was present in his leukocyte DNA at 26% but it is not known if the mutation load in his pancreas is sufficient to cause his diabetes. He had no reported neonatal hypoglycaemia or Fanconi syndrome (data not shown). Neither the proband, his mother, nor her sister are currently diabetic, but they undergo surveillance using an annual oral glucose tolerance test.

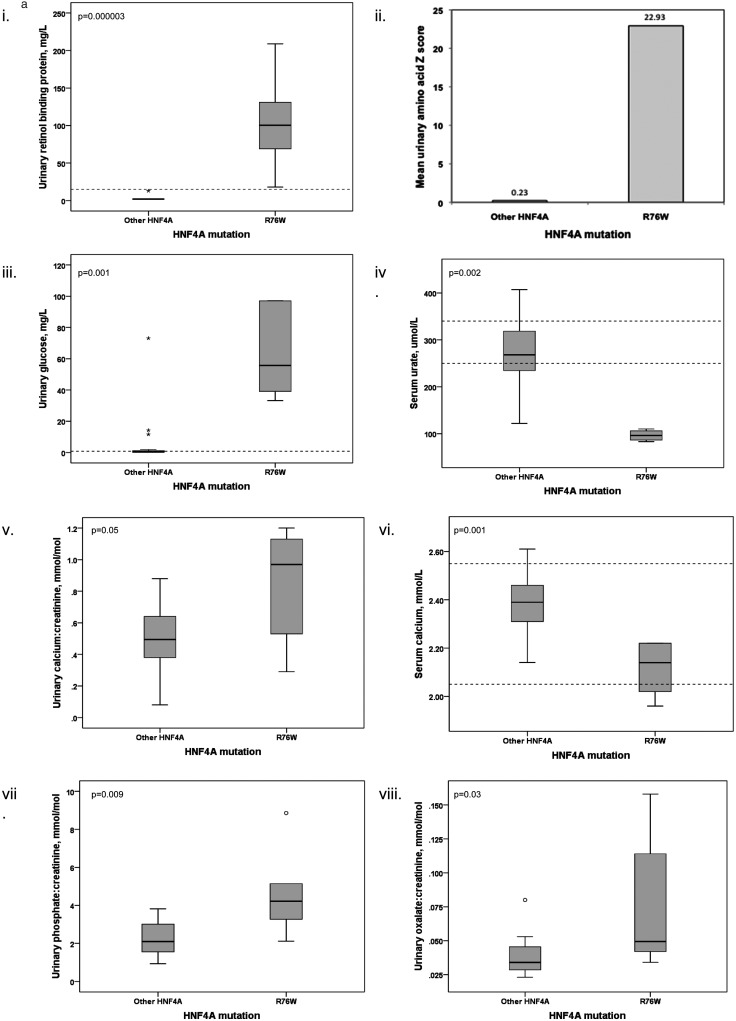

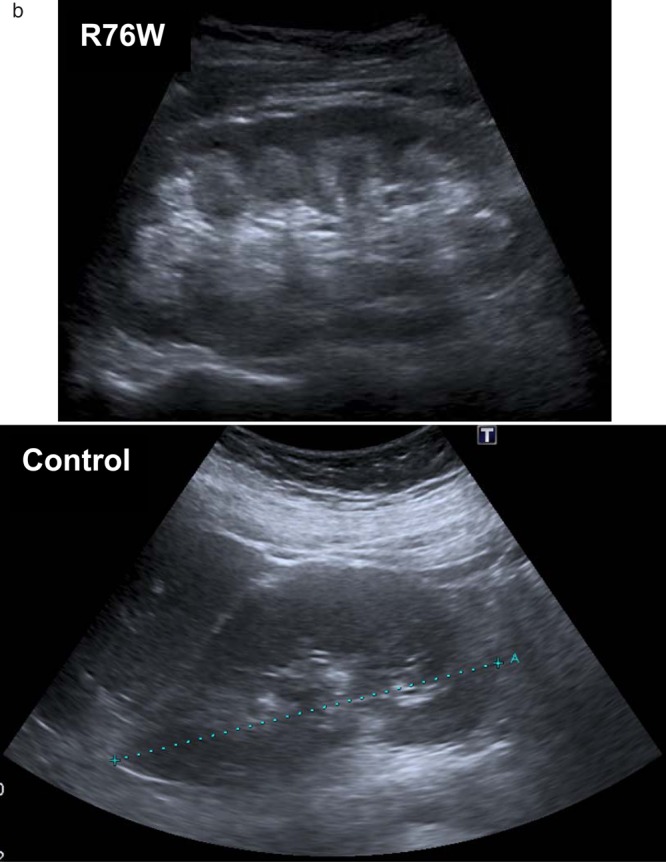

Figure 2.

