Abstract

The aim of the present report was to evaluate the effectiveness and impact of multisensory and cognitive stimulation on improving cognition in elderly persons living in long-term-care institutions (institutionalized [I]) or in communities with their families (noninstitutionalized [NI]). We compared neuropsychological performance using language and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) test scores before and after 24 and 48 stimulation sessions. The two groups were matched by age and years of schooling. Small groups of ten or fewer volunteers underwent the stimulation program, twice a week, over 6 months (48 sessions in total). Sessions were based on language and memory exercises, as well as visual, olfactory, auditory, and ludic stimulation, including music, singing, and dance. Both groups were assessed at the beginning (before stimulation), in the middle (after 24 sessions), and at the end (after 48 sessions) of the stimulation program. Although the NI group showed higher performance in all tasks in all time windows compared with I subjects, both groups improved their performance after stimulation. In addition, the improvement was significantly higher in the I group than the NI group. Language tests seem to be more efficient than the MMSE to detect early changes in cognitive status. The results suggest the impoverished environment of long-term-care institutions may contribute to lower cognitive scores before stimulation and the higher improvement rate of this group after stimulation. In conclusion, language tests should be routinely adopted in the neuropsychological assessment of elderly subjects, and long-term-care institutions need to include regular sensorimotor, social, and cognitive stimulation as a public health policy for elderly persons.

Keywords: aging, multisensory stimulation, cognition, language, impoverished environment, long-term-care institutions

Introduction

Aging is associated with cognitive decline, which affects memory, language, executive functions, and the speed of information processing. This may worsen or improve depending on genetics,1 epigenetics,1–4 and lifestyle.5,6 These influences should be investigated further to guide public policies.7,8 Epidemiological studies have correlated physical and cognitive inactivity with a higher risk of age-related cognitive decline,9,10 while an active lifestyle may help prevent cognitive impairment in old age,11 a topic that was recently reviewed.5 Consistent with this view, the decline in memory and language that is associated with normal or pathological aging seems to be aggravated after institutionalization.12,13 Institutionalization is associated with an impoverished environment, as well as reduced sensorimotor and cognitive stimulation, social interactions, and physical activity, which contribute to a sedentary lifestyle.12

We previously examined the effects of environmental impoverishment on episodic-like and spatial memories in aged mice.14 Environmental enrichment has been defined as a combination of complex physical activity and social stimulation, reproduced in animal cages with running wheels, ropes, bridges, tunnels, and toys that are changed periodically.15,16 We demonstrated that mice maintained in enriched environments generally performed well on the spatial memory tasks on the Morris water maze and perfectly distinguished between old and recent and between displaced and stationary objects in the episodic-like memory tests, whereas individual mice maintained in impoverished cages lost those abilities.14 Morris water maze and episodic-like memory tasks have been previously detailed.17,18

In the present report, we aimed to investigate this hypothesis in elderly subjects and test the effects of multisensory and cognitive stimulation (enriched stimulation) on Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and selected language-test scores. Cognitive and multisensory stimulation is an intervention for people with or without dementia, and offers a range of enjoyable activities that provide general stimulation for thinking, concentration, and memory, as well as ludic activities, such as dancing and music, usually in a social setting, such as a small group.15,16,19–21 The selected language tests included the Boston Naming Test, Semantic Verbal Fluency (SVF), Phonological Verbal Fluency (PVF), Montréal d’Evaluation de la Communication (MEC), and the Boston Cookie Theft picture-description task to measure spontaneous language production in elderly subjects, as previously described.22 We compared the scores from institutionalized elderly subjects (impoverished environment) with noninstitutionalized (enriched environment) age-matched subjects. Each subject was compared with his/herself at different time windows, before and after multisensory and cognitive stimulation. Our results indicated multisensory and cognitive stimulation should be included in permanent health policies for elderly persons living in long-term-care institutions.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the local research ethics committee, and all principles of ethics related to research involving human subjects were observed. All subjects and/or institutions agreed to participate voluntarily and provided written consent. The present study was interventional, longitudinal, and analytical, and was developed at the Laboratory of Investigations in Neurodegeneration and Infection of the Institute of Biological Sciences at the University Hospital João de Barros Barreto in the city of Belém, Brazil.

Subjects

Participants were aged 65 or older with no history of head trauma, stroke, primary depression, or chronic alcoholism. All older participants were considered cognitively healthy with appropriate MMSE scores, adjusted for education level with the following cutoff points: illiterates, 13; 1–7 years of schooling, 18; ≥8 years of schooling, 26.23 All patients who met these criteria were assessed with selected language tests and the MMSE, followed by 48 sessions of multisensory and cognitive stimulation. Volunteers were divided into two groups, matched for age and years of education: institutionalized (I; n=25, 76.0±6.9 years old, 4.7±4.5 years of schooling; those who live in long-term-care institutions), and noninstitutionalized (NI; n=17, 74.2±4.0 years old, 6.8±3.6 years of schooling; those who live in communities with their families). On average, the length of institutionalization was 8.8±3.45 years (mean ± standard deviation), and all long-term-care institutions were under similar internal rules and environmental conditions. NI elderly were living in the community with one or more family members.

Language assessment

Language was assessed with the following tests, detailed in Table S1.

The Boston Naming Test (shortened version) was administered and analyzed according to parameterized data for Brazil,24,25 adopting a cutoff equivalent to twelve of 15 possible figures named correctly. For SVF and PVF, tests of phonological and semantic verbal fluency were administered and computed using the following cutoff points: <9 points for illiterates, <12 points for 1–7 years of schooling, and <13 points for individuals with 8 years or more of schooling.26 The Cookie Theft test was evaluated using previously published criteria on the information content of the image, including the number of key concepts, narrative efficiency, number of units of information, the total number of words, and concision ratio (ratio between the information units and the total number of words).27,28

Metaphors (explanation and alternatives), Direct Speech Acts (DSA), and Indirect Speech Acts (ISA; explanation and alternatives), Linguistic and Emotional Prosody, and Narrative Discourse (partial retelling, total retelling, and full-text comprehension) make up the MEC. The MEC battery was administered, and performance was measured in accordance with the guidelines validated for the Brazilian population.29 The cutoff points were those suggested for the age-group 60–75 years, with adjustments for education: metaphors (2–7 years of education, 19 points; ≥8 years of schooling, 25 points), Direct and Indirect Speech (2–7 years of education, 26 points; ≥8 years of schooling, 27 points), Linguistic Prosody (2–7 years of education, 6 points; ≥9 years of schooling, 9 points), Emotional Prosody (2–7 years of education, 6 points; ≥8 years of schooling, 8 points), partial retelling (2–7 years of education, 5 points; ≥8 years of schooling, 11 points), complete retelling (2–7 years of schooling, 2 points; ≥8 years of schooling, 8 points), and full-text comprehension (2–7 years of education, 5 points; ≥8 years of schooling, 8 points).29,30

Multisensory and cognitive interventions

All subjects participated in the intervention program, which consisted of multisensory and cognitive activities designed for prevention of memory and language impairments. The intervention was organized as workshops for a group of ten or fewer volunteers. All sessions lasted 1 hour and were held twice a week, totaling 48 workshops. The workshops were based on a variety of recreational and ludic activities (eg, music, dance, singing, food preparation, and selecting pictures) designed to include a number of verbal, visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, and gustatory stimuli as motivational actions for systematic exercises of language and memory. Cognitive training was based on the act of speaking, social interactions between participants, and multisensory stimulation. Each workshop had diversified activities and goals (Table S2).

