Abstract

Purpose

To explore/identify patient perspectives regarding seeking, delaying, and avoiding health care services, particularly barriers and facilitators.

Design

Face-to-face interviews with health plan survey respondents.

Setting

An integrated health plan providing comprehensive care to 480,000 people in Oregon and Washington.

Participants

Willing respondents randomly selected to maximize heterogeneity within the following strata: gender, health care utilization, and self-reported alcohol consumption (indicator of health practices). Participants were 75 men and 75 women (150 total), 21–64 years old, with ≥12 months of health plan membership.

Method

Participants were recruited by letter (52.5% agreed). Data collection stopped when planned interviews were completed; saturation (the point at which additional interviews were not producing novel information) was achieved for key study questions. Semi-structured interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded. Reviews of codes related to care seeking and feelings/attitudes about providers produced common themes.

Results

Facilitators of care seeking included welcoming staff, collaborative relationships with providers, and education about the value of preventive care. Barriers included costs, time needed for appointments, and cumbersome processes. Some participants delayed procedures, some avoided care until absolutely necessary, others framed care as routinely necessary.

Conclusion

Increasing comfort, improving appointment and visit-related processes, having positive patient-physician relationships, and enhancing communication and clinician-provided education may facilitate appropriate use of preventive services. Further research is needed with larger, representative, samples to evaluate findings.

Keywords: Attitudes & beliefs, health care avoidance, barriers to health care, health care seeking, clinician-patient relationships, qualitative research

Indexing Key Words: Manuscript format: research, Research purpose: exploratory, Study design: qualitative, Outcome measure: not applicable, Setting: clinical/healthcare, Health focus: care seeking, Strategy: not applicable, Target population: adults, Target population circumstances: Insured

Purpose

With the advent of health care reform,1 including greater emphasis on use of primary and preventive care, it is increasingly important to understand factors at the patient level that facilitate or impede appropriate use of routine health care services. In general, health-related attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge predispose people to use or avoid health care.2;3 For example, people who are skeptical about medical care are less likely to visit the doctor or receive routine preventive services.4 Similarly, less educated patients are less likely to seek preventive care.5 In addition, certain stigmatized health-related practices (e.g., excessive alcohol consumption, smoking) may increase the likelihood that people will avoid care, while at the same time increasing their risks.6–10 Need-based factors (e.g., illness or poor health) are among the most important and immediate antecedents for seeking health care.2;11–15 It is important to identify and understand both the factors that facilitate preventive and routine service and promote better health, as well as those that present barriers to such use. Known facilitators of preventive and/or routine care include having health insurance,2;3;16;17 a regular clinician,18–21 and good clinician-patient relationships.22 To date, however, few studies have systematically examined perceived barriers to, and facilitators of, service seeking. Using interview data from a larger study examining gender, health-related attitudes and practices (including drinking patterns), and use of health services, we conducted qualitative analyses to identify and describe those participant attitudes and feelings related to clinicians and health care seeking that foster or impede use of preventive and routine services.

Design

From October 2002 through mid-April 2003 we conducted a survey of Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW) members aged 18–64 assessing attitudes, health beliefs, and health-related practices. Questionnaires were mailed to a stratified random sample of 15,000 health plan members (8500 women and 6500 men) who, prior to sample extraction, had at least 12 months of health plan membership. A total of 7884 health plan members responded to the questionnaire, 4477 of whom agreed to be contacted for a face-to-face interview. Survey respondents differed significantly from non-respondents on the following characteristics: They were older (mean 46.5 ± 11.5 vs. 40.9 ± 11.5 years), less likely to have Medicaid coverage (3.5% vs. 4.8%), more likely to have been health plan members for longer periods (averaging 155.9 ± 113 months vs. 123.7 ± 98 months), had more prior-year outpatient visits (mean 6.5 ± 8.0 vs. 5.0 ± 6.9), had slightly fewer months of dental plan membership (mean 5.2 ± 6.3 vs. 5.0 ± 6.2), and were more likely to be female (58% responded) than male (46% responded). Data were not available for non-respondents for comparisons of BMI, household income, or educational level. Respondents who agreed to be contacted for an interview were slightly older than those who did not want to be contacted (mean age = 47.10 years vs. 45.68 years); equally likely to be insured through Medicaid, and had greater numbers of outpatient visits in the prior year to the survey than those who did not want to be contacted. Additional details about the parent study, questionnaire design, sampling methods, and characteristics of sample respondents have been summarized elsewhere.8

