Abstract

Polysubstance use in adolescence is a known precursor to chronic substance misuse. Identifying risk factors for polysubstance use is necessary to inform its prevention. The present study examined the association of elevated levels of multiple mental health symptoms with adolescents’ engagement in polysubstance use (past month use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana). In a US national sample of 8th, 10th, and 12th grade students from Monitoring the Future surveys, we estimated probability of polysubstance use associated with high levels of depressive symptoms, conduct problems, or both. Depressive symptoms and conduct problems, alone and particularly in combination, were associated with drastically elevated probability of polysubstance use. Adolescents with high levels of both depressive symptoms and conduct problems had the highest probability of polysubstance use. Among 8th and 10th graders, probability of polysubstance use associated with co-occurring mental health problems was significantly higher for girls than boys.

Keywords: substance use, co-existing problems, mental health

Using multiple substances in adolescence is a strong risk factor for adulthood addiction (Stenbacka, 2003). Polysubstance use additionally confers elevated risk for a range of adverse health behaviors and conditions, such as risky sexual behavior and suicidality (Connell, Gilreath, & Hansen, 2009; Wu, Pilowsky, & Schlenger, 2005). The role of mental health problems in use of individual substances has been well-characterized, but their role in polysubstance use is less clear. Investigations of the predictors of polysubstance use are particularly important in light of evidence that some common substances, including marijuana, are rarely used exclusively by adolescents (Jackson, Sher, & Schulenberg, 2005; Pape, Rossow, & Storvell, 2009). The present study examined increased probability of polysubstance use, here defined as using alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana in the last month, that is associated with conduct problems (CP) and depressive symptoms (DS) among a national sample of adolescents and tested for gender differences in these associations.

CP, which refer to externalizing symptoms such as rule-breaking and aggressive behavior, and DS, which refer to internalizing symptoms such as sadness and hopelessness, are each known to be associated with use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana individually during adolescence (Boys, Farrell, & Taylor, 2003; King, Iacono, & McGue, 2004; Mason & Windle, 2002; Repetto, Caldwell, & Zimmerman, 2005). Developmentally, CP and DS generally precede substance use (Kuperman, Schlosser, & Kramer, 2001; Mason, Hitchings, & McMahon, 2007). There is a robust positive relationship between CP and substance use during adolescence (Lansford et al., 2008; Maslowsky & Schulenberg, in press; Mason, Hitchings, & Spoth, 2008). Evidence regarding the relationship of DS to substance use is mixed, with various studies reporting positive, negative, and null associations (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Fite, Colder, & O’Connor, 2006; Sung, Erklani, & Angold, 2004).

CP and DS are two of the most commonly co-occurring symptom types during adolescence (Kovacs, Paulauskas, & Gatsonis, 1988; Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 2000). Lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder and conduct disorder for adolescents is approximately 11.7% and 7.6%, respectively (Merikangas et al., 2010). Sub-syndromal symptoms, which are more prevalent than full psychiatric diagnoses, are also associated with clinically significant impairment (Kessler & Waters, 1998; Myers, Brown, & Mott, 1995). In general, the presence of multiple risk factors increases the probability of negative developmental outcomes (Rutter & Sroufe, 2000; Sameroff, 2000). With regards to substance use, co-occurring mental health problems pose a particular risk (Ingoldsby, Kohl, McMahon, & Lengua, 2006; Marmorstein & Iacono, 2003). Consequently, the study of co-occurring mental health problems is necessary to advance understanding of their specific developmental sequelae as well as the more general implications of complex patterns of risk and protective factors on salient developmental outcomes such as substance use (Schulenberg & Zarrett, 2006).

Several previous studies assessing the effect of co-occurring CP and DS on adolescents’ use of alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana individually have found that having elevated levels of both CP and DS relates to higher risk of substance use than having one of these symptoms. Adolescents with co-occurring CP and DS symptoms are more likely to use alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana individually than adolescents with only one of these symptom types (Miller-Johnson et al., 1998) and are more likely to experience alcohol-related problems when they drink (Marmorstein, 2010). However, because no previous study has examined the association of CP and DS with polysubstance use, it is not clear whether co-occurring CP and DS also increase the probability of polysubstance use in adolescence, though their association with the individual substances provides reason to expect such an effect.