All group I participants were submitted to neuropsychological tests and to the intervention program on the environment of their own long-term-care institutions, in a quiet and well-lit room with similar physical conditions, and without interruptions. The NI group subjects were also tested and submitted to the intervention program, in public places for ludic and social activities in community centers for elderly. The experimenters were the same for all participants. Because the I group were assessed in their own institution, experimenters were not blind to the group of the participant.

Neuropsychological reassessment and monitoring during the intervention program

To compare cognitive performance at the different stages of the intervention between groups, MMSE and language tests were carried out in the beginning (before stimulation), in the middle (after 24 sessions), and at the end (after 48 sessions). Thus, all patients were cognitively reassessed every 3 months.

Statistical analysis

The cognitive statuses of the elderly groups attending the intervention program were assessed by MMSE and language-test scores. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) analysis was conducted: a 2 × 2 (group × number of sessions) as raw-change score = A – B, where A was “after” and B was baseline, or “before”. A main effect of the group variable would indicate greater improvement in one group versus the other, a main effect of the time-point variable would indicate a difference in improvement from baseline to 3 months and baseline to 6 months, and an interaction between group and time point variables would indicate differences in the amount of improvement across time in both groups. BioEstat version 5.0 (http://www.mamiraua.org.br) was used for statistical analysis of the data.31 Two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post tests were applied using Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) to measure possible interactions between lifestyles (I vs NI) and the number of sessions (24 vs 48) on the performance of neuropsychological tests.

Results

MMSE and language-test results

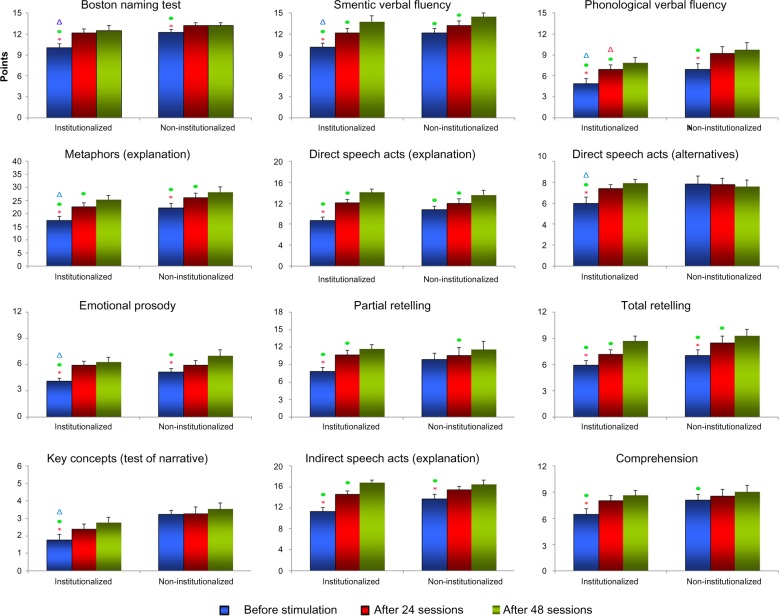

Statistical differences between the average MMSE scores were not significant, whereas in the language tests a number of significant differences were detected. Figure 1 gives graphical representations of mean scores and respective standard errors of neuropsychological tests indicating significant differences between time points (number of sessions) into the same group and between the same time points between groups. Note that before stimulation, the I group showed on average lower scores than the NI group in a number of tests: Boston Naming (I=10.1±0.58, NI=12.3±042 [mean ± standard error], Mann–Whitney Z[U]=2.72; P=0.007), SVF (I=10.1±0.64, NI=12.2±068, t=−2.15; P=0.04), PVF (I=4.92±0.72, NI=6.97±085, t=−2.83; P=0.007), key concepts (I=1.76±0.35, NI=3.24±023, Mann– Whitney Z[U]=2.96, P=0.003), metaphors – explanation (I=17.4±1.61, NI=22.24±1.86, t=−2.57; P=0.01), DSA – alternatives (I=6.00±0.58, NI=7.88±0.74, t=−2.39; P=0.022), and Emotional Prosody (I=4.12±0.33, NI=5.18±043, Mann– Whitney Z[U]=2.63, P=0.008). Cognitive and multisensory stimulation reduced the language differences between the I and NI groups to PVF after 24 sessions (I=6.94±0.71, NI=9.29±094, t=−2.77; P=0.0085), and after 48 sessions no language differences were detected anymore. Table S3 gives all mean scores and standard errors for the I and NI groups at all time points and tests where we detected statistically significant differences in the amount of improvement after the intervention program. Tables 1 and 2 show in detail t-tests or Mann–Whitney results inside each group and between groups before and after stimulation. Because the I group showed lower performance on the language tests before the stimulation, the amount of language improvement after stimulation was higher than in the NI group.

Figure 1.

Graphical representations of mean and standard error of tests scores in the institutionalized (I) and noninstitutionalized (NI) groups across time (number of sessions: 0, 24, 48) of elderly subjects. The mean and standard error values are indicated on the y-axis, and the number of sessions and groups are indicated on the x-axis.

Abbreviations: MMSE, mini-mental state examination; SVF, semantic verbal fluency; PVF, phonological verbal fluency; Expl, explanation; DSA, direct speech acts; ISA, indirect speech acts.

Table 1.

T-tests results with t- and P-values inside each group before and after stimulation

| Tests | Institutionalized

|

Noninstitutionalized

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before stimulation vs after 24 sessions | After 24 sessions vs after 48 sessions | Before stimulation vs after 48 sessions | Before stimulation vs after 24 sessions | After 24 sessions vs after 48 sessions | Before stimulation vs after 48 sessions | |

| Boston Naming | t=−6.0966 | – | t=−5.7469 | t=−4.0157 | – | t=−3.1168 |

| P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | P=0.001 | P=0.0066 | |||

| SVF | t=−9.4061 | t=−5.7162 | t=−12.959 | – | t=−2.3952 | t=−2.7531 |

| P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | P=0.0291 | P=0.0141 | ||

| PVF | t=−8.2193 | t=−3.1762 | t=−7.522 | t=−4.718 | – | t=−3.0514 |

| P<0.0001 | P=0.004 | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | P=0.0076 | ||

| Key concepts (test of narrative) | t=−2.179 | – | t=−3.3333 | – | – | – |

| P=0.0393 | P=0.0028 | |||||

| Metaphors (explanation) | t=−6.8446 | t=−3.3864 | t=−7.8527 | t=−3.3119 | t=−3.4136 | t=−4.3605 |

| P<0.0001 | P=0.0024 | P<0.0001 | P=0.0044 | P=0.0035 | P<0.0001 | |

| DSA (explanation) | t=−6.831 | t=−5.0761 | t=−10.453 | – | t=−2.2618 | t=−3.4267 |

| P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | P=0.0379 | P=0.0034 | ||

| DSA (alternatives) | t=−3.1569 | – | t=−3.9489 | – | – | – |

| P=0.0042 | P=0.0006 | |||||

| ISA (explanation) | t=−6.4679 | t=−4.9609 | t=−9.4186 | t=−3.1158 | – | t=−4.77 |

