Summary

Most human tissues express low levels of telomerase and undergo telomere shortening and eventual senescence; the resulting limitation on tissue renewal can lead to a wide range of age-dependent pathophysiologies. Increasing evidence indicates that the decline in cell division capacity in cells that lack telomerase can be influenced by numerous genetic factors. Here, we use telomerase-defective strains of budding yeast to probe whether replicative senescence can be attenuated or accelerated by defects in factors previously implicated in handling of DNA termini. We show that the MRX (Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2) complex, as well as negative (Rif2) and positive (Tel1) regulators of this complex, comprise a single pathway that promotes replicative senescence, in a manner that recapitulates how these proteins modulate resection of DNA ends. In contrast, the Rad51 recombinase, which acts downstream of the MRX complex in double-strand break (DSB) repair, regulates replicative senescence through a separate pathway operating in opposition to the MRX-Tel1-Rif2 pathway. Moreover, defects in several additional proteins implicated in DSB repair (Rif1 and Sae2) confer only transient effects during early or late stages of replicative senescence, respectively, further suggesting that a simple analogy between DSBs and eroding telomeres is incomplete. These results indicate that the replicative capacity of telomerase-defective yeast is controlled by a network comprised of multiple pathways. It is likely that telomere shortening in telomerase-depleted human cells is similarly under a complex pattern of genetic control; mechanistic understanding of this process should provide crucial information regarding how human tissues age in response to telomere erosion.

Keywords: telomeres, telomerase, replicative senescence, yeast, Rif2, MRX, Rad51

Introduction

Replicative life span was first described by Hayflick & Moorhead (1961) who demonstrated that human fibroblasts do not possess unlimited replicative potential in culture but instead are capable of only a finite number of cell divisions. The molecular basis for this “Hayflick limit” is the gradual attrition of telomeric repeats present at chromosome termini (Lundblad & Szostak, 1989; Harley et al., 1990); once telomere length falls below a critical threshold, cells irreversibly exit from the cell cycle. This block to indefinite cell division can be alleviated by the enzyme telomerase which adds telomeric DNA to chromosome ends (Greider & Blackburn, 1985), thereby preventing replicative senescence. However, telomerase is expressed at low levels in most human somatic tissues (Kim et al., 1994) which undergo progressive telomere shortening as a consequence. The vulnerability of tissues to telomere length was first revealed in patients with a rare genetically inherited deficiency due to mutations in telomerase (Mason & Bessler, 2011). However, increasing evidence indicates that short telomeres are a risk factor for age-dependent pathophysiologies among a much broader segment of the human population (Armanios, 2009; Armanios & Blackburn, 2012). The most common manifestation of telomere shortening in adults is a progressive and irreversible scarring of the lungs known as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (Tsakiri et al., 2007; Armanios et al., 2007), but telomere shortening can also lead to bone marrow failure, liver cirrhosis, or increased incidence of diabetes due to β-cell apoptosis (Savage & Alter, 2008; Hartmann et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2011).

Largely unexplored is the degree to which the proliferative ability of human cells undergoing telomere shortening can be modulated by factors other than telomerase. The potential impact of such modulation is illustrated by the spectrum of age-dependent characteristics displayed by individuals who have an identical genetically inherited defect in telomerase (Alder et al., 2011), which suggests that telomere shortening in telomerase-depleted cells may be subject to a complex pattern of genetic control. Therefore, understanding the regulatory pathways that dictate how human tissues age in response to telomere erosion is likely to provide key insights into one aspect of the aging process.

This current study employs S. cerevisiae, which provides a highly amenable experimental system for probing the genetic network that mediates replicative senescence in response to a telomere replication defect. Elimination of telomerase in budding yeast, by defects in either the catalytic core of the enzyme or three regulatory proteins, confers gradual telomere shortening and an eventual block to further cell division, referred to as the Est (ever shorter telomere) phenotype (Lundblad & Szostak, 1989; Singer & Gottschling, 1994; Lendvay et al., 1996). Replicative senescence in telomerase-defective strains of yeast is commonly assessed by monitoring the ability of individual cells to form single colonies on rich media at various intervals during continuous propagation of the strain (Lundblad & Szostak, 1989; Rizki & Lundblad, 2001). Initially, the colony-forming ability of a newly generated telomerase-defective yeast strain is indistinguishable from that of a telomerase-proficient strain, even though telomeres have already begun to shorten. However, a decline in viability becomes detectable by ~50 generations, as evidenced by an increase in the number of individual cells that no longer give rise to full-sized colonies; by ~75 to 100 generations, the majority of cells are unable to undergo sufficient cell divisions to form a colony. This gradual decline in proliferative capacity, which is a defining characteristic of a telomerase deficiency in yeast cells (Singer & Gottschling, 1994; Lingner et al., 1997), is also recapitulated in human cells (Smith & Whitney, 1980; Bodnar et al., 1997).

Many studies of telomerase-deficient yeast have focused on the ability of a small subset of cells to escape the lethal consequences of a telomerase deficiency via a recombination-dependent process, which occurs during the later stages of senescence when viability is severely impaired (Lundblad & Blackburn, 1993). This current study is instead directed at the genetic regulation of the early stages of replicative senescence, prior to the appearance of the recombination-mediated pathway. This analysis was prompted by previous observations showing that the senescence profile of a telomerase-defective strain is slightly delayed if the strain also has a defect in the TEL1 gene, even before telomeres have became critically short (Ritchie et al., 1999; Abdallah et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2010; Chang & Rothstein, 2011). We previously suggested (Gao et al., 2010) that this attenuated senescence was a reflection of Tel1’s contribution to resection of DNA termini (Mantiero et al., 2007), whereby impaired resection of chromosome ends would impact the rate of telomere shortening, with a resulting delay in the appearance of critically short telomeres and senescence. Since Tel1 modulates resection at telomeres in collaboration with other factors (Rif2 and the MRX complex; Bonetti et al., 2010; Martina et al., 2012), we examined the potential contribution of these additional proteins to viability in the absence of telomerase, which revealed that this set of proteins functions in a single pathway to regulate replicative senescence, via a genetic relationship which exactly parallels the previously demonstrated interactions between these proteins in nucleolytic processing of telomeres (Bonetti et al., 2010; Martina et al., 2012). This is not the only genetic pathway that impacts cell viability in the absence of telomerase, as we show that the Rad51 protein makes an independent contribution to replicative senescence which opposes the effects of the MRX-Tel1-Rif2 pathway. Finally, defects in two other proteins (Rif1 and Sae2) are shown to have transient effects during early or late stages of replicative senescence, respectively, indicating that these two proteins are responding to aspects of telomere dysfunction rather than contributing to the process(es) by which telomeres erode in telomerase-defective strains. These epistatic relationships suggest that the pathways that modulate telomere function in the absence of telomerase are likely to be as complex as the genetic interactions that regulate telomere length in the presence of telomerase.

