Abstract

Introduction: Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) reflects patient’s glycemic status over the previous 3 months. Previous studies have reported that iron deficiency may elevate A1C concentrations, independent of glycemia. This study is aimed to analyze the effect of iron deficiency anemia on HbA1c levels in diabetic population having plasma glucose levels in control. Methods: Totally, 120 diabetic, iron-deficient anemic individuals (70 females and 50 males) having controlled plasma glucose levels with same number of iron-sufficient non-anemic individuals were streamlined for the study. Their data of HbA1c (Bio-Rad D-10 HPLC analyzer), ferritin (cobas e411 ECLIA hormone analyzer), fasting plasma glucose (FPG, Roche Hitachi P800/917 chemistry analyzer), hemoglobin (Beckman Coulter LH780), peripheral smear examination, red cell indices, and medical history were recorded. Statistical analysis was carried out by student’s t-test, Chi-square test, and Pearson’s coefficient of regression. Results: We found elevated HbA1c (6.8 ± 1.4%) in iron-deficient individuals as compared to controls, and elevation was more in women (7.02 ± 1.58%). On further classification on the basis of FPG levels, A1C was elevated more in group having fasting glucose levels between 100-126 mg/dl (7.33 ± 1.55%) compared to the those with normal plasma glucose levels (<100 mg/dl). No significant correlation was found between HbA1c and ferritin and hemoglobin. Conclusion: This study found a positive correlation between iron deficiency anemia and increased A1C levels, especially in the controlled diabetic women and individuals having FPG between 100-126 mg/dl. Hence, before altering the treatment regimen for diabetic patient, presence of iron deficiency anemia should be considered.

Key Words: Iron deficiency anemia, Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c), Diabetes

Introduction

Iron deficiency is one of the most prevalent forms of malnutrition. Globally, 50% of anemia is attributed to iron deficiency. Ferritin is the storage form of iron, and it reflects the iron status accurately [1]. An earlier study showed that reduced iron stores have a link with increased glycation of hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c), leading to false-high values of HbA1c in non-diabetic individuals [2]. HbA1c is the most predominant fraction of HbA1, and it is formed by the glycation of terminal valine at the β-chain of hemoglobin [3]. It reflects the patient’s glycemic status over previous 3 months. HbA1c is widely used as a screening test for diabetes mellitus, and American Diabetes Association has recently endorsed HbA1c ≥ 6.5% as a diagnostic criterion for diabetes mellitus [4]. Its alteration in other conditions, such as hemolytic anemia, hemoglobinopathies, pregnancy, and vitamin B12 deficiency has been explained in a study conducted by Sinha et al. [5]. Although iron deficiency is the most common nutritional deficiency, reports of the clinical relevance of iron deficiency on HbA1c levels have been inconsistent [2, 5].

In a study carried out by Brooks et al. [2], the HbA1 values were estimated in 35 non-diabetic patients with iron deficiency anemia before and after treatment with iron. They significantly observed elevated HbA1c values in iron deficiency anemia patients and decreased levels after treatment with iron [2]. Similar results were also found in studies carried out by Gram-Hansen et al. [6] and Coban et al. [7]. Investigations performed on diabetic chronic kidney disease patients, and diabetic pregnant women showed increased A1C levels in iron deficiency anemia, which was reduced following iron therapy [8, 9]. In a study by Tarim et al. [10], it was concluded that iron deficiency elevated the A1C levels in diabetic patients when compared with iron-sufficient controls matched for fasting plasma glucose (FPG) levels.

HbA1c is widely used as an important marker of glycemic control, and it is of utter importance to exclude factors which could spuriously elevate its levels. Hence, we conducted a study in iron-deficient individuals with FPG levels below 126 mg/dl to assess whether anemia has any effect on A1C levels, and anemia can be considered before making any therapeutic decisions based solely on HbA1c levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

