Abstract

Background

Long-term inhibition of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) by L-arginine analogues such as Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) has been shown to induce senescence in vitro and systemic hypertension and arteriosclerosis in vivo. We previously reported that PAI-1-deficient mice (PAI-1−/−) are protected against L-NAME-induced pathologies. In this study, we investigated whether a novel, orally active PAI-1 antagonist (TM5441) has a similar protective effect against L-NAME treatment. Additionally, we studied whether L-NAME can induce vascular senescence in vivo and investigated the role of PAI-1 in this process.

Methods and Results

Wild-type (WT) mice received either L-NAME or L-NAME and TM5441 for 8 weeks. Systolic blood pressure was measured every 2 weeks. We found that TM5441 attenuated the development of hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy compared to animals that had received L-NAME alone. Additionally, TM5441-treated mice had a 34% reduction in periaortic fibrosis relative to animals on L-NAME alone. Finally, we investigated the development of vascular senescence by measuring p16Ink4a expression and telomere length in aortic tissue. We found that L-NAME increased p16Ink4a expression levels and decreased telomere length, both of which were prevented with TM5441 co-treatment.

Conclusions

Pharmacological inhibition of PAI-1 is protective against the development of hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, and periaortic fibrosis in mice treated with L-NAME. Furthermore, PAI-1 inhibition attenuates the arterial expression of p16Ink4a and maintains telomere length. PAI-1 appears to play a pivotal role in vascular senescence, and these findings suggest that PAI-1 antagonists may provide a novel approach in preventing vascular aging and hypertension.

Keywords: hypertension, aging, nitric oxide synthase

Introduction

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is an enzyme that catalyzes the formation of nitric oxide (NO) from L-arginine. NO is an important signaling molecule that is involved in a variety of physiological processes,1 most notably the regulation of vascular tone and structure. By stimulating the production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) in vascular smooth muscle cells surrounding blood vessels, NO causes muscle relaxation and a decrease in blood pressure.2 Additionally, NO has atheroprotective, anti-thrombotic, and anti-inflammatory properties through its ability to inhibit platelet aggregation, expression of adhesion molecules, and lipid oxidation.2 Mice lacking expression of eNOS lose the ability to produce vascular NO, and as a result develop hypertension.3, 4 Similar results are also seen when NOS activity is blocked by the competitive inhibitor Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME).5-7 NO also has important biological functions outside of the vasculature, including roles in the gastrointestinal, respiratory, nervous, and immune systems.2

It has been reported that NO suppresses the expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) in vascular smooth muscle cells.8 Similarly, long-term inhibition of NOS in rats by L-NAME treatment resulted in increased vascular PAI-1 expression.9 PAI-1 is the primary physiological inhibitor of plasminogen activation and is a member of the SERPIN superfamily of serine protease inhibitors.10 In plasma, PAI-1 has a critical role in regulating endogenous fibrinolytic activity and resistance to thrombolysis. In vascular tissues, PAI-1 mediates the response to injury by inhibiting cellular migration11 and matrix degradation.12 Additionally, substantial evidence exists showing that PAI-1 may contribute to the development of fibrosis and thrombosis due to chemical13 or ionizing injury.14 In the absence of vascular injury or hyperlipidemia, our group has reported that transgenic mice overexpressing a stable form of human PAI-1 develop spontaneous coronary arterial thrombosis.15

We have also previously reported that PAI-I deficiency prevents the development of perivascular fibrosis associated with long-term NOS inhibition by L-NAME.16, 17 In the present study, we demonstrate that a novel, orally active small molecule inhibitor of PAI-1, TM5441, is as effective as complete deficiency of PAI-1 in protecting against L-NAME-induced pathologies. TM5441 is a derivative of the previously reported PAI-1 inhibitor TM5275,18 which was generated by optimizing the structure-activity relationships of the lead compound TM5007.19 TM5007 was originally identified as a PAI-1 inhibitor by virtual, structure-based drug design which used a docking simulation to select candidates that fit within a cleft in the 3-dimensional structure of human PAI-1.

Beyond examining PAI-1 in L-NAME-induced arteriosclerosis, the present study focuses on the roles of NO and PAI-1 in vascular senescence. Senescent endothelial cells exhibit reduced eNOS activity and NO production,20, 21 and NO has been shown to be protective against the development of senescence, an effect that is abrogated by L-NAME treatment.22, 23 However, the role of NO and L-NAME in vascular senescence in vivo is uncertain. PAI-1 is recognized as a marker of senescence and is a key member of a group of proteins collectively known as the senescence-messaging secretome (SMS).24 However, it is likely that PAI-1 is not just a biomarker of senescence, but instead may be a critical driver of this process. Evidence supporting this hypothesis has already been shown in vitro. PAI-1 expression is both necessary and sufficient to drive senescence in vitro downstream of p53, and PAI-1-deficient murine embryonic fibroblasts are resistant to replicative senescence.25, 26 However, very little is known about the role of PAI-1 in senescence in vivo.

In this study, we show that L-NAME treatment and the subsequent loss of NO production induces vascular senescence in wild-type (WT) mice, and that treatment with the PAI-1 antagonist TM5441 is protective against this senescence. Therefore, in addition to validating TM5441 as a potential therapeutic, we also have demonstrated a role for L-NAME, NO, and PAI-1 in vascular senescence in vivo.

