Abstract

Background

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a primary disorder characterised by asymmetric thickening of septum and left ventricular wall, with a prevalence of 0.2% in the general population.

Objective

To describe a novel mitochondrial DNA mutation and its association with the pathogenesis of HCM.

Methods and results

All maternal members of a Chinese family with maternally transmitted HCM exhibited variable severity and age at onset, and were implanted permanent pacemakers due to complete atrioventricular block (AVB). Nuclear gene screening (MYH7, MYBPC3, TNNT2 and TNNI3) was performed, and no potential pathogenic mutation was identified. Mitochondrial DNA sequencing analysis identified a novel homoplasmic 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation. This mutation was exclusively present in maternal members and absent in non-maternal members. Conservation index by comparison to 16 other vertebrates was 94.1%. This mutation disturbs the 2336U-A2438 base pair in the stem–loop structure of 16S rRNA domain III, which is involved in the assembly of mitochondrial ribosome. Oxygen consumption rate of the lymphoblastoid cells carrying 2336T>C mutation had decreased by 37% compared with controls. A reduction in mitochondrial ATP synthesis and an increase in reactive oxidative species production were also observed. Electron microscopic analysis indicated elongated mitochondria and abnormal mitochondrial cristae shape in mutant cells.

Conclusions

It is suggested that the 2336T>C mutation is one of pathogenic mutations of HCM. This is the first report of mitochondrial 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation and an association with maternally inherited HCM combined with AVB. Our findings provide a new insight into the pathogenesis of HCM.

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a primary disorder characterised by asymmetric thickening of the septum and left ventricular wall. In particular, HCM has a prevalence of 0.2% in the general population.1 HCM is the most common cause of sudden cardiac death in individuals younger than 35 years.2 Left ventricular remodelling with changes in wall thickness and cavity size occurs in a variety of cardiac diseases.3–5 In the HCM population, about 10% of patients6 7 progress to dilated cardiomyopathy with left ventricular remodelling by end stage HCM, which finally results in severe heart failure. Atrioventricular block (AVB) is a major reason for pacemaker implantation, which occurs when atrial depolarisation fails to reach the ventricles or is conducted with a delay.8 The pathogenesis of HCM remains poorly understood because of multifactorial causes, including hereditary and environmental factors. Familial HCM is inherited mainly as an autosomal-dominant trait and is attributed to mutations of sarcomeric genes. Cardiac β-myosin heavy chain (MYH7), cardiac myosin-binding protein C (MYBPC3), cardiac troponin T (TNNT2) and cardiac troponin I3 (TNNI3) together account for more than 75% of all HCM cases.9 Meanwhile, the maternal transmissions of HCM have been implicated in some pedigrees. This suggests that a mutation in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is one of the molecular bases for this disorder.10 11 The first mtDNA point mutation associated with HCM was identified in the gene tRNALeu(UUR) in 1991.12 Since then, several mutations have been reported to be associated with HCM.11 Our recent report showed that a mitochondrial ND5 12338T>C variant is associated with maternally inherited HCM in a Chinese pedigree.13 In HCM, the pathogenesis mtDNA include mitochondrial tRNAs and protein encoding genes, while mutations in mitochondrial rRNAs have rarely been reported. Meanwhile, the molecular pathogenesis of HCM in the Chinese population remains poorly understood.

In continued efforts to understand the role of the mitochondrial genome in the pathogenesis of HCM in the Chinese population, a systematic and extended mutational screening of mtDNA has been initiated in HCM subjects at the Cardiovascular Clinic in the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, China. In the present study, we performed the clinical, genetic and molecular characterisation of a Han Chinese family with maternally inherited HCM. In this family, all (4/4) maternal members were affected with HCM combined with AVB, which is a rare phenomenon in the HCM population. Mutational analysis of the mitochondrial genome identified a novel homoplasmic 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation, which presented exclusively in all the maternal members of this family. The 2336T>C mutation was evaluated by phylogenetic analysis, structure–function relationships and allelic frequency in control individuals. Furthermore, functional assays of the 2336T>C mutation were conducted through determination of mitochondrial oxygen consumption capacity, mitochondrial ATP synthesis and reactive oxidative species (ROS) production in lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from the maternal members carrying this mutation as compared with the controls. Mitochondrial ultrastructure was also observed by electron microscopy. The results indicated a mitochondrial defect in cell lines derived from maternal members.

Materials and methods

Subjects

We ascertained a Chinese family (figure 1) through the Cardiovascular Clinic in the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, China. Informed consent, blood, urine (epithelial-like cells detached from tubules), hair follicle and oral epithelium samples, and clinical evaluations were obtained from all of the participating family members. All protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, China. Members of this pedigree were interviewed and evaluated to identify both personal or medical histories of HCM and other clinical abnormalities. The 350 control individuals with matched age and sex were recruited from a panel of unaffected, genetically unrelated Han Chinese individuals in the same region.

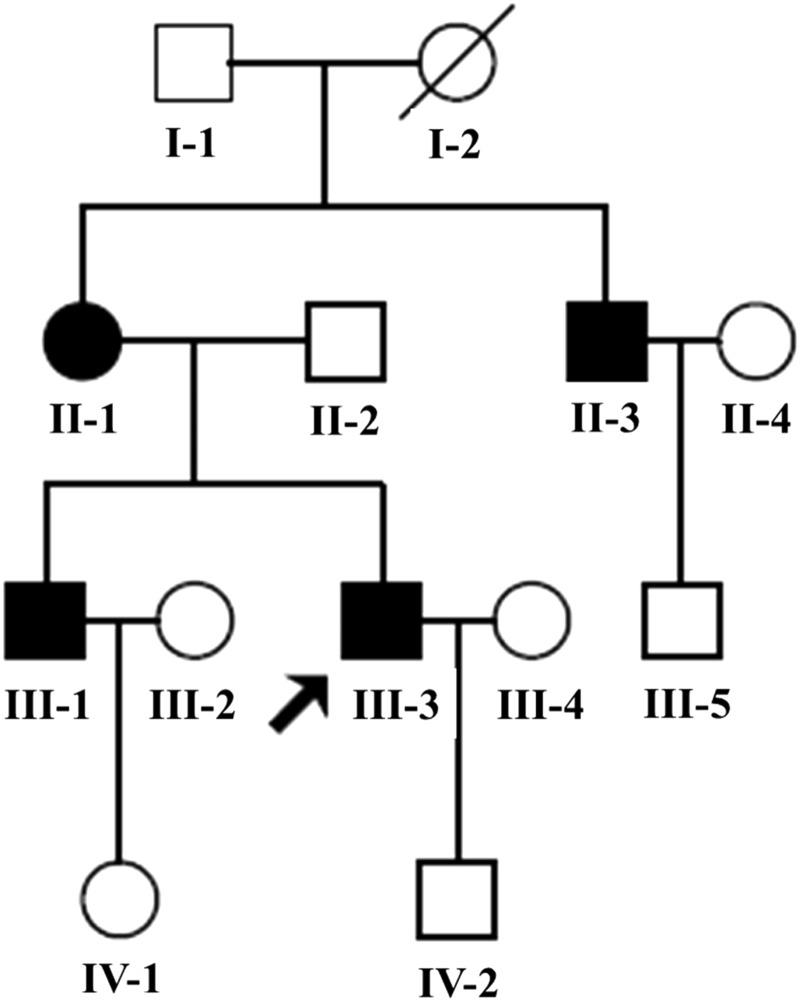

Figure 1.