| P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | P=0.0066 | P<0.0001 | ||

| Emotional | t=−7.0081 | – | t=−5.4436 | – | t=−2.6648 | t=−2.3451 |

| Prosody | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | P=0.0169 | P=0.0322 | ||

| Partial retelling | t=−6.5338 | t=−2.522 | t=−6.0136 | – | t=−2.4874 | – |

| P<0.0001 | P=0.0187 | P<0.0001 | P=0.0242 | |||

| Total retelling | t=−2.8284 | t=−6.1954 | t=−4.9847 | t=−3.732 | t=−2.4245 | t=−4.4362 |

| P=0.0093 | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | P=0.0018 | P=0.0275 | P<0.0001 | |

| Comprehension | t=−3.9192 | – | t=−5.2553 | – | – | t=−2.3154 |

| P=0.0006 | P<0.0001 | P=0.0341 | ||||

Abbreviations: MMSE, mini-mental state examination; SVF, semantic verbal fluency; PVF, phonological verbal fluency; Expl, explanation; DSA, direct speech acts; ISA, indirect speech acts.

Table 2.

Institutionalized versus noninstitutionalized t- or Mann-Whitney test results, indicating significant differences between baseline, 24, and 48 sessions

| Tests | Institutionalized vs noninstitutionalized

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Before stimulation | After 24 sessions | After 48 sessions | |

| Boston Naming | Mann–Whitney Z(U)=2.7162 P=0.0066 |

– | – |

| SVF |

t=−2.1506 P=0.0375 |

– | – |

| PVF |

t=−2.8283 P=0.0073 |

t=−2.7709 P=0.0085 |

– |

| Key concepts (test of narrative) | Mann–Whitney Z(U)=2.9597 P=0.0031 |

– | – |

| Metaphors (explanation) |

t=−2.5675 P=0.0141 |

– | – |

| DSA (explanation) | – | – | – |

| DSA (alternatives) |

t=−2.3952 P=0.022 |

– | – |

| ISA (explanation) | – | – | – |

| Emotional | Mann–Whitney | – | – |

| Prosody |

Z(U)=2.6308 P=0.0085 |

||

| Partial retelling | – | – | – |

| Total retelling | – | – | – |

| Comprehension | – | – | – |

Abbreviations: MMSE, mini-mental state examination; SVF, semantic verbal fluency; PVF, phonological verbal fluency; Expl, explanation; DSA, direct speech acts; ISA, indirect speech acts.

Institutionalization and multisensory and cognitive stimulation

Two groups (NI and I) × two time points (number of sessions, 24 and 48) two-way ANOVA analysis as raw-change score = A – B, where A was “after” and B was baseline, or “before,” revealed group effects on performance in the following tests: Boston Naming (F1,80=13.13, P=0.0008), key concepts (F1,80=11.74, P=0.0011) from narrative, DSA – explanation (F1,80=4.47, P=0.03), and partial retelling (F1,80=4.76, P=0.0321) from the MEC battery. The number of sessions affected the performance of SVF (F1,80=30.54, P<0.0001) and PVF (F1,80=4.05, P=0.047) tests, and from the MEC battery the following tests: metaphors – explanation (F1,80=8.51, P=0.0046), DSA – explanation (F1,80=19.7, P<0.0001) and alternatives (F1,80=4.76, P=0.032), ISA – explanation (F1,80=22.73, P,0.0001), Emotional Prosody (F1,80=4.59, P=0.0352), and partial (F1,80=5.03, P=0.0276) and complete (F1,80=4.67, P=0.034) retelling and comprehension (F1,80=4.60, P=0.0350). The interactions between groups (NI and I) and number of sessions (0, 24, and 48) were not significant.

Discussion

This study investigated the impact of multisensory and cognitive stimulations on the scores of elderly subjects on MMSE and language tests. We also compared the test performance of the NI and I groups. The MMSE was used to select cognitively normal volunteers who subsequently underwent evaluations before and after multisensory and cognitive interventions. The two groups were matched for age and education. Both groups attended a series of 48 workshops involving multisensory and cognitive stimulation, and were evaluated before, during, and after the stimulation sessions ended. The results demonstrated that language tests were more sensitive than the classic screening test (MMSE) for detecting age-related cognitive decline and evaluating the cognitive progress. Previously,12 it was determined that I and NI groups differ in physical activity and performance on neuropsychological tests. In the present study, the I group showed worse cognitive performance when compared to the NI group, which may be due to a higher degree of sedentary lifestyle and poor cognitive stimulation. After the intervention program, we saw significant improvement in both groups, with the stimulation sessions having the greatest impact on the I group, whose improvement on cognitive tests showed no ceiling effect, as was observed for the NI group.

Age-related cognitive decline and an impoverished environment

Experimental data from rodents indicated there was cognitive decline in learning and memory that was associated with aging; in addition, these changes were related to structural and functional changes in hippocampal formation, which such functions depend on.32–34 Several experimental studies compared cognitive performance among animals living in an enriched environment and an impoverished environment for sensory input and motor activities. These studies found animals of the same genetic variety show hippocampal cognitive dysfunction after living in impoverished environments, with deficits in learning and spatial memory.35,36 An experimental study in mice conducted in our laboratory14 determined that mnemonic skills deteriorated more intensely with impaired spatial and episodic-like memories when the aging process occurred in an impoverished environment. Accordingly, older animals that were housed in the enriched environment showed preserved learning and memory in all tests, suggesting the mechanisms of consolidation and recovery for these types of memory were maintained by somatomotor and cognitive stimulations in the enriched condition. Another recent study tested how environmental enrichment can reverse the changes in spatial learning and memory that are impaired by advancing age in rats, concomitantly with neurogenesis. Although the performance of young rats overcame that of aged rats, aged rats exposed to enriched environments performed better in all behavioral measures than aged rats housed individually.37

The human cognitive decline associated with aging seems to be a consequence of neural network impairments,38–41 which is mainly associated with vascular,42,43 inflammatory,44–46 metabolic,47–49 and oxidative50,51 changes. These pathophysiological neural network changes are worsened by a sedentary lifestyle,52–54 and physical and cognitive stimulation on a regular basis seem to delay these damages in both healthy and demented older persons.55 In a recent review, Volkers and Scherder12 showed that sedentary and lonely elderly subjects living in long-term care institutions (impoverished conditions) had worse cognitive performance and cognitively decline more quickly than individuals who had active lives in the community with their families (enriched conditions). These authors demonstrated that institutionalization exacerbates the cognitive decline, probably due to the lower degree of cognitive and physical activities in these environments. Institutionalization is associated with excessive time in bed, and when out of bed, elderly persons remain inactive and passive. When using scales to assess the quality of life of the institutionalized elderly, there was greater impairment in the usual activities needed for daily living, and aggravating factors were anxiety, depression, and lack of family support.56 In this context, the reduced levels of physical and cognitive activities in the institutionalized environment favor cognitive decline, depression, and decreasing quality of life. The worse cognitive performance among the elderly in this study seems to be related to the impoverished environment of long-term-care institutions, which were improved by the implementation of workshops and multisensory stimulation. Therefore, we suggest the plasticity of the institutionalized elderly brain is preserved, and could be enhanced by regular cognitive and multisensory interventions.

