Abstract

Objective To determine the association between concentration of prostate specific antigen (PSA) at age 40-55 and subsequent risk of prostate cancer metastasis and mortality in an unscreened population to evaluate when to start screening for prostate cancer and whether rescreening could be risk stratified.

Design Case-control study with 1:3 matching nested within a highly representative population based cohort study.

Setting Malmö Preventive Project, Sweden.

Participants 21 277 Swedish men aged 27-52 (74% of the eligible population) who provided blood at baseline in 1974-84, and 4922 men invited to provide a second sample six years later. Rates of PSA testing remained extremely low during median follow-up of 27 years.

Main outcome measures Metastasis or death from prostate cancer ascertained by review of case notes.

Results Risk of death from prostate cancer was associated with baseline PSA: 44% (95% confidence interval 34% to 53%) of deaths occurred in men with a PSA concentration in the highest 10th of the distribution of concentrations at age 45-49 (≥1.6 µg/L), with a similar proportion for the highest 10th at age 51-55 (≥2.4 µg/L: 44%, 32% to 56%). Although a 25-30 year risk of prostate cancer metastasis could not be ruled out by concentrations below the median at age 45-49 (0.68 µg/L) or 51-55 (0.85 µg/L), the 15 year risk remained low at 0.09% (0.03% to 0.23%) at age 45-49 and 0.28% (0.11% to 0.66%) at age 51-55, suggesting that longer intervals between screening would be appropriate in this group.

Conclusion Measurement of PSA concentration in early midlife can identify a small group of men at increased risk of prostate cancer metastasis several decades later. Careful surveillance is warranted in these men. Given existing data on the risk of death by PSA concentration at age 60, these results suggest that three lifetime PSA tests (mid to late 40s, early 50s, and 60) are probably sufficient for at least half of men.

Introduction

Screening for prostate cancer with the prostate specific antigen (PSA) test became widespread long before the availability of randomised evidence as to its value. There is now evidence that PSA screening is associated with reduced mortality from prostate cancer in men who would not otherwise be screened,1 2 although this comes at considerable harms in terms of the number of men who need to be screened, undergo biopsy, and be treated to prevent one man experiencing prostate cancer metastasis or dying.

That said, PSA screening is not a single intervention and men can be screened in different ways. There is surprisingly little evidence to support many aspects of contemporary screening guidelines. In particular, the age at which screening starts and the frequency of PSA testing is rarely justified in terms of empirical data. Recent evidence has suggested that a single PSA measurement can predict the long term risk of clinically relevant prostate cancer.3 4 5 6 This suggests that a baseline concentration could be used to determine whether a man might benefit from subsequent PSA tests and, if so, when these should be administered.

We used data from the Malmö Preventive Project cohort to develop an evidence based schema for prostate cancer testing. We retrospectively analysed PSA in previously unthawed, archived, anticoagulated blood plasma obtained at baseline from a large highly representative population based cohort of men who had not been screened for PSA and had been followed for 25-30 years. As such, the cohort provides a “natural experiment” for investigating the association between PSA and long term prostate cancer outcomes.

Using this cohort, we previously showed that PSA concentration at age 60 can predict the risk of death from prostate cancer by age 85 (AUC of 0.90). In particular, the 25 year risk of death from prostate cancer in men with PSA below the median (≤1 µg/L) is low (0.2%) and suggests that half of the men at age 60 could be exempt from further screening.7 We determined the risk of metastasis or death from prostate cancer within 25-30 years based on PSA measured close to the time when screening is normally recommended to begin. As there was little screening for prostate cancer in our cohort, these results can be used to determine which men are most likely to benefit from screening.

Methods

Study cohort

The Malmö Preventive Project study has been previously described.5 8 The cohort includes 21 277 men (74% of the eligible population) aged 27-52 who participated in the project between 1974 and 1984 and gave a blood sample at baseline. Subsets of men from the age groups were then invited to provide a second blood sample about six years later, and 4922 (72%) of those re-invited complied. Participants’ records were linked to the cancer registry at the National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden to identify men diagnosed with incident prostate cancer up to 31 December 2006. The registry has been shown to be highly accurate.9 10

Published estimates of rates of PSA screening in Malmö indicate that it was extremely rare before 1995. Between 1995 and 2000, the proportion of men aged 55-69 who received a PSA test increased steadily from <1% to 10%; this proportion remained constant until 2005, after which it fell.11 Data from the European randomised trial of screening for prostate cancer (ERSPC)1 2 indicates that screening starts to have an effect on mortality only after eight years or longer of follow-up; moreover, the effect is initially small. Our study database was closed at the end of 2006 and so screening rates up to 1998 are of interest. Given that only about 5% of men would have received PSA screening during this time period, it is unlikely that any informal or opportunistic screening in Malmö could have substantively affected our estimates.