(A) Boxplots comparing (1) urinary retinol-binding protein, (2) mean urinary amino acid Z scores, (3) urinary glucose, (4) serum urate, (5 and 6) urinary and serum calcium, (7) urinary phosphate and (8) urinary oxalate between R76W mutations and other HNF4A mutations. Boxplots demonstrate the phenotype is mutation specific by comparing patients with the mutation to patients with other HNF4A mutations. We compared analysis of fasted first-void urine and renal ultrasound scans between patients with the R76W mutation and 20 patients with other mutations in HNF4A. Medians were compared using the Mann–Whitney U Test or Fisher's exact test, and a mean urinary amino acid Z score calculated (with control data being derived from laboratory reference ranges). Other HNF4A mutations comprise: S34X, R80Q, A120D, R125W (2), R125Q, V190A, D206Y, R244W, L260P, L263P, E276Q, R303H, R303C, I314F, L332P, delEx1-7, c.466-2A>G, c.1delA, t(3;20)(p21.2;q12). (Laboratory reference ranges are shown with dashed lines (where a single line is present the reference range is below this value).). (B) Renal ultrasonographic images comparing nephrocalcinosis changes to normal kidney. Nephrocalcinosis is demonstrated by increased reflectivity of the renal pyramids, as seen in the top panel (patient heterozygous for R76W), compared to normal ultrasound images in the bottom panel (patient with balanced translocation t(3;20)(p21.2;q12) described by Gloyn et al23).

We sought to examine if other patients with the R76W mutation also had a renal phenotype. We identified three additional patients with the R76W mutation from a cohort of 147 probands with HNF4A mutations (figure 1). All patients had hyperinsulinism and/or macrosomia, and two subsequently developed diabetes. One has been previously published.18 We investigated these patients for the renal phenotype seen in our first family using the methods described above (see online supplementary tables S1 and S2). The additional three patients with the heterozygous p.R76W HNF4A mutation also had a phenotype of Fanconi syndrome and nephrocalcinosis in addition to the pancreatic β cell phenotype. This suggested that the Fanconi syndrome was a consistent feature of the HNF4A R76W mutation.

We went on to establish if patients with other HNF4A mutations also had Fanconi syndrome. We took urine and serum samples from 20 diabetic patients with HNF4A mutations other than R76W and investigated biochemical and radiological features (figure 2A, see online supplementary tables S1 and S2). Our results demonstrate there was a specific phenotype seen in the six patients with the R76W mutation. This includes the classical features of Fanconi syndrome with a urinary leak of low molecular weight proteins, amino acids (mean Z score of urinary amino acids for R76W heterozygotes was 22.9, compared to 0.2 for other mutations (individual amino acid data is shown in online supplementary table S2)), urate, glucose and phosphate. Additionally, there were features not typically seen, of hypercalciuria, hyperoxaluria and hypermagnesaemia. Nephrocalcinosis was present in all patients with the R76W mutation, but no patients with other mutations in the HNF4A gene. The R76W mutation carriers have renal impairment with a median creatinine of 114 μmol/L. These results demonstrate a previously undescribed renal phenotype for the R76W mutation and show that patients with other mutations in HNF4A do not exhibit these specific renal features.

There is a single reported patient outside of our series that has the R76W mutation.19 This patient had features of Fanconi syndrome in addition to neonatal hyperinsulinism. Additional features included hepatomegaly with elevated transaminases at 3 months of age and abundant glycogen on liver biopsy. Renal ultrasound findings were not reported, so nephrocalcinosis cannot be excluded. No patients in our series had hepatosplenomegaly.

The specific phenotype seen with the R76W HNF4A mutation suggests this mutated hepatic transcription factor binds to different target(s). The R76 residue is in the DNA-binding domain and directly contacts the DNA DR1 response element comprised of AGGTCA half sites.20 In functional studies, there was a decrease in DNA binding, but this was not mutation specific.20 Our modelling demonstrates differences in charge and hydrophobicity with the R76W mutation compared to wild type in areas of intimate DNA contact (see online supplementary figure S3). Therefore, the mechanism of the mutation-specific phenotype is likely to involve altered DNA binding, but the details of this and the novel target bound/unbound are not known.

