Abstract

Rationale

Perinatal exposure of rats to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) produces sensory and social abnormalities paralleling those seen in Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD). However, the possible mechanism(s) by which this exposure produces behavioral abnormalities is unclear.

Objective

We hypothesized that the lasting effects of neonatal SSRI exposure are a consequence of abnormal stimulation of 5-HT1A and/or 5-HT1B receptors during brain development. We examined whether such stimulation would result in lasting sensory and social deficits in rats in a manner similar to SSRIs using both direct agonist stimulation of receptors as well as selective antagonism of these receptors during SSRI exposure.

Methods

Male and female rat pups were treated from postnatal day 8 to 21. In Experiment 1, pups received citalopram (20mg/kg/d), saline, 8-OH-DPAT (0.5 mg/kg/d) or CGS-12066B (10 mg/kg/d). In Experiment 2, a separate cohort of pups received an citalopram (20 mg/kg/d), or saline which was combined with either WAY-100635 (0.6 mg/kg/d) or GR-127935 (6 mg/kg/d) or vehicle. Rats were then tested in paradigms designed to assess sensory and social response behaviors at different time points during development.

Results

Direct and indirect neonatal stimulation of 5-HT1A or 5-HT1B receptors disrupts sensory processing, produces neophobia, increases stereotypic activity, and impairs social interactions in manner analogous to that observed in ASD.

Conclusion

Increased stimulation of 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors plays a significant role in the production of lasting social and sensory deficits in adult animals exposed as neonates to SSRIs.

Keywords: Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor, Autism, Antidepressant, Serotonin, Development, Sensory Systems, Social Behavior, Neonatal Exposure, Citalopram, 8-OH-DPAT, CGS-12066B, WAY-100635, GR-127935

INTRODUCTION

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the pharmacological treatment of choice for depressed pregnant mothers and/or children with these disorders. This is largely due to their low perceived toxicity to mother, fetus and infant (Cohen et al. 2004; Wisner et al. 2000). However, studies of placental transfer of SSRIs and their metabolites in infants exposed during pregnancy have shown umbilical cord to maternal serum concentrations ratios in the range of 0.29 to 0.89 (Hendrick et al. 2003; Hostetter et al. 2000). In fact, a large fraction of infants exposed to SSRIs in utero display sign of antidepressant withdrawal in first few weeks of their life (Laine et al. 2003; Nordeng et al. 2001; Sanz et al. 2005), indicating that the fetus can be exposed to neurobiologically relevant doses of these drugs. However, despite these indications of biologically significant exposure to SSRI medication, the effects of these treatment into adult life are unknown inasmuch as no study has followed such children beyond early childhood (<72 months).

Hyperserotonemia is reported in approximately 30% of individuals diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorders (ASDs) (Cook et al. 1993; Cook 1996; Anderson et al. 1990; Veenstra Vander Weele et al. 2002). In fact, it has been suggested that abnormalities in serotonin metabolism during development may be one of the most important factors contributing to ASD. Recently, Croen et al. 2011 demonstrated an increased incidence of ASDs among children exposed early in gestation to SSRI antidepressants. This raises the disturbing possibility that developmental exposure to drugs such as SSRIs which alter serotonin metabolism may have lasting unintended neurodevelopmental consequences.

Beginning in 1981, several groups established that brief early life exposure of rats to tricyclic antidepressants such as clomipramine could result in lasting alterations in behavior. Rats exposed to these drugs from postnatal day 8 to 21 (PN8-21) displayed adult (>P90) behavioral abnormalities including deficits in male sexual behavior, sleep abnormalities, diminished shock-induced aggression, increased voluntary alcohol consumption, locomotor hyperactivity and increased immobility in the forced swim test (Hansen et al. 1997; Hilakivi et al. 1984; Maciag et al. 2006a, b; Mirmiran et al. 1981; Neil et al. 1990; Vogel et al. 1988). However, due do the lack of pharmacological specificity of the drugs being used, it was very difficult to establish a neurobiological mechanism for these behavioral abnormalities.

Our group has been able to take advantage of the highly specific SSRI antidepressants now available, such as citalopram, to more precisely probe the neurobiological mechanisms that underlie the lasting behavioral effects of early life exposure (PN8-21) to antidepressants (Maciag et al. 2006a). Using this paradigm, we have demonstrated that early life SSRI exposure results in specific disruption of sensory systems, reduced novelty-seeking behavior and disruption of both the juvenile and adult social behavioral repertoire (Rodriguez-Porcel et al. 2011). In addition, the behavioral abnormalities are accompanied by a highly reproducible constellation of neurobiological changes including reductions in the expression of key enzymes in the synthesis and reuptake of serotonin as well as abnormalities in serotonin axonal projections to forebrain structures (Maciag et al. 2006a; Weaver et al. 2010; Simpson et al. 2011; Lu et al. 2012).

Despite this progress, the possible mechanism(s) by which SSRI exposure during a critical period of development produces behavioral and neurobiological abnormalities is unclear. Serotonin is well known to play a major trophic role in brain morphogenesis, particularly in the development of sensory cortical projections. In the rat serotonergic neurons appear early in development at 12 days of gestation (reviewed in Kiyasova and Gaspar, 2011), while in humans they are evident at 5 weeks of gestation (reviewed in Kinney et al., 2011). Peak synaptogenesis ends in rats by PN21 (Aghajanian and Bloom, 1967; Jacobson 1991) and in humans by 4 years of age (Chugani 1998). Likewise, serotonin tranporter (SERT) protein is poorly expressed prenatally but undergoes a massive proliferation and subsequent ‘pruning’ in the 5–6 weeks after birth (Hansson et al. 1998; Zhou et al. 2000). Moreover, the development of the somatosensory, auditory as well as olfactory circuits is closely tied to both transient expression of SERT and serotonin uptake as well as increased expression of serotonin and its receptors in somatosensory, auditory cortex (Egaas et al. 1995; Lebrand et al, 1996,1998; Hansson et al. 1998) and olfactory bulb (McLean and Shipley 1987a,b).