Outcomes ascertainment

We identified 1369 documented clinical diagnoses of prostate cancer, 241 cases of metastasis, and 162 deaths from prostate cancer. Metastasis cases were identified in one of three ways. Firstly, we obtained metastasis data based on stage at diagnosis from the National Prostate Cancer Registry data, with medical charts reviewed for 108 of 114 cases. Secondly, we reviewed medical charts for 1142 of 1369 men with a diagnosis of prostate cancer. This identified an additional 86 men who subsequently developed metastasis. Lastly, two urologists (TB and DU or AG) reviewed cause of death charts from the causes of death registry at the National of Health and Welfare in Sweden and medical charts for 198 of 370 men who died after an earlier diagnosis of prostate cancer; 41 men who died from prostate cancer without previous clinical documentation of metastases were considered to have prostate cancer metastases at their date of death. Of the 162 deaths from prostate cancer, 117 (72%) were independently reviewed, whereas for 45 (28%) cause of death was obtained from the registry. The rate of independent review did not differ importantly by age group. Chart and registry cause of death had a concordance rate of 82%. All chart reviews were conducted independently and blind to PSA concentration at baseline.

Laboratory methods

Assays to measure PSA in previously unthawed archival EDTA anticoagulated blood plasma were as previously described.7 Concentrations of PSA in samples frozen for over 20 years after the blood was drawn have been shown to be comparable with those in contemporaneously measured serum.12

Statistical considerations

To examine our specific research questions, we focused our analyses on men close to age 40 (range 37.5-42.5; n=3979), mid to late 40s (range 45-49; n=10 357), and early to mid-50s (range 51-55). The two younger age groups were subsets of the full cohort, with men providing blood at age below 44 (n=9108) or at age 44-51 (n=12 169) at baseline, while men in their early to mid-50s comprised all those who provided a blood sample about six years after baseline (n=4063).

We used a nested case-control design. The methods were as previously described,7 with three controls selected at random from the group of participants from the Malmö cohort who were alive and event free at the follow-up time at which the index case event occurred. Separate matching was conducted for the endpoints of metastasis and death. Predictive accuracy was assessed with Harrell’s concordance index. Total PSA concentrations were measured in samples from all men aged 51-55, which is why we did not use a case-control approach for analyses of data from this age group. Appendix 1 provides a flow chart describing participants.

We estimated absolute risk and the cumulative proportion (Lorenz curve13) of metastases and death by centiles of the PSA distribution. We imputed PSA measurements for men without prostate cancer who were not selected as controls and for a small number of men with prostate cancer whose blood samples were not available (n=23) using predictive mean matching based on age and follow-up time, stratified by case control status. Table 1 summarises the number of men whose blood measurements were imputed for each age group. Confidence intervals were estimated with Rubin’s method.14 A validation study on our imputation method is described in appendix 2.

Table 1.

Concentrations of prostate specific antigen (PSA) in men with prostate cancer metastasis (cases), controls, and men not selected as controls in participants from Malmö cohort

| Age (years) at screening | Prostate cancer metastasis | Selected controls | Not selected as controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With measured PSA* | With imputed PSA† | |||

| 37.5-42.5 at baseline | ||||

| No of participants | 18 | 54 | 710 | 3197 |

| Median (IQR) total PSA (µg/L) | 0.63 (0.49-1.42) | 0.62 (0.48-0.97) | 0.63 (0.43-0.94) | 0.61 (0.41-0.89) |

| 45-49 at baseline | ||||

| No of participants | 198 | 514 | 3190 | 6455 |

| Median (IQR) total PSA (µg/L) | 1.11 (0.62-2.41) | 0.60 (0.41-0.94) | 0.68 (0.43-1.04) | 0.68 (0.44-1.07) |

| 51-55 at second screen | ||||

| No of participants | 93 | 3970 | 0 | 0 |

| Median (IQR) total PSA (µg/L) | 1.67 (0.97-5.29) | 0.84 (0.52-1.36) | NA‡ | NA‡ |

IQR=interquartile range.

*PSA concentrations measured as part of another study.

†PSA concentrations for men without prostate cancer not selected as controls imputed to calculate population based estimates of risk.

‡PSA measured in all men.

We used estimates of risk and cumulative proportion to examine a series of practical questions. Firstly, we evaluated whether there was any rationale for starting screening before age 45. We looked at cumulative incidence of metastases at 15 years. We chose this time point on the grounds that, taking into account lead time, metastases occurring more than 15 years later could probably be detected at a curable stage by a repeat screen within seven or eight years. Secondly, we evaluated whether a single test at age 45-49 or age 51-55 could exempt some men from further screening or, conversely, identify a small group of men at greatly increased risk. Thirdly, we determined the screening interval for men at low risk, again by looking at risk of metastases within 15 years. All analyses were conducted with Stata 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the cases and controls for the respective age groups. Total PSA concentrations are similar to population estimates from the United States.15 16

In the cohort as a whole, PSA concentration was significantly associated with evidence of prostate cancer metastasis documented up to 30 years later (P<0.005). Concentrations tended to become more predictive at older ages with a C index of 0.635, 0.719, and 0.749 for the 40 year old cohort, mid to late 40s, and early 50s cohort, respectively. Concentrations were also significantly associated with risk of death from prostate cancer, with C index of 0.670, 0.718, and 0.755, respectively, for the three age cohorts. In the men who returned for a second screening at age 51-55, first and second PSA concentrations were highly correlated (0.71).

