Abstract

Two glutamate receptors, metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) and ionotropic NMDA receptors (NMDAR), functionally interact with each other to regulate excitatory synaptic transmission in the mammalian brain. In exploring molecular mechanisms underlying their interactions, we found that Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIα (CaMKIIα) may play a central role. The synapse-enriched CaMKIIα directly binds to the proximal region of intracellular C terminal tails of mGluR5 in vitro. This binding is state-dependent: inactive CaMKIIα binds to mGluR5 at a high level whereas the active form of the kinase (following Ca2+/calmodulin binding and activation) loses its affinity for the receptor. Ca2+ also promotes calmodulin to bind to mGluR5 at a region overlapping with the CaMKIIα-binding site, resulting in a competitive inhibition of CaMKIIα binding to mGluR5. In rat striatal neurons, inactive CaMKIIα constitutively binds to mGluR5. Activation of mGluR5 Ca2+-dependently dissociates CaMKIIα from the receptor and simultaneously promotes CaMKIIα to bind to the adjacent NMDAR GluN2B subunit, which enables CaMKIIα to phosphorylate GluN2B at a CaMKIIα-sensitive site. Together, the long intracellular C-terminal tail of mGluR5 seems to serve as a scaffolding domain to recruit and store CaMKIIα within synapses. The mGluR5-dependent Ca2+ transients differentially regulate CaMKIIα interactions with mGluR5 and GluN2B in striatal neurons, which may contribute to crosstalk between the two receptors.

Keywords: striatum, nucleus accumbens, calcium, calmodulin, glutamate, mGluR, GluN2B, NR2B, G protein-coupled receptor

INTRODUCTION

Glutamate is a prominent transmitter in the mammalian brain. Through activating ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR), glutamate controls neural communication (Niswende and Conn, 2010; Traynelis et al., 2010). The mGluRs are a group of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR). Eight mGluR subtypes (mGluR1-8) are classified into three functional groups. Group I mGluRs (mGluR1 and mGluR5) are particularly noticeable due to their connections to a distinct signaling pathway (Niswende and Conn, 2010). Upon activation, Gα q-coupled mGluR1/5 stimulate phospholipase Cβ1 (PLC) to hydrolyze phosphoinositide into inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate and diacylglycerol. The former releases Ca2+ from internal stores. Released Ca2+ in turn modulates multiple downstream targets. Group I mGluRs are broadly expressed in the brain and are typically distributed postsynaptically as distinguished from other groups of mGluRs (Niswende and Conn, 2010). In the striatum, mGluR5 is mostly enriched and is abundant in medium spiny projection neurons in this region (Testa et al., 1994; Tallaksen-Greene et al., 1998). As a GPCR, mGluR5 is characterized by a remarkably large intracellular C terminus (CT, 345 amino acids). This provides mGluR5 with high accessibility to various cytosolic binding partners, although only a few of them have been identified so far (Enz, 2007; 2012; Fagni, 2012).

The N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) is a major member of ionotropic glutamate receptors. The receptor is assembled into a functional ion channel with the obligatory GluN1 and the modulatory GluN2 subunits (Traynelis et al., 2010). GluN2B (formerly known as NR2B) is a prime modulatory subunit of NMDARs in the forebrain. Like mGluR5, GluN2B possesses a uniquely long CT (644 amino acids) accessible for robust protein-protein interactions. In fact, a panel of submembranous proteins has been found to interact with GluN2B CT (Bard and Groc, 2011). Central among them is Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), a serine/threonine kinase enriched at synaptic sites (Kelly et al., 1984). This kinase, after being activated by Ca2+ and calmodulin (CaM), is recruited to the GluN2B CT domain to phosphorylate a serine residue (S1303) and regulate the NMDA receptor function (Omkumar et al., 1996; Strack and Colbran, 1998; Leonard et al., 1999).

NMDARs are present at both synaptic and extrasynaptic locations. GluN1/GluN2B heteromers are a principal extrasynaptic NMDAR subtype (Petralia, 2012). Since mGluR5 is also typically distributed at perisynaptic and extrasynaptic locations (Lujan et al., 1996; Kuwajima et al., 2004), mGluR5 may readily crosstalk with adjacent GluN2B-containing NMDARs. Indeed, mGluR5 consistently potentiated NMDARs in many types of cells (Huang and van den Pol 2007; Rosenbrock et al., 2010). This positive mGluR5-NMDAR coupling is essential for normal synaptic transmission, although how mGluR5 potentiates NMDARs is poorly understood.

In this study, we investigated the interaction of CaMKII with mGluR5 and GluN2B. We found that CaMKIIα binds to the proximal CT region of mGluR5. The binding is Ca2+-sensitive. Through activating CaMKIIα and CaM, Ca2+ dissociates CaMKIIα from mGluR5 in vitro and in striatal neurons. On the other hand, activated CaMKIIα by the mGluR5 agonist binds to GluN2B, which enable CaMKIIα to phosphorylate GluN2B at a CaMKIIα-sensitive site (S1303). These data unravel an mGluR5- and Ca2+-regulated CaMKIIα interaction with GluN2B which may link mGluR5 to NMDARs.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male Wistar rats weighting 225–350 g (Charles River, New York, NY) were used. Animals were individually housed at 23°C and humidity of 50 ± 10% with food and water available ad libitum. The animal room was on a 12/12 h light/dark cycle with lights on at 0700. All animal use procedures were in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments) guidelines have been followed.

Cloning and expression of glutathione S-transferase (GST)-fusion proteins

GST-fusion proteins were synthesized as described previously (Liu et al., 2009; Guo et al., 2010). Briefly, the cDNA fragments encoding the different intracellular loops (IL) and CT fragments, including mGluR5-IL1 (I602-E615), mGluR5-IL2 (R667-Q692), mGluR5-IL3 (K759-K771), mGluR5-CT1 (K827-L964), mGluR5-CT2 (Y965-L1171), mGluR5-CT1a (H845-L875), mGluR5-CT1b (L875-K917) or mGluR5-CT1c (K917-L964), were generated by polymerase chain reaction amplification from full-length mGluR5a cDNA clones. The fragments were subcloned into BamHI-EcoRI sites of the pGEX4T-3 plasmid (Amersham Biosciences, Arlington Heights, IL). Initiation methionine residues and stop codons were incorporated where appropriate. To confirm appropriate splice fusion, all constructs were sequenced. GST-fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 cells (Amersham) and purified from bacterial lysates as described by the manufacturer. His-tagged CaMKIIα-FL (M1-H478) was expressed and purified via a baculovirus/Sf9 insect cell expression system.

Western blot analysis

Western blots were performed as described previously (Guo et al., 2010; Jin et al., 2013). Briefly, proteins were separated on SDS NuPAGE Bis-Tris 4–12% gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). They were then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4° C. This was followed by an incubation of secondary antibodies (1:2,000). Immunoblots were developed with the enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ).