Results

The MRX complex, like Tel1, regulates replicative senescence

Similar to Tel1, a defect in the MRX (Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2) complex confers reduced resection at both double-strand breaks (DSBs) and telomeres (Larrivee et al., 2004; Takata et al., 2005; Mantiero et al., 2007; Bonetti et al., 2010). This predicts that replicative senescence should be attenuated in telomerase-defective strains lacking the MRX complex, in a manner similar to the effects observed when Tel1 is absent. To test this, the impact of rad50-Δ and xrs2-Δ mutations on the phenotype of a strain lacking the telomerase RNA subunit (called TLC1 in yeast) was examined. To do so, we used an expanded version of the serial single colony propagation assay that monitors the progressive decline in growth in the absence of telomerase (Rizki & Lundblad, 2001; Gao et al., 2010). Following dissection of a tlc1-Δ/TLC1 diploid strain bearing additional mutation(s) of interest, multiple isolates of independently generated telomerase-defective strains were propagated as single colonies on solid media for ~25, ~50 and ~75 generations. Growth characteristics of each isolate were assessed genotype-blind on a scale of 6 (equivalent to wild type) to 1 (maximal senescence) at each time point, and the data were displayed either as a histogram of the entire dataset for each genotype (as shown in Fig. 1A) or as a graph of relative senescence scores (where the average score for tlc1-Δ geneX-Δ was compared to the average score for tlc1-Δ, such that positive or negative values corresponded to attenuated or enhanced senescence, respectively, relative to tlc1-Δ). The key feature of this expanded assay is the inclusion of a substantial number of biological replicates (usually 20 to 35 isolates for each genotype), which addresses the inherent variability of the senescence phenotype that arises due to sequence loss occurring at 32 distinct genetic loci (i.e. 32 chromosome termini) at each cell division. Analysis of a high number of samples also permits an evaluation of the statistical significance of potential differences between genotypes (see Gao et al., 2010 for further discussion).

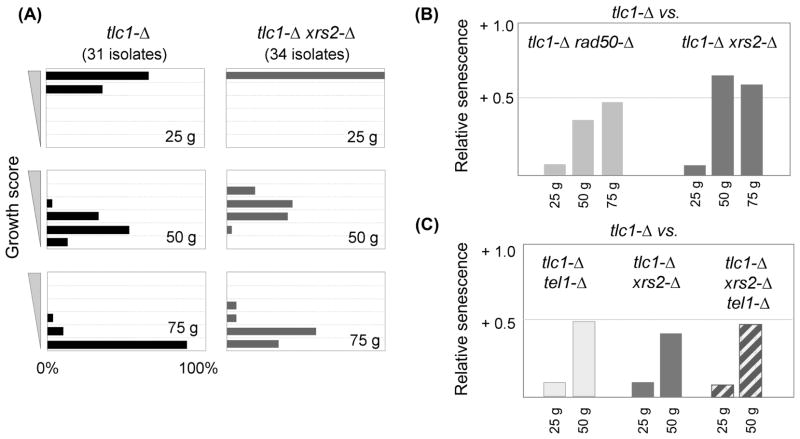

Fig. 1. The MRX complex and Tel1 regulate senescence through a common pathway.

(A) Histogram of the senescence phenotypes of 31 tlc1-Δ isolates and 34 tlc1-Δ xrs2-Δ isolates, as the percentage displaying a particular growth score (on a scale of 1 to 6) at ~25, ~50 and ~75 generations (abbreviated “g”). (B) Average senescence scores of 34 tlc1-Δ xrs2-Δ isolates or 25 tlc1-Δ rad50-Δ isolates, relative to the average score of 31 or 39 tlc1-Δ isolates, respectively, where a positive value corresponds to an attenuated senescence phenotype (relative to that of the tlc1-Δ isolates). (C) Relative senescence scores for the three indicated genotypes generated from a tlc1-Δ/TLC1 xrs2-Δ/XRS2 tel1-Δ/TEL1 diploid strain; the average of two experiments is shown, corresponding to a total of 66 tlc1-Δ, 77 tlc1-Δ xrs2-Δ, 50 tlc1-Δ tel1-Δ and 68 tlc1-Δ xrs2-Δ tel1-Δ isolates. Senescence was monitored for only ~50 generations in this experiment, because telomerase-defective strains derived from this diploid strain senesced faster, compared to the senescence progression shown in Fig. 1A.

Using this protocol, a comparison of 34 tlc1-Δ xrs2-Δ isolates with 31 tlc1-Δ isolates showed that loss of the Xrs2 subunit of the MRX complex delayed replicative senescence, with a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001) at all three time points (Fig. 1A, B). Senescence of tlc1-Δ rad50-Δ strains (25 isolates) was similarly attenuated when compared to 39 tlc1-Δ strains (p = 0.004, <0.001 or 0.001 for the 25, 50 and 75 generation time points, respectively; Fig. 1B and Fig. S1). The increased viability of tlc1-Δ rad50-Δ and tlc1-Δ xrs2-Δ strains relative to their tlc1-Δ RAD50 or tlc1-Δ XRS2 counterparts was particularly notable given that xrs2-Δ and rad50-Δ mutations confer a slight growth defect in a telomerase-proficient background (data not shown). These results indicate that the action of the MRX complex at telomeres enhances the progressive decline in replicative capacity of telomerase-deficient cells.

These observations provide further support for the model that reduced telomeric resection can partially alleviate the consequences of a telomerase deficiency. Since Tel1 positively regulates resection by promoting the activity of the MRX complex at telomeres (Martina et al., 2012), this predicts that the consequence of a tel1-Δ defect in the absence of telomerase should not be additive with rad50-Δ or xrs2-Δ mutations. To test this, two independent experiments for each set of genotypes compared replicative senescence of double mutant strains with that of the corresponding triple mutant strains. For both RAD50 and XRS2, the triple mutant strains (tlc1-Δ tel1-Δ rad50-Δ or tlc1-Δ tel1-Δ xrs2-Δ) exhibited senescence phenotypes that were statistically indistinguishable from those of the corresponding double mutant strains (Fig. 1C and S1). The lack of an additive effect argues that Tel1 and MRX act in a common pathway to promote senescence in a telomerase-defective strain, in a manner which recapitulates their genetic relationship in resection of DSBs.

