Abstract

Background

The prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in females appears to be increasing. Recent studies have revealed that the percentage of women with COPD in Greece is approximately 12.5%.

Aims

To evaluate the burden of COPD among males and females in Greece through a nationwide cross-sectional survey and to explore sex differences regarding functional characteristics and exacerbation frequency.

Methods

Data collection was completed in a 6-month period. The present study followed a nationwide sampling approach of respiratory medicine physicians. The sampling approach included three steps: 1) estimation of expected incidence and prevalence of COPD cases in each prefecture of Greece and in total; 2) estimation of expected incidence of COPD cases per physician in each prefecture; and 3) creation of a frame of three different sampling zones. Following this sampling, data were provided by 199 respiratory physicians.

Results

The participating physicians provided data from 6,125 COPD patients. Female patients represented 28.7% of the study participants. Female COPD patients were, on average, 5 years younger than male COPD patients. Never smokers accounted for 9.4% within female patients, compared to 2.7% of males (P<0.001). Female patients were characterized by milder forms of the disease. Comorbidities were more prevalent in men, with the exception of gastroesophageal reflux (14.6% versus 17.1% for men and women, respectively, P=0.013). Female COPD patients had a higher expected number of outpatient visits per year (by 8.9%) than males (P<0.001), although hospital admissions did not differ significantly between sexes (P=0.116). Females had fewer absences from work due to COPD per year, by 19.0% (P<0.001), compared to males.

Conclusion

The differences observed between male and female COPD patients provide valuable information which could aid the prevention and management of COPD in Greece.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, exacerbations, comorbidities

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of morbidity and disability worldwide and one of the leading causes of mortality in the USA and Europe.1–3 COPD prevalence, together with COPD morbidity and mortality, varies not only across countries but also across different groups within the same country.4 The BOLD study (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease; a population-based prevalence survey of noninstitutionalized adults over 40 years of age) has shown that the prevalence of COPD in females was 8.5%, although there was significant variation among different areas.5 Previous studies in northern Greece showed that COPD prevalence ranged between 2.5% in women aged 21–80 years and increased with age,6 reaching 4.8% in female smokers aged above 35 years old.7 Furthermore, in these studies COPD prevalence ratio ranged from 2.42 to 3.28 between men and women.6,7 When health care use was examined, visits due to COPD in primary care settings reached 451.9/10,000 residents among men but only 269.4/10,000 residents (ie, 1.68 times lower) in women.8

In the US, the prevalence and mortality of COPD in females appears to be increasing,9 while in Greece a large number of patients remain undiagnosed.10 The lower percentage of women with COPD in Greece is probably related to the low smoking habit of Greek women in rural areas, as it has been recently reported that 96% of women above the age of 60 in northern Greece are nonsmokers.11

Recent studies have shown that disease manifestations differ between men and women;12,13 women tend to develop COPD at a younger age and have a shorter smoking history compared to men suffering from the disease of the same stage.13 Female patients with COPD seem to have fewer comorbidities, better arterial blood gases, lower BMI, a lower exercise capacity, a greater degree of dyspnea, and a lower health-related quality of life compared to male patients of the same COPD stage.12 These differences in COPD manifestations in women could possibly be the result of differences in tobacco susceptibility caused by a genetic susceptibility.14 According to the aforementioned observations, female COPD patients might require earlier diagnosis, closer disease monitoring, and more intensive therapeutic interventions compared to male COPD patients. The understanding of sex differences in COPD in our country might be helpful for the better design of a diagnostic and therapeutic strategy.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the burden of COPD among females in Greece in a large sample of COPD patients through a nationwide cross-sectional survey of respiratory medicine physicians and to explore sex differences regarding functional characteristics, smoking habit, and exacerbation frequency.

Methods

Study design

In order to estimate the nationwide rate of newly diagnosed cases, it was essential to take into account that COPD diagnosis and treatment could be performed either in hospitals or in the offices of private practitioners (mainly respiratory medicine physicians). The present study followed a nationwide sampling approach of respiratory medicine physicians. First, we estimated the expected incidence (new) and prevalence of COPD cases in Greece, in each prefecture (52 administrative areas covering the whole country) and in total. We used the range of various comparative and area-specific estimations of COPD incidence (and prevalence) ratios stratified per age group and sex published in the international literature,15,16 plus data on population age and sex strata in every prefecture from the Hellenic Statistical Authority.17 Next, in order to estimate the expected incidence of COPD cases per physician in each prefecture, we used data on the number of Greek pulmonologists per prefecture provided by the Hellenic Thoracic Society.18 Based on these ratios (ie, the expected COPD cases per physician in each prefecture) we created a frame of three different sampling zones by assigning in each zone prefectures with proximate ratios. These zones included the “tertiary hospital zone”, areas with very large hospitals, very high density of respiratory medicine physicians, and low ratios of expected COPD cases per physician; the “intermediate zone”, areas with large respiratory medicine departments and many private practitioners; and a third zone which included all remaining prefectures – areas with mostly aging rural populations and few respiratory medicine physicians.

