Abstract

Objectives. Media play an important role in the diffusion of innovations by spreading knowledge of their relative advantages. We examined media coverage of retailers abandoning tobacco sales to explore whether this innovation might be further diffused by media accounts.

Methods. We searched online media databases (Lexis Nexis, Proquest, and Access World News) for articles published from 1995 to 2011, coding retrieved items through a collaborative process. We analyzed the volume, type, provenance, prominence, and content of coverage.

Results. We found 429 local and national news items. Two retailers who were the first in their category to end tobacco sales received the most coverage and the majority of prominent coverage. News items cited positive potential impacts of the decision more often than negative potential impacts, and frequently referred to tobacco-caused disease, death, or addiction. Letters to the editor and editorials were overwhelmingly supportive.

Conclusions. The content of media coverage about retailers ending tobacco sales could facilitate broader diffusion of this policy innovation, contributing to the denormalization of tobacco and moving society closer to ending the tobacco epidemic. Media advocacy could increase and enhance such coverage.

Tobacco retailers play a key role in perpetuating the tobacco epidemic.1 Tobacco outlet density increases the likelihood of smoking among both minors and adults,2–5 and living in close proximity to tobacco outlets is associated with unsuccessful quit attempts.6,7 These observed relationships may be explained by pervasive tobacco advertising (including tobacco displays) in tobacco retail outlets, which triggers smoking among smokers and former smokers8,9 and encourages smoking initiation by youths10–17 by enhancing smoking’s apparent popularity and desirability.18,19 The ubiquity of tobacco outlets also undermines a strong public health message that tobacco products are addictive and deadly.20

Although several cities have outlawed tobacco sales at pharmacies,21,22 there are as yet few public policy mandates aimed at reducing the number of tobacco retailers. However, a number of retailers have voluntarily ended tobacco sales. Independent pharmacies were among the first,23–26 followed by some local, regional, and national grocery and discount chains.

Media attention may be an important factor influencing wider adoption of these innovative policies, as the media play an important role in the diffusion of innovations. Through the media, potential adopters gain knowledge of and a sense of familiarity with an innovation’s compatibility with organizational values, possible positive or negative consequences, and relative advantages, including its economic profitability, social prestige, cost, convenience, rewards, and time savings.27 In the process, the media may reduce perceptions of the innovation as novel or risky or enhance perceptions of its advantages, facilitating its wider adoption.28

Research has examined the characteristics that distinguish tobacco-free pharmacies from those that sell tobacco24,25,29 and why some California retailers have given up tobacco sales,30 but no studies have explored media coverage of retailer abandonment of tobacco sales. This article examines the media’s role in the dissemination of information about this voluntary policy innovation. We sought to learn if the media singled out this policy for attention and, if so, to what extent. We also explored whether the content of media coverage suggested support for wider adoption of this policy.

METHODS

We searched 3 online media databases (Lexis Nexis, Proquest, and Access World News) for news items published between 1995 and 2011 concerning US retailers who had voluntarily abandoned tobacco sales. The 3 databases covered 1441 new sources, including 995 local and national newspapers; 11 magazines; 60 newswires; 256 Web-only news sources; 26 ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox news broadcasts; and National Public Radio news broadcasts. We used a variety of search terms to locate news items, starting with general terms intended to capture all supermarkets, grocery stores, pharmacies, or other retailers who had voluntarily ended tobacco sales (e.g., [grocer* or chain or retailer or supermarket or “drug store” or pharmac*] AND [stop or end or drop or quit or eliminat* or remov* or discontinue] AND [tobacco or cigarette or smok*]). We used retrieved items to identify more specific search terms (e.g., the names of particular retailers who had stopped selling tobacco). We stopped searching once no new items were found. We included items with nearly identical content that were published in multiple news outlets to understand the reach of media coverage.

We coded news items through a collaborative, multistep process. Three coders created an initial set of codes after reviewing 8 news items. We then applied these codes to an additional 10 news items, refining, adding, and removing codes. To assess intercoder reliability, 2 coders independently coded an overlapping set of 21% (n = 91) of the items (chosen with a random number generator) in a 3-step process. First, the 2 coders independently coded 37 news items, then met with the primary and senior authors to discuss discrepancies and refine coding instructions. This process was repeated with 10 additional news items; after discussion, several codes were removed and coding instructions were further refined. Finally, each coder independently coded a final batch of 44 news items to confirm these final changes with the coding instructions. After establishing intercoder reliability with the overlapping sample31 (methodology explained in the next paragraph), each coder independently coded half of the remaining news items. We also recoded the overlapping set of 91 items to be consistent with changes to the codebook. We coded story characteristics (e.g., news source, story type, date, photo, page number, word length) and content. For the purposes of this article, we focused our analysis on content that might influence wider adoption of this voluntary policy, including retailers’ reasons for ending tobacco sales, potential impacts of doing so, responses to the decision, mention and portrayal of tobacco use and the tobacco industry, and mention of the policy as unconventional or not. We also compared the content of news items concerning 2 retailers who received the majority of coverage.

