Abstract

Background

Deqi is a central concept in traditional Chinese acupuncture. We performed a secondary analysis on data from a larger randomized controlled trial (RCT) in order to assess the effect of acupuncture on deqi traits and pain intensity in primary dysmenorrhea.

Methods

A total of 60 primary dysmenorrhea patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to one of three treatment groups. Acupuncture was given at SP6, GB39 or nonacupoint. Subjective pain was measured by a 100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS) before and after acupuncture. The Massachusetts General Hospital acupuncture sensation scales (MASS) with minor modification was used to rate deqi sensations during acupuncture.

Results

The results showed that VAS scores of pain after acupuncture were significantly decreased comparing to before acupuncture treatment in all three groups (P = 0.000). However, no significant differences were found among three groups at the beginning or end of acupuncture treatment (P = 0.928, P = 0.419).

Conclusions

There was no statistical difference among three groups in terms of intensity of deqi feeling. The types of sensation were similar across the groups with only minor differences among them.

Trial registration

Trial registration number: Controlled-Trials.com ISRCTN24863192.

Keywords: Acupuncture, Deqi traits, Pain intensity, Primary dysmenorrhea

Background

Acupuncture has been increasingly used as an alternative and complementary therapy in various clinical conditions, especially in the pain management [1-3]. But its mechanism is still unclear. According to both ancient traditional Chinese and modern text books, the deqi feeling of patients is different, which is referred as suan (aching or soreness), ma (numbness or tingling), zhang (fullness/distention or pressure) or zhong (heaviness) around the acupuncture point and/or along the meridians [4,5].

Recent controversy in the field of acupuncture research has been generated when several large scale RCTs showed no significant differences between acupuncture and minimal or sham acupuncture. But compared to control cases, the clinical effects of acupuncture treatment are significantly positive [6-8]. It claims that deqi is important in creating a positive clinical outcome [5,9]. Non-penetrative “placebo needles” such as the streitberger needle also elicited deqi, which presenting a problem when acupuncture is evaluated within controlled trials [10,11]. Thus, deqi may have implications both for clinical practice and trial design. Deqi traits mean the nature of the sensation and intensity. There is no consensus for a method or instrument to quantify deqi sensations. Particularly, few studies have investigated the effect of acupuncture on different aspects of deqi or pain relief [12,13]. We had previously designed AAEPD-II to investigate immediate effects of acupuncture at a specific acupoint compared with unrelated acupoint and nonacupoint among primary dysmenorrhea patients. The present data was a secondary analysis from the main RCT to assess the effect of acupuncture on different aspects of deqi and pain relief in primary dysmenorrhea.

Methods

Study design overview

The main study was designed as a multicentre RCT with a sample size of 501 in six large hospitals of China (i.e., Dongzhimen Hospital affiliated to Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine affiliated to Capital Medical University, Huguosi Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine affiliated to Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, the First Hospital affiliated to Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and the Hospital affiliated to Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine). We used the subset of the data for this paper only from one hospital (the First Hospital affiliated to Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine) with a total of 60 primary dysmenorrhea patients. That is, 23 patients in SP6 acupuncture group, 26 in GB39 control group and 11 in Nonacupoint control group, respectively. The methodology is the same with the main study [14].

The trial protocol has been approved by the Research Ethical Committee of the First Hospital affiliated to Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and the study itself was conducted according to common standard guidelines (Declaration of Helsinki, Good Epidemiological Practice: http://www.dundee.ac.uk/iea/GoodPract.htm). Written informed consent were obtained from participants or caregivers if children under the age of 18.

Outcomes

Demographic measures collected at the baseline evaluation included age, menstrual cycle and baseline pain intensity.

Pain intensity

This was measured on a standard of 100-mm VAS (0 = no pain, 100 = worst pain ever), before and after acupuncture. Mean pain scores were calculated for both pre- and post-acupuncture dysmenorrhea pain.

