Abstract

Background:

Studies with platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors (GPIs) showed conflicting results in primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) patients who were pretreated with 600 mg clopidogrel. We sought to investigate the short- and long-term efficacy and safety of the periprocedural administration of tirofiban in a largest Serbian PPCI centre.

Methods:

We analysed 2995 consecutive PPCI patients enrolled in the Clinical Center of Serbia STEMI Register, between February 2007 and March 2012. All patients were pretreated with 600 mg clopidogrel and 300 mg aspirin. Major adverse cardiovascular events, comprising all-cause death, nonfatal infarction, nonfatal stroke, and ischaemia-driven target vessel revascularization, was the primary efficacy end point. TIMI major bleeding was the key safety end point.

Results:

Analyses drawn from the propensity-matched sample showed improved primary efficacy end point in the tirofiban group at 30-day (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.53–0.97) and at 1-year (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.57–0.96) follow up. Moreover, tirofiban group had a significantly lower 30-day all-cause mortality (secondary end point; OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.40–0.90), compared with patients who were not administered tirofiban. At 1 year, a trend towards a lower all-cause mortality was observed in the tirofiban group (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.53–1.04). No differences were found with respect to the TIMI major bleeding during the follow-up period.

Conclusions:

Tirofiban administered with PPCI, following 600 mg clopidogrel pretreatment, improved primary efficacy outcome at 30 days and at 1 year follow up without an increase in major bleeding.

Keywords: Efficacy outcome, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, primary PCI

Introduction

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) with stent implantation is currently considered the preferred treatment option for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).1 However, stent thrombosis remains an important cause of death after PPCI.2 Patients at higher risk for stent thrombosis following PPCI might benefit from more aggressive antiplatelet treatment. Neuman et al.3 have shown that the level of platelet glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa expression was an independent predictor of stent thrombosis. According to the European Society of Cardiology guidelines,4 the use of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPIs) is reasonable as bailout therapy in the event of angiographic evidence of large thrombus, slow or no reflow, and other thrombotic complications. In the most recent ACC/AHA guidelines, the adjunctive use of GPIs at the time of PCI can be considered on an individual basis for large thrombus burden or inadequate P2Y12 receptor antagonist loading.5

Randomized studies have resulted with conflicting results concerning the use of GPIs in the setting of acute myocardial infarction. Earlier trials showed the reduced risk of 30-day composite end point of death, recurrent myocardial infarction and urgent revascularization, improved ST-segment resolution, and reduced infarction zone during 30-day and 6-month follow up, without an increase in major bleeding.6–11 In addition, abciximab has been shown to improve microvascular flow and ventricular function.12–14 However, there has not been universal agreement about the importance of GPIs with PPCI in the era of 600 mg clopidogrel loading dose. Some authors showed a lower rate of the composite of death, recurrent MI, urgent TVR, and bleeding in the GPI arm, mainly driven by less target vessel revascularization and stent thrombosis.15,16 However, other randomized PPCI trials did not show benefit of GPI in reducing major adverse cardiac outcomes, rate of stent thrombosis, early or late death, infarction size, or pre-PCI coronary flow.17–22

We therefore sought to investigate the short- and long-term efficacy and safety of the periprocedural administration of tirofiban in a large Serbian PPCI centre.

Methods

Patient selection and management

We analysed data of 2995 consecutive patients registered in the prospective Clinical Center of Serbia STEMI Register between February 2007 and March 2012. The objective of the register was to gather complete and representative data on the management and short- and long-term outcome of patients with STEMI admitted to coronary unit after undergoing primary PCI in our centre. All patients for whom data were entered into the register have received written information of their participation in the registry and the long-term follow up, and their verbal consent for enrolment was obtained. All consecutive patients aged 18 or older, who presented with clinical and electrocardiographic signs of acute STEMI within 12 h after the onset of symptoms were included in the register. For the present analyses, we did not include patients who had contraindications for the use of GPIs (active internal bleeding, known bleeding diathesis, intracerebral mass, or aneurysm) and patients with cardiogenic shock at admission or patients with noncardiac conditions that could interfere with compliance with the protocol or require interruption of thienopyridine treatment. The study protocol was approved by a local research ethics committee. Primary PCI was performed via the femoral approach, using standard 6F or 7F guiding catheters. Before PPCI, 300 mg aspirin and 600 mg clopidogrel were administered. Unfractionated heparin was started as 100 IU/kg bolus; the 12 U/kg/h infusion followed if clinically indicated (atrial fibrillation, left ventricular thrombus or aneurysm, recent or recurrent venous thromboembolism, deferred sheath removal). Proton-pump inhibitor pantoprazol 40 mg or H2-blocker ranitidine 50 mg were given intravenously to all patients before PPCI; a peroral treatment followed in selected patients at risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage. GPI tirofiban was administered during the procedure in the catheterization laboratory at the discretion of the intervening cardiologist: the dose was based on body weight (25 µg/kg bolus followed by 18–24-h 0.15 µg/kg/min infusion), adjusted for renal impairment (half of the usual infusion dose if creatinine clearance <60 ml/min). Tirofiban was encouraged in patients with large, intraluminal residual thrombus, no (slow) reflow, threatening or acute vessel closure, complex lesions, or thrombotic complications.4,5

End points and definitions

Composite efficacy end point comprised total mortality, nonfatal infarction, nonfatal stroke, and ischaemia-driven target vessel revascularization. Nonfatal infarction was defined as the presence of: (a) recurrent ischaemic chest pain lasting more than 20 min; (b) reoccurrence of ST-segment deflection, T-wave inversion, or new pathognomonic Q waves in at least two contiguous leads; and (c) increase of cardiac troponin over the upper reference limit. Stroke was defined as a new onset of focal or global neurological deficit lasting more than 24 h. Computed tomography was used to classify stroke as ischaemic or haemorrhagic. Secondary efficacy end points included individual components of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and definite stent thrombosis. According to the Academic Research Consortium definition,23 definite stent thrombosis was defined as an angiographic or autopsy confirmation of thrombus that originates in the stent or in the segment 5 mm proximal or distal to the stent with presence of the acute coronary syndrome within a 48-h time window. Early stent thrombosis included acute and subacute stent thromboses. Acute stent thrombosis was defined as within first 24 h from intervention, subacute stent thrombosis as between 24 h and 30 days following intervention, and late stent thrombosis was defined in a time window from >30 days to 1 year after PPCI. Target vessel revascularization was defined as ischaemia-driven percutaneous revascularization of the target vessel performed for restenosis or other complication. Safety end point included bleeding events classified according to Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) criteria. Patients were followed-up at 30 days and at 1 year after enrolment. Follow-up data were obtained by scheduled telephone interviews and outpatient visits.

