Significance

Heme oxygenase (HO) is a key enzyme for heme degradation that is deeply involved in iron homeostasis, defensive reaction against oxidative stress, and signal transduction mediated by carbon monoxide. To complete a single HO reaction, seven electrons supplied from NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) are required. Based on crystallography, X-ray scattering, and NMR analyses of CPR, it has been proposed that CPR has a dynamic equilibrium of the “closed-open transition.” The crystal structure of the transient complex of CPR with heme-bound HO clearly demonstrated that it is the open form of CPR that can interact with and transfer electrons to heme-bound HO. Moreover, the complex structure provides a scaffold to research the protein–protein interactions between CPR and other redox partners.

Abstract

NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (CPR) supplies electrons to various heme proteins including heme oxygenase (HO), which is a key enzyme for heme degradation. Electrons from NADPH flow first to flavin adenine dinucleotide, then to flavin mononucleotide (FMN), and finally to heme in the redox partner. For electron transfer from CPR to its redox partner, the ‘‘closed-open transition’’ of CPR is indispensable. Here, we demonstrate that a hinge-shortened CPR variant, which favors an open conformation, makes a stable complex with heme–HO-1 and can support the HO reaction, although its efficiency is extremely limited. Furthermore, we determined the crystal structure of the CPR variant in complex with heme–HO-1 at 4.3-Å resolution. The crystal structure of a complex of CPR and its redox partner was previously unidentified. The distance between heme and FMN in this complex (6 Å) implies direct electron transfer from FMN to heme.

Electron transfer is a fundamental process in all living organisms. Marvelous electron relay systems lie in the mitochondrial respiratory chain and in the photosystem in chloroplasts. For other redox enzymes, there are also small-scale but beautiful electron transfer systems constituted from hemes, flavins, iron–sulfur clusters, or various metals. NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (CPR, EC 1.6.2.4) is a member of a family of diflavin reductases including methionine synthase reductase (EC 1.16.1.8), the reductase domains of nitric oxide synthase and cytochrome P450 BM3 (EC 1.14.13.39 and EC 1.14.14.1), and the flavoprotein subunit of sulfite reductase (EC 1.8.1.2), each of which catalyzes electron transfer through the pathway from NADPH to flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), then to flavin mononucleotide (FMN), and finally to heme groups in their redox partners (1, 2). The diflavin reductase family has evolved by fusion of two ancestral genes: one is related to an FMN-containing flavodoxin and the other to an FAD-containing ferredoxin–NADP+ oxidoreductase (FNR). In rat CPR, residues 77–228 originated from flavodoxin and residues 267–325 and 450–678 originated from FNR. The amino acid residues of the connecting domain between the flavodoxin-like and FNR-like domains were interspersed in the FNR-like domain (residues 244–266 and 326–450). The connecting domain and the FNR-like domain together formed the FAD domain wherein the NADPH-binding site also resides. The flavodoxin-like domain evolved into the FMN domain. The FAD and FMN domains are connected by a flexible hinge with a span of 12 amino acid residues, Gly232 to Arg243 in rat CPR. CPR is a membrane-bound protein anchored to the cytoplasmic surface of the endoplasmic reticulum with N-terminal 55 residues of CPR.

For electron transfer to take place, CPR and its redox partners must associate with each other. A previously reported CPR structure shows a closed conformation in which NADP+, FAD, and FMN are close to each other; therefore, this conformation is suitable for intramolecular electron transfer (3). However, it is hardly conceivable that the redox partners such as cytochrome P450 could approach closely enough to FMN for intermolecular electron transfer to occur. Site-directed mutagenesis analysis demonstrated that the acidic clusters (Asp207-Asp208-Asp209 and Glu213-Glu214-Asp215 in rat CPR) near FMN are involved in the association with cytochrome P450s (4), but these clusters were covered by the FAD domain in the closed conformation (3). Therefore, a large conformational change in CPR is expected to take place for smooth interaction between CPR and its redox partners and for swift progression of enzymatic reactions.

Recently, Hamdane et al. produced a rat CPR mutant, hereafter referred to as ΔTGEE, in which four consecutive amino acid residues in the hinge region (residues from Thr236 to Glu239) were deleted and found that ΔTGEE crystallized in three remarkably extended conformations (open conformation, PDB ID code: 3ES9); the distance between FAD and FMN cofactors ranged from 30 to 60 Å (5). The structures of ΔTGEE indicate that the FMN domain is highly mobile with respect to the rest of the molecule, whereby the open conformation of CPR is able to bind cytochrome P450. The molecular size of the least-extended conformation of ΔTGEE was comparable to that of the closed conformation, whereas the orientation of the FMN domain was remarkably different from that in the closed conformation. As a result, FMN was exposed to the surface in the least-extended conformation of ΔTGEE, which is suitable to transfer electrons to the redox partner. They have proposed that CPR undergoes a large conformational rearrangement in the course of shuttling electrons from NADPH to cytochrome P450. Chimeric CPR from yeast and humans also exhibits the open conformation (6). Small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and NMR analyses of wild-type CPR indicate that the equilibrium between the closed and open conformations depends on the redox state of CPR and the binding of NADPH (7, 8). However, no crystal structure of the complex of CPR and its redox partner has been determined.

Heme oxygenase (HO, EC 1.14.99.3), which catalyzes the degradation of heme to biliverdin, carbon monoxide (CO), and ferrous ion (9–11), is one of the physiological redox partners of CPR. The HO reaction proceeds via a multistep mechanism. The first step is the oxidation of heme to α-hydroxyheme, requiring O2 and reducing equivalents supplied by CPR. The second step is the formation of verdoheme with the concomitant release of hydroxylated α-meso carbon as CO. The third step is the conversion of α-verdoheme to a biliverdin–iron chelate, for which O2 and electrons from CPR are also required. In the final step, the iron of the biliverdin–iron chelate is reduced by CPR, and, finally, ferrous ion and biliverdin are released from HO. Biliverdin is subsequently converted to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase. The major physiological role of HO in mammals, which is assigned to an inducible isoform, HO-1, is the recycling of iron, detoxification of heme, a pro-oxidant, and production of bilirubin, a potent anti-oxidant. CO produced by HO-1 and a constitutive isoform, HO-2, mediates various types of cell signaling, such as anti-inflammation, anti-apoptosis, and vasodilatation (12, 13).