Deqi sensations

Deqi was monitored with the MASS [12]. Seven most common descriptors in Chinese, which were soreness, numbness, heaviness, warmth, cold, sharp pain and dull pain, were selected for minor modifications. Immediately after the needle was inserted into the skin, the subject was asked by another researcher if deqi sensations occurred during the stimulation. And the intensity was rated on the scale of 1–100 mm.

The “Acupuncture Sensation Spreading Scale” was also used to rate the localization and expansiveness of deqi sensations along the lower limbs [13]. Orienting marks on this separate continuum include “none”, “localized”, “ankle”, “upper legs”, “lower legs”, and “knee-joint”, ranging from 0 to 5 scores. Others surrounded kept quiet during the whole intervention until the questionnaire was assessed and filled in.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 13.0 for Windows statistical software was used in the statistical analysis. Mean ± Standard Error (Mean ± SE) was given for each parameter. One-way ANOVA or rank sum test were used to compare the between-group differences for quantitative data. Enumeration data were presented as frequency using chi-square test or Fisher exact probability test. The significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Demographic data of subjects

There were no significant differences at the baseline among three groups. On average, participants were at 22.4 ± 2.8 years of age and had experienced pain for about 83.2 ± 40.7 months. The average baseline score on the VAS was 64.8 ± 16.8 mm for pain intensity of dysmenorrhea.

Comparisons of pain intensity

Comparisons of the pain intensity before and immediately after acupuncture were presented in Table 1. Compared to pre-acupuncture, VAS scores in three groups were significantly decreased after acupuncture treatment (P = 0.000). However, the VAS scores showed no significant differences among three groups at the beginning of acupuncture (Pre-acu, P = 0.928). Meanwhile, no significant differences were detected among patients in three acupuncture groups after intervention (Post-acu, P = 0.419).

Table 1.

VAS scores of pain intensity pre- and post-acupuncture (mm, Mean ± SE)

| Group | N | Pre-acu | Post-acu | *P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP6 acupuncture group |

23 |

54.26 ± 2.312 |

31.96 ± 3.082 |

0.000 |

| GB39 control group |

26 |

55.42 ± 1.842 |

36.58 ± 3.358 |

0.000 |

| Nonacupoint control group |

11 |

55.09 ± 3.755 |

30.00 ± 4.143 |

0.000 |

| □P | 0.928 | 0.419 |

*P values are for within-group comparisons of the three groups.

□P values are for between-group comparisons of the three groups. VAS indicates visual analogue scale.

Ratings of Deqi sensations

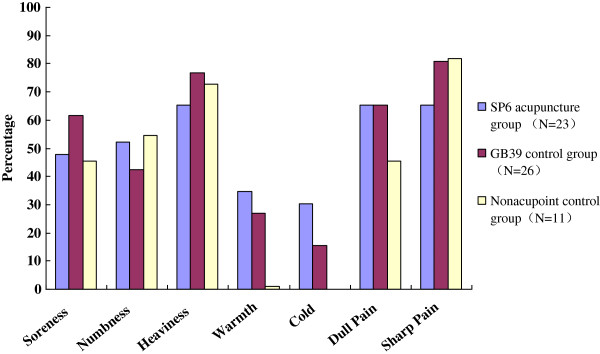

Type of needling sensations was recorded. And the proportion of patients with particular sensation was shown in Table 2. It should be noted that these data reflected the fact that the majority of patients recorded more than one sensation. In Table 3, there were no significant differences among the intensity of seven sensations.

Table 2.

Frequency of deqi sensations in the three groups

| Sensations |

SP6 acupuncture group |

GB39 control group |

Nonacupoint control group |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 23) | (N = 26) | (N = 11) | ||

| Soreness |

11 (47.83%) |

16 (61.54%) |

5 (45.45%) |

0.533 |

| Numbness |

12 (52.17%) |

11 (42.31%) |

6 (54.55%) |

0.710 |

| Heaviness |

15 (65.22%) |

20 (76.92%) |

8 (72.73%) |

0.660 |

| Warmth |

8 (34.78%) |

7 (26.92%) |

1 (0.90%) |

0.285 |

| Cold |

7 (30.43%) |

4 (15.38%) |

0 (0%) |

0.088 |

| Dull pain |

15 (65.22%) |

17 (65.38%) |

5 (45.45%) |

0.473 |

| Sharp pain | 15 (65.22%) | 21 (80.77%) | 9 (81.82%) | 0.385 |

Table 3.