The Chinese pedigree with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Affected individuals are indicated by the filled symbols. The arrowhead denotes the proband.

Clinical evaluations

Evaluations of the proband III-3 and relatives were taken with different methods of assessment, including medical history, physical examination and laboratory tests (routine urine and blood test and lactic acid samples from whole venous blood). M-mode two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography (ECHO) (PHILIPS, SONOS 5500) and 12-lead ECG (Beijing FUTIAN, FX-3010) analysis were also conducted as described previously.14–18

The clinical diagnosis of HCM was based on echo by demonstrating an unexplained left ventricular hypertrophy, that is, maximum LV wall thickness (MLVWT) ≥13 mm and typically asymmetric in distribution (IVS/left posterior wall thickness (LPW) ≥ 1.3).8 19 Subjects with hypertrophy from other cardiovascular disease (eg, hypertension or aortic stenosis) or systemic disease were excluded. The definition of non-obstructive HCM was left ventricular outflow tract gradient (LVOTG) at rest <30 mm Hg.20

Mutational analysis of the mitochondrial genome

Genomic DNA was isolated from the whole blood of participants using a TaKaRa Blood Genome DNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa Biotechnology). The entire mtDNA of the proband (III-3) and his mother (II-1), uncle (II-3) and brother (III-1) were PCR amplified and sequenced in 24 overlapping fragments as described elsewhere.21 22 The resultant sequence data were compared with the revised Cambridge reference sequence (GenBank accession no. NC_001807).23 The published data on http://www.mtdb.igp.uu.se/ were used to determine the allelic frequency of the identified variants.

The 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation was also screened in 350 control individuals recruited from the same geographical region as the patients. To screen for the 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation, we synthesised a mismatched sense primer with 33 nt random sequence at the 5′ end: ggtgacactatagaatactcaagctatgcatcaTAACATGAAAACATTCTCCTGTGCA (nt 2311-2335), with an antisense primer GTGTTGGGTTGACAGTGAGGGTAAT(nt 2409-2433). The CC2331-2332GT mismatched primer, in combination with the 2336T>C mutation, created an Alw441 restriction enzyme site. The PCR segments (156 bp) around 2336T>C mutation were amplified with mtDNA as template and subsequently digested with the restriction enzyme Alw441. Digested PCR products and undigested PCR products were then analysed by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide to determine whether the 2336T>C mutation was present in these subjects.

To further examine the presence and degree of the 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation in different tissues, genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood, urine (epithelial-like cells detached from tubules), hair follicle and oral epithelium derived from the maternal members of this family, and a more sensitive experiment involving pyrosequencing technology was performed as described elsewhere.24

Phylogenetic analysis

For interspecific analysis of those variants identified, a total of 17 mitochondrial sequences were used as described elsewhere.21 The conservation index (CI) was calculated by comparing the human nucleotide variants with the other 16 species. The CI was then defined as the percentage of species harbouring the wild-type nucleotide at that position from the list of 17 different vertebrate species.

Structural analysis

The published secondary structures for the 16S rRNA were used to define the stem and loop structure.25 26 The secondary structure of the 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation was predicted by using the RnaViz program.27

Mutational analysis of nuclear genes

In order to determine the contribution of nuclear gene mutations in the pathogenesis of HCM in this family, four common known genes for HCM,9 including MYH7, MYBPC3, TNNT2 and TNNI3, were evaluated as described previously using PCR DNA sequencing.28–30 The sequence results were compared with the genomic sequence of MYH7 (GenBank accession no. NG_007884), MYBPC3 (GenBank accession no. NG_007667), TNNT2 (GenBank accession no. NC_000001.10) and TNNI3 (GenBank accession no. NC_000019.9).

Cell lines and culture conditions

Lymphoblastoid cell lines were immortalised by transformation with the Epstein–Barr virus as described elsewhere.31 Cell lines derived from affected individuals (II-1, II-3, III-1 and III-3) and controls with the same haplogroup M were grown in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone) and 0.11 mg/mL pyruvate. 143B was grown in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS.

Oxygen consumption measurements

The oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in intact cells was determined with Seahorse Bioscience XF96 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). All determinations were performed in triplicate. Normalisation to total protein content after an XF96-style experiment was conducted for proper interpretation of experimental results as described by Dranka et al.32

ATP measurements

The ATP level in cells was measured using the ATP Bioluminescence Assay kit HS II (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, samples of 1×106 cells were incubated for 2 h in 1 mL record solution (156 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 2 mM MgSO4, 1.25 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.35) with either 10 mM glucose (total ATP production) or 5 mM 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-DG) plus 5 mM pyruvate (oxidative ATP production). Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (100 mM Tris, 4 mM EDTA, pH7.75) and incubated for 5 min at 100°C. Samples were measured with BioTek Synergy H1 Hybrid Reader.

ROS measurements

ROS measurements were performed as described by Wang et al.33 Briefly, 2×106 cells were harvested and then suspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 10 μM of 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA). After incubation in culture chamber (37°C, 5% CO2) for 20 min, cells were washed, resuspended in PBS or PBS supplemented with 50 ug/mL H2O2 and incubated at room temperature for another 30 min. Finally, cells with or without stimulation by H2O2 were analysed, with an excitation at 488 nm and emission at 529 nm.