Methods

TM5441 Activity and Specificity Assays

The inhibitory activity and specificity of TM5441 (developed at the United Centers for Advanced Research and Translational Medicine (ART), Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, Miyagi, Japan) was assessed using recombinant PAI-1, antithrombin III, and α2-antiplasmin by chromogenic assay as previously described.27, 28 The reaction mixture includes 0.15 mol/L NaCl, 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl pH8, 0.2mmol/L CHAPS, 0.1% PEG-6000, 1% dimethylsulfoxide, 5 nmol/L of either human active PAI-1 (Molecular Innovations, Southfield, MI), human antithrombin III (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) or human α2-antiplasmin (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 nmol/L of either human 2-chain tPA (American Diagnostica Inc., Stanford, CT), thrombin (Sigma-Aldrich) or plasmin (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.2 mmol/L of either Spectrozyme tPA (Chromogenix, Milano, Italy), chromogenic substrate S-2238 (Sekisui medical, Tokyo, Japan), or chromogenic substrate S-2251 (Sekisui medical) at a final concentration. Tested compounds were added at various concentrations and the IC50 was calculated by the logit-log analysis.

TM5441 Pharmacokinetics and Toxicity

TM5441, suspended in a 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose sodium salt (CMC) solution, was administered orally by gavage feeding to male Wistar rats (5 mg/kg) (CLEA Japan Inc.). Heparinized blood samples were collected from the vein before (0 h) and 1, 2, 6, and 24 h after oral drug administration. Plasma drug concentration was determined on a reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Maximum drug concentration time (Tmax), maximum drug concentration (Cmax), and drug half-life (T1/2) were then calculated.

All toxicity studies followed the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Harmonised Tripartite Guidelines at the non-GLP conditions. A repeated-dose toxicity study of TM5441 was assessed for 2 weeks in 5 Crl:CD (SD) rats per sex per group and no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) was concluded at 30 mg/kg in female rats and 100 mg/kg in male rats. As for the reverse mutation Ames test, TM5441 was negative. The effect of TM5441 on hERG electric current was investigated in HEL293 cells, which were transfected with the hERG gene, and TM5441 does not affect on hERG electric current in a concentration of up to 10 mM.

Experimental Animals

Studies were performed on littermate 6-8 week old C57BL/6J mice of both sexes purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). L-NAME (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was administered in the drinking water at 1 mg/mL (approximately 100-120 mg/kg/day). TM5441 was mixed in the chow at a concentration of 20 mg/kg/day. This dose was based on both preliminary studies conducted in our laboratory feeding mice with TM5441 and on personal communication with Dr Miyata. The weight of chow consumed by the mice and their body weight were monitored. Mice remained in the study for 8 weeks before undergoing final measurements and tissue harvest. All experimental protocols were approved by the IACUC of Northwestern University.

Blood Pressure

Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured in conscious mice (n=12-13/group) at baseline and every 2 weeks thereafter using a non-invasive tail-cuff device (Volume Pressure Recording, CODA, Kent Scientific Corp, Torrington, CT). Mice were placed in the specialized holder for 10-15 minutes prior to the measurement in order to acclimate to their surroundings. The animals underwent 3 training sessions prior to initial baseline measurements. This method has been validated against classic tail plethysmography.

Echocardiograms

Left ventricular function at diastole was determined in the mice (n=12-13/group) with the use of two-dimensional (2D), M, and Doppler modes of echocardiography (Vevo 770, Visualsonics Inc., Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Mice were imaged at both baseline and after 8 weeks of treatment. The animals were anesthetized and placed supine on a warming platform. Parasternal long- and short-axis views were obtained in each mode to assess function.

Histology and Morphometry

Hearts and aortas were harvested from the animals after 8 weeks of treatment. The tissues were formalin fixed, paraffin embedded, and sectioned at 6 microns. Morphometric analysis was performed on left ventricular myocytes stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) in order to calculate myocyte cross-sectional area using ImagePro Plus 6.3. Myoyctes that had a clear, unbroken cellular membrane and a visible nucleus were cut transversely, traced, and the areas determined. Approximately 100 myocytes were counted per mouse (n=12-13/group).

Morphometric analysis was also performed on aortic sections stained with Masson's trichome in order to calculate the extent of perivascular fibrosis. The aorta and its surrounding collagen layer were traced, and the extent of fibrosis calculated by determining the percentage of the total area occupied by collagen (stained blue) (n=10-12/group).

qRT-PCR

Aortas harvested from subject mice were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen (n=6-11/group). Excess tissue was removed under a dissecting microscope. RNA was isolated using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) using the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was generated from the RNA using the qScript cDNA Supermix (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the SsoAdvanced SYBR Green Supermix (Biorad, Hercules, CA) along with primers for PAI-1 (F: 5’-ACGCCTGGTGCTGGTGAATGC-3’ and R: 5’-ACGGTGCTGCCATCAGACTTGTG-3’), p16Ink4a (F: 5’-AGGGCCGTGTGCATGACGTG-3’ and R: 5’-GCACCGGGCGGGAGAAGGTA-3’), and GAPDH (F: 5’-ATGTTCCAGTATGACTCCACTCACG-3’ and R: 5’-GAAGACACCAGTAGACTCCACGACA-3’) (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Coralville, IA).