In vitro binding assay

His-tagged CaMKIIα (~ 57 kDa) was equilibrated to binding buffer containing 200 mM NaCl, 0.2% Triton X-100, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, and 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5). CaCl2 (0.5 mM), CaM (1 μM), or EGTA (1 mM) was added as indicated. Binding reactions were initiated by adding purified GST-fusion proteins and were remained at 4°C for 2–3 h. GST-fusion proteins were precipitated using 100 μl of 10% glutathione Sepharose. The precipitate was washed three times with binding buffer. Bound proteins were eluted with 2 × lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS) loading buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with a specific antibody.

Affinity purification (pull-down) assay

Rats were anesthetized and decapitated. Rat brains were removed and the striatum was dissected. Striatal tissue was homogenized in RIPA buffer. Solubilized striatal extracts (50–100 μg of protein) were diluted with 1 × PBS/1% Triton X-100 and incubated with 50% (v/v) slurry of glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham) saturated with GST alone or with a GST-fusion protein (5–10 μg) at 4°C for 2–3 h. Beads were washed four times with 1 × PBS/1% Triton X-100. Bound proteins were eluted with 2 × LDS sample buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with a specific antibody.

Coimmunoprecipitation

This was performed by following a previously published procedure (Jin et al., 2013). Briefly, rat brains were removed after anesthesia and coronal sections were cut. The striatum was removed and homogenized on ice in the homogenization buffer containing 0.32 M sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, a protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific), and a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Homogenates were centrifuged (760 g, 10 min) at 4° C. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged (10,000 g, 30 min) to obtain P2 pellets (synaptosomal fraction), which were then solubilized in the homogenization buffer containing 1% sodium deoxycholate (1 h). Solubilized proteins (150 μg) were incubated with a rabbit antibody against CaMKIIα or mGluR5. The complex was precipitated with 50% protein A or G agarose/sepharose bead slurry (Amersham). Proteins were separated and detected in immunoblots with a mouse antibody against CaMKIIα or mGluR5.

Autophosphorylation of CaMKIIα

Autophosphorylation of CaMKIIα were achieved by incubating 500 ng CaMKIIα in 25 μl reaction buffer containing 50 mM PIPES, pH 7.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 50 μM ATP, and 1 μM CaM for 10 min at 30° C. The reaction was stopped by adding EGTA (5 mM final concentration) on ice. Aliquots (5 μl) of the autophosphorylated kinases were immediately used in in vitro binding assays.

Striatal slice preparation

Striatal slices were prepared as described previously (Liu et al., 2009; Jin et al., 2013).

Antibodies and pharmacological agents

Antibodies used in this study include a rabbit antibody against mGluR5 (Millipore; 1:1,000), CaMKIIα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1,000), phospho-CaMKIIα-T286 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA; 1:1,000), GluN2B (Millipore; 1:1,000), phospho-GluN2B-S1303 (Millipore; 1:1,000), or GST (Sigma; 1:1,000), a mouse antibody against mGluR5 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA; 1:1,000), CaMKIIα (Santa Cruz; 1:1,000), or GluN2B (Millipore; 1:1,000), or a goat antibody against CaMKIV (Santa Cruz; 1:1,000). Pharmacological agents, including (RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) and 3-((2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-4-yl)ethynyl)pyridine hydrochloride (MTEP) were purchased from Tocris Cookson Inc. (Ballwin, MO). Ionomycin, KN93, and KN92 were purchased from Sigma. L290-A309 peptides were purchased from Abbiotec (San Diego, CA). All drugs were freshly prepared at the day of experiments.

Statistics

The results are presented as means ± SEM. The data were evaluated using Student’s t-test or a one- or two-way analysis of variance, as appropriate, followed by a Bonferroni (Dunn) comparison of groups using least-squares-adjusted means. Probability levels of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

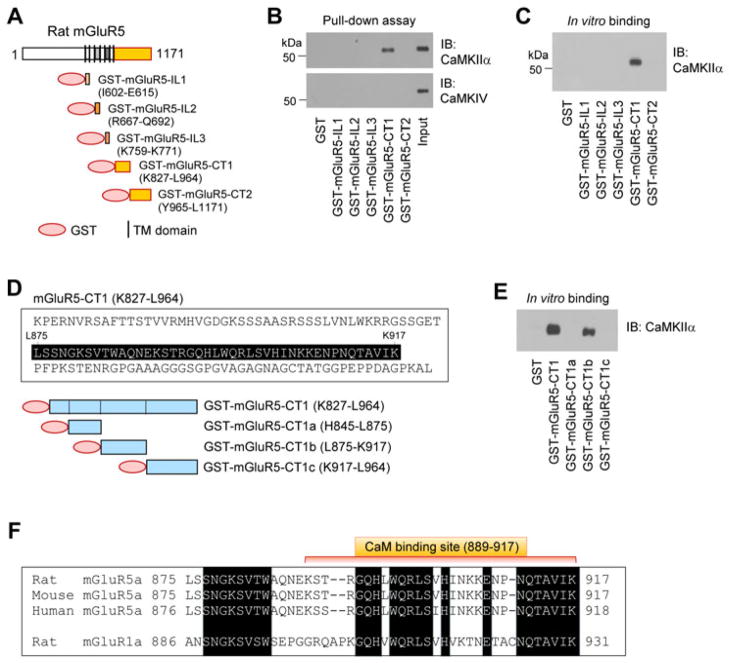

CaMKIIα binds to mGluR5

Both CaMKII and mGluR5 are enriched at synaptic sites. We thus first explored whether CaMKII interacts with mGluR5. To this end, we synthesized a panel of GST-fusion proteins containing different intracellular domains of mGluR5, including the IL1, IL2, IL3, CT1, and CT2 (Fig. 1A). Using these immobilized baits in pull-down assays with soluble rat striatal lysates, we investigated the possible interaction between CaMKIIα and mGluR5. The membrane proximal fragment of mGluR5-CT, i.e., GST-mGluR5-CT1 (K827-L964), pulled down CaMKIIα (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the distal fragment of mGluR5-CT, GST-mGluR5-CT2 (Y965-L1171), did not. Neither did GST alone and other GST-fusion proteins containing IL1, IL2, or IL3. All GST-fusion proteins did not precipitate CaMKIV (Fig. 1B). Thus, CaMKIIα interacts with mGluR5. To determine whether CaMKIIα directly binds to mGluR5, we assayed the binding activity of purified CaMKIIα and mGluR5 in vitro. GST-mGluR5-CT1, but not other GST-fusion proteins or GST alone, precipitated CaMKIIα (Fig. 1C), supporting the direct binding of the two proteins. All blots were probed in parallel with a GST antibody to ensure equivalent protein loading (data not shown).