Electron microscopy

0.5–1 × 107 cells derived from four patients of this family and control individuals were collected and fixed for electron microscopic analysis as described elsewhere.34

Results

Clinical presentation

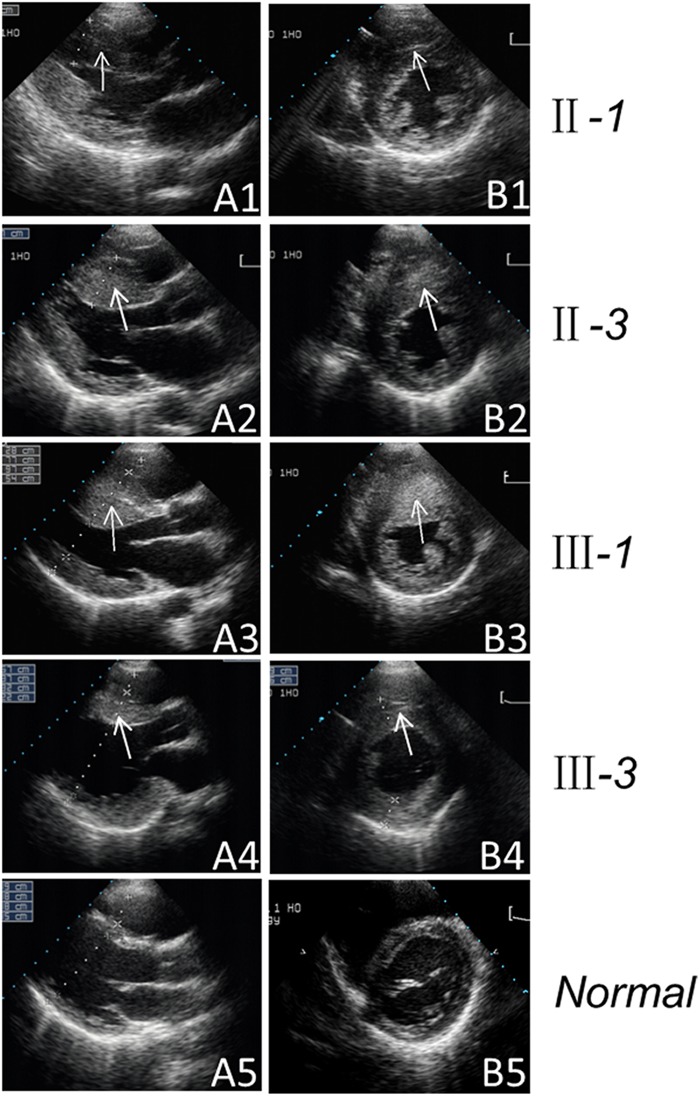

As shown in figure 1, all (4/4) of the maternal members are affected with HCM, in which maternally transmitted HCM is suggested. The clinical characteristics of the present 10 members (five men/five women) of this family are illustrated in table 1. The ECHOs of the individuals affected with HCM are shown in figure 2. All the maternal members (4/4) were affected with non-obstructive HCM and implanted permanent pacemaker due to complete atrioventicular block (IIIO AVB). As shown in table1, the MLVWT of the maternal members in this family ranged from 26.8 to 46.6 mm, with mean value of 37.4 mm, which is significantly thicker than the mean value of 9.03 mm in non-maternal members (p<0.02). In addition, there was no significant difference in the LPW between maternal and non-maternal members. However, the average IVS (33.8 mm) in maternal members was significantly higher than those in non-maternal members (with p<0.02), which finally resulted in asymmetric hypertrophy (IVS/LPW ≥ 1.3). Notably, complete penetrance of AVB was exhibited in this family, which finally led to permanent pacemaker implantation. Furthermore, no neuromuscular deficits were identified after a sufficient neuromuscular system examination by a specialist in neurology. The lactic acid in whole venous blood, the blood and urine routine test turned out to be normal.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical data for members of the Chinese pedigree with HCM

| Patient | Sex | Age (years) | BP (mm Hg) | ECHO | ECG rhythm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At testing | At onset | MLVWT (mm) | IVS (mm) | LPW (mm) | IVS/LPW | EF (%) | LAVI (mL/m2) | ||||

| Maternal members | |||||||||||

| II-1 | F | 59 | 45 | 125/68 | 26.8 | 23.1 | 7.2 | 3.21 | 57.5 | 28.2 | Pacing |

| II-3 | M | 49 | 37 | 115/78 | 38.7 | 36.9 | 12.6 | 2.93 | 74.6 | 43.41 | AF and Pacing |

| III-1 | M | 38 | 32 | 120/75 | 46.6 | 46.6 | 16.3 | 2.86 | 61.8 | 38.64 | AF and Pacing |

| III-3 | M | 32 | 29 | 110/70 | 37.4 | 28.7 | 7.2 | 3.99 | 43 | 39.95 | Pacing |

| Non-maternal members | |||||||||||

| II-2 | M | 57 | – | 155/85 | 10.2 | 10.2 | 8.7 | 1.17 | 72.4 | ND | Sinus |

| II-4 | F | 48 | – | 110/70 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 7.9 | 1.22 | 77.2 | ND | Sinus |

| III-2 | F | 30 | – | 100/70 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 8.0 | 1.19 | 76.6 | ND | Sinus |

| III-4 | F | 31 | – | 115/60 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 6.9 | 1.23 | 78.5 | ND | Sinus |

| IV-1 | F | 13 | – | 93/62 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 6.4 | 1.28 | 75 | ND | Sinus |

| IV-2 | M | 8 | – | 84/58 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 7.3 | 1.12 | 72 | ND | Sinus |

AF, atrial fibrillation; BP, blood pressure; ECHO, echocardiography; EF, ejection fraction; F, female; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; IVS, interventricular septum thickness; LPW, left posterior wall thickness; LAVI, left atrial volume index; M, male; MLVWT, maximum left ventricular wall thickness; ND, not done.

Figure 2.

Two-dimensional echocardiogram showing severe thickened left ventricular wall of the maternal members of the Chinese pedigree. Echocardiographic long-axis view (A1–A4) and short-axis view (B1–B4) reveal the thickened left ventricular walls of the maternal members (II-1, II-3, III-1 and III-3). The arrow indicates the thickened left ventricular walls. Apical four-chamber view (A5) and short-axis view (B5) reveal the normal heart of the control.

The proband's grandmother (I-2) died from gastric cancer at the age of 40. At present, his grandfather (I-1) is 88 years old and without any notable clinical abnormality. Furthermore, the non-maternal members of this family underwent the same clinical examinations as the maternal members, all having normal ECHO and ECG. Medical history, physical examination and laboratory tests showed that none of the participants, except the proband's father (II-2), showed any other clinical abnormalities. The proband's father (II-2) had hypertension (155/85 mm Hg).