We assessed intercoder reliability using the κ statistic. Some κ values were adjusted to account for the homogeneity of the material.32 The κ statistic becomes unreliable without sufficient variety in coding; for example, if on 1 item the correct code is “no” 90% of the time, the resulting κ has a low value even when interrater agreement is high. For the overlapping sample of 91 items, all of the reported nonstatic variables achieved adjusted κ values of 0.60 or greater. Variables that did not achieve a κ value greater than 0.60 included the overall slant of the article and whether the item mentioned lost profits as a reason for opposing a voluntary end to tobacco sales. These were not used in the analysis and are not reported. Average intercoder reliability for all reported variables was 0.83, which has been characterized as “almost perfect” agreement.31,33 No additional significance testing was done because the items collected were not a random sample and we are not extrapolating from them.34 Rather, we report the findings from the entire population of items meeting the search criteria.

RESULTS

We found 429 news items published from 1995 to 2011 about retailers voluntarily ending tobacco sales. Most (367) were local or national newspaper articles, but items also included news wires, magazine articles (largely from trade magazines such as Supermarket News and Progressive Grocer), and broadcast and Web-based news (Table 1). News stories or features and letters to the editor constituted the majority of items (264 and 85, respectively); brief blurbs announcing the decision and editorials were in the minority (53 and 27, respectively). Item length ranged from 19 to 2799 words, with a median of 313 words.

TABLE 1—

News Items (n = 429) on Retailers Voluntarily Ending Tobacco Sales: United States, 1995–2011

| Variable | No. (%) |

| News source | |

| Local newspaper | 356 (83.0) |

| National newspaper | 11 (2.6) |

| Trade magazine | 21 (4.9) |

| General audience magazine | 1 (0.23) |

| News wire | 30 (7.0) |

| Television news broadcast | 1 (0.23) |

| National Public Radio broadcast | 1 (0.23) |

| Web site | 8 (1.9) |

| Geographic region | |

| West | 66 (15.4) |

| Midwest | 63 (14.7) |

| South | 61 (14.2) |

| Northeast | 166 (38.7) |

| National | 73 (17.0) |

| Story type | |

| News or feature | 264 (61.5) |

| Blurba | 53 (12.4) |

| Editorial or op-ed | 27 (6.3) |

| Letter to the editor | 85 (19.8) |

| Prominence (newspapers only; n = 367) | |

| Front page | 32 (8.7) |

| First page of section | 49 (13.3) |

| Photo | 50 (13.6) |

| Retailer type | |

| Target | 116 (27.0) |

| Wegmans | 153 (35.7) |

| Other supermarkets/grocery stores | 80 (18.6) |

| Pharmacies | 59 (13.8) |

| Other discount stores | 5 (1.1) |

| Other retailer typeb | 9 (2.1) |

| None provided | 7 (1.4) |

Brief announcement, often included in summaries of current events.

Bookstores, liquor stores, coffee shops, newsstands, etc.

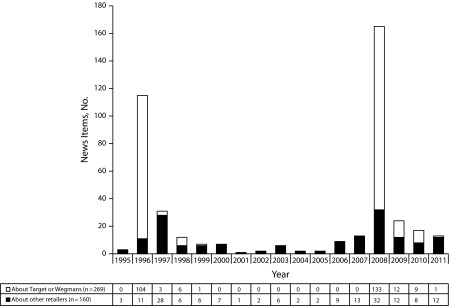

The volume of news coverage of retailers voluntarily ending tobacco sales varied between 1995 and 2011 (Figure 1). Two years accounted for the majority of coverage: 1996, when Target, a nationwide discount store and pharmacy, discontinued tobacco sales, and 2008, when Wegmans, a Northeast supermarket and pharmacy chain, did so. Both stores were the first in their category to end tobacco sales. Other retailers who ended tobacco sales at the same time as Target or Wegmans or in the year following may have benefited from the heightened attention because media coverage of all other retailers peaked during those periods (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Number of news items about retailers voluntarily ending tobacco sales, by year: United States, 1995–2011.

News items on retailers voluntarily ending tobacco sales appeared in media throughout the United States (Table 1), although the Northeast accounted for the majority, primarily reflecting coverage of Northeastern supermarket chain Wegmans. National news media (New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, USA Today, NBC nightly news, National Public Radio, magazines, news wires, and Web sites) also covered the issue, although to a lesser extent than local news. The majority (76.7%) of national news items concerned Target (9), Wegmans (30), and other supermarkets or groceries (17). National newspaper and magazine coverage did not generate any letters to the editor.

In newspapers, issues considered editorially important are likely to be given greater prominence—placed on the front page, the front page of a section, or accompanied by a photograph.35 In our study, among items published in newspapers, 32 (8.7%) appeared on the front page, 49 (13.3%) appeared on the first page of a section (other than the section containing the front page), and 50 (13.6%) had photos accompanying the articles. Target and Wegmans garnered the majority of front page newspaper articles devoted to retailers voluntarily ending tobacco sales (24 of 32 or 75.0%), and the majority of articles appearing on the first page of a newspaper section (29 of 49, or 59.2%). However, the majority of newspaper articles with photos concerned retailers other than Target or Wegmans that had abandoned tobacco sales (35 of 50, or 70%).