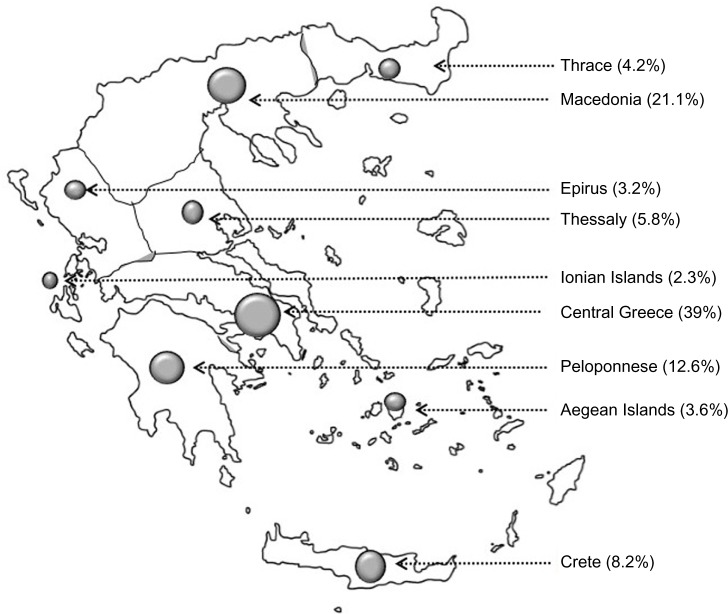

To cope with the (unknown) variation arising from possible differences among hospital respiratory medicine departments (ie, size, organizational factors, and other differences), we decided to include as many departments as feasible. Respiratory medicine physicians from 45 respiratory medicine departments throughout Greece participated. Both a convenience and judgment sampling (quota sampling) was employed. The respiratory medicine departments of the participating hospitals are shown in Table 1, and the areas of the country from which physicians have collected data are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Hospitals whose respiratory medicine departments have participated in the study

| Region | Location | Number of hospitals that participated in the study |

|---|---|---|

| Thessaly | Central Greece | 2 |

| Athens | Central Greece (Capital) | 7 |

| Chios | Aegean Sea (Island) | 1 |

| Crete | South Frontier of Greece (Island) | 4 |

| Ionian Region | Ionian Sea | 2 |

| Euboea | Central Greece | 1 |

| Lamia | Central Greece | 1 |

| Ioannina | West Greece | 2 |

| Peloponnese | Southern Greece | 2 |

| Thessaloniki | Northern Greece | 3 |

| Macedonia | Northern Greece | 3 |

| Thrace | Eastern Greece | 2 |

Figure 1.

The dots on this map of Greece signify the areas from where data have been collected; the size of each dot represents the number of patients included.

Respiratory care in the health system in Greece is organized in three levels: 1) general practitioners and private practice doctors offering mainly primary care services; 2) general hospitals offering secondary care, such as treatment in the emergency department and inpatient care; and 3) tertiary hospitals, usually university hospitals, which provide more specialized care, such as intermediate care units and intensive care units. For the needs of the present study, respiratory medicine physicians from all levels were recruited. All physicians were sampled at one time point. Study participants were COPD patients from all over the country who visited chest physicians either routinely or because of symptom deterioration.

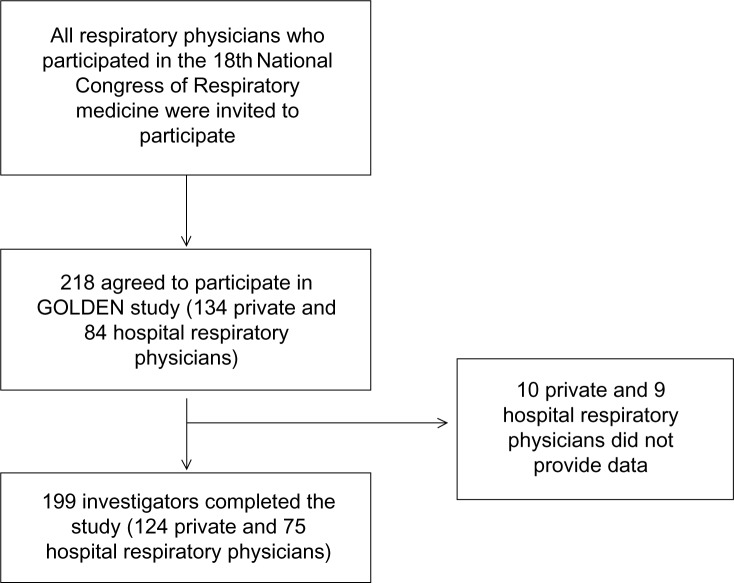

All data collection was performed over a 6-month period (October to March 2011). In total, 218 respiratory medicine physicians expressed interest in participating (134 private practitioners and 84 hospital doctors). At the end of the study, data were provided from 199 respiratory medicine physicians (124 private practitioners and 75 hospital doctors; response rate 92.5% and 89.3%, respectively) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow chart of the data collection.

Notes: In total, 218 respiratory medicine physicians agreed to collect and provide data (134 private respiratory medicine practitioners and 84 hospital doctors). At the end of the study, data were provided from 199 respiratory medicine physicians (124 private practitioners and 75 hospital doctors; response rate 92.5% and 89.3%, respectively).

Abbreviation: GOLDEN study, Greek Obstructive Lung Disease Epidemiology and health ecoNomics study.

During the 6-month study period, each respiratory medicine physician was asked to register all consecutive COPD patients visiting their clinic/office. Inclusion criteria included age greater than 40 years, a diagnosis of COPD established according to the GOLD (Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) criteria,4 residence in the prefecture of their practice, ability of the patient to provide data about their disease history, and consent of the patient to participate in the study. Patients who refused to participate, who had participated in a similar study during the last month, or had a history of asthma were excluded.

Each physician completed a questionnaire which included the patients’ demographics (ie, age, sex, occupation, place of residence, body mass index [BMI]), smoking status, time since diagnosis of COPD, current medication use (type, dose, and frequency), comorbidities, frequency of exacerbations, and hospitalizations for a COPD exacerbation and/or intensive care unit (ICU) admissions. The term “newly diagnosed COPD” was used for cases that were first diagnosed during the study period (ie, patients who were referred for the first time during the study period to a physician participating in the study and in whom the diagnosis was established with spirometry). Type I and Type II respiratory failure (ie, the presence of hypoxia, or hypoxia and hypercapnia, respectively) was also recorded. Sick leave days due to COPD and early retirement due to the disease were also recorded. Ex-smokers were defined as smokers who had quit smoking for at least 12 months. Smoking history was measured by pack-years, defined as the number of cigarettes smoked per day divided by 20 and multiplied by the number of years of smoking. According to their smoking history, subjects were classified into three categories: never-smokers, ex-smokers, and current smokers. Compliance with therapy was assessed by physicians according to the monthly prescription of medication and the patients’ and/or relatives’ reporting on the regular use of the prescribed medication.