In addition to hypothesized associations of CP and DS with polysubstance use in the total adolescent population, there is reason to expect that these associations may vary by gender. Prevalence of mental health problems varies by gender during adolescence. Depressive disorders are more common among girls and conduct and behavioral disorders are more common among boys (Merikangas et al., 2010). Such gender differences in symptom prevalence are well documented, though the sources and consequences of these differences are less well understood (Rutter & Sroufe, 2000). Gender paradoxic theory notes that although girls are less likely to manifest disruptive behaviors such as CP, those behaviors tend to be more severe and more strongly associated with comorbid conditions such as substance use (Keenan & Loeber, 1994). We therefore examined gender interactions to test for differences in the association between mental health symptoms and polysubstance use in girls versus boys.

We focused on the three most commonly used substances during adolescence, alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana, whose contribution to significant morbidity, mortality, and risk for later addiction make them a serious threat to public health, given their relatively high prevalence among adolescents (Johnston et al., 2012). We defined polysubstance use as the use of all three of these substances during the past 30 days.

We hypothesized that high levels of CP and DS would relate to higher odds of polysubstance use, with highest odds of polysubstance use among those who endorsed high levels of both CP and DS. We also hypothesized that girls who manifested high levels of both CP and DS would have significantly higher odds of polysubstance use than boys with high levels of both symptoms, in accordance with the previously documented gender paradoxical effects in relation to CP.

Methods

Sample and procedure

Participants were from annual, nationally representative, cross-sectional Monitoring the Future (MTF) surveys (Johnston et al., 2012). MTF tracks behaviors and attitudes of American youth, with a focus on substance use and its predictors. Each year, nationally representative samples of 8th, 10th, and 12th grade students, approximately 15,000 students per grade, are surveyed. The sample for the current study consisted of students who completed survey forms containing both mental health symptoms and substance use items, a random one-third of 8th and 10th graders and a random one-sixth of 12th graders surveyed (N = 198,659). The sample’s gender and racial/ethnic composition reflected that of the U.S. adolescent population: 51% female, 64% White, 13% Black, 11% Hispanic, and 11% other race. Data for 8th and 10th grade students were from 1991-2009; data for 12th grade students were from 1991-1996 (due to item availability; mental health and substance use items were not administered on the same survey form in subsequent years). Preliminary analyses testing for cohort differences in the relationships between mental health symptoms and substance use revealed no systematic differences; therefore, data from all cohorts were combined within each grade.

Measures

Conduct problems (CP) were measured via seven items on a scale of 1 = “Never” to 5 = “5 or more times” (α = .76.). Each item began with the stem, “In the past twelve months, how often have you…”. The seven items were: “taken something not belonging to you worth over $50?”, “taken something not belonging to you worth under $50?”, “taken part in a fight where a group of your friends were against another group?”, “gone into some house or building when you weren’t supposed to be there?”, “damaged school property on purpose?”, “gotten into a serious fight at work or school”, and “hurt someone badly enough to need bandages or a doctor?”.

Depressive symptoms (DS) were measured via four items on a scale of 1 = “Disagree” to 5 = “Agree”, (α = .72). Participants were asked, “How much do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements?” The four items were: “Life often seems meaningless”, “The future often seems hopeless”, “It feels good to be alive”, and “I enjoy life as much as anyone”. The latter two items were reverse coded. The items are similar to those on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) and have been used in previous studies (Merline, Jager, & Schulenberg, 2008; Schulenberg & Zarrett, 2006).

Alcohol use was measured via a single standard item, “On how many occasions have you drank alcohol, more than just a few sips, in the past 30 days?” on a scale of 1 = “0 occasions” to 7 = “40+ occasions”.

Marijuana use was measured via a single standard item, “On how many occasions have you used marijuana in the past 30 days?” using the same scale as alcohol use.

Cigarette use was measured via a single standard item, “How frequently have you smoked cigarettes during the past 30 days?” on a scale of 1= “Not at all” to 7 = “2 packs or more per day”.