In addition to the complete penetrance of AVB, left ventricular remodelling was also observed in the proband (III-3) (table 2). From October 2007 to April 2012, his LPW regressed about 68% at a rate of 3.3 mm/year. His IVS exhibited local thinning, while the maximum thickness of IVS remained stable. The left ventricular remodelling included LPW thinning and local thinning of IVS and resulted in the enlargement of the ventricular chamber. Accompanied by the LV wall thinning, this left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) increased by about 45% (from 50.4 mm in 2007 to 73 mm in 2012) at a rate of 4.52 mm/year, and the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) decreased substantially from 50% in February 2010 to 32% in April 2012, which suggested the progression of HCM to dilated cardiomyopathy in the proband. Due to congestive heart failure and ventricular systolic asynchrony, he received cardiac resynchronisation and implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy.

Table 2.

Left ventricular remodelling in the proband from 2007 to 2012

| October 2007 | March 2009 | February 2010 | December 2010 | April 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPW (mm) | 24.4 | 15.7 | 8.3 | 7.2 | 7.9 |

| IVS (mm) | 23.8 | 24.7 | 28.0 | 28.7 | 26.5 |

| IVS/ LPW | 0.98 | 1.57 | 3.37 | 3.99 | 3.35 |

| LVOTG (mm Hg) | 7.8 | 3.46 | 2.65 | 2.76 | 2.9 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 50.4 | 53.7 | 61.0 | 68.2 | 73.0 |

| LVEF (%) | 50 | 51.8 | 50 | 43 | 32.0 |

| LAVI (mL/m2) | Normal | ND | 41.4 | 39.95 | 56.3 |

IVS, interventricular septum thickness; LPW, left posterior wall thickness; LAVI, left atrial volume index; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVOTG, left ventricular outflow tract gradient; ND, not done.

Mitochondrial DNA analysis

The maternal transmission of HCM in this family suggested the mitochondrial involvement and led us to analyse the mtDNA of the maternal members. The sequencing of the entire mtDNA of the proband III-3 and II-1, II-3 and III-1 identified 40 nucleotide changes associated with haplogroup M7c1d (see online supplementary table S1). These variants in RNAs and polypeptides were further analysed by allelic frequency in control individuals according to the data published on http://www.mtdb.igp.uu.se/ and according to phylogenetic analysis encompassing 17 vertebrate species. The 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation was identified. The 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation, with high CI of 16/17, seems novel and highly conserved during evolution (see online supplementary figure S1). Allelic frequency analysis showed that the 2336T>C mutation was absent in the 2704 controls (http://www.genpat.uu.se/mtDB). In addition, the 2336T>C mutation was also absent in 350 age-matched and sex-matched Chinese control individuals with normal heart from the same region.

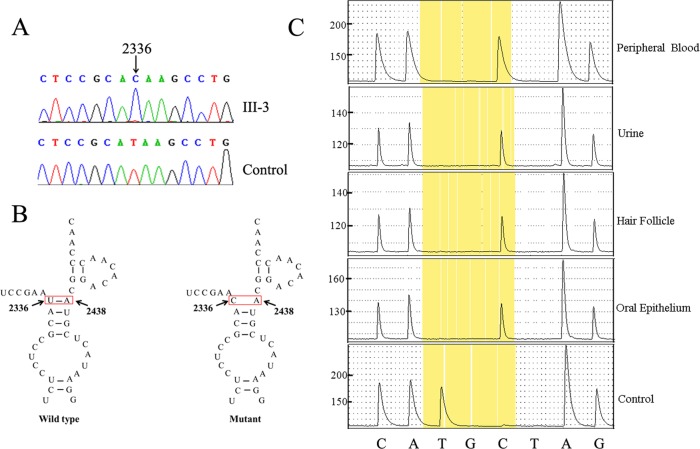

Partial sequence chromatograms of the 16S rRNA gene from the proband and control are shown in figure 3A. Pyrosequencing analysis indicated that the 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation was homoplasmic in blood, urine (epithelial-like cells detached from tubules), hair follicles and the oral epithelium of the proband (III-3) (figure 3C), as well as in II-1, II-3 and III-1 (see online supplementary figure S2). As shown in figure 3B, this mutation disturbs the 2336U-A2438 base pair in the stem–loop structure of 16S rRNA domain III, which has been proposed to be involved in the assembly of the mitochondrial ribosome.

Figure 3.

Identification and quantification of the 2336T>C mutation in the mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene. (A) Partial sequence chromatograms of the 16S rRNA gene from the proband (III-3) and a Chinese control individual. The arrows indicate the location of the base change at position 2336. (B) The location of the mitochondrial 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation. (C) Quantification of 2336T>C mutation by pyrosequencing in the different tissues of the proband (III-3). The boxes show the AQ value obtained for the allele.

Nuclear genes analysis

The PCR amplification and sequence analysis of DNA fragments spanning 39 exons of MYH7, 35 exons of MYBPC3, 17 exons of TNNT2 and 8 exons of TNNI3 and their flanking sequences were performed using DNA samples from four affected individuals of the Chinese family. However, we failed to identify the potential pathogenic mutations.