Figure 1. Interactions between CaMKIIα and mGluR5.

A, GST-fusion proteins containing individual intracellular domains of rat mGluR5. B, Interactions of CaMKIIα with mGluR5. Interactions were detected in pull-down assays with immobilized GST-fusion proteins and rat striatal lysates. Note that mGluR5-CT1 selectively pulled down CaMKIIα since mGluR5-CT1 did not precipitate CaMKIV. C, Binding of CaMKIIα to mGluR5. Binding activities between GST or GST-fusion proteins and purified recombinant CaMKIIα were detected in in vitro binding assays. D, GST-fusion proteins containing different mGluR5-CT1 fragments. E, Binding of CaMKIIα to mGluR5-CT1 fragments as detected in in vitro binding assays with GST-fusion mGluR5-CT1 fragments and purified CaMKIIα. Note that CT1b, but not CT1a and CT1c, bound to CaMKIIα. F, CT1b sequences of mGluR5 from the rat, mouse, and human aligned with the corresponding CT region of rat mGluR1a. Amino acids were aligned using clustal W. Dark boxes indicate the regions of homology. A CaM binding site on rodent mGluR5 (K889-K917) is indicated. Pull-down and in vitro binding assays were conducted in the presence of EGTA (1 mM). Proteins bound to GST-fusion proteins in either pull-down or binding assays were visualized with immunoblots (IB) using the specific antibodies as indicated. The experiments were repeated independently for three times.

To identify an accurate CaMKIIα binding site on mGluR5-CT1, we evaluated binding affinity of truncated CT1 fragments, CT1a-c (Fig. 1D), for CaMKIIα. GST-CT1b (L875-K917) precipitated CaMKIIα, while GST-CT1a (H845-L875) and GST-CT1c (K917-L964) did not (Fig. 1E). Thus, CT1b (43 amino acids) is a critical site for CaMKIIα binding. Noticeably, this site is highly conserved among mammals and overlaps with a dominant CaM binding motif on mGluR5-CT (Fig. 1F) (Minakami et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2011). However, a same region from mGluR1a-CT lacks the interaction with either CaM (Choi et al., 2011) or CaMKIIα (Jin et al., 2013), despite a relatively high sequence homology in this region between mGluR5 and mGluR1a (Fig. 1F).

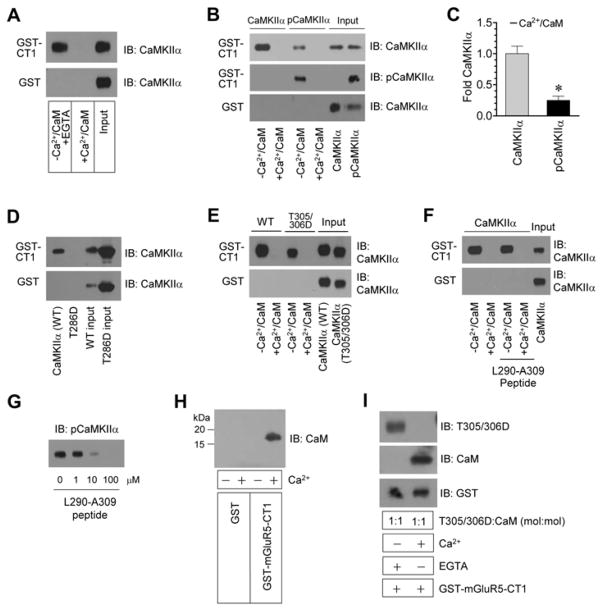

Ca2+/CaM regulate CaMKIIα binding to mGluR5

CaM, as a Ca2+-binding protein, is quickly bound by Ca2+ when there is a Ca2+ rise. Ca2+-bound CaM then interacts with and regulates various downstream targets, including CaMKII. To assess the impact of Ca2+/CaM on CaMKIIα-mGluR5 binding, we monitored the binding of the two proteins in the absence and presence of Ca2+/CaM. Without Ca2+/CaM (but with 1 mM EGTA, a Ca2+ chelator), CaMKIIα bound to mGluR5-CT1 (Fig. 2A), similar to the results observed above. Surprisingly, in the presence of Ca2+ (0.5 mM)/CaM (1 μM), CaMKIIα did not show detectable binding (Fig. 2A). This indicates that Ca2+/CaM inhibit the binding of CaMKIIα to mGluR5. We next analyzed mechanisms underlying this inhibition. Ca2+-bound CaM binds to CaMKIIα, leading to activation of the kinase. This activation may alter the binding affinity of CaMKII for mGluR5. Indeed, T286-autophosphorylated CaMKIIα, an active form of the kinase, exhibited a substantially lower level of binding to mGluR5-CT1 as compared to unphosphorylated CaMKIIα (Fig. 2B and 2C). Similarly, the T286D CaMKIIα mutant, a constitutively active CaMKIIα that shares the property of autophosphorylated CaMKIIα, lacked the binding to mGluR5-CT1 (Fig. 2D). In contrast, a Ca2+/CaM binding-defective and activation-incompetent CaMKIIα mutant, T305/306D (Colbran and Soderling, 1990), displayed the binding comparable to wild-type (WT) CaMKIIα (Fig. 2E). These results support a notion that inactive CaMKIIα is sufficient to bind to mGluR5, while active CaMKIIα has little or no affinity for the receptor.

Figure 2. Ca2+/CaM-mediated regulation of CaMKIIα binding to mGluR5.

A, CaMKIIα binding to mGluR5-CT1 as detected in in vitro binding assays in the presence or absence of Ca2+/CaM. Either CaCl2 (0.5 mM)/CaM (1 μM) or EGTA (1 mM) without CaCl2/CaM were added into binding solutions. B, T286-autophosphorylation reduced the binding of CaMKIIα to mGluR5-CT1. CaMKIIα was autophosphorylated prior to binding assays. The T286-autophosphorylated state of CaMKIIα was validated by immunoblots with a T286 phospho-specific antibody. C, A graph of the data from (B). D, CaMKIIα wild-type (WT) but not the T286D phosphomimetic mutant bound to mGluR5-CT1. Binding assays were performed in the absence of Ca2+/CaM. E, Binding of WT and T305/306D mutant CaMKIIα to mGluR5-CT1 in the absence or presence of Ca2+/CaM. F, Effects of the inhibitory peptide (L290-A309) on the CaMKIIα-mGluR5 binding. G, Effects of the L290-A309 peptide on T286 autophosphorylation of CaMKIIα. H, CaM bound to mGluR5-CT1 in the presence but not absence of Ca2+. I, Binding of the T305/306 mutant and CaM to mGluR5-CT1 in the absence or presence of Ca2+. Binding assays were performed between CaMKIIα, pCaMKIIα, CaMKIIα mutants, or CaM and immobilized GST or GST-mGluR5-CT1 in the absence or presence of CaCl2 (0.5 mM), CaM (1 μM), or L290-A309 (100 μM) (F) as indicated. EGTA (1 mM) was added in the assays lacking CaCl2. Bound CaMKIIα, pCaMKIIα, CaMKII mutant, or CaM proteins were visualized by immunoblots (IB). Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3 per group). *p < 0.05 versus CaMKIIα.