The tubulopathy we see in these patients is a generalised Fanconi syndrome with extended features, which include nephrocalcinosis and alterations in the handling of magnesium, oxalate and calcium, with a subsequent effect on calcium homeostasis. We did not see a significant acidosis which is usually described in Fanconi syndrome. We hypothesise that high urine concentrations of calcium, phosphate and oxalate predispose to renal tract calcification. The renal impairment may reflect damage from calcification, or altered tubular excretion of creatinine. Glycosuria may have a delaying effect on the development of diabetes in these individuals, akin to treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors. The changes we have seen in magnesium handling with both elevated serum and urine levels are intriguing; this appears to be an overflow rather than a leak as seen with calcium, phosphate and urate. Proximal tubular transport is via a variety of mechanisms8: cotransport of glucose, amino acids and phosphate with sodium generates energy for non-sodium ion transport against an electrochemical gradient. Low molecular weight proteins are reabsorbed using the endosomal pathway, and urate handling is through apical URAT1 and luminal GLUT9 and a complex series of organic anion and cation transporters. Calcium resorption is mediated by the paracellular route via the increased potential difference set up by the sodium cotransporters, and 60% of calcium resorption occurs in the proximal tubule. The mechanisms for the generalised dysfunction in Fanconi syndrome remain unsolved, but hypotheses include disturbances in cellular energy metabolism, membrane characteristics and transporters.21 Present understanding of physiology is inadequate to fully explain the extent of the tubulopathy.

In conclusion, we present a novel atypical cause of autosomal-dominant Fanconi syndrome with nephrocalcinosis caused by the HNF4A R76W mutation. This unique mutation-specific phenotype is characterised by increased birth weight, neonatal hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia which may progress to diabetes, and Fanconi syndrome with nephrocalcinosis. It has not been described in patients with other mutations in HNF4A, or other monogenic diabetes genes. This finding provides new insights into the genetic regulation of proximal tubular maturation, as well as the precise renal effects HNF4A gene mutations. In silico modelling suggests a pivotal role for this particular residue in DNA binding, and we hypothesise that the renal phenotype is a consequence of a defective interaction of HNF4A with major regulatory genes. The fact that there are no other mutations in HNF4A that cause this phenotype suggests that this particular residue must be crucial in the renal proximal tubule. In summary, this is an unusual case of a mutation-specific phenotype in HNF4A with a renal Fanconi syndrome and nephrocalcinosis in addition to the previously described β cell phenotype.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients for their participation. We gratefully acknowledge the invaluable assistance of the Medical Technical Officers at the Biochemistry Laboratory, Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust. We kindly thank Lucy Bryant for assistance with figures.

Footnotes

Contributors: AJH collected and analysed the data and co-authored the manuscript. CB is the patient's clinican, supervised the project and co-authored the manuscript. TJM performed laboratory analysis. PRC analysed urine amino acid data. RC performed bioinformatic analysis. MNW performed a literature review. RAO performed statistical analysis and reviewed the manuscript. BNS performed statistical analysis and reviewed the manuscript. MHS contacted patients and reviewed the manuscript. CDI is the proband's clinician and reviewed the manuscript. JPH-S is the proband's clinician and reviewed the manuscript. SE oversaw genetic sequencing and analysis and co-authored the manuscript. ATH supervised the project and co-authored the manuscript.

Funding: This article presents independent research supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Exeter Clinical Research Facility. The research is funded by a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award, (grant number 098395/Z/12/Z). Research materials can be obtained via the corresponding author.

Competing interests: ATH and SE are Wellcome Trust Senior Investigators.

Ethics approval: North and East Devon Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