From April 2003 through November 2003, we mailed recruitment letters to 316 potential recruits, selected to represent a full range of (a) alcohol consumption patterns, (b) health care use according to health plan records and, equally, (c) women and men. This strategy was used to increase the heterogeneity of the sample across these domains.24 Recruitment letters provided additional information about the qualitative study and offered a $50 gift card to a local shopping center for participation in the 1-hour interview. We were unable to reach 27% of the participants we approached for recruitment; of those contacted, 35% refused to participate. Overall participation was 52.5%: 150 participants gave informed consent and completed interviews.

Setting

The study was conducted at Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW), a not-for-profit, prepaid group-practice integrated health plan serving about 480,000 members in Southwest Washington and Northwest Oregon states. The demographic characteristics of health plan members closely mirror those of its service area. KPNW provides a full range of inpatient and outpatient medical, mental health, and addiction treatment services to its members. The KPNW Institutional Review Board approved and monitored this study.

Participants

Interview participants (75 women, 75 men) were 21 to 64 years of age, with an average age of 46.2 years (SD = 12.4). About 90% of participants were white, consistent with the surrounding geographic area and health plan membership; 2% reported mixed racial heritage, 3.3% indicated black or African American race, 0.07% identified as Asian/Pacific Islanders, 0.07% reported American Indian/Alaska Native heritage, and 1.3% reported Hispanic ethnicity. See Table 1 for additional demographic information. Insert Table 1 about here

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristic | Men n = 75 |

Women n = 75 |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 46.9 (12.5) | 45.35(12.2) |

