Abstract

Fanconi anemia complementation group F protein (FANCF) is a key factor, which maintains the function of FA/BRCA, a DNA damage response pathway. However, the functional role of FANCF in breast cancer has not been elucidated. We performed a specific FANCF-shRNA knockdown of endogenous FANCF in vitro. Cell viability was measured with a CCK-8 assay. DNA damage was assessed with an alkaline comet assay. Apoptosis, cell cycle, and drug accumulation were measured by flow cytometry. The expression levels of protein were determined by Western blot using specific antibodies. Based on these results, we used cell migration and invasion assays to demonstrate a crucial role for FANCF in those processes. FANCF shRNA effectively inhibited expression of FANCF. We found that proliferation of FANCF knockdown breast cancer cells (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S) was significantly inhibited, with cell cycle arrest in the S phase, induction of apoptosis, and DNA fragmentation. Inhibition of FANCF also resulted in decreased cell migration and invasion. In addition, FANCF knockdown enhanced sensitivity to doxorubicin in breast cancer cells. These results suggest that FANCF may be a potential target for molecular, therapeutic intervention in breast cancer.

Keywords: Fanconi anemia complementation group F protein, Breast neoplasms, Tumor cell line

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death among females, accounting for 23% of the total cancer cases and 14% of the cancer deaths (1). Despite research dedicated to elucidating the molecular mechanisms of breast cancer, the precise mechanisms of its initiation and progression are unclear.

Fanconi anemia (FA) is a rare chromosome instability syndrome that predisposes to bone marrow failure, developmental abnormalities, and a high risk for the development of cancer, such as hematological malignancies, solid tumors of the head and neck region, and gynecological tumors (2-5). The FA protein is a multifunctional protein composed of 15 of the FA complementation groups (FANC A-C, D1, D2, E, F, G, I, J, L, M, N, O, and P) (6-8), and is involved in cell cycle, DNA damage and repair, apoptosis, gene transcription, and gene stability through common FA/breast cancer susceptibility gene (BRCA) cellular pathways (9). As an adaptor protein, FANCF interacts with the FANCC/FANCE subunit through its N-terminal, and with the FANCA/FANCG subunit through its C-terminal. Thus, the FANCF subunit functions as the stabilizing component of the larger FA complex and maintains the biological functions of the FA/BRCA pathway (10). FANCF regulates the FA/BRCA pathway by maintaining the stability of FANC and FANCD2 ubiquitin activation (11). Epigenetic silencing of FANCF has been implicated in ovarian (12,13), leukemic (14), cervical (15), bladder (16), lung, and oral tumors (17). FANCF inhibition is mediated by gene promoter methylation and small interfering (si) RNAs, which can promote drug sensitivity of tumor cells (18-20). A previous study suggested that FANCF methylation was recognized in only 4 of 99 cases (4.0%) of Japanese primary breast cancer (21). Wei et al. (22) reported that FANCF methylation was rare in breast tumors: 1 of 120 (0.8%). Reports on the expression pattern of FANCF in normal and breast cancer samples are not available. Therefore, the exact role of FANCF in breast cancer remains unclear.

The purpose of the present study was to provide evidence for the role of FANCF in determining the proliferation, migration and chemosensitivity of human breast cancer by assaying cell function after FANCF knockdown. Our results demonstrated a promising therapeutic potential of FANCF shRNA for treatment of breast cancer.

Material and Methods

Cell culture

Estrogen receptor alpha (ERα)-positive human breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 (BRCA1/2-wild type) and ERα-negative MDA-MB-435S cells (BRCA1/2-wild type) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Adherent cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies against FANCF and FANCD2 were from Abcam Inc. (USA). Doxorubicin (Dox), and low and normal melting point (LMP and NMP) agarose gels were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (USA).

Construction of the FANCF shRNA expression vector

The FANCF shRNA expression vector was used to achieve specific down-regulation of FANCF. In brief, DNA vectors expressing the shRNA forms were generated using pSilencer 4.1-CMV plasmids (Ambion, USA). The sequence of the oligonucleotides used to construct FANCF shRNA expressing vector was designed (GenBank accession No. NM022725.3) as follows: sense: 5′-GATCCGCTTCCTGAAGGTGATAGCGTTCAAGAGACGCTATCACCTTCAGGAAGTTTTTTGGAAA-3′ and antisense: 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAACTTCCTGAAGGTGATAGCGTCTCTTGAACGCTATCACCTTCAGGAAGCG-3′. A scrambled shRNA with no significant homology to human gene sequences was used as a negative control to detect nonspecific effects.