Rat HO-1 (rHO-1) used in this study is a recombinant protein whose membrane anchor region (C-terminal 22 residues) has been truncated. The complex of rHO-1 with heme (heme–rHO-1) is a single polypeptide consisting of eight α-helices, A–H, in which the first 9 and the last 43 residues are disordered in the crystal (14). The heme is sandwiched between a proximal A-helix (Leu13-Glu29) and a distal F-helix (Leu129-Met155); the side chain of His25 in the A-helix contributes as the proximal ligand and Gly139 and Gly143 in the F-helix are close to the distal ligand of the heme iron. The heme is also fixed through electrostatic interactions between its propionate groups and the basic residues (Lys179 and Arg183).

To complete a cycle of the HO reaction, HO consumes seven electrons provided by CPR whereas cytochrome P450s consume only two electrons. Therefore, it is fully conceivable that a ‘‘closed-open transition’’ of CPR must operate during the HO reaction. In this study, we report characterization of the HO reaction with ΔTGEE and describe the crystal structure of the ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 complex. This is a previously unidentified crystal structure of the complex of CPR with one of its redox partners and will contribute to understanding the complicated HO reaction. Furthermore, the complex structure should provide an excellent structural basis to discuss interaction of CPR with other redox partners.

Results

Single Turnover HO Reaction Mediated by ΔTGEE.

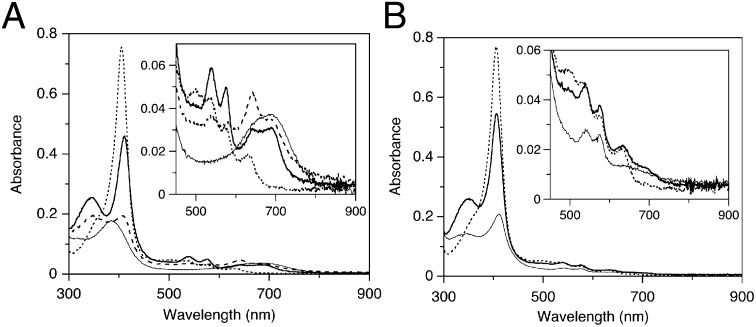

Hamdane et al. demonstrated that the rate of the interflavin electron transfer from FAD to FMN in ΔTGEE was decreased by two to three orders of magnitude compared with wild-type CPR and that the ability of ΔTGEE to support catalysis by cytochrome P450 was undetectable (5). However, when the FMN in ΔTGEE was fully reduced in advance, ΔTGEE supported product formation by cytochrome P450 under single turnover conditions at the same rate as the wild-type CPR-supported reaction. Thus, ΔTGEE is capable of transferring electrons from FMN to heme in cytochrome P450. As stated above, the HO reaction is a fairly complex reaction requiring seven electrons from CPR. Thus, it is interesting to examine how the CPR variant ΔTGEE behaves in the HO system. First, we examined the single-turnover HO reaction mediated by the NADPH-ΔTGEE system. With the wild-type CPR (0.04 μM), the oxy-form was formed immediately and then CO–verdoheme and verdoheme forms appeared. Within 20 min, heme was fully converted to biliverdin (Fig. 1A). However, in the case of ΔTGEE (0.4 μM), the oxy-form was observed 30 min after addition of NADPH, and then biliverdin–iron chelate was finally formed after 120 min (Fig. 1B); the generation of biliverdin–iron chelate was confirmed by its conversion to biliverdin after the addition of the iron chelator, desferrioxiamine (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Absorption spectral changes of heme–rHO-1 during the single-turnover reaction supported with a NADPH–wild-type CPR or NADPH–ΔTGEE system. (A) Reaction with 0.04 μM wild-type CPR. The spectra were recorded before (dotted line) and 1 min (heavy line), 5 min (dashed line), and 20 min (solid line) after the addition of NADPH. (B) Reaction with 0.4 μM ΔTGEE. The spectra were recorded before (dotted line) and 30 min (heavy line) and 120 min (solid line) after the addition of NADPH. Insets show the magnified view in the visible region.

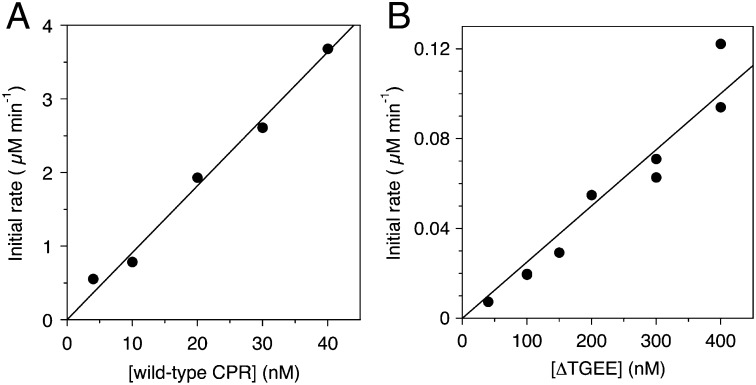

The reduction rate of ferric heme iron in heme–rHO-1 was measured by the formation rate of CO-bound heme–rHO-1 in a CO-saturated atmosphere. From the slope fitted with a least square method, the rate constants for the heme reduction of heme–rHO-1 were determined to be 90.9 min−1 for wild-type CPR and 0.250 min−1 for ΔTGEE. The reduction rate mediated by ΔTGEE was 360-fold slower than that mediated by wild-type CPR (Fig. 2). Thus, ΔTGEE proved to be capable of reducing the ferric heme iron in heme–rHO-1, although its efficacy is extremely limited. We previously reported that FMN-depleted CPR could not mediate the reduction of ferric heme iron in heme–rHO-1 (15). Therefore, it should be reasonable to consider that only reduced FMN, not reduced FAD, in wild-type CPR as well as in ΔTGEE can reduce the ferric heme iron. This conclusion is consistent with the structure of the ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 complex reported in this paper.