Reasons for Ending Sales

Retailers’ reasons for ending tobacco sales can be broadly categorized as health-related (awareness of tobacco’s health hazards, protecting children, placing people over profits, pressure from public health advocates, etc.) and business-related (e.g., declining tobacco sales, tobacco’s regulatory burden, concerns about theft of tobacco products; Table 2). In contrast to news items about other retailers, news items about Target never cited tobacco’s health hazards as a reason given by the company for ending tobacco sales. Instead, Target representatives described the change as a business decision related to avoiding the regulatory burden associated with tobacco sales (which incurred both financial costs and customer inconvenience) and no longer wanting to stock a heavily-shoplifted item. Some news items added that Target’s new policy was reportedly unrelated to moral or ethical concerns.73–76

TABLE 2—

Content of News Items (n = 429) Concerning Retailers Who Voluntarily Ended Tobacco Sales: United States, 1995–2011

| Content | Total (%) | Example |

| Retailer reasons for ending tobacco sales | ||

| Declining tobacco sales or other financial motivation | 114 (26.6) | “Discount chain cites steady decline in sales as reason for its decision to stop selling cigarettes.”36 |

| Tobacco’s health hazards | 111 (25.9) | “We have come to this decision after thinking about the role smoking plays in people’s health.”37 |

| Tobacco’s regulatory burden | 85 (19.8) | “It’s become a hassle … getting clerks to enforce tobacco regulations.”38 |

| Tobacco inconsistent with other product lines | 48 (11.2) | “We were selling $1,500 prescriptions for cancer drugs in the back of the store and cigarettes out front.”39 |

| A business decision | 48 (11.2) | “I understand that people will be happy or unhappy about the decision, but it was a business decision.”40 |

| Shoplifting of tobacco products | 45 (10.5) | “Heavy shoplifting squeezed profit margins on cigarettes.”41 |

| Personal reason | 40 (9.3) | “His brother lost two-thirds of a lung to cancer.”42 |

| Trying to protect children | 36 (8.4) | “‘We just didn’t feel good about selling [tobacco],’ Sprague said, citing the temptation posed … to the many teens who work in the store.”43 |

| Placing people over profits | 11 (2.6) | “Valesky’s does not wish to obtain profit from the sale of any item which can harm our customers or their families.”44 |

| Pressure from public health advocates | 8 (1.9) | “A growing movement nationwide for [drug stores] to discontinue tobacco sales … and the urging of local health activists were considerations in their decision.”45 |

| Denormalization of tobacco | 8 (1.9) | “Declining sales and changing consumer lifestyles were cited by ShopKo as reasons for the decision.”46 |

| Following others’ lead | 3 (0.70) | “[The owner] said that Wegmans’ decision helped influence him to discontinue selling smokes.”47 |

| Image enhancement | 3 (0.70) | “I decided to remove the … tobacco because I felt we were out of alignment with the values of the community.”48 |

| Potential impact of voluntarily ending tobacco sales | ||

| Inspire other retailers to follow suit | 115 (26.8) | “They are setting a great example for other companies to do the same.”49 |

| Lost profits | 109 (25.4) | “His business will take a serious hit, about $50,000 a year in lost sales.”42 |

| Improved health | 82 (19.1) | “By pulling tobacco from their shelves, these stores are helping to curb the devastating toll tobacco takes on our community.”50 |

| Fewer customers | 70 (16.3) | “The company feared that not selling cigarettes would cause a drop-off in customer traffic.”51 |

| Encourage children not to smoke | 52 (12.1) | “He hopes their decision not to sell cigarettes will discourage young people from smoking.”52 |

| Image improvement | 43 (10.0) | “[The decision] plays well from a social standpoint.”53 |

| Less smoking in general | 36 (8.4) | “The harder it is for people to get tobacco, the easier it is for them to end the scourge of this addiction.”51 |

| Greater profit | 20 (4.7) | “It may give them a competitive edge because some shoppers will say that’s socially responsible.”54 |

| Responses to decision | ||

| Positive customer reaction | 33 (7.7) | “I give him a lot of credit for standing up for what he believes.”52 |

| Negative customer reaction | 23 (5.4) | “They’ll lose a lot of my business.”55 |

| Neutral customer reaction | 4 (0.9) | “It makes no difference to me… . I’ll still come here anyway.”52 |

| Mixed customer reaction | 39 (9.1) | A mix of positive and negative comments. |

| Lauded by public health groups/authorities | 170 (39.6) | “The American Lung Association of New York State … commended DeCicco’s for its commitment to public health.”56 |