| White race/ethnicity, % | 85.5 | 86.9 |

| Married or living as married % | 65.3 | 62.6 |

| Educational level, % | ||

| Less than High School graduate | 4 | 0** |

| High School grad or equivalent | 12 | 10.6 |

| Some college/technical | 37.3 | 44 |

| College graduate | 17.3 | 22.6 |

| Postgraduate | 16 | 22.6 |

| Household income, adjusted for number of persons supported, % | ||

| $12,500 or under | 22.6 | 8 |

| $12,501 to $18,750 | 14.6 | 12 |

| $18,751 to $27,500 | 21.3 | 22.6 |

| $27,501 to $37,500 | 16 | 18.6 |

| Over $37,500 | 21.3 | 21.3 |

| Body Mass Index, % | ||

| under 25.0 | 24 | 38.6 |

| 25.0 to 29.9 | 40 | 30.6 |

| 30 or over | 36 | 30.6 |

| Smoking status, % | ||

| Current smoker | 18.6 | 18.6 |

| Former smoker | 33.3 | 32 |

| Never smoked | 48 | 48 |

| Drinking status, % | (n = 74) | (n = 75) |

| Lifelong abstainer | 14.6 | 13.3 |

| Former drinker | 21.3 | 20 |

| Current drinkers: | ||

| 0.5–29 drinks/month | 30.6 | 25.3 |

| 30–59 drinks/month | 12 | 30.6 |

| 60–89 drinks/month | 10.6 | 6.6 |

| ≥90 drinks/month | 9.3 | 4 |

| Frequency of heavy drinking among current drinkers, % | (n = 48) | (n = 50) |

| Never | 18.8 | 38 |

| Less than monthly | 14.5 | 34 |

| Monthly | 33 | 16 |

| Weekly | 25 | 10 |

| Daily or almost daily | 8.3 | 2 |

Method

Interviews

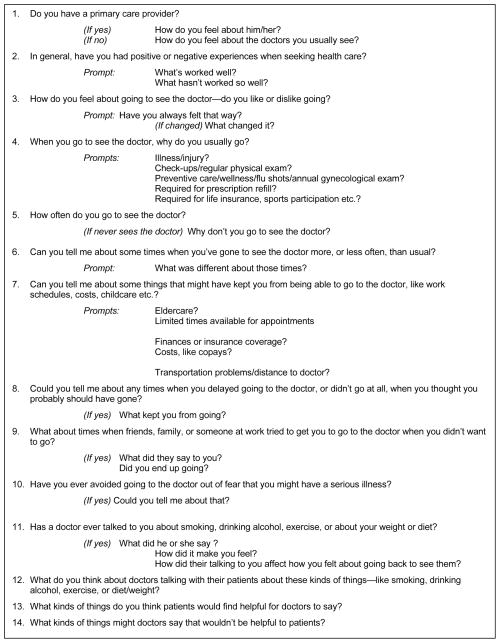

Interviews averaged about 60 minutes and were conducted in-person by trained interviewers using a semi-structured interview guide. The guide addressed health care seeking or avoidance as well as relationships to health-related practices (alcohol consumption, smoking, diet/weight management, and exercise). Questions asked depended on participants’ responses to previous interview questions and responses to the mailed questionnaire (e.g., lifelong abstainers were not asked about current or past drinking practices). Interviews were audiorecorded and then transcribed. A subset of questions from the interview guide, with corresponding prompts, are included in Figure 1. The full interview guide is available, upon request, from the corresponding author. Insert Figure 1 about here

Figure 1.

Example questions from in-depth interview guide.

Qualitative analyses

We used Atlas.ti25 software to code transcribed interview text. Investigators reviewed a subset of interviews to develop a descriptive coding scheme, which was then applied to additional interviews, revised, and refined. When finalized, all codes were clearly defined, and weekly reliability sessions were held to discuss, identify, and resolve any discrepancies across coders. Study investigators and interviewers coded all 150 transcripts. Check coding of 9 primary codes in 10% of the transcripts (208 text passages) determined that primary coders applied codes accurately 92.8% of the time. Once transcripts were coded, we used single-code queries to create reports of text from codes that addressed (1) attitudes and feelings related to visiting the doctor; (2) barriers and facilitators of care seeking; (3) fear and anxiety about the doctor, procedures, and diagnosis; and (4) reasons for avoiding or seeking health care. We reviewed each query to identify (a) descriptive themes in the text,26;27 (b) commonly reported barriers to and facilitators of health care use, (c) feelings about seeking care and clinicians, and (d) feelings and experiences related to the process of seeking care. Because this is an exploratory study, criteria for themes included frequent endorsement as well as less frequently endorsed ideas that appeared to be important to the participants who mentioned them or were likely to be greater barriers for individuals receiving care outside an integrated health maintenance organization. Illustrative quotes were chosen based on how well they articulated a theme or presented an interesting idea.

Results

Two of the authors [KJ and CG] identified 13 themes, which were organized within five overarching categories: Clinician-patient relationships, financial barriers, time barriers, cumbersome processes and interactions with the system, and timing of/delays in care seeking. Examinations of results by drinking status categories suggested that themes were cross-cutting rather than specific to drinking status, thus we have presented overall themes here. Occasionally, participants replied to questions other than what was asked immediately prior to their response, most often continuing a previous topic. Such circumstances have been interpreted in the context of the larger interview. We have included counts of the number of individuals expressing particular ideas and themes. It is important to note, however, that because these are emergent themes generated as part of an exploratory interview (i.e., they were provided in response to general questions rather than specific questions assessing each theme), that they represent undercounts of the numbers of individuals who would endorse each theme if they were specifically asked if they agreed with that theme or idea. Categories and themes are detailed below.

Patient-clinician relationships

Participants mentioned that they preferred seeing clinicians who took the time to listen, helped to educate them, and worked cooperatively. Also, some participants stated they were more likely to see their clinician when the clinician was caring, considerate, collaborative, and took time to develop a positive relationship.