FANCF shRNA transient transfection

Cells were seeded onto 6-well plates (3×105 cells/well) or 100-mm dishes (2×106 cells) and were allowed to adhere for 24 h. Then, cells were transfected with the pSilencer 4.1-CMV (Ambion) control shRNA vector (control shRNA, 20 μM) or pSilencer 4.1-CMV FANCF shRNA vector (FANCF shRNA, 20 μM) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 4 h, the culture medium was replaced with fresh media supplemented with 10% FBS, and the cells were harvested at 24 and 48 h after transfection.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis for the presence of specific proteins or for phosphorylated forms of proteins was performed on whole-cell sonicates and lysates from MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S cells. Protein (30-50 μg) was mixed 4:1 with 5× sample buffer (20% glycerol, 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.05% bromophenol blue, and 1.25 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, all from Sigma). Equal amounts of protein were loaded onto a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. Cell proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes. The PVDF membranes were then blocked with 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 and then incubated with an appropriate dilution of antibodies (1:1000 to 1:2000) overnight at 4°C. The blots were washed and incubated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-IgG antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA). Immunocomplexes were visualized by chemiluminescence using ECL (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed using Cell Count Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., USA). Cells were seeded at 5×103 cells/well on 96-well plates and allowed to grow in the growth medium for 24 h. Cells were transfected with control or FANCF shRNA for 24 and 48 h, and then treated with Dox at different concentrations (0.1, 1, 5, 10, 20, and 40 nM) for 24 h. Ten microliters of CCK-8 solution was added to 100 µL media in each well and absorbance was determined at 450 nm after 1 h of incubation at 37°C.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry analysis was performed on a FACSCalibur instrument (Becton-Dickinson, USA). For determination of cell cycle by exclusion of propidium iodide (PI), 500 µL cell culture was incubated with 30 µg/mL PI for 1 h at room temperature prior to analysis. For determination of apoptotic cells, cells were harvested, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), incubated for 15 min at room temperature with a solution of fluorescence isothiocyanate-conjugated Annexin V (2.5 μg/mL) and PI (5 μg/mL) (all from Sigma), and then analyzed for apoptosis. The assay for Dox accumulation was performed as described previously (23), with some modifications. Briefly, Dox was added to cells to a final concentration of 10 nM. The cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C with 5% CO2 in the dark. After the influx step, the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS. The analysis was performed with a flow cytometer.

Comet assay

Single-cell gel electrophoresis (comet assay) was performed essentially according to the procdure of Singh et al. (24-26). A freshly prepared suspension of cells on 1% LMP agarose dissolved in PBS was spread onto microscope slides precoated with 0.6% NMP agarose. The cells were then lysed for 1 h at 4°C in a buffer consisting of 2.5 M NaCl, 100 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM Tris, pH 10. After lysis, the slides were placed in an electrophoresis unit and the DNA was allowed to unwind for 40 min in the electrophoresis solution consisting of 300 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA, pH >13. Electrophoresis was conducted at 4°C (the temperature of the running buffer did not exceed 12°C) for 20 min at 25 V and 300 mA. The slides were then neutralized with 0.4 M Tris, pH 7.5, stained with 2.5 mM PI and covered with coverslips. To prevent additional DNA damage, all the steps described above were conducted under dimmed light or in the dark. Five hundred randomly chosen cells per slide were scanned and analyzed automatically using the Comet Assay Software Project (CASP) 1.01. Mean DNA tail lengths were calculated for ∼400 cells.

Cell migration and invasion

Cell migration was assayed by wound healing assays. Cells were grown to confluency, and then a scratch wound was made in the monolayer by dragging a 1-mL pipette tip across the layer. Cells were cultured as described above, and wound closure was followed by microscopy at 48 h after wound infliction. Experiments were repeated three times. Cell invasion was investigated in Matrigel (BD Biosciences, USA). In brief, 3×104 cells in 100 μL DMEM containing 0.2% fetal bovine serum albumin were seeded onto the upper chambers of 8-μM pore transwell chambers. For assay of invasion through a Matrigel barrier, cells were allowed to migrate for 5 h for the migration assays. Migrated cells from six random fields were fixed, stained, counted, and averaged. Experiments were repeated three times. To determine the effect of FANCF shRNA on cell migration and invasion, cells were treated with FANCF shRNA for 48 h in medium containing 10% FCS.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as means±SD. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with post hoc analysis. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical tests were carried out using the SPSS 11.5 software package (SPSS Inc., USA).

Results

FANCF expression was suppressed in breast cancer cells by RNA interference (RNAi)

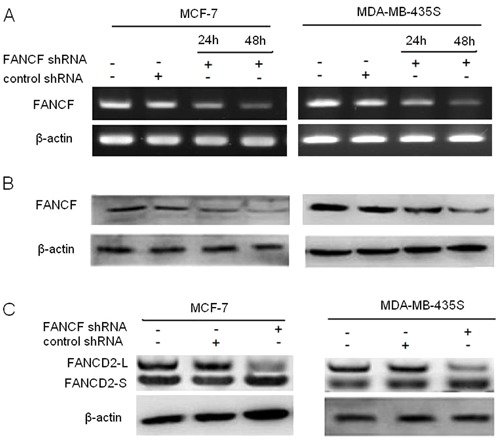

To determine if FANCF can serve as a novel therapeutic target for breast cancer, we first used shRNA to knock down FANCF expression in breast cancer cells. To verify the results of gene silencing, FANCF expression was detected by RT-PCR and Western blotting at 24 and 48 h post-transfection. Expression of FANCF in the two cell lines (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S) was inhibited in a time-dependent manner compared with the control (cells treated with scrambled shRNA) (Figure 1A and B). The results confirmed that FANCF expression was inhibited by transfection with shRNA targeting FANCF.

