Abstract

We studied the photocatalytic properties of rational designed TiO2-ZnO hybrid nanostructures, which were fabricated by the site-specific deposition of amorphous TiO2 on the tips of ZnO nanorods. Compared with the pure components of ZnO nanorods and amorphous TiO2 nanoparticles, these TiO2-ZnO hybrid nanostructures demonstrated a higher catalytic activity. The strong green emission quenching observed from photoluminescence of TiO2-ZnO hybrid nanostructures implied an enhanced charge transfer/separation process resulting from the novel type II heterostructures with fine interfaces. The catalytic performance of annealing products with different TiO2 phase varied with the annealing temperatures. This is attributed to the combinational changes in Eg of the TiO2 phase, the specific surface area and the quantity of surface hydroxyl groups.

Semiconductor nanostructured composites draw intensive interests because of their improved properties and promising technological applications, such as photochemical solar cells, photo catalysts, photosensors, electro-luminescent displays, and biolabels. In recent years, considerable effort has been exerted toward combining semiconductor nanostructures with suitable materials to synergize their properties. For example, the deposition of metals or metallic islands on ZnO and TiO2 nanostructures can result in an enhanced photocatalytic performance1,2,3,4. Generally, photocatalytic efficiency is limited by a fast recombination of photogenerated charge carriers. In semiconductor/metal nanocomposites, the metal component can trap the photo-induced charge carriers and consequently promotes the interfacial charge-transfer processes1. Compared to the single element of ZnO and TiO2, coupled ZnO/TiO2 composite displays a largely improved photocatalytic activity, such as in the degradation of phenol, 2-chlorophenol, and pentachlorophenol5 and in the decomposition of salicylic acid6. This enhanced photocatalytic behavior is attributed to the efficient spatial separation of electrons and holes7. However, previous research works mainly studied the coupled ZnO/TiO2 with a simple core-shell structure (coated surface) or sandwich geometry (randomly adhered particles). Inappropriate structures of the interface in these two structures limit the interfacial charge-transfer process of photogenerated charge carriers and thus lower the photocatalytic property of the nanocomposite materials8,9,10,11. As such, challenges still remain in fabricating these nanohybrids with desirable interfacial structures. We have recently developed a simple method to build TiO2-ZnO (TZO) nanohybrid structures by a site-specific deposition of titanium oxide on ZnO nanorods (NRs)12. The TZO nanohybrids show uniform and atomically flat interfaces between ZnO and TiO2 with tunable crystal phases, which are amorphous, anatase and rutile. These TZO nanohybrid structures are expected to demonstrate an enhanced photocatalytic behavior. This is due to the improved interfacial structures which suit better the charge-transfer and spatial separation processes of photogenerated charge carriers. In this paper, we study the photocatalytic behaviors of TZO products and their annealed products with different TiO2 phase structures. The aim is to elucidate the relationship between various TZO structures and their photocatalytic properties.