Mitochondrial dysfunction in the mutant lymphoblastoid cell lines

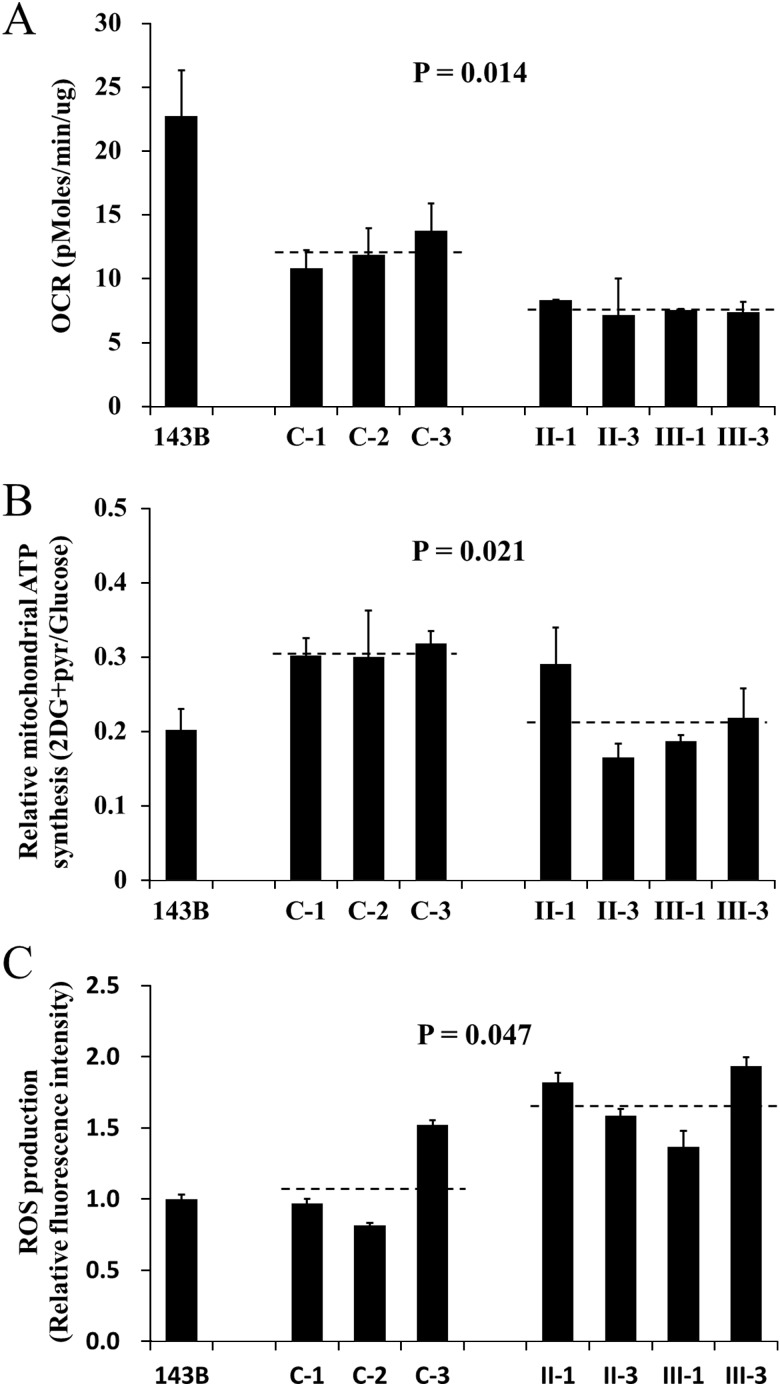

The respiration capacity of mutant cell lines carrying the 2336T>C mutation and control cell lines was measured by determining the OCR in intact cells with Seahorse XF96. As shown in figure 4A, the rate of total OCR in the mutant cell lines derived from affected individuals of this family (II-1, II-3, III-1 and III-3) had decreased significantly, with about a 37% reduction relative to controls with the same haplogroup M. Meanwhile, cells were cultured with glucose or under conditions that support only mitochondrial ATP synthesis (2-deoxy-d-glucose with pyruvate, 2DG+pyr). The mutant cell lines maintained similar levels of total ATP in glucose media with the controls. However, under oxidative conditions in the presence of 2DG+pyr, ATP levels were significantly reduced in mutant cell lines. As shown in figure 4B, the relative mitochondrial ATP production (2DG+pyr/glucose) is 30.7% in the controls while 21.5% in the mutant cell lines. Furthermore, abnormal ROS level was also present in mutant cell lines without stimulation of H2O2. As indicated in figure 4C, the ROS production in mutant cell lines is 1.68 relative to 143B cell, which is significantly higher than that in the controls (1.1). Therefore, it is suggested that the 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation results in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation defect.

Figure 4.

Determination of mitochondrial function. The 143B cell line was used as a control. The average of three determinations for each cell line is shown. (A) The oxygen consumption rate of the mutant lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from the maternal members (II-1, II-3, III-1 and III-3) of this Han Chinese family and three control individuals (C-1, C-2 and C-3) was determined with Seahorse Bioscience XF96 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). (B) The ATP level in mutant and control cell lines was measured with either 10 mM glucose (total ATP production) or 5 mM 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-DG) plus 5 mM pyruvate (oxidative ATP production), and the relative mitochondrial ATP synthesis was defined as the ratio of oxidative ATP production to total ATP production (2DG+pyr/glucose). (C) The rates of reactive oxidative species production in mutant and control cell lines were analysed. The relative fluorescence intensity without stimulation of H2O2 was calculated in relation to 143B.

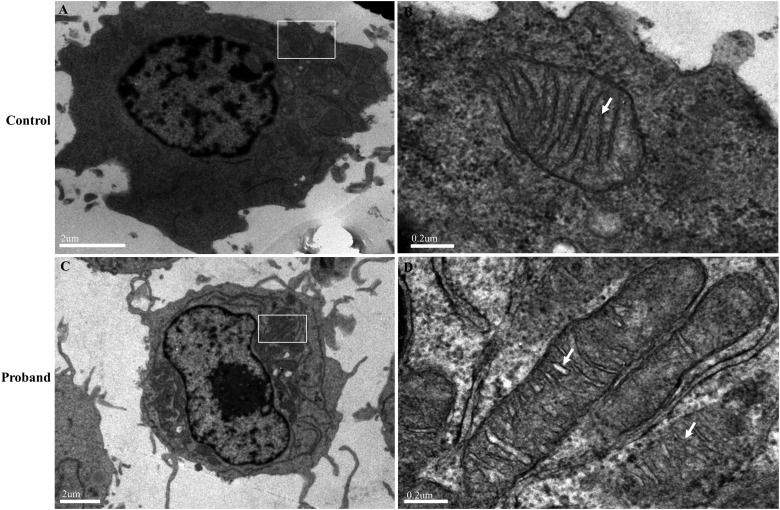

Electron microscopic analysis of mitochondria

Lymphoblastoid cells derived from affected individuals (II-1, II-3, III-1 and III-3) and control individuals were collected for electron microscopic analysis. And the mutant cells from four affected individuals demonstrated abnormal mitochondrial number and ultrastructure compared with the controls. The microscopic results of the proband (III-3) and one control individual (C-2) are shown in figure 5. The number of mitochondria in cells appeared greater for the proband (figure 5C) than for those in the control (figure 5A). Mitochondria with circular appearance and well-defined cristae were seen in the control (figure 5B), while the proband demonstrated extremely elongated mitochondria and mitochondria with disorganised and fragmented cristae (figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Electron microscopic analysis of mitochondria in lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from the proband (III-3) and a control individual (C-2). (A, B) Representative electron micrographs of cells from the control. Magnification: 6200× (A) or 39000× (B). (C, D) Representative electron micrographs of cells from the proband. Magnification: 3700× (A) or 39000× (B). The rectangles show the mitochondria in cells, and the arrows indicate the mitochondrial cristae.