| Positive op-ed or letter to the editor | 88 (78.6) | “If more stores would follow Hiller’s lead, we would make incalculable strides toward eradicating a health threat.”57 |

| Negative op-ed or letter to the editor | 24 (21.4) | “I’m not happy about Wegmans deciding not to sell tobacco.”58 |

| Reasons for opposition to voluntarily ending tobacco sales | ||

| Inconveniences customers | 51 (11.9) | “Why would you create inconvenience for your customers? It’s a vice, but so are lottery tickets.”59 |

| Infringement on customer choice/rights | 46 (10.7) | “It’s a person’s right to buy any product they choose.”60 |

| Tobacco is legal product | 35 (8.2) | “Tops will continue to sell these products as long as it is legal to do so.”61 |

| Slippery slope—other products will also disappear from shelves | 9 (2.1) | “Once tobacco is off the shelves, … you will no longer be able to purchase alcohol products at Wegmans.”62 |

| Tobacco use and disease | ||

| Mention of tobacco use | 106 (24.7) | “Less than one in five adults [are] current tobacco users.”63 |

| Positive portrayal of tobacco use | 2 (0.5) | “Some people smoke incessantly for 40 or 50 years and never develop any health problems and [may] even outlive nonsmokers.”64 |

| Negative portrayal of tobacco use | 76 (17.7) | “It’s the biggest regret of my life, that I ever started.”39 |

| Neutral or mixed portrayal of tobacco use | 28 (6.6) | “We respect the right to smoke, but for us, this is … a question of health.”65 |

| Mention of tobacco and disease, death, or addiction | 184 (42.9) | “1,200 people die every day in the United States because they smoked or chewed.”66 |

| Mention of tobacco industry | 112 (26.1) | “The Tobacco Institute predicted that [other retailers] will continue to sell cigarettes.”67 |

| Positive portrayal of the tobacco industry | 5 (1.2) | “I don’t understand the university shutting the door on the industry. It’s built this state up so much.”68 |

| Negative portrayal of the tobacco industry | 38 (8.9) | “The number of smokers is higher … because of the predatory marketing practices of the tobacco industry.”69 |

| Neutral or mixed portrayal of the tobacco industry | 69 (16.1) | “Tobacco industry officials said the decision was Target’s prerogative.”70 |

| Extent/desirability of voluntarily ending tobacco sales | ||

| Other retailers have/will/should become tobacco free | 213 (49.7) | “More stores should stop selling tobacco products.”71 |

| Other retailers haven’t/won’t/shouldn’t become tobacco free | 128 (29.8) | “Few retailers appear poised to follow Target’s lead.”72 |

Note. News items were coded for multiple responses in each category; the percentages reported in each section reflect the percentage of items coded as “yes.”

Health-related reasons for ending tobacco sales played a larger role in news items about Wegmans (40% of all items mentioning health as a reason concerned Wegmans). Items frequently quoted owners Danny and Colleen Wegman as saying in a letter to employees, “We have come to this decision after thinking about the role that smoking plays in people’s health.”77,78 Wegmans stories typically did not mention any business motivation for ending tobacco sales. Pharmacies were more likely than other retailers to claim in news items that they ended sales because of tobacco’s poor fit with their other product offerings (65% of all items mentioning a poor fit concerned pharmacies). Several items quoted pharmacists as noting the incongruity of selling healing medicines at the pharmacy counter in the back of the store, and death in the form of tobacco products at the front.39,79–81

Potential Impacts and Community Responses

News items mentioned several potential impacts of the decision to end tobacco sales (Table 2). The most common were other retailers following suit (115) and lost profits (109). Overall, positive potential impacts of the decision to end tobacco sales (i.e., other retailers following suit, better health, fewer people smoking, youth smoking discouraged, an enhanced store image, greater profits) were cited more often (348) than were negative potential impacts (lost profits, fewer customers; 179).

Customer reaction was infrequently mentioned (Table 2). Positive and mixed reactions (a combination of positive, negative, or neutral) were more commonly reported in news items than solely negative or neutral reactions. Nearly 40% of news items included praise from public health organizations or authorities for retailers’ decision to eliminate tobacco sales. For example, an article about a newly tobacco-free business in a local Washington state newspaper included an expression of thanks from the president of a tobacco control organization, who noted that the move “helps make tobacco, a deadly addictive product, less easy to purchase … and sends a message that [the business] cares about its customers.”82(p1A)

Letters to the editor and opinion pieces were also overwhelmingly positive. A pair of writers encouraged others “to join us in patronizing those stores that have chosen not to sell tobacco products and to let those who do [sell them] know our feelings about the sale of tobacco.”83 A Buffalo News op-ed hoped for a trend:

In the fight against the well-documented health consequences of tobacco use, Wegmans’ move to get out of the tobacco business is a breath of fresh air and worth spreading to other retailers who have long hidden behind the excuse of “It’s a legal product.”84(pA6)

Reasons for opposing retailers’ voluntary abandonment of tobacco sales appeared infrequently (2.1%–11.9% of items; Table 2). The most commonly cited reasons for opposition centered on negative impacts for customers (inconvenience and taking away choice or “rights”).