Average Telomere Length Ratio Quantification

Aortas and livers harvested from subject mice were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen (n=6-11/group). Excess tissue was removed under a dissecting microscope. Genomic DNA was isolated using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) by following the manufacturer's protocol, and then was used to measure telomere length by quantitative real-time PCR as previously described with minor modification.29, 30 Briefly, telomere repeats are amplified using specially designed primers, which are then compared to the amplification of a single-copy gene, the 36B4 gene (acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein PO), to determine the average telomere length ratio (ATLR). Either 15 ng (aortas) or 100 ng (livers) of genomic DNA template was added to each 20 μl reaction containing forward and reverse primers (250 nM each for telomere primers, and 500 nM each for the 36B4 primers), SsoAdvanced SYBR Green Supermix (Biorad, Hercules, CA), and nuclease free water. A serially diluted standard curve of 25 ng to 1.5625 ng (aortas) or 100 ng to 3.125 ng (livers) per well of template DNA from a WT mouse sample was included on each plate for both the telomere and the 36B4 reactions to facilitate ATLR calculation. Ct values were converted to ng values according to the standard curves, and ng values of the telomere (T) reaction were divided by the ng values of the 36B4 (S) reaction to yield the ATLR. The primer sequences for the telomere portion were as follows: 5’-CGGTTTGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTT-3’ and 5’-GGCTTGCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCT-3’. The primer sequences for the 36B4 single copy gene portion were as follows: 5’-ACTGGTCTAGGACCCGAGAAG-3’ and 5’-TCAATGGTGCCTCTGGAGATT-3’. Cycling conditions for both primer sets (run in the same plate) were: 95 °C for 10 min, 30 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, and 55 °C for 1 min for annealing and extension.

Statistical Analysis

All results are presented as mean ± SD. Comparisons between 2 groups were tested by an unpaired, 2-tailed Student's t test (unless otherwise noted). Results with P≤0.05 were considered significant.

Expanded methods and materials are in Supplemental Data.

Results

Generation and Validation of TM5441

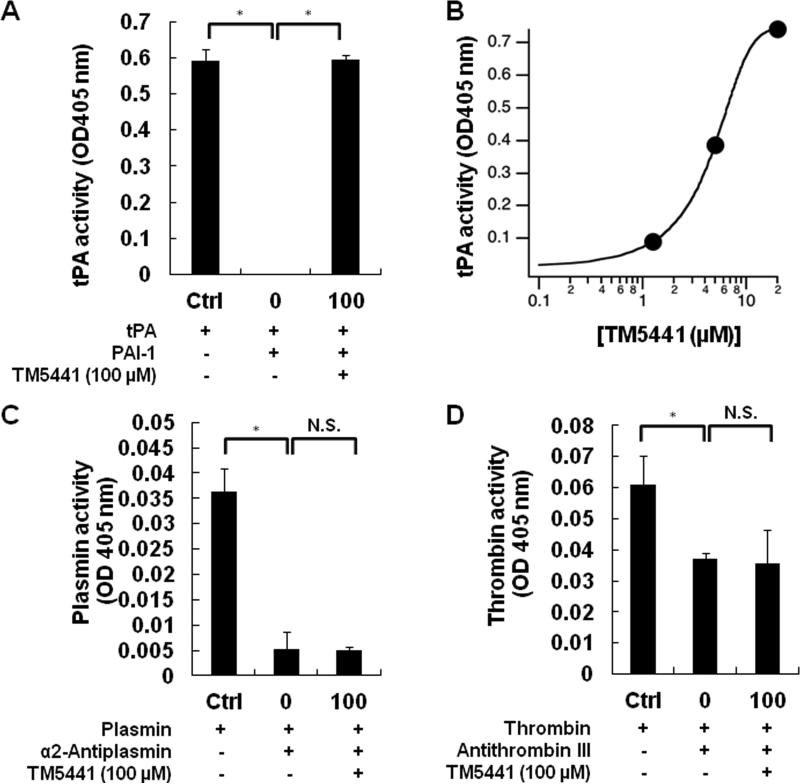

TM5441 (molecular weight, 428.8 g/mol; cLogP, 3.319) was discovered through an extensive structure-activity relationship study with more than 170 novel derivatives with comparatively low molecular weights (400 to 550 g/mol) and without symmetrical structure, designed on the basis of the original lead compound TM500719 and an already successful modified version, TM5275.18 TM5007 was identified virtually by structure-based drug design after undergoing a docking simulation that selected for compounds that fit within the cleft of PAI-1 (s3A in the human PAI-1 3-dimensional structure) accessible to insertion of the reactive center loop (RCL). Compounds that bind in this cleft would block RCL insertion and thus prevent PAI-1 activity. Once TM5007 had been identified as a PAI-1 inhibitor both virtually and in vitro/in vivo, further compounds were derived via chemical modification in order to improve the pharmacokinetic properties of the inhibitor, resulting in the generation of TM5275 and later TM5441 (Table 1). The inhibitory activity of TM5441 was shown in vitro by a chromogenic assay (Figure 1A and B) and its specificity was confirmed by demonstrating that it did not inhibit other SERPINs such as antithrombin III (Figure 1C) and α2-antiplasmin (Figure 1D).

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic properties of PAI-1 inhibitors

| Inhibitor | Oral dose in rat | Cmax (μM)† | Tmax (h)‡ | T1/2 (h)§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TM500718 | 50 mg/kg | 8.8 | 18 | 124 |

| TM527518 | 50 mg/kg | 34 | 2 | 2.5 |

| TM5441 | 5 mg/kg | 17.9 | 1 | 2.3 |

maximum concentration achieved after administration

time until maximum concentration is achieved

half-life in circulation

Figure 1.