In addition to binding to CaMKII, Ca2+-activated CaM binds to mGluR5. Given the fact that CaM binds to a site overlapping with the CaMKIIα binding region on mGluR5 (Fig. 1F) (Minakami et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2011), CaM may compete with CaMKIIα for the mGluR5 binding via a Ca2+-dependent manner. In Fig. 2E, we noticed that even the inactive form of CaMKIIα (i.e., T305/306D) did not bind to mGluR5-CT1 if Ca2+/CaM were present, indicating the likelihood that CaM inhibits CaMKII interactions with mGluR5. Consistent with this, the L290-A309 peptide that contains the core CaM-binding domain on CaMKIIα and thereby competitively blocks CaM activation of CaMKIIα (Colbran and Soderling, 1990) did not resume the binding of CaMKIIα in the presence of CaM (Fig. 2F). The efficacy of the peptide in blocking CaMKIIα activation was confirmed by the finding that the peptide concentration-dependently blocked T286 autophosphorylation of the kinase (Fig. 2G). CaM in fact directly bound to mGluR5-CT1 in a Ca2+-sensitive fashion (Fig. 2H). In reactions containing both T305/306D mutants and CaM at equal molar concentrations, the binding of T305/306D mutants and CaM to mGluR5-CT1 occurred in the absence and presence of Ca2+, respectively (Fig. 2I). Thus, Ca2+ not only activates CaMKIIα to release it from mGluR5, but also activates CaM to sequentially occupy the same site on mGluR5.

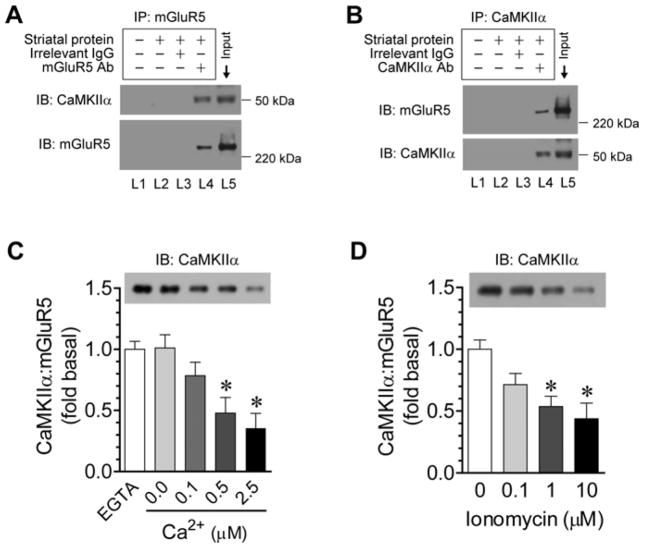

CaMKIIα interacts with mGluR5 in striatal neurons in vivo

To determine whether native CaMKIIα and mGluR5 interact with each other in striatal neurons in which mGluR5 is particularly prominent (Testa et al., 1994; 1995; Kerner et al., 1997), we performed coimmunoprecipitation with solubilized synaptosomal fractions from the adult rat striatum. CaMKIIα co-precipitated with mGluR5 dimers (a functional form of mGluR5 in vivo) (Fig. 3A). In reverse coimmunoprecipitation, mGluR5 was visualized in CaMKIIα precipitates (Fig. 3B). Thus, endogenous CaMKIIα is constitutively associated with mGluR5 in striatal neurons under normal conditions.

Figure 3. Interactions of endogenous CaMKIIα with mGluR5 in rat striatal neurons.

A and B, Representative immunoblots showing CaMKIIα and mGluR5 interactions in striatal neurons as detected by coimmunoprecipitation (IP). No precipitating antibody, an irrelevant IgG or an mGluR5 antibody was used in lane 2 (L2), 3 (L3) or 4 (L4), respectively. No striatal proteins and antibodies were used in lane 1 (L1). C, Effects of Ca2+ on the association of CaMKIIα with mGluR5 in rat striatal lyses. D, Effects of ionomycin (10 min) on the association of CaMKIIα with mGluR5 in striatal slices. Note that CaMKIIα-mGluR5 interactions were concentration-dependently reduced after adding Ca2+ or ionomycin to striatal lyses or slices, respectively. Coimmunoprecipitation was performed with solubilized striatal synaptosomal proteins to detect interactions between CaMKIIα and mGluR5. Precipitated proteins were visualized by immunoblots (IB) with indicated antibodies. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3 per group). *p < 0.05 versus EGTA or vehicle.

To explore whether Ca2+ regulates CaMKIIα-mGluR5 interactions, we examined their interactions in response to Ca2+ stimulation. In rat striatal lysates, adding Ca2+ (0.1–2.5 μM) concentration-dependently reduced the coimmunoprecipitation of CaMKIIα and mGluR5 (Fig. 3C). Similarly, in striatal neurons, CaMKIIα and mGluR5 displayed a downregulated interaction after cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels were elevated. This was shown in rat striatal slices, in which a Ca2+ ionophore, ionomycin (0.1–10 μM, 10 min), lowered the coimmunoprecipitation of the two proteins (Fig. 3D). These data demonstrate a Ca2+-dependent dissociation of preformed CaMKIIα from mGluR5.

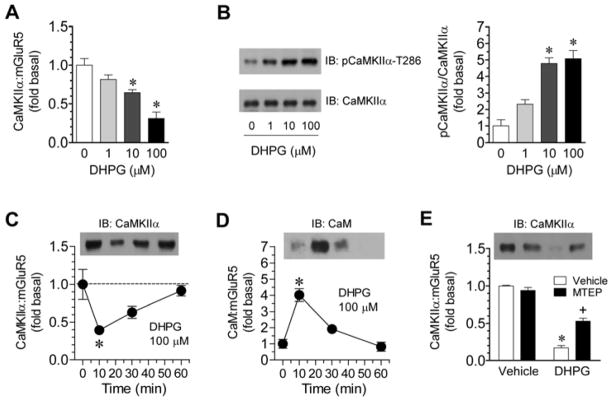

To identify a physiological Ca2+ source capable of regulating the interaction, we evaluated the role of mGluR5. mGluR5 is well known to trigger intracellular Ca2+ release (Niswende and Conn, 2010). In rat striatal slices, adding an mGluR1/5-selective agonist DHPG (1–100 μM, 10 min) concentration-dependently reduced the formation of CaMKIIα-mGluR5 complexes (Fig. 4A). In parallel, pCaMKIIα was concentration-dependently elevated by DHPG (Fig. 4B). The DHPG effect was rapid and transient as the reduction of CaMKIIα-mGluR5 associations reached a peak at 10 min and was fully recovered at 60 min (Fig. 4C). In contrast to the release of CaMKIIα from mGluR5, CaM increased its associations with mGluR5. As shown in Fig. 4D, a rapid and reversible rise in the coimmunoprecipitation of CaM and mGluR5 was observed following DHPG treatment. These results reveal an mGluR5-mediated Ca2+ source which contributes to removing CaMKIIα previously bound to mGluR5. Consistent with this notion, pretreatment with the mGluR5 selective antagonist MTEP (10 μM, 30 min prior to DHPG) significantly reversed the reduction of CaMKIIα-mGluR5 associations (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4. Effects of DHPG on interactions between CaMKIIα and mGluR5 in rat striatal neurons.