Figure 1. Inhibition of FANCF mRNA and protein levels by RNA interference. A, FANCF mRNA was measured in conditioned media from FANCF-shRNA-transfected cells using RT-PCR. B, Western blot analysis of FANCF protein expression in cell lysates from MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S cells transfected with FANCF-shRNA. C, Representative FANCF and FANCD2 blots. (FANCD2-L: mono-ubiquitinated; FANCD2-S: nonubiquitinated).

The mono-ubiquitination of FANCD2 is a key step in activating the FA/BRCA pathway. To observe the effect of FANCF shRNA on the FA/BRCA pathway function, we detected the level of FANCD2 ubiquitination at 48 h after transfection. We found that gene silencing of FANCF also decreased the expression of FANCD2-L and reduced the level of FANCD2 monoubiquitination (Figure 1C), However, the expression of FANCD2-S was not reduced in comparison with FANCD2-L in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S cells, although the total amount of FANCD2 appeared slightly reduced. Therefore, these changes suggested that inactivation of the FA/BRCA-signaling pathway was induced in breast cancer cells by FANCF shRNA.

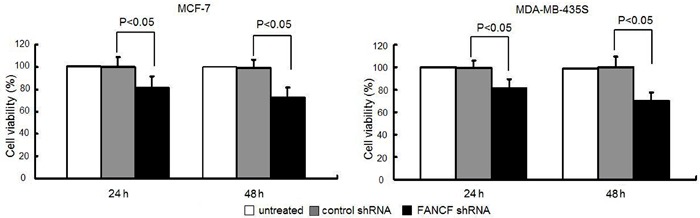

Silencing of FANCF inhibited cell proliferation in breast cancer cells

To determine whether FANCF shRNA actually affects proliferation of breast cancer cells, we examined the proliferation of MCF-7 cells and MDA-MB-435S cells (normal FANCF expression) in response to FANCF shRNA treatment. As shown in Figure 2, after gene silencing of FANCF, cell viability rates were 81.2±10.2 and 73.3±8.6% of the control cells in MCF-7 cells, and 82.9±7.3 and 70.2±7.9% in MDA-MB-435S cells at 24 and 48 h post-transfection. FANCF shRNA significantly decreased the proliferation of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S cells compared with the control cells. The results suggested that FANCF-specific shRNA could significantly inhibit proliferation of the breast cancer cells.

Figure 2. FANCF shRNA inhibits cell proliferation in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S cells. Cells were transfected with FANCF shRNA and control shRNA for 24 and 48 h. Cell viability was determined by the CCK-8 kit. Data are reported as means±SD of three independent experiments in triplicate. ANOVA followed by the post hoc test was used for statistical analyses.

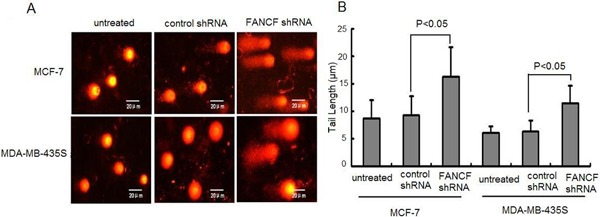

Silencing of FANCF enhanced DNA damage in breast cancer cells

Since FANCF plays important roles in DNA damage repair (27), we thus assessed the effect of FANCF shRNA on DNA damage using the alkaline comet assay. Silencing of FANCF in breast cancer cell lines led to significantly increased DNA damage compared with the cells treated with control shRNA (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Silencing of FANCF enhanced DNA damage in breast cancer cells. A, Single-cell gel electrophoresis (comet assay) showed detectable comet tails when visualized under a fluorescent microscope, indicative of DNA damage. B, Quantification of DNA fragmentation in the indicated cell lines. Data are reported as means±SD of three independent experiments in triplicate. ANOVA followed by the post hoc test was used for statistical analyses.