Comparisons of the intensity of deqi sensations among the three groups (mm, Mean ± SE)

| Sensations |

SP6 acupuncture group |

GB39 control group |

Nonacupoint control group |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 23) | (N = 26) | (N = 11) | ||

| Soreness |

9.96 ± 2.95 |

12.46 ± 3.08 |

8.64 ± 3.82 |

0.701 |

| Numbness |

14.87 ± 4.35 |

8.04 ± 2.95 |

10.00 ± 4.52 |

0.392 |

| Heaviness |

24.57 ± 5.29 |

21.15 ± 3.66 |

22.73 ± 5.85 |

0.869 |

| Warmth |

7.17 ± 2.77 |

5.38 ± 2.25 |

4.55 ± 4.55 |

0.824 |

| Cold |

6.96 ± 3.40 |

1.50 ± 0.77 |

0.00 ± 0.00 |

0.105 |

| Dull pain |

19.13 ± 4.11 |

15.12 ± 3.18 |

12.27 ± 5.93 |

0.554 |

| Sharp pain | 27.72 ± 4.91 | 23.46 ± 4.51 | 25.00 ± 7.69 | 0.822 |

Every sensation demonstrated some virtual differences in frequency of experience among three groups. Many sensations were shared by the deqi response generated at SP6, GB39 and nonacupoint. But more careful examination of the data revealed differences in frequency and intensity of individual sensations. Sharp pain, heaviness and dull pain were the most frequent sensation in SP6 acupuncture group and GB39 control group. However, followed by sharp pain and heaviness, numbness is another sensation occurred in the nonacupoint control group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of various needling sensations in the three groups. 100% indicates that the individual sensation occurs in all subjects.

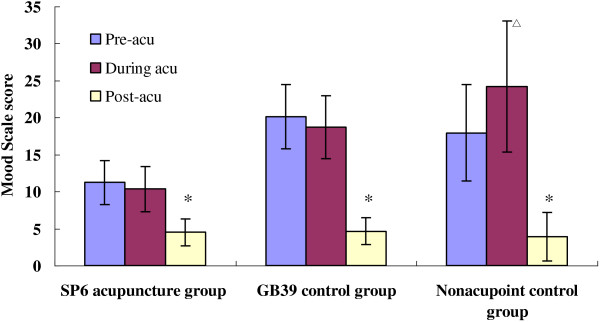

In Figure 2, it showed that patients receiving acupuncture at SP6 tended to relieve the pain intensity easier than those receiving acupuncture at GB39 or nonacupoint. In addition, most deqi sensations expensed to the “upper legs” and “lower legs” along the lower limbs.

Figure 2.

Comparison of anxiety among three groups. △ Compared with pre-acu P<0.05. * Compared with pre-acu P<0.05.

Discussion

This secondary analysis of data aimed to assess acupuncture needling sensations and the therapeutic effect of acupuncture. The results showed that pain relief occurred after acupuncture treatment in primary dysmenorrhea patients. But there exist no significant differences among three groups in terms of intensity of deqi feeling.

Deqi is a central concept in traditional Chinese acupuncture [2,15]. Many investigators have attempted to assess the relationship between deqi and therapeutic effects [16,17]. Some found better pain relief for acupuncture with deqi[18,19], whereas others did not [20,21]. This result was similar to the results of White P et al., who suggested that the presence and intensity of deqi had no effect on pain relief for osteoarthritis (OA) patients [17].

Deqi is comprised of the sensation of the patient and the sensation of the acupuncturist [22]. Patients experienced deqi as multiple unique sensations at the needle site and surrounding regions [23]. Meanwhile, the perception of acupuncturist has been described as a slight pull of the needle downwards into the tissue [4,24,25]. It was recommended that the study should have frequent recording of deqi, using a much more sensitive measure and also be prudent to record any deqi noted by acupuncturists.