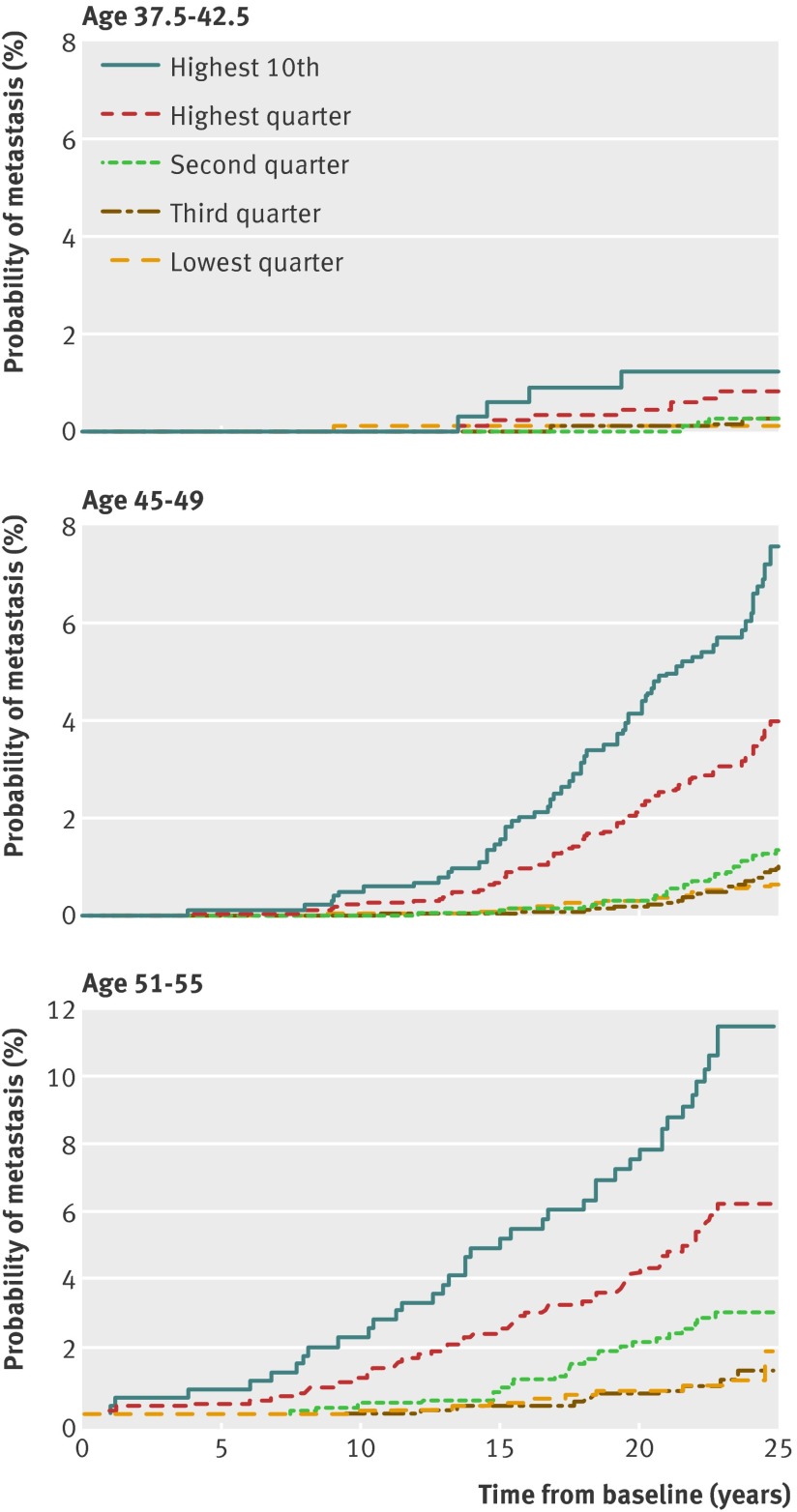

We examined whether PSA screening should start at age 40, mid to late 40s or early 50s. Even for men with PSA in the highest 10th (≥1.3 µg/L) at age 40, the risk of prostate cancer metastases by 15 years’ follow-up is low (0.6%) (fig 1 ). Although the 95% confidence interval was wide (0.1% to 2.4%) because of the limited number of events in this analysis, it would nonetheless seem likely that only a few tumours would become incurable between the ages of 40 and 45. Therefore it is difficult to justify initiating PSA testing at age 40 for men with no other relevant risk factor (such as mutations in BRCA2, BRCA1,17 or HOXB1318). In contrast, the risk of metastases within 15 years was close to threefold higher (1.6%) for men in the highest 10th at age 45-49, and close to tenfold higher (5.2%) at age 51-55, suggesting that not starting PSA based screening until age 51-55 would leave an important proportion of men at a considerably increased risk of later being diagnosed with an incurable cancer.