Age-related cognitive decline and language neuropsychological tests

The decrease in language skills, in association with semantic memory, seems to be one of the first consequences of aging on cognitive performance, but is also seen in early stage Alzheimer’s disease.57 The impairment of semantic memory suggests there are neural compensation mechanisms, such as retrieving words integrated with visual information.58 In a recent study,59 Cotelli et al demonstrated that performance on tests of naming was associated with activation of the left frontal and temporal areas in both young and elderly subjects, but that this activity included the prefrontal cortex during normal aging, indicating the presence of pathological reorganization of these pathways during aging. Sugarman et al57 determined the naming test associated with functional magnetic resonance imaging has predictive value for the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and should be used as a presymptomatic biomarker, justifying our choice of using cognitive skill tests involving language functions. Other findings suggest similar sensitivities with tests of SVF, demonstrating that possible changes are relevant for the diagnosis of early cognitive decline and to measure its worsening.60 It has been proposed that the decrease in verbal working memory and reduced reading comprehension are early indicators of aging cognitive decline,61 and that patients in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease exhibit language deficits that are expressed as a reduction in syntactic complexity,62 using the analysis of language elicited from the Cookie Theft concept. This test requires the participant to describe what is happening in the picture. The verbal description of the figure was recorded and then transcribed from the MP3 file, following standard procedures.63 In this study, we employed the Cookie Theft narrative test and evaluated a series of linguistic functions. We found that three of four indicators improved after multisensory and cognitive stimulation, namely key concepts, narrative efficiency, and information units, and this effect was significantly greater in the I group. These findings confirmed the importance of our choice to assess language disorders associated with age-related cognitive decline that are aggravated by the deleterious effects of the impoverished environment of long-term-care institutions.

Beneficial implications of a multisensory and cognitive stimulation intervention program for the institutionalized elderly

The set of data obtained here in healthy aging subjects, and findings from other studies in both healthy and demented elderly subjects, demonstrate it is possible to improve cognitive55,64–66 and perceptual67–70 functions through training and exercises that make up sensory/motor and cognitive-oriented stimulation programs for the elderly. As recommended elsewhere,71,72 our intervention program was designed to take advantage of presumed compensatory mechanisms associated with multisensory/motor and cognitive stimulation, thereby limiting functional decline in higher cognitive performance in aging people. However, a previous report73 found that cognitive stimulation programs differ in duration, strategies, and the methods employed; therefore, there are widely diverse effects and maintenance of long-term results.

Another important finding was that the NI persons submitted to our interventional program showed less increase in neuropsychological tests performance than the I group. We suggest that the enriched environment interactions and socialization in the community lifestyles of the NI group exposed these subjects to a greater amount of cognitive and multisensory stimulation, decreasing the magnitude of the effects of therapeutic sessions. In line with these findings, other studies suggest that elderly subjects without any concomitant cognitive stimulation may benefit relatively more from training than older people with parallel cognitive stimulation.74 However, it is necessary to consider that since there was no comparison with a “no intervention” control group, it is impossible to distinguish any improvements from a practice effect, but because a possible practice effect would be present in both groups, it is reasonable to suppose that this practice effect would not explain significant differences between the I and NI groups.

Supplementary materials

Table S1.

Language test details

| Objectives | Command | Score and cutoff | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boston Naming Test | To assess the ability of naming by visual confrontation. | The patient must name 15 figures submitted to him/her. Each correct answer corresponds to 1 point. |

Cutoff equivalent to 12 out of 15 possible figures named correctly. |

| Semantic (SVF) and Phonological (PVF) Verbal Fluencies | To evaluate language production, starting with triggers of semantic categories and phonemes. | The patient has to say as many words as possible in 1 minute in the categories animals and fruits for semantic verbal fluency, and say as many words as possible beginning with A and F for phonological verbal fluency. All correct words are scored within the categories analyzed. | <9 points for illiterates, <12 points for 1–7 years of schooling, and <13 points for individuals with 8 years or more of schooling. |

| Test of Narrative “Cookie Theft” | Assess the skills of narrating and describing. To analyze the production of oral language before exposure to the figure “Cookie Theft”. | The volunteer is instructed to describe everything he is seeing in the image in the best way possible. The speech is recorded, transcribed, and analyzed. |

Test results were evaluated using previous published criteria on the information content of the image, including the number of key concepts, narrative efficiency, number of units of information, the total number of words, and concision ratio (ratio between the information units and the total number of words). |

| MEC battery | |||

| Metaphors (explanation and alternatives) | Assess the ability to understand and explain the nonliteral sense of sentences. | The individual is asked to explain the meaning of the sentence in their own words. The answer is scored with 0, 1, or 2, with a maximum score of 40 points. After this step, three sentences are read in a loud voice, and the volunteer has to indicate which one of the three sentences best explains the meaning of the sentence he had explained. | 2–7 years of education, 19 points; ≥8 years of schooling, 25 points. |

| Direct (DSA) and Indirect (ISA) Speech Acts(explanation and alternatives) |

Examine the ability to understand direct speech acts (10 situations in which the speaker means literally what is said) and indirect (10 cases in which the intention of the speaker is not explicit and must be inferred from the context), both from a particular communicative context. | The subject is asked to explain in his or her own words what the person meant after hearing the situation read by the examiner. The explanation is scored 0, 1, or 2, with a maximum score of 40 points. After the explanation, the volunteer is asked to choose an alternative that better explains what the phrase meant. | 2–7 years of education, 26 points; ≥8 years of schooling, 27 points. |

| Linguistic Prosody | Evaluate the perception and identification of linguistic intonation patterns. | Each sentence was previously recorded on audio equipment, with adjustable accents for the region in three different intonations (affirmative, interrogative, and imperative). A total of 12 sentences were read in random order. The subject is asked to identify the intonation. The maximum score is 12 points. |

2–7 years of education, 6 points; ≥9 years of schooling, 9 points. |

| Emotional Prosody | Evaluate the ability to perceive and identify emotional intonation patterns. | Each sentence was previously recorded on audio equipment, with adjustable regional accent in three different emotional intonations (happiness, sadness, and anger), making 12 stimuli, presented in random order. The evaluated individual was asked to identify the intonation. The maximum score was 12 points. | 2–7 years of education, 6 points; ≥8 years of schooling, 8 points. |

| Narrative discourse | |||

| 1. Partial retelling | Evaluate comprehension and recall of complex linguistic information, as well as the ability to examine. | After reading each paragraph, the subject was asked to recount with his own words the paragraph read. Total score for essential information was 18 points. |

2–7 years of education, 5 points; ≥8 years of schooling, 11 points. |

| 2. Complete retelling | discursive expression. | The same story is read a second time, in its entirety, by the examiner. The individual being evaluated is instructed to retell after reading, in his or her own words, the whole story. The information in the narrative was scored by comparison with a grid of 13 main information points, generating a maximum score of 13 points. |

2–7 years of schooling, 2 points;≥8 years of schooling, 8 points. |

| 3. Comprehension | Examines the understanding of the same story through 12 issues of short answers. Each correct answer adds 1 point, the maximum score is 12 points. | 2–7 years of education, 5 points;≥8 years of schooling, 8 points. |

Table S2.