Results

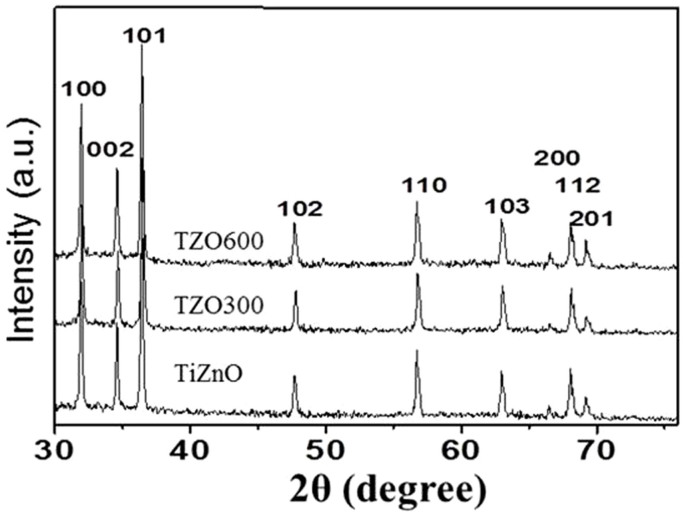

Figure 1 shows the XRD patterns of the produced TZO and the annealed TZOs, TZO300 and TZO600. The presence of Wurtzite-type hexagonal-phase ZnO is clearly shown in all samples with the lattice parameters a = 3.252Å and c = 5.208 Å. These data are in good agreement with the calculated values a = 3.253 and c = 5.209 (JCPDS 80-0075). There are no apparent peaks for anatase and rutile TiO2 in the XRD patterns of the annealed products. As the quantity of TiO2 coupled with ZnO NRs is very small, less than ~5 wt%, the XRD cannot detect them in the annealed substances.

Figure 1. XRD patterns of TZO, TZO300 and TZO600.

The prominent sharp peaks in all products are attributed to Wurtzite ZnO.

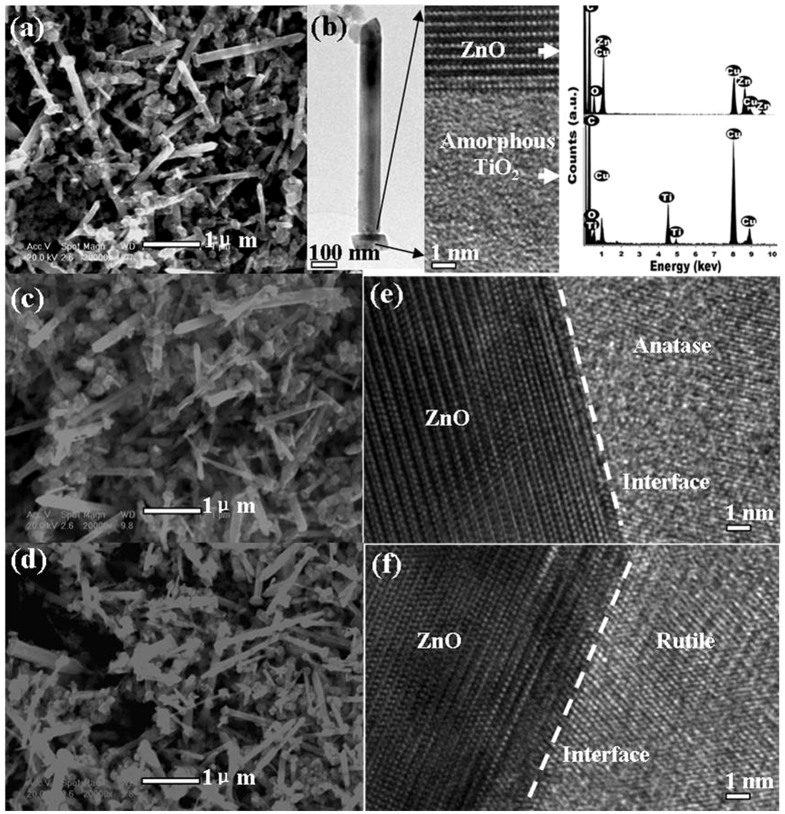

The scanning electron microscopy images of TZO products in Fig. 2a reveal that TiO2 NPs with diameters in the range of 20–250 nm are deposited on one of the frontier ends of ZnO NRs. These ZnO NRs have diameters in the range of 10–200 nm and lengths in the range of 1–3 μm. Fig. 2 shows that the typical morphology of a single TZO nanohybrid containing a cap-like TiO2 NP which covers one end of the ZnO NR. The ZnO NRs are well crystallized with no detected impurities in the EDX results. The titanium oxide particles assembled with NRs are identified as amorphous, and the stoichiometric ratio of Ti to O is approximately 1:2 as measured by EDS (see Fig. 2b). The interfaces between ZnO NRs and TiO2 are flat and clearly visible when the electron beam is perpendicular to the NRs axes. After annealing, the products are still well dispersed and the morphologies do not change (Fig. 2c and d) while the amorphous TiO2 caps have transformed to the anatase and rutile phases. The interface structures of almost all of the nanohybrids are similar and atomically flat. Readers can refer to our previous work12,13 for more details about the formation mechanism of TZO and related structural characterizations.