TM5441 specifically inhibits PAI-1. (A and B) TM5441 inhibited the PAI-1 activity in a dose dependent manner, but did not modify other SERPIN/serine protease systems such as (C) α2-antiplasmin/plasmin and (D) antithrombin III/thrombin. Data are mean ± SD. *P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's test. n=3. N.S., not significant; tPA, tissue plasminogen activator.

TM5441 Attenuates the Effects of L-NAME on Systolic Blood Pressure

6-8 week old WT C57BL/6J animals were given either L-NAME (1 mg/mL) water or regular water for 8 weeks. Additionally, animals received either TM5441 (20 mg/kg/day) chow or regular diet. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) was measured every 2 weeks over the course of the study. As shown in Figure 2A, animals given L-NAME in their drinking water for 8 weeks had a 35% increase in SBP compared to WT animals receiving untreated water (183 ± 13 mmHg vs. 135± 16 mmHg, P=3.1×10−7). However, animals receiving both L-NAME and the PAI-1 inhibitor TM5441 had significantly lower SBPs compared to those that received L-NAME alone (163 ± 21 mmHg vs.183 ± 13 mmHg, P=0.009). This difference in SBP between L-NAME and L-NAME + TM5441 animals was similar to previously reported data comparing L-NAME-treated WT and PAI-1-deficient mice.16, 17 Thus, we confirmed that pharmacologic inhibition of PAI-1 activity using the novel antagonist TM5441 protects against L-NAME-induced hypertension to a similar degree as the full genetic knockout. As a control, we also looked at animals receiving only TM5441 in order to show that the drug had no off-target effects on SBP. These animals showed no difference in SBP compared to WT. Additionally, using LC/MS/MS, we confirmed the presence of TM5441 in the plasma of our co-treated animals and showed that the concentration of TM5441 correlated slightly with SBP (Supplemental Figure 1).

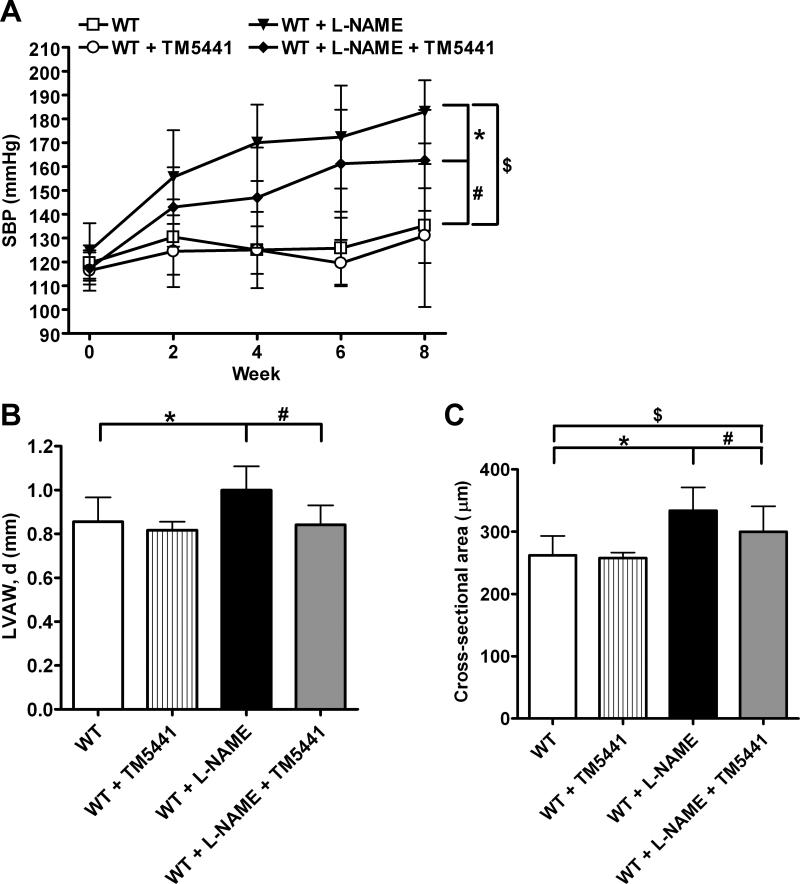

Figure 2.

The effect of L-NAME and TM5441 on hypertension and hypertrophy. (A) SBP was measured throughout the course of the study every 2 weeks. *P=0.009, #P=0.001, $P=3.1×10−7. (B) Echocardiograms were performed on 8 week old mice before sacrifice. Left ventricle anterior wall thickness (LVAW) was measured at diastole. *P=0.006, #P=0.002. (C) Left ventricles were cross-sectioned and stained using hematoxylin and eosin. Approximately 100 transversely cut myocytes per mouse were traced and cross-sectional area was quantified. *P=0.04, #P=0.00003, $P=0.01. Data are mean ± SD. n=12-13.

TM5441 Reduces Cardiac Hypertrophy Derived from L-NAME Treatment

As seen in Figure 2B, L-NAME-treated animals showed a significant thickening of their left ventricle anterior wall (LVAW) during diastole relative to WT (1.00 ± 0.11 mm vs. 0.86 ± 0.11 mm, P=0.006). PAI-1 antagonism attenuated LVAW thickness compared to L-NAME treatment alone (0.84 ± 0.09 mm vs. 1.00 ± 0.11 mm, P=0.002). This reduction in cardiac hypertrophy was seen at the cellular level as well (Figure 2C). Left ventricle myocyte cross-sectional area significantly increased in WT + L-NAME mice compared to WT (334 ± 37 μm2 vs. 262 ± 31 μm2, P=0.00003), but co-treatment with TM5441 reduced the extent of hypertrophy compared to L-NAME treatment alone (300 ± 42 μm2 vs. 334 ± 37 μm2, P=0.04). Animals receiving only TM5441 were not significantly different from WT in either measurement.