Pre- and postbronchodilation spirometry measurements were performed in all study subjects and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and FEV1/FVC ratio were recorded. Postbronchodilator values (ie, 30 minutes after the administration of 400 μg salbutamol with a spacer) were used for the evaluation of COPD severity, according to GOLD guidelines (Stage I: mild COPD, FEV1 >80.0% predicted; Stage II: moderate COPD, 50.0%≤ FEV1 <80.0% predicted; Stage III: severe COPD, 30.0%≤ FEV1 <50.0%; Stage IV: very severe COPD, FEV1 <30.0%, or FEV1 <50.0% predicted with respiratory failure).4

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of all hospitals where the study was performed, as well as the National Organization for Medicines. All subjects provided written informed consent.

Statistical methods and analysis

For the description of the qualitative variables, absolute (number of observations) and relative frequencies (percentages) were used. The description of the quantitative variables was based on the calculation of the median and the interquartile range (IQR). The association of the qualitative variables with sex was clarified using Pearson’s χ2 test. The statistical evaluation of the differentiation of the quantitative variables according to sex was based on the application of the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test.

For the investigation of the effect of sex (adjusted for the other factors) on hospitalization in ICU, and on retirement due to COPD, logistic regression was applied. For the analysis of the number of exacerbations in the preceding year, hospitalizations (per year), days of hospitalization per exacerbation, days of hospitalization in ICU, days of absence from work (per year) and number of outpatient visits (per year), zero-inflated Poisson regressions were applied. The use of zero-inflated Poisson regression instead of the familiar Poisson regression is justified by the high number of zero values in our data.19 This choice was documented using a Vuong statistical test.19

Results

Study participants

In total, 199 respiratory medicine physicians provided data from 6,125 COPD patients. There were no differences regarding the location of practice, training, or patient population between physicians who provided data and those who did not. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study subjects are shown in Table 2. Female patients represented 28.7% of the study participants and were on average 5 years younger than male COPD patients (median 64 versus [vs] 69 for female and male COPD patients, respectively, P<0.001). Female COPD patients seemed to have lower BMI: 27.3 kg/m2 vs 27.7 kg/m2 for female and male COPD patients, respectively (P=0.036), although this difference might not have clinical significance.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants

| Sex

|

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male N=4,367 |

Female N=1,758 |

||

| Age, years | 69 (60.5–73) | 64 (56–73) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.7 (25.1–30.5) | 27.3 (24.4–31.2) | <0.036 |

| Smoking status | N=4,305 | N=1,694 | |

| Current smokers | 1,982 (46.0) | 887 (52.4) | <0.001 |

| Ex-smokers | 2,061 (47.9) | 458 (27.3) | <0.001 |

| Never smokers | 262 (6.1) | 349 (20.6) | <0.001 |

| Pack-years | 52 (36–75) | 35 (22–50) | <0.001 |

| GOLD COPD stage | N=4,360 | N=1,754 | <0.001 |

| I | 749 (17.2) | 432 (24.6) | |

| II | 1,521 (34.9) | 646 (36.8) | |

| III | 1,125 (25.8) | 442 (25.2) | |

| IV | 965 (22.1) | 234 (13.3) | |

| Newly diagnosed cases | 720 (17.1) | 344 (20.2) | 0.005 |

| Therapy compliance (how often someone forgets to take his/her medication) | 0.854 | ||

| Never/almost never | 2,320 (54.8) | 922 (53.9) | |

| <3 times a month | 904 (21.4) | 372 (21.7) | |

| 1 time a week | 477 (11.3) | 189 (11.0) | |

| >1 time a week or almost every day | 532 (12.6) | 228 (13.3) | |

| Respiratory failure – Type I | 1,023 (23.6) | 399 (22.9) | 0.544 |

| Respiratory failure – Type II | 495 (11.5) | 129 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| Use of nebulizer | 1,003 (23.0) | 313 (17.9) | <0.001 |

| Noninvasive mechanical ventilation | 151 (3.5) | 50 (2.9) | 0.222 |

| Number of exacerbations in the preceding year | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.826 |

| Number of hospitalizations in the preceding year | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.116 |

| Hospitalization in ICU | 186 (4.3) | 49 (2.8) | 0.007 |

Note: Data are presented as median (interquartile ranges) for numerical variables or as number (%) for categorical variables.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GOLD, Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; ICU, intensive care unit.

Only 4.6% of the COPD patients who participated in the study were never smokers. Never smokers accounted for 9.4% among female patients, compared to 2.7% among male patients (P<0.001). Male patients had more pack-years compared to female patients (median [IQR]: 52 [36–75] vs 35 [22–50]) for male and female patients, respectively, P<0.001). Finally, among women, current smokers were younger compared to ex-smokers and never smokers (62.3±0.2 years vs 69.0±0.4 years, P<0.001), and never smokers were older compared to current smokers and ex-smokers (69.5±0.5 years vs 62.9±0.2 years, P<0.001).

COPD diagnosis and severity

Newly diagnosed COPD cases were more prominent in females than in males (20.2% vs 17.1%, P=0.005). Furthermore, female patients were found to have a more recent diagnosis of COPD compared to male patients (median [IQR]: 8 [4–12] years vs 10 [5–15] years) for females and males, respectively (P<0.001).