Fig. 2.

Reduction rate of heme in heme–rHO-1 by NADPH–wild-type CPR or NADPH–ΔTGEE system. Absorption spectral changes of 5 µM of heme–rHO-1 with wild-type CPR (A) or ΔTGEE (B) after the addition of NADPH (25 µM) were recorded at 25 °C under CO-saturated conditions. The initial rates of reduction of ferric heme in complex with rHO-1 were determined from the absorbance changes at 406 and 420 nm as described in Methods.

Heme–rHO-1 Forms a Stable Complex with ΔTGEE.

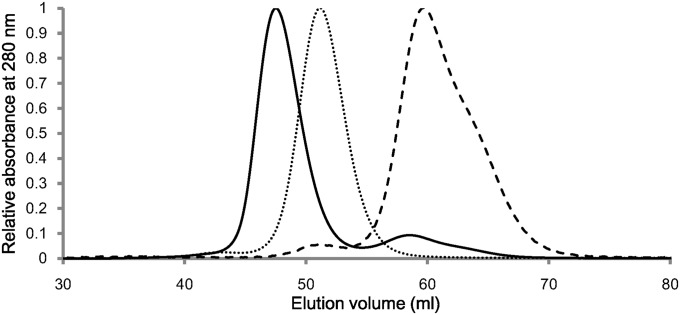

For electron transfer to take place, there must be some interaction (transient or somewhat stable complex formation) between rHO-1 and ΔTGEE. To probe the nature of this interaction, we first investigated the behavior of the two enzymes by size-exclusion chromatography. As shown in Fig. 3, when ΔTGEE and heme–rHO-1 were separately applied to chromatography, ΔTGEE and heme–rHO-1 complex were eluted at 51.2 and 59.5 mL, corresponding to the elution volumes of monomeric ΔTGEE and heme–rHO-1, respectively. When the mixture of ΔTGEE and heme–rHO-1 was applied, two peaks at an elution volume of 47.5 and 58.6 mL were observed (Fig. 3); UV-visible absorption spectroscopy and SDS/PAGE revealed that the former peak was due to the ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 complex (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B). The complex peak was never observed when the mixture of ΔTGEE and heme-free apo rHO-1 was applied; thus, ΔTGEE does not form a stable complex with apo rHO-1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). That ΔTGEE binds only to heme–rHO-1 means that ΔTGEE recognizes the subtle conformational changes of rHO-1 upon heme binding. Upon rechromatography, the coeluted ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 complex was again eluted as a single peak, indicating that the ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 complex is very stable. It should be noted that wild-type CPR does not coelute with heme–rHO-1 under similar conditions, indicating that ΔTGEE associates much more stably with heme–rHO-1 than wild-type CPR does.

Fig. 3.

Size-exclusion chromatography. The elution profiles of ΔTGEE plus heme–rHO-1(solid line), heme–rHO-1(dashed line), and ΔTGEE (dotted line) from HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-200 HR column.

More quantitative analysis was done by surface plasmon resonance (SPR). SPR analysis showed that the dissociation constant (Kd) of the heme–rHO-1 complex for ΔTGEE was 0.1–0.2 μM, which is 10- to 20-fold smaller than that for wild-type CPR (16). SPR analysis also showed that apo rHO-1 did not interact with ΔTGEE. These results are consistent with those obtained from the size-exclusion chromatography. Furthermore, we previously reported that the R185A mutation in rHO-1 weakened the interaction between heme–rHO-1 and wild-type CPR (Kd = 44 μM) (16). This mutation also weakened the interaction with ΔTGEE (Kd = 8.9 μM).

Crystal Structure of the ΔTGEE–Heme–rHO-1 Complex.