Discussion

In the present study, we performed the clinical, genetic and molecular characterisation of a Han Chinese family with maternally inherited HCM. In the general HCM population, mostly with affected sarcomeric proteins, MLVWT shows a particularly wide range from 16.7 to 26.6 mm with mean LV wall thickness of 21.2 mm, and IVS/LPW from 1.7 to 2.8 with a mean value of 2.4.35 In our study, the MLVWT of the affected family ranges from 26.8 to 46.6 mm with a mean value of 37.4 mm, and IVS/LPW from 2.86 to 3.99 with a mean value of 3.25, which are significantly higher than those in the general HCM population. Meanwhile, the left ventricular outflow tract obstruction occurs in approximately 25% of the general HCM patients while rarely presenting in HCM associated with mtDNA mutations. This observation remains consistent with the results of our study. No neuromuscular deficits were identified after a sufficient neuromuscular system examination by a specialist in neurology, which might be due to the tissue-specific character of the mitochondrial disease.36 37 It is worth mentioning that the left ventricular remodelling that finally resulted in the progression of HCM to dilated cardiomyopathy was also observed in the proband.38 Furthermore, AVB, one of the conduction system defects, finally leading to the requirement of permanent pacemaker implantation, was represented with 100% penetrance in our study. This is a rare phenomenon in the general HCM population. AV block has an unknown or idiopathic cause, but familial clustering has been noted, and published pedigrees show an autosomal-dominant inheritance. Some individuals with AV conduction disease have a health history or family history of other forms of cardiovascular disease in the young, including cardiomyopathy. The genetic significance of these associations is not completely understood, but such findings are not unanticipated given the common origin of the specialised conduction system elements and the working myocardium. Therefore, the identification of mtDNA mutations that can cause these disorders could provide important information on their pathogenesis.

To identify putative deleterious mutations, 40 variants (2 novel and 38 known) identified in the proband III-3 and II-1, II-3 and III-1 were further evaluated according to the following three criteria39: (1) absence in the 2704 controls, (2) CI is >78% and (3) potential structural and functional alterations. On this basis, the novel 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation was identified. In contrast to tRNAs and protein encoding genes, mitochondrial rRNAs are relatively less involved in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases.40 41 This is the first report of a mitochondrial 16S rRNA mutation involved in HCM. HCM is mainly attributed to mutations of nuclear sarcomeric genes, in which MYH7, MYBPC3, TNNT2 and TNNI3 are the four most common known genes accounting for 35–50%, 20–25%, ∼20% and ∼5% of all HCM cases, respectively. In our study, the MYH7, MYBPC3, TNNT2 and TNNI3 were screened, and no potential pathogenic mutation was identified.

For further confirmation, the 2336T>C mutation was also screened for in 350 control individuals from the same region as the patients, and no such mutations were found. The 2336T>C mutation in different tissues including peripheral blood, urine (epithelial-like cells detached from tubules),42 hair follicle and oral epithelium of the proband, as well as in other affected individuals of this family, turned out to be homoplasmic. Peripheral blood and urine (epithelial-like cells detached from tubules) developed from mesoderm during differentiation and had the same origin as the cardiovascular system, indicating that the 2336T>C mutation might be homoplasmic in the myocardial cells.

The 2336T>C mutation disturbs the 2336U-A2438 base pair in the stem–loop structure of the 16S rRNA domain III, which is thought to interact with ribosomal proteins L19, L23 and L34 and play a role in the assembly of the mitochondrial ribosome.26 Galmiche et al43 reported that a mutation (P317R) in the large mitochondrial ribosomal protein MRPL3 altered ribosome assembly and caused a mitochondrial translation deficiency, resulting in an abnormal assembly of several complexes of the respiratory chain, and contributed to the pathogenesis of HCM. In our study, the 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation appears to be responsible for the reduced OCR of the mitochondrial respiration chain. Subsequently, these defects resulted in a reduction in mitochondrial ATP production and an increase in ROS production. The mitochondrial dysfunction may contribute to the pathogenesis of HCM in this family.

HCM is closely associated with the reduction of ATP yield or utilisation. The high-energy demand of the myocardium requires an ample and secure supply of ATP for its contractile and other metabolic activities, mainly derived from mitochondrial OXPHOS.44 The major finding of the present study is that myocardial contraction and relaxation reserves are related to mitochondrial function. Meanwhile, pathological mtDNA mutations have been associated with ultrastructurally abnormal mitochondria, and these defects have been shown to contribute to the pathogenesis of congestive heart failure complicating HCM.45 Furthermore, mitochondrial cristae shape has also been reported to determine respiratory chain supercomplexes assembly and respiratory efficiency.46 In our study, the microscopic observations of lymphoblastoid cells indicated that both the number and the size of mitochondria were increased in the patients than those in the controls, which support the hypothesis of energy compromise as a critical factor in the pathogenesis of HCM.47 In addition, abnormal mitochondrial cristae shape was also frequently present in the patients. These observations may be related to impaired mitochondrial function in cell lines carrying the 2336T>C mutation.

Therefore, the present results reveal that the 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation was one of the primary factors in the pathogenesis of HCM when combined with AVB. Meanwhile, other factors, including nuclear modifier genes, environmental factors and personal lifestyles, could not be excluded considering the heteroplasmic clinical presentations of the affected individuals in this family. However, limitations of our study should be pointed out. As the myocardial tissue was inaccessible, we used immortalised lymphoblastoid cell line derived from HCM patients as a research model, which could not provide direct evidence for the impact of the 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation on the function of myocardial cells. Currently, patient-specific-induced pluripotent stem cells and differentiated cells derived from them are attracting increasing attention to elucidate the mechanisms underlying HCM development,48 especially for cases with mitochondrial DNA mutations.49 50 Such efforts are in progress in our laboratory. In conclusion, this is the first report of mitochondrial 16S rRNA 2336T>C mutation and an association with maternally inherited HCM combined with AVB. Our findings provide a new insight into the pathogenesis of HCM.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Correction notice: This paper has been corrected since it appeared online. There were errors in the author affiliation list which have now been rectified in print.

We thank Professor Min-Xin Guan at Zhejiang University for mentoring and support; Dr Hui Liang at the First Affiliated Hospital, Medical School of Zhejiang University, for the neuromuscular system examination; Dr Immo E Scheffler at UC San Diego and Chris Wood of the College of Life Sciences, Zhejiang University, for discussion and writing supports; and Dr Guowei Fang at the Adicon Clinical Laboratories Inc. for pyrosequencing.