COPD severity (defined by the GOLD COPD stage)4 was significantly related to sex; 24.6% of females were diagnosed as COPD GOLD Stage I compared to 17.2% of males, while 13.3% of females were diagnosed as COPD GOLD Stage IV compared to 22.1% of males. Severe and very severe disease (GOLD Stages III and IV) was more prominent in male patients (47.9% vs 38.5; P<0.001 for male and female patients, respectively).

COPD exacerbations and hospital admissions

A median of two exacerbations during the preceding year was reported in our study, with no difference between males and females (P=0.826). Hospital admissions also did not differ significantly between sexes (P=0.116).

The odds of hospitalization in the ICU tended to be lower in female COPD patients by 35.6% compared to males (odds ratio [OR] 0.644; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.468–0.887, P=0.007). However, multivariate analysis after adjustment for age, occupation, BMI, duration of COPD, COPD severity, smoking status, compliance to therapy, and comorbid conditions did not reveal any difference between sexes (OR 0.614; 95% CI: 0.335–1.0.69, P=0.082).

Comorbidities

The majority of COPD patients who participated in the study reported at least one comorbid condition (Table 3). The most common comorbidities were arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, gastroesophageal reflux, bronchiectasis, and sleep apnea syndrome. Comorbid conditions were more prevalent in men, with the exception of gastroesophageal reflux, which was more prevalent in women (14.6% vs 17.1% for men and women, respectively, P=0.013). It is worth mentioning that 16.4% of men and 13.6% of women reported at least four comorbidities, including COPD.

Table 3.

Comorbid diseases in the study participants

| (A) Number of comorbid diseases, COPD not included | Male N=4,367 N (%) |

Female N=1,758 N (%) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 742 (17.4) | 351 (20.3) | P=0.015 |

| 1 | 1,114 (26.1) | 453 (26.2) | |

| 2 | 1,012 (23.7) | 418 (24.1) | |

| 3 | 708 (16.6) | 274 (15.8) | |

| 4+ | 699 (16.4) | 235 (13.6) | |

|

| |||

| (B) Most common comorbid diseases |

Male N=4,367 N (%) |

Female N=1,758 N (%) |

P-value |

|

| |||

| Arterial hypertension | 2,514 (57.8) | 865 (49.3) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 917 (21.1) | 336 (19.2) | 0.094 |

| Congestive heart failure | 933 (21.5) | 252 (14.4) | <0.001 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 634 (14.6) | 300 (17.1) | 0.013 |

| Bronchiectasis | 595 (13.7) | 265 (15.1) | 0.146 |

| Cor pulmonale | 487 (11.2) | 123 (7.0) | <0.001 |

| Latent tuberculosis | 419 (9.6) | 119 (6.8) | <0.001 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome | 329 (7.6) | 99 (5.7) | 0.008 |

Note: Statistically significant differences between male and female patients are shown in bold.

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Heath care utilization

Outpatient care

Outpatient care during the preceding year included various tests such as chest X-ray, spirometry, computed tomography of the chest, measurement of arterial blood gases, and bronchoscopy (Table 4). No particular sex difference was observed in diagnostic tests performed on outpatient COPD patients during the preceding year, with the exception of arterial blood gases analysis, which was performed more often in male patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

Most common diagnostic tests performed to outpatient study participants during the preceding year

| Most common diagnostic tests | Male N=4,367 N (%) |

Female N=1,758 N (%) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chest X-ray | 3,000 (72.5) | 1,160 (70.4) | 0.114 |

| Spirometry | 2,999 (72.6) | 1,163 (70.7) | 0.151 |

| Blood gases | 1,573 (38.3) | 557 (34.0) | 0.002 |

| Computed tomography | 602 (14.7) | 232 (14.2) | 0.595 |

| Bronchoscopy | 154 (3.8) | 55 (3.4) | 0.449 |

| Other | 844 (20.7) | 350 (21.5) | 0.504 |

In univariate analysis (Table 5), patients aged 61–75 years and 76 years and older seemed to have a higher expected number of outpatient visits per year, by 11.3% and 13.7%, respectively, compared to younger patients. However, this was not confirmed in the multivariate analysis. Female COPD patients had a higher expected number of outpatient visits per year by 8.9% compared to males (univariate analysis, P<0.001), with a slightly lower but still significant difference in the multivariate analysis. Other significant predictors of increased outpatient health care utilization were severe and very severe disease (GOLD Stages III and IV), multiple comorbid diseases, previous established COPD diagnosis, and good compliance to COPD pharmacological treatment (Table 5). In contrast, newly diagnosed cases, and patients with poor compliance to COPD treatment provided a decreased expected number of outpatient visits (Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of the number of outpatient visits per year (results from a zero-inflated Poisson model)

| Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

|||||

| IRR | 95% CI | P-value | IRR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| ≤60* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 61–75 | 1.113 | (1.069–1.159) | <0.001 | 0.922 | (0.874–0.974) | 0.003 |

| 76+ | 1.137 | (1.085–1.192) | <0.001 | 0.832 | (0.779–0.889) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 1.089 | (1.051–1.129) | <0.001 | 1.057 | (1.000–1.116) | 0.049 |

| Body mass index | ||||||

| Normal* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Overweight | 0.942 | (0.904–0.981) | 0.004 | 0.898 | (0.856–0.943) | <0.001 |

| Obese | 1.109 | (1.063–1.156) | <0.001 | 1.044 | (0.992–1.098) | 0.1 |

| Duration of COPD (years) | ||||||

| ≤5* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 6–10 | 1.154 | (1.101–1.209) | <0.001 | 1.129 | (1.070–1.191) | <0.001 |

| 11+ | 1.472 | (1.408–1.539) | <0.001 | 1.36 | (1.289–1.435) | <0.001 |

| Newly diagnosed case | ||||||

| No* | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 0.683 | (0.648–0.720) | <0.001 | 1.023 | (0.942–1.111) | 0.588 |