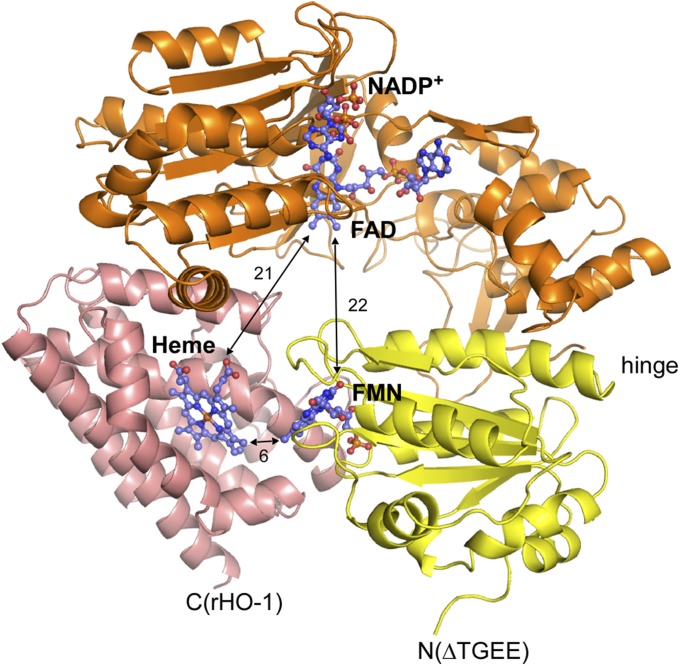

As the ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 complex was stable, this complex could be crystallized and the crystal structure of the complex was determined at 4.3-Å resolution as described in Methods; it should be noted that thus far we have never succeeded in cocrystallization of the wild-type CPR with heme–rHO-1 under similar conditions (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Table S1). Two independent ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 complexes were in the asymmetric unit. Each complex contained one molecule each of NADP+, FAD, FMN, and heme. Because NADP+ was not present during crystallization, it must bind to ΔTGEE during purification as NADP+ was used for the elution from the 2′, 5′-ADP Sepharose affinity column (GE Healthcare) (17). The electron density of the FMN domain is weaker than that of the FAD domain and rHO-1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), suggesting that the mobility of the FMN domain is high relative to the remaining portion. In addition, the crystal structure was roughly consistent with SAXS data from the ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 complex in solution (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), indicating that the binding manner of ΔTGEE and heme–rHO-1 in crystal was not largely affected by crystal packing. Three independent crystal structures of ΔTGEE were reported by Hamdane et al. (5). One of them, the least-extended conformation (referred to as “Mol A” in their paper) (5) , was almost identical to ΔTGEE in the ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 complex (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The rmsd of Cα atoms with Mol A of ΔTGEE is 1.3 Å. In contrast to the closed conformation of CPR, the distance between FAD and FMN in the complex is 22 Å; electron transfer between FAD and FMN in this complex is apparently difficult. Heme bound to rHO-1 is close to FMN, and the distance between FMN and heme is 6 Å, indicating that the direct electron transfer from FMN to heme is possible (Fig. 4) (18). The C7–C8 edge of the isoalloxazine ring of FMN is directed toward the A-ring of heme. Both of the edges of FMN and heme are exposed to the surface.

Fig. 4.

Crystal structure of the ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 complex. Ribbon diagram of FMN (yellow) and FAD (orange) domains of ΔTGEE and rHO-1 (pink) were shown with the stick models of the cofactors and heme. Distances between heme and FMN, heme and FAD, and FMN and FAD are shown in angstrom units. The N-terminal side of ΔTGEE and the C-terminal side of heme–rHO-1 face in the same direction. This figure was prepared with PyMOL (34).

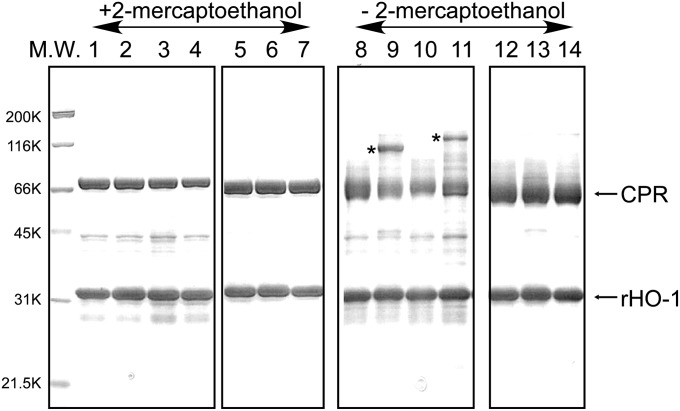

Total interface area between heme–rHO-1 and ΔTGEE is 989.9 Å2; the polar surface area is 348.8 Å2, and the nonpolar surface area is 641.1 Å2. Heme–rHO-1 interacts with ΔTGEE through two separated parts: one is in the FMN domain, and the other is in the FAD domain. This is direct evidence that the FAD domain is also involved in the interaction with its redox partner. To confirm the regions involved in the direct interaction between rHO-1 and wild-type CPR, we prepared pairs of mutated rHO-1 and CPR into which one cysteine residue was introduced to each protein. Based on the structure of the ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 complex, we predicted the possible positions where a disulfide bond between CPR and rHO-1 could be formed; these positions were Val146 of rHO-1 and Thr88 of CPR and Lys177 of rHO-1 and Gln517 of CPR (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Thr88 and Gln517 of CPR are in the FMN and FAD domains, respectively. The formation of disulfide bonds between two proteins was investigated by SDS/PAGE analyses with or without reducing agents and Western blot (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S7). As predicted, the bands corresponding to the CPR–rHO-1 complex appeared in SDS/PAGE carried out without reducing agents (Fig. 5). These bands did not appear in SDS/PAGE carried out with reducing agents, indicating the presence of the intermolecular disulfide bond. Western blots using anti-HO or anti-CPR antibodies demonstrated that these bands contain both HO and CPR (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Also, these bands did not appear when the counterpart protein was a wild type, implying that the cysteine residues introduced are involved in the formation of the disulfide bond. These results indicate that the wild-type CPR associates with heme–rHO-1 in a similar manner as that in the structure of the ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 complex.

Fig. 5.

SDS/PAGE analysis of artificial disulfide bond formation between CPR and heme–rHO-1. Expression and purification of cysteine-introduced wild-type CPR and rHO-1 as well as the detailed experimental procedures are described in Methods. Gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Samples in lanes 1–7 were applied with 2-mercaptoethanol and those in lanes 8–14 were applied without 2-mercaptoethanol. M.W., molecular weight marker; lanes 1 and 8, heme–His6–rHO-1 plus T88C His6–CPR; lanes 2 and 9, V146C heme–His6–rHO-1 plus T88C His6–CPR; lanes 3 and 10, heme–His6–rHO-1 plus Q517C His6–CPR; lanes 4 and 11, K177C heme–His6–rHO-1 plus Q517C His6–CPR; lanes 5 and 12, heme–His6–rHO-1 plus wild-type CPR; lanes 6 and 13, V146C heme–His6–rHO-1 plus wild-type CPR; lanes 7 and 14, K177C heme–His6–rHO-1 plus wild-type CPR. Bands with an asterisk indicate formation of the intermolecular disulfide bond between CPR and heme–rHO-1.