References

- 1.Sandal T, Laborie LB, Brusgaard K, Eide S, Christesen HBT, Søvik O, Njølstad PR, Molven A. The spectrum ofABCC8mutations in Norwegian patients with congenital hyperinsulinism of infancy. Clin Genet 2009;75:440–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamath BM, Bauer RC, Loomes KM, Chao G, Gerfen J, Hutchinson A, Hardikar W, Hirschfield G, Jara P, Krantz ID, Lapunzina P, Leonard L, Ling S, Ng VL, Hoang PL, Piccoli DA, Spinner NB. NOTCH2 mutations in Alagille syndrome. J Med Genet 2012;49:138–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simpson MA, Irving MD, Asilmaz E, Gray MJ, Dafou D, Elmslie FV, Mansour S, Holder SE, Brain CE, Burton BK, Kim KH, Pauli RM, Aftimos S, Stewart H, Kim CA, Holder-Espinasse M, Robertson SP, Drake WM, Trembath RC. Mutations in NOTCH2 cause Hajdu-Cheney syndrome, a disorder of severe and progressive bone loss. Nat Genet 2011;43:303–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isidor B, Lindenbaum P, Pichon O, Bezieau S, Dina C, Jacquemont S, Martin-Coignard D, Thauvin-Robinet C, Le Merrer M, Mandel JL, David A, Faivre L, Cormier-Daire V, Redon R, Le Caignec C. Truncating mutations in the last exon of NOTCH2 cause a rare skeletal disorder with osteoporosis. Nat Genet 2011;43:306–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearson ER, Boj SF, Steele AM, Barrett T, Stals K, Shield JP, Ellard S, Ferrer J, Hattersley AT. Macrosomia and hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia in patients with heterozygous mutations in the HNF4A gene. PLoS Med 2007;4:e118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harries LW, Locke JM, Shields B, Hanley NA, Hanley KP, Steele A, Njolstad PR, Ellard S, Hattersley AT. The diabetic phenotype in HNF4A mutation carriers is moderated by the expression of HNF4A isoforms from the P1 promoter during fetal development. Diabetes 2008;57:1745–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pontoglio M, Barra J, Hadchouel M, Doyen A, Kress C, Bach JP, Babinet C, Yaniv M. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 inactivation results in hepatic dysfunction, phenylketonuria, and renal Fanconi syndrome. Cell 1996;84:575–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davison AM. Oxford Textbook of Clinical Nephrology. Oxford University Press, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ben-Ishay D, Dreyfuss F, Ullmann TD. Fanconi syndrome with hypouricemia in an adult: family study. Am J Med 1961;31:793–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt DD, Stearns G, McKinley JB, Froning E, Hicks P, Bonfiglio M. Long-Term Study of Family with Fanconi Syndrome without Cystinosis (DeToni-Debre-Fanconi Syndrome)*. Am J Med 1966;40:492–510 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brenton DP, Isenberg DA, Cusworth DC, Garrod P, Krywawych S, Stamp TC. The adult presenting idiopathic Fanconi syndrome. J Inherit Metab Dis 1981;4: 211–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tolaymat A, Sakarcan A, Neiberger R. Idiopathic Fanconi syndrome in a family. Part I. Clinical aspects. J Am Soc Nephrol 1992;2:1310–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wen SF, Friedman AL, Oberley TD. Two case studies from a family with primary Fanconi syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis 1989;13:240–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith R, Lindenbaum RH, Walton RJ. Hypophosphataemic osteomalacia and Fanconi syndrome of adult onset with dominant inheritance. Possible relationship with diabetes mellitus. Q J Med 1976;45:387–400 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman AL, Trygstad CW, Chesney RW. Autosomal dominant Fanconi syndrome with early renal failure. Am J Med Genet 1978;2:225–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lichter-Konecki U, Broman KW, Blau EB, Konecki DS. Genetic and physical mapping of the locus for autosomal dominant renal Fanconi syndrome, on chromosome 15q15.3. Am J Hum Genet 2001;68:264–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chartier FL, Bossu JP, Laudet V, Fruchart JC, Laine B. Cloning and sequencing of cDNAs encoding the human hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 indicate the presence of two isoforms in human liver. Gene 1994;147:269–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flanagan SE, Kapoor RR, Mali G, Cody D, Murphy N, Schwahn B, Siahanidou T, Banerjee I, Akcay T, Rubio-Cabezas O, Shield JP, Hussain K, Ellard S. Diazoxide-responsive hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia caused by HNF4A gene mutations. Eur J Endocrinol 2010;162:987–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanescu DE, Hughes N, Kaplan B, Stanley CA, De Leon DD. Novel presentations of congenital hyperinsulinism due to mutations in the MODY genes: HNF1A and HNF4A. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:E2026–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chandra V, Huang P, Potluri N, Wu D, Kim Y, Rastinejad F. Multidomain integration in the structure of the HNF-4alpha nuclear receptor complex. Nature 2013;495:394–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taal MW, Chertow GM, Marsden PA, Skorecki K, Yu ASL, Brenner BM. Brenner and Rector's The Kidney E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colclough K, Bellanne-Chantelot C, Saint-Martin C, Flanagan SE, Ellard S. Mutations in the genes encoding the transcription factors hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha and 4 alpha in maturity-onset diabetes of the young and hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Hum Mutat 2013;34:669–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gloyn AL, Ellard S, Shepherd M, Howell RT, Parry EM, Jefferson A, Levy ER, Hattersley AT. Maturity-onset diabetes of the young caused by a balanced translocation where the 20q12 break point results in disruption upstream of the coding region of hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha (HNF4A) gene. Diabetes 2002;51:2329–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.