Figure 2.

(a) SEM image of TZO, (b) TEM and HRTEM images of a TZO and its EDS spectra, (c) and (d) SEM images of TZO300 and TZO600, (e) and (f) HRTEM images of TZO300 and TZO600, displaying the fine structures of the interface.

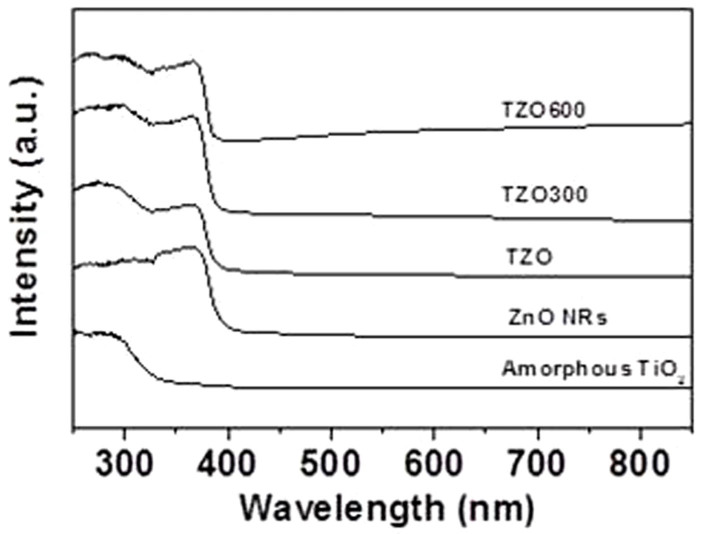

The UV-Vis absorption spectra of amorphous TiO2 NPs, ZnO NRs, TZO nanohybrids and the annealed products at 300°C (TZO300) and 600°C (TZO600) are compared in Fig. 3. ZnO NRs and all TZOs have strong adsorption in the UV region at the absorption edge of ca. 380 nm, with a corresponding ZnO bandgap of 3.26 eV. The amorphous TiO2 NPs have a strong adsorption in the deep-UV region at the absorption edge ca. 313 nm with a corresponding bandgap of 3.96 eV14,15. For TZO, a higher absorbance below 320 nm ensures that the TiO2 NPs, which are attached to ZnO NRs, dominate the deep UV absorption. This may enhance the use of UV light compared with pure ZnO NRs.

Figure 3. UV-Vis absorption spectra of amorphous TiO2 NPs, ZnO NRs, TZO nanohybrids and the annealed products TZO300 and TZO600.