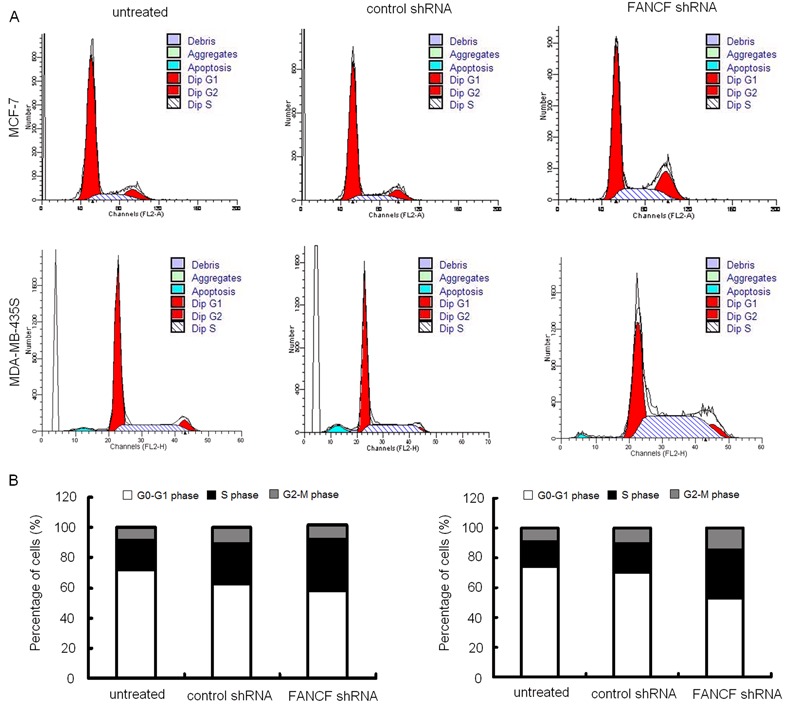

Silencing of FANCF induced cell cycle arrest (S arrest) and apoptosis in breast cancer cells

Suppression of cancer cell proliferation can be caused by arrest of cell cycle progression (28). The effect of FANCF shRNA on the cell cycle was studied by flow cytometry. FANCF shRNA influenced the cell cycle as shown in Figure 4. FANCF silencing resulted in enrichment of breast cancer cells in S phase with a concomitant decrease in number of cells in G0/G1 and G2/M phases. Taken together, these results showed that FANCF shRNA caused cell cycle alterations with S arrest.

Figure 4. FANCF-shRNA resulted in changes of cell-cycle distribution in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S cells. Flow cytometry analysis of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S cell cycles after transfection with FANCF shRNA or control shRNA for 48 h. A, One representative experiment is shown. B, Quantitative analysis of different cell phase populations. Data are reported as mean percentages of three independent experiments in triplicate.

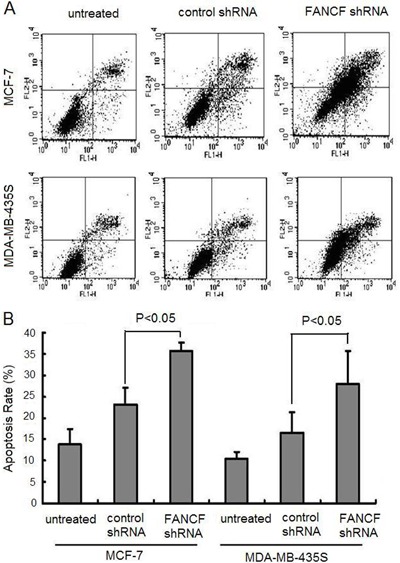

The percentage of apoptotic cells were assessed by Annexin V-FITC and PI staining, followed by flow cytometric analysis. It was observed that FANCF shRNA increased the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis compared to the untreated cells or control shRNA treated cells (P<0.05; Figure 5).

Figure 5. Apoptosis of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S cells after transfection with FANCF-shRNA for 48 h. A, Apoptosis of cells was measured using FACScan after staining with FITC-Annexin V and propidium iodide. Cells in the lower right-hand quadrant are early apoptotic cells with exposed phosphatidylserine (FITC-Annexin V-positive) but intact membrane (propidium iodide-negative). B, Quantification of apoptosis in the indicated cell lines. Data are reported as means±SD of three independent experiments in triplicate. ANOVA followed by the post hoc test was used for statistical analyses.