Statistical analysis

Based on the highest incidence of MACE within 30 days in the previous STEMI trials using a loading dose of 600 mg clopidogrel,19,21,24 the sample size of 921 patients per group provided 80% power to detect the superiority relative to the primary end point at a two-sided significance level of 0.05. Continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation or median with 25th and 75th quartiles, whereas categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage. Analysis for normality of data was performed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Baseline differences between groups were analysed using Mann–Whitney test and Student’s t-test for continuous variables, and Pearson chi-squared test for categorical variables. Data on patients who were lost to follow up were censored at the time of last contact. Time-to-first-event analyses were presented using Kaplan–Meier curves; differences between groups were compared using a two -sided log-rank test. The association of tirofiban administration with 30-day clinical outcomes was analysed using backward stepwise multivariable logistic regression, after adjustment for propensity score for being treated with tirofiban. Propensity score was calculated from the logistic regression model that included all significant clinical, laboratory, angiographic, and procedural confounding factors and significant treatment differences detected in the univariable analysis.

To account for potential bias in the selection process, the results were re-evaluated after generating two patient samples using propensity-matching analysis (propensity-matched sample). After ranking propensity score in an ascending order, a nearest neighbour 1:1 matching algorithm was used with callipers of 0.2 standard deviations of the logit of the propensity score. Each GPI and no-GPI patient was used in at most one matched pair, to allow creating a matched sample with similar distribution of baseline characteristics between observed groups. Based on the matched samples, conditional multivariable logistic regression was performed to determine the influence of periprocedural tirofiban on 30-day outcomes. The Cox proportional hazard model was used to determine the impact of tirofiban on clinical outcomes at 1 year. SPSS version 19 (IBM, Somers, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. A two-sided probability value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Tirofiban was used in 1143 (38.2%) of patients. The baseline demographic, clinical, angiographic, and procedural characteristics of patients who were treated with and without tirofiban during PPCI are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics in the whole cohort and in the propensity-matched sample.

| GPI (n=1143) | No GPI (n=1852) | p-value | PMS and GPI (n=923) | PMS and no GPI (n=923) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age (years) | 58 (51–68) | 60 (52–69) | <0.001 | 58 (51–68) | 59 (51–68) | 0.79 |

| Female | 289 (25.3) | 551 (29.7) | 0.009 | 245 (25.3) | 252 (25.3) | 0.75 |

| Body-mass index (kg/m2) | 26.6 (24.6–29.2) | 26.2 (24.2–29.0) | 0.02 | 26.5 (24.6–29.1) | 26.3 (24.3–28.9) | 0.14 |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 191 (16.7) | 388 (20.9) | 0.005 | 159 (16.7) | 170 (16.7) | 0.54 |

| Hypertension | 752 (65.8) | 1239 (66.9) | 0.58 | 623 (65.8) | 595 (65.8) | 0.10 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 703 (61.5) | 1123 (60.6) | 0.62 | 586 (61.5) | 568 (61.5) | 0.11 |

| Current smoking | 649 (56.8) | 961 (51.9) | 0.009 | 518 (56.8) | 499 (56.8) | 0.37 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 131 (11.5) | 182 (9.8) | 0.16 | 105 (11.5) | 89 (11.5) | 0.26 |

| Previous PCI | 41 (3.6) | 39 (2.1) | 0.02 | 21 (3.6) | 29 (3.6) | 0.89 |

| Previous CABG | 26 (2.2) | 25 (1.3) | 0.07 | 21 (2.2) | 12 (2.2) | 0.09 |

| Previous CVI | 46 (4.0) | 73 (3.9) | 0.92 | 36 (4.0) | 42 (4.0) | 0.49 |

| Clinical features | ||||||

| Time from symptoms to FMC (h) | 2.5 (1.5–4.0) | 2.5 (1.5–4.0) | 0.58 | 2.5 (1.5–4.0) | 2.5 (1.5–4.0) | 0.28 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 130 (115–150) | 140 (120–155) | <0.001 | 130 (120–150) | 135 (120–150) | 0.53 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 78 (68–88) | 76 (69–88) | 0.64 | 76 (68–88) | 76 (69–90) | 0.61 |

| Anterior infarction | 482 (42.2) | 729 (39.4) | 0.13 | 391 (42.2) | 364 (42.2) | 0.20 |

| Killip heart failure at admission | ||||||

| >1 | 171 (15.0) | 195 (10.5) | <0.001 | 121 (15.2) | 125 (15.2) | 0.84 |

| 2 | 160 (14.0) | 182 (9.8) | <0.001 | 110 (14.0) | 112 (14.0) | 0.88 |

| 3 | 11 (1.0) | 13 (0.7) | 0.52 | 8 (1.0) | 8 (1.0) | 1.00 |

| Laboratory analyses | ||||||

| Creatine kinase (U/l) | 2222 (1170–3896) | 1736 (906–3166) | <0.001 | 1925 (1124–3600) | 1940 (1068–3483) | 0.68 |

| Troponin I (µg/l) | 40.9 (12.3–103.4) | 27.5 (7.4–76.6) | <0.001 | 36.0 (12.3–97.0) | 33.9 (10.6–86.9) | 0.51 |

| Creatinine clearance (ml/min) | 90.1 (70.3–110.3) | 89.9 (68.5–111.2) | 0.92 | 91.3 (71.1–110.1) | 92.8 (72.3–111.2) | 0.09 |