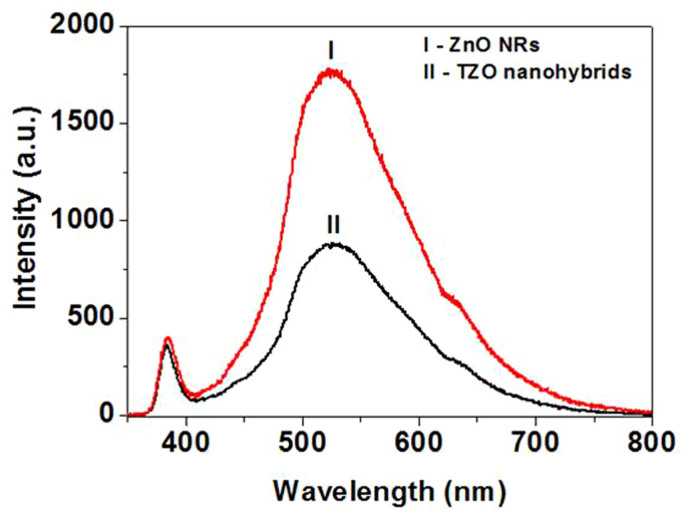

Other studies on semiconductor-semiconductor and semiconductor-metal composites such as CdS-ZnO16, CdS-SWCNT17, ZnO-SWCNT18, CdS-AgI19, CdS-TiO220, TiO2-Au21,22, and ZnO-Au23,24 have shown a charge equilibration when they are subjected to a bandgap excitation. Photo-induced electron transfer between composites can be initiated by the examined emission quenching (as shown in references 16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24). ZnO NRs with a bandgap of 3.26 eV undergo charge separation under UV-excitation (λ < 380 nm). These charge carriers (eCB and hVB) can be either directly recombined or trapped in the vacancies (et and ht)18. Research has shown that the green emission from ZnO colloids originates from oxygen vacancies25. The green emission with a maximum of ~525 nm is a useful probe to monitor the charge transfer process on the ZnO surface. In the present study we monitor the green emission from ZnO to investigate the charge transfer interaction with TiO2. Fig. 4 shows the PL spectra of ZnO NRs and TZO nanohybrids. Due to the site-specific assembly of TiO2 NPs on ZnO NRs with fine interfaces, ZnO NRs are expected to intensely interact with the deposited TiO2, and as a result of this interaction we expect a decrease in the emission yield of ZnO. Indeed, due to this interaction, a significant decrease, ~ca. 50%, in the emission yield of the TZO nanohybrids is observed compared with that of pure ZnO NRs as shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4. PL spectra of (I) ZnO NRs and (II) TZO nanohybrids.