| Severity of COPD (GOLD scale) | ||||||

| I* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| II | 0.942 | (0.892–0.995) | 0.031 | 0.838 | (0.782–0.898) | <0.001 |

| III | 1.287 | (1.219–1.359) | <0.001 | 1.021 | (0.952–1.095) | 0.565 |

| IV | 1.525 | (1.445–1.609) | <0.001 | 1.193 | (1.110–1.281) | <0.001 |

| Intake of medication | ||||||

| No* | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 1.198 | (1.132–1.267) | <0.001 | 0.978 | (0.907–1.055) | 0.570 |

| Medicine omission | ||||||

| No* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.887 | (0.858–0.916) | <0.001 | 0.849 | (0.815–0.884) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never smoker* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Ex-smokers | 0.88 | (0.833–0.930) | <0.001 | 0.861 | (0.803–0.924) | <0.001 |

| Light smokers (<20 pack-years) | 0.933 | (0.860–1.012) | 0.095 | 1.034 | (0.932–1.147) | 0.527 |

| Heavy smokers (>20 pack-years) | 0.826 | (0.780–0.874) | <0.001 | 0.904 | (0.841–0.973) | 0.007 |

| Comorbidity (number of diseases) | ||||||

| 0* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1 | 1.26 | (1.178–1.348) | <0.001 | 1.202 | (1.110–1.300) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 1.464 | (1.371–1.563) | <0.001 | 1.295 | (1.196–1.401) | <0.001 |

| 3 | 1.79 | (1.676–1.912) | <0.001 | 1.492 | (1.378–1.615) | <0.001 |

| 4+ | 1.919 | (1.799–2.048) | <0.001 | 1.455 | (1.341–1.578) | <0.001 |

Note:

Reference category.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GOLD, Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Absence from work due to COPD

Results from the comparison between sexes on the number of sick-leave days, excluding patients older than 65 years (ie, mostly pensioners) and homemakers revealed that females had a lower number of days of absence from work due to COPD per year by 19.0% (P<0.001) compared to males, after adjusting for the covariates of the model (Table 6). During the preceding year, the majority of COPD patients (83.7%) did not take sick leave due to COPD. Among those with sickness absence, females took mainly short sick leaves (up to 6 days), 39% of females compared to 30.1% for males; while 26.2% of male patients reported more than 20 days of sick leave during the preceding year compared to 15.6% of females.

Table 6.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of the number of days of absence from work due to COPD per year for patients aged <65 years whose occupation is not household and are not retired or unemployed (results from a zero-inflated Poisson model)

| Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | 95% CI | P-value | IRR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 0.718 | (0.676–0.763) | <0.001 | 0.810 | (0.753–0.871) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||||

| Normal* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Overweight | 1.007 | (0.943–1.075) | 0.841 | 0.839 | (0.776–0.906) | <0.001 |

| Obese | 1.471 | (1.376–1.573) | <0.001 | 1.032 | (0.951–1.120) | 0.447 |

| Duration of COPD (years) | ||||||

| <5* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 6–10 | 1.278 | (1.199–1.363) | <0.001 | 1.065 | (0.991–1.144) | 0.089 |

| 11+ | 1.602 | (1.499–1.712) | <0.001 | 0.980 | (0.902–1.065) | 0.641 |

| Newly diagnosed case | ||||||

| No* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.759 | (0.710–0.812) | <0.001 | 0.881 | (0.790–0.983) | 0.024 |

| Severity of COPD (GOLD scale) | ||||||

| I* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| II | 1.206 | (1.113–1.308) | <0.001 | 1.118 | (1.010–1.238) | 0.032 |

| III | 1.855 | (1.715–2.007) | <0.001 | 1.597 | (1.435–1.777) | <0.001 |

| IV | 3.090 | (2.840–3.361) | <0.001 | 1.905 | (1.696–2.139) | <0.001 |

| Intake of medication | ||||||

| No* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.817 | (0.763–0.875) | <0.001 | 0.559 | (0.514–0.609) | <0.001 |

| Medicine omission | ||||||

| No* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.055 | (1.002–1.111) | 0.043 | 1.003 | (0.939–1.071) | 0.927 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never smoker* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Ex-smokers | 1.193 | (1.048–1.358) | 0.007 | 0.846 | (0.712–1.004) | 0.056 |

| Light smokers (<20 pack-years) | 0.959 | (0.829–1.110) | 0.576 | 0.800 | (0.661–0.967) | 0.021 |

| Heavy smokers (>20 pack-years) | 1.144 | (1.010–1.296) | 0.034 | 0.967 | (0.817–1.144) | 0.694 |

| Comorbidity (number of diseases) | ||||||

| 0* | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1 | 1.046 | (0.958–1.142) | 0.317 | 0.981 | (0.880–1.094) | 0.736 |

| 2 | 1.259 | (1.154–1.373) | <0.001 | 1.039 | (0.929–1.162) | 0.500 |

| 3 | 1.666 | (1.514–1.833) | <0.001 | 1.494 | (1.321–1.689) | <0.001 |

| 4+ | 3.071 | (2.832–3.330) | <0.001 | 2.355 | (2.102–2.639) | <0.001 |

Note:

Reference category.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GOLD, Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Results from the univariate analysis of days of absence from work due to COPD per year for patients aged <65 years are listed in Table 6. Females had a lower number of sick leave days per year by 28.2% (P<0.001) compared to males. Obese patients and patients who omitted medication had an increased number of sick leave days by 47.1% (P<0.001), and 5.5% (P=0.043), respectively. Patients with higher comorbidity, more severe COPD (GOLD stage), and longer disease duration had a two- to threefold increase in the number of sick leave days (Table 6).