Mental health symptom and substance use categories

Analyses focused on categories of young people to highlight relations among the constructs for adolescents at the more problematic end of the mental health and substance use continua, as well as to facilitate interpretation with multiple constructs. Substance use variables were coded to indicate whether the respondent had used each substance in the past 30 days, with 0 indicating no use and 1 indicating any use. The CP and DS scales were categorized; CP scores above 2 (out of 5) and DS scores above 3 (out of 5) were used as cutoffs for high scores, placing approximately 8-9% of students into the “high” category for each symptom; the remaining students were placed in the low category (Table 1). These cutoffs were specifically chosen a priori, based on psychiatric epidemiological estimates that approximately 12% of adolescents manifest clinically significant DS and approximately 8% develop significant CP (Merikangas et al., 2010). We constructed the cutoffs such that approximately 8-9% of our sample was categorized as high on DS or CP, approximating as closely as possible in these data the national epidemiological estimates of the number of youth who experience clinically significant symptoms.

Table 1.

Symptom and Substance Use Category Membership by Grade (N = 195,744)

| 8th grade (n = 90,968) |

10th grade (n = 93,899) |

12th grade (n = 13,792) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health Symptom Category (% of students) | |||

| Neither Symptom | 83.0 | 82.3 | 76.8 |

| Conduct Problems Only (CP) | 7.3 | 7.7 | 7.3 |

| Depressive Symptoms Only (DS) | 7.3 | 7.7 | 12.9 |

| Conduct Problems and Depressive Symptoms (CP+DS) | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.9 |

| Substance Use Category (% of students) | |||

| No Use* | 73.8 | 56.6 | 42.3 |

| Alcohol Only* | 10.9 | 17.2 | 21.6 |

| Alcohol and Cigarettes | 4.8 | 7.1 | 13.0 |

| Alcohol, Cigarettes, and Marijuana* | 3.9 | 8.1 | 12.2 |

| Cigarettes Only | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.6 |

| Alcohol and Marijuana | 1.5 | 4.4 | 4.6 |

| Marijuana Only | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.8 |

| Cigarettes and Marijuana | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.0 |

Indicates categories included in logistic regression analyses.

High/low DS and high/low CP were crossed to form four mutually exclusive symptom categories: Neither (high on neither DS nor CP), DS only (high on DS but not CP), CP only (high on CP but not DS), or CP+DS (high on both). The three dichotomous substance use variables (alcohol use, cigarette use, and marijuana use) were crossed to form eight mutually exclusive categories of combinations of substances use during the past 30 days (Table 1). Those in the polysubstance use category (Alcohol, Cigarettes, and Marijuana) were compared to those in the Alcohol Only and No Substance Use categories. We were interested specifically in probability of polysubstance use compared to using only alcohol, an indicator of relatively normative adolescent substance use, and to abstaining from substance use. Therefore, students in the remaining categories of substance use were not included in further analyses.

Analyses

Logistic regression analyses were completed using Mplus version 6.1 with full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to account for missing data (Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2010). Stratum and cluster variables were used to account for the nested structure of the data (students within schools within sampling area); sampling weights adjusted for differential sampling probability. All analyses were performed separately within each grade. Because of the large sample size, significance was tested using α = .001 to be conservative regarding significant findings. All analyses controlled for race/ethnicity and parental education (indicator of socioeconomic status) in order to adjust for any association of mental health symptoms with polysubstance use that may be attributable to these factors. Testing for differences in the relationship of mental health and substance use within strata of parental education or racial/ethnic categories was beyond the scope of the current paper.

Mental health symptom categories were tested as predictors of odds of membership in each substance use category, with the Neither Symptom group serving as the reference category. The reference categories for polysubstance use were No Use and Alcohol Only. These categories were chosen as reference categories because they were the two most common substance use categories in our sample and therefore represent the most normative patterns of substance use. Two outcome contrasts were tested: Alcohol, Cigarettes, and Marijuana versus Alcohol Only; and Alcohol, Cigarettes, and Marijuana versus No Use.