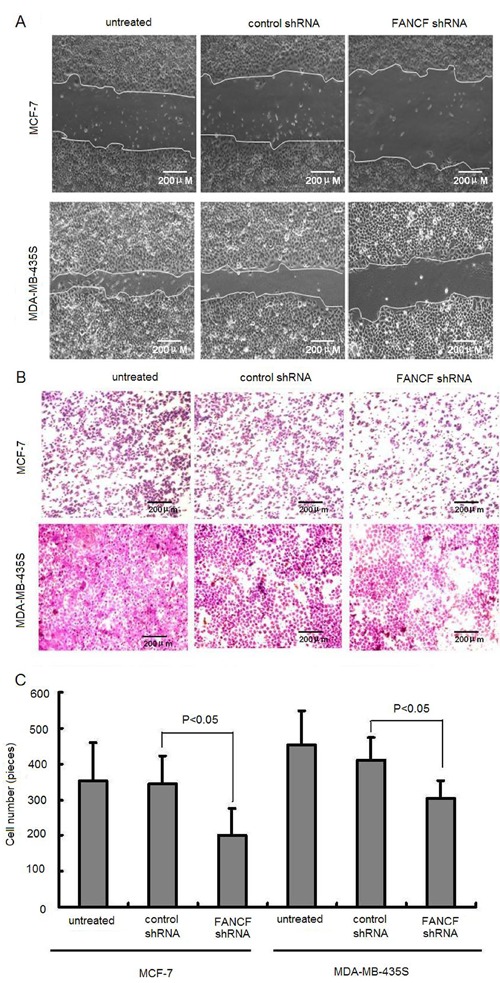

Silencing of FANCF decreased cell invasion and migration in breast cancer cells

We next investigated whether silencing of FANCF could influence invasion and migration. In vitro wound healing assays showed that wound repair in MCF-7/FANCF shRNA and MDA-MB-435S/FANCF shRNA was delayed compared with MCF-7/control and MDA-MB-435S/control cells (Figure 6A). Also, we performed a transwell analysis, as shown in Figure 6B and C. FANCF shRNA induced a significant decrease of invasiveness compared with untreated cells and control shRNA-transfected cells. These data demonstrate the tumorigenic properties of FANCF in regulating cell proliferation and migration.

Figure 6. Silencing of FANCF suppressed migration and invasion in breast cancer cells. A, Representative image of wound healing assay of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S at 48 h after wound scratch. B, Representative images for invasiveness of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S cells that migrated through transwell membranes with matrigel. C, Invasiveness of cells evaluated by counting cells that migrated through transwell membranes with matrigel. Data are reported as means±SD of three independent experiments in triplicate. ANOVA followed by the post hoc test was used for statistical analyses.

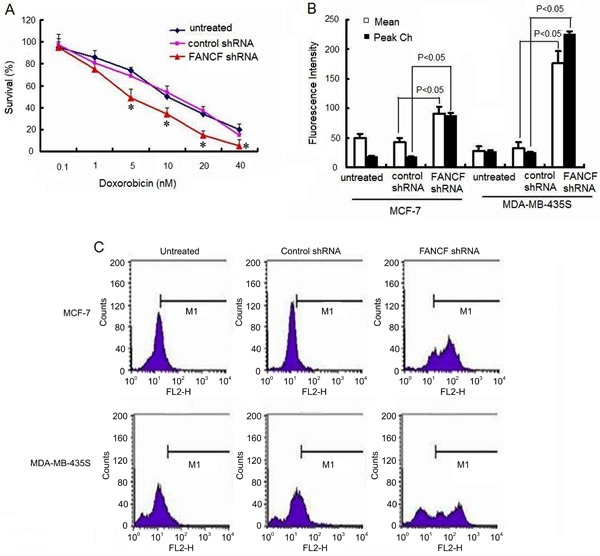

Silencing of FANCF resulted in increased chemosensitivity to Dox in breast cancer cells

We determined whether inhibition of FANCF affected the sensitivity of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S cells to the anti-tumor drug Dox. As shown in Figure 7A, compared with the control, FANCF shRNA significantly enhanced the Dox-induced decrease in the cell viability in both cell lines (P<0.05), suggesting that knockdown of FANCF significantly potentiated the cytotoxic effects of Dox on breast cancers.

Figure 7. Effects of FANCF-specific shRNA on Dox sensitivity of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S cells. A, Cells were treated with various concentrations of Dox. Cell viability was determined with a CCK-8 kit. The percentage of viable cells was determined by the ratio of viable cells treated with FANCF shRNA or control shRNA to that with no treatment. B, Median fluorescence intensity was measured indicating the relative amount of Dox accumulation. C, Effects of FANCF shRNA on cellular Dox accumulation. Cells were transfected with FANCF shRNA or control shRNA for 48 h following a 24-h incubation with 10 nM Dox. Cellular uptake of Dox was measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Data are reported as means±SD of three independent experiments in triplicate. *P<0.05, ANOVA followed by the post hoc test.

We next examined the effects of FANCF silencing on Dox accumulation in breast cancer cells. After 24-h treatment with 10 nM Dox, the amount of Dox accumulation in both cell lines increased remarkably in the FANCF-silenced cells compared with that in the control cells (P<0.05; Figure 7B and C). These results further suggested that FANCF silencing potentiated the chemosensitivity of breast cancer cells to Dox.