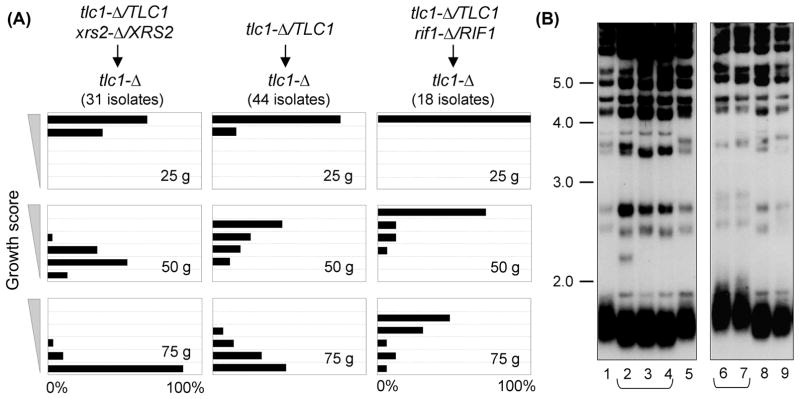

However, the results reported here on the attenuated senescence conferred by a rad50-Δ mutation, as well as similar prior observations for tel1-Δ (Ritchie et al., 1999; Abdallah et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2010; Chang & Rothstein, 2011), contradict a recent genome-wide analysis which concluded that both rad50-Δ and tel1-Δ mutations instead resulted in accelerated senescence of telomerase-defective strains (Chang et al., 2011a). In the protocol used in this current study, the growth characteristics of tlc1-Δ geneX-Δ strains were always compared to tlc1-Δ isolates generated from the same parental diploid strain. This aspect of the experimental design was crucial because the senescence profile displayed by telomerase-defective haploid strains can be substantially altered by the genotype of the parental diploid strain. This was illustrated by a comparison of the growth characteristics of isogenic sets of tlc1-Δ isolates derived from three different tlc1-Δ/TLC1 diploid strains (Fig. 2). Whereas tlc1-Δ isolates from an xrs2-Δ/XRS2 tlc1-Δ/TLC1 diploid underwent accelerated senescence (relative to tlc1-Δ strains from an otherwise wild type tlc1-Δ/TLC1 diploid), tlc1-Δ strains from a rif1-Δ/RIF1 tlc1-Δ/TLC1 diploid displayed a substantial delay in the appearance of the senescence phenotype (Fig. 2A). The differences between these three groups of isogenic haploid tlc1-Δ strains were statistically significant (p < 0.001 at the 50 and 75 generation time points) and highly reproducible. A similar accelerated senescence has been reported for tlc1-Δ isolates from a TEL1/tel1-Δ diploid, relative to isolates from a TEL1/TEL1 diploid (Abdallah et al., 2009). This phenomenon was the result of differences in telomere length in the starting diploid strains due to haploinsufficiency, as xrs2-Δ/XRS2 or tel1-Δ/TEL1 strains exhibited a slight reduction in telomere length, whereas telomeres were clearly elongated in the rif1-Δ/RIF1 diploid (Fig. 2B and data not shown). As a result, telomere length of newly generated haploid tlc1-Δ strains following dissection of each of these three diploid strains was not identical, which dictated the subsequent senescence profiles of tlc1-Δ isolates from these different strains. We suggest that similar inherited differences in telomere length in haploid strains, due to haploinsufficiency in certain diploid strains, impacted the conclusions from the genome-wide analysis reported by Lydall and colleagues (Chang et al., 2011a), in which the senescence phenotypes of tlc1-Δ geneX-Δ strains (such as tlc1-Δ rad50-Δ or tlc1-Δ tel1-Δ) were compared with that of tlc1-Δ strains derived from different diploid parents.

Fig. 2. The senescence progression of haploid tlc1-Δ isolates is influenced by haploinsufficiency in the parental diploid strain.

(A) Senescence phenotypes of tlc1-Δ strains from the indicated diploid strains; tlc1-Δ isolates from the rif1-Δ/RIF1 diploid continued to exhibit a progressive decline in growth phenotype with further propagation (data not shown). (B) Telomere length of xrs2-Δ/XRS2 tlc1-Δ/TLC1 (lanes 2–4) and rif1-Δ/RIF1 tlc1-Δ/TLC1 (lanes 6–7) diploid strains used in part (A), compared to the isogenic tlc1-Δ/TLC1 parental strain (lanes 1, 5, 8–9).

Rif2 regulates replicative senescence through the MRX/Tel1 pathway

Like Tel1 and MRX, the Rif2 protein contributes to telomere length regulation in telomerase-proficient strains (Bianchi & Shore, 2009) and also influences the growth characteristics of telomerase-defective strains (Chang et al., 2011b). As shown in Fig. 3, a rif2-Δ mutation conferred an immediate impact on the growth of a tlc1-Δ strain, with tlc1-Δ rif2-Δ isolates displaying a substantial difference when compared to isogenic tlc1-Δ strains even at the 25 generation time point; with additional propagation, replicative senescence was further accelerated (Fig. 3A and S2).

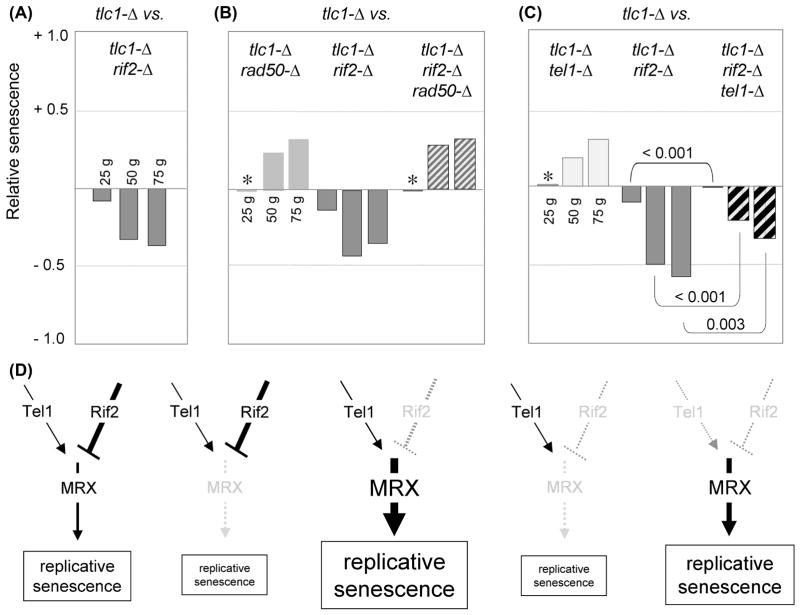

Fig. 3. Rif2 negatively regulates replicative senescence through the MRX pathway.

(A) Relative senescence scores for tlc1-Δ rif2-Δ (22 isolates) compared to tlc1-Δ (18 isolates). (B) Relative senescence scores for the indicated strains, derived from an average of two experiments (with a minimum of 25 isolates per genotype for each experiment); Fig. S2 shows statistical data for the comparison between rad50-Δ and rad50-Δ rif2-Δ for each of the two experiments. The apparent lack of an effect at the 25 generation time point for tlc1-Δ rad50-Δ (and similarly for tlc1-Δ tel1-Δ, in part C), indicated by asterisks, was a consequence of slightly elongated telomeres in the parental diploid strains (due to rif2-Δ/RIF2 haploinsufficiency; data not shown), which delayed the appearance of the senescence phenotype in the resulting tlc1-Δ and tlc1-Δ rad50-Δ isolates. (C) Relative senescence scores of the indicated strains generated following dissection of a tlc1-Δ/TLC1 rif2-Δ/RIF2 tel1-Δ/TEL1 diploid strain; an independent repeat of this experiment is shown in Fig. S2. (D) Genetic map of the epistatic relationship between Tel1, Rif2 and MRX; the severity of the replicative senescence phenotype in response to mutations in factors in the pathway is schematically represented by the size of the box.