Fig 1 Cumulative incidence of evidence of metastasis or death from prostate cancer by centile of PSA concentration at various ages

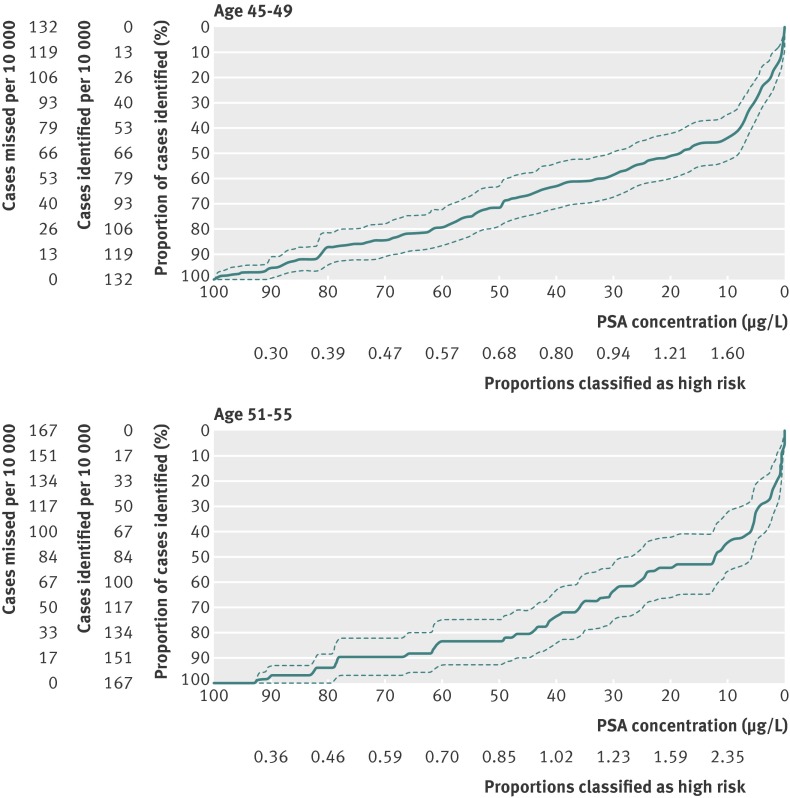

Our second objective was to determine whether men with PSA concentrations below the median in their mid to late 40s could be exempted from further screening. Although the absolute risk of metastasis within 25 years for men with PSA below median at age 45-49 was 0.85%, with a corresponding estimate for men aged 51-55 of 1.63% (fig 1 , table 2, and table 3), a substantial proportion (28%, 95% confidence interval 22% to 35%) of the men with evidence of prostate cancer metastases at long term follow-up (median 27 years) had PSA concentration below median (<0.68 µg/L) at age 45-49, while 18% (95% confidence interval 10% to 26%) had PSA below median (<0.85 µg/L) at age 51-55 (table 4). These estimates seem too high to conclude that any subsequent PSA based screening would not be necessary for men with PSA below median before age 55. Furthermore, the Lorenz curves in figure 2 clearly illustrate the difficulty to determine any particular PSA concentration at age 45-49 or 51-55 below which the proportion of men dying from prostate cancer by 30 years’ follow-up would be sufficiently low to conclude that subsequent PSA testing would not be necessary.

Table 2.

Cumulative incidence of evidence of metastasis from prostate cancer, stratified by different concentration of PSA measured at various ages

| PSA concentration | PSA concentration (µg/L) | % Risk (95% CI) of metastasis within: | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 years | 20 years | 25 years | ||

| Age 37.5-42.5 at baseline screen | ||||

| Highest 10th | ≥1.3 | 0.60 (0.09 to 2.39) | 1.22 (0.35 to 3.24) | 1.22 (0.35 to 3.24) |

| Highest quarter | ≥0.90 | 0.22 (0.04 to 0.90) | 0.46 (0.14 to 1.21) | 0.80 (0.33 to 1.70) |

| Second quarter | 0.61-0.90 | 0 (NA) | 0 (NA) | 0.25 (0.04 to 0.97) |

| Third quarter | 0.42-0.61 | 0 (NA) | 0.10 (0.01 to 0.73) | 0.27 (0.05 to 1.03) |

| Lowest quarter | ≤0.42 | 0.10 (0.01 to 0.69) | 0.10 (0.01 to 0.69) | 0.10 (0.01 to 0.69) |

| Age 45-49 at baseline screen | ||||

| Highest 10th | ≥1.60 | 1.57 (0.86 to 2.66) | 4.14 (2.83 to 5.81) | 7.61 (5.74 to 9.82) |

| Highest quarter | ≥1.10 | 0.73 (0.42 to 1.20) | 2.18 (1.58 to 2.93) | 4.02 (3.16 to 5.03) |

| Second quarter | 0.68-1.10 | 0.09 (0.02 to 0.34) | 0.29 (0.12 to 0.62) | 1.38 (0.92 to 2.01) |

| Third quarter | 0.44-0.68 | 0.05 (<0.01 to 0.31) | 0.19 (0.06 to 0.48) | 1.02 (0.65 to 1.55) |

| Lowest quarter | ≤0.44 | 0.12 (0.03 to 0.37) | 0.30 (0.13 to 0.64) | 0.65 (0.35 to 1.11) |

| Below median | ≤0.68 | 0.09 (0.03 to 0.23) | 0.25 (0.13 to 0.45) | 0.85 (0.60 to 1.19) |

| ≤66th centile | ≤0.90 | 0.08 (0.03 to 0.19) | 0.22 (0.12 to 0.38) | 0.91 (0.67 to 1.20) |