Furthermore, patients with COPD GOLD Stage II, III, and IV had a higher number of days of absence from work due to COPD per year by 11.8% (P=0.032), 59.7% (P<0.001), and 90.5% (P<0.001), respectively, compared to patients with mild COPD (GOLD 1), after adjusting for the covariates of the model. Patients with good compliance to therapy (as expressed by the intake of medication) as well as patients with newly diagnosed COPD had fewer expected days of absence from work due to COPD per year by 44.1% (P<0.001) and 11.9% (P=0.024), respectively, after adjusting for the covariates of the model. Patients with three and four or more comorbidities had increased expected number of days of absence from work (incidence rate ratio [IRR] [95% CI], 1.494 [1.321–1.689], P<0.001 and 2.355 [2.102–2.639], P<0.001, respectively) compared to patients with no comorbidities, after adjusting for the covariates of the model (Table 6).

Discussion

In the Greek Obstructive Lung Disease Epidemiology and health ecoNomics (GOLDEN) study GOLDEN cross-sectional study, more than 6,000 COPD patients provided a plethora of useful data on various aspects of COPD in Greece. In our study population, female patients have a shorter smoking history and less severe disease (according to the GOLD classification) compared to male COPD patients. Furthermore, although female patients with COPD in Greece report fewer comorbid conditions and they are less likely to be admitted to the hospital compared to males, they have reported significantly more outpatient visits. Finally, female COPD patients in Greece have fewer sick leave days due to COPD compared to male COPD patients.

The well-known impact of smoking as the main cause of COPD4 is also shown in our study, since only 4.6% of our study participants were never smokers. Indoor pollution is also a common cause for COPD development; causes such as passive smoking as well as the use of biomass (wood, crop residues, twigs, shrubs, dried dung, and charcoal) and coal, collectively known as solid fuels, which are used to meet basic domestic energy demands for cooking, lighting, and heating, have been associated with COPD in nonsmokers.20 Among COPD patients, never smokers were significantly more frequently women than men. This is in agreement with the Greek culture, since the great majority of older females are more likely to be never smokers. Interestingly, a high number of women in Greece are homemakers, responsible for the cooking and heating, being thus exposed to biomass fuels. These facts in combination with their possible exposure to passive smoking might explain the fact that they are the majority of the never smokers among Greek COPD patients.

Our study results are in agreement with previous observations reporting that female COPD patients are younger and have a lower BMI compared to male patients of the same COPD stage.13 Interestingly, in our population, female patients were reported to have more outpatient visits, although they did not have more hospital admissions or more severe disease. This is probably related to a social–sex characteristic (at least in Greece) which makes it more likely for females to seek medical care earlier than males21 and therefore be diagnosed in a less severe COPD stage.

Although previous studies have shown that comorbid conditions were highly prevalent in women,12 in our study, comorbid conditions such as hypertension and heart failure were more prevalent in men. This fact could be possibly explained by the age difference between male and female patients, but also by the fact that male COPD patients had more severe airflow limitation, also found to be related to increased prevalence of comorbidities.22 Interestingly, the only comorbid condition which was more prevalent in female patients from our study group was gastroesophageal reflux. Previous studies have shown a dose-dependent association between body mass and reflux esophagitis in women as opposed to no association among men, which is probably related to estrogen activity in obese females.23 The fact that a great percentage of female patients were at least overweight (median BMI 27.3 kg/m2, IQR 24.4–31.2) in our study probably contributes to the increased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux.

Although female COPD patients reported more outpatient visits, multivariate analysis after adjustment for age, occupation, BMI, duration of COPD, COPD severity, smoking status, and comorbid conditions did not reveal any difference in hospitalizations and ICU admissions between sexes. Previous studies have shown that disease severity and comorbidities are related to more frequent exacerbations.24,25 However, in our study, although males had more comorbidities, they did not appear to have more hospital and ICU admissions. A study in Norway has shown that the use of outpatient services was also related to several cultural and socioeconomic characteristics and was more frequent in women over 60 years of age.26

Finally, we have shown that although female COPD patients had more outpatient visits, they experienced fewer absences from work due to COPD compared to male patients. This may be due to greater sickness presenteeism among females or employment in less physically demanding jobs compared to men.

Our study has several limitations. First, even though the quota is a nonprobability (nonrandom) sampling, it was judged as not introducing any significant bias in the study. However, it is possible that this sampling method might limit the generalizability of the results. Second, there could be a possible selection bias due to the time period and seasonal variations, especially regarding COPD exacerbations. This is due to the fact that COPD exacerbations (which are related to symptoms deterioration) are more frequent during the winter season,27 which may lead more COPD patients to seek medical assessment. Additionally, variation could have been introduced by the fact that many patients with less severe disease might not look for medical advice or might be treated by general practitioners and internists rather than by respiratory medicine physicians. To a limited extent, recall bias for the self-reported variables is possible, although the involvement of expert physicians ensured the validity of the data collected. Finally, comorbidities were recorded according to the patients’ medical history and his/her personal medical files. According to the Greek medical system, medical files contain information on diagnostic examinations and their results as well as all information on the prescribed medication for each condition diagnosed. The respiratory medicine physicians who participated in the GOLDEN study did not perform additional tests to confirm the diagnosis of a comorbid condition for the study purposes (unless necessary for the routine care of the patient); it is thus possible that in some patients, this led to an under-diagnosis of comorbid conditions.

In conclusion, the GOLDEN study has provided a wealth of information that can enhance the understanding of the possible differences between male and female Greek COPD patients. Although Greek female COPD patients present with less severe disease and have fewer comorbidities compared to Greek male patients, they remain an important part of the COPD population regarding the use of health care services in both outpatient and inpatient care.