In telomerase-proficient cells, Rif2 is an inhibitor of MRX-mediated resection, whereby the increased single-stranded DNA observed at telomeres in a rif2-Δ mutant strain is blocked by an mre11-Δ mutation (Bonetti et al., 2010). Similarly, the severe replicative senescence phenotype conferred by a rif2-Δ mutation was reversed by the loss of the MRX complex, as the senescence progression of rif2-Δ rad50-Δ or rif2-Δ xrs2-Δ telomerase-defective strains was indistinguishable from that of rad50-Δ or xrs2-Δ telomerase-defective strains (Fig. 3B and data not shown). Rif2 has been proposed to regulate MRX-dependent resection by competing with Tel1 for binding to the Xrs2 subunit of this complex (Hirano et al., 2009), which predicts that loss of Tel1 function should also alleviate the consequences of a rif2-Δ mutation on a telomerase-defective strain. Indeed, the rapid replicative senescence displayed by a tlc1-Δ rif2-Δ strain was partially reversed by loss of Tel1 function. The severity of phenotype of the triple mutant tlc1-Δ rif2-Δ tel1-Δ (28 isolates) was attenuated at all three time points, when compared to the rapid senescence displayed by 36 tlc1-Δ rif2-Δ isolates (Fig. 3C and S2), with a difference that was statistically significant (p = < 0.001, <0.001 and 0.003 for the 25, 50 and 75 generation time points, respectively); similar results were reported by Chang & Rothstein, 2011. The triple mutant strain nevertheless exhibited a senescence phenotype that was still more pronounced than that of an otherwise wild type tlc1-Δ strain (Fig. 3C). The inability of a tel1-Δ mutation to fully reverse the consequences of a rif2-Δ defect is consistent with prior observations showing that positive regulation by Tel1 is not absolutely essential for MRX-dependent nucleolytic processing (in other words, the negative and positive regulatory effects of Rif2 and Tel1 are not equally balanced; Martina et al., 2012).

Fig. 3D places these epistasis results in a genetic pathway for regulation of senescence in a telomerase-defective strain, with the Rif2 and Tel1 regulatory proteins upstream of the MRX complex. In strains lacking the MRX complex, replicative senescence is partially attenuated. In contrast, loss of the negative regulator, Rif2, results in rapid senescence due to increased activity of the MRX complex at telomeres; this accelerated senescence is reversed, however, when the MRX complex is no longer present (and partially reversed by the loss of the Tel1 positive regulator). Notably, the genetic relationships that we observe here in the absence of telomerase exactly parallel the relationships between these proteins in the resection pathway (Bonetti et al., 2010; Martina et al., 2012). This correlation between delayed senescence and impaired resection suggests that the action of the MRX complex may enhance the rate of telomere shortening in tlc1-Δ strains. If so, the effects are modest enough that changes in telomere length of telomerase-defective strains in response to defects in the MRX complex cannot be observed by standard Southern blot protocols (see Fig. 2 in Nugent et al., 1998). However, even a single very short telomere can confer accelerated senescence (Abdallah et al., 2009); therefore, a small change in the number of critically short telomeres may be sufficient to alter the senescence profile of a tlc1-Δ strain in response to MRX activity but escape detection by protocols that monitor average telomere length.

Rad51 regulates replicative senescence through an independent pathway acting in opposition to the MRX-Tel1-Rif2 pathway

Previous work has implicated RAD51 in the formation of survivors which arise late in the outgrowth of telomerase-defective strains in response to extreme telomere erosion (Le et al. 1999). In addition, a rad51-Δ mutation confers a substantial growth phenotype even in the earliest stages of propagation of telomerase-defective strains (Le et al., 1999), indicating that loss of RAD51 function confers accelerated replicative senescence well before effects on the late-stage appearance of the survivor pathway. In the DSB repair pathway, Rad51 acts downstream of MRX-mediated resection by binding the exposed single-stranded DNA in order to initiate homologous recombination (Costanzo, 2011). If Rad51 similarly acts downstream of the MRX complex to mediate events in the absence of telomerase, the dramatic enhancement of senescence conferred by a rad51-Δ mutation should be reversed by loss of the MRX complex. In contrast to this expectation, the triple mutant tlc1-Δ rad50-Δ rad51-Δ strain exhibited a phenotype that was intermediate between either of the two double mutant strains (Fig. 4A). This argues that RAD51 and RAD50 act in two separate, and opposing, pathways to regulate replicative senescence.

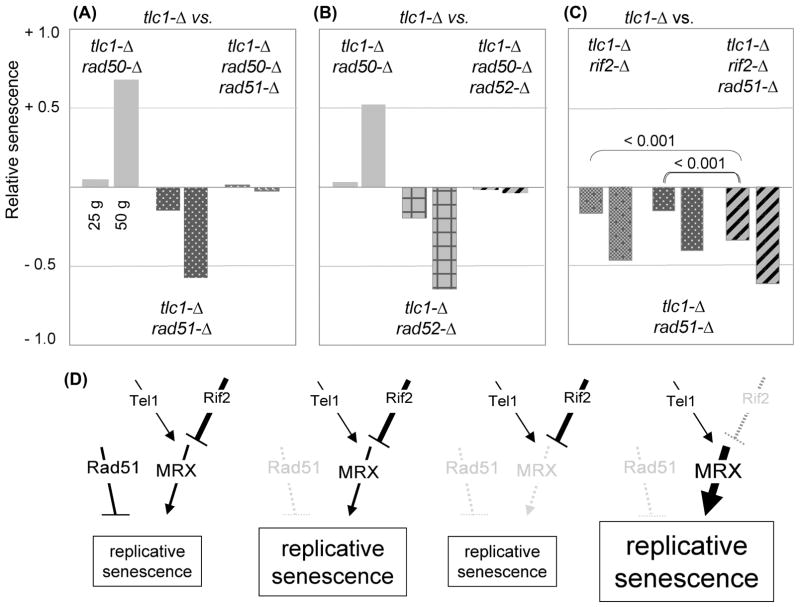

Fig. 4. Rad51 and Rad52 affect replicative senescence in opposition to the MRX pathway.

(A) through (C) Relative senescence scores for the indicated genotypes (20 to 32 isolates for each genotype); histograms of the senescence phenotypes for each experiment, as well as the number of isolates tested for each genotype, are shown in Fig. S3. Independent repeats of the experiments shown in (A) and (B) performed by each of the two co-authors produced essentially identical results. (D) Schematic illustration of the impact of mutations in two pathways that act in opposition to each other to regulate replicative senescence; see text for discussion.

We also tested the epistatic relationship between RAD50 and RAD52, as loss of RAD52 function also has a profound negative impact on the early stage growth of telomerase-defective strains (Lundblad & Blackburn, 1993). Once again, the pronounced senescence progression of tlc1-Δ rad52-Δ strains was partially reversed by the presence of a rad50-Δ mutation (Fig. 4B). In both cases, the viability profiles of the triple mutant tlc1-Δ rad51-Δ rad50-Δ and tlc1-Δ rad52-Δ rad50-Δ strains were essentially indistinguishable from the behavior of a single mutant tlc1-Δ strain at the 25 and 50 generation time points (Fig. S3). Since these effects were observed within the first 25 to 50 generations of growth of a telomerase-defective strain, these epistatic interactions are also distinct from prior observations of how RAD50, RAD51 and RAD52 influence the appearance of survivors during later stages of propagation of telomerase null strains (Chen et al. 2001). We conclude that in telomerase-defective strains, RAD50 acts at telomeres in opposition to both RAD51 and RAD52.