Contributors: QY, ZL and YS made substantial contributions to conception and design, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and analysis and interpretation of data. ZL, YS, XH, SL, BW, WW, SG, XZ, XW, QZ, YD and QY were responsible for acquisition of data. QY, ZL, YS, XH, SL, BW, WW, SG, XZ, XW, QZ and YD gave the final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (grant nos. 2012CB966804 and 2014CB943001), National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 30971599), Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-06-0526), Program for Science and Technology in Zhejiang Province (no. 2008C23028) and 151 Excellent Talents in Zhejiang Province (no. 06-2-008).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Maron BJ, Towbin JA, Thiene G, Antzelevitch C, Corrado D, Arnett D, Moss AJ, Seidman CE, Young JB. Contemporary definitions and classification of the cardiomyopathies: an American Heart Association Scientific Statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research and Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Groups; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation 2006;113:1807–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maron BJ, Shirani J, Poliac LC, Mathenge R, Roberts WC, Mueller FO. Sudden death in young competitive athletes: clinical, demographic, and pathological profiles. JAMA 1996;276:199–204 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E. Ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction: experimental observations and clinical implications. Circulation 1990;81:1161–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine HJ, Gaasch WH. Vasoactive drugs in chronic regurgitant lesions of the mitral and aortic valves. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;28:1083–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giannuzzi P, Tavazzi L, Temporelli PL, Corrà U, Imparato A, Gattone M, Giordano A, Sala L, Schweiger C, Malinverni C. Long-term physical training and left ventricular remodeling after anterior myocardial infarction: results of the exercise in anterior myocardial infarction (EAMI) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;22:1821–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spirito P, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, Epstein SE. Occurrence and significance of progressive left ventricular thinning and relative cavity dilatation in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 1987;60:123–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maron BJ, Epstein SE. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: pathophysiology and therapy. In: Braunwald E, ed. Heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 3rd edn (Update No.7) Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1989:157–68 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahl A, Saikia UN, Talwar KK. Familial conduction system disease associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2008;125:e44–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morita H, Rehm HL, Menesses A, McDonough B, Roberts AE, Kucherlapati R, Towbin JA, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Shared genetic causes of cardiac hypertrophy in children and adults. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1899–908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hattori Y, Takeoka M, Nakajima K, Ehara T, Koyama M. A heteroplasmic mitochondrial DNA 3310 mutation in the ND1 gene in a patient with type 2 diabetes, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and mental retardation. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2005;113:318–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song YR, Liu Z, Gu SL, Qian LJ, Yan QF. Advances in the molecular pathogenesis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. HEREDITAS 2011;33:549–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeviani M, Gellera C, Antozzi C, Rimoldi M, Morandi L, Villani F, Tiranti V, DiDonato S. Maternally inherited myopathy and cardiomyopathy: association with mutation in mitochondrial DNA tRNALeu(UUR). Lancet 1991;338:143–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Z, Song Y, Gu S, He X, Zhu X, Shen Y, Wu B, Wang W, Li S, Jiang P, Lu J, Huang W, Yan Q. Mitochondrial ND5 12338T>C variant is associated with maternally inherited hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a Chinese pedigree. Gene 2012;506:339–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charron P, Dubourg O, Desnos M, Isnard R, Hagege A, Millaire A, Carrier L, Bonne G, Tesson F, Richard P, Bouhour JB, Schwartz K, Komajda M. Diagnostic value of electrocardiography and echocardiography for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a genotyped adult population. Circulation 1997;96:214–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirota T, Kubo T, Kitaoka H, Hamada T, Baba Y, Hayato K, Okawa M, Yamasaki N, Matsumura Y, Yabe T, Doi YL. A novel cardiac myosin-binding protein C S297X mutation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiol 2010;56:59–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubourg O, Isnard R, Hagège A, Jondeau G, Desnos M, Sacrez A, Bouhour JB, Messner Pellenc P, Millaire A, Fetler L. Doppler echocardiography in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the French Cooperative Study. Echocardiography 1995;12:235–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiller NB, Shah PM, Crawford M, DeMaria A, Devereux R, Feigenbaum H, Gutgesell H, Reichek N, Sahn D, Schnittger I. Recommendations for quantitation of the left ventricle by two-dimensional echocardiography. American Society of Echocardiography Committee on Standards, Subcommittee on Quantitation of Two-Dimensional Echocardiograms. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1989;2:358–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJ. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2005;18:1440–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tani T, Yagi T, Kitai T, Kim K, Nakamura H, Konda T, Fujii Y, Kawai J, Kobori A, Ehara N, Kinoshita M, Kaji S, Yamamuro A, Morioka S, Kita T, Furukawa Y. Left atrial volume predicts adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2011;34:1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geske JB, Sorajja P, Ommen SR, Nishimura RA. Variability of left ventricular outflow tract gradient during cardiac catheterization in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2011;4:704–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu J, Li Z, Zhu Y, Yang A, Li R, Zheng J, Cai Q, Peng G, Zheng W, Tang X, Chen B, Chen J, Liao Z, Yang L, Li Y, You J, Ding Y, Yu H, Wang J, Sun D, Zhao J, Xue L, Wang J, Guan MX. Mitochondrial 12S rRNA variants in 1642 Han Chinese pediatric subjects with aminoglycoside-induced and nonsyndromic hearing loss. Mitochondrion 2010;10:380–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang X, Li R, Zheng J, Cai Q, Zhang T, Gong S, Zheng W, He X, Zhu Y, Xue L, Yang A, Yang L, Lu J, Guan MX. Maternally inherited hearing loss is associated with the novel mitochondrial tRNASer(UCN) 7505T>C mutation in a Han Chinese family. Mol Genet Metab 2010;100:57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrews RM, Kubacka I, Chinnery PF, Lightowlers RN, Turnbull DM, Howell N. Reanalysis and revision of the Cambridge reference sequence for human mitochondrial DNA. Nat Genet 1999;23:147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan X, Wang X, Wang Z, Sun S, Chen G, He Y, Mo JQ, Li R, Jiang P, Lin Q, Sun M, Li W, Bai Y, Zhang J, Zhu Y, Lu J, Yan Q, Li H, Guan MX. Maternally transmitted late-onset non-syndromic deafness is associated with the novel heteroplasmic T12201C mutation in the mitochondrial tRNAHis gene. J Med Genet 2011;48:682–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burk A, Douzery EJP, Springer MS. The secondary structure of mammalian mitochondrial 16S