The differences observed reveal certain cultural characteristics related to sex and disease prevalence, such as smoking history and earlier COPD diagnosis for females. It is evident that both males and females have to be informed and educated from a younger age on the deleterious effects of smoking and encouraged to attend smoking cessation programs. The fact that in Greece COPD is prevalent even in never smoker females indicates that the physicians should be sensitized for COPD diagnosis in females, even when there is no smoking history. The frequent outpatient visits and health care facilities utilization increase the cost of COPD care. Hence, COPD patients should be educated on the early identification and better management of their symptoms as well as on the identification, reporting, and management of COPD exacerbations. This could potentially reduce costs and unnecessary utilization of health care services. The differences observed between male and female COPD patients provide important information which could set the foundations for the better prevention and management of the disease in Greece.

GOLDEN investigators list

Theodora Kerenidi, Eleni Karetsi, Nikolaos Poulakis, Chrysovalantis Papageorgiou, Aggeliki Rapti, Georgios Tsoukalas, Vasileios Tzilas, Georgatou Niki, Konstantinos Marosis, Haris Mpitsakou, Penny Moraiti, Mihail Toumpis, Asimina Gaga, Theoplasti Grigoratou, Evangelia Hondrou, Maria Kokkala, Dimitrios Veldekis, Fotios Vlastos, Georgios Heilas, Aspasia Chrisofaki, Stylianos Mihailidis, Vasiliki Filaditaki, Vlassios Polychronopoulos, Anastasia Amfilohiou, Georgios Tatsis, Paraskevi Katsaounou, Spyridon Papiris, Stylianos Loukidis, Eleni Gaki, Konstantinos Katis, Aikaterini Haniotou, Efstathia Evangellopoulou, Theodosios Panagiotakopoulos, Panagiotis Stratopoulos, Theoharis Dimou, Dimitris Georgopoulos, Aikaterini Varela, Spyridon Ganiaris, Nikolaos Siafakas, Nikolaos Tzanakis, Georgios Meletis, Emmanouil Ntaoukakis, Aggeliki Damianaki, Konstantinos Kallergis, Georgios Hrysofakis, Spyros Logothetis, Kyriakos Hainis, Stylianos Podaras, Eleni Nikolopoulou, Panagiotis Kritis, Konstantinos Karkanis, Foivos Kokkinis, Christina Koumpaniou, Karmen Manta-Stahouli, Stavroula Ponirea, Nikolaos Harokopos, Nikolaos Galanis, Evangelia Fouka, Evangelia Serasli, Venetia Tsara, Lazaros Sihletidis, Marianna Kakoura, Stavros Vogiatzis, Anna Gavriilidou, Kleio Eleftheriou, Despoina Kosmidou, Vasiliki Dimitriadou, Dimitris Zois, Sotiria Laparidou, Antonios Antoniadis, Vasileios Ioannidis, Emmanouil Liolios, Stavroula Mpousmoukilia, Dimosthenis Mpouros, Georgios Patlakas, Efmorfia Tsiantou, Ignatios Katsenis, Thomas Arhontis, Athanasios Mitsios, Konstantinos Perifanos, Konstantinos Kostikas, Evridiki Karakasi, Ioannis Tsiotsios, Thoedoros Tsaias, Vasilis Adamidis, Damianos Damianakos, Anastasia Pella, Theofilos Pehlivanidis, Eleni Servakou, Panagiotis Hatziapostolou, Aikaterini Kazakou, Thomas Karapetsas, Prodromos Hatzivlasiou, Maria Katertzi – Moshoni, Stergios Pavlidis, Sotiria Sevastou, Foteini Simoglou, Stylianos Kaloudis, Iraklis Titopoulos, Ilias Tselepis, Hrysoula Kourtidou, Ioannis Tsimpoukelis, Dimitrios Zordinis, Iosif Elemenoglou, Efthimia papadopoulou, Stavros Tryfon, Alexandros Filandrianos, Vasiliki Tzelepi, Dimitra Theodoridou-Tsanaka, Eleni Thomoglou, Konstantinos Haritopoulos, Kosmas Papahristou, Apostolos Arvanitidis, Argyro Theodorikakou, Amalia Ferentinou, Aggelos Nikitas, Hristos Tzafaridis, Anastasia Samakovli, Ourania Georgoudi, Miltiadis Markatos, Grigorios Georgoudakis, Stylianos Kalogerakis, Panagiotis Mamatzakis, Konstantinos Hatzakis, Nikolaos Paterakis, Ioannis Politis, Evangelos Zigakis, Astrinos Ieronimakis, Mihalis Arvanitakis, Kalliopi Sigelaki, Marouso Stathppoulou, Evangelia Daniil, Mihail Psihakis, Nikolaos Karvounas, Georgios Kotrogiannis, Georgios Koulouris, Eleftherios Vrouvakis, Ifigeneia Topaka, Panagiotis Theodosiou, Eirini Savva, Alexandros Konstantinidis, Panagiotis Kokkonis, Christina Leontaridi, Stefania Katsoulidi, Vasiliki Lazou, Panagiota Ksilogianni, Stylianos Strakantounas, Vasileios Kyriakidis, Magda Gouni, Panagiota Traka, Alexandros Tsakatikas, Anastasia Spata, Lemonia Karoutsou, Nikolaos Svolis, Nikiforos Papatsimpas, Panagiotis Karkaletsis, Alexandros Kazamias, Sofia Alexandraki, Konstantinos Nikas, Emmanouil Tziralidis, Pantelis Avarlis, Mihail Sakellaropoulos, Dimitrios Fotopoulos, Georgios Nikolopoulos, Athanasios Aggelopoulos, Georgios Tsarouhis, Aglaia Skouta, Ioannis Laskaris, Panagiotis Kyriazis, Antonia Konsta, Panagiotis Koursarakos, Leonidas Stellas, Antonis Hristopoulos, Nikolaos Karatzas, Dionysios Papalexatos, Vasileios Topallianidis, Antionios Antoniadis, Gerasimos Apollonatos, Athanasia Sampani, Styliani Mytilinaiou, Eleni Fotopoulou, Ioannis Maragos, Antonios Kladogenis, Vasileios Konstantaras, Georgia Kotantoula, Theodoros Nikoloudis, Hara Kyriakaki, Nikolaos Malamos, Panagiota Hatzigiannaki, Eirini Koumpa, Dimosthenis Tsipilis, Christina Theohari, Eirini Daskalaki, Anna Kontogianni, Panagiotis Argyriou, Tziovani Termine, Fanis Giannakas, Lampros Lampropoulos, Olympia Chioni