Inhibiting serotonin reuptake in neonatal rats would be expected to increase synaptic concentrations of serotonin and result in increased stimulation of serotonin receptors during a critical period of development. Serotonin 1A and 1B (5-HT1A and 5-HT1B) receptors as autoreceptors and heteroreceptors have been implicated in regulation of serotonergic and nonserotonergic neuronal activity including cell firing and neurotransmitter release (Hoyer et al. 2002). We hypothesized that the long-term effects of neonatal SSRI exposure are a consequence of abnormal stimulation of 5-HT1A and/or 5-HT1B receptors as a result of increased synaptic concentrations of serotonin during brain development. The present experiments were designed to test whether selective activation of 5-HT1A and/or 5-HT1B receptors in early life results in lasting sensory and social deficits in rats comparable to those previously observed after neonatal exposure to SSRIs. To address this aim, we firstly determined whether neonatal exposure to a 5-HT1A and/or 5-HT1B receptor agonist at pharmacologically active doses can produce lasting disruptions of social and sensorimotor behaviors as are observed after neonatal treatment with SSRIs. Furthermore, if as hypothesized, early life activation of 5-HT1A or 5-HT1B receptors, by increased extracellular serotonin due to SERT inhibition is the initiating event that results in the behavioral effects of early SSRI exposure, we anticipated that co-treating rats with a SSRI and an antagonist at one of the receptor subtypes will permit the increased serotonin in the synaptic cleft to stimulate only the non-antagonized receptor. Thus, in our second experiment, we determined whether co-treatment of SSRI exposed neonatal rats with 5-HT1A or 5-HT1B antagonists, mimics the behavioral effects of SSRI and 5-HT1B or 5-HT1A receptor agonists, respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

Both male and female offspring of timed-pregnant Long Evans rats were used in these experiments. Animals were housed in a partially reversed light: dark cycle (lights on at 12:00 am, lights off at 12:00 pm) with ad libitum access to food and tap water. All procedures were approved by the UMMC Animal Care and Use Committee and complied with AAALAC and NIH standards. Pups were cross-fostered between adult females on PN2, as necessary to produce litters of 12–14 pups. On PN6-7, pups were tattooed for identification. Each litter included at least one pup in each treatment group. At PN28 pups were weaned and housed in groups of 2–3 per cage under standard laboratory conditions with unrestricted access to food and water.

For Experiment 1, rat pups were injected subcutaneously with citalopram (CTM, Toronto Research Chemicals, Toronto, Canada), (±)-8-hydroxy-dipropylaminotetralin hydrobromide (8- OH-DPAT, 5-HT1A agonist, Tocris, Ellisville, MO), 7-trifluoromethyl-4(4-methyl-1- piperazinyl)-pyrrolo[1,2-a]-quinoxaline dimaleate (CGS 12066B, 5-HT1B agonist, Tocris, Ellisville, MO) or saline in a volume of 0.1 ml twice daily (06:00 and 12:00 hours) from PN8- PN21 (total daily dose of CTM = 20 mg/kg; 8OH-DPAT = 0.50 mg/kg; CGS-12066B = 10 mg/kg). This time window corresponds roughly from late stages of gestation to first 3 years of postnatal life in humans (Maciag et al. 2006a). The rationale behind the CTM dose was based on similar blood serum levels detected in humans (Bjerkenstedt et al. 1985) and rodents (Kugelberg et al. 2001) and, similar dosages have been used in our previous rodent studies (Maciag et al. 2006a; Weaver et al. 2010; Simpson et al. 2011).The doses for agonists were chosen from extensive literature review as resulting in ED50 or greater pharmacological response in vivo in rats with 10-fold or greater selectivity for the 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors respectively (Frambes et al. 1990, Frances and Monier 1991, Gonzalez et al. 1996 and Tohyama et al. 2002). Similarly, for Experiment 2, rat pups were injected with citalopram alone or in combination with N-[2-[4-(2-Methoxyphenyl)-1-piperazinyl]ethyl]-N-2-pyridinylcyclo-hexanecarboxamide maleate (WAY-100635, 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) or N-[4-methoxy-3-(4-methyl-1-piperazinyl)phenyl]-2'-methyl-4'-(5-methyl-1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl)-1-1'- biphenyl-4-carboxamide (GR 127935, 5-HT1B receptor antagonist, Tocris, Ellisville, MO) or saline in a volume of 0.1 ml twice daily (06:00 and 12:00 hours) from P8-21 (total daily dose of CTM = 20 mg/kg; WAY-100635 = 0.6 mg/kg; GR 127935 = 6 mg/kg). The doses were based on previous literature as effective in blocking the 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors respectively (Invernizzi et al. 1996; Hjorth et al. 1997; Fletcher et al. 2002).

Behavioral Testing

Behavioral testing was conducted on rats during the dark phase of the light:dark cycle. The methodology for the conductance of the behavioral procedures has been described in detail previously (Rodriguez-Porcel et al. 2011).

Freezing response to novel tone

On PN22 rats were placed individually into locomotor activity-monitoring units (Infrared photodetector units, Opto-Varimex, Columbus Instruments) for 6 mins. After 120 sec acclimation (ambient sound level ≤ 30 dB), a tone (radio tuned to static-sound level in testing area = 70dB) was turned on for 120 sec. A final 120 sec observation without tone (ambient sound level ≤ 30 dB) was included to test recovery from tone exposure. Data was analyzed for time spent immobile during the 6 min period.

Locomotor activity

At intervals during development after weaning (PN 30, 60, and 100) rats were individually placed in to the locomotor activity-monitoring units for 20 mins. Data were analyzed for time ambulating, zone of activity, distance travelled, stereotypies, and rearing.