The premise that Rad51 acts in a distinct pathway from the MRX complex in replicative senescence was also supported by epistasis analysis with the Rif2 negative regulator of MRX function. As would be predicted if Rif2 and Rad51 were functioning in separate pathways, an additive effect on senescence at the 25 generation time point was observed when rad51-Δ and rif2-Δ mutations were combined (Fig. 4C). A statistically significant additive effect was less evident at later time points, because senescence was accelerated for all of the telomerase-defective strains in this experiment (even tlc1-Δ isolates; Fig. S3). As a consequence, the majority of isolates for the double and triple mutant genotypes were inviable by 50 generations (Fig. S3), which precluded any meaningful comparisons at this time point. In contrast to the enhancement of a rif2-Δ mutation, loss of Tel1 function resulted in a very slight reversal of the senescence progression of a tlc1-Δ rad51-Δ strain (data not shown); the modest impact of the tel1-Δ mutation is once again presumably due to the fact that MRX activity is not completely abolished in a tel1-Δ strain. Collectively, the observations shown in Fig. 4A–C support a model in which the MRX-Te1-Rif2 and Rad51 pathways make separate regulatory contributions to replicative senescence, as depicted in Fig. 4D.

The Sae2 protein makes a transient contribution during late stages of replicative senescence

In addition to the MRX complex, efficient processing of DSBs in budding yeast also requires the Sae2 protein, as the combined contributions of these two activities are essential for the first step in resection of 5′ strands to generate a single-stranded 3′ DNA extension (Paull, 2010; Mimitou & Symington, 2011). Sae2 also contributes to the MRX-dependent production of 3′ overhangs in a de novo telomere assay (Bonnetti et al., 2009). These prior observations suggested that a sae2-Δ mutation would have an effect similar to the attenuated senescence imparted by mutations in the MRX complex. However, in striking contrast to this expectation, loss of Sae2 function had no impact on the viability of a tlc1-Δ strain during the first ~50 generations of growth (Fig. 5A). This result is concordant with the fact that Sae2 is not required for processing of native telomeres (Bonnetti et al., 2009), in contrast to the well-established role of the MRX complex in this process. Like the Rad51 epistasis data, the lack of a Sae2-dependent effect also challenges the proposed mechanistic parallels between the processing of experimentally induced DSBs vs. native telomeres.

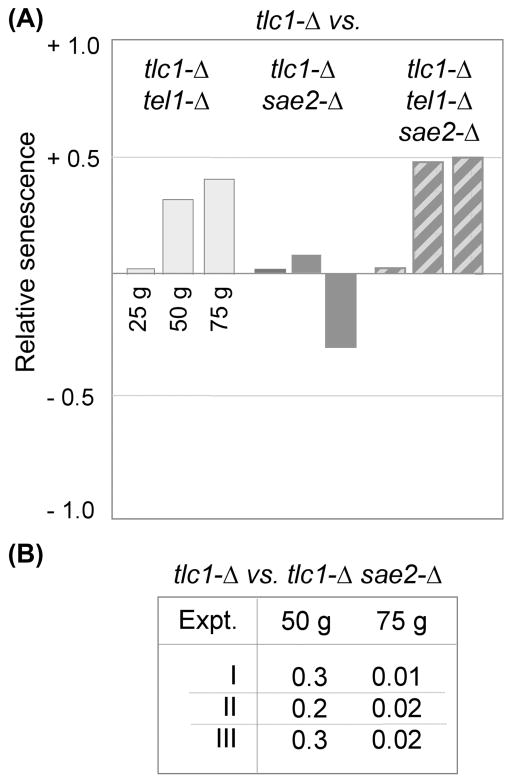

Fig. 5. Loss of SAE2 function only becomes apparent in telomerase-defective strains late in senescence.

(A) Relative senescence scores for tlc1-Δ sae2-Δ (20 isolates) and tlc1-Δ sae2-Δ tel1-Δ (15 isolates), with each compared to tlc1-Δ (25 isolates); a second independent experiment similarly showed that a sae2-Δ mutation had no impact on the attenuated senescence conferred by a tel1-Δ mutation (data not shown). (B) Summary of p-values for the difference between the senescence scores for tlc1-Δ and tlc1-Δ sae2-Δ strains at 50 and 75 generations for three independent experiments (comparing 28 vs. 36, 25, vs. 20 and 26 vs. 25 isolates of tlc1-Δ vs. tlc1-Δ sae2-Δ, respectively); the histogram of the data for Experiment I is shown in Fig. S5.

Despite the inability of a sae2-Δ mutation to influence viability during early stages, senescence was nevertheless exacerbated during later stages of propagation of tlc1-Δ sae2-Δ strains (Fig. 5 and S5). The late-generation decline in cell viability that was observed in the absence of Sae2 was highly reproducible, as it was observed in three independent experiments which compared a total of 79 tlc1-Δ isolates with 81 tlc1-Δ sae2-Δ isolates (Fig. 5B). The fact that a Sae2 defect was evident only after telomeres became critically short argued that the Sae2 protein was not contributing to the progression of replicative senescence but instead was responding to the consequences (such as a signal generated by critically short telomeres). Consistent with this supposition, the Sae2-mediated response was Tel1-dependent, as Sae2 was completely dispensable in a tel1-Δ strain, even at late points during replicative senescence (Fig. 5A). This suggests that Sae2 responds to a Tel1-dependent event which occurs at (or is triggered by) ultra short chromosome termini.

We also considered an alternative possibility for the lack of a Sae2-dependent effect during the early stages of growth in the absence of telomerase, based on prior work showing a resection defect at native telomeres which could only be observed in sae2-Δ sgs1-Δ double mutant strains but not in either single mutant strain (Bonetti et al., 2009). This argued that the maintenance of 3′ single-stranded G-strand overhangs in telomerase-proficient cells relied on partially redundant pathways that required Sae2 and Sgs1, which suggested that a similar redundancy might be masking an effect on replicative senescence. However, dissection of a sae2-Δ/SAE2 sgs1-Δ/SGS1 diploid revealed that the sae2-Δ sgs1-Δ mutant strain had a severe synthetic growth defect even in a telomerase-proficient background (Fig. S5), which is consistent with prior observations (Pan et al., 2006). The nearly inviable phenotype conferred by combined mutations in SAE2 and SGS1 therefore precluded analysis of a potential redundant contribution to the senescence progression of a telomerase-deficient strain.