Deqi is difficult to study because of its subjective nature and multifactor influence. Factors such as patient’s body constitution, severity of the illness, acupoint location, needling techniques, manipulation skills of the acupuncturist, competence and understanding of the TCM theory, also play an important role in the therapeutic outcome [6].

Although this is not supported by current study that deqi is stronger at acupoints than at nonacupoints [26], sharp pain, heaviness and dull pain are the most frequent sensations in SP6 acupuncture group and GB39 control group. However, it was noted that numbness sensation occurred more often during acupuncture at nonacupoint, whereas the frequency of sharp pain and heaviness was similar to acupoints. Heaviness, aching, soreness, warmness and dull pain are conveyed by the slower-conducting Ad and C fibers, whereas numbness is conveyed by the faster-conducting Ab fibers [27]. Acupuncture at SP6 tended to relieve the pain intensity easier in primary dysmenorrhea patients than those receiving acupuncture at GB39 or nonacupoint.

An appropriate method of measuring deqi needs to be developed to support further acupuncture investigation. Researchers have sought to establish a credible rating scale for deqi, such as the Subjective Acupuncture Sensation Scale (SASS) [28,29], the MASS [13], the Southampton Needle Sensation Questionnaire [16] and the “deqi composite” [30]. In past decades, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) had been used to qualitatively and quantitatively characterize deqi sensations[31]. An fMRI study found strong deqi sensations induced strong deactivation of the limbic system [32]. Hui et al. found deqi response of acupoint stimulation likely arises from A-delta and C-fiber stimulation by the needle [30].

There are several limitations in this study. The decision of an appropriate control procedure for clinical studies on acupuncture is a particular challenge [7]. Previous acupuncture RCTs suggested that needling of acupoints was as effective as nonacupoints, in particular for pain relief, although both interventions were more effective than a waiting list control [21,33,34]. Few guidelines exist, however, for identifying appropriate sham point locations; the depth, direction, and duration of needle insertion; or the need for needle stimulation. Inserting a needle into any location is likely to have a physiological effect through a variety of mechanisms. It is still unknown what the sphere of influence is for local acupoints. For example, the distance of a point away from the needle-inserted acupoint that will not be also stimulated. Electrical stimulation was added after the initial deqi sensations was elicited for dysmenorrhea pain relief. Electro-acupuncture tends to elicit a strong “tingling” sensation which can easily mask pure deqi sensations. Besides, this is a secondary analysis of data from a RCT, which has a relatively big sample size and a statistical analysis in detail. However, in this paper, sample size is relatively small.

A power calculation was presented based on post hoc power analysis. This secondary data analysis was with a power of 25.44%. So this study may be underpowered to detect any differences. Possible reasons include that deqi is difficult to study because of its subjective nature and multifactor influence. Factors such as patient’s body constitution, severity of the illness, acupoint location, needling techniques, manipulation skills of the acupuncturist, competence and understanding of TCM theory, play important roles in the therapeutic outcome. Beside, patients experience deqi as multiple unique sensations at the needle site and surrounding regions. Multiple sensations usually present at the same time. It is underpowered to detect any differences for one single deqi sensations.

Due to the short term therapy and subjectivity of patients when rating the VAS scales, we found that the intensity of deqi during treatment does not relate to treatment outcome for primary dysmenorrhea pain. There are slight, but not clinical, differences in the most frequent sensations between acupoints and nonacupoints.

Conclusions

There were no statistical differences among three groups in terms of intensity of deqi feeling. The types of sensation were similar across the groups with only minor differences among them. There existed no enough evidence for the role of deqi in acupuncture treatment. An appropriate method of measuring deqi needs to be developed to support further acupuncture investigation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

G-XS wrote and revised the manuscript, C-ZL and L-PW developed the original concepts for the review, Q-QLi, L-PG and M-MW have made substantial contributions to acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data; L-LH wrote the first draft of the paper. JW revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the paper during development and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Guang-Xia Shi, Email: shiguangxia2008@126.com.

Qian-Qian Li, Email: li1986qian@126.com.