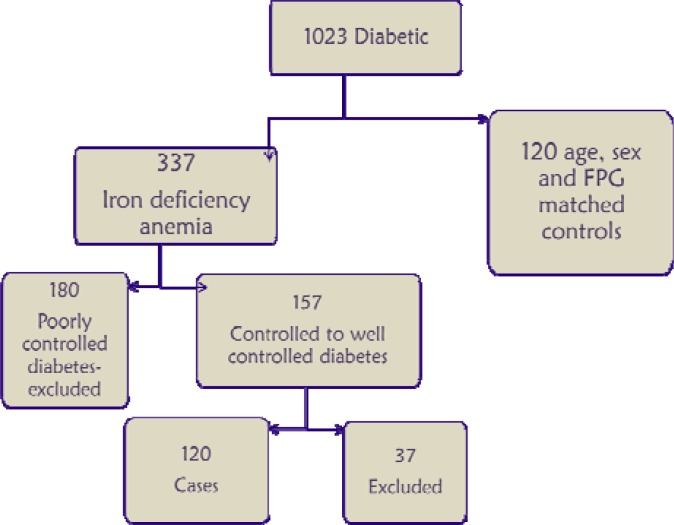

Study population. We used the patients' data of Kasturba Medical College Hospital (KMCH), Ambedkar Circle (India) who consulted during January 2011 to August 2012. The study participants were residents of south India mainly from in and around Mangalore. We collected the data of 1023 diabetic subjects >18 years who already had HbA1c, peripheral smear, hemoglobin, mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), serum ferritin, and plasma glucose levels. Of 1023 diabetic subjects, 337 were diagnosed as having iron deficiency anemia based on their hemoglobin, red cell indices, and peripheral smear, and 157 patients were diabetic having plasma glucose levels in control (FPG <126 mg/dl) since last 6 months. Also, out of 157 patients, 37 were excluded based on other exclusion criteria and 120 subjects (70 females and 50 males) were considered for the study. Then, the patients were divided into well-controlled (FPG <100 mg/dl) and controlled (FPG 100-126 mg/dl) diabetics. Data of HbA1c, peripheral smear, hemoglobin, mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), serum ferritin, and plasma glucose levels was also collected from the non-anemic controls (matched for sex and plasma glucose levels) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Selection of cases and controls

The subjects with microcytic hypochromic peripheral smear, low hemoglobin levels (<12 g% in males and <11 g% in female), predominantly microcytic indices (MCV <76 fL), and hypochromic indices (MCH <27 pg/cell) were considered to have iron deficiency anemia, which was confirmed by low serum ferritin levels (<29 and <20 ng/ml in males and females, respectively). Subjects having FPG >126 mg/dl or random plasma glucose >200 mg/dl or 2-h postprandial plasma glucose >200 mg/dl were excluded from the study. Patients with hemoglobinopathies, hemolytic anemia, hypothyroidism, pregnant patients, and patients having abnormal renal function test (serum urea, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate were also excluded from the study.

Measurements. HbA1c was measured by HPLC method using Bio-Rad D-10 analyzer. Method of estimation and the analyzer used to perform HbA1c analysis were the same throughout the study period. Hemoglobin, MCV, MCH, and MCHC estimation was carried out by Beckman Coulter LH780 automated counter, and serum ferritin estimation was performed by electrochemiluminescence method using Roche/ Hitachi Cobas e411 analyzer. Also, plasma glucose was estimated by glucose oxidase/peroxidase method using Roche Hitachi P800/917 analyzer.

Statistical analysis. Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics 20. The data were presented as mean ± SD. A student’s t-test was applied for comparison of group means. Pearson’s coefficient of correlation was calculated to determine the correlation between the two variables. Categorical data was analyzed by χ2 test. Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals were obtained by the use of logistic regression analyses. P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Subject characteristics. In 120 cases of this study, mean HbA1c value was found to be 6.87 ± 1.4%. The baseline characteristics of the study subjects have been shown in Table 1. The mean ferritin levels in male and female cases were 14.88 ± 8.62 and 8.92 ± 5.72 ng/ml, respectively. Also, mean FPG concentration was 99.66 ± 14.73 mg/dl in total cases. Hemoglobin levels in male and female cases were 9.54 ± 1.4 and 9.37 ± 1.33 g/dl, respectively. The mean MCV was 53.2 ± 8.16 fL and mean MCH was 17 ± 3.7 pg/cell for the all cases (both males and females).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study subjects

|

Female (n = 70)

|

Male (n = 50)

|

Total (n = 120)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDA | NA | IDA | NA | IDA | NA | |||

| Age | 54.65 ± 12.98 | 54.66 ± 12.02 | 56.6 ± 9.5 | 52.1 ± 8.08 | 55.46 ± 11.66 | 53.59 ± 10.59 | ||

| HbA1c | 7.02 ± 1.58* | 5.82 ± 0.53 | 6.67 ± 1.06* | 5.59 ± 0.85 | 6.87 ± 1.4* | 5.65 ± 0.69 | ||

IDA, iron deficiency anemia; NA, no anemia; Values marked with star are statistically significant (P<0.05). As shown in the Table, HbA1c is significantly high in iron-deficient individuals when compared to non-anemic subjects.