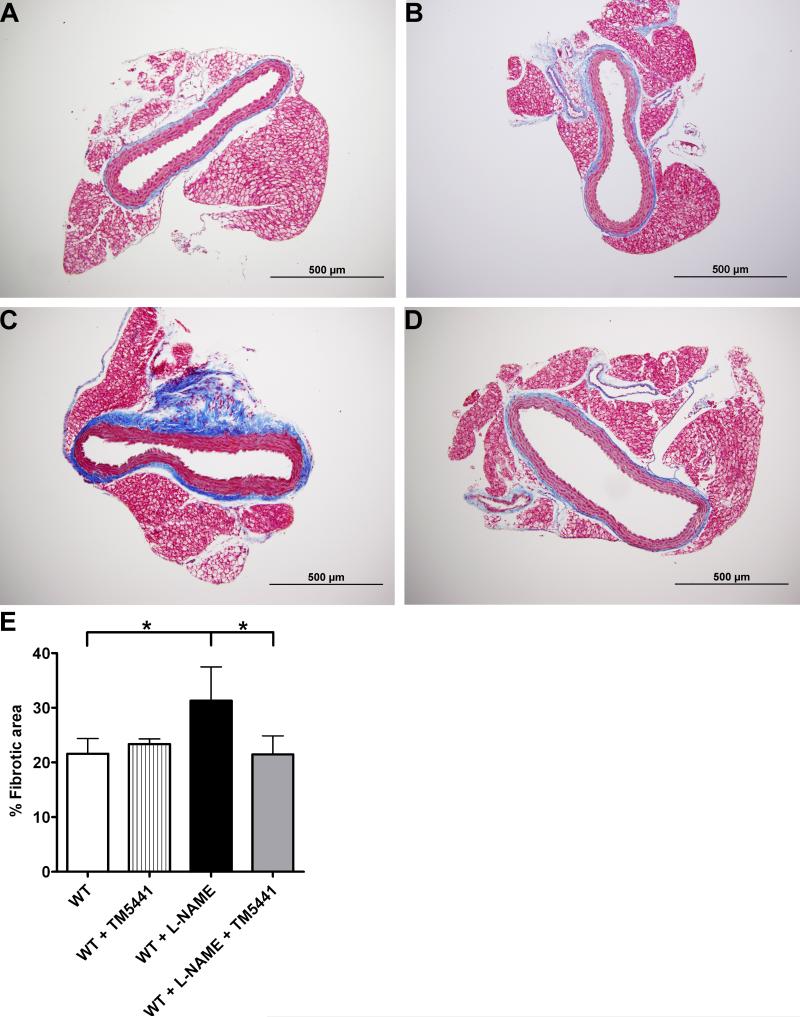

TM5441 Prevents the Development of Periaortic Fibrosis

Cross-sections from the aorta were stained with Masson's trichome to examine the extent of perivascular fibrosis. As shown in Figure 3, the ratio of fibrotic area compared to total vascular area was significantly increased in L-NAME-treated animals compared to WT (31 ± 6 % vs. 22 ± 3%, P=0.0006). However, co-administration of TM5441 with L-NAME prevented collagen accumulation around the aorta so that these animals maintained a baseline level of fibrosis (22 ± 3% vs. 32 ± 6% for WT + L-NAME, P=0.0006). Thus, PAI-1 inhibition prevents the structural remodeling of the vasculature associated with L-NAME treatment.

Figure 3.

TM5441 attenuates L-NAME-induced periaortic fibrosis. Cross-sections of the aorta were sectioned and stained with Masson's trichome to evaluate the extent of fibrosis in (A) WT, (B) WT + TM5441, (C) WT + L-NAME, and (D) WT + L-NAME + TM5441 mice. Blue staining indicates the presence of collagen. (E) The ratio of fibrotic to total vascular area was calculated. *P=0.006. Data are mean ± SD. n=10-12.