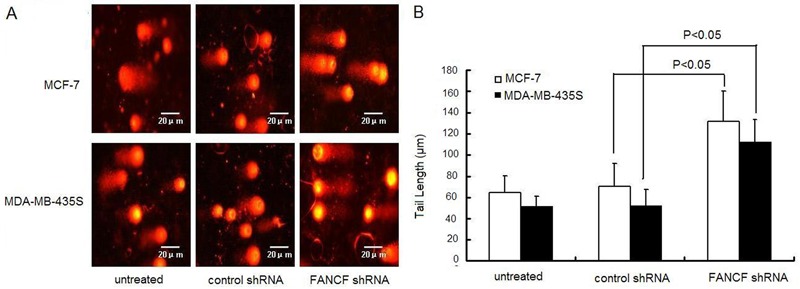

FANCF silencing increased Dox-induced DNA damage in breast cancer cells

Since FANCF silencing enhanced the antiproliferative effect of Dox in breast cancer cells, we hypothesized that FANCF silencing alters Dox-induced DNA damage, which is the main cytotoxic effect of Dox. Using the comet assay again, we found that FANCF-silenced breast cancer cells and the control cells following treatment with Dox exhibited extensive DNA damage reflected by the tail length of the comet. In addition, the FANCF-silenced cells were found to have increased DNA damage as indicated by fragmentation and the longer tail length of the comet compared with the control cells (P<0.05) following Dox treatment (Figure 8A and B). These findings suggest that FANCF silencing increased the Dox-induced cellular DNA damage.

Figure 8. FANCF silencing increased Dox-induced DNA damage in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S breast cancer cells. A, Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with 10 nM Dox for 24 h and examined by single-cell gel electrophoresis (comet assay), which showed increased DNA damage in the form of DNA fragmentation visualized under a fluorescence microscope. B, Quantification of tail lengths (µm) of the comet from 30 comets for each group. Data are reported as means±SD of three independent experiments in triplicate. ANOVA followed by the post hoc test was used for statistical analyses.

Discussion

FANCF is a key molecule in a wide range of cancers, and identifying its functional role in breast cancer has important clinical implications. RNAi is a promising new experimental tool for the analysis of gene function and has become a key gene therapy technique in mammalian systems. Compared with traditional gene therapy, RNAi possesses the advantages of exquisite precision and high efficacy in down-regulating gene expression. It has been reported that both chemically synthetic and vector-based siRNA can successfully knock down specific gene expression in mammalian cells, including malignant cells. Here, vectors expressing shRNA for FANCF significantly inhibited the expression of FANCF in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435S cells.

Central to the FA/BRCA pathway is the mono-ubiquitination of FANCD2, which connects upstream signaling with downstream enzymatic repair steps and activates the function of this pathway (29). Thus, the mono-ubiquitination and focus formation of FANCD2 are surrogate markers for FA/BRCA pathway activation. In our present study, gene silencing of FANCF in breast cancer cells blocked the FA/BRCA pathway as evidenced by reducing the level of FANCD2 mono-ubiquitination. It has been reported that FANCF plays an important role in stabilizing subunits of the FA complex and contributes to the proper function of FA/BRCA pathway (11). The most important findings of the present study are that FANCF inhibition is associated with decreased proliferation, migration, invasion potential, and resistance to Dox, suggesting that FANCF could be a promising therapeutic target.

Our results demonstrate that FANCF shRNA exerts robust antitumor activity by promoting apoptosis and DNA damage. It is unclear how FANCF depletion triggers apoptosis in breast cancer cells. The reason may be that FA/BRCA pathway dysfunction caused by FANCF silencing leads to reduction of DNA repair and DNA instability, and then induces apoptosis and DNA fragmentation in tumor cells.

The association of the cell cycle with cell survival has been seen in many human cancers. We observed that treatment of breast cancer cells with FANCF shRNA resulted in S-phase arrest of cell cycle progression, suggesting that the rapid accumulation of cells in the replication phase and the distinct cell cycle distribution pattern contributed to the decreased proliferation rate in FANCF-silenced breast cancer cells.

Efficient DNA repair in cancer cells is an important mechanism of therapeutic resistance, and inhibition of DNA repair pathway would be expected to make tumor cells more sensitive to DNA damage caused by chemotherapy agents. Dox is one of most effective drugs currently available for the treatment of neoplastic diseases. We found that FANCF shRNA enhanced the cell killing effects of Dox in breast cancer cells, and that this combination greatly increased Dox accumulation in breast cancer cells. This observation is consistent with earlier reports by our group. We reported that FANCF silencing-induced dysfunction of the FA/BRCA pathway increases sensitivity of human breast cancer cell line to mitoxantone (MX) (30). Both Dox and MX can cause double-strand breaks (DSBs) indirectly through poisoning of topoisomerase II, therefore monitoring FANCF expression may aid in the identification of tumors that are sensitive to these agents. Taken together, this study demonstrates the therapeutic potential of FANCF shRNA for treating breast cancer.

Kusayanagi et al. (31) identified FANCF as a Dox-binding protein and found that Dox inhibited the monoubiquitination of FANCD2, which is required for FANCD2 loading onto chromatin in response to DNA damage. We observed the FANCF knockdown sensitized Dox cytotoxicity. Further experiments are required to confirm whether FANCF knockdown affects the Dox-FANCF interaction. On the other hand, Dox can directly affect different stages of the DNA replication process. Tumini et al. (32) reported that FANCF physically interacts with PSF2, a member of the GINS complex essential for both the initiation and elongation steps of DNA replication. In light of this observation, it is tempting to hypothesize that the FANCF knockdown-sensitizing effect of Dox is related to its role in DNA replication. This hypothesis needs experimental validation.