Mention and Portrayal of Tobacco Use

Nearly a quarter of news items mentioned tobacco use (e.g., who used tobacco, the type of product used, the context in which it was used). The portrayal of tobacco use was usually negative, with items pointing out, for example, that smoking was akin to “ingest[ing] poison”85 and that “many of us know someone who wishes they didn’t smoke.”86 Nearly half of the news items mentioned a tobacco-caused disease such as cancer and heart disease, death or addiction, sometimes citing statistics such as “smoking kills more than 430,000 Americans every year”87 or “every day, 70 New Yorkers die from a tobacco-related disease.”66 Items published in the business section of newspapers were less likely to mention tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease, death, or addiction than were those published in other newspaper sections. The tobacco industry (in general or a particular tobacco company) was mentioned in about one quarter of news items (usually regarding Target’s decision to end tobacco sales), and was rarely portrayed positively (Table 2).

Uniqueness of the Policy

News items were more likely to suggest that retailers’ voluntary policy represented a current or future trend rather than that such policies were an aberration: nearly 50% mentioned other retailers who had also ended tobacco sales voluntarily, or might or should do so in the future, versus 30% that mentioned other retailers who had not stopped selling tobacco or would not or should not do so (Table 2).

A Closer Look at Target- and Wegmans-Related Items

To gain a greater understanding of patterns and characteristics of media coverage of this issue, we explored in more detail items concerning the 2 retailers who received the bulk of coverage, Target and Wegmans. We found that although Target-related items were more prominent in terms of front page and first-page of section placement and photos accompanying stories, the Target-related news cycle was relatively short: the majority of coverage occurred over a 9-day period, compared with a 9-month period for the majority of Wegmans-related items. Wegmans’ news cycle was extended by numerous editorials, opinion pieces, and letters to the editor, including 12 letters written by regional or local tobacco control advocates or health professionals. In addition to responding to initial news stories in local newspapers, letter writers responded to opinion pieces, other letter writers, and additional news about Wegmans’ product offerings. By contrast, Target’s 9-day news cycle included only 1 letter (written by a Florida tobacco control organization).

A closer look at the content of letters responding to initial newspaper articles about Wegmans’ decision to end tobacco sales (16 articles published in local newspapers between January 5 and 7, 2008) revealed that supporters (25 of 35 letter writers) primarily wrote to voice their approval. They offered “congratulations,” “kudos,” “bravo,” or “hats off” to Wegmans and cited the potential (general) health benefits or mentioned tobacco-caused death and disease. Only 1 mentioned that reduced access to tobacco products might reduce smoking prevalence. We were unable to identify particular themes in Wegmans-related news items that may have sparked reader responses. However, an examination of the initial newspaper articles found differences among those that did (7) and did not (9) inspire letters. Those that generated letters had a higher median word count (519 vs 132), appeared more often on the front page (4/7 vs 1/9) and less often in the business section (0/7 vs 3/9), and more often had accompanying photos (2/7 vs 0/9).

DISCUSSION

This study has limitations. The news databases we searched are not comprehensive, although they cover a wide range of national and local newspapers. Our search terms, although comprehensive, may not have been exhaustive; thus, we may not have identified and included relevant news items in our study. We also chose to include nearly identical content published by different sources to capture the breadth of coverage; as a result, any similar content was coded multiple times. Our results, therefore, reflect all coverage that appeared, not unique stories.

Retailers’ decisions to voluntarily end tobacco sales attracted media attention. Large national and regional retailers who were the first in their category to end tobacco sales received the most media coverage. They also garnered the majority of the limited number of front page and front section page newspaper articles and national media devoted to the topic. Other retailers, including independent pharmacies and grocery stores, received less coverage and were featured less prominently in newspapers. Although tobacco-free retailers received ongoing attention during a 17-year period, the amount of coverage was relatively low. This may indicate that few retailers have ended tobacco sales; given the media’s preference for novel stories,88 future adopters of this policy innovation may continue to attract media attention. This could increase awareness and, ultimately, diffusion of the policy as more retailers become tobacco-free. The relatively low level of coverage might also indicate that there is a lack of media awareness of or interest in such retailers. If so, media advocacy efforts are needed to raise awareness of or increase the perceived newsworthiness of the topic to facilitate wider diffusion of the voluntary policy.

Despite the rather low level of media coverage, the content of coverage reflected overall support for this voluntary policy innovation. For example, media coverage suggested that the policy was compatible with traditional retailer values centered on profit and loss as well as with consumer-safety values. News items cited declining tobacco sales or tobacco’s regulatory burden as retailers’ reasons for ending sales. However, they also noted that retailers were motivated by awareness of tobacco’s health hazards, and ambivalence regarding or reluctance to sell products that harmed customers. The fact that news items frequently contained praise from public health authorities for the decision reinforced the sense that consumer protection was an appropriate retailer concern. Consumer safety values in relation to the decision to end tobacco sales were also evident in the negative portrayal of tobacco use and the frequent mentions (nearly half of all items) of tobacco and disease, death, or addiction.