| ≤73rd centile | ≤1.00 | 0.09 (0.04 to 0.20) | 0.24 (0.14 to 0.39) | 1.00 (0.76 to 1.28) |

| Age 51-55 at second screen | ||||

| Highest 10th | ≥2.40 | 5.18 (3.37 to 7.91) | 7.51 (5.24 to 10.70) | 11.44 (8.44 to 15.40) |

| Highest quarter | ≥1.40 | 2.51 (1.69 to 3.72) | 4.17 (3.05 to 5.70) | 6.20 (4.74 to 8.09) |

| Second quarter | 0.85-1.40 | 0.77 (0.37 to 1.61) | 2.12 (1.34 to 3.35) | 3.01 (2.02 to 4.48) |

| Third quarter | 0.53-0.85 | 0.22 (0.05 to 0.87) | 0.58 (0.24 to 1.39) | 1.24 (0.63 to 2.44) |

| Lowest quarter | ≤0.53 | 0.32 (0.10 to 1.00) | 0.68 (0.31 to 1.51) | 1.86 (0.69 to 4.97) |

| Below median | ≤0.85 | 0.28 (0.11 to 0.66) | 0.64 (0.35 to 1.15) | 1.63 (0.82 to 3.22) |

| ≤53rd centile | ≤0.90 | 0.31 (0.14 to 0.69) | 0.72 (0.42 to 1.24) | 1.67 (0.87 to 3.19) |

| ≤59th centile | ≤1.00 | 0.37 (0.19 to 0.74) | 0.89 (0.56 to 1.41) | 1.81 (1.03 to 3.15) |

NA=not applicable.

Table 3.

Cumulative incidence of evidence of death from prostate cancer, stratified by different concentration of PSA measured at various ages

| PSA concentration | PSA concentration (µg/L) | % Risk (95% CI) of death from prostate cancer within: | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 years | 20 years | 25 years | ||

| Age 37.5-42.5 at baseline screen | ||||

| Highest 10th | ≥1.30 | 0.60 (0.09 to 2.39) | 0.90 (0.21 to 2.79) | 1.23 (0.35 to 3.26) |

| Highest quarter | ≥0.90 | 0.22 (0.04 to 0.90) | 0.34 (0.08 to 1.05) | 0.70 (0.26 to 1.61) |

| Second quarter | 0.61-0.90 | 0 (NA) | 0 (NA) | 0.16 (0.01 to 0.97) |

| Third quarter | 0.42-0.61 | 0 (NA) | 0.10 (0.01 to 0.73) | 0.10 (0.01 to 0.73) |

| Lowest quarter | ≤0.42 | 0.10 (0.01 to 0.69) | 0.10 (0.01 to 0.69) | 0.10 (0.01 to 0.69) |

| Age 45-49 at baseline screen | ||||

| Highest 10th | ≥1.60 | 0.74 (0.31 to 1.57) | 2.42 (1.48 to 3.75) | 5.14 (3.63 to 7.04) |

| Highest quarter | ≥1.10 | 0.31 (0.13 to 0.66) | 1.18 (0.75 to 1.77) | 2.67 (1.97 to 3.54) |

| Second quarter | 0.68-1.10 | <0.01 (<0.01 to 0.07) | 0.24 (0.09 to 0.56) | 0.72 (0.40 to 1.21) |

| Third quarter | 0.44-0.68 | 0 (NA) | 0.09 (0.02 to 0.34) | 0.54 (0.28 to 0.96) |

| Lowest quarter | ≤0.44 | 0.08 (0.01 to 0.30) | 0.24 (0.09 to 0.54) | 0.52 (0.26 to 0.96) |

| Below median | ≤0.68 | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.16) | 0.17 (0.08 to 0.34) | 0.55 (0.35 to 0.83) |

| ≤66th centile | ≤0.90 | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.12) | 0.14 (0.07 to 0.28) | 0.51 (0.34 to 0.74) |

| ≤73rd centile | ≤1.00 | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.11) | 0.17 (0.09 to 0.30) | 0.56 (0.39 to 0.79) |

| Age 51-55 at second screen | ||||

| Highest 10th | ≥2.40 | 3.38 (1.97 to 5.75) | 5.68 (3.74 to 8.59) | 9.03 (6.34 to 12.78) |

| Highest quarter | ≥1.40 | 1.80 (1.12 to 2.88) | 2.98 (2.05 to 4.33) | 5.07 (3.70 to 6.93) |

| Second quarter | 0.85-1.40 | 0.66 (0.30 to 1.47) | 1.67 (0.99 to 2.81) | 2.09 (1.30 to 3.35) |

| Third quarter | 0.53-0.85 | 0.11 (0.02 to 0.76) | 0.36 (0.12 to 1.12) | 0.62 (0.26 to 1.49) |

| Lowest quarter | ≤0.53 | 0.33 (0.11 to 1.02) | 0.57 (0.24 to 1.36) | 0.94 (0.44 to 2.02) |

| Below median | ≤0.85 | 0.22 (0.08 to 0.59) | 0.47 (0.24 to 0.94) | 0.80 (0.45 to 1.42) |

| ≤53rd centile | ≤0.90 | 0.26 (0.11 to 0.63) | 0.50 (0.26 to 0.96) | 0.81 (0.46 to 1.41) |

| ≤59th centile | ≤1.00 | 0.33 (0.16 to 0.69) | 0.64 (0.37 to 1.11) | 0.92 (0.57 to 1.50) |

NA=not applicable.