The FA/BRCA pathway plays an important role in DNA repair (33). In the present study, the comet assay was used to detect Dox-induced DNA damage of breast cancer cells; FANCF silencing increased the Dox-induced cellular DNA damage. One possible explanation is that the DNA damage repair function of the FA/BRCA pathway was disrupted by FANCF interference in breast cancer cells, resulting in the decreased repair function of Dox-induced DNA damage.

Dox induces formation of DNA DSBs (34-36). In FANCF-deficient cancer cells, the repair of DSBs by homologous recombination is damaged, thus rendering the cancer cells highly sensitive to alternative DSB repair pathways, such as nonhomologous end-joining single-strand annealing (37). Therefore, blockade of the alternative DSB repair pathway in the FANCF-deficient cancers represents a synthetic lethal treatment for FANCF-deficient cancers. In this study, we found that knockdown of FANCF potentiates the sensitivity of breast cancer cells to Dox. This could result from the synthetic lethal interaction of Dox with the DSBR pathway. Thus, Dox can be more toxic to FANCF-deficient cancer cells compared to healthy cells, since FANCF-deficient cancers lack the necessary DNA repair pathways that promote survival in healthy cells.

It has been shown that FANCF promoter hypermethylation is common in ovarian (12,13), leukemia (14), cervical (15), bladder (16), lung, and oral tumors (17). FANCF inhibition mediated by gene promoter methylation can also promote drug sensitivity of ovarian cancer, multiple myeloma and glioma cells (18-20). The results of this study suggest that FANCF inhibition might be a potential strategy for augmenting chemotherapy in tumors. In an extension of our findings regarding a possible role for FANCF in regulating proliferation and drug sensitivity, we also demonstrated that FANCF has profound effects on breast cancer cell migration and invasiveness in vitro.

From a therapeutic standpoint, the inhibition of breast cancer proliferation, migration and invasion in vitro by FANCF silencing, but yet chemosensitizing Dox, could perhaps translate into better control of tumor dispersal in vivo, a hallmark of malignant breast cancer. Further preclinical testing will address whether some or all these in vitro effects are also seen in vivo and whether FANCF could be developed into an effective and safe chemosensitizer of breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

Research supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (#30873097, #81173092 and #81202551) and by the Liaoning Province Scientific Research Foundation of China (#2011415052, #L2011127).