| Creatinine clearance <60 ml/min | 170 (14.9) | 285 (15.4) | 0.50 | 131 (14.9) | 115 (14.9) | 0.44 |

| Haemoglobin at admission (g/dl) | 143 (132–153) | 141 (130–151) | 0.01 | 142 (132–152) | 142 (131–152) | 0.65 |

| Glucose at admission (mmol/l) | 7.1 (6.0–9.3) | 7.1 (5.9–9.2) | 0.53 | 7.0 (5.9–9.2) | 7.1 (5.9–9.3) | 0.75 |

| Leukocyte at admission (109/l) | 11.8 (9.7–14.4) | 11.0 (9.0–13.4) | <0.001 | 11.4 (9.5–14.0) | 11.6 (9.5–13.9) | 0.71 |

| Fibrinogen at admission (µmol/l) | 4.1 (3.4–5.1) | 4.1 (3.4–5.0) | 0.74 | 4.1 (3.4–5.1) | 4.0 (3.4–4.9) | 0.46 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 50 (40–55) | 50 (42–56) | 0.06 | 50 (42–55) | 50 (40–55) | 0.28 |

| Angiographic finding | ||||||

| 1-vessel disease | 481 (42.0) | 811 (43.8) | 0.40 | 393 (42.0) | 399 (42.0) | 0.71 |

| 2-vessel disease | 339 (29.7) | 566 (30.6) | 0.68 | 270 (29.7) | 283 (29.7) | 0.51 |

| 3-vessel disease | 323 (28.3) | 475 (25.6) | 0.14 | 260 (28.3) | 241 (28.3) | 0.20 |

| Left main disease | 77 (6.7) | 111 (6.0) | 0.44 | 51 (6.7) | 55 (6.7) | 0.69 |

| Infarction-related artery | ||||||

| Left anterior descending + diagonal | 485 (42.4) | 759 (41.0) | 0.43 | 381 (42.4) | 396 (42.4) | 0.60 |

| Left circumflex + obtuse marginal | 124 (10.8) | 264 (14.2) | 0.01 | 142 (10.8) | 117 (10.8) | 0.08 |

| Right coronary | 534 (46.7) | 819 (44.2) | 0.13 | 393 (46.7) | 406 (46.7) | 0.54 |

| Saphenous-vein graft | 7 (0.6 ) | 10 (0.5) | 0.11 | 7 (0.6 ) | 4 (0.6 ) | 0.39 |

| Preprocedural occlusion | 965 (84.4) | 1091 (58.9) | <0.001 | 755 (84.4) | 758 (84.4) | 0.90 |

| Bifurcation lesion | 40 (3.5) | 51 (2.8) | 0.27 | 34 (3.5) | 24 (3.5) | 0.23 |

| Diameter of reference vessel (mm) | 3 (3–3.5) | 3 (3–3.5) | <0.001 | 3 (3–3.5) | 3 (3–3.5) | 0.13 |

| Procedural characteristics | ||||||

| Stent implanted | 1062 (92.9) | 1742 (94.1) | 0.28 | 859 (92.9) | 859 (92.9) | 1.00 |

| Time from FMC to balloon (min) | 89 (40–148) | 90 (41–146) | 0.56 | 89 (40–148) | 89 (39–150) | 0.68 |

| Temporary pacemaker | 46 (4.0) | 23 (1.2) | <0.001 | 18 (4.0) | 18 (4.0) | 1.00 |

| Unsuccessful PCI | 30 (2.6) | 33 (1.8) | 0.15 | 21 (2.6) | 27 (2.6) | 0.46 |

| Infarction-related artery | ||||||

| Maximal length of stent (mm) | 23 (20–25) | 23 (19–24) | <0.001 | 23 (20–25) | 23 (20–25) | 0.96 |

| Maximal size of stent (mm) | 3 (3–3.5) | 3 (3–3.5) | <0.001 | 3 (3–3.5) | 3 (3–3.5) | 0.35 |

| Number of stents implanted | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–1) | <0.001 | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.95 |

| Drug-eluting stent | 74 (6.5) | 134 (7.2) | 0.46 | 54 (6.5) | 66 (6.5) | 0.26 |

| Procedural complications | ||||||

| Dissection | 28 (2.4) | 30 (1.6) | 0.13 | 20 (2.4) | 21 (2.4) | 0.88 |

| Suboptimal final TIMI flow grade | ||||||

| <3 | 97 (8.5) | 57 (3.1) | <0.001 | 56 (8.5) | 49 (8.5) | 0.48 |

| 2 | 52 (4.6) | 22 (1.2) | <0.001 | 29 (4.6) | 20 (4.6) | 0.25 |

| 1 | 13 (1.1) | 5 (0.3) | <0.001 | 7 (1.1) | 3 (1.1) | 0.23 |

| 0 | 32 (2.8) | 30 (1.6) | <0.001 | 20 (2.8) | 26 (2.8) | 0.46 |

Values are median (interquartile range) or n (%).

CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; CVI, cerebrovascular insult; FMC, first medical contact; GPI, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitor tirofiban; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PMS, propensity-matched sample; TIMI, Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction.

Patients who were treated with tirofiban were younger, more frequently smokers and males, with higher mean body mass index, creatine kinase, and leukocyte count at admission. Moreover, they presented more frequently with history of prior revascularization, clinical signs of heart failure, lower systolic blood pressure, smaller infarct-related artery reference diameter and more frequent suboptimal TIMI blood flow after the intervention. In addition, they were treated more frequently with temporary pacemaker implantation, as well as with coronary stents which were longer, smaller in diameter, and higher in number compared with the control group. Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of patients included in the propensity-matched sample. After accounting for selection bias there were no significant between-group differences.

Differences in cotreatment during and after PPCI are shown in Table 2. Patients treated with tirofiban were more frequently administered diuretics and inotropes, and less frequently beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and statins. After accounting for selection bias, there were no significant differences in life-saving medical cotreatment between propensity-matched samples.

Table 2.