A and B, Concentration-dependent effects of DHPG (10 min) on CaMKIIα-mGluR5 interactions (A) and T286 phosphorylation of CaMKIIα (pCaMKIIα-T286) (B) in striatal slices. Note that CaMKIIα-mGluR5 interactions were reduced, whereas T286 phosphorylation of CaMKIIα was elevated, by DHPG in a concentration-dependent manner. C and D, Time-dependent effects of DHPG on CaMKIIα-mGluR5 (C) and CaM-mGluR5 (D) interactions in striatal slices. DHPG was incubated in slices at 100 μM for different durations (10, 30, or 60 min) prior to sample collections. Note that DHPG time-dependently reduced and enhanced CaMKIIα-mGluR5 and CaM-mGluR5 interactions, respectively. E, Effects of the mGluR5 antagonist MTEP on the DHPG-induced reduction in CaMKIIα-mGluR5 interactions in striatal slices. MTEP (10 μM) was applied 30 min prior to and during DHPG incubation (100 μM, 10 min). Coimmunoprecipitation with solubilized striatal synaptosomal proteins was performed to detect interactions between CaMKIIα and mGluR5 (A, C, and E) or between CaM and mGluR5 (D). Precipitated proteins were visualized by immunoblots (IB) with indicated antibodies. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3–6 per group). *p < 0.05 versus vehicle. +p < 0.05 versus vehicle + DHPG.

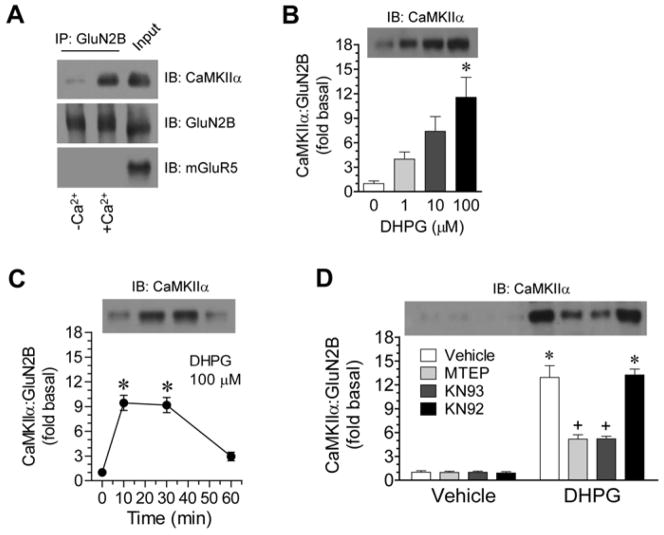

mGluR5 recruits CaMKIIα to GluN2B

We next explored the possible destination of the dissociated CaMKIIα. CaMKIIα after dissociated from mGluR5 may migrate to an adjacent microdomain to bind to other partner(s). The NMDAR GluN2B subunit is a key target of CaMKIIα in the postsynaptic density (Strack and Colbran, 1998; Gardoni et al., 1998; Leonard et al., 1999). Its binding with CaMKIIα is upregulated by Ca2+ (Leonard et al., 1999; Colbran, 2004; Bayer et al., 2006) as opposed to the downregulation of the CaMKIIα binding to mGluR5 in response to Ca2+. Indeed, adding Ca2+ (2.5 μM) substantially increased the amount of CaMKIIα co-precipitated with GluN2B in striatal lysates (Fig. 5A). To determine whether mGluR5 regulates CaMKIIα-GluN2B interactions, we monitored the interaction rate of the two proteins in response to pharmacological activation of mGluR5 with DHPG. Applying DHPG at different concentrations (1–100 μM, 10 min) induced a concentration-dependent increase in the CaMKIIα-GluN2B interaction in striatal slices (Fig. 5B). This increase was rapid and reversible (Fig. 5C). Thus, mGluR5 signals facilitate the association of CaMKIIα with GluN2B. This mGluR5-dependent association is further supported by the results from subsequent pharmacological studies. Pretreatment with MTEP (10 μM, 30 min prior to DHPG) largely reduced the DHPG-stimulated formation of CaMKIIα-GluN2B complexes (Fig. 5D). Similar to MTEP, KN93 (20 μM), an inhibitor that inhibits activation of CaMKII by preventing the CaM binding, reduced the DHPG effect, while KN92 (20 μM), an inactive analogy of KN93, did not (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5. Effects of DHPG on CaMKIIα-GluN2B interactions in rat striatal neurons.

A, Effects of Ca2+ on the association of CaMKIIα with GluN2B in rat striatal lyses. Ca2+ was added to lyses to a final concentration of 2.5 μM for 10 min. Note a robust increase in co-precipitating levels of CaMKIIα in Ca2+-treated samples. B, Concentration-dependent effects of DHPG (10 min) on CaMKIIα-GluN2B interactions in striatal slices. C, Time-dependent effects of DHPG on CaMKIIα-GluN2B interactions in striatal slices. DHPG was incubated in slices at 100 μM for different durations (10, 30, or 60 min) prior to sample collections. D, Effects of MTEP, KN93, or KN92 on the DHPG-stimulated CaMKIIα-GluN2B interactions in striatal slices. MTEP (10 μM), KN93 (20 μM), or KN92 (20 μM) was applied 30 min prior to and during DHPG incubation (100 μM, 10 min). Coimmunoprecipitation (IP) with solubilized striatal synaptosomal proteins was performed to detect interactions between CaMKIIα and GluN2B. Precipitated proteins were visualized by immunoblots (IB) with indicated antibodies. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3–6 per group). *p < 0.05 versus vehicle. +p < 0.05 versus vehicle + DHPG.