Results

Associations of mental health symptoms with polysubstance use

Results of the logistic regressions are presented in Table 2. As hypothesized, CP+DS was related to higher odds of polysubstance use (Alcohol, Cigarettes, and Marijuana) versus single substance use (Alcohol Only) or No Use. In other words, students who had high levels of one or both mental health symptoms had dramatically higher odds of using multiple substances than using only alcohol or using no substances compared to students who did not have high levels of either symptom. For example, the odds of using Alcohol, Cigarettes, and Marijuana (compared to using no substance) were about 39 times higher among 8th grade students who had high levels of CP and DS than among those who did not have high levels of either symptom. Predicted probabilities of substance use category membership are presented in Table 3. Students with high levels of CP, DS, or CP+DS, compared to students who did not have high levels of either symptom, had consistently higher predicted probabilities of polysubstance use versus No Use or Alcohol Only. For example, 8th graders with high CP+DS had a predicted probability of polysubstance use versus no substance use of .51; the predicted probability of the same outcome for their peers in the Neither Symptom category was .02.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression: Odds of Polysubstance Use by Mental Health Symptom Category

| Alcohol, Cigarettes, and Marijuana v. No Use |

Alcohol, Cigarettes, and Marijuana v. Alcohol Only |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| 8th grade | n = 70,776 | n = 13,454 | ||

| Neither Symptom (Reference) | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| Conduct Problems Only (CP) | 21.3a | 19.2 - 23.6 | 5.2 | 4.6 - 5.8 |

| Depressive Symptoms Only (DS) | 3.6a | 3.2 - 4.1 | 2.1 | 1.8 - 2.5 |

| Conduct Problems and Depressive Symptoms (CP+DS) | 38.8a | 33.5 - 45.0 | 9.3 | 7.9 - 11.0 |

| 10th grade | n = 60,934 | n = 23,556 | ||

| Neither Symptom (Reference) | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| Conduct Problems Only (CP) | 14.0 | 12.8 - 15.3 | 4.2 | 3.8 - 4.6 |

| Depressive Symptoms Only (DS) | 2.4 | 2.2 - 2.6 | 1.9 | 1.7 - 2.1 |

| Conduct Problems and Depressive Symptoms (CP+DS) | 18.9 | 16.2 - 21.9 | 6.9 | 5.9 - 8.2 |

| 12th grade | n = 7,471 | n = 4,599 | ||

| Neither Symptom (Reference) | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| Conduct Problems Only (CP) | 11.6 | 9.0 - 15.1 | 4.3 | 3.4 - 5.4 |

| Depressive Symptoms Only (DS) | 2.2 | 1.7 - 2.7 | 2.2 | 1.8 - 2.8 |

| Conduct Problems and Depressive Symptoms (CP+DS) | 18.0 | 10.6 - 30.4 | 13.3 | 7.9 - 22.5 |

Note: All coefficients are significant, p < .001. All analyses controlled for race/ethnicity and parental education.

8th grade students differed significantly from both 10th and 12th grade students

Table 3.

Predicted Probabilities of Polysubstance Use by Mental Health Symptom Category

| Predicted Probability of Alcohol, Cigarette and Marijuana Use (versus No Use) |

Predicted Probability of Alcohol, Cigarette and Marijuana Use (versus Alcohol Use Only) |

|

|---|---|---|

| 8th grade | n = 70,776 | n = 13,454 |

| Neither Symptom (Reference) | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| Conduct Problems Only (CP) | 0.35 | 0.50 |

| Depressive Symptoms Only (DS) | 0.08 | 0.28 |

| Conduct Problems and Depressive Symptoms (CP+DS) | 0.51 | 0.64 |

| 10th grade | n = 60,934 | n = 23,556 |

| Neither Symptom (Reference) | 0.08 | 0.24 |

| Conduct Problems Only (CP) | 0.54 | 0.58 |

| Depressive Symptoms Only (DS) | 0.18 | 0.39 |

| Conduct Problems and Depressive Symptoms (CP+DS) | 0.63 | 0.67 |

| 12th grade | n = 7,471 | n = 4,599 |

| Neither Symptom (Reference) | 0.16 | 0.29 |

| Conduct Problems Only (CP) | 0.66 | 0.59 |

| Depressive Symptoms Only (DS) | 0.27 | 0.44 |

| Conduct Problems and Depressive Symptoms (CP+DS) | 0.75 | 0.75 |

Note: All analyses controlled for race/ethnicity and parental education.