Juvenile play behavior

Between PN24 and PN28, pups were tested for the appearance and sequence of juvenile play behavior. Prior to testing, pups were isolated for 3.5 hrs. and later paired within gender and treatment groups with novel conspecifics of comparable weight and video recorded for 15 min. The pups were then returned to their home cage. Using a video scoring program (Noldus Observer XT Ver. 10.5), we recorded play behaviors (pinning, boxing/wrestling, following/chasing) associated with social play in peri-adolescent rats (Panksepp et al. 1984, Pellis & Pellis 1998). In addition, we also recorded the frequency/duration of time spent in stereotypic behaviors, and frequency of rearing. Stereotypic behavior was defined to be the repetitive vertical head movements exhibited by the rat pups.

Object-Conspecific preference

At PN45 and PN85, rats were tested for preference between a novel conspecific rat and a novel inanimate object. Rats to be tested were placed in the test chamber that contained a perforated Plexiglas enclosure at each end which the rat could see, touch and smell, but could not enter and video recorded for 10 min for time spent in proximity and contacts with perforated wall of the chamber containing either the conspecific rat or the inanimate object. Data was analyzed for the ratio of contact with the conspecific rat enclosure vs. contact with the novel inanimate object enclosure.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed with single factor (drug treatment) ANOVA. ANOVA for Locomotor Response to Tone included a repeated measure (tone condition) in addition to the drug treatment factor. Between-group comparisons were conducted with Fisher’s Exact test (Juvenile Play and Object-Conspecific Preference) or contrast analysis with a univariate F-test (Locomotor response to tone). Data were deemed significant when p < 0.05. The behavioral response of both genders did not differ significantly therefore were pooled for the purpose of analysis and presentation.

RESULTS

Experiment 1: Effect of neonatal exposure to SSRI (CTM), 5-HT1A (8-OH DPAT) and 5- HT1B (CGS 12066B) receptor agonists on social/sensory response behaviors

Freezing Response to a Novel Tone

Response to a novel auditory stimulus was examined using the freezing response to a novel tone. Exposure to a novel tone reduces ambulatory activity and thus elicits a rapid increase in immobility (freezing), which continues even after sound termination in all of the treatment groups examined (Fig. 1). One factor (Drug Exposure) repeated measures (Testing Condition) ANOVA revealed main effects of Testing Condition (F2,452 = 115.739, p < 0.001), Drug Exposure (F3,226 = 11.269, p < 0.001) as well as an Drug Exposure X Testing Condition interaction (F6,452 = 2.993, p = 0.007). A novel tone elicited a significantly greater increase in immobility in both the SSRI, and 5-HT1B receptor agonist exposed groups (130% and 117%, respectively) compared to controls. Moreover, the increase in immobility was exaggerated in the two groups, even after the end of tone period, reaching up to 143% and 180% higher values than the control group pretone baseline. In contrast, the magnitude of tone and post-tone response was similar across the control and 5-HT1A receptor agonist exposed groups (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect on neonatal drug exposure on locomotor activity in response to a novel tone. Data represent the mean ± SEM of SAL (saline; n = 80), CTM (citalopram, SSRI; n = 73), 8-OH-DPAT (5-HT1A receptor agonist; n = 46), and CGS 12066B (5-HT1B receptor agonist; n= 31) male and female rats. *p < 0.05 vs. SAL, +p < 0.05 vs. pretone baseline, Fisher’s least significant difference test.

Locomotor Activity

There were no significant differences in duration of ambulation, immobility, zone of activity, distance travelled, stereotypies, and rearing among the control and the neonatally exposed groups (data not shown).

Juvenile Play

There was a significant effect of drug exposure on frequencies of play behavior: Boxing/Wrestling (F3,197 = 7.191, p < 0.001), and Following/Chasing (F3,197 = 9.637, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2) although pinning behavior was unaffected by drug exposure (not shown). In contrast, the frequency of stereotypical behavior episodes (F3,197 = 7.068, p < 0.001) were markedly increased in the exposed groups compared with the control group. Parallel reductions in the duration of play behaviors (boxing/wrestling, and following/chasing), and stereotypic episodes were also observed in the exposed groups (data not shown). Of interest, a marked reduction in the exploration, as evident by lower rearing counts (F3,197 = 16.331, p < 0.001) was observed exclusively in the SSRI exposed group compared to control.

Fig. 2.

Effect on neonatal drug exposure on boxing, following/chasing, stereotypic behavior and rearing during juvenile play. Data represent the mean ±SEM of SAL (saline; n = 74), CTM (citalopram, SSRI; n = 66), 8-OH-DPAT (5-HT1A receptor agonist; n= 32), and CGS 12066B (5-HT1B receptor agonist; n= 29) male and female rats. *p < 0.05 vs. saline, Fisher’s least significant difference test.

Object Conspecific Interaction

Response to a novel conspecific animal and preference for investigating a novel animal over a novel object was tested by examining object-conspecific preference at P45. Interaction ratio (IR) was defined as the ratio of conspecific rat contact/inanimate object contact (i.e. individual contacts made with the Plexiglas wall separating the test rat from the novel object or conspecific rat). Mean comparisons revealed that saline rats interacted with conspecifics about twice as much as the drug-exposed rats (F3,186 = 21.254, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). The study was repeated at P85 in order to assess if the interaction was stable. The results were comparable with those from P45 (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Effect of neonatal drug exposure on the number of interactions with conspecific in relation with interaction with object. Data represents the mean ± SEM of the ratio of contacts with the conspecifics enclosure to that of the novel object for SAL (saline; n = 68), CTM (citalopram, SSRI; n = 56), 8-OH-DPAT (5-HT1A receptor agonist; n= 37), and CGS 12066B (5-HT1B receptor agonist; n = 29) male and female rats. *p < 0.05 compared to saline, Fisher’s least significant difference test.