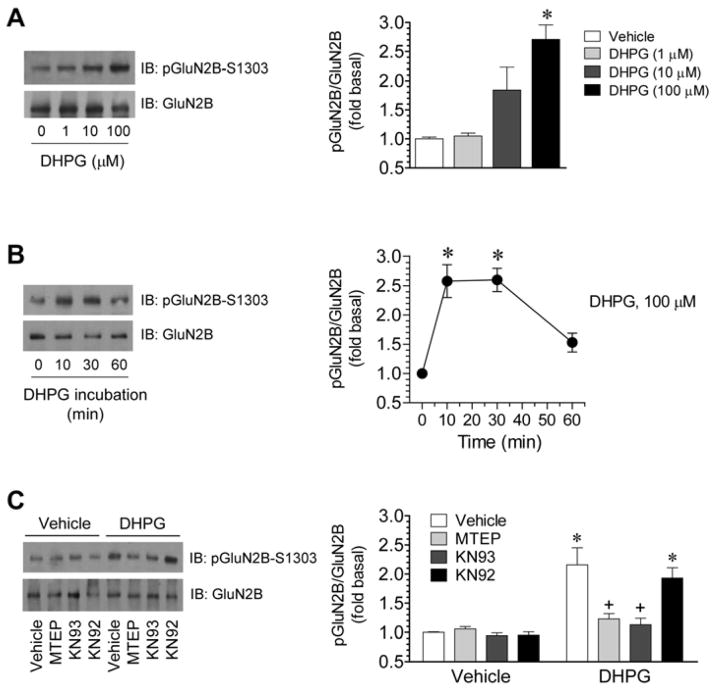

Activating mGluR5 enhances GluN2B phosphorylation

CaMKII phosphorylates GluN2B at a specific serine site (S1303) located in the intracellular C-terminal tail (Omkumar et al., 1996; Strack et al., 2000). To determine whether the mGluR5-upregulated binding of CaMKIIα to GluN2B translates to a consequential modification of GluN2B phosphorylation at the CaMKII-sensitive site, we monitored S1303 phosphorylation in response to DHPG. In striatal slices, using a phospho- and site-specific antibody, we found that DHPG (1–100 μM, 10 min) concentration-dependently increased S1303-phosphorylated GluN2B (pGluN2B) protein levels (Fig. 6A). The effect of DHPG was dynamic (Fig. 6B). The maximal increase in S1303 phosphorylation was seen 10 min after DHPG application (100 μM). At 60 min, the increase dramatically declined and was no longer significantly different from the basal level. MTEP (10 μM) was able to considerably lower the S1303 phosphorylation induced by DHPG (Fig. 6C). Similarly, KN93 (20 μM) prevented DHPG from stimulating S1303 phosphorylation, while KN92 (20 μM) did not (Fig. 6C). There were no changes in total GluN2B protein levels in response to all drug treatments (Fig. 6A–C). These results demonstrate the linkage of mGluR5 to GluN2B, leading to an increase in the CaMKII-mediated S1303 phosphorylation. Remarkably similar kinetics of the two sequential events (increased CaMKIIα-GluN2B binding and enhanced S1303 phosphorylation) in response to mGluR5 stimulation is noteworthy.

Figure 6. Effects of DHPG on GluN2B phosphorylation in rat striatal slices.

A, Concentration-dependent effects of DHPG (10 min) on GluN2B-S1303 phosphorylation. Note that DHPG concentration-dependently increased S1303 phosphorylation. B, Time-dependent effects of DHPG on GluN2B-S1303 phosphorylation. DHPG was incubated in striatal slices at 100 μM for different durations (10, 30, or 60 min). Note a dynamic and reversible change in S1303 phosphorylation following DHPG stimulation. C, Effects of MTEP, KN93, or KN92 on the DHPG-stimulated GluN2B-S1303 phosphorylation. MTEP (10 μM), KN93 (20 μM), or KN92 (20 μM) was applied 30 min prior to and during DHPG incubation (100 μM, 10 min). After drug treatment, slices were collected for preparing synaptosomal proteins for immunoblot analysis of pGluN2B-S1303 proteins with a phospho- and site-specific antibody. Representative immunoblots are shown left to quantification data. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3–6 per group). *p < 0.05 versus vehicle. +p < 0.05 versus vehicle + DHPG.

Discussion

The present study originally aimed to search for new binding partners of mGluR5. We found that CaMKIIα in the inactive form constitutively bound to mGluR5 CT. This binding was downregulated by Ca2+. Ca2+ also promoted CaM to bind to the same site hosting mGluR5 and competitively reduced CaMKIIα binding to the receptor. In addition, we found that the CaMKIIα binding to GluN2B was increased simultaneously in response to mGluR5 activation. Phosphorylation of a CaMKII-sensitive site on GluN2B was increased in parallel. These data establish a previously unrecognized synaptic model in which mGluR5 triggers Ca2+ to dissociate preformed CaMKIIα from mGluR5 and to recruit active CaMKIIα to GluN2B. The latter seems to form a biochemical process to link mGluR5 to NMDARs.

The membrane topology of mGluR5 is characterized by a long intracellular CT domain, which is believed to harbor robust protein-protein interactions. Indeed, in this study, we identified a new binding partner of mGluR5. A synapse-enriched kinase (CaMKIIα) directly interacts with mGluR5 CT. This interaction is selective to CaMKIIα since CaMKIV did not bind to mGluR5. CaMKIIα also binds to mGluR1a CT, but at a different site (Jin et al., 2013). Of note, the mGluR5 CT region where CaMKIIα binds to was also open to CaM (Choi et al., 2011). This forms a basis for CaM and CaMKIIα to compete with each other for binding to mGluR5. Another evident characteristic of the CaMKIIα-mGluR5 interaction is its sensitivity to Ca2+. Unlike the previously reported upregulation of interactions among other CaMKIIα binding partners, including CaM (Minakami et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2011) and GluN2B (Leonard et al., 1999; Colbran, 2004; Bayer et al., 2006), an inhibition of CaMKIIα associations with mGluR5 was surprisingly induced by Ca2+. Based on this inhibition, a new stepwise synaptic model seems to be discovered. Under the basal condition, inactive CaMKIIα binds to mGluR5 and accumulates the kinase at the perisynaptic site. When cytoplasmic Ca2+ rises, inactive CaMKIIα becomes active and thereby loses its affinity for mGluR5 and dissociates from the receptor. After CaMKIIα dissociates from mGluR5, Ca2+-activated CaM occupies the binding site and prevents the further accessibility of CaMKIIα to the site. Meanwhile, active CaMKIIα enhances its binding to GluN2B to phosphorylate S1303, although whether CaMKIIα that binds to GluN2B is the same pool of CaMKIIα that was dissociated from mGluR5 is unclear at this stage. Nevertheless, the mGluR5- and Ca2+-gated interaction between CaMKIIα and GluN2B seems to suggest an activity-dependent model linking mGluR5 to NMDARs, in which CaMKIIα plays a central role. This model is in accordance with the early observations that DHPG readily activated CaMKII in striatal and hippocampal neurons (Choe and Wang, 2001; Mockett et al., 2011), although the source of the Ca2+ that drives CaMKII activation in hippocampal neurons seems to be independent of the classical mGluR1/5-PLC pathway and needs further investigations (Mockett et al., 2011).