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following pulmonary medicine physicians for their contribution to the study.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Eleni Bania, Eirini Mitsiki, Evangelos C Alexopoulos, and Konstantinos I Gourgoulianis were involved in the study conception and design. Andriana I Papaioannou contributed to study design and conception. Konstantinos I Gourgoulianis is the guarantor. Eleni Bania, Eirini Mitsiki and Foteini Malli collected the data. Evangelos C Alexopoulos performed the statistical analysis of the data. Andriana I Papaioannou, Eirini Mitsiki, Foteini Malli, and Evangelos C Alexopoulos prepared the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript, and read and approved the final version.

Disclosure

Andriana I Papaioannou and Foteini Malli have no conflicts of interest in relation to this article. Eleni Bania has worked for Novartis. Evangelos C Alexopoulos held a contract with Novartis for participating in the study design and performing the statistical analysis. Eirini Mitsiki is currently working for Novartis. Konstantinos I Gourgoulianis has received an investigator’s fee for the GOLDEN study by Novartis. The study was funded by Novartis Hellas. The authors report no further conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Thornton Snider J, Romley JA, Wong KS, Zhang J, Eber M, Goldman DP. The Disability burden of COPD. COPD. 2012;9(5):513–521. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2012.696159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Celli BR, MacNee W, ATS/ERS Task Force Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(6):932–946. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(6):532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2011. [Accessed December 7, 2013]. [website on the Internet]. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org.

- 5.Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al. BOLD Collaborative Research Group International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet. 2007;370(9589):741–750. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sichletidis L, Tsiotsios I, Gavriilidis A, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and rhinitis in northern Greece. Respiration. 2005;72(3):270–277. doi: 10.1159/000085368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tzanakis N, Anagnostopoulou U, Filaditaki V, Christaki P, Siafakas N, COPD group of the Hellenic Thoracic Society Prevalence of COPD in Greece. Chest. 2004;125(3):892–900. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.3.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minas M, Koukosias N, Zintzaras E, Kostikas K, Gourgoulianis KI. Prevalence of chronic diseases and morbidity in primary health care in central Greece: an epidemiological study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:252. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, Ford ES, Redd SC. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease surveillance – United States, 1971–2000. Respir Care. 2002;47(10):1184–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minas M, Hatzoglou C, Karetsi E, et al. COPD prevalence and the differences between newly and previously diagnosed COPD patients in a spirometry program. Prim Care Respir J. 2010;19(4):363–370. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2010.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sichletidis LT, Chloros D, Tsiotsios I, et al. High prevalence of smoking in Northern Greece. Prim Care Respir J. 2006;15(2):92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pcrj.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Torres JP, Casanova C, Hernández C, Abreu J, Aguirre-Jaime A, Celli BR. Gender and COPD in patients attending a pulmonary clinic. Chest. 2005;128(4):2012–2016. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez FJ, Curtis JL, Sciurba F, et al. National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group Sex differences in severe pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(3):243–252. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-828OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dransfield MT, Davis JJ, Gerald LB, Bailey WC. Racial and gender differences in susceptibility to tobacco smoke among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2006;100(6):1110–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shibuya K, Mathers CD, Lopez AD. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): consistent estimates of incidence, prevalence, and mortality by WHO region. Global Programme on Evidence for Health Policy. World Health Organization; 2001. [Accessed January 15, 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/bod_copd.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopez AD, Shibuya K, Rao C, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(2):397–412. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00025805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hellenic Statistical Authority [website on the Internet] [Accessed December 7, 2013]. Available from: http://www.statistics.gr/portal/page/portal/ESYE/PAGE-database.

- 18.Hellenic Thoracic Society [website on the Internet] [Accessed December 7, 2013]. Available from: http://www.hts.org.gr/ Greek.

- 19.Cheung YB. Zero-inflated models for regression analysis of count data: a study of growth and development. Stat Med. 2002;21(10):1461–1469. doi: 10.1002/sim.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurmi OP, Lam KB, Ayres JG. Indoor air pollution and the lung in low-and medium-income countries. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(1):239–254. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00190211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertakis KD, Azari R, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, Robbins JA. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(2):147–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rennard SI. Clinical approach to patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiovascular disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2(1):94–100. doi: 10.1513/pats.200410-051SF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nilsson M, Lundegårdh G, Carling L, Ye W, Lagergren J. Body mass and reflux oesophagitis: an oestrogen-dependent association? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37(6):626–630. doi: 10.1080/00365520212502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almagro P, Calbo E, Ochoa de Echagüen A, et al. Mortality after hospitalization for COPD. Chest. 2002;121(5):1441–1448. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miravitlles M, Guerrero T, Mayordomo C, Sánchez-Agudo L, Nicolau F, Segú JL. Factors associated with increased risk of exacerbation and hospital admission in a cohort of ambulatory COPD patients: a multiple logistic regression analysis. The EOLO Study Group. Respiration. 2000;67(5):495–501. doi: 10.1159/000067462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vikum E, Krokstad S, Westin S. Socioeconomic inequalities in health care utilisation in Norway: the population-based HUNT3 survey. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11:48. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rabe KF, Fabbri LM, Vogelmeier C, et al. Seasonal distribution of COPD exacerbations in the Prevention of Exacerbations with Tiotropium in COPD trial. Chest. 2013;143(3):711–719. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]