Table 4.

Proportion of deaths or metastases from prostate cancer captured by respective categories of increased concentrations of PSA at age 45-49 or 51-55

| PSA concentration (µg/L) | Proportion (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths | Metastases | ||

| Age 45-49 at baseline screen | |||

| Highest 10th | ≥1.6 | 44 (34 to 53) | 40 (33 to 48) |

| Highest quarter | ≥1.06 | 54 (45 to 63) | 51 (44 to 59) |

| Below median | <0.68 | 28 (20 to 37) | 28 (22 to 35) |

| Age 51-55 at second screen | |||

| Highest 10th | ≥2.4 | 44 (32 to 56) | 42 (32 to 52) |

| Highest quarter | ≥1.4 | 59 (47 to 71) | 56 (46 to 66) |

| Below median | <0.85 | 16 (7 to 25) | 18 (10 to 26) |

Fig 2 Lorenz curves for death from prostate cancer and 95% confidence intervals for PSA concentration at age 45-49 and 51-55

Given that these lower risk men cannot be exempted from subsequent screening, our next question concerned the appropriate screening interval. Figure 1, table 2, and table 3 show that the absolute risk of metastasis remains low within 15 years’ follow-up for men with lower PSA concentrations (that is, age median or lower). One possible cut point to determine more versus less frequent screening would be ≤1.0 µg/L: the risk of metastasis within 15 years is no higher than 0.4% (table 2) for any cohort, suggesting that a screening interval less than five years for these men is unnecessary. The proportions of men with PSA ≤1.0 µg/L were 73% and 59% at age 45-49 and 51-55, respectively; 56% had PSA ≤1.0 µg/L at both time points.

Figure 2 and table 4 examine our objective concerning risk concentration: 44% (95% confidence interval 34% to 53%) of deaths within 25-30 years were in men in the highest 10th of PSA concentrations (≥1.6 µg/L) at age 45-49, with a similar proportion in the highest 10th (≥2.4 µg/L) at age 51-55 . This suggests that close to half of all prostate cancers destined to lead to death would be detected early by careful surveillance of a small high risk subgroup.

As a sensitivity analysis, we repeated analyses using different age ranges, such as 42.5-47.5 (to assess the characteristics of PSA at age 45). No result was materially affected. We also examined the predictive accuracy of a model including both PSA and PSA velocity compared with PSA alone in men with a second sample. PSA velocity did not improve prediction of death from prostate cancer. Even after we excluded patients with outlying values, the C index increased by only 0.002.

Discussion

Overview of findings

PSA concentration can be used to predict of long term risk of metastasis or death from prostate cancer. It can identify a small group of men at greatly increased risk compared with a much larger group highly unlikely to develop prostate cancer morbidity if rescreening is delayed for seven or eight years. As PSA screening was extremely rare in this cohort, our findings can be used to design screening programmes by determining the age at which men should start to undergo screening and the interval between screenings. Men at low risk of death from prostate cancer without screening have little to gain from being screened but still risk overdiagnosis and overtreatment; men likely to die from prostate cancer without screening could avoid cancer specific mortality if they choose to be screened.

In an earlier paper, we showed that PSA concentration at age 60 had a strong association with the risk of death from prostate cancer by age 85 (AUC 0.90),7 with extremely low risk (≤0.2%) in men with PSA concentration below the median (≤1.0 µg/L). Taken together with our current data, this suggests a simple algorithm for prostate screening. All men with a reasonable life expectancy could be invited for PSA screening in their mid to late 40s. Men with a PSA concentration <1.0 µg/L would be advised to return for screening in their early 50s and then again at age 60, whereas men with PSA ≥1.0 µg/L would return for more frequent screening, with literature suggesting repeat tests every two or four years.19 The choice of 1.0 µg/L as a tentative threshold might vary according to preference. At age 60, men with PSA at median or lower—that is, ≤1.0 µg/L (or possibly below the highest quarter, ≤2.0 µg/L, depending on preference)—would then be exempted from further screening; men with a higher concentration would continue to undergo screening until around 70.1 Particular focus should be placed on men in the highest 10% of PSA concentrations at age 45-55, who will contribute close to half of all deaths from prostate cancer occurring before the age of 70-75. Some of these men will have concentrations above current thresholds for consideration of biopsy—such as 3 µg/L—and should be referred to a urologist. The remaining men could be told that, although they will probably not die from prostate cancer (with a mean risk of metastasis within 25 years close to 10%), they are at much higher risk than average and that it is especially important that they return for regular, frequent, and possibly more elaborate screening. It is also worth considering whether management of these men should become proactive, with reminder letters and attempts to follow-up non-compliers by telephone. Most importantly, the proposed PSA concentration of 1.0 µg/L to discriminate a low from a higher risk group is not suggested to serve as an indication for biopsy but rather be used to determine the frequency and intensity of subsequent monitoring.