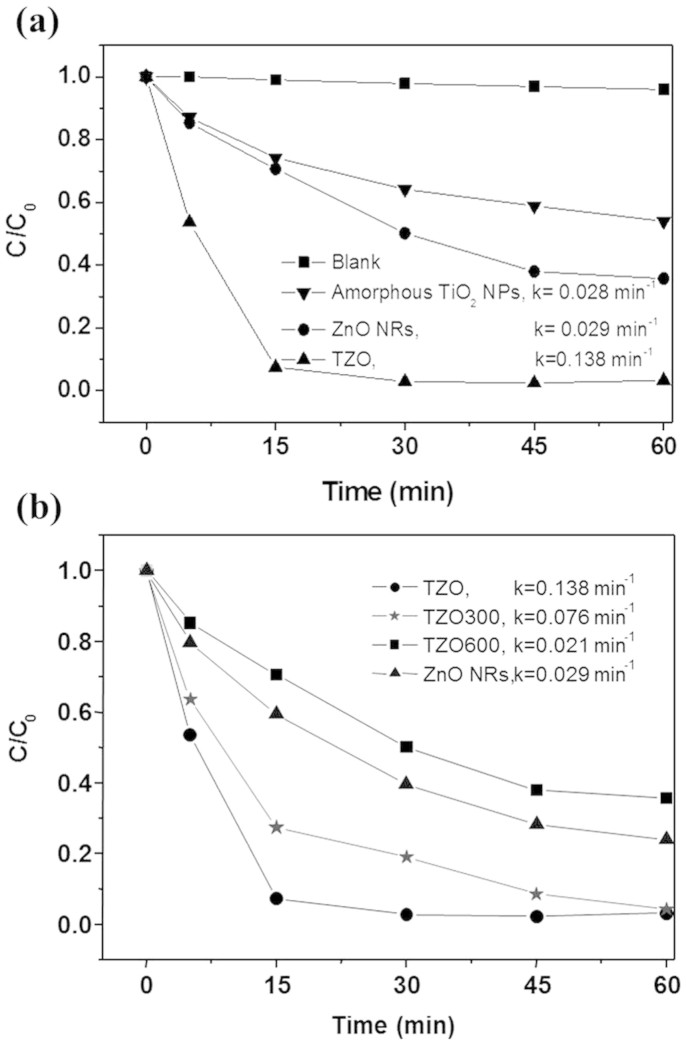

Now, to evaluate the photo-oxidation capability of TZO nanohybrids, we examine the decomposition of MB dye in solution over the samples TZO, TZO300, and TZO600 under UV light irradiation as a function of time (Fig. 5). For comparison, we carried out the decomposition of the MB dye in a solution over two reference photocatalysts, amorphous TiO2 NPs and ZnO NRs under UV light irradiation (Fig. 5a). To show that the decomposition of MB dye over TZO is caused neither by catalysis nor photolysis, we carried out a decomposition experiment in a dark environment with TZO as well as under a full arc light irradiation (with no catalyst, blank experiment in Fig. 5a). In these experiments, the MB concentration remained unchanged as a function of time, that is, TZO is an active catalyst under UV light. From an exponential decay at the initial stage (0~15 min), the decomposition kinetics follows a first order kinetics with the classical equation ln(C/C0) = −k·t, where k is the so-called pseudo-first rate kinetic constant, C0 is the initial concentration and C is the concentration after the MB degradation for time t. The presented k values in Fig. 5 are from fitting curves of the data for a 0–15 min period. These values represent a good measurement of the overall photo-degradation rate of all the investigated structures. TZO, with k = 0.138 min−1 which is about five times that of ZnO NRs, has the fastest MB decomposition rate. The photocatalytic activities of annealed products TZO300 and TZO600 decrease when the annealing temperature increases with the TiO2 phase on the TZO nanohybrid structures transformed from the amorphous to anatase and rutile phases.

Figure 5.

(a) Photodegradation of MB by amorphous TZO products, ZnO NRs, amorphous TiO2 NPs and blank experiment. (b) A comparison of the photocatalytic properties of ZnO NRs, TZO, TZO300 and TZO600.

Discussion

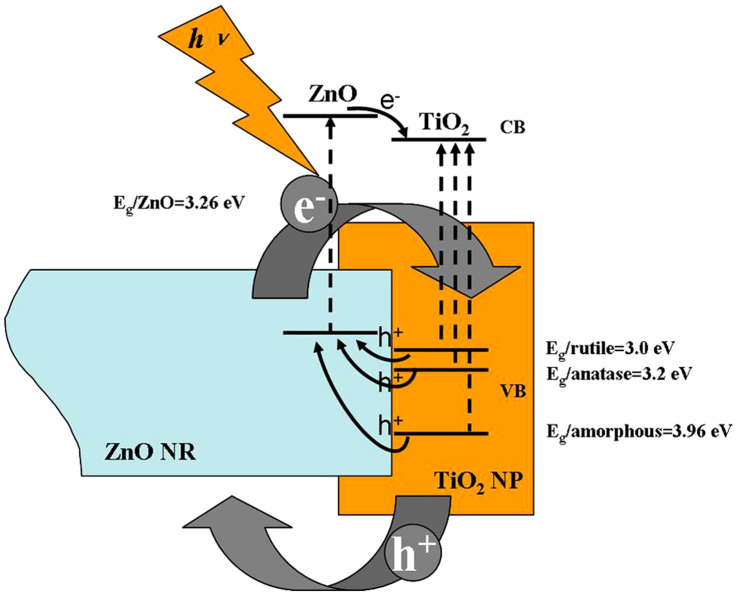

The TZO nanohybrids form a type II semiconductor heterostructure26 as shown in Fig. 6. In this case, electrons and holes in semiconductors are at their lowest energy states. Therefore, the energy gradient at the interfaces tends to spatially separate those electrons and holes which are excited by UV light on different sides of the hetero-junction. Under illumination, the electrons are transferred from the conduction band (CB) of ZnO to CB of TiO2. In addition, the holes are transferred from the valence band (VB) of TiO2 to VB of ZnO. This process isolates active electrons and holes and, hence, accelerates the decrease in the electron-hole pair recombination and erodes the increase in lifespan. These phenomena directly result in an intense emission quenching as revealed by the PL results in Fig. 4. They also increase the availability of the pairs (electron and hole) on the surface of the photocatalysts and thus enhance the redox process. Significantly, the fine atomic flat interfaces across TiO2 and ZnO of TZO nanohybrids ease this charge transfer/isolation process by a decreased interface resistance. In addition, the elongated one dimensional structure of ZnO nanorods also helps to decrease the recombination probability of photogenerated carriers due to an increased delocalization of electrons27. Therefore, our special TZO structures favor the photocatalytic process not only by the band structure configurations but also by the fine interface structures and geometrical structures between the two components TiO2 and ZnO.

Figure 6. Illustration of photo-induced charge transfer and separation at the interface of TZO heterostructures.