The content of media coverage also suggested that this voluntary policy offered most of the relative advantages associated with the adoption of innovations.27(p216) These included no initial cost, immediate savings in time and effort through fewer regulations with which to comply, (potentially) enhanced social prestige, and elimination of the discomfort caused by selling deadly products. News coverage offered limited support for the idea that ending tobacco sales enhanced or did not decrease profitability, a key component of the diffusion of innovations. Nonetheless, coverage suggested that the potential consequences of the policy were more likely to be positive than negative. Positive impacts of the decision to end tobacco sales were mentioned more frequently than negative impacts, opposition was mentioned infrequently, and editors’ and readers’ responses were overwhelmingly supportive.

In spreading knowledge of this policy innovation—including its compatibility with multiple organizational values, its relative advantages, and its potential for positive consequences—media coverage suggested that abandoning tobacco sales was not a particularly risky move by retailers. Moreover, because half of news items referred to other retailers who had also gone tobacco-free, might do so, or should do so in the future, media coverage suggested that tobacco-free retailers could become the norm. Thus, to date, media coverage about retailers ending tobacco sales appears likely to facilitate rather than inhibit the diffusion of this policy innovation.

Our study suggests that there are opportunities for media advocacy around this issue beyond raising awareness. The potential for retailers’ decision to positively impact public health by reducing youth smoking or reducing smoking more generally was rarely mentioned, despite research showing that reduced tobacco retailer density is associated with reduced smoking uptake and increased cessation.2–4,6,7 The tobacco industry was also mentioned surprisingly infrequently. Its absence from news items about retailers voluntarily ending tobacco sales obscures its role in promoting tobacco sales through contracts that provide rewards to retailers for preferential product displays and point-of-sale advertising.89 Advocates might consider using media advocacy to promote particular messages about this aspect of the tobacco business or about the potential positive public health impacts of retailers voluntarily ending tobacco sales.

Our closer look at patterns of media coverage of the retailers that received the most attention, Target and Wegmans, offers insight into how positioning of initial news stories may promote further discussion, extending coverage (and presumably awareness) of the issue. Placement of new stories in sections other than the business section (particularly the front page), longer pieces, and accompanying photos appear to be associated with additional coverage. Tobacco control advocates can play a role in extending coverage by writing letters and op-eds, as many did in Wegmans’ case, both about initial stories and in response to any negative opinion pieces or letters.90 Coordinating letter writing among various groups, particularly when national chains end tobacco sales, could leverage more coverage. The Target decision represented a missed opportunity to show support for the decision and to educate the public and retailers about the public health benefits of ending tobacco sales.

Innovative decisions made by individual retailers to end tobacco sales, and the media coverage these generate, both reflect and shape social understandings about tobacco. In this way, they contribute to altering the public perception that selling deadly products is normal and acceptable, just as policy mandates like retail tobacco product display bans do. Each small step that brings to the foreground of media attention questions about the normalcy of tobacco sales and use moves society a step closer to ending the tobacco epidemic.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grant 1R01 CA143076).

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was not needed because no human research participants were involved.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Ending the Tobacco Problem: A Blueprint for the Nation. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novak SP, Reardon SF, Raudenbush SW, Buka SL. Retail tobacco outlet density and youth cigarette smoking: a propensity-modeling approach. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):670–676. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.061622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henriksen L, Feighery EC, Schleicher NC, Cowling DW, Kline RS, Fortmann SP. Is adolescent smoking related to the density and proximity of tobacco outlets and retail cigarette advertising near schools? Prev Med. 2008;47(2):210–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipperman-Kreda S, Grube JW, Friend KB. Local tobacco policy and tobacco outlet density: associations with youth smoking. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(6):547–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams ML, Jason LA, Pokorny S, Hunt Y. Exploration of the link between tobacco retailers in school neighborhoods and student smoking. J Sch Health. 2013;83(2):112–118. doi: 10.1111/josh.12006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reitzel LR, Cromley EK, Li Y et al. The effect of tobacco outlet density and proximity on smoking cessation. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(2):315–320. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.191676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halonen JI, Kivimaki M, Kouvonen A et al. Proximity to a tobacco store and smoking cessation: a cohort study. Tob Control. 2013 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050726. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wakefield M, Germain D, Henriksen L. The effect of retail cigarette pack displays on impulse purchase. Addiction. 2008;103(2):322–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burton S, Clark L, Jackson K. The association between seeing retail displays of tobacco and tobacco smoking and purchase: findings from a diary-style survey. Addiction. 2012;107(1):169–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Feighery EC, Fortmann SP. A longitudinal study of exposure to retail cigarette advertising and smoking initiation. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):232–238. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henriksen L, Flora JA, Feighery EC, Fortmann SP. Effects on youth of exposure to retail tobacco advertising. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2002;32(9):1771–1789. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henriksen L, Feighery EC, Wang Y, Fortmann SP. Association of retail tobacco marketing with adolescent smoking. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2081–2083. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lovato CY, Hsu HC, Sabiston CM, Hadd V, Nykiforuk CI. Tobacco point-of-purchase marketing in school neighbourhoods and school smoking prevalence: a descriptive study. Can J Public Health. 2007;98(4):265–270. doi: 10.1007/BF03405400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slater SJ, Chaloupka FJ, Wakefield M, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM. The impact of retail cigarette marketing practices on youth smoking uptake. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(5):440–445. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.5.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spanopoulos D, Britton J, McNeill A, Ratschen E, Szatkowski L. Tobacco display and brand communication at the point of sale: implications for adolescent smoking behaviour. Tob Control. 2014;23(1):64–69. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackintosh AM, Moodie C, Hastings G. The association between point-of-sale displays and youth smoking susceptibility. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(5):616–620. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paynter J, Edwards R, Schluter PJ, McDuff I. Point of sale tobacco displays and smoking among 14–15 year olds in New Zealand: a cross-sectional study. Tob Control. 2009;18(4):268–274. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.027482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dewhirst T. POP goes the power wall? Taking aim at tobacco promotional strategies utilised at retail. Tob Control. 2004;13(3):209–210. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollay RW. More than meets the eye: on the importance of retail cigarette merchandising. Tob Control. 2007;16(4):270–274. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.018978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapman S, Freeman B. Regulating the tobacco retail environment: beyond reducing sales to minors. Tob Control. 2009;18(6):496–501. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights. Tobacco-Free Pharmacies. Available at: http://www.no-smoke.org/learnmore.php?id=615. Accessed April 22, 2013.