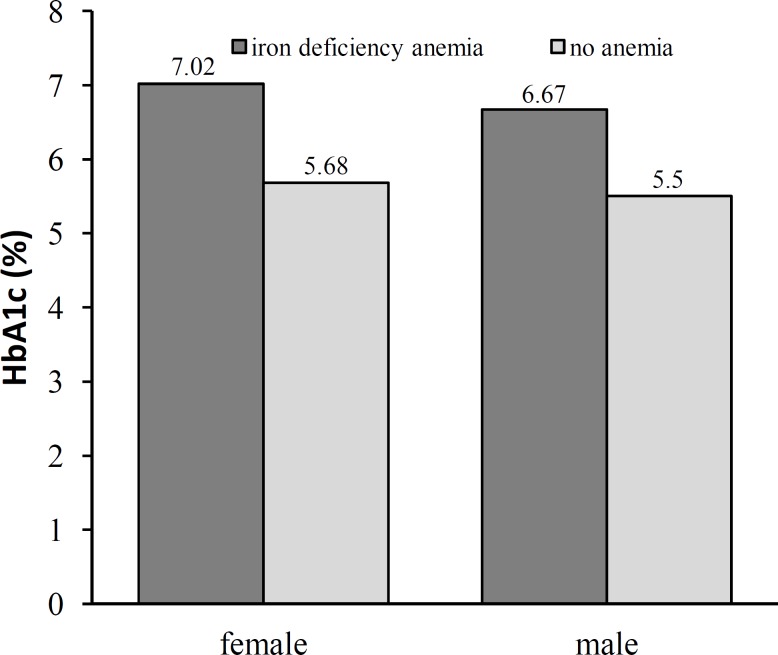

Age, sex, and HbA1c levels. As shown in the Tables 1 and 2, HbA1c was significantly higher in females and in subjects above 50 years of age compared to males and subjects below 50 years of age (Fig. 2). Based on Table 3, odds ratios for HbA1c above 6.5 in age >50 years and in females were statistically non-significant [0.857 (95% CI 0.458-1.604) and 0.690 (95% CI 0.368-1.294), respectively].

Table 2.

Mean HbA1c (%) genderwise in subjects stratified in two groups based on their age

|

Female (n = 70)

|

Male (n = 50)

|

Total (n = 120)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDA | NA | IDA | NA | IDA | NA | |||

| Age <50 | 6.78 ± 1.88 | 5.59 ± 0.51 | 6.54 ± 0.85* | 5.48 ± 0.67 | 6.71 ± 1.64* | 5.53 ± 0.59 | ||

| Age >50 | 7.16 ± 1.37* | 5.91 ± 0.52 | 6.70 ± 1.12* | 5.69 ± 0.94 | 6.94 ± 1.27* | 5.77 ± 0.72 | ||

IDA, iron deficiency anemia; NA, no anemia; Values marked with star are statistically significant (P<0.05). As shown in the Table, iron-deficient subjects older than 50 years have higher HbA1c levels when compared to non-anemic and younger subjects.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of HbA1c (%) genderwise in subjects with iron deficiency anemia and no anemia

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis for effect of sex, fasting plasma glucose (FPG), and age on HbA1c levels shown by odds ratio (95% CI)

|

Female (A1C >6.5)

|

Male (A1C >6.5)

|

Total (A1C >6.5)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |||

| Female sex | 0.690 | 0.368-1.294 | ||||||

| PG 100-126 | 5.602* | 1.923- 16.315 | 2.339 | 0.830-6.593 | 4.078* | 1.919-8.665 | ||

| Age >50 | 0.737 | 0.327-1.659 | 0.760 | 0.333-7.133 | 0.857 | 0.458-1.604 | ||

Values marked with star are statistically significant (P<0.05); CI, Confidence interval. As shown in the Table, patients with FPG levels in pre-diabetes range have higher odds ratio for having HbA1c in diabetic range (>6.5%).