Detailed organization of the workshops for multisensory and cognitive stimulation

| Workshops | Stimuli | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| First series of workshops | ||

| 1st | Autobiographical memory | Recalling events of their personal lives. |

| 2nd, 3rd | Attention | Stimuli through the techniques of attention in a group. |

| 4th, 5th | Phonological and semantic | Activation of phonological and semantic networks of language through double-bingo lotto for semantic category and phoneme. |

| 6th, 7th | Phonological and semantic | Bingo lotto of letters where networking phonological and syntactic language are activated through the bingo cartouches. |

| 8th, 9th | Syntax | List of words containing nouns and verbs: the group had to identify and transform the names into verbs and verbs into names, explaining their meaning, providing a synonym and elaborating phrases. |

| 10th, 11th | Prospective memory | Thematic workshops: politics, health, education, public safety, etc. Personal positioning. |

| 12th–15th | Sound, music and discourse | Use of sound and music: music competition, identification of sounds and their representations, their music, and lyrics. |

| 16th–19th | Sound and motor | Use of sound stimuli and motor activities associated with body movements. Dance videos, identifying the movements and rhythm. Free dance. |

| 20th, 21st | Tactile and discursive | Tactile stimuli blindfolded identification of objects and their function, surface sensitivity. |

| 22nd–24th | Olfactory, gustatory, and discursive | Olfactory and gustatory stimuli, identification of odors and flavors and their representations, exchange recipes and tasting. |

| Second series of workshops | ||

| 25th–30th | Visual and discursive | Use of images, pictures, and photos as triggers for speech, pairing visual and verbal information. |

| 31st, 32nd | Semantic memory | Working with the categorization and association intruders. |

| 33rd, 34th | Language comprehension | Activities with proverbs and popular sayings. Task working words and phrases with double meanings. |

| 35th, 36th | Memory and discourse | Folk legends and popular beliefs, personal accounts through evocations of the subject. |

| 37th–40th | Facial expression | Identification and categorization of facial expressions, context of facial expressions, creating a context for the emotions, execution and guesswork of facial expressions. |

| 41st, 42nd | Emotional prosody | Analysis of the voice on the emotions, relate them to situations and categorize them in corresponding emotions, interpretation of dialogues with different intonations. |

| 43rd | Linguistic prosody | Analysis of speech situations (statement, exclamation mark), interpretation and creation of dialogues. |

| 44th, 45th | Narrative | Narration and creating stories. |

| 46th, 47th | Retelling | Retelling a story with as much detail as possible, intervening in memory and comprehension of texts and stories. |

| 48th | Narrative and retelling | Evocation of the intervention program highlights and closure. |

Table S3.

Mean scores and standard errors for language tests from institutionalized and noninstitutionalized groups with significant differences

| Tests | Institutionalized

|

Noninstitutionalized

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before stimulation | After 24 sessions | After 48 sessions | Before stimulation | After 24 sessions | After 48 sessions | |

| Boston Naming | 10.1±0.5829 | 12.2±0.5935 | 12.5±0.6979 | 12.3±0.418 | 13.2±0.407 | 13.3±0.4091 |

| SVF | 10.1±0.6372 | 12.2±0.6589 | 13.8±0.7869 | 12.2±0.6819 | 13.3±0.5753 | 14.4±0.6818 |

| PVF | 4.92±0.7192 | 6.94±0.7132 | 7.86±0.8229 | 6.97±0.8461 | 9.29±0.9404 | 9.70±1.0788 |

| Key concepts (test of narrative) | 1.76±0.3478 | 2.4±0.2828 | 2.76±0.307 | 3.24±0.2353 | 3.29±0.3614 | 3.53±0.3548 |

| Metaphors (explanation) | 17.4±1.6093 | 22.68±1.5671 | 25.44±1.6218 | 22.24±1.862 | 26.12±1.8882 | 28.18±2.0477 |

| DSA (explanation) | 8.72±0.6941 | 12.16±0.665 | 14.08±0.6243 | 10.82±0.6655 | 12.00±0.8911 | 13.59±0.9278 |

| DSA (alternatives) | 6.00±0.5831 | 7.40±0.3873 | 7.92±0.3693 | 7.88±0.7371 | 7.82±0.6017 | 7.59±0.6477 |

| ISA (explanation) | 11.40±0.7461 | 14.64±0.658 | 16.84±0.4785 | 13.76±0.8381 | 15.47±0.6593 | 16.47±0.8407 |

| Emotional Prosody | 4.12±0.3282 | 5.96±0.4564 | 6.32±0.5407 | 5.18±0.4308 | 5.94±0.5249 | 7.00±0.7276 |

| Partial retelling | 7.92±0.6555 | 10.76±0.7556 | 11.68±0.7432 | 9.94±1.0896 | 10.65±1.3878 | 11.59±1.4629 |

| Total retelling | 6.00±0.5 | 7.20±0.5477 | 8.68±0.5936 | 7.06±0.6444 | 8.53±0.7579 | 9.29±0.7848 |

| Comprehension | 6.48±0.6883 | 8.08±0.5713 | 8.64±0.5594 | 8.12±0.6907 | 8.59±0.8047 | 9.06±0.74 |

Abbreviations: MMSE, mini-mental state examination; SVF, semantic verbal fluency; PVF, phonological verbal fluency; Expl, explanation; DSA, direct speech acts; ISA, indirect speech acts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Programa Pesquisa para o SUS: Gestão Compartilhada em Saúde (PPSUS) – Ministério da Saúde/Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq)/Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Pará (FAPESPA)/Secretaria de Saúde do Estado do Pará (SESPA) (grants 051/2007 and 013/2009); Agência Brasileira da Inovação (FINEP)/Fundação de Amparo e Desenvolvimento da Pesquisa (FADESP) (grant 01.04.0043.00); and Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa (PROPESP-UFPA)/Fundação de Amparo e Desenvolvimento da Pesquisa (FADESP).