In order to ensure that the associations between mental health symptom categories and polysubstance use were not driven solely by associations of either cigarette or marijuana use with mental health symptoms, we conducted additional analyses in which we compared the polysubstance use group to the cigarette use only and marijuana use only groups. In these analyses CP, DS, and CP+DS were each associated with higher odds of polysubstance use than with marijuana or cigarette use only, indicating that the effects seen in the analyses of polysubstance use (Alcohol, Cigarettes, and Marijuana group) versus Alcohol Only or versus No Use were not attributable solely to marijuana or cigarette use.

In addition, although use of other illicit drugs besides marijuana was not a focus of the current investigation, we conducted supplementary analyses to ensure that the association of mental health symptoms with polysubstance use was not driven by other illicit drug use, because users of other illicit drugs were overrepresented in the polysubstance use group. Specifically, we reran the analyses predicting odds of polysubstance use versus no use and versus alcohol use only while excluding those polysubstance users who also reported use of illicit drugs other than marijuana (45% of that group). While the odds ratios reflecting the association of CP, DS, and CP+DS to polysubstance use were reduced somewhat when the other illicit drug users were excluded, all remained significant, and the pattern of results did not change in any way. We therefore chose to retain these students in the analysis.

Finally, sensitivity analyses were conducted with regard to cutoff scores for mental health symptom categories in order to ensure that the current results were not the spurious result of our particularly chosen cutoff scores for high levels of mental health symptoms. Two sets of lower cutoff levels for the high mental health symptoms group were used, such that approximately 12% or 20% of the sample was categorized as high on DS or CP. Logistic regressions in which mental health symptom categories predicted substance use category membership were rerun with categorizations. Predictably, the odds ratios regarding the association of DS, CP, or DS+CP to polysubstance use versus alcohol or no use when the symptom cutoff scores were lowered were slightly smaller than those presented in the current report. Notably, the odds ratios remained large (ranging from 2.0 - 18.0), and the pattern of findings did not change, offering additional assurance that the findings presented here are not a spurious result of the chosen cutoffs. Given these results, we chose to retain the original, a priori cutoffs.

Gender and age differences in associations of mental health symptoms with polysubstance use

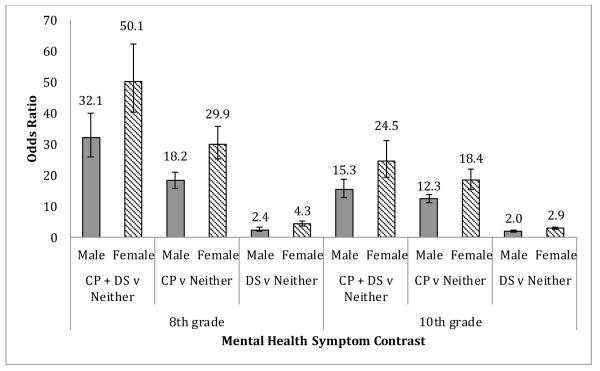

We tested the interaction of gender with symptom categories to determine whether mental health symptom categories differentially related to substance use among girls and boys. A systematic pattern of interactions was found. In 8th and 10th grades, the odds ratios for polysubstance use among those with high levels of CP, DS, and CP+DS were significantly stronger for girls than boys (Figure 1); there were no significant gender interactions among 12th grade students. For example, among 8th grade students with high CP+DS versus those with low levels of both symptoms, girls had an odds ratio of 50.1 (95% CI: 40.4-62.1) and boys had an odds ratio of 32.1 (95% CI: 25.9-39.9). In other words, the odds of polysubstance use versus no substance use for girls with high CP+DS were 50 times greater than the odds of polysubstance use versus no substance use for girls who did not have high levels of either symptom. For boys, this odds ratio was 32.1, still a very large increase in odds of polysubstance use, but not as high as that of girls. Girls with high levels of CP only or DS only also had higher probability of polysubstance use than boys with similarly high symptom levels.

Figure 1.

Gender differences in odds of polysubstance use. 8th and 10th grade girls (versus boys) had higher odds of polysubstance use (use of alcohol, marijuana, and cigarettes in the past 30 days) associated with elevated levels of conduct problems (CP), depressive symptoms (DS), or both (CP + DS).