The Rif1 protein makes a transient contribution during early stages of replicative senescence

In contrast to the effects of rif2-Δ on replicative senescence, comparison of a tlc1-Δ rif1-Δ strain with tlc1-Δ did not reveal a significant impact of the loss of Rif1 function in the absence of telomerase, even when examined for ~100 generations (Fig. 6A and S4). We considered that the lack of an apparent effect of the rif1-Δ mutation might be masked due to the substantial delay in the progression of replicative senescence exhibited by telomerase-defective strains derived from a rif1-Δ/RIF1 diploid strain, as described in Fig. 2. However, a similar lack of an effect was observed when comparing tlc1-Δ and tlc1-Δ rif1-Δ strains recovered from a tlc1-Δ/TLC1 rif1-Δ/RIF1 tel1-Δ/TEL1 diploid, in which senescence in the resulting haploid telomerase-defective isolates was accelerated as a consequence of TEL1 heterozygosity (Fig. S4). Collectively, based on a comparison of RIF1 vs. rif1-Δ telomerase-defective strains from five independent experiments (corresponding to ~125 isolates of each genotype), we were unable to detect a statistically significant contribution of Rif1 to replicative senescence. The differential effects of Rif1 and Rif2 on replicative senescence reported here are also consistent with genome-wide epistasis studies showing that rif1-Δ and rif2-Δ mutations have very different genetic interaction profiles (Addinall et al., 2010), indicative of distinct roles in telomere biology.

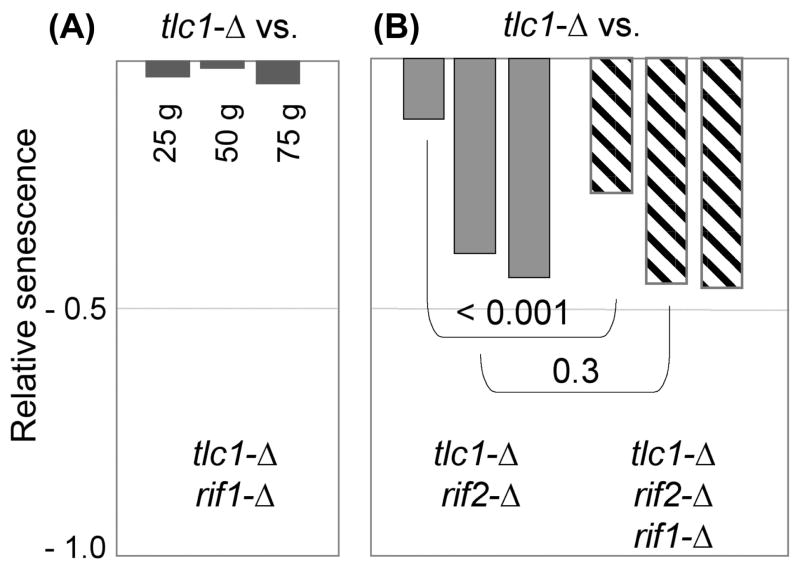

Fig. 6. Rif1 has a transient effect during early stages of replicative senescence in a rif2-Δ background.

Relative senescence scores for (A) tlc1-Δ rif1-Δ (26 isolates) compared to 18 isolates of tlc1-Δ, and (B) tlc1-Δ rif2-Δ and tlc1-Δ rif2-Δ rif1-Δ (25 and 24 isolates, respectively) compared to 28 isolates of tlc1-Δ. The comparison in part (B) shows relative senescence scores at 50, 75 and 100 generations; the histogram of the data for this experiment is shown in Fig. S4.

Under one genetic situation, however, a transient contribution by Rif1 in response to telomere erosion was observed. During the initial propagation of telomerase-defective strains lacking both Rif1 and Rif2, there was a significant enhancement in the severity of replicative senescence of tlc1-Δ rif1-Δ rif2-Δ strains, relative to tlc1-Δ rif2-Δ strains (Fig. 6B). This enhancement was reproducibly observed only in the early stages of senescence; as cells continued to be propagated, the senescence profile of the triple mutant strain became indistinguishable from that of the double mutant strain. The inability to differentiate between genotypes at later time points was not due to a problem with inviability, as noted above for the rif2-Δ rad51-Δ epistasis experiment, as the majority of isolates for this experiment could be propagated for at least 100 generations, until inviability prevented further analysis (Fig. S4). This short-lived impact during early stages of senescence further argues that Rif1 is contributing to replicative senescence through a mechanism which is distinct from the MRX-Tel1-Rif2 pathway.

Discussion

Increasing evidence indicates that telomere maintenance is a substantial contributing factor to the human aging process. Telomerase is down-regulated in most tissues, and therefore whether telomeres erode at a faster or shorter rate will dictate proliferation limits. This argues that understanding the genetic control of cellular proliferation in the absence of telomerase will be as vital as figuring out the pathways that regulate telomere length in the presence of telomerase. In this study, we have used telomerase-defective strains of budding yeast to investigate this problem. Our starting point was prior analysis of the behavior of telomerase-defective strains that also lack the Tel1 protein. Although TEL1 was first discovered based on the short telomere length phenotype displayed by telomerase-proficient tel1-Δ strains (Lustig & Petes, 1986), we and others have shown that loss of Tel1 function partially attenuates the senescence phenotype of a tlc1-Δ strain. This suggests that other factors, first identified on the basis of phenotypes in telomerase-proficient strains, might similarly impact replicative senescence. Consistent with this premise, our data show that the Tel1, Rif2 and MRX proteins comprise an epistasis group that influences replicative senescence in a manner that exactly parallels their behavior in telomerase-proficient cells.

A current model for these proteins, largely supported by work from the Longhese laboratory, suggests that their role at telomeres is to mediate resection (Mantiero et al., 2007; Bonetti et al., 2010; Martina et al., 2012). This provides an appealing molecular basis for explaining the array of phenotypes that result when these factors are absent in either telomerase-proficient or telomerase-deficient cells. In cells undergoing telomere shortening due to a telomerase deficiency, an altered rate of resection could impact the rate of erosion of chromosome ends and hence senescence. In contrast, in the presence of telomerase, reduced resection could create chromosomal termini which are no longer optimal substrates for telomerase, as previously proposed (Gao et al., 2010), thereby explaining the reduced telomere length observed in tel1-Δ and mrx-Δ strains (and conversely, telomere elongation in rif2-Δ strains).

However, the consequences of a rad51-Δ mutation for a telomerase-deficiency do not easily fit into the above picture. Although Rad51 acts downstream of the MRX complex in DSB repair, Rad51 makes a contribution to replicative senescence in opposition to the MRX pathway. The recent demonstration that Rad51 has a separate role in DNA replication, in which nascent DNA bound by Rad51 is protected from MRX-mediated degradation at stalled replication forks, potentially provides an explanation (reviewed by Constanzo 2011). The opposing roles for Rad51 and the MRX complex in DNA replication, which mirror the effects of these factors on replicative senescence, may suggest a common molecular mechanism, whereby RAD51 function ensures continuous replication of the duplex telomeric DNA.