Although not explored in this study, numerous reports have documented a positive coupling from group I mGluRs to NMDARs. A short period of group I mGluR activation potentiated NMDAR-mediated currents, especially those currents evoked by exogenous NMDA application. This potentiation was recorded in Xenopus oocytes (Skeberdis et al., 2001) and neurons from many brain regions, including the hippocampus (Doherty et al., 2000; Mannaioni et al., 2001; Benquet et al., 2002; Kotecha et al., 2003; Grishin et al., 2004), striatum (Pisani et al., 1997; 2000; 2001), cortex (Attucci et al., 2001; Heidinger et al., 2002), thalamus (Awad et al., 2000), hypothalamus (Huang and van den Pol, 2007), and spinal cord (Yang et al., 2011), although depression of NMDAR currents was also seen in hippocampal neurons (Ireland and Abraham, 2009). The positive mGluR5-NMDAR interaction plays an essential role in normal glutamatergic transmission and synaptic plasticity, and malfunction of the interplay is linked to the pathogenesis of a variety of neurological disorders, including pain, addiction, neurodegenerative diseases and neurotoxicity (Bonsi et al., 2008). The group I mGluR regulation of NMDARs is thought to act through a postsynaptic mechanism (Huang and van den Pol, 2007), although precise underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. Our data suggest an attractive signaling pathway linking mGluR5 to NMDARs. Through this pathway, mGluR5 signals enhance phosphorylation of GluN2B S1303, the first identified and principal phosphorylation site by CaMKII (Omkumar et al., 1996; Mao et al., 2011). Since S1303 phosphorylation augmented NMDAR currents (Liao et al., 2001), the mGluR5-upregulated S1303 phosphorylation seen in the current study should have a positive functional consequence.

The mGluR5 antagonist MPEP but not the mGluR1 antagonist LY367385 or CPCCOEt suppressed the DHPG-induced potentiation of NMDAR responses to exogenous application of NMDA in hippocampal (Mannaioni et al., 2001), striatal (Pisani et al., 2001), cortical (Attucci et al., 2001), and thalamic (Awad et al., 2000) neurons (but Heidinger et al., 2002). MPEP also blocked synaptically-evoked NMDAR-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents in hypothalamic melanin-concentrating hormone neurons, while LY367385 did not (Huang and van den Pol, 2007). In mGluR1 knockout mice, DHPG potentiated NMDAR currents in striatal neurons, while this potentiation was absent in mGluR5 knockout mice (Pisani et al., 2001). Additionally, the mGluR5 agonist CHPG and the mGluR5 positive allosteric modulator ADX-47273 augmented striatal and hippocampal NMDA responses (Rosenbrock et al., 2010; Pisani et al., 2001). These data collectively support a subtype selective role of mGluR5 in processing the potentiation of NMDARs (Bonsi et al., 2008). Our data show that the binding of CaMKIIα to mGluR1 and mGluR5 was differentially regulated by Ca2+: the CaMKIIα-mGluR1 binding was upregulated (Jin et al., 2013) whereas the CaMKIIα-mGluR5 binding was downregulated (this study) in response to Ca2+. In addition, CaM binds to mGluR5 but not mGluR1 (Choi et al., 2011). Thus, mGluR5 rather than mGluR1 is preferentially positioned to potentiate NMDAR activity, in which CaMKIIα plays a bridging role.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants DA10355 (J.Q.W.) and MH61469 (J.Q.W.). We thank Dr. Howard Schulman, Dr. K. Ulrich Bayer and Dr. Yasunori Hayashi for providing CaMKIIα WT and mutant vectors.

Abbreviations

- ATP

adenosine-5′-triphosphate

- CaMKII

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- CaM

calmodulin

- CT

C terminus

- DHPG

(RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine

- EGTA

ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptors

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- HEPES

hydroxyethyl piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- LDS

lithium dodecyl sulfate

- mGluR

metabotropic glutamate receptor

- MTEP

3-((2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-4-yl)ethynyl)pyridine hydrochloride