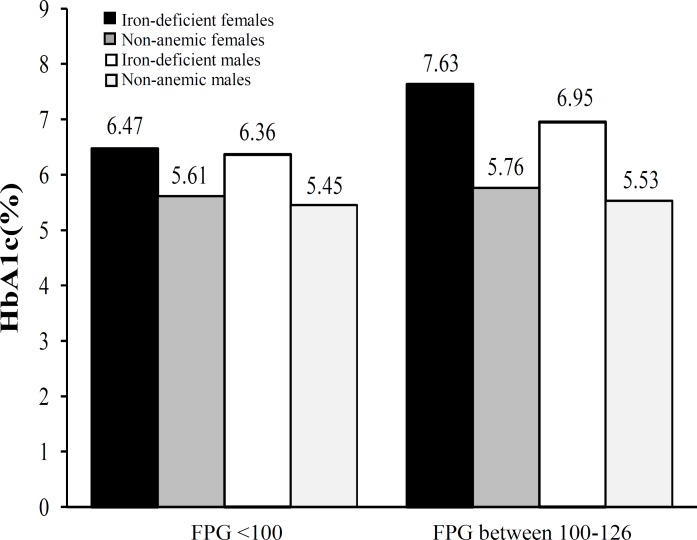

Fasting glucose and HbA1c levels. Mean fasting glucose levels in cases was found to be 99.66 ± 14.73. Subjects were divided into two groups according to their FPG levels. The subjects who had very well-controlled diabetes with normal fasting glucose (FPG levels <100 mg/dl) had HbA1c of 6.43 ± 1.07%, while subjects who had FPG between 100-126 mg/dl had a significantly higher mean A1C value of 7.33 ± 1.55% (Table 4, Fig. 3). Odds ratio for HbA1c >6.5% for subjects with fasting glucose levels between 100-126 was 5 fold higher in females and 4 fold higher in total population, but it was non-significant in males.

Table 4.

Mean HbA1c (%) genderwise in subjects stratified in two groups based on their fasting plasma glucose (FPG) levels

|

Female (n = 70)

|

Male (n = 50)

|

Total (n = 120)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDA | NA | IDA | NA | IDA | NA | |||

| HbA1c in FPG <100 | 6.47 ± 1.19* | 5.61 ± 0.58 | 6.36 ± 0.88* | 5.45 ± 0.67 | 6.43 ± 1.07* | 5.46 ± 0.62 | ||

| HbA1c in FPG 100-126 | 7.63 ± 1.76* | 5.96 ± 0.46 | 6.95 ± 1.15* | 5.83 ± 1.00 | 7.33 ± 1.55* | 5.89 ± 0.75 | ||

IDA, iron deficiency anemia; NA, no anemia; Values marked with star are statistically significant (P<0.05). As shown in the Table, patients with FPG in pre-diabetes range have higher HbA1c levels when compared to those with FPG <100 mg/dl and non-anemic subjects.

Fig. 3.

HbA1c levels in patients having fasting plasma glucose (FPG) below 100 and between 100-126

Hemoglobin, ferritin, and HbA1c. Mean hemo-globin and ferritin levels for cases were found to be 9.44 ± 1.36 and 11.41 ± 7.63, respectively. Pearson’s coefficient of correlation was statistically non-significant for hemoglobin and HbA1c (r = 0.202, P = 0.064) as well as for HbA1c and ferritin (r = - 0.05, P = 0.295).

Discussion

HbA1c is the most frequently occurring fraction of hemoglobin A1. In the process of glycation, glucose in the red cells reacts with N-terminal valine of both beta

chains to form an aldimine linkage which undergoes rearrangement forming a more stable ketoamine link [11, 12]. American Diabetes Association guidelines have not only considered it as the primary target for glycemic control but also included it as a diagnostic criterion. Initially, it was believed that HbA1c was only altered by glucose levels [13-15]; however, certain studies have noted its elevation in conditions other than diabetes, such as hemoglobinopathies, chronic kidney diseases, pregnancy, and nutritional anemias [2, 8, 9].

