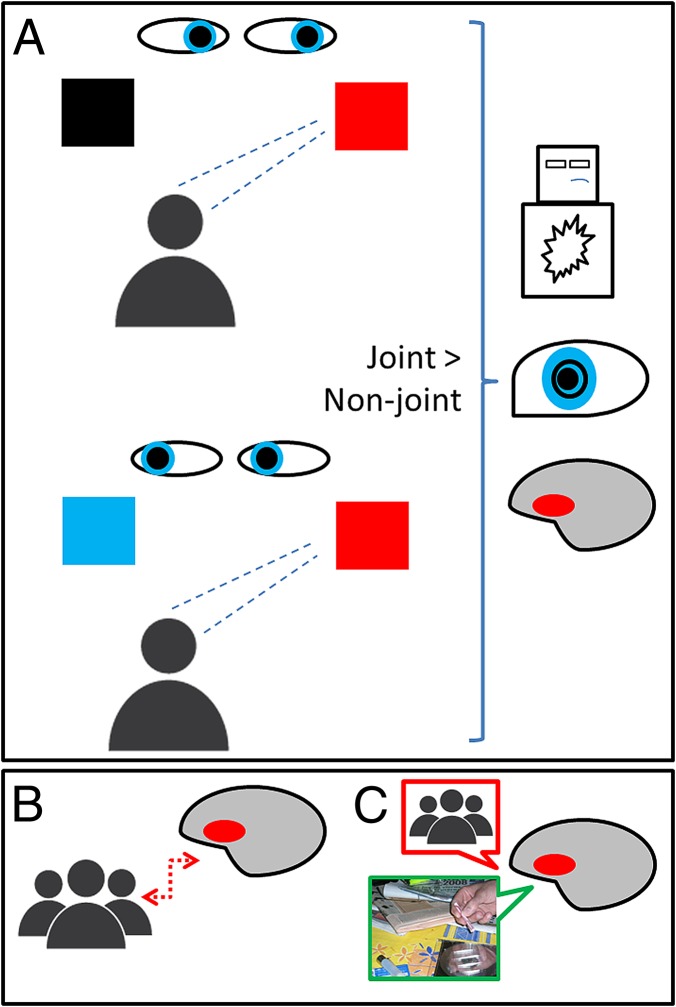

We humans have a biologically based need to form intimate personal relationships and large social networks. Social bonding is evolutionarily adaptive and powerfully rewarding, whereas social isolation often results in emotional pain and harmful behavior. However, the longing for social bonding can be dampened in some mental disorders. Cocaine addiction is a potentially chronic condition associated with social isolation and breach of social rules. At the same time, successfully recovered addicts often refer to social emotions as momentous drivers for their recovery (e.g., “could not put up with my family feeling embarrassed about me”). Despite its relevance, the cognitive deficits underlying social deterioration and the neural systems involved in social interaction and/or disruption have barely been explored in the context of addiction. In PNAS, Preller et al. (1) address these issues and demonstrate that individuals with cocaine dependence have blunted reward response to mutual social interactions, as manifested by flattened feelings of pleasantness, narrowed changes in pupil size, and reduced orbitofrontal cortex signal to joint gaze relative to nonjoint gaze interactions vis-à-vis with an anthropomorphic avatar (Fig. 1A). In agreement with the notion that we are hardwired to forming both intimate and large social networks, the activation of the orbitofrontal cortex, the key brain region for representation and weighing of reward value, was associated with the actual size of the social network of study participants (Fig. 1B). Therefore, the findings from Preller et al. compellingly suggest that cocaine addiction is associated with dampened reward response to social interaction, which ultimately impacts the richness of cocaine users’ social connections.

Fig. 1.

(A) (Left) Main conditions of the social gaze task: joint attention (the participant and the avatar direct gaze in the same direction) and nonjoint attention (the participant and the avatar direct gaze in opposite directions). (Right) Cocaine users, compared with controls, showed blunted emotional response to joint vs. nonjoint attention, as manifested across multimodal measures: subjective ratings (flattened pleasantness scores on manikin analog scales), bodily indices (narrowed changes in pupil size), and brain signal (reduced orbitofrontal cortex activation). Cocaine users also experienced abnormally increased arousal (represented in the manikin’s body) to joint relative to nonjoint attention. (B) Correlation between orbitofrontal cortex signal to joint vs. nonjoint attention and the size of participants’ real-life social networks. (C) Different value representations feedback orbitofrontal cortex decision-making systems. In cocaine users, blunted representations of social reward (red callout) coupled with heightened representations of drug reward (green callout) may persistently bias decision-making systems toward cocaine use.