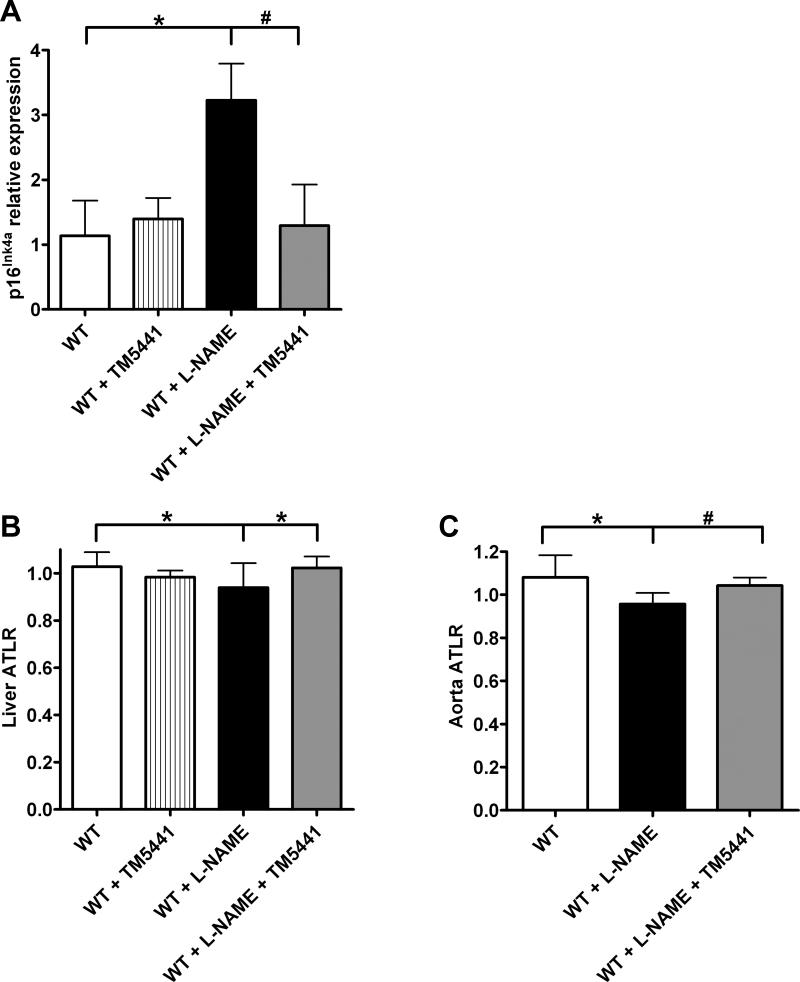

TM5441 Protects Against L-NAME-Induced Vascular Senescence

Previous in vitro work has demonstrated that the loss of NO through L-NAME treatment can lead to endothelial cell senescence.22, 23 In this study, we determined the level of senescence in vivo in aortas using quantitative RT-PCR. When examining the senescence marker p16Ink4a, we found that while L-NAME treatment significantly increased the expression of p16Ink4a three-fold (P=0.008 vs. WT), this increase was prevented by TM5441 co-treatment (P=0.01 vs. WT + L-NAME) (Figure 4A). We confirmed these results by using a PCR method to measure average telomere length ratio (ATLR) in both liver (Figure 4B) and aorta (Figure 4C). 29, 30 In both tissues, L-NAME significantly reduced telomere length, whereas those animals receiving L-NAME and TM5441 had no change in telomere length relative to WT animals.

Figure 4.

L-NAME induces vascular senescence. (A) Expression levels of p16Ink4a mRNA normalized to GAPDH. *P=0.008 #P=0.01. Average telomere length ratio (ATLR) for (B) livers and (C) aortas. (B) *P-0.02 (C) *P=0.01 #P=0.003. Data are mean ± SD. n=6-11.

Discussion

Long-term NOS inhibition leads to hypertension through the combination of the loss of NO-dependent vasodilation and arteriosclerotic remodeling of the vasculature.5-7 Similar to previously reported data,16, 17 in the present study SBP increased after only 2 weeks of L-NAME treatment and continued to rise throughout the study. However, when the animals were simultaneously treated with L-NAME and the PAI-1 inhibitor TM5441, the increase in SBP was blunted. This reduction in SBP is similar to that seen previously with PAI-1-deficient mice,16, 17 indicating that TM5441 is effective in minimizing the effects of L-NAME on SBP. These results correlate with our previous observations that loss of PAI-1 is protective against angiotensin II-induced hypertension (Supplemental Figure 2), thus demonstrating that the effect of PAI-1 on SBP is NO-independent. To our knowledge, this is the first instance of a non-anti-hypertensive drug successfully preventing systolic hypertension.

Left ventricular hypertrophy is a common consequence of hypertension. Accordingly, we used echocardiography and histology to evaluate the left ventricle in the experimental animals. L-NAME caused significant increases in both wall thickness and myocyte cross-sectional area. TM5441 treatment reduced these compensatory responses by 16% and 10%, respectively. This reduction in hypertrophy further demonstrates that PAI-1 inhibition effectively protects against hypertension and its associated pathologies.

In addition to the changes in blood pressure, we directly examined the changes in vascular remodeling caused by L-NAME by quantifying the extent of periaortic fibrosis in these animals. L-NAME-treated mice had almost 50% more fibrosis surrounding their aortas as compared to the aortas from untreated WT. This increase was completely attenuated in animals receiving both L-NAME and TM5441, as these mice had identical levels of fibrosis to that observed in untreated WT controls. Excess PAI-1 is known to exacerbate the development of fibrosis in a variety of animal models,31, 32 and L-NAME elevates arterial PAI-1 expression.9 Furthermore, we have previously shown that PAI-1 deficiency both augments gelatinolytic activity in coronary arteries using in situ zymography17 and protects against periaortic fibrosis induced by angiotensin II.33 Taken together, this data identifies a mechanism through which PAI-1 deficiency is protective against collagen deposition and perivascular fibrosis. Thus, we would anticipate both the structural changes seen in the L-NAME-treated aortas and the protection against these changes provided by TM5441.

The capacity of TM5441 to prevent the increase in SBP and reduce the development of hypertrophy and arteriosclerosis makes it a promising therapeutic, particularly in the elderly population where arteriosclerosis likely makes a major contribution to this common malady. Even though TM5441 treatment did not fully attenuate the increase in SBP due to NOS inhibition, the almost complete prevention of periaortic fibrosis indicates that PAI-1 inhibition is a novel approach to combat the structural remodeling in clinical situations and conditions associated with reduced NO production or bioavailability.