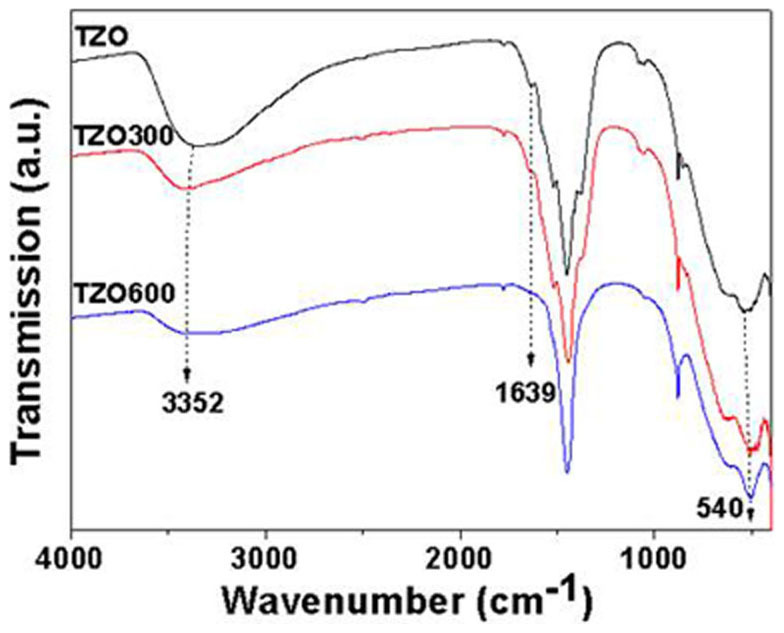

It is worthwhile to explain the rationale for the degeneration of the TZOs photocatalytic property sourced from the annealing treatment. First, as shown in Fig. 6, a larger energy gradient between VBZnO and VBTiO2 is apparently more beneficial for the transfer of active holes from TiO2 to ZnO. This difference is reduced as the bandgap energy (Eg) of TiO2 structures drops after annealing treatments (Eg/rutile (3.0 eV) < Eg/anatase (3.2 eV) <Eg/amorphous (3.96 eV)). Hence, the ability of the charge transfer/separation is consequently weakened. Second, specific surface area and surface hydroxyl groups can strongly affect photocatalytic activities of nanomaterials and, sometimes, they are the dominating factors compared with the crystal structure28. In the present case, an increase in annealing temperature results in a decrease in the specific surface area of TZOs (TZO 14.643 m2/g; TZO300 13.763 m2/g; TZO600 8.418 m2/g). This temperature variation also decreases the quantity of the surface of hydroxyl groups (See caption of Fig. 7) which slows the photocatalytic activities. Nevertheless, the reaction rates of annealed TZOs are relatively higher than or close to that for ZnO NRs. These rationales determine the enhanced photocatalytic activities of TZOs.

Figure 7. FTIR spectra of as-synthesized TZO, TZO300 and TZO600 samples in the wavenumber range of 4000–400 cm−1.

The broad absorptions at about 3352 and 1639 cm−1 are assigned to the hydroxyl groups of chemisorbed and/or physisorbed H2O molecules on the samples. A strong absorption band near 540 cm−1 reveals the vibration properties of ZnO NRs. Other unsigned peaks are attributed to remnant organic species in the samples.

In conclusion, this paper investigates the photocatalytic properties of TZOs and their annealed products with different TiO2 phases. Compared with the components of ZnO NRs and amorphous TiO2 NPs, the combined TZOs demonstrated higher catalytic activities. This is explained by an enhanced charge transfer/separation process resulting from the novel type II heterostructures with fine interfaces, and supported by the emission quenching mechanism in the PL studies. The catalytic performance of annealing products varied with the annealing temperatures. This originated from the combinational changes in Eg of the TiO2 phase, the specific surface area and the quantity of surface hydroxyl groups. Our investigation suggests an effective type of hybrid nanostructures for photocatalytic applications and other applications such as photodetectors and solar cells.