Footnotes

First published online December 12, 2013.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niedernhofer LJ, Lalai AS, Hoeijmakers JH. Fanconi anemia (cross)linked to DNA repair. Cell. 2005;123:1191–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auerbach AD. Fanconi anemia and its diagnosis. Mutat Res. 2009;668:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Andrea AD. Susceptibility pathways in Fanconi's anemia and breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1909–1919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0809889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hucl T, Gallmeier E. DNA repair: exploiting the Fanconi anemia pathway as a potential therapeutic target. Physiol Res. 2011;60:453–465. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.932115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaz F, Hanenberg H, Schuster B, Barker K, Wiek C, Erven V, et al. Mutation of the RAD51C gene in a Fanconi anemia-like disorder. Nat Genet. 2010;42:406–409. doi: 10.1038/ng.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim Y, Lach FP, Desetty R, Hanenberg H, Auerbach AD, Smogorzewska A. Mutations of the SLX4 gene in Fanconi anemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43:142–146. doi: 10.1038/ng.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoepker C, Hain K, Schuster B, Hilhorst-Hofstee Y, Rooimans MA, Steltenpool J, et al. SLX4, a coordinator of structure-specific endonucleases, is mutated in a new Fanconi anemia subtype. Nat Genet. 2011;43:138–141. doi: 10.1038/ng.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bogliolo M, Lyakhovich A, Callen E, Castella M, Cappelli E, Ramirez MJ, et al. Histone H2AX and Fanconi anemia FANCD2 function in the same pathway to maintain chromosome stability. EMBO J. 2007;26:1340–1351. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyakhovich A, Surralles J. New roads to FA/BRCA pathway: H2AX. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1019–1023. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.9.4223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leveille F, Blom E, Medhurst AL, Bier P, Laghmani el H, Johnson M, et al. The Fanconi anemia gene product FANCF is a flexible adaptor protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39421–39430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim SL, Smith P, Syed N, Coens C, Wong H, Burg M van der, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of FANCF and outcome in advanced ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1452–1456. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z, Li M, Lu S, Zhang Y, Wang H. Promoter hypermethylation of FANCF plays an important role in the occurrence of ovarian cancer through disrupting Fanconi anemia-BRCA pathway. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:256–260. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.3.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tischkowitz M, Ameziane N, Waisfisz Q, Winter JP de, Harris R, Taniguchi T, et al. Bi-allelic silencing of the Fanconi anaemia gene FANCF in acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2003;123:469–471. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narayan G, Arias-Pulido H, Nandula SV, Basso K, Sugirtharaj DD, Vargas H, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of FANCF: disruption of Fanconi anemia-BRCA pathway in cervical cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2994–2997. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neveling K, Kalb R, Florl AR, Herterich S, Friedl R, Hoehn H, et al. Disruption of the FA/BRCA pathway in bladder cancer. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2007;118:166–176. doi: 10.1159/000108297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsit CJ, Liu M, Nelson HH, Posner M, Suzuki M, Kelsey KT. Inactivation of the Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway in lung and oral cancers: implications for treatment and survival. Oncogene. 2004;23:1000–1004. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olopade OI, Wei M. FANCF methylation contributes to chemoselectivity in ovarian cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:417–420. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Q, Van der Sluis PC, Boulware D, Hazlehurst LA, Dalton WS. The FA/BRCA pathway is involved in melphalan-induced DNA interstrand cross-link repair and accounts for melphalan resistance in multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2005;106:698–705. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen CC, Taniguchi T, D'Andrea A. The Fanconi anemia (FA) pathway confers glioma resistance to DNA alkylating agents. J Mol Med. 2007;85:497–509. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tokunaga E, Okada S, Kitao H, Shiotani S, Saeki H, Endo K, et al. Low incidence of methylation of the promoter region of the FANCF gene in Japanese primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2011;18:120–123. doi: 10.1007/s12282-009-0175-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei M, Xu J, Dignam J, Nanda R, Sveen L, Fackenthal J, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha, BRCA1, and FANCF promoter methylation occur in distinct subsets of sporadic breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111:113–120. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9766-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shukla A, Hillegass JM, MacPherson MB, Beuschel SL, Vacek PM, Pass HI, et al. Blocking of ERK1 and ERK2 sensitizes human mesothelioma cells to doxorubicin. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:314. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh NP, McCoy MT, Tice RR, Schneider EL. A simple technique for quantitation of low levels of DNA damage in individual cells. Exp Cell Res. 1988;175:184–191. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(88)90265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klaude M, Eriksson S, Nygren J, Ahnstrom G. The comet assay: mechanisms and technical considerations. Mutat Res. 1996;363:89–96. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(95)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren X, Lim S, Ji Z, Yuh J, Peng V, Smith MT, et al. Comparison of proliferation and genomic instability responses to WRN silencing in hematopoietic HL60 and TK6 cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kowal P, Gurtan AM, Stuckert P, D'Andrea AD, Ellenberger T. Structural determinants of human FANCF protein that function in the assembly of a DNA damage signaling complex. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2047–2055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608356200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta SC, Kim JH, Prasad S, Aggarwal BB. Regulation of survival, proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis of tumor cells through modulation of inflammatory pathways by nutraceuticals. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:405–434. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9235-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Higuera I, Taniguchi T, Ganesan S, Meyn MS, Timmers C, Hejna J, et al. Interaction of the Fanconi anemia proteins and BRCA1 in a common pathway. Mol Cell. 2001;7:249–262. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Zhao L, Sun H, Yu J, Li N, Liang J, et al. Gene silencing of FANCF potentiates the sensitivity to mitoxantrone through activation of JNK and p38 signal pathways in breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kusayanagi T, Tsukuda S, Shimura S, Manita D, Iwakiri K, Kamisuki S, et al. The antitumor agent doxorubicin binds to Fanconi anemia group F protein. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:6248–6255. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tumini E, Plevani P, Muzi-Falconi M, Marini F. Physical and functional crosstalk between Fanconi anemia core components and the GINS replication complex. DNA Repair. 2011;10:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothfuss A, Grompe M. Repair kinetics of genomic interstrand DNA cross-links: evidence for DNA double-strand break-dependent activation of the Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:123–134. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.123-134.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tewey KM, Rowe TC, Yang L, Halligan BD, Liu LF. Adriamycin-induced DNA damage mediated by mammalian DNA topoisomerase II. Science. 1984;226:466–468. doi: 10.1126/science.6093249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swift LP, Rephaeli A, Nudelman A, Phillips DR, Cutts SM. Doxorubicin-DNA adducts induce a non-topoisomerase II-mediated form of cell death. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4863–4871. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cutts SM, Rephaeli A, Nudelman A, Hmelnitsky I, Phillips DR. Molecular basis for the synergistic interaction of adriamycin with the formaldehyde-releasing prodrug pivaloyloxymethyl butyrate (AN-9) Cancer Res. 2001;61:8194–8202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashworth A. A synthetic lethal therapeutic approach: poly(ADP) ribose polymerase inhibitors for the treatment of cancers deficient in DNA double-strand break repair. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3785–3790. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.0812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]