Theme 1: Caring, considerate approach of clinician is valued

Participants (n = 18) mentioned being more likely to see their clinician if they were perceived as friendly and understanding and if they actively listened to patients’ concerns, and took a positive approach. Participants particularly appreciated clinicians who were compassionate and considerate in addressing sensitive health care issues.

Interviewer: Is there anything that the doctors or clinic staff could do to make it a more comfortable experience?

Participant: …Just being friendly, actually. Showing concern. Listening, [even] if they have something to say to you.

Theme 2: Collaborative and holistic approaches are appreciated

Patients (n = 11) liked clinicians who listened, took their time during appointments, were open to in-depth discussions about the positives and negatives of treatments, and who adopted a holistic approach.

I definitely think it’s good if the doctor has time to sit down and actually talk to you about your health practices and give you options. I think it’s really important that they explain to you what they want to do and….give you those choices and really inform you. And take an interest in your general health…You know, that they look at the person kind of holistically.

Theme 3: Clinicians need to take time to develop a relationship with patients

Participants (n = 20) also indicated they were more likely to see their clinician if they felt they had a good relationship with their clinician, if their clinician’s personality was similar to their own, they got along well, and if the relationship was based upon respect and warmth.

Interviewer: Is there anything that you can think of on the other side that doctors or their staff could do to make it a more likely event that they [patients who avoid the doctor] would come in?

Participant: Yeah. Sure. Develop a relationship. Treat people both with respect and with warmth. Doctor [NAME] asks me about things about my family...I have only known this guy for a year and a half or less. He knows more about me than all of the other people combined over the years. Go put a camera on Doctor [NAME] and you’ll see how to do it.

Good relationships with clinicians fostered communication that participants felt increased the ability of clinicians to provide good quality, appropriate care.

Interviewer: So you’re talking about the relationship between the patient and the provider being fairly significant?

Participant: Definitely. If you’re not comfortable talking with them then they aren’t going to get good information.

Theme 4: People need education to help them assess their health and to understand the importance of preventive care

Participants (n = 22) also pointed out the importance of clinicians taking the time to educate patients about the value of preventive services, about the health conditions they have, and what they need to be aware of when making decisions about whether and when to seek health care.

People need to be educated. If they don’t know then they’re going to either continue to get worse or they are going to continue not knowing. I just think that education is a huge key.

Some participants felt that providing education about preventive health care was particularly important for young people who may not realize the importance of such services given their age.

…with preventive health…sometimes people don’t know when they need to see a doctor or what they need to see a doctor for…if you can start children realizing that to go to the doctor is not a negative event. If you start at the bottom, people will change, but you can’t start with an eighty year old and improve their health…

Participants also mentioned that patients needed to be educated about the benefits of routine health assessments, early detection, and the underlying reasons for different assessments at different ages.

…show some kind of statistics. You know, the benefits of getting regular checkups. Maybe send an email out, or something, that says these are the reasons you ought to get a checkup at this age and this age, because these are things to watch out for. Explain that if you catch something early enough, it’s a lot better than catching it later.

On the other hand, some people may fail to seek services on the basis of health-related practices, preventing them from receiving such education. We found evidence that seven participants avoided the doctor because of weight, diet or fitness level, three because of alcohol drinking practices, and two because of smoking.

Financial barriers

Theme 5: Costs present barriers

Financial pressures affected service seeking for some individuals (n = 11), even in the context of a pre-paid health plan charging minimal copays (typically $10 to $15) or no copays (e.g., for influenza vaccines) for most services. Participants mentioned several cost-related factors that would encourage them to use preventive services, including lower co-pays, or insurance premiums linked to completing preventive services. For example:

If you incite them by, “If you don’t get your annual preventative care, your premium is more the next year.” Money speaks to people….Something that they see a payback to doing it. I went to the doctor, so I got something.