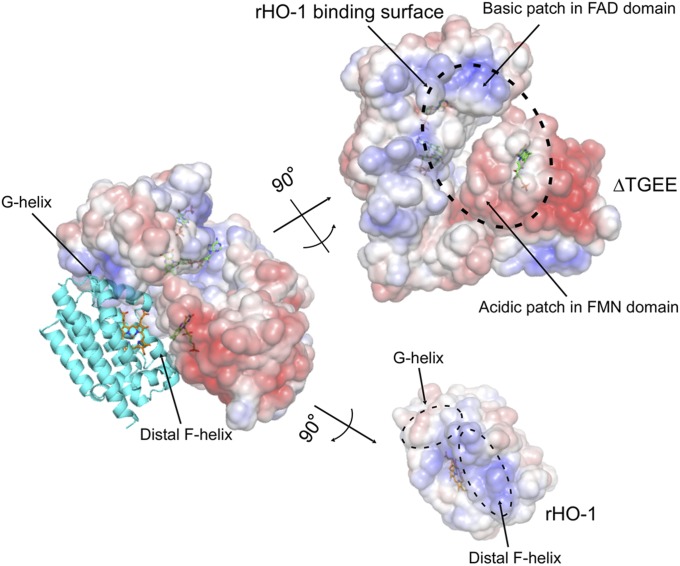

Fig. 6 shows the electrostatic potential on the surfaces of heme–rHO-1 and ΔTGEE. An acidic patch in the FMN domain and a basic patch in the FAD domain are involved in the interaction. The interface of heme–rHO-1 in contact with ΔTGEE is almost basic, especially the C-terminal part of the distal F-helix; this segment seems to be important for binding to FMN domain. The surface corresponding to the G-helix in heme–rHO-1 is somewhat acidic; this part seems to be crucial for binding to the FAD domain. These electrostatic interactions between heme–rHO-1 and ΔTGEE seem to be critical to fix the orientation of each molecule. Previously, Salinas et al. showed that the S188D mutation of human HO-1, which mimics the phosphorylation by AkT/PKB, slightly strengthened the interaction with CPR (19). Ser188 of human HO-1 corresponds to Thr188 of rHO-1, which is in the G-helix and close to Lys523 in the FAD domain in the complex structure. Thus, this substitution or phosphorylation by AkT/PKB acidified the G-helix of HO-1 and strengthened the interaction with the basic FAD domain of CPR.

Fig. 6.

Electrostatic potential of the interface between ΔTGEE and heme–rHO-1. Positive and negative surfaces are shown in blue and red, respectively (±5.0 kT/e). The potential was calculated with APBS software (35). This figure was prepared with PyMOL (34).

For crystallization in this study, we used soluble forms of CPR and HO-1; i.e., the membrane anchor of each molecule was truncated. Full-length rat CPR and rat HO-1 have membrane anchor regions at the N terminus and at the C terminus, respectively. Notably, in the ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 structure, the N-terminal residue of ΔTGEE (Val64) and the C-terminal residue of heme–rHO-1 (Glu223) face the same direction (Fig. 4), indicating that both proteins associate with each other, as observed in our complex structure, and face toward the microsomal membrane in vivo. To obtain further information about the interaction, such as the interactions between side chains, higher-resolution structural data will be required.

Discussion

Here we determined the crystal structure of the ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 complex, in which FMN is close to heme, but FAD and NADP+ are separated from FMN (Fig. 4). Therefore, this structure is suitable for electron transfer from FMN to heme, but not for electron transfer from FAD to FMN. This is consistent with the fact that ΔTGEE is capable of reducing heme–rHO-1, although the efficiency of the electron transfer between them is remarkably low (Figs. 1 and 2). Although ΔTGEE is a mutated CPR, experiments with Cys-introduced CPR (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S7) showed that wild-type CPR associates with heme–rHO-1 in a similar manner as ΔTGEE in ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1.

Previously, we found that Lys149, Lys153, and Arg185 of rHO-1 are critical for the interaction with CPR (16, 20). All of these residues on the surface are interacting with ΔTGEE; the FMN domain interacts with the surface that is close to Lys149 and Lys153 of rHO-1 and the FAD domain interacts with the surface that is close to Arg185 of rHO-1. Lys149 and Lys153 of rHO-1 are in the distal F-helix, and Arg185 of rHO-1 is in the G-helix. Thus, our current structure is consistent with the previous biochemical findings. We further demonstrated that NADP+ binding to CPR strengthens the interaction between heme–rHO-1 and CPR (16), although NADP+ is not directly involved in the interaction between heme–rHO-1 and ΔTGEE in the present structure. Huang et al. showed, based on SAXS experiments, that NADPH/NADP+ binding to CPR affects the equilibrium between open and closed conformations; binding of NADPH/NADP+ shrank the molecular size of CPR (7, 8). It is difficult to distinguish the closed conformation from a least-extended conformation like Mol A by SAXS because the molecular sizes of these two conformations are similar. At any rate NADPH/NADP+ binding to CPR favors the closed or the least-extended conformation of CPR as observed in ΔTGEE in the complex structure. Notably, heme–rHO-1 is tightly bound to the least-extended conformation of CPR; Kd for ΔTGEE is 10- to 20-fold smaller than that for wild-type CPR. Taking the SAXS results together with our results that NADP+ binding to CPR strengthens the association between CPR and heme–rHO-1, we conclude that NADPH/NADP+ binding to CPR leads to a shift of the equilibrium to the least-extended conformation to bind heme–rHO-1.