Cun-Zhi Liu, Email: lcz623780@126.com.

Jiang Zhu, Email: jzhjzh@263.net.

Lin-Peng Wang, Email: 741503673@qq.com.

Jing Wang, Email: princrystal@sina.com.

Li-Li Han, Email: 734399206@qq.com.

Li-Ping Guan, Email: houqinbuzhangsgx@163.com.

Meng-Meng Wu, Email: gaoma777@163.com.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, reference number: 2012CB518506 and 2006CB504503).

References

- Linde K, Witt CM, Streng A, Weidenhammer W, Wagenpfeil S, Brinkhaus B, Willich SN, Melchart D. The impact of patient expectations on outcomes in four randomized controlled trials of acupuncture in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2007;128(3):264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaptchuk TJ. Acupuncture: theory, efficacy, and practice. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(5):374–383. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Eisenberg DM, Erro J, Hrbek A, Deyo RA. The practice of acupuncture: who are the providers and what do they do? Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(2):151–158. doi: 10.1370/afm.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XN. Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion. Beijing: Foreign Language Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson H, Asghar A. Acupuncture needle sensations associated with deqi: a classification based on experts’ ratings. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12(7):633–637. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkhaus B, Witt CM, Jena S, Linde K, Streng A, Wagenpfeil S, Irnich D, Walther HU, Melchart D, Willich SN. Acupuncture in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(4):450–457. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde K, Streng A, Jurgens S, Hoppe A, Brinkhaus B, Witt C, Wagenpfeil S, Pfaffenrath V, Hammes MG, Weidenhammer W, Willich SN, Melchart D. Acupuncture for patients with migraine: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2118–2125. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.17.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener HC, Kronfeld K, Boewing G, Lungenhausen M, Maier C, Molsberger A, Tegenthoff M, Trampisch HJ, Zenz M, Meinert R. GERAC Migraine Study Group. Efficacy of acupuncture for the prophylaxis of migraine, a multicentre randomized controlled clinical trial. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:310–316. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao JJ, Farrar JT, Armstrong K, Donahue A, Ngo J, Bowman MA. De qi: Chinese acupuncture patients’ experiences and beliefs regarding acupuncture needling sensation–an exploratory survey. Acupunct Med. 2007;25(4):158–165. doi: 10.1136/aim.25.4.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Bang H, Kim Y, Park J, Lee S, Lee H, Park HJ. Non-penetrating sham needle, is it an adequate sham control in acupuncture research? Complement Ther Med. 2011;19(Suppl 1):S41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, White A, Stevinson C, Ernst E, James M. Validating a new non-penetrating sham acupuncture device: two randomized controlled trials. Acupunct Med. 2002;20(4):168–174. doi: 10.1136/aim.20.4.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, Gollub R, Huang T, Polich G, Napadow V, Hui K, Vangel M, Rosen B, Kaptchuk TJ. Acupuncture de qi, from qualitative history to quantitative measurement. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(10):1059–1070. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A, Cummings M, Barlas P, Cardini F, Filshie J, Foster NE, Lundeberg T, Stener-Victorin E, Witt C. Defining an adequate dose of acupuncture using a neurophysiological approach–a narrative review of the literature. Acupunct Med. 2008;26(2):111–120. doi: 10.1136/aim.26.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YQ, Ma LX, Xing JM, Cao HJ, Wang YX, Tang L, Li M, Wang Y, Liang Y, Pu LY, Yu XM, Guo LZ, Jin JL, Wang Z, Ju HM, Jiang YM, Liu JJ, Yuan HW, Li CH, Zhang P, She YF, Liu JP, Zhu J. Does Traditional Chinese Medicine pattern affect acupoint specific effect? Analysis of data from a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial for primary dysmenorrhea. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19(1):43–49. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asghar AU, Green G, Lythgoe MF, Lewith G, MacPherson H. Acupuncture needling sensation: the neural correlates of Deqi using fMRI. Brain Res. 2010;1315:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, Fufa DT, Gerber AJ, Rosman IS, Vangel MG, Gracely RH, Gollub RL. Psychophysical outcomes from a randomized pilot study of manual, electro, and sham acupuncture treatment on experimentally induced thermal pain. J Pain. 2005;6(1):55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White P, Prescott P, Lewith G. Does needling sensation (de qi) affect treatment outcome in pain? Analysis of data from a larger single-blind randomized controlled trial. Acupunct Med. 2010;28(3):120–125. doi: 10.1136/aim.2009.001768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vas J, Perea-Milla E, Méndez C, Sánchez Navarro C, León Rubio JM, Brioso M, García Obrero I. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for chronic uncomplicated neck pain: a randomized controlled study. Pain. 2006;126(1–3):245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt C, Brinkhaus B, Jena S, Linde K, Streng A, Wagenpfeil S, Hummelsberger J, Walther HU, Melchart D, Willich SN. Acupuncture in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9480):136–143. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66871-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf HP, Mansmann U, Streitberger K, Witte S, Krämer J, Maier C, Trampisch HJ, Victor N. Acupuncture and knee osteoarthritis: a three-armed randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(1):12–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haake M, Müller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, Basler HD, Schäfer H, Maier C, Endres HG, Trampisch HJ, Molsberger A. German Acupuncture Trials (GERAC) for chronic low back pain: randomized, multicenter, blinded, parallel-group trial with 3 groups. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(17):1892–1898. doi: 10.1001/Archinte.167.17.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang FR. Acupuncture (Zhen Jiu Xue) Beijing: China Traditional Chinese Medicine Publishing; 2005. p. 195. [Google Scholar]