Time barriers

Theme 6: Time commitment is a barrier

Time was a significant barrier for some participants (n = 28). The time that it took to see clinicians was a barrier, and given the commitment patients made to make the visit, participants wished their clinicians would spend more time with them during appointments. Some participants reported that the time and hassle associated with visiting the clinician was problematic, especially when it required time off from work. They particularly disliked occasions when clinicians were late for appointments.

I generally don’t like to go see a doctor any more than I have to, just because of time. I don’t like to waste time.

Overall, patients wanted to spend more time with their clinicians and less time waiting.

When clinicians did spend even a little “extra” time, patients saw it as an indicator that the clinician cared.

He seems to care. It seems like he gives that extra couple of minutes with you. You’re not just in and out. It just seems like he gives a little more care.

Some participants noted a lack of equity between patients and clinicians in terms of waiting times and expectations, and saw this as a significant problem:

I know one thing that I don’t like and that I know everyone doesn’t like it, and that’s coming in when you have an appointment and then having to wait in the waiting room for a half hour past your appointed time. I don’t think that’s fair. We can’t be late for appointments or miss them or we get a charge, and yet the doctor can keep you cooling your heels in his waiting room for as long as he feels like he can. I think that consideration should go both ways.

Processes and interactions with the system

Theme 7: Welcoming attitudes of staff make people feel more comfortable in clinic environments

Participants (n = 21) also mentioned that welcoming staff who promoted comfort in clinic environments facilitated care seeking, as did receiving friendly reminders about need for and timing of preventive services and the ease or difficulty of navigating systems. For example, participants reported that they would be more willing to see their clinician if the health care environment was more welcoming and if they experienced better customer service. In general, participants indicated that greater feelings of safety and comfort, and good customer service, made it easier for them to seek care:

I would say that as far as the medical staff is concerned, to make people want to come in, or less reluctant to come in, would be the kindness and the sense that you are not bothering us. That is what we’re here for and that is what we want to do….Almost a kind of customer service approach.

-----

Just talk to them a little bit, or something….Or, maybe say, “It’s gonna be exactly 15 more minutes. There’s a cafeteria downstairs. Here’s a wooden nickel; go get a cup of coffee.” Maybe a little freebie from the cafeteria, or something…

Theme 8: Patients like reminders

Participants (n = 27) mentioned that they would be more likely to visit the clinician if they received reminders when the time came for a screening or other regular preventive service.

Maybe if I’m getting older they can send me a letter saying, “You don’t have a primary [care clinician],” like they do with immunizations… At a certain age point you should get this checked more regularly. How often? Every year.

Theme 9: Patients dislike cumbersome processes and need to be assertive to overcome them

Some participants (n = 13) mentioned disliking cumbersome processes, such as making appointments and filling prescriptions. In general, participants appeared more willing to seek care when it was easy for them to navigate the system. When it was not simple, or when patients were not assertive, they could be easily discouraged:

…I am persistent and aggressive…[I] can get what I need from health care providers...I think that there are an awful lot of people that due to lack of education, lack of assertive personality, or whatever, that don’t get their needs met, and there should be a way for the systems to help them get their needs met. For an elderly person, the telephone system has to be just a horror.

Timing of care and delays in care seeking

Some participants mentioned avoiding care, only considering their clinicians as a last resort. Others delayed procedures that made them feel uncomfortable. Some delayed seeking care because they were fearful of receiving an unwanted diagnosis, while others understood the importance of early intervention. For some, accessing appropriate care was just part of their normal routine.

Theme 10: Avoiding health care until absolutely necessary

Some participants (n = 25) largely considered their clinicians as a last resort. Participants described watching and waiting and “working through it”—trying things on their own before going to the doctor. These participants tended to be concerned about bothering their clinicians with minor problems and did not see the utility of regular health assessments if they felt healthy. Participants downplayed what they perceived to be minor conditions and saw a clinician only when absolutely necessary. Some waited until it was almost an emergency.

I’m old school. I get pretty sick before I go to the doctor. I don’t go in just for anything. That is kind of a last resort and I think that’s the way I grew up; you self-medicate until you need drugs and then you go to the doctor. [Laughs.] That’s just the way I was brought up.