Apo rHO-1 does not associate with CPR (16). This is favorable from the metabolic point of view because it does not interfere with binding of CPR to the redox partners, including heme–HO. Although the overall folding of apo rHO-1 remains similar to that seen in heme–rHO-1, it interacts with neither CPR nor ΔTGEE, indicating that CPR (and also ΔTGEE) recognizes the subtle structural differences between apo rHO-1 and heme–rHO-1. The proximal A-helix in the crystal structure of apo rHO-1 is disordered (21). This is the largest difference between the structures of apo rHO-1 and heme–rHO-1, but the A-helix does not participate in association with ΔTGEE. Thus, this difference is not involved in the discrimination between apo rHO-1 and heme–rHO-1 by CPR. The distal F-helix and the B-helix also change their conformations upon heme binding (21). The distal F-helix, wherein Lys149 and Lys153 reside, clearly takes part in the interaction with FMN domain of ΔTGEE (Fig. 6). Thus, CPR recognizes the subtle conformational change of the distal helix to discriminate between apo rHO-1 and heme–rHO-1. The region surrounding Arg185 in the G-helix, which is involved in the interaction with the FAD domain, may also be involved in the discrimination between apo rHO-1 and heme–rHO-1.

Hamdane et al. have proposed that the open conformation of CPR binds and transfers electrons to cytochrome P450 and that, after the electron transfer, cytochrome P450 is displaced by the large domain motion of CPR (5). This is consistent with the recent SAXS results showing that the domain motion is linked to the redox state of CPR; the oxidized form is compact, whereas the reduced form favors the extended conformation (8). Hamdane et al. have also proposed a docking model of the complex of CPR and cytochrome P450 (5). The cytochrome P450 binding surface in CPR estimated from the docking simulation is similar to the heme–rHO-1 binding surface in ΔTGEE. Moreover, the binding surface is also consistent with the structure of FMN and heme domains of cytochrome P450 BM3, which is a natural fusion protein of cytochrome P450 and CPR (22): superimposition of ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 and cytochrome P450 BM3 (SI Appendix, Fig. S8) showed that both the heme–rHO-1 and the heme domain of cytochrome P450 BM3 interact with the FMN domain of CPR. Thus, our result suggests that their scheme concerning cytochrome P450 can also be applied to the mechanism of electron transfer to HO. NADPH reduces the oxidized CPR, and then NADP+-bound reduced CPR changes its conformation from the closed to the least-extended form to accept the heme–HO complex. After two electrons are transferred to the heme–HO complex, reoxidized CPR changes its conformation from the least extended to the closed one. Because the FMN domain is anchored to the membrane in vivo, HO would dissociate from CPR by the motion of FAD domain. Because NADP+ tightly binds to CPR (Kd = 53 nM) (23), NADP+ could be bound to CPR until another NADPH comes, implying that the closed conformation would be maintained until CPR is again reduced. Because one cycle of the HO reaction consumes seven electrons, several electron transfer cycles coupled with the conformation change of CPR have to take place between HO and CPR. In this study, we were able to provide a structural basis for further understanding of the interactions and the electron transfer mechanism between CPR and its redox partners, including HO.

Methods

Materials and Preparations of Enzymes.

Oligonucleotides were obtained from FASMAC. Hemin was a product of Sigma. Anti-CPR and anti–HO-1 antibodies were purchased from Operon and Promega, respectively.

For expression of a recombinant rat liver CPR lacking the N-terminal 57 hydrophobic amino acids, termed “wild-type CPR” in this study, and of a recombinant rat HO-1 lacking the 22-amino-acid C-terminal hydrophobic segment (rHO-1), we changed the pBAce-based vector used in our previous work (17, 24) to a pET-based vector (Merck) for the convenience of expression. The ORF region of the pBAce-based expression vectors were excised and subcloned into the NdeI-SalI site of pET-21a(+), generating the CPR/pET-21a and the rHO-1/pET-21a vectors. The enzymes expressed from these vectors contained no additional tags and were used throughout the present work except for the experiment shown in Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S7. The expression plasmid for ΔTGEE was prepared from CPR/pET-21a by the deletion of nucleotides corresponding to Thr236 to Glu239 with the KOD–Plus–mutagenesis kit (Toyobo) and of oligonucleotides, ΔTGEE-f and ΔTGEE-r (SI Appendix, Table S2). Sequence of the ORF region of the resulting plasmid was verified. CPR, rHO-1, and ΔTGEE were all expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) (Merck) at 30 °C using LB media with isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) induction and purified as reported previously (17, 24).

The heme–rHO-1 complex was reconstituted with 1.2 eq of heme and purified by column chromatography on hydroxyapatite (Bio-Rad) as previously described (25).

Single-Turnover HO Reaction of Heme–rHO-1 Supported by CPR or ΔTGEE.

Single-turnover reactions were all monitored by absorption spectral changes at 25 °C using a Varian Cary 50 Bio UV-visible spectrophotometer. The reaction mixtures (0.1 mL) consisted of 5 µM heme–rHO-1, 0.04 µM wild-type CPR, or 0.4 µM ΔTGEE and 25 µM NADPH in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Spectra were recorded over the range of 300–900 nm.

Reduction Rate of Ferric Heme–rHO-1 Mediated by Wild-Type CPR or ΔTGEE.

The heme reduction was monitored by absorption spectral changes at 25 °C using a Varian Cary 50 Bio UV-visible spectrophotometer in an anaerobic and CO-saturated atmosphere. The CO-saturated reaction mixtures (0.1 mL) consisted of 5 µM heme–rHO-1, 4–40 nM wild-type CPR or 40–400 nM ΔTGEE, and 25 µM NADPH in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The reaction was started by addition of NADPH. The initial rates of reduction of ferric heme in complex with rHO-1 were calculated from the decrease of the absorbance at 406 nm and the increase of the absorbance at 420 nm. The differences in molar absorption coefficients (Δε) between ferric heme–rHO-1 and CO-bound ferrous heme–rHO-1 used were 82.2 mM−1⋅cm−1 at 406 nm and 131 mM−1⋅cm−1 at 420 nm, respectively. Means of the initial rate obtained were plotted against the concentration of CPR. From the slope of the fitted line, rate constants for the heme reduction of heme–rHO-1 were determined.