These findings blend in and enrich fundamental assumptions of addiction neuroscience models. The prevailing view is that substance-related disorders represent an imbalance between the exaggerated value given to drugs (even after loss of originally strong rewarding effects) and the devalued appeal of a range of natural reinforcers, from food to sex or money (2). Various neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that cocaine-dependent users show increased activations in the main regions of the brain reward system (striatum, medial prefrontal cortex, and posterior cingulate cortex) in response to drug stimuli, coupled with significantly decreased activations in the same regions in response to sexual stimuli or monetary offers (3–5). Using an analogy, in the “addicted brain stock market,” drug stocks would be continually overrated, and all competitors steadily underrated. This uneven value ultimately feedbacks value-based decision-making systems (the previously mentioned orbitofrontal cortex being the fundamental decision center) (6, 7), which are misled to prioritize drug seeking over natural reinforcers or related long-term goals (e.g., staying healthy or saving money) (8). The study by Preller et al. experimentally demonstrates that cocaine-dependent individuals not only underrate natural personal reinforcers but also social interactions. Continuing with the previous rationale, underrated social interactions would similarly feedback value-based decision-making systems (9), explaining why social bonds and social rules may lose their power to regulate behavior in cocaine-dependent users (Fig. 1C). As a result, the prospect of social well-being (family reintegration and building or rebuilding of friendships) or the threat of social breach (harm to others and violation of law) would be less influential to guiding decisions in cocaine-dependent individuals.

The study of Preller et al. also reveals that the basic deficit behind abnormal social interaction in cocaine users is emotional. Cocaine users (unlike, for example, individuals with autism spectrum disorders) could competently generate social interactions with their counterparts, without delays and without errors. However, they missed the bulk of the emotion (in this case, reward) normally attached to the reciprocal social experience. We obtained similar conclusions from a neuroimaging study in which a group of cocaine users was challenged with a different type of social interaction task, namely moral dilemmas (e.g., “would you throw a dying person into the sea to float a lifeboat full of survivors?”). The social decisions of cocaine users were generally sound and comparable to those of controls; both groups frequently endorsed deontological or no responses. However, the analyses of brain activations showed that while pondering moral dilemmas, cocaine users, in contrast to controls, had significantly blunted activation in a set of brain regions primarily involved in emotion generation and representation, including the anterior cingulate cortex, the insula, and the midbrain periaqueductal gray (10). Both these findings can be viewed as suggestive of the existence of a basic emotional deficit impacting social cognition in cocaine addiction: Cocaine users can cognitively address social interaction tasks but fail to fully experience the positive or negative emotions that social scenarios would typically generate. Mechanistically, it has been proposed that this deficit may be accounted by either dispositional or drug-induced difficulties to trigger or to perceive the somatic markers (bodily based emotional drivers) that evolutionarily signal the most advantageous outcomes for our decisions, including those driven to secure social bonding (11). To briefly illustrate this point: If during a drug-seeking opportunity the emotional signals attached to the prospect of letting down family and friends arose (e.g., feelings of embarrassment), the chances of seeking drugs would decrease. On the other hand, if these social emotional signals were not powerful enough, even if the cognitive prospect of letting people down is evoked, the chances of seeking drugs would increase.