----------

Interviewer: What is it that keeps you from going?

Participant: That’s a good question. It’s probably a belief that most of those things that are somewhat minor to me will kind of work themselves out in a few days, or a week... If I can manage, I usually will just try to put up with it.

Theme 11: Delaying uncomfortable procedures and situations

Participants (n = 18) mentioned not necessarily being afraid to go visit their clinicians, but felt uncomfortable with the procedures they performed and delayed care in response. When patients felt comfortable, or were reassured about procedures in place to keep them comfortable, they were less hesitant to seek care.

You don’t want to go and sit on this paper-covered table and be measured, and everything. The whole experience is what I don’t really like. I don’t know how you could change it to make me enjoy it.

Theme 12: Fear and anxiety about conditions and diagnoses can present barriers or facilitate service seeking

Although nearly half of participants indicated that fear did not affect their health care visits (n = 68), a few were avoidant and fearful (n = 14) and described feeling that, if they had a life-altering disease, they preferred not knowing about it. This kept them from seeing clinicians. Other participants were fearful, but understood that they needed to see their clinicians in order to catch things early. For example:

There has never been a time when I thought I had a specific serious illness, but I think that’s part of getting a checkup in general. It’s that I’m afraid….I think that might be part of why I don’t go. I think it’s this fear that I might have leukemia or something like that. But also I think it’s important that you know those things. That is also one of the reasons that I do go.

Theme 13: Using health care services is just part of the normal routine

In contrast to people who were afraid that routine care and screenings would result in negative outcomes, some participants reported a “matter-of-fact” approach to visiting their clinicians (n = 35). For example, one participant reported that “I just have to go,” others that it is an item on their “to-do list.”

It’s part of my routine; I just do it. When the time comes around, it’s, “Oh, a year’s gone by so I’d better get out there and get one [physical] done.”

Conclusion

Enabling factors were commonly discussed themes in our qualitative data when it came to seeking preventive or routine services. Factors such as the time commitment required to attend visits, dislike of cumbersome processes (e.g., making appointments, filling prescriptions), and costs all presented barriers to accessing care, whereas welcoming staff and clinicians’ collaborative, caring, and respectful approaches facilitated care seeking. These findings are consistent with previous research suggesting that shorter waiting times, having a regular clinician as a primary care provider, and long-term continuity of care produce favorable patient-physician relationships.19–21;28;29 Thus, modifying the social and physical environments by addressing organizational factors, such as those that improve patient-clinician relationships (e.g., promoting continuity of care; facilitating clinician-patient communication) and streamlining processes (e.g., reducing waiting times), may reduce important barriers to use of preventive and other routine care. In these times of increasingly tight healthcare budgets, such efforts have the potential to improve patient flow in addition to patient satisfaction. However, the extent to which healthcare organizations can respond to recommendations such as these may be limited by resource constraints at the organizational and system levels. For example, need for primary care in this country exceeds the supply of available providers, and expanded care through the Affordable Care Act may worsen this scenario. Future research should seek to identify modifiable factors at the organizational and systems levels that might enhance capacity, improve processes, and facilitate implementation of quality and service improvement efforts.

Individuals’ attitudes also played an important role in our findings. Some people disliked doctors and seeking care, and avoided doing so until absolutely necessary. Those who avoided care until necessary often thought that problems would go away on their own and did not see the point of physical assessments if they felt healthy. Participants mentioned the importance of education to help people determine when “watchful waiting” was appropriate, when they needed to seek health care, and about the importance of preventive services, irrespective of health status. Such education will become increasingly important as health care coverage expands, if we are to ensure that people receive appropriate levels of care—neither too much nor too little. Again, system capacity constraints may restrict traditional patient education methods, new communication technologies, however, present novel opportunities for patient education. Discomfort, fear, and anxiety associated with preventive procedures, such as colonoscopies, also led to avoidance for some participants, while for or others, going to the doctor was just part of their normal routine. Some participants who were concerned about uncomfortable procedures indicated that they were more likely to follow through with them if they were reassured about the measures that would be taken to ensure their comfort. Thus, tailoring communications to address patients’ fears about procedures through education, reassurance, and by adopting methods that reduce discomfort, could increase some patients’ willingness to engage in uncomfortable or embarrassing screening procedures.