Medical treatment during hospitalization in coronary care unit.

| GPI (n=1143) | No GPI (n=1852) | p-value | PMS and GPI (n=923) | PMS and no GPI (n=923) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 1141 (99.8) | 1850 (99.9) | 0.99 | 921 (99.8) | 922 (99.9) | 0.67 |

| Clopidogrel | 1126 (98.5) | 1848 (99.7) | 0.80 | 921 (99.8) | 921 (99.8) | 0.97 |

| Heparin | 209 (18.3) | 368 (19.9) | 0.54 | 171 (18.5) | 169 (18.3) | 0.89 |

| Beta-blocker | 955 (83.5) | 1628 (87.9) | 0.001 | 804 (87.1) | 797 (86.3) | 0.63 |

| Nitrates | 371 (32.5) | 550 (29.7) | 0.11 | 325 (35.2) | 254 (27.5) | 0.002 |

| ACE inhibitor | 778 (68.1) | 1422 (76.8) | <0.001 | 660 (71.5) | 672 (72.8) | 0.53 |

| Statins | 1042 (91.1) | 1753 (94.7) | <0.001 | 859 (93.1) | 862 (93.4) | 0.78 |

| Diuretics | 201 (17.6) | 268 (14.5) | 0.02 | 136 (14.7) | 149 (16.1) | 0.40 |

| Digitalis | 46 (4.0) | 61 (3.3) | 0.31 | 33 (3.6) | 34 (3.7) | 0.90 |

| Inotropes | 121 (10.6) | 65 (3.5) | <0.001 | 54 (5.9) | 58 (6.3) | 0.39 |

| Antiarrhythmics | 86 (7.5) | 84 (4.5) | 0.001 | 60 (6.5) | 49 (5.3) | 0.28 |

Values are n (%).

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; GPI, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitor tirofiban; PMS, propensity-matched sample.

Clinical outcomes

The impact of tirofiban on 30-day and 1-year clinical outcomes following PPCI is shown in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Efficacy and safety outcomes at 30-day follow up.

| GPI (n=1143) | No GPI (n=1852) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | PMS with GPI (n=923) | PMS and no GPI (n=923) | PM sample OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACE | 149 (13.0) | 167 (9.0) | 1.59 (1.24–2.09) | <0.001 | 85 (9.2) | 114 (12.3) | 0.72 (0.53–0.97) | 0.03 |

| Death | 65 (5.7) | 70 (3.8) | 1.53 (1.08–2.17) | 0.02 | 33 (3.6) | 51 (5.5) | 0.63 (0.40–0.90) | 0.04 |

| Reinfarction | 55 (4.8) | 59 (3.2) | 1.55 (1.06–2.25) | 0.02 | 39 (4.2) | 55 (5.9) | 0.68 (0.44–1.04) | 0.08 |

| Stroke | 14 (1.1) | 11 (0.6) | 2.07 (0.94–4.58) | 0.10 | 10 (1.1) | 4 (0.4) | 2.51 (0.78–8.04) | 0.12 |

| DST | 52 (4.5) | 57 (3.1) | 1.50 (1.02–2.21) | 0.04 | 32 (3.5) | 43 (4.7) | 0.74 (0.46–1.17) | 0.19 |

| ITVR | 15 (1.3) | 27 (1.5) | 0.90 (0.48–1.71) | 0.87 | 3 (0.3) | 4 (0.4) | 0.75 (0.16–3.35) | 0.73 |

| Total bleeding | 80 (7.0) | 75 (4.0) | 1.76 (1.27–2.43) | 0.001 | 50 (5.4) | 32 (3.5) | 1.59 (1.01–2.50) | 0.04 |

| Major bleeding | 13 (1.2) | 17 (0.9) | 1.24 (0.60–2.56) | 0.57 | 7 (0.7) | 7 (0.7) | 0.99 (0.34–2.85) | 0.99 |

| Minor bleeding | 32 (2.8) | 27 (1.4) | 2.01 (1.20–3.36) | 0.01 | 21 (2.3) | 13 (1.4) | 1.62 (0.81–2.27) | 0.17 |

| Minimal bleeding | 35 (3.0) | 31 (1.7) | 1.95 (1.19–3.20) | 0.008 | 22 (2.4) | 12 (1.3) | 2.13 (1.03–4.40) | 0.04 |

| Transfusion | 34 (2.9) | 31 (1.7) | 1.75 (1.05–2.92) | 0.03 | 17 (1.8) | 14 (1.5) | 1.21 (0.59–2.48) | 0.59 |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise stated.

DST, definite stent thrombosis; GPI, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitor tirofiban; ITVR, ischaemia-driven target vessel revascularization; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; PMS, propensity-matched sample.

Table 4.

Efficacy and safety end points at 1-year follow up.

| GPI (n=1103) | No GPI (n=1782) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | PMS with GPI (n=923) | PMS and no GPI (n=923) | PM sample OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACE | 220 (19.9) | 275 (15.4) | 1.55 (1.26–1.90) | <0.001 | 120 (13.0) | 155 (16.8) | 0.74 (0.57–0.96) | 0.02 |

| Death | 103 (9.3) | 127 (7.1) | 1.34 (1.02–1.76) | 0.03 | 59 (6.4) | 78 (8.4) | 0.74 (0.53–1.04) | 0.08 |

| Reinfarction | 72 (6.5) | 85 (4.8) | 1.41 (1.02–1.94) | 0.04 | 43 (4.7) | 59 (6.4) | 0.73 (0.49–1.07) | 0.11 |

| Stroke | 20 (1.8) | 24 (1.3) | 1.35 (0.74–2.46) | 0.35 | 13 (1.4) | 10 (1.1) | 1.24 (0.54–2.85) | 0.61 |

| DST | 58 (5.2) | 61 (3.5) | 1.71 (1.19–2.47) | 0.004 | 35 (3.8) | 46 (5.0) | 0.75 (0.47–1.18) | 0.21 |

| ITVR | 25 (2.3) | 39 (2.2) | 1.04 (0.62–1.73) | 0.89 | 5 (0.5) | 8 (0.9) | 0.83 (0.31–2.41) | 0.79 |

| Total bleeding | 90 (8.2) | 106 (5.9) | 1.41 (1.05–1.88) | 0.02 | 60 (6.5) | 52 (5.6) | 1.16 (0.79–1.71) | 0.44 |