Methods

The method for the fabrication of TZO nanohybrid structures is similar to that described in our recent work12 and consists of three steps: 1) Preparation of ZnO NRs: 5 mL of 0.1 M zinc acetate ethanol solution was mixed with 35 mL of 0.5 M NaOH ethanol solution to form a suspension solution. The suspension solution was later transferred to a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave and kept at 180°C for 24 hours. 2) Preparation of sodium titanate nanotubes: 1 g of anatase TiO2 NPs were treated with a NaOH (10 M) aqueous solution in a Teflon vessel at 150°C for 12 hours29. 3) 200 mg sodium titanate nanotubes are mixed with the final reacted solution from step 1 and kept at 180°C for another 24 hours. Off-white precipitation products, obtained at the bottom of the autoclave, were sonicated for 30 minutes and then allowed to stand for another 30 minutes in order to separate them into two layers. The upper white TZO and the lower off-white superfluous amorphous TiO2 NPs were collected separately and washed with ethanol and DI water, centrifuged and dried at 80°C. The annealed TZOs were also prepared by heating the as-prepared TZO at 300°C (TZO300) and 600°C (TZO600) for 2 hours in air to convert the amorphous TiO2 NPs to the anatase and rutile phase, respectively. The crystallization of as-prepared samples was characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Philips, PW1813). Morphology and structure characterizations were carried out using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Philips XL-30) and a high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM, JEOL 2010F) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS). The photoluminescence (PL) was measured by a 325 nm He-Cd laser as the exciting light source. UV-Vis absorption spectrum measurement was conducted using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Lambda 20) and an integrating sphere (Labsphere) with a sampling spot of 10 mm × 10 mm at normal incidence. The surface area was characterized using a Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) machine and a surface-pore size analyzer (Beckman Coulter, SA 3100). Chemical bonding information of the samples was obtained using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR; Bio-Rad, FTS 600). For the photocatalytic measurement, 80 mg of each catalyst was suspended in 200 mL of a methylene blue (MB) aqueous solution (20 ppm). The mixture was poured into a quartz tube and kept in a dark environment for 30 minutes to allow it to attain an equilibrium adsorption state. The concentration of the MB solution slightly decreased while it was in the dark room with the C0 value slightly lower than 20 ppm at t = 0. UV irradiation was carried out using a 500 W high-pressure Hg lamp (with the strongest emission at 368 nm) and cooling by cycling water. After a set irradiation time, ~3 mL of the mixture was withdrawn, and the catalysts were separated from the suspensions by a centrifuge. The degradation process was monitored by the UV-Vis spectrophotometer measuring the absorption of MB at 664 nm.