- 22.Kroon LA, Corelli RL, Roth AP, Hudmon KS. Public perceptions of the ban on tobacco sales in San Francisco pharmacies. Tob Control. 2013;22(6):369–371. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hickey LM, Farris KB, Peterson NA, Aquilino ML. Predicting tobacco sales in community pharmacies using population demographics and pharmacy type. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2006;46(3):385–390. doi: 10.1331/154434506777069507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bentley JP, Banahan BF, McCaffrey DJ, Garner DD, Smith MC. Sale of tobacco products in pharmacies: results and implications of an empirical study. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1998;38(6):703–709. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)30391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotecki JE, Hillery DL. A survey of pharmacists’ opinions and practices related to the sale of cigarettes in pharmacies-revisited. J Community Health. 2002;27(5):321–333. doi: 10.1023/a:1019884526205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eule B, Sullivan MK, Schroeder SA, Hudmon KS. Merchandising of cigarettes in San Francisco pharmacies: 27 years later. Tob Control. 2004;13(4):429–432. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.007872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wejnert B. Integrating models of diffusion of innovations: a conceptual framework. Annu Rev Sociol. 2002;28:297–326. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotecki JE, Fowler JB, German TC, Stephenson SL, Warnick T. Kentucky pharmacists’ opinions and practices related to the sale of cigarettes and alcohol in pharmacies. J Community Health. 2000;25(4):343–355. doi: 10.1023/a:1005168528085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDaniel PA, Malone RE. Why California retailers stop selling tobacco products, and what their customers and employees think about it when they do: case studies. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:848. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical variables. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lantz CA, Nebenzahl E. Behavior and interpretation of the k statistic: resolution of the two paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(4):431–434. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00571-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munoz SR, Bangdiwala SI. Interpretation of kappa and B statistics measures of agreement. J Appl Stat. 1997;24(1):105–112. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glantz SA. Primer of Biostatistics. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Medical; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Booth A. The recall of news items. Public Opin Q. 1970;34(4):604–610. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levin M. ShopKo banishing tobacco products; retail: discount chain cites steady decline in sales as reason for its decision to stop selling cigarettes and related items in its department stores. Los Angeles Times. November 5, 1997:3. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wegmans grocery chain to stop selling tobacco. Associated Press. January 4, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Contrada F. Retailer gives up tobacco license. Springfield Union News. January 22, 1997:B1. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ager S. Drugstore crushes out tobacco sales. St. Louis Post-Dispatch. January 10, 1996:IE. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kahn A. Target discount chain to stop selling cigarettes. It cites business, not health reasons: high theft rate, low profit margin, costs of checking age of customers. Akron Beacon Journal. August 29, 1996:E2. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Target stores is getting out of the cigarette business. The Bismarck Tribune. August 29, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brewster deli stops selling cigarettes. The Danbury News-Times. February 28, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drake K. More grocers go smoke-free as they shun tobacco sales. Salt Lake Tribune. June 14, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meadville supermarket ends tobacco sales. Erie Times-News. February 19, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woodford R. Drug store says “no more” to tobacco sales–the store joins others locally and nationally going cold turkey off tobacco products. Juneau Empire. January 21, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 46.ShopKo stores end sale of tobacco products. PR Newswire. November 3, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Another small NY grocer drops cigarettes. Progressive Grocer. February 19, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Girl’s appeal leads to alcohol ban at dad’s store. Associated Press. September 21, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gillet S. Local chain stops selling tobacco. The Davis County Clipper. May 27, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marino A, McGee P. Stores that ban sales of tobacco deserve support. Albany Times Union. February 25, 2008:A6. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glatter S. End scourge of cigarette addiction. The Bergen County Record. January 30, 2007:L06. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saxton B. Deli snuffs out cigarettes. The Danbury News-Times. March 2, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pressler MW. Cigarette foes forecast a battle in stores; Target cites profit dip in move to end sales. Washington Post. August 29, 1996:B13. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soper S. Wegmans quits tobacco sales habit; Supermarket chain with Valley stores puts health before profits. Allentown Morning Call. January 5, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Associated Press. Target stores won’t sell cigarettes. Dubuque Telegraph Herald. August 29, 1996:B5. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Small gourmet NY. grocer to drop tobacco. Progressive Grocer. February 11, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kilpatrick KE. Stores should ban smokes. The Detroit News. January 27, 2009:12A. [Google Scholar]