Experiment 2: Effect of neonatal exposure to SSRI (CTM), SSRI and 5-HT1A (WAY 100635) or 5-HT1B (GR 127935) receptor antagonists on social/sensory response behaviors

Freezing Response to a Novel Tone

Exposure to a novel auditory stimulus reduces ambulatory activity and increases immobility (freezing), which continues to increase until after the end of tone period in all of the treatment groups examined. However, rat pups treated with SSRI alone or in combination with a 5-HT1A receptor antagonist or 5-HT1B receptor antagonist as neonates exhibited an exaggerated freezing response to a novel tone, suggesting a neophobic response to an auditory stimulus. One factor (Drug Exposure) repeated measures (Testing Condition) ANOVA revealed main effects of Testing Condition (F2,174 = 43.313, p < 0.001) as well as an Drug Exposure X Testing Condition interaction (F6,174 = 2.908, p = 0.01). Overall, novel tone elicited a significantly greater increase in immobility in the SSRI, SSRI + 5-HT1B or 5-HT1A receptor antagonist cotreated groups (117%, 139%, and 116% respectively) compared to the control group pretone baseline. However, unlike the tone interval the magnitude of post-tone response was similar across all treatment groups (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect on neonatal drug exposure on locomotor activity in response to a novel tone. Data represent the mean ± SEM of saline (SAL; n = 21), citalopram (CTM, SSRI; n = 24), CTM + GR 127935 (SSRI + 5-HT1B receptor antagonist; n = 23), and CTM + WAY 100635 (SSRI + 5-HT1A receptor antagonist; n = 23) male and female rats. *p < 0.05 vs. SAL, +p < 0.05 vs. pretone baseline, Fisher’s least significant difference test.

Locomotor Activity

No significant differences in time locomoting, distance travelled, immobility, zone of activity, stereotypies, and rearing were observed among the control and the neonatally exposed groups (data not shown).

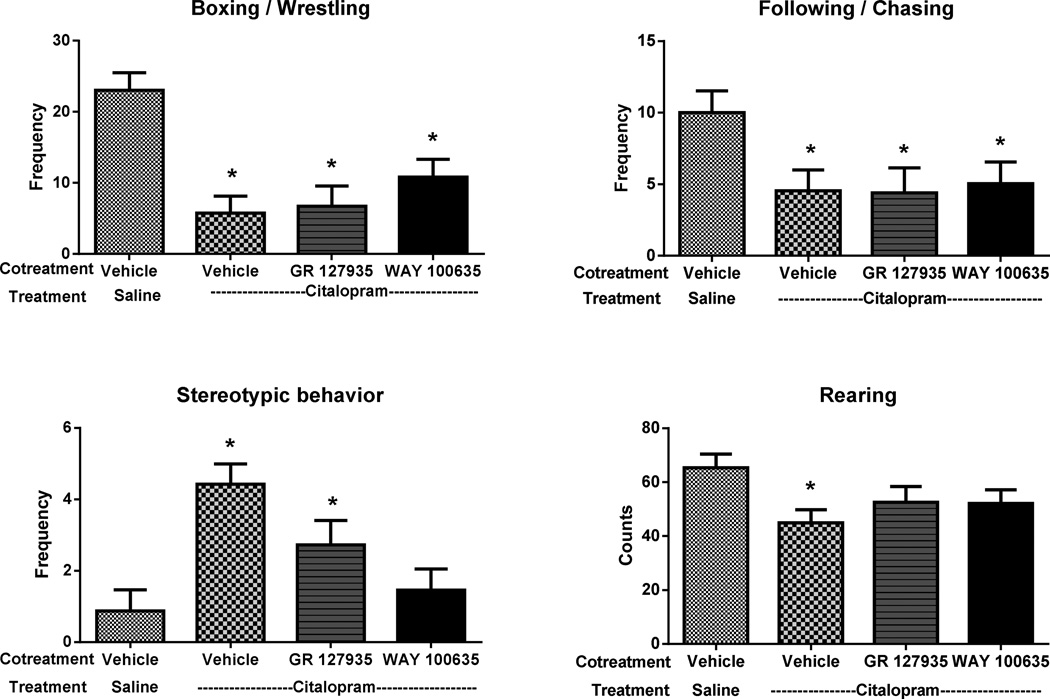

Juvenile Play Behavior

Neonatally exposed groups showed a significant reduction in the total amount (both frequency and duration) of social behaviors compared to the controls. The frequency of playing activities such as boxing/wrestling (F3,88 = 10.058, p < 0.001) and following/chasing (F3,88 = 3.075, p = 0.032) were reduced up to 75%, within the exposed groups. In contrast, rat pups treated with SSRI alone or in combination with a 5-HT1B receptor antagonist as neonates displayed an increase in the frequency of stereotypic behavior episodes (F3,88 = 7.264, p < 0.001), compared with the control group. However, neonatal treatment with SSRI and 5-HT1A receptor antagonist completely blocked the effects of SSRI on stereotypic activity suggesting that the stereotypic response resulting from early SSRI exposure requires activation of 5-HT1A receptors. Corresponding decreases in the duration of rough and tumble play behavior (boxing, and following/chasing) and increases in the duration of stereotypic behavior episodes were also observed in the exposed groups when compared to the control group (data not shown). Interestingly, social situations like juvenile play resulted in a marked decrease in the exploratory rearing behavior (F3,88 = 2.849, p =0.042) in the SSRI exposed group (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effect on neonatal drug exposure on boxing, following/chasing, stereotypic behavior and rearing during juvenile play. Data represent the mean ±SEM of saline (SAL; n = 24), citalopram (CTM, SSRI; n = 26), CTM + GR 127935 (SSRI + 5-HT1B receptor antagonist; n = 18), and CTM + WAY 100635 (SSRI + 5-HT1A receptor antagonist; n = 24) male and female rats. *p < 0.05 vs. saline, Fisher’s least significant difference test.