Comparison with other studies

Our findings build on a considerable body of work suggesting that PSA concentration can predict the subsequent risk of prostate cancer in unscreened men.3 4 20 21 22 23 24 In one recent study, men aged 20-94 who gave a blood sample during the Copenhagen City Heart Study were followed for a median of 28 years. A PSA concentration of 4-10 µg/L was associated with a sevenfold risk of death from prostate cancer compared with concentrations ≤1 µg/L.25 Our study is distinguished by its size (>240 case of metastatic prostate cancer), length of follow-up (>25 years), inclusion of men at ages relevant to decisions about screening, and use of carefully ascertained metastasis or death from prostate cancer as an endpoint. This allows us to develop precise estimates of risk to inform screening policy.

Supportive evidence for our findings comes from van Leeuwen and colleagues, who analysed data from the European randomised trial of screening for prostate cancer (ERSPC). The investigators estimated the overall effect size of PSA screening if subsequent testing had been restricted to men with different PSA concentrations on the initial screening. They reported that among men with concentration <2 µg/L at age 55-69, corresponding to concentrations below the highest quarter among participants in ERSPC, a large number would need to be screened (around 25 000) and treated (around 700) to prevent one death from prostate cancer.26 An analysis of data from the ERSPC also supports our findings on the screening interval. Fewer than 1% of men with an initial PSA concentration <1 µg/L were found to have a concentration above the biopsy threshold of 3 µg/L at four year follow-up; the cancer detection rate by eight years was close to 1%. This led to a recommendation for an eight year screening interval for men with concentrations <1 µg/L.27

Limitations

Our cohort was almost exclusively white, and we do not know whether our risk estimates would apply to men of other races. One study on long term association between PSA concentrations and risk of prostate cancer in an unscreened US population reported that “there were no important or statistically significant differences in the performance of [PSA] by race,”21 suggesting applicability of our findings to other ethnicities.

Conclusions

PSA concentrations can indicate not only the current risk of cancer—and hence the need for prostate biopsy—but are also predictive of the future risk of prostate cancer metastasis and cancer specific death. Screening programmes can be designed to focus on men at highest risk, with three lifetime PSA tests between the ages of 45 and 60 sufficient for at least half of the male population. This is likely to reduce the risk of overdiagnosis while still enabling early cancer detection among those most likely to gain from early diagnosis. As such, a risk stratified approach to PSA screening will improve the ratio of its benefits and harms.

What is known on this topic

Prostate specific antigen screening is widely used for the early detection of prostate cancer but remains highly controversial.

Focusing on the men at highest risk of prostate cancer metastasis and death could improve the ratio between benefits and harms of screening.

What this study adds

It is difficult to justify initiating PSA screening at 40 for men with no other significant risk factor

Men with PSA in highest 10th at age 45-49 contribute nearly half of prostate cancer deaths over the next 25-30 years

At least half of all men can be identified as being at low risk, and probably need no more than three PSA tests lifetime (mid to late 40s, early 50s, and 60)

We thank Gun-Britt Eriksson, Kerstin Håkansson, and Mona Hassan Al-Battat for expert assistance with immunoassays. Abstracts containing a subset of the data contained in this manuscript were accepted and reported at the American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting in Chicago in June 2011 and at the American Urological Association meeting in Washington, DC, in May 2011.

Contributors: All authors contributed to and were solely responsible for the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and the decision to submit the article for publication. HL and AJV are guarantors.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (grant No R33 CA 127768-03, P50-CA92629); Swedish Cancer Society (11-0624); the Sidney Kimmel Center for Prostate and Urologic Cancers; David H Koch through the Prostate Cancer Foundation, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre based at Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust and University of Oxford, Fundación Federico SA, and MSKCC PCPR (Prevention Control and Population Research Program) Goldstein Grant. DU was supported by the David H Koch Young Investigator Award from the Prostate Cancer Foundation.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that HL holds patents for free PSA, intact PSA, and hK2 assays; HL, AJV, and PTS are named as co-inventors on a patent application for a statistical method to predict the result of prostate biopsy; HL has support from NIH, Swedish Cancer Society, and Arctic Partners; PS has support from OPKO Health; and AV has support from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Genomic Heath for the submitted work; HL has a patent and stock relationship with Arctic Partners; PS has a consultancy, patent, stock, and royalties relationship with OPKO; AV has a consultation and honorarium relationship with GSK, Genomic Heath, and OPKO.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the regional ethics board in Lund, Sweden with official record No 85/2004 for epidemiological studies.