Size-Exclusion Chromatography of ΔTGEE–Heme–rHO-1 Complex and SPR Analysis.

Purified ΔTGEE and heme–rHO-1 were mixed at a molar ratio of 1:2 at 4 °C and incubated for 1 h. Then, the mixture was applied to a HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-200 HR column connected to Äkta prime plus (GE Healthcare); the column had been equilibrated with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.7) and was eluted with the same buffer. Absorbance at 280 nm was recorded. ΔTGEE and heme–rHO-1 were also separately analyzed under the same conditions. For preparation of the crystallization sample of ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1, 20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4) was used as the equilibration and elution buffer.

The parameters of binding affinity of heme–rHO-1 to wild-type CPR or ΔTGEE were determined by SPR technology using a BIAcore 1000 instrument (BIAcore AB), as described previously (16). NADP+ was not added in this study.

Crystallization and Structure Determination of ΔTGEE–Heme–rHO-1 Complex.

The ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 complex, prepared as described above, was concentrated up to 40 mg/mL by ultrafiltration. Crystallization conditions were screened at 20 °C by sitting-drop vapor diffusion using JB Classic screening kit (Jena Bioscience). Plate-shaped orange crystals of the ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 complex were obtained at 20 °C when reservoir solution containing 20% (wt/vol) PEG 4000, 0.2 M sodium acetate, and 0.1 M Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.5) was used. Finally, reservoir conditions were optimized to 18% (wt/vol) PEG 6000, 0.2 M sodium acetate, and 0.1 M Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.6). Crystals were soaked in the crystallization solution adding PEG 6000 up to 20% (wt/vol) and 15% (vol/vol) ethylene glycol to prevent freezing and then cooled with liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at 100 K using synchrotron radiation at the beamline BL44XU, SPring-8 (Sayo, proposal nos. 2012B6758 and 2013A6863). Wavelength of X-ray is 0.9 Å for structure refinement and 1.5 Å for the anomalous difference Fourier map (SI Appendix, Fig. S3D). Diffraction data were processed, merged, and scaled with HKL2000 (26). Crystallographic statistics are summarized in SI Appendix, Table S1.

The phases of ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1 were determined by molecular replacement with Molrep (27, 28). The molecular replacement was done in three steps with each different search model. In the first step, the protein moiety of the FAD domain of CPR was used for a search model, as a result of which two FAD domains in an asymmetric unit were found. After the positions of the two FAD domains were fixed, the protein moiety of heme–rHO-1 was used for a search model in the second step, as a result of which two rHO-1 molecules in an asymmetric unit were found. Finally, the protein moiety of the FMN domain of CPR was used for a search model in the third step. In contrast to the other steps, only one FMN domain was found in the third step whereas another FMN domain was found during the refinement stage as shown below. Thus, two ΔTGEE and heme–rHO-1 molecules were found in the asymmetric unit by molecular replacement, but one FMN domain in ΔTGEE was missing.

After the rigid body refinements, the densities of two FAD molecules, two ADP parts of NADP+ molecules, two heme molecules, and one FMN molecule were found in the residual density map. Anomalous difference peaks of two heme irons were also found in the anomalous difference Fourier maps (SI Appendix, Fig. S3D). Therefore, these cofactors and substrates were added to the model of ΔTGEE–heme–rHO-1. In addition to the densities of these cofactors and substrates, the partial density of the missing FMN domain was found in the residual density map. When the model of ΔTGEE that contained FAD and FMN domains was superimposed onto the FAD domain of the other ΔTGEE in which the FMN domain was missing, the FMN domain of the ΔTGEE model fit the residual density. Therefore, the second FMN domain was added to the model. Finally, two ΔTGEE molecules, which contain FAD and FMN domains and cofactors, and two heme–rHO-1 molecules were included in the model. This model was further refined with REFMAC5 and adjusted with Coot (28–30). During the refinements, noncrystallographic symmetry restraints between two ΔTGEE molecules and those between two heme–rHO-1 molecules, jelly-body restraints, and the restraints for the secondary structures were applied because the diffraction data were limited by 4.3 Å (31, 32). The isotropic temperature factors of the individual atoms were not refined during the initial steps of refinements, but these were refined in the last step. Stereochemical checks of the models were performed with the program PROCHECK (28, 33). Two of 1,626 residues were out of the allowed area in the Ramachadran plot. Other residues (85.8% in core, 13.6% in allowed, 0.5% in generously allowed areas) were in the allowed area. Diffraction and refinement statistics are summarized in SI Appendix, Table S1. The coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the PDB code 3WKT.

Introduction of Cysteine Residues to Wild-Type CPR and rHO-1.

To simplify the purification steps of the Cys-introduced mutated enzymes, pET-15b vector was used; with this vector, enzymes are expressed with N-terminal His6 tag. The ORF regions of CPR/pET-21a and rHO-1/pET-21a were excised and subcloned into the NdeI-XhoI site of pET-15b, resulting in CPR/pET-15b and rHO-1/pET-15b. Site-directed mutagenesis for introduction of cysteine residues was done using CPR/pET-15b and rHO-1/pET-15b as the templates with the aid of KOD–Plus–mutagenesis kit and oligonucleotides T88C-CPR-f, T88C-CPR-r, Q517C-CPR-f, Q517C-CPR-r, V146C-HO-f, V146C-HO-r, K177C-HO-f, and K177C-HO-r (SI Appendix, Table S2). Sequences of the ORF regions of the resulting plasmids were verified. His6-tagged CPR and rHO-1 were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) at 30 °C using LB media with IPTG induction, and purified as reported previously (17, 24). Harvested cells were lysed with BugBuster (Merck). Supernatants after centrifugation were purified with His-accept agarose (Nacalai-Tesque) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Imidazole contained in the elution buffer was removed by several steps of ultrafiltration.