- 58.McKeen M. Smoker unhappy with Wegmans. Erie Times-News. January 19, 2008:2. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marckini J. Wegmans kicks the habit. Wilkes-Barre Times Leader. January 13, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Doyle JR. Idea to ban supermarket sales of tobacco gets mixed reviews. Utica Observer-Dispatch. January 13, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rivers T. Tops pressed on tobacco products. The Batavia Daily News. June 11, 2010:3A. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Richmond J. Next, Wegmans will ban alcohol, dairy and cleaning products, etc. Syracuse Post-Standard. January 9, 2008:A9. [Google Scholar]

- 63.St. Onge NJ. Unlike high fat or sugar products, no level of tobacco use is healthy. Syracuse Post-Standard. January 9, 2008:A9. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stucchio C. Risks posed by diet cannot be overlooked. Buffalo News. January 30, 2008:A7. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Karpeuk A. Grocery store says ‘no’ to tobacco use. University Wire. January 15, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meyers K. Why do pharmacies still sell cigarettes? Syracuse Post-Standard. April 27, 2009:A13. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kahn A. Target stores to stop selling cigarettes. Saint Paul Pioneer Press. August 28, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ferreri E. No sale: UNC’s shops stop selling smokes–Prof’s efforts help weed out cigarette sales on campus. Chapel Hill Herald. April 4, 2004:1. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Buckham T. Smith wants to limit tobacco sale outlets. Buffalo News. November 21, 2009:D2. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Target stores will end sales of cigarettes. Seattle Post-Intelligencer. August 29, 1996:B6. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meyers K. More stores should stop selling tobacco products. Utica Observer-Dispatch. May 20, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Taget quits cigs. New York Daily News. August 29, 1996:89. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Store ends all sales of cigarettes–Target decision may have sweeping effect. Watertown Daily TImes. August 28, 1996:6. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zarroli J. Target will dump tobacco products from shelves. All Things Considered, National Public Radio. August 29, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 75.714-store chain; a business, not moral decision; Target targets cigarettes, pulls them off its shelves. Wilmington Star-News. August 29, 1996:5C. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Target chain to halt sale of cigarettes. Buffalo News. August 28, 1996:B7. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Grocery chain to stop tobacco sales. The Hanover Evening Sun. January 7, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pall of smoke over Harrisburg. Scranton Times-Tribune. January 7, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brown P. Durham drugstore will stop selling cigarettes. Raleigh News and Observer. May 11, 1995:B1. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thompson E. Small pharmacies drop tobacco lines; 3 area independents felt conflict. Worcester Telegram & Gazette. May 21, 1996:A1. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nuckols C. Pharmacist’s a maverick in his field; no alcohol, no tobacco. The Roanoke Times. April, 3, 1997:C1. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Porter M. Cruisin Coffee dropping cigarettes. The Bellingham Herald. July 22, 2000:1A. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Seelman A, Seelman J. Patronize stores that don’t sell tobacco products. Utica Observer-Dispatch. July 8, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hirshberg S. Other merchants should follow Wegmans’ lead. Buffalo News. January 24, 2008:A6. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Erb G. Deadly smoking. Harrisburg Patriot-News. January 22, 2008:A11. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schwennesen T. Smoking issue gets yes and no at University of Oregon. The Eugene Register Guard. January 14, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 87.Blair L. State should prohibit cigarettes in pharmacies. Buffalo News. May 25, 2009:A7. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gans H. Deciding What’s News. New York, NY: Pantheon; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lavack AM, Toth G. Tobacco point-of-purchase promotion: examining tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2006;15(5):377–384. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dorfman L. Using media advocacy to influence policy. In: Bensley RJ, Fisher J, editors. Community Health Education Methods: A Practitioner’s Guide. Boston, MA: Jones & Bartlett; 2003. pp. 383–409. [Google Scholar]