Footnotes

Author contributions

TCGO, FCS, NVOBT, and CWPD designed the study and participated in the experimental design. TCGO, FCS, and LDDM performed the experiments. TCGO, NVOBT, and CWPD participated in the data analysis and organized the manuscript draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Brooks-Wilson AR. Genetics of healthy aging and longevity. Hum Genet. 2013;132(12):1323–1338. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1342-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin SL, Hardy TM, Tollefsbol TO. Medicinal chemistry of the epigenetic diet and caloric restriction. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20(32):4050–4059. doi: 10.2174/09298673113209990189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayissi VB, Ebrahimi A, Schluesenner H.Epigenetic effects of natural polyphenols: a focus on SIRT1-mediated mechanisms Mol Nutr Food ResEpub July232013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Johansson A, Enroth S, Gyllensten U. Continuous aging of the human DNA methylome throughout the human lifespan. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lovden M, Xu W, Wang HX. Lifestyle change and the prevention of cognitive decline and dementia: what is the evidence? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(3):239–243. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835f4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Assar M, Angulo J, Rodríguez-Mañas L. Oxidative stress and vascular inflammation in aging. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;65C:380–401. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander GE, Ryan L, Bowers D, et al. Characterizing cognitive aging in humans with links to animal models. Front Aging Neurosci. 2012;4:21. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2012.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke SN, Ryan L, Barnes CA. Characterizing cognitive aging of recognition memory and related processes in animal models and in humans. Front Aging Neurosci. 2012;4:15. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2012.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyndall AV, Davenport MH, Wilson BJ, et al. The brain-in-motion study: effect of a 6-month aerobic exercise intervention on cerebrovascular regulation and cognitive function in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erickson KI, Weinstein AM, Lopez OL. Physical activity, brain plasticity, and Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Med Res. 2012;43(8):615–621. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Small BJ, Dixon RA, McArdle JJ, Grimm KJ. Do changes in lifestyle engagement moderate cognitive decline in normal aging? Evidence from the Victoria Longitudinal Study. Neuropsychology. 2012;26(2):144–155. doi: 10.1037/a0026579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Volkers KM, Scherder EJ. Impoverished environment, cognition, aging and dementia. Rev Neurosci. 2011;22(3):259–266. doi: 10.1515/RNS.2011.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zalik E, Zalar B. Differences in mood between elderly persons living in different residential environments in Slovenia. Psychiatr Danub. 2013;25(1):40–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diniz D, Foro CA, Rego CM, et al. Environmental impoverishment and aging alter object recognition, spatial learning, and dentate gyrus astrocytes. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32(3):509–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woods B, Aguirre E, Spector AE, Orrell M. Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD005562. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005562.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salotti P, De Sanctis B, Clementi A, Fernandez Ferreira M, De Silvestris T. Evaluation of the efficacy of a cognitive rehabilitation treatment on a group of Alzheimer’s patients with moderate cognitive impairment: a pilot study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2013;25(4):403–409. doi: 10.1007/s40520-013-0062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma S, Rakoczy S, Brown-Borg H. Assessment of spatial memory in mice. Life Sci. 2010;87(17–18):521–536. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dere E, Huston JP, De Souza Silva MA. Episodic-like memory in mice: simultaneous assessment of object, place and temporal order memory. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 2005;16(1–3):10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresprot.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwok T, Wong A, Chan G, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive training for Chinese elderly in Hong Kong. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:213–219. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S38070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kattenstroth JC, Kalisch T, Holt S, Tegenthoff M, Dinse HR. Six months of dance intervention enhances postural, sensorimotor, and cognitive performance in elderly without affecting cardio-respiratory functions. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:5. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alain C, Zendel BR, Hutka S, Bidelman GM.Turning down the noise: the benefit of musical training on the aging auditory brain Hear ResEpub July22013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Ardila A, Rosselli M. Spontaneous language production and aging: sex and educational effects. Int J Neurosci. 1996;87(1–2):71–78. doi: 10.3109/00207459608990754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertolucci PH, Brucki SM, Campacci SR, Juliano Y. The Mini-Mental State Examination in a general population: impact of educational status. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1994;52(1):1–7. Portuguese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bertolucci PH, Okamoto IH, Toniolo JN, Ramos LR, Bruki SM. Desempenho da população brasileira na bateria neuropsicológica do Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Rev Psiquiatr Clin. 1998;25:80–83. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertolucci PH, Okamoto IH, Brucki SM, Siviero MO, Toniolo Neto J, Ramos LR. Applicability of the CERAD neuropsychological battery to Brazilian elderly. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2001;59(3-A):532–536. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2001000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caramelli P, Carthery-Goulart MT, Porto CS, Charchat-Fichman H, Nitrini R. Category fluency as a screening test for Alzheimer disease in illiterate and literate patients. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(1):65–67. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31802f244f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forbes-McKay KE, Venneri A. Detecting subtle spontaneous language decline in early Alzheimer’s disease with a picture description task. Neurol Sci. 2005;26(4):243–254. doi: 10.1007/s10072-005-0467-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Groves-Wright K, Neils-Strunjas J, Burnett R, O’Neill MJ. A comparison of verbal and written language in Alzheimer’s disease. J Commun Disord. 2004;37(2):109–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fonseca RP, Joanette Y, Côté H, et al. Brazilian version of the Protocole Montreal d’Evaluation de la Communication (Protocole MEC): normative and reliability data. Span J Psychol. 2008;11(2):678–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fonseca RP, Parente MA, Côté H, Ska B, Joanette Y. Introducing a communication assessment tool to Brazilian speech therapists: the MAC Battery. Pro Fono. 2008;20(4):285–291. doi: 10.1590/s0104-56872008000400014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ayres M, M AJ, Ayres D, Santos AS. BioEstat 5.0: Aplicações Estatísticas nas Areas das Ciências Biológicas e Médicas [BioEstat 5.0: Statistical applications in the Biological and Medical Sciences] Belém, Brazil: Sociedade Civil Mamirauá; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teather LA, Magnusson JE, Chow CM, Wurtman RJ. Environmental conditions influence hippocampus-dependent behaviours and brain levels of amyloid precursor protein in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16(12):2405–2415. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frick KM, Fernandez SM. Enrichment enhances spatial memory and increases synaptophysin levels in aged female mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(4):615–626. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenzweig ES, Barnes CA. Impact of aging on hippocampal function: plasticity, network dynamics, and cognition. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;69(3):143–179. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teather LA, Wurtman RJ. Dietary CDP-choline supplementation prevents memory impairment caused by impoverished environmental conditions in rats. Learn Mem. 2005;12(1):39–43. doi: 10.1101/lm.83905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iso H, Simoda S, Matsuyama T. Environmental change during postnatal development alters behaviour, cognitions and neurogenesis of mice. Behav Brain Res. 2007;179(1):90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Speisman RB, Kumar A, Rani A, et al. Environmental enrichment restores neurogenesis and rapid acquisition in aged rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(1):263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Onoda K, Ishihara M, Yamaguchi S. Decreased functional connectivity by aging is associated with cognitive decline. J Cogn Neurosci. 2012;24(11):2186–2198. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalkstein J, Checksfield K, Bollinger J, Gazzaley A. Diminished top-down control underlies a visual imagery deficit in normal aging. J Neurosci. 2011;31(44):15768–15774. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3209-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gluck MA, Myers CE, Nicolle MM, Johnson S. Computational models of the hippocampal region: implications for prediction of risk for Alzheimer’s disease in non-demented elderly. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2006;3(3):247–257. doi: 10.2174/156720506777632826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salami A, Eriksson J, Nyberg L. Opposing effects of aging on large-scale brain systems for memory encoding and cognitive control. J Neurosci. 2012;32(31):10749–10757. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0278-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jellinger KA. Pathology and pathogenesis of vascular cognitive impairment – a critical update. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:17. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henry-Feugeas MC, Koskas P. Cerebral vascular aging: extending the concept of pulse wave encephalopathy through capillaries to the cerebral veins. Curr Aging Sci. 2012;5(2):157–167. doi: 10.2174/1874609811205020157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sama DM, Norris CM. Calcium dysregulation and neuroinflammation: discrete and integrated mechanisms for age-related synaptic dysfunction. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(4):982–995. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keleshian VL, Modi HR, Rapoport SI, Rao JS. Aging is associated with altered inflammatory, arachidonic acid cascade, and synaptic markers, influenced by epigenetic modifications, in the human frontal cortex. J Neurochem. 2013;125(1):63–73. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 46.Varnum MM, Ikezu T. The classification of microglial activation phenotypes on neurodegeneration and regeneration in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2012;60(4):251–266. doi: 10.1007/s00005-012-0181-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Craft S, Foster TC, Landfield PW, Maier SF, Resnick SM, Yaffe K. Session III: Mechanisms of age-related cognitive change and targets for intervention: inflammatory, oxidative, and metabolic processes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(7):754–759. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Birdsill AC, Carlsson CM, Willette AA, et al. Low cerebral blood flow is associated with lower memory function in metabolic syndrome. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21(7):1313–1320. doi: 10.1002/oby.20170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anton S, Leeuwenburgh C. Fasting or caloric restriction for healthy aging. Exp Gerontol. 2013;48(10):1003–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flynn JM, Melov S. SOD2 in mitochondrial dysfunction and neurode-generation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;62:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson EJ, Vishwanathan R, Johnson MA, et al. Relationship between serum and brain carotenoids, alpha-tocopherol, and retinol concentrations and cognitive performance in the oldest old from the Georgia Centenarian Study. J Aging Res. 2013;2013:951786. doi: 10.1155/2013/951786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ballesteros S, Mayas J, Reales JM. Does a physically active lifestyle attenuate decline in all cognitive functions in old age? Curr Aging Sci. 2013;6(2):189–198. doi: 10.2174/18746098112059990001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nemati Karimooy H, Hosseini M, Nemati M, Esmaily HO. Lifelong physical activity affects mini mental state exam scores in individuals over 55 years of age. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2012;16(2):230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takata Y, Ansai T, Soh I, et al. Physical fitness and cognitive function in an 85-year-old community-dwelling population. Gerontology. 2008;54(6):354–360. doi: 10.1159/000129757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng ST, Chow PK, Song YQ, et al. Mental and physical activities delay cognitive decline in older persons with dementia\Am J Geriatr PsychiatryEpub February62013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Estrada A, Cardona D, Segura AM, Chavarriaga LM, Ordonez J, Osorio JJ. Quality of life in institutionalized elderly people of Medellín. Biomedica. 2011;31(4):492–502. doi: 10.1590/S0120-41572011000400004. [Spanish] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sugarman MA, Woodard JL, Nielson KA, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of semantic memory as a presymptomatic biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease risk. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822(3):442–456. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wierenga CE, Stricker NH, McCauley A, et al. Altered brain response for semantic knowledge in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(3):392–404. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cotelli M, Manenti R, Brambilla M, Zanetti O, Miniussi C. Naming ability changes in physiological and pathological aging. Front Neurosci. 2012;6:120. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hall JR, Harvey M, Vo HT, O’Bryant SE. Performance on a measure of category fluency in cognitively impaired elderly. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2011;18(3):353–361. doi: 10.1080/13825585.2011.557495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.DeDe G, Caplan D, Kemtes K, Waters G. The relationship between age, verbal working memory, and language comprehension. Psychol Aging. 2004;19(4):601–616. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ahmed S, de Jager CA, Haigh AM, Garrard P. Logopenic aphasia in Alzheimer’s disease: clinical variant or clinical feature? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(11):1056–1062. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garrard P, Haigh AM, de Jager CA. Techniques for transcribers: assessing and improving consistency in transcripts of spoken language. Lit Linguist Comput. 2011;26(4):371–388. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fitzsimmons S, Buettner LL. Therapeutic recreation interventions for need-driven dementia-compromised behaviors in community-dwelling elders. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2002;17(6):367–381. doi: 10.1177/153331750201700603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park DC, Bischof GN. The aging mind: neuroplasticity in response to cognitive training. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2013;15(1):109–119. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.1/dpark. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruthirakuhan M, Luedke AC, Tam A, Goel A, Kurji A, Garcia A. Use of physical and intellectual activities and socialization in the management of cognitive decline of aging and in dementia: a review. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:384875. doi: 10.1155/2012/384875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Legault I, Faubert J. Perceptual-cognitive training improves biological motion perception: evidence for transferability of training in healthy aging. Neuroreport. 2012;23(8):469–473. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328353e48a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Legault I, Allard R, Faubert J. Healthy older observers show equivalent perceptual-cognitive training benefits to young adults for multiple object tracking. Front Psychol. 2013;4:323. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bower JD, Andersen GJ. Aging, perceptual learning, and changes in efficiency of motion processing. Vision Res. 2012;61:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bower JD, Watanabe T, Andersen GJ. Perceptual learning and aging: improved performance for low-contrast motion discrimination. Front Psychol. 2013;4:66. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kraft E. Cognitive function, physical activity, and aging: possible biological links and implications for multimodal interventions. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2012;19(1–2):248–263. doi: 10.1080/13825585.2011.645010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thom JM, Clare L. Rationale for combined exercise and cognition-focused interventions to improve functional independence in people with dementia. Gerontology. 2011;57(3):265–275. doi: 10.1159/000322198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kolanowski A, Buettner L. Prescribing activities that engage passive residents. An innovative method. J Gerontol Nurs. 2008;34(1):13–18. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20080101-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kwok TC, Chau WW, Yuen KS, et al. Who would benefit from memory training? A pilot study examining the ceiling effect of concurrent cognitive stimulation. Clin Interv Aging. 2011;6:83–88. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S16802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Language test details