Loss of NO production has been shown to induce vascular senescence in vitro,22, 23 and increased PAI-1 is an established as a marker of senescence.24, 25 However, little work has been done to examine the role of NO in senescence in vivo. We determined that NOS inhibition can induce senescence in vivo by showing that L-NAME-treated aortas had a three-fold increase in expression of the senescence marker p16Ink4a relative to WT controls. More importantly, we wanted to establish that PAI-1 is not just a marker of senescence, but rather is a critical driver of this process in vivo. This was confirmed by demonstrating that aortic p16Ink4a levels in mice treated with both L-NAME and TM5441 were comparable to those seen in WT controls. This observation is in agreement with other data from this laboratory indicating that partial or complete deficiency of PAI-1 in the klotho mouse model is sufficient to prevent senescence and prolong survival (Mesut Eren, PhD, manuscript under review). Telomere length, another well-established cellular marker of physiological aging, was also examined in both aortic and hepatic tissues. We chose to examine the liver because it is a highly vascularized organ and has been previously shown to be affected by L-NAME.34 Both aortas and livers from L-NAME-treated animals showed significant decreases in ATLR that reflect the induction of senescence and accelerated aging. In both organs, co-treatment of L-NAME with TM5441 was able to maintain telomere length similar to WT levels.

The present study establishes PAI-1 as an important determinant of vascular senescence in vivo. Additionally, it is possible that all the pathological conditions developed in the L-NAME-treated animals (hypertension, perivascular fibrosis, and hypertrophy) could be secondary effects from the induction of vascular senescence. This is further supported by the fact that age is the single greatest risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD).35, 36 PAI-1 expression is known to be both elevated in the elderly and in many conditions associated with aging such as obesity, insulin resistance, and vascular remodeling.37 Furthermore, NO production has been shown to decrease with age, even in healthy individuals.38 Combined with the data shown here, these findings indicate that age-related decreases in NO production can lead to vascular senescence and arteriosclerosis, and that this process may be prevented through PAI-1 inhibition. These findings certainly suggest that PAI-1 antagonists may eventually prove to be useful in preventing hypertension as well as protecting against the increased risk in CVD that accompanies aging.

In conclusion, we have shown that TM5441, a novel, orally active PAI antagonist, protects mice against L-NAME-induced vascular pathologies, including hypertension, fibrosis, and vascular senescence. TM5441 represents a novel therapeutic approach for the aging-associated cardiovascular disease that merits further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Marissa Michaels, MS for her help in obtaining reagents and Aaron Place, PhD and Varun Nagpal, MS for reviewing the manuscript.