Partially purified enzymes were mixed with 12.5 μM hemin and 0.5 mM NADP+ and applied to SDS/PAGE with or without 2-mercaptoethanol. After electrophoresis, gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue or blotted onto Hybond-P membranes (GE Healthcare). Blotted membranes were blocked with 5% (wt/vol) skim milk and 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween-20 containing PBS and then reacted with anti-HO or anti-CPR rabbit IgG antibodies. Bound antibodies were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody and peroxidase-stain DAB kit (Nacalai-Tesque).

Solution Scattering Data Collection and Analysis.

SAXS measurements were carried out using the BL11 at the SAGA Light source (Tosu, proposal no. 1306069F). Details for SAXS measurements are provided in SI Appendix, SI Text S1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank beamline staffs of BL44XU at SPring-8 and BL11 at SAGA Light Source for the data collections. This work was partly supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grants 20770092 (to M.S.), 25840026 (to M.S.), 21590321 (to M.N.), 24590366 (to M.N.), and 24750169 (to J.H.) and by grants from the Ishibashi Foundation for the Promotion of Science (to M.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. T.C.P. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code: 3WKT).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1322034111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Pandey AV, Flück CE. NADPH P450 oxidoreductase: Structure, function, and pathology of diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;138(2):229–254. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iyanagi T, Xia C, Kim JJ. NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase: Prototypic member of the diflavin reductase family. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;528(1):72–89. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang M, et al. Three-dimensional structure of NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase: Prototype for FMN- and FAD-containing enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(16):8411–8416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen AL, Kasper CB. Role of acidic residues in the interaction of NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase with cytochrome P450 and cytochrome c. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(46):27475–27480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamdane D, et al. Structure and function of an NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase in an open conformation capable of reducing cytochrome P450. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(17):11374–11384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807868200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aigrain L, Pompon D, Moréra S, Truan G. Structure of the open conformation of a functional chimeric NADPH cytochrome P450 reductase. EMBO Rep. 2009;10(7):742–747. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis J, et al. Domain motion in cytochrome P450 reductase: Conformational equilibria revealed by NMR and small-angle X-ray scattering. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(52):36628–36637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.054304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang WC, Ellis J, Moody PC, Raven EL, Roberts GC. Redox-linked domain movements in the catalytic cycle of cytochrome p450 reductase. Structure. 2013;21(9):1581–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kikuchi G, Yoshida T, Noguchi M. Heme oxygenase and heme degradation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338(1):558–567. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ortiz de Montellano PR, Wilks A. In: Advances in Inorgranic Chemistry. Sykes AG, editor. Vol 51. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 359–407. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tenhunen R, Marver HS, Schmid R. The enzymatic conversion of heme to bilirubin by microsomal heme oxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;61(2):748–755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.61.2.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryter SW, Alam J, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide: From basic science to therapeutic applications. Physiol Rev. 2006;86(2):583–650. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morikawa T, et al. Hypoxic regulation of the cerebral microcirculation is mediated by a carbon monoxide-sensitive hydrogen sulfide pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(4):1293–1298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119658109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugishima M, et al. Crystal structure of rat heme oxygenase-1 in complex with heme. FEBS Lett. 2000;471(1):61–66. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higashimoto Y, et al. The reactions of heme- and verdoheme-heme oxygenase-1 complexes with FMN-depleted NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. Electrons required for verdoheme oxidation can be transferred through a pathway not involving FMN. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(42):31659–31667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606163200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higashimoto Y, et al. Involvement of NADPH in the interaction between heme oxygenase-1 and cytochrome P450 reductase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(1):729–737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406203200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayashi S, Omata Y, Sakamoto H, Hara T, Noguchi M. Purification and characterization of a soluble form of rat liver NADPH-cytochrome P-450 reductase highly expressed in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2003;29(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(03)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moser CC, Keske JM, Warncke K, Farid RS, Dutton PL. Nature of biological electron transfer. Nature. 1992;355(6363):796–802. doi: 10.1038/355796a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salinas M, et al. Protein kinase Akt/PKB phosphorylates heme oxygenase-1 in vitro and in vivo. FEBS Lett. 2004;578(1–2):90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higashimoto Y, et al. Mass spectrometric identification of lysine residues of heme oxygenase-1 that are involved in its interaction with NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;367(4):852–858. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugishima M, et al. Crystal structure of rat apo-heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1): Mechanism of heme binding in HO-1 inferred from structural comparison of the apo and heme complex forms. Biochemistry. 2002;41(23):7293–7300. doi: 10.1021/bi025662a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sevrioukova IF, Li H, Zhang H, Peterson JA, Poulos TL. Structure of a cytochrome P450-redox partner electron-transfer complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(5):1863–1868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grunau A, Paine MJ, Ladbury JE, Gutierrez A. Global effects of the energetics of coenzyme binding: NADPH controls the protein interaction properties of human cytochrome P450 reductase. Biochemistry. 2006;45(5):1421–1434. doi: 10.1021/bi052115r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Omata Y, Asada S, Sakamoto H, Fukuyama K, Noguchi M. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction studies on the water soluble form of rat heme oxygenase-1 in complex with heme. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54(Pt 5):1017–1019. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida T, Takahashi S, Kikuchi G. Partial purification and reconstitution of the heme oxygenase system from pig spleen microsomes. J Biochem. 1974;75(5):1187–1191. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a130494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: An automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Cryst. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50(Pt 5):760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53(Pt 3):240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicholls RA, Long F, Murshudov GN. Low-resolution refinement tools in REFMAC5. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2012;68(Pt 4):404–417. doi: 10.1107/S090744491105606X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murshudov GN, et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schrodinger LLC. 2010. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3r1. Available at www.pymol.org. Accessed January 27, 2014.

- 35.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: Application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(18):10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.