Tests for grade-level differences in the association of the mental health categories to polysubstance use revealed that the odds of polysubstance use versus no use associated with CP, DS, and CP+DS were significantly larger among 8th graders versus 10th and 12th graders, though all three categories of mental health symptoms were significantly associated with polysubstance use in all three grades.

Discussion

In a national sample of 8th, 10th, and 12th grade adolescents, we examined the association of conduct problems (CP), depressive symptoms (DS), and their co-occurrence (CP+DS) to polysubstance use (reporting use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana in the past month). Within this national sample, we identified students who were among the top decile of their peers in levels of DS, CP, or both. We estimated the odds of polysubstance use versus using alcohol only or using no substances by youth with high levels of DS, CP, or both versus those without high levels of these symptoms.

Co-occurring mental health symptoms indicate highest probability of polysubstance use

Multiple risk factors, particularly co-occuring mental health problems (Ingoldsby, Kohl, McMahon, & Lengua, 2006; Marmorstein & Iacono, 2003), are known to set the stage for poor developmental outcomes (Rutter & Sroufe, 2000; Sameroff, 2000). In the present study, as hypothesized, high levels of CP, DS, and particularly CP+DS, related to increased probability of polysubstance use relative to abstaining from substance use. Individually and when co-occurring, CP and DS were also associated with increased probability of polysubstance use versus using alcohol only, indicating that these mental health problems tend to be more strongly associated with problematic patterns of substance use such as substance use than with the more normative substance use that using alcohol only may represent. Adolescents with high levels of CP+DS had the highest probability of using alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana together; the predicted probability of polysubstance use in this group ranged from .51 in 8th graders to .75 in 12th graders. These adolescents had greater probability of polysubstance use than their peers who reported high levels of only one symptom category, again highlighting the specific increase in risk for polysubstance use associated with co-occurring CP+DS. Although use of illicit drugs other than marijuana was not a focus of the current study, our analyses revealed that members of the polysubstance use group were also more likely to use other illicit drugs, giving some indication that CP+DS may also increase probability of other illicit drug use.

These results are consistent with other recent studies demonstrating stronger associations of mental health problems to polysubstance use than to single substance use. Results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions showed that Major Depressive Disorder was more strongly associated with polysubstance use than single substance use among adults (Agrawal, Lynskey, & Madden, 2006). Among adolescents, conduct problems have been shown to be more strongly associated with using alcohol and marijuana together than alcohol use alone (Shillington & Clapp, 2002).

The present study, with its national sample, extends this literature in several respects. While the bulk of previous studies have examined use of alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana individually, this study considers their concurrent use within a 30-day period, a more severe pattern of substance use. In doing so, it highlights the particularly high probability of polysubstance use among adolescents with high levels of both CP and DS. It also offers additional nuance in the understanding of complex interactions among multiple substance use risk factors and outcomes (Schulenberg & Zarrett, 2006), including clarifying the role of depressive symptoms in polysubstance use and revealing the higher probability of polysubstance use in girls versus boys who have elevated levels of mental health problems.

Role of depressive symptoms in polysubstance use

While the positive association of conduct problems to substance use has been clearly demonstrated by many past studies, previous research has yielded mixed results regarding whether DS are associated with substance use during adolescence (e.g. Fite, Colder, & O’Connor, 2006; Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999). In the current study, high levels of DS were positively associated with higher probability of polysubstance use in 8th, 10th, and 12th grades. Notably, although high levels of DS alone were related to increased probability of polysubstance use, CP was more strongly related to polysubstance use, and the highest probability was associated with those endorsing high levels of CP+DS. These results indicate that the primary association of DS to substance use during adolescence may be in its co-occurrence with CP, where it seems to have a potentiating effect on CP; youth who have high levels of DS in addition to CP have greater probability of polysubstance use than those who with CP only.