An unanticipated observation from this analysis was that loss of SAE2 function had no discernible effect on replicative senescence until telomeres had become critically short, in contrast to the immediate impact exhibited by telomerase-defective cells that were deficient in the MRX complex. This is discordant with the role of these proteins in DSB repair, as the current model postulates that MRX and Sae2 collaborate to facilitate resection of newly generated DSBs (Paull, 2010). This distinction may be due to differing substrates (i.e. differences in the structure of DNA termini) that are monitored in DSB assays vs. replicative senescence. A key assay for DSB repair (as well as de novo telomere formation; Diede & Gottschling, 1999) monitors how cells process DSBs experimentally induced by the HO endonuclease, which creates a substrate with a defined 4-nucleotide overhang (Haber, 2002). Dissimilarities between the structure of natural chromosome ends and HO-generated breaks may be sufficient to shunt telomeres and DSBs into distinct resection pathways, which might offer an explanation for the effects of Sae2 and MRX on DSB repair vs. replicative senescence.

Also unexpected was the lack of an effect on senescence when RIF1 was absent. Although the results reported here for rif1-Δ are supported by a prior study, which similarly failed to detect a difference in the senescence profiles when multiple est2-Δ RIF1 vs. est2-Δ rif1-Δ isolates were compared (Anbalagan et al., 2011), data from several other groups have observed that loss of RIF1 function accelerated the loss of viability in strains lacking telomerase (Chang et al., 2011a; Chang et al., 2011b). This is not the only disagreement with regard to how genetic perturbations might impact senescence, as strikingly different conclusions have been reported on the contribution of the four SIR genes to the proliferation of telomerase-defective strains. Lowell et al., 2003 observed a notable suppression of senescence when any of the four SIR genes were deleted, with this effect phenocopied by simultaneous expression of both MATa and MATα information. In contrast, Kozak et al., 2010 reported that sir3-Δ and sir4-Δ deletions delayed or enhanced senescence, respectively, whereas sir2-Δ had no impact. These differing results may reflect different assay methods, but also underscore the difficulty of monitoring a phenotype which exhibits such variability.

In summary, this study lends support to the idea that telomere erosion in the absence of telomerase is likely to be a highly dynamic process. With each cell division, the duplex telomeric tract must be completely replicated, with the newly synthesized termini subsequently converted into mature telomeres. Variations in several steps in this process – such as incomplete progression of the replisome through duplex telomeric DNA, variable positioning of the terminal Okazaki fragment or variations in the rates of nucleolytic processing of newly replicated blunt termini – can potentially impact the rate of telomere erosion (Lundblad, 2012). In addition, telomeres may become vulnerable to ectopic resection activities, particularly in later stages when critically short telomeres are no longer adequately protected. Each of these molecular mechanisms are potentially under the control of one or more genetic regulators, with defects at any step of each of these pathways contributing to the rate of DNA loss from chromosome ends. Therefore, the work presented here, as well as many prior studies that have examined the genetic impact of numerous gene deletions on the early stages of senescence (Lundblad & Blackburn, 1993; Le et al., 1999; Ritchie et al., 1999; Rizki & Lundblad, 2001; Chen et al., 2001; Lowell et al., 2003; Enomoto et al., 2004); Abdallah et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2010; Kozak et al., 2010; Chang & Rothstein, 2011; Chang et al., 2011a; Noël & Wellinger 2011), indicates that a complex network of pathways controls telomere erosion in telomerase-defective cells.

Experimental Procedures

All yeast strains used in this study, which are listed in Table S1, were derived from a parental diploid tlc1-Δ/TLC1 strain and thus isogenic, with mutations introduced using standard genetic methods. The protocol for the serial single colony propagation assay was as follows: For each experiment, a diploid strain was sporulated in liquid sporulation medium for ~4 to 5 days at 30° and 50 to 70 tetrads were dissected on rich media plates (YPAD). Following incubation at 30° for three days, tlc1-Δ isolates from the dissection plate were streaked for single colonies on rich media plates and grown at 30° for 72 hours (the ~25 generation time point). Strains were propagated for two to three successive streak-outs, with average-sized colonies chosen at each time point with no bias with regard to colony size. As needed, streak-outs were allowed to grow for an additional 1 to 2 days to allow those streak-outs that were composed of significantly smaller colonies to catch up, thereby ensuring that cells used to initiate the next set of streak-outs had undergone the same number of cell divisions. Each experiment was concluded when a substantial number of isolates either scored as “2” (barely growing) or “1” (no growth). Growth phenotypes were scored from photographs of each set of streak-outs, by comparison to a set of standards (see Gao et al., 2010); independent scoring of the growth phenotypes by either co-author of roughly half of the experiments performed in this study resulted in virtually indistinguishable relative senescence scores. Genotyping of mating type and other mutation(s) was performed and recorded separately. At the conclusion of the experiment, the complete genotype(s) were unblinded and the data were displayed as a histogram of the distribution of scores for each genotype at each time point (i.e. ~25, 50 and 75 generations) or as the average score for tlc1-Δ geneX-Δ compared to the average score for tlc1-Δ as positive or negative values (indicating attenuated or enhanced senescence, respectively). Comparisons of telomerase-defective strains of different genotypes always employed isolates derived from the same diploid strain (except for the experiment shown in Fig. 2). Each epistasis experiment was performed at least twice (i.e. the relevant diploid strain was re-sporulated and dissected to generate an independent set of haploid isolates), with most experiments performed three times.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Johnathan W. Lubin for providing the Southern blot shown in Fig. 2 and Margherita Paschini for critical discussions. This research was supported by National Institute of Health grant R37 AG11728 (to V.L.) and Cancer Center Core grant P30 CA014195 (to the Salk Institute).