Funding Sources: This work was supported by NIH/NHLBI 2R01 HL051387 and 1P01HL108795.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Knowles RG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide synthases in mammals. Biochem J. 1994;298(Pt 2):249–258. doi: 10.1042/bj2980249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feletou M, Kohler R, Vanhoutte PM. Nitric oxide: Orchestrator of endothelium-dependent responses. Ann Med. 2012;44:694–716. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.585658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang PL, Huang Z, Mashimo H, Bloch KD, Moskowitz MA, Bevan JA, Fishman MC. Hypertension in mice lacking the gene for endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nature. 1995;377:239–242. doi: 10.1038/377239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shesely EG, Maeda N, Kim HS, Desai KM, Krege JH, Laubach VE, Sherman PA, Sessa WC, Smithies O. Elevated blood pressures in mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc. Natl Acad Sci. USA. 1996;93:13176–13181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zatz R, Baylis C. Chronic nitric oxide inhibition model six years on. Hypertension. 1998;32:958–964. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.6.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baylis C, Mitruka B, Deng A. Chronic blockade of nitric oxide synthesis in the rat produces systemic hypertension and glomerular damage. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:278–281. doi: 10.1172/JCI115849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribeiro MO, Antunes E, de Nucci G, Lovisolo SM, Zatz R. Chronic inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis. A new model of arterial hypertension. Hypertension. 1992;20:298–303. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.20.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouchie JL, Hansen H, Feener EP. Natriuretic factors and nitric oxide suppress plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Role of cgmp in the regulation of the plasminogen system. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:1771–1779. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.11.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katoh M, Egashira K, Mitsui T, Chishima S, Takeshita A, Narita H. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor prevents plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression in a rat model with cardiovascular remodeling induced by chronic inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:73–83. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaughan DE. Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1: Molecular aspects and clinical importance. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 1995;2:187–193. doi: 10.1007/BF01062709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stefansson S, Lawrence DA. The serpin pai-1 inhibits cell migration by blocking integrin alpha v beta 3 binding to vitronectin. Nature. 1996;383:441–443. doi: 10.1038/383441a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heymans S, Luttun A, Nuyens D, Theilmeier G, Creemers E, Moons L, Dyspersin GD, Cleutjens JP, Shipley M, Angellilo A, Levi M, Nube O, Baker A, Keshet E, Lupu F, Herbert JM, Smits JF, Shapiro SD, Baes M, Borgers M, Collen D, Daemen MJ, Carmeliet P. Inhibition of plasminogen activators or matrix metalloproteinases prevents cardiac rupture but impairs therapeutic angiogenesis and causes cardiac failure. Nat Med. 1999;5:1135–1142. doi: 10.1038/13459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olman MA, Mackman N, Gladson CL, Moser KM, Loskutoff DJ. Changes in procoagulant and fibrinolytic gene expression during bleomycin-induced lung injury in the mouse. J Clin. Invest. 1995;96:1621–1630. doi: 10.1172/JCI118201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oikawa T, Freeman M, Lo W, Vaughan DE, Fogo A. Modulation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in vivo: A new mechanism for the anti-fibrotic effect of renin-angiotensin inhibition. Kidney Int. 1997;51:164–172. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eren M, Painter CA, Atkinson JB, Declerck PJ, Vaughan DE. Age-dependent spontaneous coronary arterial thrombosis in transgenic mice that express a stable form of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Circulation. 2002;106:491–496. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000023186.60090.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaikita K, Fogo AB, Ma L, Schoenhard JA, Brown NJ, Vaughan DE. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 deficiency prevents hypertension and vascular fibrosis in response to long-term nitric oxide synthase inhibition. Circulation. 2001;104:839–844. doi: 10.1161/hc3301.092803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaikita K, Schoenhard JA, Painter CA, Ripley RT, Brown NJ, Fogo AB, Vaughan DE. Potential roles of plasminogen activator system in coronary vascular remodeling induced by long-term nitric oxide synthase inhibition. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:617–627. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Izuhara Y, Yamaoka N, Kodama H, Dan T, Takizawa S, Hirayama N, Meguro K, van Ypersele de Strihou C, Miyata T. A novel inhibitor of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 provides antithrombotic benefits devoid of bleeding effect in nonhuman primates. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:904–912. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izuhara Y, Takahashi S, Nangaku M, Takizawa S, Ishida H, Kurokawa K, van Ypersele de Strihou C, Hirayama N, Miyata T. Inhibition of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1: Its mechanism and effectiveness on coagulation and fibrosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:672–677. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.157479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato I, Morita I, Kaji K, Ikeda M, Nagao M, Murota S. Reduction of nitric oxide producing activity associated with in vitro aging in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cell. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;195:1070–1076. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsushita H, Chang E, Glassford AJ, Cooke JP, Chiu CP, Tsao PS. Enos activity is reduced in senescent human endothelial cells: Preservation by htert immortalization. Circul Res. 2001;89:793–798. doi: 10.1161/hh2101.098443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayashi T, Matsui-Hirai H, Miyazaki-Akita A, Fukatsu A, Funami J, Ding QF, Kamalanathan S, Hattori Y, Ignarro LJ, Iguchi A. Endothelial cellular senescence is inhibited by nitric oxide: Implications in atherosclerosis associated with menopause and diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17018–17023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607873103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhong W, Zou G, Gu J, Zhang J. L-arginine attenuates high glucose-accelerated senescence in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuilman T, Peeper DS. Senescence-messaging secretome: Sms-ing cellular stress. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:81–94. doi: 10.1038/nrc2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kortlever RM, Higgins PJ, Bernards R. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is a critical downstream target of p53 in the induction of replicative senescence. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:877–884. doi: 10.1038/ncb1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elzi DJ, Lai Y, Song M, Hakala K, Weintraub ST, Shiio Y. Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1--insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 cascade regulates stress-induced senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12052–12057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120437109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Izuhara Y, Takahashi S, Nangaku M, Takizawa S, Ishida H, Kurokawa K, van Ypersele de Strihou C, Hirayama N, Miyata T. Inhibition of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1: Its mechanism and effectiveness on coagulation and fibrosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:672–677. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.157479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Izuhara Y, Yamaoka N, Kodama H, Dan T, Takizawa S, Hirayama N, Meguro K, van Ypersele de Strihou C, Miyata T. A novel inhibitor of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 provides antithrombotic benefits devoid of bleeding effect in nonhuman primates. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:904–912. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative pcr. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Callicott RJ, Womack JE. Real-time pcr assay for measurement of mouse telomeres. Comp Med. 2006;56:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eitzman DT, McCoy RD, Zheng X, Fay WP, Shen T, Ginsburg D, Simon RH. Bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in transgenic mice that either lack or overexpress the murine plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:232–237. doi: 10.1172/JCI118396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eren M, Gleaves LA, Atkinson JB, King LE, Declerck PJ, Vaughan DE. Reactive site-dependent phenotypic alterations in plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 transgenic mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1500–1508. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weisberg AD, Albornoz F, Griffin JP, Crandall DL, Elokdah H, Fogo AB, Vaughan DE, Brown NJ. Pharmacological inhibition and genetic deficiency of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 attenuates angiotensin ii/salt-induced aortic remodeling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:365–371. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000152356.85791.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith LH, Dixon JD, Stringham JR, Eren M, Elokdah H, Crandall DL, Washington K, Vaughan DE. Pivotal role of pai-1 in a murine model of hepatic vein thrombosis. Blood. 2006;107:132–134. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Najjar SS, Scuteri A, Lakatta EG. Arterial aging: Is it an immutable cardiovascular risk factor? Hypertension. 2005;46:454–462. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000177474.06749.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jousilahti P, Vartiainen E, Tuomilehto J, Puska P. Sex, age, cardiovascular risk factors, and coronary heart disease: A prospective follow-up study of 14 786 middle-aged men and women in finland. Circulation. 1999;99:1165–1172. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.9.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto K, Takeshita K, Kojima T, Takamatsu J, Saito H. Aging and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (pai-1) regulation: Implication in the pathogenesis of thrombotic disorders in the elderly. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lyons D, Roy S, Patel M, Benjamin N, Swift CG. Impaired nitric oxide-mediated vasodilatation and total body nitric oxide production in healthy old age. Clin Sci (Lond) 1997;93:519–525. doi: 10.1042/cs0930519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.