Higher probability of polysubstance use among female adolescents

We hypothesized that probability of polysubstance use would be higher among girls than boys who had CP+DS. This hypothesis was supported; high levels of mental health symptoms were related to greater probability of polysubstance use versus no substance use in 8th and 10th grades girls than boys. This result is consistent with the gender paradoxic effects noted in previous work (Keenan & Loeber, 1994), which note that CP are less common among girls but are associated with more severe comorbidities among those girls who do develop high levels of CP. Thus, the relatively small sub-group of adolescent girls who are among the highest decile of their peers in both CP and DS have a very high probability of polysubstance use. This is not to say that adolescent boys with elevated levels of mental health symptoms are not at risk for polysubstance use, and in fact, any elevated level of mental health symptoms is a strong signal for risk of polysubstance use during adolescence. Nonetheless, our findings regarding girls are of special theoretical interest and extend the literature regarding tighter comorbidity of mental health and substance use difficulties among adolescent girls.

Limitations

This study has several important strengths, including the use of a national sample of adolescents to identify those youth with the highest levels of CP and DS, using epidemiological estimates of the prevalence of clinically significant levels of these symptoms to guide our classifications. This allowed us to consider the probability of polysubstance use among those with elevated levels of CP and DS individually as well as in combination. A second important strength was that we examined alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette use together, adding to the existing literature that has examined mental health in relation to these substances individually but not in combination. Studying concurrent use of multiple substances is arguably more reflective of the ways in which adolescents actually use these substances, more often together than individually (Pape et al., 2009).

There are also several notable limitations. Due to the cross-sectional data, only contemporaneous associations between mental health and polysubstance use were examined. Additional longitudinal work is warranted to examine the causal nature of the relationship of early adolescent mental health problems to polysubstance use throughout adolescence as well as developmental changes in the strength and nature of these associations. Second, all data are self-reports, and although self-report measures of substance use and related behaviors are generally sufficiently reliable and valid (O’Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 1983), the findings are subject to the limitations of self-report. Finally, the measures of CP and DS available in these national survey data were brief (seven items for CP and four items for DS). Although more established measures of mental health problems would be preferable, such brief measures are a necessity in large-scale survey research. Additional studies assessing mental health problems in greater depth and examining their association with polysubstance use would provide an ideal complement to the national-level results provided here.

Conclusion

In sum, the current study makes two contributions to the extant literature. It demonstrates in a national sample the heightened probability of polysubstance use associated with co-occurring CP and DS. Those adolescents who have high levels of both symptoms have a much greater likelihood of engaging in polysubstance use not only in comparison to peers with low or no symptoms of mental health problems but also in comparison to their peers who have high levels of CP or DS only. Additionally, youth with high levels of CP+DS are more likely to engage in polysubstance use than to use only alcohol, indicating that co-occurring mental health symptoms may relate specifically to polysubstance use by adolescents. This study also revealed that these associations were particularly pronounced among 8th and 10th grade girls, whose probability of polysubstance use was greater than that of boys reporting similar levels of mental health symptoms.

These results suggest that future studies of adolescent polysubstance use should attend to both CP and DS as risk factors. Additional studies are needed to further examine why the likelihood of polysubstance use is particularly high for young girls with elevated levels of depressive symptoms and conduct problems. Practically, targeting prevention efforts to adolescents who experience CP+DS represents a potentially high-yield strategy for preventing or mitigating adolescent polysubstance use.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse: F31 DA293352 (Maslowsky) and R01 DA01411 (Schulenberg, Kloska, & O’Malley).