Object Conspecific Interaction

Mean comparisons of the IR (conspecific/inanimate object contact) revealed that the non-exposed rats interacted with the conspecifics up to twice as much as the exposed rats (F3,74 = 11.632, p < 0.001). (Fig. 6). The behavioral deficits in conspecific vs. object preference noted in young rats persisted in to adulthood (P85) (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Effect of neonatal drug exposure on the number of interactions with conspecific in relation with interaction with object. Data represents the mean ± SEM of the ratio of contacts with the conspecifics enclosure to that of the novel object for saline (SAL; n = 28), citalopram (CTM, SSRI; n= 23), CTM + GR 127935 (SSRI + 5-HT1B receptor antagonist; n = 15), and CTM + WAY 100635 (SSRI + 5-HT1A receptor antagonist; n = 12) male and female rats. *p < 0.05 compared to saline, Fisher’s least significant difference test.

DISCUSSION

In agreement with our previous study (Rodriguez-Porcel et al. 2011), the data presented here indicate that blockade of SERT by CTM during development (PN8-21), produces lasting disruptions of both social and sensorimotor behaviors in a manner analogous to ASD. Furthermore, these data support the hypothesis that increased stimulation of 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors plays a significant role in the production of lasting social and sensory deficits in adult animals exposed as neonates to SSRIs. This is initially demonstrated by the lasting sensory and social abnormalities produced by neonatal exposure (PN8-21) to 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptor agonists in rats. These initial observations were confirmed by the mimicking of these behavioral effects by co-administration of SSRI and 5-HT1B or 5-HT1A receptor antagonists respectively.

The lasting social and sensorimotor deficits induced by the SSRI citalopram is most probably the consequence of the increased extracellular serotonin levels resulting from blockade of the serotonin reuptake (Fuller 1994; Malagié et al. 1995; Fabre et al. 2000). In fact, studies with SERT knock-out mice have demonstrated that developmental inhibition of SERT significantly increases the extracellular serotonin levels in striatum and frontal cortex by 6- and 10-fold respectively (Mathews et al. 2004). Among the receptors at which excess serotonin might act to induce lasting sensory and social deficits, the 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B types appeared as the most relevant candidates due to their auto- and hetero-receptor activity and an early developmental expression profile (Hoyer et al. 2002; Azmitia 2001; Bennett-Clarke et al. 1993; Hillion et al 1994; Salichon et al. 2001). Both 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors are expressed early in embryonic life in the raphe nuclei and other serotonin terminal sites, and have been implicated in various developmental effects (Azmitia 2001; Bennett-Clarke et al. 1993; Boschert et al. 1994; Hillion et al 1994; Salichon et al. 2001). In addition, the 5-HT1B receptors are transiently expressed in all the sensory thalamic relay nuclei during early postnatal development (Bennett- Clarke et al. 1993; Laurent et al. 2002).

In terms of localization, both the 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors have double localization, existing as inhibitory autoreceptors on the serotonergic neurons (5-HT1A on the soma and dendrites of serotonin neurons in the raphe nuclei; 5-HT1B on the axon-terminals), and inhibitory postsynaptic heteroreceptors in the serotonin system's terminal fields (Pineyro and Blier 1999). Therefore, either direct or indirect activation of 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors have dual effects on serotonergic neurotransmission: activation of autoreceptors effectively inhibits 5-HT neurotransmission while, activation of postsynaptic sites, mimics the effects of 5-HT released. Thus, the overall effect of either direct or indirect activation of 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors on signal transfer in target fields represents a combination of decreased release owing to autoreceptor activation and a direct stimulation of the postsynaptic receptors.

The results of the present experiments demonstrate that rat pups, when exposed perinatally to a SSRI as well as direct or indirect stimulation of either 5-HT1A or 5-HT1B receptors display disrupted sensory processing, increased stereotypic activity, and impaired social interactions in a manner analogous to that observed in ASD. Compared with the control group, exposed groups displayed an exaggerated freezing response to a novel tone presented early in life, suggesting a neophobic response towards a novel auditory stimulus. Furthermore, in comparisons of juvenile social behavior between control- and neonatally exposed- animals, we found that exposed rats engaged in fewer social interactions with the novel rat compared with control rats. Also, a clear increase in stereotypic behaviors was evident in the exposed rats when compared to the control rats, during the juvenile play investigation. Of interest, lowered exploratory activity during the play behavior analysis was noted solely for the SSRI exposed group suggesting that this response was mediated independent of the two receptor subtypes. The data presented here also demonstrate that social interactions are affected throughout life. When given a choice between a novel object and a novel conspecific animal, neonatally exposed groups, unlike control rats, chose to investigate the novel object over the novel conspecific animal. Moreover, the behavioral deficit in conspecific vs. object preference noted in young animals persisted in to adulthood (PN85). The discrepancy in response to novel tone, for the direct (5-HT1A receptor agonist) and indirect (SSRI + 5-HT1B receptor antagonist) stimulation of 5-HT1A receptor may be due to a small difference in potency between the 5-HT1A receptor agonist and 5-HT1B receptor antagonist. Similarly, a small difference in potency between the 5-HT1B receptor agonist and 5-HT1A receptor antagonist could have resulted in the discrepancy for the stereotypic response. The effects of neonatal SSRI exposure on social and sensorimotor response behaviors are not likely related to an increase in anxiety-like behavior or exploration because there was no change in either of these behavioral indices in the elevated plus maze (Harris et al. 2011) or zero-maze (data not shown).