Footnotes

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Abdallah P, Luciano P, Runge KW, Lisby M, Géli V, Gilson E, Teixeira MT. A two-step model for senescence triggered by a single critically short telomere. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:988–993. doi: 10.1038/ncb1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alder JK, Cogan JD, Brown AF, Anderson CJ, Lawson WE, Lansdorp PM, Phillips JA, 3rd, Loyd JE, Chen JJ, Armanios M. Ancestral mutation in telomerase causes defects in repeat addition processivity and manifests as familial pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armanios MY, Chen JJ, Cogan JD, Alder JK, Ingersoll RG, Markin C, Lawson WE, Xie M, Vulto I, Phillips JA, 3rd, Lansdorp PM, Greider CW, Loyd JE. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1317–1326. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armanios M. Syndromes of telomere shortening. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:45–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-150046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armanios M, Blackburn EH. The telomere syndromes. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:693–704. doi: 10.1038/nrg3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi A, Shore D. Telomere length regulation: coupling DNA end processing to feedback regulation of telomerase. EMBO J. 2009;28:2309–2322. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar AG, Ouellette M, Frolkis M, Holt SE, Chiu CP, Morin GB, Harley CB, Shay JW, Lichtsteiner S, Wright WE. Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells. Science. 1998;279:349–352. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti D, Martina M, Clerici M, Lucchini G, Longhese MP. Multiple pathways regulate 3′ overhang generation at S. cerevisiae telomeres. Mol Cell. 2009;35:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti D, Clerici M, Manfrini N, Lucchini G, Longhese MP. The MRX complex plays multiple functions in resection of Yku- and Rif2-protected DNA ends. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HY, Lawless C, Addinall SG, Oexle S, Taschuk M, Wipat A, Wilkinson DJ, Lydall D. Genome-wide analysis to identify pathways affecting telomere-initiated senescence in budding yeast. G3 (Bethesda) 2011a;1:197–208. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M, Dittmar JC, Rothstein R. Long telomeres are preferentially extended during recombination-mediated telomere maintenance. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011b;18:451–456. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M, Rothstein R. Rif1/2 and Tel1 function in separate pathways during replicative senescence. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:3798–3799. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.21.18095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Ijpma A, Greider CW. Two survivor pathways that allow growth in the absence of telomerase are generated by distinct telomere recombination events. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1819–1827. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.5.1819-1827.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo V. Brac2, Rad51 and Mre11: performing balancing acts on replication forks. DNA Repair. 2011;10:1060–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diede SJ, Gottschling DE. Telomerase-mediated telomere addition in vivo requires DNA primase and DNA polymerases alpha and delta. Cell. 1999;99:723–733. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto S, Glowczewski L, Lew-Smith J, Berman JG. Telomere cap components influence the rate of senescence in telomerase-deficient yeast cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:837–845. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.2.837-845.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Toro TB, Paschini M, Braunstein-Ballew B, Cervantes RB, Lundblad V. Telomerase recruitment in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is not dependent on Tel1-mediated phosphorylation of Cdc13. Genetics. 2010;186:1147–1159. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.122044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts. Cell. 1985;43:405–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo N, Parry EM, Li LS, Kembou F, Lauder N, Hussain MA, Berggren PO, Armanios M. Short telomeres compromise β-cell signaling and survival. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber JE. Uses and abuses of HO endonuclease. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:141–164. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)50961-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley CB, Futcher AB, Greider CW. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature. 1990;345:458–460. doi: 10.1038/345458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann D, Srivastava U, Thaler M, Kleinhans KN, N’kontchou G, Scheffold A, Bauer K, Kratzer RF, Kloos N, Katz SF, Song Z, Begus-Nahrmann Y, Kleger A, von Figura G, Strnad P, Lechel A, Günes C, Potthoff A, Deterding K, Wedemeyer H, Ju Z, Song G, Xiao F, Gillen S, Schrezenmeier H, Mertens T, Ziol M, Friess H, Jarek M, Manns MP, Beaugrand M, Rudolph KL. Telomerase gene mutations are associated with cirrhosis formation. Hepatology. 2011;53:1608–1617. doi: 10.1002/hep.24217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayflick L, Moorhead P. The serial cultivation of human diploid strains. Exp Cell Res. 1961;25:585–621. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano Y, Fukunaga K, Sugimoto K. Rif1 and rif2 inhibit localization of tel1 to DNA ends. Mol Cell. 2009;33:312–322. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, Harley CB, West MD, Ho PL, Coviello GM, Wright WE, Weinrich SL, Shay JW. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science. 1994;266:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.7605428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak ML, Chavez A, Dang W, Berger SL, Ashok A, Guo X, Johnson FB. Inactivation of the Sas2 histone acetyltransferase delays senescence driven by telomere dysfunction. EMBO J. 2010;29:158–170. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrivee M, Lebel C, Wellinger RJ. The generation of proper constitutive G-tails on yeast telomeres is dependent on the MRX complex. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1391–1396. doi: 10.1101/gad.1199404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le S, Moore JK, Haber JE, Greider CW. RAD50 and RAD51 define two pathways that collaborate to maintain telomeres in the absence of telomerase. Genetics. 1999;152:143–152. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.1.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendvay TS, Morris DK, Sah J, Balasubramanian B, Lundblad V. Senescence mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with a defect in telomere replication identify three additional EST genes. Genetics. 1996;144:1399–1412. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingner J, Hughes TR, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Lundblad V, Cech TR. Reverse transcriptase motifs in the catalytic subunit of telomerase. Science. 1997;276:561–567. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5312.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell JE, Roughton AI, Lundblad V, Pillus L. Telomerase-independent proliferation is influenced by cell type in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2003;164:909–921. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.3.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad V, Blackburn EH. An alternative pathway for yeast telomere maintenance rescues est1-senescence. Cell. 1993;73:347–360. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90234-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad V, Szostak JW. A mutant with a defect in telomere elongation leads to senescence in yeast. Cell. 1989;57:633–643. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad V. Telomere end processing: unexpected complexiity at the end game. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1123–1127. doi: 10.1101/gad.195339.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig AJ, Petes TD. Identification of yeast mutants with altered telomere structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1398–1402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.5.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantiero D, Clerici M, Lucchini G, Longhese MP. Dual role for Saccharomyces cerevisiae Tel1 in the checkpoint response to double-strand breaks. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:380–387. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martina M, Clerici M, Baldo V, Bonetti D, Lucchini G, Longhese MP. A balance between Tel1 and Rif2 activities regulates nucleolytic processing and elongation at telomeres. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:1604–1617. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06547-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason PJ, Bessler M. The genetics of dyskeratosis congenita. Cancer Genet. 2011;204:635–645. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimitou EP, Symington LS. DNA end resection - unraveling the tail. DNA Repair. 2011;10:344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noël JF, Wellinger RJ. Abrupt telomere losses and reduced end-resection can explain accelerated senescence of Smc5/6 mutants lacking telomerase. DNA Repair. 2011;10:271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent CI, Bosco G, Ross LO, Evans SK, Salinger AP, Moore JK, Haber JE, Lundblad V. Telomere maintenance is dependent on activities required for end repair of double-strand breaks. Curr Biol. 1998;8:657–660. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X, Ye P, Yuan DS, Wang X, Bader JS, Boeke JD. A DNA integrity network in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell. 2006;124:1069–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paull TT. Making the best of the loose ends: Mre11/Rad50 complexes and Sae2 promote DNA double-strand break resection. DNA Repair. 2010;9:1283–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie KB, Mallory JC, Petes TD. Interactions of TLC1 (which encodes the RNA subunit of telomerase), TEL1, and MEC1 in regulating telomere length in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6065–6075. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizki A, Lundblad V. Defects in mismatch repair promote telomerase-independent proliferation. Nature. 2001;411:713–716. doi: 10.1038/35079641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage SA, Alter BP. The role of telomere biology in bone marrow failure and other disorders. Mech Ageing Dev. 2008;29:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer MS, Gottschling DE. TLC1: template RNA component of Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomerase. Science. 1994;266:404–409. doi: 10.1126/science.7545955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JR, Whitney RG. Intraclonal Variation in Proliferative Potential of Human Diploid Fibroblasts: Stochastic Mechanism for Cellular Aging. Science. 1980;207:82–84. doi: 10.1126/science.7350644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata H, Tanaka Y, Matsuura A. Late S Phase-Specific Recruitment of Mre11 Complex Triggers Hierarchical Assembly of Telomere Replication Proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 2005;17:573–583. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsakiri KD, Cronkhite JT, Kuan PJ, Xing C, Raghu G, Weissler JC, Rosenblatt RL, Shay JW, Garcia CK. Adult onset pulmonary fibrosis caused by mutations in telomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7552–7557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701009104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.