The findings of Preller et al. also bring back the relevance of social reward for addiction recovery. The link between decreased brain reward systems volume and response to social interaction and the size of social networks (1, 12) on addiction treatment outcomes (13) clearly advocates for nurturing of community engagement and social networking during cocaine addiction treatment. The most supported evidence-based intervention for cocaine addiction is contingency management, which is based on exchange of cocaine abstinence checks for personally relevant rewards (e.g., money vouchers) (14). The current findings emphasize the need to enhance this approach via social (reciprocal interaction based) rewards. Preclinical evidence suggests these dyadic interactions can actually work as a competent alternative reward to cocaine (15). Moreover, there is a dearth of evidence-based pharmacological treatments for cocaine addiction. Clinical trials have focused on psychostimulant substitution drugs, anti-impulsivity drugs, and cognitive enhancers, but none of them have yielded compelling outcomes (16, 17). In this regard, the current findings suggest the need to explore the novel pathway of social interaction boosters; for example, oxytocin has shown to increase the reward signal

A paramount question is whether social reward deficits are a cause or a consequence of cocaine addiction.

toward social cues in experimental studies (18). Overall, it is important to note that even the best possible behavioral or pharmacological interventions could only tackle drug use for limited time periods, whereas normalization of social bonding–derived rewards can strengthen resilience against drug intake in a longer-term perspective.

Last but not least, the study of Preller et al. raises intriguing questions for future research. A paramount question is whether social reward deficits are a cause or a consequence of cocaine addiction. This very same laboratory has provided preliminary evidence regarding this question, showing that social decision-making deficits occur in both recreational and dependent cocaine users (19), therefore suggesting social deficits are a vulnerability factor for cocaine addiction. However, it is also well known that cocaine detrimentally impacts orbitofrontal cortex functions (20), such that even recreational exposure to cocaine may impair or worsen the orbitofrontal ability to properly weigh up social bonds and social rules. Longitudinal studies are warranted to address this fascinating issue. Along the same lines, it would be relevant to determine whether social reward deficits are cocaine specific or a general characteristic of addiction or, more specifically, may these basic deficits discriminate between addictions inherently linked to major social issues vs. addictions without inherent social complications, such as smoking?

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 2842.

References

- 1.Preller KH, et al. Functional changes of the reward system underlie blunted response to social gaze in cocaine users. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:2842–2847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317090111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: Neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1642–1652. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asensio S, et al. Altered neural response of the appetitive emotional system in cocaine addiction: An fMRI Study. Addict Biol. 2010;15(4):504–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garavan H, et al. Cue-induced cocaine craving: Neuroanatomical specificity for drug users and drug stimuli. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(11):1789–1798. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein RZ, et al. Is decreased prefrontal cortical sensitivity to monetary reward associated with impaired motivation and self-control in cocaine addiction? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(1):43–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fellows LK. Orbitofrontal contributions to value-based decision making: Evidence from humans with frontal lobe damage. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1239:51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy DJ, Glimcher PW. The root of all value: A neural common currency for choice. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22(6):1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bechara A. Decision making, impulse control and loss of willpower to resist drugs: A neurocognitive perspective. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(11):1458–1463. doi: 10.1038/nn1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azzi JC, Sirigu A, Duhamel JR. Modulation of value representation by social context in the primate orbitofrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(6):2126–2131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111715109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verdejo-Garcia A, et al. Functional alteration in frontolimbic systems relevant to moral judgment in cocaine-dependent subjects [published online ahead of print July 11, 2012] Addict Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verdejo-García A, Bechara A. A somatic marker theory of addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis PA, Rezaie R, Brown R, Roberts N, Dunbar RI. Ventromedial prefrontal volume predicts understanding of others and social network size. Neuroimage. 2011;57(4):1624–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaskutas LA, Bond J, Humphreys K. Social networks as mediators of the effect of Alcoholics Anonymous. Addiction. 2002;97(7):891–900. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dutra L, et al. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):179–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zernig G, Kummer KK, Prast JM. Dyadic social interaction as an alternative reward to cocaine. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:100. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castells X, et al. Efficacy of psychostimulant drugs for cocaine dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(2):CD007380. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007380.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sofuoglu M, DeVito EE, Waters AJ, Carroll KM. Cognitive enhancement as a treatment for drug addictions. Neuropharmacology. 2013;64:452–463. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groppe SE, et al. Oxytocin influences processing of socially relevant cues in the ventral tegmental area of the human brain. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(3):172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hulka LM, et al. Altered social and non-social decision-making in recreational and dependent cocaine users [published online ahead of print July 22, 2013] Psychol Med. 2013 doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucantonio F, Stalnaker TA, Shaham Y, Niv Y, Schoenbaum G. The impact of orbitofrontal dysfunction on cocaine addiction. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(3):358–366. doi: 10.1038/nn.3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]