References

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Heath AC. A latent class analysis of illicit drug abuse/dependence: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Addiction. 2007;102(1):94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01630.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;1:57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boys A, Farrell M, Taylor C, Marsden J, Goodman R, Brugha T, Meltzer H. Psychiatric morbidity and substance use in young people aged 13-15 years: Results from the Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;182(6):509–517. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.6.509. doi:10.1192/bjp.182.6.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: III. Prediction to young-adult adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11(1):59–84. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. doi:10.1017/S0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Gilreath TD, Hansen NB. A multiprocess latent class analysis of the co-occurrence of substance use and sexual risk behavior among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(6):943–951. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fite PJ, Colder CR, O’Connor RM. Childhood behavior problems and peer selection and socialization: risk for adolescent alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(8):1454–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.015. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM, Kohl GO, McMahon RJ, Lengua L. Conduct problems, depressive symptomatology and their co-occurring presentation in childhood as predictors of adjustment in early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34(5):603–621. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9044-9. doi:10.1007/s10802-006-9044-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Schulenberg JE. Conjoint developmental trajectories of young adult substance use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32(5):723–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00643.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00643.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2011. Volume I: Secondary school students. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2012. p. 760. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Walters EE. Epidemiology of DSM-III-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depression and Anxiety. 1998;7(1):3–14. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1998)7:1<3::aid-da2>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99(12):1548–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Paulauskas S, Gatsonis C, Richards C. Depressive disorders in childhood: III. A longitudinal study of comorbidity with and risk for conduct disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1988;15(3):205–217. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90018-3. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(88)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperman S, Schlosser SS, Kramer JR, Bucholz K, Hesselbrock V, Reich T, Reich W. Developmental sequence from disruptive behavior diagnosis to adolescent alcohol dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(12):2022–2026. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2022. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Erath S, Yu T, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Bates JE. The developmental course of illicit substance use from age 12 to 22: Links with depressive, anxiety, and behavior disorders at age 18. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49(8):877–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01915.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01915.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn P, Rohde P, Seeley J. Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder in a community sample: Predictors of recurrence in young adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1584–1591. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Keenan K. Interaction between conduct disorder and its comorbid conditions: Effects of age and gender. Clinical Psychology Review. 1994;14(6):497–523. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(94)90015-9. [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR, Iacono WG. Major depression and conduct disorder in a twin sample: Gender, functioning, and risk for future psychopathology. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(2):225–233. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200302000-00017. doi:10.1097/00004583-200302000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowsky J, Schulenberg J. Interaction matters: Quantifying conduct problem by depressive symptoms interaction and its association with adolescent alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use in a national sample. Development and Psychopathology. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000357. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason WA, Hitchings JE, McMahon RJ, Spoth RL. A test of three alternative hypotheses regarding the effects of early delinquency on adolescent psychosocial functioning and substance involvement. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35(5):831–843. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9130-7. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W, Hitchings JE, Spoth RL. The interaction of conduct problems and depressed mood in relation to adolescent substance involvement and peer substance use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96(3):233–248. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.012. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W, Windle M. Reciprocal relations between adolescent substance use and delinquency: A longitudinal latent variable analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:63–76. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merline A, Jager J, Schulenberg JE. Adolescent risk factors for adult alcohol use and abuse: Stability and change of predictive value across early and middle adulthood. Addiction. 2008;103(Suppl1):84–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02178.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Johnson S, Lochman JE, Coie JD, Terry R, Hyman C. Comorbidity of conduct and depressive problems at sixth grade: substance use outcomes across adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26(3):221–232. doi: 10.1023/a:1022676302865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth Edition Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley P, Bachman J, Johnston L. Reliability and consistency in self-reports of drug use. International Journal of the Addictions. 1983;18:805–824. doi: 10.3109/10826088309033049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape H, Rossow I, Storvoll EE. Under double influence: assessment of simultaneous alcohol and cannabis use in general youth populations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;101(1-2):69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.11.002. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Repetto PB, Caldwell CH, Zimmerman MA. A longitudinal study of the relationship between depressive symptoms and cigarette use among African American adolescents. Health Psychology. 2005;24(2):209–219. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.209. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Sroufe LA. Developmental psychopathology: Concepts and challenges. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12(3):265–296. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003023. doi:10.1017/S0954579400003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A. Developmental systems and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:297–312. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Zarrett NR. Mental health during emerging adulthood: Continuity and discontinuity in courses, causes, and functions. In: Arnett JJ, Tanner JL, editors. Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. 2006. pp. 135–172. [Google Scholar]

- Shillington A, Clapp J. Beer and bongs: Differential problems experienced by older adolescents using alcohol only compared to combined alcohol and marijuana use. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:379–397. doi: 10.1081/ada-120002980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenbacka M. Problematic alcohol and cannabis use in adolescence--risk of serious adult substance abuse? Drug & Alcohol Review. 2003;22(3):277. doi: 10.1080/0959523031000154418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung M, Erkanli A, Angold A, Costello EJ. Effects of age at first substance use and psychiatric comorbidity on the development of substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;75(3):287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.013. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L-T, Pilowsky DJ, Schlenger WE. High prevalence of substance use disorders among adolescents who use marijuana and inhalants. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;78(1):23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.025. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]