Data sharing: Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author at. Consent was not obtained for data sharing but the presented data are anonymised and risk of identification is low.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;346:f2023

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author [posted as supplied]

Appendix 1: Flow chart of participants

Appendix 2: Validation of imputation approach and supplementary tables

References

- 1.Schroder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Tammela TL, Ciatto S, Nelen V, et al. Prostate-cancer mortality at 11 years of follow-up. N Engl J Med 2012;366:981-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hugosson J, Carlsson S, Aus G, Bergdahl S, Khatami A, Lodding P, et al. Mortality results from the Goteborg randomised population-based prostate-cancer screening trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:725-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stenman UH, Hakama M, Knekt P, Aromaa A, Teppo L, Leinonen J. Serum concentrations of prostate specific antigen and its complex with alpha 1-antichymotrypsin before diagnosis of prostate cancer. Lancet 1994;344:1594-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gann PH, Hennekens CH, Stampfer MJ. A prospective evaluation of plasma prostate-specific antigen for detection of prostatic cancer. JAMA 1995;273:289-94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lilja H, Ulmert D, Bjork T, Becker C, Serio AM, Nilsson JA, et al. Long-term prediction of prostate cancer up to 25 years before diagnosis of prostate cancer using prostate kallikreins measured at age 44 to 50 years. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:431-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ulmert D, Cronin AM, Bjork T, O’Brien MF, Scardino PT, Eastham JA, et al. Prostate-specific antigen at or before age 50 as a predictor of advanced prostate cancer diagnosed up to 25 years later: a case-control study. BMC Med 2008;6:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Bjork T, Manjer J, Nilsson PM, Dahlin A, et al. Prostate specific antigen concentration at age 60 and death or metastasis from prostate cancer: case-control study. BMJ 2010;341:c4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyssenko V, Jonsson A, Almgren P, Pulizzi N, Isomaa B, Tuomi T, et al. Clinical risk factors, DNA variants, and the development of type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2220-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barlow L, Westergren K, Holmberg L, Talback M. The completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register: a sample survey for year 1998. Acta Oncol 2009;48:27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandblom G, Dufmats M, Olsson M, Varenhorst E. Validity of a population-based cancer register in Sweden—an assessment of data reproducibility in the South-East Region Prostate Cancer Register. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2003;37:112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jonsson H, Holmstrom B, Duffy SW, Stattin P. Uptake of prostate-specific antigen testing for early prostate cancer detection in Sweden. Int J Cancer 2011;129:1881-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ulmert D, Becker C, Nilsson JA, Piironen T, Bjork T, Hugosson J, et al. Reproducibility and accuracy of measurements of free and total prostate-specific antigen in serum vs plasma after long-term storage at -20 degrees C. Clin Chem 2006;52:235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moskowitz CS, Seshan VE, Riedel ER, Begg CB. Estimating the empirical Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient in the presence of error with nested data. Stat Med 2008;27:3191-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley, 1987.

- 15.Anderson JR, Strickland D, Corbin D, Byrnes JA, Zweiback E. Age-specific reference ranges for serum prostate-specific antigen. Urology 1995;46:54-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalish LA, McKinlay JB. Serum prostate-specific antigen levels (PSA) in men without clinical evidence of prostate cancer: age-specific reference ranges for total PSA, free PSA, and percent free PSA. Urology 1999;54:1022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitra AV, Bancroft EK, Barbachano Y, Page EC, Foster CS, Jameson C, et al. Targeted prostate cancer screening in men with mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 detects aggressive prostate cancer: preliminary analysis of the results of the IMPACT study. BJU Int 2011;107:28-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ewing CM, Ray AM, Lange EM, Zuhlke KA, Robbins CM, Tembe WD, et al. Germline mutations in HOXB13 and prostate-cancer risk. N Engl J Med 2012;366:141-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Leeuwen PJ, Roobol MJ, Kranse R, Zappa M, Carlsson S, Bul M, et al. Towards an optimal interval for prostate cancer screening. Eur Urol 2012;61:171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carter HB, Pearson JD, Metter EJ, Brant LJ, Chan DW, Andres R, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of prostate-specific antigen levels in men with and without prostate disease. JAMA 1992;267:2215-20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whittemore AS, Lele C, Friedman GD, Stamey T, Vogelman JH, Orentreich N. Prostate-specific antigen as predictor of prostate cancer in black men and white men. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;87:354-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connolly D, Black A, Gavin A, Keane PF, Murray LJ. Baseline prostate-specific antigen level and risk of prostate cancer and prostate-specific mortality: diagnosis is dependent on the intensity of investigation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17:271-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuller LH, Thomas A, Grandits G, Neaton JD, Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research G. Elevated prostate-specific antigen levels up to 25 years prior to death from prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004;13:373-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bul M, van Leeuwen PJ, Zhu X, Schroder FH, Roobol MJ. Prostate cancer incidence and disease-specific survival of men with initial prostate-specific antigen less than 3.0 ng/ml who are participating in ERSPC Rotterdam. Eur Urol 2011:59:505. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Orsted DD, Nordestgaard BG, Jensen GB, Schnohr P, Bojesen SE. Prostate-specific antigen and long-term prediction of prostate cancer incidence and mortality in the general population. Eur Urol 2012;61:865-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Leeuwen PJ, Connolly D, Tammela TL, Auvinen A, Kranse R, Roobol MJ, et al. Balancing the harms and benefits of early detection of prostate cancer. Cancer 2010;116:4857-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roobol MJ, Roobol DW, Schroder FH. Is additional testing necessary in men with prostate-specific antigen levels of 1.0 ng/mL or less in a population-based screening setting? (ERSPC, section Rotterdam). Urology 2005;65:343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Flow chart of participants

Appendix 2: Validation of imputation approach and supplementary tables