Author Contributions

C.C. designed the research, performed TEM characterizations, and photocatalytic experiments, analysed the results and wrote the paper. A.A. and Z.X. performed the XRD and UV-Vis spectrophotometer characterization and the paper revision. C.Z. performed the nanomaterial fabrication. H.S. incorporated in the interpretation of experimental results. N.W. contributed significant discussion and final paper polishing.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Hong Kong Research Grants Council through RGC projects (No. FSGRF12SC22 and WMINST11SC04) and starting grants from South University of Science and Technology of China are gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Sheng F. et al. Simulation on field enhanced electron transfer between the interface of ZnO–Ag nanocomposite. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 18627–18633 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Gu C. D. et al. Growth and photocatalytic activity of dendrite-like ZnO@Ag heterostructure nanocrystals Cryst. Growth Des. 9, 3278–3285 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Han Y. et al. TiO2 supported Pd@Ag as highly selective catalysts for hydrogenation of acetylene in excess ethylene Chem. Commun. 49, 8350–8352 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y. H. et al. Ag/ZnO heterostructure nanocrystals: synthesis, characterization, and photocatalysis. Inorg. Chem. 46, 6980–6986 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpone N., Maruthamuthu P., Pichat P., Pelizzetti E. & Hidaka H. Exploiting the interparticle electron transfer process in the photocatalysed oxidation of phenol, 2-chlorophenol and pentachlorophenol: chemical evidence for electron and hole transfer between coupled semiconductors. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 85, 247–255 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Sukharev V. & Kershaw R. Concerning the role of oxygen in photocatalytic decomposition of salicylic acid in water. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 98, 165–169 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Marci G. et al. Preparation characterization and photocatalytic activity of polycrystalline ZnO/TiO2 systems.2 surface, bulk characteriza-tion, and 4-nitrophenol photodegradation in liquid-solid regime. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 1033–1040 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Chueh Y. L., Chou L. J. & Wang Z. L. SiO2/Ta2O5 core–shell nanowires and nanotubes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 7773–7778 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W. et al. A general approach to binary and ternary hybrid nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 6, 875–881 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon K.-W. & Shim, M. Gamma-Fe2O3/II-VI sulfide nanocrystal heterojunctions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 10269–10275 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casavola M. et al. Topologically controlled growth of magnetic-metal-functionalized semiconductor oxide nanorods. Nano Lett. 7, 1386–1395 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C., Yu K. F., Cai Y., Fung K. K. & Wang N. Site-specific deposition of titanium oxide on zinc oxide nanorods. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 16712–16716 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C. et al. Zn2TiO4−ZnO Nanowire Axial Heterostructures Formed by Unilateral Diffusion. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 78–82 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Naik V. M., Haddad D., Naik R., Benci J. & Auner G. W. Optical properties of anatase, rutile and amorphous phases of TiO2 thin films grown at room temperature by RF magnetron sputtering. Mat. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 755, DD11.12.1–6 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- David M. K., Du X., Cavanagh A. S. & Weimer A. W. Quantum confinement in amorphous TiO2 films studied via atomic layer deposition. Nanotechnology 19, 445401 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchandani S. & Kamat P. V. Charge-transfer processes in coupled semiconductor systems. Photochemistry and photoelectrochemistry of the colloidal cadmium sulfide-zinc oxide system. J. Phys. Chem. 96, 6834–6839 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Robel I., Bunker B. & Kamat P. V. Single-walled carbon nanotube-CdS nanocomposites as light-harvesting assemblies: Photoinduced charge-transfer interactions. Adv. Mater. 17, 2458–2463 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Vietmeyer F., Seger B. & Kamat P. V. Excited state interactions and charge collection. Adv. Mater. 19, 2935–2940 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Gopidas K. R., Bohorquez M. & Kamat P. V. Charge-transfer processes in colloidal CdS-TiO2 and CdS-AgI systems. J. Phys. Chem. 94, 6435–6440 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Sant P. A. & Kamat P. V. Interparticle electron transfer between size-quantized CdS and TiO2 semiconductor nanoclusters. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 4, 198–203 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Jakob M., Levanon H. & Kamat P. V. Charge distribution between UV-Irradiated TiO2 and gold nanoparticles: determination of shift in the Fermi level. Nano Lett. 3, 353–358 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian V., Wolf E. E. & Kamat P. V. Catalysis with TiO2/gold nanocomposites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 4943–4950 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood A., Giersig M. & Mulvaney P. Fermi level equilibration in quantum dot-metal nanojunctions. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 8810–8815 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian V., Wolf E. E. & Kamat P. V. Green emission to probe photoinduced charging events in ZnO-Au nanoparticles. Charge distribution and fermi-level equilibration. J. Phys. Chem. B 107, 7479–7485 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Djurisic A. B. & Leung Y. H. Optical properties of ZnO nanostructures. Small 2, 944–961 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov S. A. et al. Type-II core/shell CdS/ZnSe nanocrystals: synthesis, electronic structures, and spectroscopic properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 11708–11719 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leelavathi A., Madrasa G. & Ravishankar N. Origin of enhanced photocatalytic activity and photoconduction in high aspect ratio ZnO nanorods. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 10795–802 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Sasaki T., Shimizu Y. & Koshizaki N. Hexagonal-close-packed, hierarchical amorphous TiO2 nanocolumn arrays: transferability, enhanced photocatalytic activity, and superamphiphilicity without UV irradiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 14755–14762 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao B. D. et al. Formation mechanism of sodium titanate nanotubes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, 281–283 (2003). [Google Scholar]