| Objectives | Command | Score and cutoff | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boston Naming Test | To assess the ability of naming by visual confrontation. | The patient must name 15 figures submitted to him/her. Each correct answer corresponds to 1 point. |

Cutoff equivalent to 12 out of 15 possible figures named correctly. |

| Semantic (SVF) and Phonological (PVF) Verbal Fluencies | To evaluate language production, starting with triggers of semantic categories and phonemes. | The patient has to say as many words as possible in 1 minute in the categories animals and fruits for semantic verbal fluency, and say as many words as possible beginning with A and F for phonological verbal fluency. All correct words are scored within the categories analyzed. | <9 points for illiterates, <12 points for 1–7 years of schooling, and <13 points for individuals with 8 years or more of schooling. |

| Test of Narrative “Cookie Theft” | Assess the skills of narrating and describing. To analyze the production of oral language before exposure to the figure “Cookie Theft”. | The volunteer is instructed to describe everything he is seeing in the image in the best way possible. The speech is recorded, transcribed, and analyzed. |

Test results were evaluated using previous published criteria on the information content of the image, including the number of key concepts, narrative efficiency, number of units of information, the total number of words, and concision ratio (ratio between the information units and the total number of words). |

| MEC battery | |||

| Metaphors (explanation and alternatives) | Assess the ability to understand and explain the nonliteral sense of sentences. | The individual is asked to explain the meaning of the sentence in their own words. The answer is scored with 0, 1, or 2, with a maximum score of 40 points. After this step, three sentences are read in a loud voice, and the volunteer has to indicate which one of the three sentences best explains the meaning of the sentence he had explained. | 2–7 years of education, 19 points; ≥8 years of schooling, 25 points. |

| Direct (DSA) and Indirect (ISA) Speech Acts(explanation and alternatives) |

Examine the ability to understand direct speech acts (10 situations in which the speaker means literally what is said) and indirect (10 cases in which the intention of the speaker is not explicit and must be inferred from the context), both from a particular communicative context. | The subject is asked to explain in his or her own words what the person meant after hearing the situation read by the examiner. The explanation is scored 0, 1, or 2, with a maximum score of 40 points. After the explanation, the volunteer is asked to choose an alternative that better explains what the phrase meant. | 2–7 years of education, 26 points; ≥8 years of schooling, 27 points. |

| Linguistic Prosody | Evaluate the perception and identification of linguistic intonation patterns. | Each sentence was previously recorded on audio equipment, with adjustable accents for the region in three different intonations (affirmative, interrogative, and imperative). A total of 12 sentences were read in random order. The subject is asked to identify the intonation. The maximum score is 12 points. |