| Major bleeding | 14 (1.3) | 20 (1.1) | 1.14 (0.57–2.25) | 0.72 | 8 (0.9) | 9 (1.0) | 0.88 (0.35–2.31) | 0.81 |

| Minor bleeding | 37 (3.4) | 30 (1.7) | 2.03 (1.25–3.31) | 0.005 | 25 (2.7) | 13 (1.4) | 1.94 (0.93–3.82) | 0.07 |

| Minimal bleeding | 39 (3.5) | 56 (3.1) | 1.26 (0.83–1.91) | 0.28 | 27 (2.9) | 30 (3.2) | 0.94 (0.61–1.78) | 0.88 |

| Transfusion | 36 (3.3) | 33 (1.9) | 1.79 (1.11–2.89) | 0.02 | 22 (2.4) | 16 (1.7) | 1.38 (0.73–2.71) | 0.41 |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise stated.

DST, definite stent thrombosis; GPI, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitor tirofiban; ITVR, ischaemia-driven target vessel revascularization; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; PMS, propensity-matched sample.

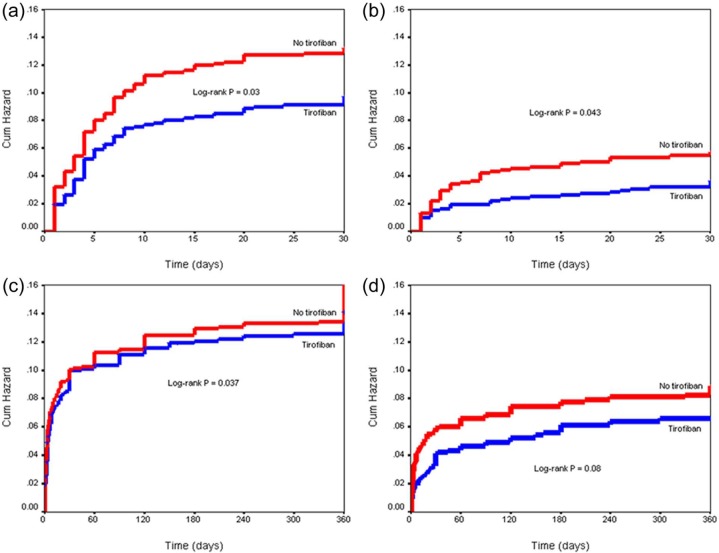

We matched 923 tirofoban patients (propensity-matched GPI group) with 923 patients who were not treated with GPI (propensity-matched control group). A significantly improved primary outcome was found in the tirofiban group compared with control at 30-day (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.53–0.97, p=0.03) and at 1-year (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.57–0.96, p=0.02) follow up. The treatment group had a significantly lower 30-day all-cause mortality compared with control (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.40–0.90, p=0.04). After 1 year, there was a trend towards lower mortality in the treatment group (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.53–1.04, p=0.08). The Kaplan–Meyer curves of cumulative hazard for MACE and all-cause mortality at 30 days and at 1 year in the propensity-matched sample are shown on Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meyer curves of cumulative hazard in the propensity-matched sample for 30-day MACE (a), 30-day all-cause mortality (b), 1-year MACE (c), and 1-year all-cause mortality (d).

MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events.

Trend towards a lower rate of nonfatal infarction was observed in the GPI group at 30-day (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.44–1.04, p=0.08) and at 1-year (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.49–1.07, p=0.11) follow up. Administration of tirofiban was associated with an increased rate of total bleeding (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.01–2.50, p=0.04) which was completely driven by an increased rate of TIMI minimal bleeding (OR 2.13, 95% CI 1.03–4.40, p=0.04) at 30-day follow up. At 1-year follow up, there was a trend towards increased rate of TIMI minor bleeding in the tirofiban group (OR 1.94, 95% CI 0.93–3.82, p=0.07). No difference was found with respect to TIMI major bleedings during the follow-up period.

After excluding patients who were treated with tirofiban within 24 h following intervention as a bailout therapy (slow or no reflow phenomenon, acute stent thrombosis; n=174) from propensity-matched sample, there was still a trend towards a lower incidence of MACE (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.51–1.09, p=0.11) and all-cause mortality (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.33–1.08, p=0.10) in the tirofiban group at 30 days. The between-group difference was not significant at 1 year follow up nether for MACE (OR 1.29, 95% CI 0.86–1.94, p=0.22) nor for all-cause mortality (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.46–1.14, p=0.16).

Discussion

The present PPCI study showed that periprocedural administration of tirofiban was associated with improved 30-day and 1-year composite efficacy outcome in patients who were pretreated with 600 mg clopidogrel. Patients treated with tirofiban had significantly reduced mortality at 30-day follow up. In addition, there was a trend towards reduced 1-year mortality in the tirofiban group. The higher rate of total bleeding in the tirofiban group was driven completely by the increased rates of minor and minimal bleedings. A high-dose tirofiban regimen was used in our trial since randomized studies with abciximab versus higher-dose tirofiban have suggested similar angiographic and clinical outcomes.25,26 Specifically, high-dose tirofiban was associated with noninferior resolution of ST-segment elevation at 90 min following PPCI compared with standard dose abciximab.24 In addition, high-dose tirofiban induced a higher aggregation inhibition compared with standard-dose abciximab.27 Furthermore, a significant association of the high-dose bolus of tirofiban and a higher rate of preprocedural TIMI-3 blood flow was observed.28,29

Our register included STEMI patients who presented within 12 h from the onset of symptoms. The mean time from symptoms to first medical contact in our cohort was 2.5 h (range 1.5–4.0 h), and the mean time from first medical contact to balloon was 89–90 min (range 40–148 min). In BRAVE-3 (Bavarian Reperfusion Alternatives Evaluation) and ASSIST (A Safety and Efficacy Study of Integrilin Facilitated PCI versus Primary PCI in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) trials, the GPI was administered 73–75 min later than the thienopyridine, often in the catheterization laboratory.19,30 BRAVE-3 investigators enrolled patients presenting within 24 h from symptom onset and suggested that abciximab might have benefited a subgroup of patients who presented within 6 h of symptom onset.19 Furthermore, we analysed data from the large PPCI register which imply that we included unselected STEMI cohort. Specifically, 12.5% of patients had heart failure at admission, 16% had renal dysfunction, 20% had diabetes, 21% were over 70 years old, 40% had anterior infarction, 37.7% had 3-vessel coronary disease, and 9% had left main disease. Overall, 72.3% of patients were not low-risk patients.