Our studies are in line with the developmental hyperserotonemia model of autism proposed in the Whitaker-Azmitia studies. Specifically, their group reported that exposing developing rat pups, from gestational day 12 to PN20, with a non-selective serotonin agonist, 5-methoxytryptamine, produces many of the social, behavioral, and peptide changes similar to autism (Whitaker Azmitia 2005; McNamara et al., 2008). There are many animal studies that provide a strong potential link between hyperserotonemia during early development and ASD. Both MAO-A and A/B KO mice display an array of behavioral, neuropathological abnormalities, as well as tactile and motor deficits similar to that observed in ASDs (Bortolato et al. 2013). Similarly, early exposure of rats to MAO inhibitors (both MAO-A and B), throughout development has been shown to produce increase in impulsivity, stereotypic behavior and seizures (Whitaker-Azmitia et al. 1994). Further, altered cerebellar organization and function has been reported in MAO A hypomorphic mice (Alzghoul et al. 2012). On a similar line, rats exposed prenatally to the serotonin reuptake inhibitor cocaine show less interactions in social interaction tasks as juveniles and adults and exhibit impaired ability to sustain attention (Overstreet et al. 2000; Gendle et al. 2003). However, these effects are comparatively nonspecific and may involve monoaminergic systems other than serotonin. Taken together, these findings suggest that abnormal development of the serotonin system during early development may be one of the most important factors contributing to ASD.

Interestingly, in the present study we did not detect sex differences and therefore we presented the data together. In previous studies (Weaver et al. 2010, Harris et al. 2011), the appearance of sex differences after citalopram exposure is dose-dependent. In particular, sex differences in sensitivity to citalopram seem to appear most prominently at lower drug doses. For logistic reasons, the present study used single doses of both citalopram and the 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptor selective agents. The doses were chosen to be similar to the effects of higher doses of citalopram. Further studies comparing the dose-dependency of the effect 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptor activation will be needed to determine whether direct stimulation of these receptors reveals a sex difference.

Several potential limitations must be acknowledged in this initial study. Firstly, both 5-HT1 receptor agonists are used only at single doses and additional studies will be required to determine the dose–response function for these agonists to produce neurobehavioral changes. Similarly, if as hypothesized, the initiating event for the neurobehavioral abnormalities is the early life activation of 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors, it is anticipated that simultaneous treatment with a 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptor agonist should produce similar neurobehavioral abnormalities as SSRIs. In the same vein, it is anticipated that blocking both the 5-HT1A and 5- HT1B receptors neonatally, should produce SSRI like effects due to inhibition of the negative feed-back signaling. Finally, the rich diversity of serotonin receptors creates many ways by which serotonin could affect developing cells and so the future studies can be directed towards examining the potential role of other serotonin receptor subtypes in mediating the neurobehavioral effects of early SSRI exposure. Nonetheless, these data support the hypothesis that stimulation of 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors contributes to the lasting neurobehavioral effects of early SSRI exposure. In totality, these data provide strong evidence that activation of 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors during a critical period of development, can result in lasting impairment of social and sensory response behaviors in a manner similar to that observed in ASD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Emily C. Nichols for her excellent technical assistance.

Grant Sponsers:

NIMH, NCRR; Grant numbers: MH08194, RR017701

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

None

REFERENCES

- 1.Aghajanian GK, Bloom FE. The formation of synaptic junctions in developing rat brain: a quantitative electron microscopic study. Brain Res. 1967;6(4):716–727. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(67)90128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzghoul L, Bortolato M, Delis F, Thanos PK, Darling RD, Godar SC, Zhang J, Grant S, Wang GJ, Simpson KL, Chen K, Volkow ND, Lin RC, Shih JC. Altered cerebellar organization and function in monoamine oxidase A hypomorphic mice. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63(7):1208–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. pp. 66–71. (DSM-IV) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson GM, Horne WC, Chatterjee D, Cohen DJ. The hyperserotonemia of autism. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1990;600:331–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb16893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azmitia EC. Modern view on an ancient chemical: serotonin effects on proliferation, maturation, and apoptosis. Brain Res. Bull. 2001;56:414–424. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00614-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahrick LE, Todd JT. In: Multisensory processing in autism spectrum disorders: Intersensory processing disturbance as a basis for atypical development. Stein BE, editor. The new handbook of multisensory processes Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2012. pp. 657–674. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett-Clarke CA, Leslie MJ, Chiaia NL, Rhoades RW. Serotonin 1B receptors in the developing somatosensory and visual cortices are located on thalamocortical axons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:153–157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennetto L, Kuschner ES, Hyman SL. Olfaction and taste processing in autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1015–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ben-Sasson A, Hen L, Fluss R, Cermak SA, Engel-Yeger B, Gal E. A meta-analysis of sensory modulation symptoms in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;39:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0593-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bjerkenstedt L, Flyckt L, Overo KF, Lingjaerde O. Relationship between clinical effects, serum drug concentration and serotonin uptake inhibition in depressed patients treated with citalopram. A double-blind comparison of three dose levels. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1985;28:553–557. doi: 10.1007/BF00544066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bortolato M, Godar SC, Alzghoul L, Zhang J,Darling RD, Simpson KL, Bini V, Chen K, Wellman CL, Lin RC, Shih JC. Monoamine oxidase A and A/B knockout mice display autistic-like features. Int J Neupsychopharmacology. 2013;16(4):869–888. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boschert U, Amara DA, Segu L, Hen R. The mouse 5-hydroxytryptamine 1B receptor is localized predominantly on axon terminals. Neuroscience. 1994;58:167–182. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chugani DC, Muzik O, Behen M, Rothermel R, Janisse JJ, Lee J, Chugani HT. Developmental changes in brain serotonin synthesis capacity in autistic and nonautistic children. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:287–295. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199903)45:3<287::aid-ana3>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chugani HT. A critical period of brain development: studies of cerebral glucose utilization with PET. Prev. Med. 1998;27(2):184–188. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen LS, Nonacs R, Viguera AC, Reminick A. Diagnosis and treatment of depression during pregnancy. CNS Spectr. 2004;9:209–216. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900009007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook EH, Arora RC, Anderson GM, Berry-Kravis EM, Yau S, Yeoh HC, Sklena PJ, Charak DA, Leventhal BL. Platelet serotonin studies in familial hyperserotonemia of autism. Life Sciences. 1993;52:2005–2015. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90685-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook EH. Brief report: pathophysiology of autism: neurochemistry. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1996;26:221–215. doi: 10.1007/BF02172016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Croen LA, Grether JK, Yoshida CK, Odouli R, Hendrick V. Antidepressant use during pregnancy and childhood autism spectrum disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:1104–1112. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egaas B, Courchesne E, Saitoh O. Reduced size of corpus callosum in autism. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:794–801. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540320070014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fabre V, Beaufour C, Evrard A, Rioux A, Hanoun N, Lesch KP, Murphy DL, Lanfumey L, Hamon M, Martres MP. Altered expression and functions of serotonin 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors in knock-out mice lacking the 5-HT transporter. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:2299–2310. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fletcher PJ, Azampanah A, Korth KM. Activation of 5-HT(1B) receptors in the nucleus accumbens reduces self-administration of amphetamine on a progressive ratio schedule. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:717–725. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frambes NA, Kirstein CL, Moody CA, Spear LP. 5-HT1A 5-HT1B and 5-HT2 receptor agonists induce differential behavioral responses in preweanling rat pups. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990;182:9–17. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90488-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frances H, Monier C. Tolerance to the behavioural effect of serotonergic (5-HT1B) agonists in the isolation-induced social behavioural deficit test. Neuropharmacology. 1991;30:623–627. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(91)90082-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuller RW. Minireview: Uptake inhibitors increase extracellular serotonin concentration measured by brain microdialysis. Life Sci. 1994;55:163–167. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00876-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gendle MH, Strawderman MS, Mactutus CF, Booze RM, Levitsky DA, Strupp BJ. Impaired sustained attention and altered reactivity to errors in an animal model of prenatal cocaine exposure. Dev Brain Res. 2003;147(12):85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gomot M, Belmonte MK, Bullmore ET, Bernard FA, Baron-Cohen S. Brain hyper-reactivity to auditory novel targets in children with high-functioning autism. Brain. 2008;131:2479–2488. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzalez MI, Albonetti E, Siddiqui A, Farabollini F, Wilson CA. Neonatal organizational effects of the 5-HT2 and 5-HT1A subsystems on adult behavior in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;54:195–203. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen HH, Sanchez C, Meier E. Neonatal administration of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor Lu-10-134-C increases forced swimming-induced immobility in adult rats: a putative animal model of depression? J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:1333–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansson SR, Mezey E, Hoffman BJ. Serotonin transporter messenger RNA in the developing rat brain: early expression in serotonergic neurons and transient expression in non-serotonergic neurons. Neuroscience. 1998;83:1185–1201. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00444-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris SS, Maciag D, Simpson KL, Paul IA. Dose dependent effects of neonatal SSRI exposure on adult behavior in the rat. Brain Research. 2012;1429:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hendrick V, Stowe ZN, Altshuler LL, Hwang S, Lee E, Haynes D. Placental passage of antidepressant medications. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:993–996. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hilakivi LA, Sinclair JD, Hilakivi IT. Effects of neonatal treatment with clomipramine on adult ethanol related behavior in the rat. Brain Res. 1984;317:129–132. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(84)90148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hillion J, Catelon J, Raid M, Hamon M, De Vitry F. Neuronal localization of-5-HT1A receptor mRNA and protein in rat embryonic brain stem cultures. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1994;79:195–202. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)90124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hjorth S, Westlin D, Bengtsson HJ. WAY100635-induced augmentation of the 5-HT-elevating action of citalopram: Relative importance of the dose of the 5-HT1A (auto) receptor blocker versus that of the 5-HT reuptake inhibitor. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:461–465. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hostetter A, Ritchie JC, Stowe ZN. Amniotic fluid and umbilical cord blood concentrations of antidepressants in three women. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:1032–1034. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00958-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoyer D, Hannon JP, Martin GR. Molecular, pharmacological and functional diversity of 5-HT receptors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:533–554. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00746-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Invernizzi R, Bramante M, Samanin R. Role of 5-HT1A receptors in the effects of acute and chronic fluoxetine on extracellular serotonin in the frontal cortex. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;54:143–147. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobson M. Developmental Neurobiology. New York: Plenum Press; 1991. Formation of dendrites and development of synaptic connections; pp. 223–284. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kern JK, Trivedi MH, Grannemann BD, Garver CR, Johnson DG, Andrews AA, Savla JS, Mehta JA, Schroeder JL. Sensory correlations in autism. Autism. 2007;11:123–134. doi: 10.1177/1362361307075702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kinney HC, Broadbelt KG, Haynes RL, Rognum IJ, Paterson DS. The serotonergic anatomy of the developing human medulla oblongata: Implications for pediatric disorders of homeostasis. J. Chem. Anatomy. 2011;41:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kiyasova V, Gaspar P. Development of raphe serotonin neurons from specification to guidance. Eur. J. Neuroscience. 2011;34:1553–1562. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07910.x. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kugelberg FC, Apelqvist G, Carlsson B, Ahlner J, Bengtsson F. In vivo steady-state pharmacokinetic outcome following clinical and toxic doses of racemic citalopram to rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;132:1683–1690. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laine K, Heikkinen T, Ekblad U, Kero P. Effects of exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy on serotonergic symptoms in newborns and cord blood monoamine and prolactin concentrations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:720–726. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laurent A, Goaillard JM, Cases O, Lebrand C, Gaspar P, Ropert N. Activity-dependent presynaptic effect of serotonin 1B receptors on the somatosensory thalamocortical transmission in neonatal mice. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:886–900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00886.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lebrand C, Cases O, Adelbrecht C, Doye A, Alvarez C, El Mestikawy S, Seif I, Gaspar P. Transient uptake and storage of serotonin in developing thalamic neurons. Neuron. 1996;17:823–835. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lebrand C, Cases O, Wehrle R, Blakely RD, Edwards RH, Gaspar P. Transient developmental expression of monoamine transporters in the rodent forebrain. J Comp Neurol. 1998;401:506–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu Y, Simpson KL, Weaver KJ, Lin RC. Differential distribution patterns from medial prefrontal cortex and dorsal raphe to the locus coeruleus in rats. Anat Record. 2012;295(7):1192–1201. doi: 10.1002/ar.22505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maciag D, Simpson KL, Coppinger D, Lu Y, Wang Y, Lin RC, Paul IA. Neonatal antidepressant exposure has lasting effects on behavior and serotonin circuitry. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006a;31:47–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maciag D, Williams L, Coppinger D, Paul IA. Neonatal Citalopram Exposure Produces Lasting Changes in Behavior which are Reversed by Adult Imipramine Treatment. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2006b;532:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malagié I, Trillat AC, Jacquot C, Gardier AM. Effects of acute fluoxetine on extracellular serotonin levels in the raphe: an in vivo microdialysis study. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;286:213–217. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00573-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mathews TA, Fedele DE, Coppelli FM, Avila AM, Murphy DL, Andrews AM. Gene dose-dependent alterations in extraneuronal serotonin but not dopamine in mice with reduced serotonin transporter expression. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2004;140:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McBride PA, Anderson GM, Hertzig ME, Snow ME, Thompson SM, Khait VD, Shapiro T, Cohen DJ. Effects of diagnosis, race, and puberty on platelet serotonin levels in autism and mental retardation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:767–776. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199807000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McLean JH, Shipley MT. Serotonergic afferents to the rat olfactory bulb: I. Origins and laminar specificity of serotonergic inputs in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 1987a;7:3016–3028. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-10-03016.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McLean JH, Shipley MT. Serotonergic afferents to the rat olfactory bulb: II. Changes in fiber distribution during development. J Neurosci. 1987b;7:3029–3039. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-10-03029.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McNamara IM, Borella AW, Bialowas LA, Whitaker-Azmitia PM. Further studies in the developmental hyperserotonemia model (DHS) of autism: Social, behavioral and peptide changes. Brain Research. 2008;1189:203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mirmiran M, van de Poll NE, Corner MA, van Oyen HG, Bour HL. Suppression of active sleep by chronic treatment with chlorimipramine during early postnatal development: effects upon adult sleep and behavior in the rat. Brain Res. 1981;204:129–146. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90657-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neill D, Vogel G, Hagler M, Kors D, Hennessey A. Diminished sexual activity in a new animal model of endogenous depression. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 1990;14:73–76. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nordeng H, Lindemann R, Perminov KV, Reikvam A. Neonatal withdrawal syndrome after in utero exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Acta Paediatr. 2001;90:288–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Overstreet DH, Moy SS, Lubin DA, Lieberman JA, Johns JM. Enduring effects of prenatal cocaine administration on emotional behavior in rats. Physiol Behav. 2000;70(12):149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00245-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Panksepp J, Siviy S, Normansell L. The Psychobiology of Play: Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 1984;8:465–492. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(84)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pellis MS, Pellis VC. Play fighting of rats in comparative perspective: a scheme for neurobehavioral analyses. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 1998;23:87–101. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(97)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pineyro G, Blier P. Autoregulation of serotonin neurons: role in antidepressant drug action. Pharmacol. Rev. 1999;51:533–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rodriguez-Porcel F, Green DL, Khatri N, Swilley S, Lin RCS, Paul IA. Neonatal exposure of rats to antidepressants affects behavioral reactions to novelty and social interactions in a manner analogous to autistic spectrum disorders. Anat Rec. 2011;294:1726–1735. doi: 10.1002/ar.21402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salichon N, Gaspar P, Upton AL, Picaud S, Hanoun N, Hamon M, et al. Excessive activation of serotonin (5-HT) 1B receptors disrupte the formation of sensory maps in monoamine oxidase and 5-HT transporter knock-out mice. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:884–896. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-00884.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sanz EJ, De-las-Cuevas C, Kiuru A, Bate A, Edwards R. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnant women and neonatal withdrawal syndrome: a database analysis. Lancet. 2005;365:482–487. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17865-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simpson KL, Weaver KJ, de Villers-Sidani E, Lu JY, Cai Z, Pang Y, Rodriguez-Porcel F, Paul IA, Merzenich M, Lin RC. Perinatal antidepressant exposure alters cortical network function in rodents. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18465–18470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109353108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Singh VK, Singh EA, Warren RP. Hyperserotonemia and serotonin receptor antibodies in children with autism but not mental retardation. Biol. Psychiatry. 1997;41:753–755. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00522-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tohyama Y, Yamane F, Fikre Merid M, Blier P, Diksic M. Effects of serotine receptors agonists, TFMPP and CGS12066B, on regional serotonin synthesis in the rat brain: an autoradiographic study. J Neurochem. 2002;80:788–798. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Kim SJ, Lord C, Courchesne R, Akshoomoff N, Leventhal BL, Courchesne E, Cook EH. Transmission disequilibrium studies of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor gene (HTR2A) in autism. Am J Med Genet. 2002;114:277–283. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vogel G, Hartley P, Neill D, Hagler M, Kors D. Animal depression model by neonatal clomipramine: reduction of shock induced aggression. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1988;31:103–106. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90319-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weaver KJ, Paul IA, Lin RCS, Simpson KL. Neonatal exposure to citalopram selectively alters the expression of the serotonin transporter in the hippocampus: Dose-dependent effects. Anat Record. 2010;293:1920–1932. doi: 10.1002/ar.21245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Whitaker-Azmitia PM, Zhang X, Clarke C. Effects of gestational exposure to monoamine oxidase inhibitors in rats: preliminary behavioral and neurochemical studies. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1994;11(2):125–132. doi: 10.1038/npp.1994.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Whitaker-Azmitia PM. Behavioral and cellular consequences of increasing serotonergic activity during brain development: a role in autism? Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wisner KL, Zarin DA, Holmboe ES, Appelbaum PS, Gelenberg AJ, Leonard HL, et al. Risk-benefit decision making for treatment of depression during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1933–1940. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou FC, Sari Y, Zhang JK. Expression of serotonin transporter protein in developing rat brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2000;119:33–45. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]