2–7 years of education, 6 points; ≥9 years of schooling, 9 points. |

| Emotional Prosody | Evaluate the ability to perceive and identify emotional intonation patterns. | Each sentence was previously recorded on audio equipment, with adjustable regional accent in three different emotional intonations (happiness, sadness, and anger), making 12 stimuli, presented in random order. The evaluated individual was asked to identify the intonation. The maximum score was 12 points. | 2–7 years of education, 6 points; ≥8 years of schooling, 8 points. |

| Narrative discourse | |||

| 1. Partial retelling | Evaluate comprehension and recall of complex linguistic information, as well as the ability to examine. | After reading each paragraph, the subject was asked to recount with his own words the paragraph read. Total score for essential information was 18 points. |

2–7 years of education, 5 points; ≥8 years of schooling, 11 points. |

| 2. Complete retelling | discursive expression. | The same story is read a second time, in its entirety, by the examiner. The individual being evaluated is instructed to retell after reading, in his or her own words, the whole story. The information in the narrative was scored by comparison with a grid of 13 main information points, generating a maximum score of 13 points. |

2–7 years of schooling, 2 points;≥8 years of schooling, 8 points. |

| 3. Comprehension | Examines the understanding of the same story through 12 issues of short answers. Each correct answer adds 1 point, the maximum score is 12 points. | 2–7 years of education, 5 points;≥8 years of schooling, 8 points. |

Table S2.

Detailed organization of the workshops for multisensory and cognitive stimulation

| Workshops | Stimuli | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| First series of workshops | ||

| 1st | Autobiographical memory | Recalling events of their personal lives. |

| 2nd, 3rd | Attention | Stimuli through the techniques of attention in a group. |

| 4th, 5th | Phonological and semantic | Activation of phonological and semantic networks of language through double-bingo lotto for semantic category and phoneme. |

| 6th, 7th | Phonological and semantic | Bingo lotto of letters where networking phonological and syntactic language are activated through the bingo cartouches. |

| 8th, 9th | Syntax | List of words containing nouns and verbs: the group had to identify and transform the names into verbs and verbs into names, explaining their meaning, providing a synonym and elaborating phrases. |

| 10th, 11th | Prospective memory | Thematic workshops: politics, health, education, public safety, etc. Personal positioning. |

| 12th–15th | Sound, music and discourse | Use of sound and music: music competition, identification of sounds and their representations, their music, and lyrics. |

| 16th–19th | Sound and motor | Use of sound stimuli and motor activities associated with body movements. Dance videos, identifying the movements and rhythm. Free dance. |

| 20th, 21st | Tactile and discursive | Tactile stimuli blindfolded identification of objects and their function, surface sensitivity. |

| 22nd–24th | Olfactory, gustatory, and discursive | Olfactory and gustatory stimuli, identification of odors and flavors and their representations, exchange recipes and tasting. |

| Second series of workshops | ||

| 25th–30th | Visual and discursive | Use of images, pictures, and photos as triggers for speech, pairing visual and verbal information. |

| 31st, 32nd | Semantic memory | Working with the categorization and association intruders. |

| 33rd, 34th | Language comprehension | Activities with proverbs and popular sayings. Task working words and phrases with double meanings. |

| 35th, 36th | Memory and discourse | Folk legends and popular beliefs, personal accounts through evocations of the subject. |

| 37th–40th | Facial expression | Identification and categorization of facial expressions, context of facial expressions, creating a context for the emotions, execution and guesswork of facial expressions. |

| 41st, 42nd | Emotional prosody | Analysis of the voice on the emotions, relate them to situations and categorize them in corresponding emotions, interpretation of dialogues with different intonations. |

| 43rd | Linguistic prosody | Analysis of speech situations (statement, exclamation mark), interpretation and creation of dialogues. |

| 44th, 45th | Narrative | Narration and creating stories. |

| 46th, 47th | Retelling | Retelling a story with as much detail as possible, intervening in memory and comprehension of texts and stories. |

| 48th | Narrative and retelling | Evocation of the intervention program highlights and closure. |

Table S3.

Mean scores and standard errors for language tests from institutionalized and noninstitutionalized groups with significant differences

| Tests | Institutionalized

|

Noninstitutionalized

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before stimulation | After 24 sessions | After 48 sessions | Before stimulation | After 24 sessions | After 48 sessions | |

| Boston Naming | 10.1±0.5829 | 12.2±0.5935 | 12.5±0.6979 | 12.3±0.418 | 13.2±0.407 | 13.3±0.4091 |

| SVF | 10.1±0.6372 | 12.2±0.6589 | 13.8±0.7869 | 12.2±0.6819 | 13.3±0.5753 | 14.4±0.6818 |

| PVF | 4.92±0.7192 | 6.94±0.7132 | 7.86±0.8229 | 6.97±0.8461 | 9.29±0.9404 | 9.70±1.0788 |

| Key concepts (test of narrative) | 1.76±0.3478 | 2.4±0.2828 | 2.76±0.307 | 3.24±0.2353 | 3.29±0.3614 | 3.53±0.3548 |

| Metaphors (explanation) | 17.4±1.6093 | 22.68±1.5671 | 25.44±1.6218 | 22.24±1.862 | 26.12±1.8882 | 28.18±2.0477 |

| DSA (explanation) | 8.72±0.6941 | 12.16±0.665 | 14.08±0.6243 | 10.82±0.6655 | 12.00±0.8911 | 13.59±0.9278 |

| DSA (alternatives) | 6.00±0.5831 | 7.40±0.3873 | 7.92±0.3693 | 7.88±0.7371 | 7.82±0.6017 | 7.59±0.6477 |

| ISA (explanation) | 11.40±0.7461 | 14.64±0.658 | 16.84±0.4785 | 13.76±0.8381 | 15.47±0.6593 | 16.47±0.8407 |

| Emotional Prosody | 4.12±0.3282 | 5.96±0.4564 | 6.32±0.5407 | 5.18±0.4308 | 5.94±0.5249 | 7.00±0.7276 |

| Partial retelling | 7.92±0.6555 | 10.76±0.7556 | 11.68±0.7432 | 9.94±1.0896 | 10.65±1.3878 | 11.59±1.4629 |

| Total retelling | 6.00±0.5 | 7.20±0.5477 | 8.68±0.5936 | 7.06±0.6444 | 8.53±0.7579 | 9.29±0.7848 |

| Comprehension | 6.48±0.6883 | 8.08±0.5713 | 8.64±0.5594 | 8.12±0.6907 | 8.59±0.8047 | 9.06±0.74 |

Abbreviations: MMSE, mini-mental state examination; SVF, semantic verbal fluency; PVF, phonological verbal fluency; Expl, explanation; DSA, direct speech acts; ISA, indirect speech acts.