The inclusion of high-risk patients who were poorly represented or excluded from previous trials may explain the positive study results with respect to MACE and mortality. Pooled analysis and meta-analysis of trials on abciximab in acute myocardial infarction noted that the mortality benefit was shown to be proportional to the baseline risk31–33 and time after symptoms onset.15 In the On-TIME trial (prehospital initiation of tirofiban in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary angioplasty), an association between the level of residual ST-segment deviation and mortality was suggested.15 Furthermore, high-dose bolus tirofiban reduced the incidence of ischaemic and thrombotic complications during high-risk PCI.34 On the contrary, only low- to intermediate-risk patients were enrolled in the BRAVE-3 trial which was negative with respect to the primary outcome.19 The mortality benefit with tirofiban (a trend) was present in our patients at 1-year follow up. Antonucci et al.35 have demonstrated a lower rate of the composite of death and reinfarction with abciximab in acute myocardial infarction patients at 1- and 6-month follow up as compared with placebo. Similarly, the benefits in the ADMIRAL trial (Abciximab before Direct angioplasty and stenting in Myocardial Infarction Regarding Acute and Long-term follow-up) were maintained at six months follow up.7 In addition, abciximab for acute myocardial infarction resulted in improved 1-year survival and lower reinfarction rates.36 However, treatment with GPIs did not affect the composite end point at 1 year in certain trials, reflecting the lack of effect on restenosis.6,20 Moreover, multivariable analysis showed no significant independent association of abciximab with 5-year mortality or combined incidence of death, recurrent MI, and target vessel revascularization.37

Clinical benefit in the CADILLAC trial (Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications) was predominantly associated with the reduced rate of ischaemia-driven target vessel revascularization and subacute stent thrombosis.6 Tcheng et al.6 found that patients with more stents implanted, with stents >18 mm, and stent diameter >2.5 mm treated with GPI had a lower rate of adverse clinical events within 48 h post PCI, compared with patients who were not administered GPI. Indeed, postprocedural TIMI grade flow <3 correlated with poor microvascular perfusion, probably due to distal embolization. Compared with TIMI flow grade 3 subgroup, postprocedural TIMI flow <3 in high-risk patients with STEMI treated by PPCI was associated with much higher enzymic infarction size, in-hospital and 1-year mortality, and lower predischarge ejection fraction, suggesting that efforts should be made to obtain early and optimal restoration of coronary flow.38 However, in another trial, obtaining a better TIMI flow did not result either with better clinical outcomes or ejection fraction, nor did it result with lower mortality.39

An association between bleeding and increased short- and long-term mortality has been well established. Bleeding complications occurred more frequently in the abciximab group compared with control, reflecting both the intensity of anticoagulation and the long interval between angioplasty and sheath removal.8,16 However, like in our trial, the use of GPIs was not associated with serious haemorrhagic complications requiring blood transfusion or vascular repair, or major bleedings.15,35 The EPILOG study (platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade and low-dose heparin during percutaneous coronary revascularization) showed that the use of a low-dose heparin regimen, together with early sheath removal and elimination of postprocedural heparin infusion, reduces any excess bleeding risk.11 Like in our patients, the low rate of major and minor bleeding in the FINESSE study (Facilitated INtervention with Enhanced reperfusion Speed to Stop Events) was found in patients who received GPI in the catheterization laboratory.17 Of importance, platelet transfusions were rarely necessary with rapidly reversible agent such as tirofiban. In addition, in a meta-analysis of 10 trials,40 the radial approach was associated with improved survival, reduced access site bleeding, and a nonsignificant trend towards reduced major bleeding, compared with the femoral access site. Possible explanation for survival benefit might be the lower rate of bleeding-related haemodynamic compromise and less lifesaving drug discontinuation. Interestingly, the rate of major bleeding was reduced in the RIVAL trial41 and RIFLE-STEACS trial,42 when the ACUITY definition (include large access-site haematoma, which is a vascular-site complication) or BARC definition, respectively, were used but not when the TIMI bleeding definition was used.

There are data suggesting that earlier administration of GPIs before PPCI increases the chances of benefit from the drug.43–45 Sethi et al.46 showed that shorter duration of symptoms resulted in reduced events after GPI use in STEMI patients undergoing PPCI. Similarly, shorter delays from onset of chest pain to tirofiban initiation and longer duration of treatment resulted with improved ST-segment resolution and coronary patency.22 A large European registry showed that early administration of abciximab in high-risk STEMI patients resulted in lower 1-year mortality.47 Early abciximab administration improved myocardial salvage and left ventricular function recovery, probably by starting early recanalization of the infarct-related artery.48 In the On-TIME 2 trial,15 patients who presented within 75 min from symptom onset demonstrated a significant reduction in MACE with tirofiban therapy. It has been revealed that early initiation of high-dose tirofiban reduced the 30-day incidence of stent thrombosis in STEMI patients treated with PPCI and stenting.49 This might be related with the composition of thrombus in early presenters which are more susceptible for antiplatelet therapy50 or the incomplete effect of clopidogrel loading on platelet aggregration in early presenters. On the other hand, prehospital initiation of high-dose bolus tirofiban did not improve initial TIMI-2 or TIMI-3 flow of the infarct-related artery or ST-segment resolution after coronary intervention, compared with initiation of tirofiban in the catheterization laboratory.22