- NMDAR

NMDA receptors

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Attucci S, Carla V, Mannaioni G, Moroni F. Activation of type 5 metabotropic glutamate receptors enhances NMDA responses in mice cortical wedges. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:799–806. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad H, Hubert GW, Smith Y, Levey AI, Conn PJ. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 has direct excitatory effects and potentiates NMDA receptor currents in neurons of the subthalamic nucleus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7871–7879. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-07871.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard L, Groc L. Glutamate receptor dynamics and protein interaction: lessons from the NMDA receptor. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;48:298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer KU, LeBel E, McDonald GL, O’Leary H, Schulman H, Koninck PD. Transition from reversible to persistent binding of CaMKII to postsynaptic sites and NR2B. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1164–1174. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3116-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benquet P, Gee CE, Gerber U. Two distinct signaling pathways upregulate NMDA receptor responses via two distinct metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9679–9686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09679.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonsi P, Platania P, Martella G, Madeo G, Vita D, Tassone A, Bernardi G, Pisani A. Distinct roles of group I mGlu receptors in striatal function. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:392–395. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe ES, Wang JQ. Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors control phosphorylation of CREB, Elk-1 and ERK via a CaMKII-dependent pathway in rat striatum. Neurosci Lett. 2001;313:129–132. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02258-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KY, Chung S, Roche KW. Differential binding of calmodulin to group I metabotropic glutamate receptors regulates receptor trafficking and signaling. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5921–5930. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6253-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbran RJ. Targeting of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem J. 2004;378:1–16. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbran RJ, Soderling TR. Calcium/calmodulin-independent autophosphorylation sites of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Studies on the effect of phosphorylation of threonine 305/306 and serine 314 on calmodulin binding using synthetic peptides. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11213–11219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty AJ, Palmer MJ, Bortolotto ZA, Hargreaves A, Kingston AE, Ornstein PL, Schoepp DD, Lodge D, Collingridge GL. A novel, competitive mGlu(5) receptor antagonist (LY344545) blocks DHPG-induced potentiation of NMDA responses but not the induction of LTP in rat hippocampal slices. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:239–244. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enz R. The trick of the tail: protein-protein interactions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Bioessays. 2007;29:60–73. doi: 10.1002/bies.20518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enz R. Metabotropic glutamate receptors and interacting proteins: evolving drug targets. Curr Drug Targets. 2012;13:145–156. doi: 10.2174/138945012798868452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagni L. Diversity of metabotropic glutamate receptor-interacting proteins and pathophysiological functions. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;970:63–79. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0932-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardoni F, Caputi A, Cimino M, Pastorino L, Cattabeni F, Di Luca M. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II is associated with NR2A/B subunits of NMDA receptor in postsynaptic densities. J Neurochem. 1998;71:1733–1741. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71041733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishin AA, Gee CE, Gerber U, Benquet P. Differential calcium-dependent modulation of NMDA currents in CA1 and CA3 hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Neurosci. 2004;24:350–355. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4933-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo ML, Fibuch EE, Liu XY, Choe ES, Buch S, Mao LM, Wang JQ. CaMKIIα interacts with M4 muscarinic receptors to control receptor and psychomotor function. EMBO J. 2010;29:2070–2081. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidinger V, Manzerra P, Wang XQ, Strasser U, Yu SP, Choi DW, Behrens MM. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 1-induced upregulation of NMDA receptor current: mediation through the Pyk2/Src-family kinase pathway in cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5452–5461. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05452.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, van den Pol AN. Rapid direct excitation and long-lasing enhancement of NMDA response by group I metabotropic glutamate receptor activation of hypothalamic melanin-concentrating hormone neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11560–11572. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2147-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireland DR, Abraham WC. Mechanisms of group I mGluR-dependent long-term depression of NMDA receptor-mediated transmission at schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:1375–1385. doi: 10.1152/jn.90643.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin DZ, Guo ML, Xue B, Fibuch EE, Choe ES, Mao LM, Wang JQ. Phosphorylation and feedback regulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 by CaMKII. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3402–3412. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3192-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly PT, McGuinness TL, Greengard P. Evidence that the major postsynaptic density protein is a component of a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:945–949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerner JA, Standaert DG, Penney JB, Jr, Young AB, Landwehrmeyer GB. Expression of group I metabotropic glutamate receptor subunit mRNAs in neurochemically identified neurons in the rat neostriatum, neocortex, and hippocampus. Mol Brain Res. 1997;48:259–269. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotecha SA, Jackson MF, Al-Mahrouki A, Roder JC, Orser BA, MacDonald JF. Co-stimulation of mGluR5 and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors is required for potentiation of excitatory synaptic transmission in hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27742–27749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301946200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwajima M, Hall RA, Aiba A, Smith Y. Subcellular and subsynaptic localization of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors in the monkey subthalamic nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 2004;474:589–602. doi: 10.1002/cne.20158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Lee J, Choi KY, Hepp R, Lee JY, Lim MK, Chatani-Hinze M, Roche PA, Kim DG, Ahn YS, Kim CH, Roche KW. Calmodulin dynamically regulates the trafficking of the metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12575–12580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712033105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard AS, Lim IA, Hemsworth DE, Horne MC, Hell JW. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II is associated with the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3239–3244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao GY, Wagner DA, Hsu MH, Leonard JP. Evidence for direct protein kinase-C mediated modulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor current. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:960–964. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.5.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XY, Mao LM, Zhang GC, Papasian CJ, Fibuch EE, Lan HX, Zhou HF, Xu M, Wang JQ. Activity-dependent modulation of limbic dopamine D3 receptors by CaMKII. Neuron. 2009;61:425–438. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lujan R, Nusser Z, Roberts JD, Shigemoto R, Somogyi P. Perisynaptic location of metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR1 and mGluR5 on dendrites and dendritic spines in the rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:1488–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannaioni G, Marino MJ, Valenti O, Traynelis SF, Conn PJ. Metabotropic glutamate receptors 1 and 5 differentially regulate CA1 pyramidal cell function. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5925–5934. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-05925.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao LM, Guo ML, Jin DZ, Fibuch EE, Choe ES, Wang JQ. Posttranslational modification biology of glutamate receptors and drug addiction. Front Neuroanat. 2011;5:19. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2011.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakami R, Jinnai N, Sugiyama H. Phosphorylation and calmodulin binding of the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 (mGluR5) are antagonistic in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20291–20298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mockett BG, Guevremont D, Wutte M, Hulme SR, Williams JM, Abraham WC. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II mediates group I metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent protein synthesis and long-term depression in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7380–7391. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6656-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswende CM, Conn PJ. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: physiology, pharmacology, and disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:295–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omkumar RV, Kiely MJ, Rosenstein AJ, Min KT, Kennedy MB. Identification of a phosphorylation site for calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in the NR2B subunit of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31670–31678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petralia RS. Distribution of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors on neurons. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:267120. doi: 10.1100/2012/267120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A, Calabresi P, Centonze D, Bernardi G. Enhancement of NMDA responses by group I metabotropic glutamate receptor activation in striatal neurons. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:1007–1014. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A, Bernardi G, Bonsi P, Centonze D, Giacomini P, Calabresi P. Cell-type specificity of mGluR activation in striatal neuronal subtypes. Amino Acids. 2000;19:119–129. doi: 10.1007/s007260070040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A, Gubellini P, Bonsi P, Conquet F, Picconi B, Centonze D, Barnardi G, Calabresi P. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 mediates the potentiation of N-methyl-D-aspartate responses in medium spiny striatal neurons. Neuroscience. 2001;106:579–587. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00297-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbrock H, Kramer G, Hobson S, Koros E, Grundl M, Grauert M, Reymann KG, Schroder UH. Functional interaction of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 and NMDA-receptor by a metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 positive allosteric modulator. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;639:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeberdis VA, Lan J, Opitz T, Zheng X, Bennett MV, Zukin RS. mGluR1-mediated potentiation of NMDA receptors involves a rise in intracellular calcium and activation of protein kinase C. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:856–865. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack S, Colbran RJ. Autophosphorylation-dependent targeting of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II by the NR2B subunit of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20689–20692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.20689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack S, McNeill RB, Colbran RJ. Mechanism and regulation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II targeting to the NR2B subunit of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23798–23806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001471200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallaksen-Greene SJ, Kaatz KW, Romano C, Albin RL. Localization of mGluR1a-like immunoreactivity and mGluR5a-like immunoreactivity in identified population of striatal neurons. Brain Res. 1998;780:210–217. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa CM, Standaert DG, Landwehrmeyer GB, Penney JB, Jr, Young AB. Differential expression of mGluR5 metabotropic glutamate receptor mRNA by rat striatal neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1995;354:241–252. doi: 10.1002/cne.903540207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa CM, Standaert DG, Young AB, Penney JB., Jr Metabotropic glutamate receptor mRNA expression in the basal ganglia of the rat. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3005–3018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-03005.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynelis SF, Wollmuth LP, McBain CJ, Menniti ES, Vance KM, Ogden KK, Hansen KB, Yuan H, Myers SJ, Dingledine R. Glutamate receptor ion channels: structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:405–496. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K, Takeuchi K, Wei F, Dubner R, Ren K. Activation of group I mGlu receptors contributes to facilitation of NMDA receptor membrane current in spinal dorsal horn neurons after hind paw inflammation in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;670:509–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]