Limitations

Because the interview component of the project was exploratory in nature, the sample was selected to increase heterogeneity with regards to gender, service use and drinking patterns. Thus, a random sample of adult health plan members may have produced a different, likely narrower, range of responses. In addition, because themes were emergent (that is, we asked general questions and reported common themes among responses) the counts provided are likely undercounts of the numbers of individuals who might endorse these themes if they were to be asked directly about them. Other limitations include a mailed questionnaire-response rate that was lower than desired in the parent study and sampling from an insured population within a region of the US that is predominately white, thus results are not likely to be representative of non-insured, non-HMO, non-white populations. Given our sampling strategy, we did not intend to produce a representative sample. Rather, we intended to explore the perspectives of a range of men and women with different patterns of service seeking and different health-related practices (alcohol consumption). As such, this work should be seen as exploratory and hypothesis-generating and further research is needed with larger, representative samples to evaluate these findings. Lastly, although we collected these data a number of years ago, we believe that patient perspectives regarding the factors affecting their willingness and ability to seek care are unlikely to have changed substantially in the intervening years.

SO WHAT?

What is already known on this topic?

Few studies have used qualitative interview data to explore how health-related attitudes, beliefs, feelings, and health-related practices affect willingness to seek use of health care, particularly preventive services. Our findings suggest that addressing some of these barriers at the organizational- and patient-level could increase uptake of important preventive services.

What does this article add?

Participants were more willing to see their clinicians when they had a positive relationship with a caring and collaborative physician. In the context of such relationships, education about appropriate preventive care was seen as possible. Barriers included dislike of time commitment (particularly waiting times) and unwelcoming clinic environments. A small number of individuals also cited costs, which are likely a greater concern to individuals not insured through a HMO. Thus, reducing costs for preventive care as part of health care reform, and improving processes and clinic friendliness should increase uptake of preventive service use. Helping patients manage anxiety, concern and discomfort resulting from screening procedures such as mammograms and colonoscopies, could result in important increases in uptake of such services. Finally, we found that some people appear to avoid health care because of their health-related practices. Finding methods to make these people more comfortable seeking care will be a prerequisite to helping them make changes to their health behaviors.

What are the implications for health promotion practice or research?

To increase use of preventive services within routine care, health care systems should focus on delivering care in ways that allow patients and clinicians to develop strong, long-term relationships, in which clinicians can educate and collaborate with patients. Improving care-related processes to reduce time burden on patients and ensuring welcoming, friendly, and easy-to-navigate organizations may increase patients’ willingness to seek preventive and routine services. In the context of the expansions in preventive care expected from implementation of the Affordable Care Act,1 better understanding these patient-level factors, addressing barriers, and facilitating timely preventive services have the potential to improve community health.

Contributor Information

Carla A. Green, Email: carla.a.green@kpchr.org, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, 3800 N Interstate Avenue, Portland OR 97227, (503) 335-2479, (503) 335-2428.

Kim M. Johnson, Email: johnskim22@gmail.com, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, 3800 N Interstate Avenue, Portland OR 97227, (503) 886-9343, (503) 335-2428.

Bobbi Jo H. Yarborough, Email: bobbijo.h.yarborough@kpchr.org, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, 3800 N Interstate Avenue, Portland OR 97227, (503) 335-6325, (503) 335-6311.