Study limitations

Our study has some limitations that merit careful consideration. First, data were analysed using a single-centre register. Whether such results might be generated to a broad cross-section of STEMI patients is still to be examined. Even though propensity-score matching analysis was performed to account for differences in baseline characteristics, there are probably unidentified or uncorrected factors that remain. While the study cohort is relatively large, it is underpowered to evaluate infrequent endpoints such as stent thrombosis. Second, the use of tirofiban was left at discretion of investigators, according to actual guidelines. Likewise, a substantial percentage of patients given a GPI received this as a bailout therapy, a situation known to be associated with poor outcome. Moreover, aspiration thrombectomy was used infrequently in our patients. However, the use of thrombectomy devices during STEMI remains controversial.51 Further, the rate of bleeding might be influenced by an interventional approach. We used the femoral approach in the majority of our patients. Therefore, our results should not be generalized to patients who are treated predominantly by the radial approach. Established parameters related to clinical outcomes that were predictors of stent thrombosis in some earlier reports, such as myocardial blush, maximal dilatation pressure, and the performance of postdilatation were not available in the present analysis and were not included in the multivariate analysis model. Third, the majority of our patients received bare metal stents. However, recent studies have shown no advantage of drug-eluting stents over bare-metal stents in the setting of acute myocardial infarction during the follow up of 5 years.52 The rate of stent thrombosis, however, was not different in our patents with bare-metal stents and drug-eluting stents. Finally, because of the exclusion of patients with cardiogenic shock, we cannot draw any conclusions about this very high-risk subset of patients. Due to these limitations, our results should be considered as hypothesis generating and requiring exploration in a randomized trial.

Conclusions

Our results imply that periprocedural administration of tirofiban may result with improved primary outcome after PPCI. Furthermore, it might be associated with reduced all-cause mortality without an increase in serious bleeding. Those benefits were sustained throughout the follow-up period. These findings might have important implications for improving outcomes in the large number of patients undergoing catheter-based reperfusion for STEMI. Current findings remain to be further confirmed by an adequately powered randomized trial.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the medical and technical staffs of the coronary unit and catheterization laboratory participating in the PPCI program.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. Raber L, Windecker S. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention and risk of stent thrombosis. A look beyond the HORIZON. Circulation 2011; 123: 1709–1712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stone GW, Grines CL, Cox DA, et al. ; for the Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC) Investigators Comparison of angioplasty with stenting, with or without abciximab, in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 957–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neumann FJ, Gawaz M, Ott I, et al. Prospective evaluation of hemostatic predictors of subacute stent thrombosis after coronary Palmaz-Schatz stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996; 27: 15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. The Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2569–2619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013; 127: e362–e425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tcheng JE, Kandzari DE, Grines CL, et al. ; for the CADILLAC Investigators Benefits and risks of abciximab use in primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction, the Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC) Trial. Circulation 2003; 108: 1316–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Montalescot G, Barragan P, Wittemberg O, et al. Primary stenting with abciximab in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock (the ADMIRAL trial). J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39: 43–44 [Google Scholar]