rRNA molecules: refinements based on a comparative phylogenetic approach. J Mammal Evol 2002;9:225–52 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mears JA, Sharma MR, Gutell RR, McCook AS, Richardson PE, Caulfield TR, Agrawal RK, Harvey SC. A structural model for the large subunit of the mammalian mitochondrial ribosome. J Mol Biol 2006;358:193–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Rijk P, De Wachter R. RnaViz. a program for the visualisation of RNA secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Res 1997;25:4679–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purushotham G, Madhumohan K, Anwaruddin M, Nagarajaram H, Hariram V, Narasimhan C, Bashyam MD. The MYH7 p.R787H mutation causes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in two unrelated families. Exp Clin Cardiol 2010;15:e1–4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bashyam MD, Purushotham G, Chaudhary AK, Rao KM, Acharya V, Mohammad TA, Nagarajaram HA, Hariram V, Narasimhan C. A low prevalence of MYH7/MYBPC3 mutations among familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients in India. Mol Cell Biochem 2012;360:373–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Otsuka H, Arimura T, Abe T, Kawai H, Aizawa Y, Kubo T, Kitaoka H, Nakamura H, Nakamura K, Okamoto H, Ichida F, Ayusawa M, Nunoda S, Isobe M, Matsuzaki M, Doi YL, Fukuda K, Sasaoka T, Izumi T, Ashizawa N, Kimura A. Prevalence and distribution of sarcomeric gene mutations in Japanese patients with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ J 2012;76:453–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller G, Lipman M. Release of infectious Epstein-Barr virus by transformed marmoset leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1973;70:190–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dranka BP, Benavides GA, Diers AR, Giordano S, Zelickson BR, Reily C, Zou L, Chatham JC, Hill BG, Zhang J, Landar A, Darley-Usmar VM. Assessing bioenergetic function in response to oxidative stress by metabolic profiling. Free Radic Biol Med 2011;51:1621–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang S, Li R, Fettermann A, Li Z, Qian Y, Liu Y, Wang X, Zhou A, Mo JQ, Yang L, Jiang P, Taschner A, Rossmanith W, Guan MX. Maternally inherited essential hypertension is associated with the novel 4263A> G mutation in the mitochondrial tRNAIle gene in a large Han Chinese family. Circ. Res 2011;108:862–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scorrano L, Ashiya M, Buttle K, Weiler S, Oakes SA, Mannella CA, Korsmeyer SJ. A distinct pathway remodels mitochondrial cristae and mobilizes cytochrome c during apoptosis. Dev Cell 2002:2:55–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gandjbakhch E, Gackowski A, du Montcel ST, Isnard R, Hamroun A, Richard P, Komajda M, Charron P. Early identification of mutation carriers in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy by combined echocardiography and tissue Doppler imaging. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1599–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guan MX, Yan Q, Li X, Bykhovskaya Y, Gallo-Teran J, Hajek P, Umeda N, Zhao H, Garrido G, Mengesha E, Suzuki T, del Castillo I, Peters JL, Li R, Qian Y, Wang X, Ballana E, Shohat M, Lu J, Estivill X, Watanabe K, Fischel-Ghodsian N. Mutation in TRMU related to transfer RNA modification modulates the phenotypic expression of the deafness-associated mitochondrial 12S ribosomal RNA mutations. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79:291–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen H, Zheng J, Xue L, Meng Y, Wang Y, Zheng B, Fang F, Shi S, Qiu Q, Jiang P, Lu Z, Mo JQ, Lu J, Guan MX. The 12S rRNA A1555G mutation in the mitochondrial haplogroup D5a is responsible for maternally inherited hypertension and hearing loss in two Chinese pedigrees. Eur J Hum Genet 2012;20:607–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bergman MR, Teerlink JR, Mahimkar R, Li L, Zhu BQ, Nguyen A, Dahi S, Karliner JS, Lovett DH. Cardiac matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression independently induces marked ventricular remodeling and systolic dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007;292:H1847–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruiz-Pesini E, Wallace DC. Evidence for adaptive selection acting on the tRNA and rRNA genes of human mitochondrial DNA. Hum Mutat 2006;143:357–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsieh RH, Li JY, Pang CY, Wei YH. A novel mutation in the mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene in a patient with MELAS syndrome, diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism and cardiomyopathy. J Biomed Sci 2001;8:328–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arbustini E, Diegoli M, Fasani R, Grasso M, Morbini P, Banchieri N, Bellini O, Dal Bello B, Pilotto A, Magrini G, Campana C, Fortina P, Gavazzi A, Narula J, Viganò M. Mitochondrial DNA mutations and mitochondrial abnormalities in dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Pathol 1998;153:1501–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou T, Benda C, Duzinger S, Huang Y, Li X, Li Y, Guo X, Cao G, Chen S, Hao L, Chan YC, Ng KM, Ho JC, Wieser M, Wu J, Redl H, Tse HF, Grillari J, Grillari-Voglauer R, Pei D, Esteban MA. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from urine. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;22:1221–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galmiche L, Serre V, Beinat M, Assouline Z, Lebre AS, Chretien D, Nietschke P, Benes V, Boddaert N, Sidi D, Brunelle F, Rio M, Munnich A, Rötig A. Exome sequencing identifies MRPL3 mutation in mitochondrial cardiomyopathy. Hum Mutat 2011;32:1225–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trounce I. Genetic control of oxidative phosphorylation and experimental models of defects. Hum Reprod 2000;15(Suppl 2):18–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arbustini E, Fasani R, Morbini P, Diegoli M, Grasso M, Dal Bello B, Marangoni E, Banfi P, Banchieri N, Bellini O, Comi G, Narula J, Campana C, Gavazzi A, Danesino C, Viganò M. Coexistence of mitochondrial DNA and beta myosin heavy chain mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with late congestive heart failure. Heart 1998;80:548–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cogliati S, Frezza C, Soriano ME, Varanita T, Quintana-Cabrera R, Corrado M, Cipolat S, Costa V, Casarin A, Gomes LC, Perales-Clemente E, Salviati L, Fernandez-Silva P, Enriquez JA, Scorrano L. Mitochondrial cristae shape determines respiratory chain supercomplexes assembly and respiratory efficiency. Cell 2013;155:160–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ashrafian H, Redwood C, Blair E, Watkins H. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a paradigm for myocardial energy depletion. Trends Genet 2003;19:263–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lan F, Lee AS, Liang P, Sanchez-Freire V, Nguyen PK, Wang L, Han L, Yen M, Wang Y, Sun N, Abilez OJ, Hu S, Ebert AD, Navarrete EG, Simmons CS, Wheeler M, Pruitt B, Lewis R, Yamaguchi Y, Ashley EA, Bers DM, Robbins RC, Longaker MT, Wu JC. Abnormal calcium handling properties underlie familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pathology in patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2013;12:101–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cherry AB, Gagne KE, McLoughlin EM, Baccei A, Gorman B, Hartung O, Miller JD, Zhang J, Zon RL, Ince TA, Neufeld EJ, Lerou PH, Fleming MD, Daley GQ, Agarwal S. Induced pluripotent stem cells with a mitochondrial DNA deletion. Stem Cells 2013;31:1287–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farrar GJ, Chadderton N, Kenna PF, Millington-Ward S. Mitochondrial disorders: aetiologies, models systems, and candidate therapies. Trends Genet 2013; 29:488–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.