References

- 1.Kocher R, Emanuel EJ, DeParle NA. The Affordable Care Act and the future of clinical medicine: the opportunities and challenges. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:536–539. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-8-201010190-00274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen RM, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Millbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 1973;51:95–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiscella K, Franks P, Clancy CM. Skepticism toward medical care and health care utilization. Med Care. 1998;36:180–189. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199802000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiscella K, Goodwin MA, Stange KC. Does patient educational level affect office visits to family physicians? J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(3):157–165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green CA, Polen MR. The health and health behaviors of people who do not drink alcohol. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:298–305. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00365-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armstrong MA, Midanik LT, Klatsky AL. Alcohol consumption and utilization of health services in a health maintenance organization. Med Care. 1998;36:1599–1605. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199811000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polen MR, Green CA, Perrin NA, Anderson BM, Weisner CM. Drinking patterns, gender and health I: Attitudes and health practices. Addict Res Theory. 2010;18:122–142. doi: 10.3109/16066350903398486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice C, Duncan DF. Alcohol use and reported physician visits in older adults. Preventive Medicine. 1995;24:229–234. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rice DP, Conell C, Weisner CM, Hunkeler EM, Fireman B, Hu TW. Alcohol drinking patterns and medical care use in an HMO setting. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2000;27:3–16. doi: 10.1007/BF02287800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Boer AG, Wijker W, de Haes HC. Predictors of health care utilization in the chronically ill: a review of the literature. Health Policy. 1997;42:101–115. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(97)00062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berki SE, Ashcraft ML. On the analysis of ambulatory utilization: An investigation of the roles of need, access and price as predictors of illness and preventive visits. Med Care. 1979;17:1163–1181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riley AW, Finney JW, Mellits ED, et al. Determinants of children’s health care use: An investigation of psychosocial factors. Med Care. 1993;31:767–783. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199309000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evashwick C, Rowe G, Diehr P, Branch L. Factors explaining the use of health care services by the elderly. Health Serv Res. 1984;19:357–382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vasiliadis HM, Tempier R, Lesage A, Kates N. General practice and mental health care: determinants of outpatient service use. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(7):468–476. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faulkner LA, Schauffler HH. The effect of health insurance coverage on the appropriate use of recommended clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 1997;13:453–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gold R, Devoe JE, McIntire PJ, Puro JE, Chauvie SL, Shah AR. Receipt of diabetes preventive care among safety net patients associated with differing levels of insurance coverage. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:42–49. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.01.110142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green CA, Polen MR, Leo MC, Perrin NA, Anderson BM, Weisner CM. Drinking patterns, gender and health II: Predictiors of preventive service use. Addict Res Theory. 2010;18:143–159. doi: 10.3109/16066350903398494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blewett LA, Johnson PJ, Lee B, Scal PB. When a usual source of care and usual provider matter: adult prevention and screening services. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1354–1360. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0659-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu KT. Usual source of care in preventive service use: a regular doctor versus a regular site. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1509–1529. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.10524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrante JM, Balasubramanian BA, Hudson SV, Crabtree BF. Principles of the patient-centered medical home and preventive services delivery. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:108–116. doi: 10.1370/afm.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parchman ML, Burge SK. The patient-physician relationship, primary care attributes, and preventive services. Fam Med. 2004;36(1):22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gunzerath L, Faden V, Zakhari S, Warren K. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism report on moderate drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:829–847. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128382.79375.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blankertz L. The value and practicality of deliberate sampling for heterogeneity: A critical multiplist perspective. American Journal of Evaluation. 1998;19:307–324. [Google Scholar]

- 25.User’s Manual for ATLAS.ti 6.0. Berlin: ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lofland J, Lofland LH. Analyzing social settings: a guide to qualitative observation and analysis. 3. New York: Wadsworth Publishing; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luborsky MR. In: The identification and analysis of themes and patterns. Gubrium J, Sankar A, editors. New York: Sage Publications; 1994. pp. 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green CA, Polen MR, Janoff SL, et al. Understanding how clinician-patient relationships and relational continuity of care affect recovery from serious mental illness: STARS study results. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008;32:9–22. doi: 10.2975/32.1.2008.9.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrante JM, Balasubramanian BA, Hudson SV, Crabtree BF. Principles of the patient-centered medical home and preventive services delivery. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:108–116. doi: 10.1370/afm.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]