- 8. The EPIC Investigators Use of a monoclonal antibody directed against the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor in high-risk angioplasty. N Engl J Med 1994; 330: 956–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. IMPACT-II Investigators Randomized placebo-controlled trial of effect of eptifibatide on complications of percutaneous coronary intervention: IMPACT-II. Lancet 1997; 349: 1422–1428 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. RESTORE Investigators Effects of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade with tirofiban on adverse cardiac events in patients with unstable angina or acute myocardial infarction undergoing coronary angioplasty. Circulation 1997; 96: 1445–1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. EPILOG Investigators Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade and low-dose heparin during percutaneous coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med 1997; 336: 1689–1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Neumann FJ, Blasini R, Schmitt C, et al. Effect of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade on recovery of coronary flow and left ventricular function after the placement of coronary-artery stents in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1998; 98: 2695–2701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Montalescot G, Antoniucci D, Kastrati A, et al. Abciximab in primary coronary stenting of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a European meta-analysis on individual patients’ data with long-term follow-up. Eur Heart J 2007; 28: 443–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schomig A, Kastrati A, Dirschinger J, et al. Coronary stenting plus platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade compared with tissue plasminogen activator in acute myocardial infarction. Stent versus Thrombolysis for Occluded Coronary Arteries in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction (STOP-AMI) Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 385–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van’t Hof AW, Ten Berg J, Heestermans T, et al. Prehospital initiation of tirofiban in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary angioplasty (On-TIME 2): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008; 372: 537–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wijnbergen I, Helmes H, Tijssen J, et al. Comparison of drug eluting and bare-metal stents for primary percutaneous coronary intervention with or without abciximab in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. DEBATER: the Eindhoven Reperfusion Study. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv 2012; 5: 313–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ellis SG, Tendera M, de Belder MA, et al. Facilitated PCI in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 2205–2217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cho JS, Her SH, Baek JY, et al. , Korea acute myocardial infarction registry investigators Clinical benefit of low molecular weight heparin for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitor. J Korean Med Sci 2010; 25: 1601–1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mehilli J, Kastrati A, Schulz S, et al. ; for the Bavarian Reperfusion Alternatives Evaluation-3 (BRAVE-3) Study Investigators Abciximab in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention after clopidogrel loading. A randomized double-blind trial. Circulation 2009; 119: 1933–1940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kastrati A, Mehilli J, Neumann FJ, et al. Abciximab in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention after clopidogrel pretreatment: the ISAR-REACT 2 randomized trial. JAMA 2006; 295: 1531–1538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dangas GD, Caixeta A, Mehran R, et al. ; for the Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction (HORIZONS-AMI) Trial Investigators Frequency and predictors of stent thrombosis after percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2011; 123: 1745–1756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. El Khoury C, Dubien PY, Mercier C, et al. ; AGIR-2 investitgators Prehospital high dose tirofiban in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. The AGIR-2 study. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2010; 103: 285–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. ; Academic Research Consortium Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation 2007; 115: 2344–2351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Valgimigli M, Campo G, Percoco G, et al. Comparison of angioplasty with infusion of tirofiban or abciximab and with implantation of sirolimus-eluting or uncoated stents for acute myocardial infarction: the MULTISTRATEGY randomized trial. JAMA 2008; 299: 1788–1799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Danzi GB, Sesana M, Capuano C, et al. Comparison in patients having primary coronary angioplasty of abciximab versus tirofiban on recovery of left ventricular function. Am J Cardiol 2004; 94: 35–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Valgimigli M, Campo G, Arcozzi C, et al. Two-year clinical follow-up after sirolimus-eluting versus bare-metal stent implantation assisted by systematic glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitor Infusion in patients with myocardial infarction: results from the STRATEGY study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50: 138–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ernst NM, Suryapranata H, Miedema K, et al. Achieved platelet aggregation inhibition after different antiplatelet regimens during percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 44: 1187–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee DP, Herity NA, Hiatt BL, et al. ; Adjunctive platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibition with tirofiban before primary angioplasty improves angiographic outcomes: results of the Tirofiban Given in the Emergency Room before Primary Angioplasty (TIGER-PA) pilot trial. Circulation 2003; 107: 1497–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bilsel T, Akbulut T, Yesilcimen K, et al. Single high-dose bolus tirofiban with high-loading-dose clopidogrel in primary coronary angioplasty. Heart Vessels 2006; 21: 102–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Le May MR, Wells GA, Glover CA, et al. Primary percutaneous coronary angioplasty with and without eptifibatide in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a safety and efficacy study of integrilin-facilitated versus primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (ASSIST). Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2009; 2: 330–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Topol EJ, Neumann FJ, Montalescot G. A preferred reperfusion strategy for acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42: 1886–1889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Stone GW, et al. Abciximab as adjunctive therapy to reperfusion in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA 2005; 293: 1759–1765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. De Luca G, Navarese E, Marino P. Risk profile and benefits from Gp IIb-IIIa inhibitors among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty: a meta-regression analysis of randomized trials. Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 2705–2713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Valgimigli M, Percoco G, Barbieri D, et al. The additive value of tirofiban administred with high-dose bolus in the prevention of ichemic complications during high-risk coronary angioplasty (the ADVANCE trial). J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 44: 14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Antoniucci D, Rodriguez A, Hempel A, et al. A randomized trial comparing primary infarct artery stenting with or without abciximab in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42; 1879–1885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Antoniucci D, Migliorini A, Parodi G, et al. Abciximab-supported infarct artery stent implantation for acute myocardial infarction and long-term survival: a prospective, multicenter, randomized trial comparing infarct artery stenting plus abciximab with stenting alone. Circulation 2004; 109: 1704–1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ndrepepa G, Kastrati A, Neumann FJ, et al. Five-year outcome of patients with acute myocardial infarction enrolled in a randomised trial assessing the value of abciximab during coronary artery stenting. Eur Heart J 2004; 25: 1635–1640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mehta SR, Ou FS, Peterson ED, et al. ; for the American College of Cardiology–National Cardiovascular Database Registry Investigators Clinical significance of post-procedural TIMI flow in patients with cardiogenic shock undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2009; 2: 56–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Comparison of primary and facilitated percutaneous coronary interventions for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: quantitative review of randomized trials. Lancet 2006; 367: 579–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Joyal D, Bertrand OF, Rinfret S, et al. Meta-analysis of ten trials on the effectiveness of the radial versus the femoral approach in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 109: 813–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mehta SR, Jolly SS, Cairns J, et al. ; RIVAL Investigators Effects of radial versus femoral artery access in patients with acute coronary syndromes with or without ST-segment elevation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60: 2490–2499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Romagnoli E, Biondi-Zoccai G, Sciahbasi A. Radial versus femoral randomized investigation in ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: The RIFLE-STEACS (Radial Versus Femoral Randomized Investigation in ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60: 2481–2489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Huber K, Aylward PE, van’t Hof AW, et al. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors before primary percutaneous coronary intervention of ST-elevation myocardial infarction improve perfusion and outcomes: insights from APEX-AMI. Circulation 2007; 116 (suppl): II–673 [Google Scholar]

- 44. De Luca G, Gibson CM, Bellandi F, et al. Early Glycoprotein IIb-IIIa Inhibitors in Primary Angioplasty (EGYPT) cooperation: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Heart 2008; 94: 1548–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dudek D, Siudak Z, Janzon M, et al. European registry on patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction transferred for mechanical reperfusion with a special focus on early administration of abciximab: EUROTRANSFER Registry. Am Heart J 2008; 156: 1147–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sethi A, Bahekar A, Doshi H, et al. Tirofiban use with clopidogrel and aspirin decreases adverse cardiovascular events after percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Can J Cardiol 2011; 27: 548–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rakowski T, Siudak Z, Dziewierz A, et al. Early abciximab administration before transfer for primary percutaneous coronary interventions for STelevation myocardial infarction reduces 1-year mortality in patients with high-risk profile. Results from EUROTRANSFER registry. Am Heart J 2009; 158: 569–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bellandi F, Maioli M, Leoncini M, et al. Early abciximab administration in acute myocardial infarction treated with primary coronary intervention. Intern J Cardiol 2006; 108: 36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Heestermans AA, van Werkum JW, Hamm C, et al. Marked reduction of early stent thrombosis with pre-hospital initiation of high-dose tirofiban in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Thromb Haemost 2009; 10: 1612–1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Collet JP, Montalescot G, Lestly C, et al. Effects of abciximab on the architecture of platelet- rich clots in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary coronary intervention. Circulation 2001; 103: 2328–2331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sianos G, Papafaklis MI, Daemen J, et al. Angiographic stent thrombosis after routine use of drug-eluting stents in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. The importance of thrombus burden. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50: 573–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Boden H, van der Hoeven BL, Liem SS, et al. Five-year clinical follow-up from the MISSION intervention study: sirolimus-eluting stent versus bare metal stent implantation in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, a randomised controlled trial. EuroIntervention 2012; 7: 1021–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]