- Park H, Park J, Lee H, Lee H. Does Deqi (needle sensation) exist? Am J Chin Med. 2002;30(1):45–50. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X02000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enblom A, Hammar M, Steineck G, Börjeson S. Can individuals identify if needling was performed with an acupuncture needle or a non-penetrating sham needle? Complement Ther Med. 2008;16(5):288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langevin HM, Churchill DL, Wu J, Badger GJ, Yandow JA, Fox JR, Krag MH. Evidence of connective tissue involvement in acupuncture. FASEB J. 2002;16(8):872–874. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0925fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langevin HM, Churchill DL, Fox JR, Badger GJ, Garra BS, Krag MH. Biomechanical response to acupuncture needling in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91(6):2471–2478. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.6.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Wang P. Experimental Acupuncture. Shanghai: Shanghai Scientific and Technology Publishing House; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, Gollub RL, Webb JM, Kong JT, Vangel MG, Kwong K. Test-retest study of fMRI signal change evoked by electroacupuncture stimulation. Neuroimage. 2007;34(3):1171–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White P, Bishop F, Hardy H, Abdollahian S, White A, Park J, Kaptchuk TJ, Lewith GT. Southampton needle sensation questionnaire: development and validation of a measure to gauge acupuncture needle sensation. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(4):373–379. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui KK, Nixon EE, Vangel MG, Liu J, Marina O, Napadow V, Hodge SM, Rosen BR, Makris N, Kennedy DN. Characterization of the “deqi” response in acupuncture. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:33. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui KK, Liu J, Marina O, Napadow V, Haselgrove C, Kwong KK, Kennedy DN, Makris N. The integrated response of the human cerebro-cerebellar and limbic systems to acupuncture stimulation at ST 36 as evidenced by fMRI. Neuroimage. 2005;27(3):479–496. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui KK, Marina O, Claunch JD, Nixon EE, Fang J, Liu J, Li M, Napadow V, Vangel M, Makris N, Chan ST, Kwong KK, Rosen BR. Acupuncture mobilizes the brain’s default mode and its anti-correlated network in healthy subjects. Brain Res. 2009;1287:84–103. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.06.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch S. Clinical research on acupuncture (Part 2). Controlled clinical trials, an overview of their methods. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10:481–498. doi: 10.1089/1075553041323911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Almazor ME, Looney C, Liu Y, Cox V, Pietz K, Marcus DM, Street RL Jr. A randomized controlled trial of acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee: effects of patient-provider communication. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:1229–1236. doi: 10.1002/acr.20225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]