Iron deficiency anemia is one the most common anemia amongst the nutritional anemias in India. Initial studies conducted by Brooks et al. [2], Gram-Hansen et al. [6], and Coban et al. [7] showed effects of iron therapy on glycated hemoglobin and found a significant reduction in HbA1c levels after iron therapy in non-diabetic population [2, 6, 7]. According to the explanation provided by Sluiter et al. [16], hemoglobin glycation is an irreversible process. Hence, HbA1 levels in erythrocyte will be increased with cell age. In iron deficiency, red cell production decreases, consequently an increased average age of circulating red cells ultimately leads to elevated HbA1 levels [16]. According to some workers, the changes in HbA1c levels were due to different laboratory methods used to analyze it. Goldstein et al. [17] demonstrated that HbA1c measured by HPLC was increased two hours after a standard breakfast and incubating the red cell in 0.9% saline at 37°C for five hours eliminated this increment [17], which was explained by presence of labile HbA1c. This effect was eliminated by reagents used in newer enzymatic kits. Rai and Pattabiraman [18] conducted a study to evaluate different methods used to analyze HbA1c and found no significant difference between them [18]. However, in a study by Tarim et al. [10], the results were inconclusive with some subjects showing elevation in A1C, while some showed no elevation. In a study carried out by Hashimoto et al. [19], A1C levels were elevated in pregnant diabetic women. Pregnancy is another condition which can cause spurious A1C elevation. Pregnancy is mostly associated with iron deficiency anemia. The study showed that it was iron deficiency anemia which caused elevated A1C, and not pregnancy itself. Hence, Hashimoto and co-workers [19] concluded that it should not be used as a marker of glycemic control, especially in later half of pregnancy. Similarly in a study conducted on chronic kidney diseases patients with diabetes by Jen et al. [8], the status of glycemic control could not be determined due to presence of iron deficiency anemia [8]. Therefore, iron deficiency anemia not only increases A1C levels in non-diabetic individuals but also it can interfere with its ability to determine glycemic status of diabetic individuals.

Different studies have been carried out in both diabetic and non-diabetic groups; however, its distribution in well-controlled diabetics who are on regular therapy is inadequately studied. Although diabetes itself can elevate the A1C levels, it has been proven that controlled plasma glucose levels for 3 months correlates very well with controlled HbA1c. Hence, patients with controlled plasma glucose levels are expected to have A1C below 6.5 % [4].

As shown in the results, there was a significant elevation in A1C levels in iron-deficient anemic individuals with FPG less than 126. Therefore, we studied HbA1c distribution after dividing the individuals into various groups according to their age, sex, and plasma glucose levels.

In a study conducted by Davidson et al. [20], HbA1c showed a very minor positive correlation with age [20]. This result can be explained by a study showing no change in erythrocyte survival in aged people compared to young people [21]. Our study showed a higher mean value of A1C in people older than 50 years. However, the probabilities of higher A1C in diabetics were statistically non-significant, and age did not show any significant correlation with HbA1c. Hence, our findings nullify the role of elderly age in elevating A1C in iron-deficient individuals. Koga et al. [22] found that red cell counts and A1C were associated positively, while A1C and red cell indices as well as hemoglobin were associated negatively in non-diabetic premenopausal women. In addition, post menopausal women did not show any significant association [22]. This study shows higher levels of A1C in females both in pre and postmenopausal groups, but the probability of having an A1C above 6.5 was low and statistically non-significant. A1C was more in postmenopausal compared to premenopausal women. In a study by Dasgupta et al. [23], no significant difference in HbA1c levels were noted in postmenopausal and premenopausal women irrespective of anemia [23]. Our findings suggest that anemia has a predominant role in elevating A1C in postmenopausal compared to premenopausal women, especially in the presence of diabetes even with controlled plasma glucose levels. Elevated A1C levels were also found in males, but again odds ratio was not significant. Various studies have been carried out in diabetic individuals to assess the reliability of A1C as a prognostic marker and in non-diabetic individuals to assess its reliability to diagnose diabetic mellitus [8, 10]. Diabetic patients who are on treatment are goaled to bring their A1C levels up to 6%, as it correlates with random plasma glucose levels of 126 mg/dl. This goal is often not achieved and treatment regimen is often changed [4]. Our observation showed that conditions such as iron deficiency anemia can spuriously elevate A1C levels; consequently care should be taken before altering treatment regimen. Our observation also showed significantly higher A1C levels in anemic patients who had FPG between 100-126 mg/dl. As a result, anemia may exaggerate the picture of glycemic status in this group of patients. Our study showed mean A1C of around 6.4% for the patients with FPG levels <100 mg/dl which were higher than those of controls. Thus iron deficiency anemia has role in elevating A1C in both the groups.

Ferritin is a storage form of iron, and it reflects the true iron status [1]. Hence, in this study, its correlation with HbA1c was assessed, but no significant correlation was found. As explained previously, in iron deficiency anemia, ferritin is decreased with increase in the red cell life span, and increased red cell life span is associated with increased HbA1c. However, one of the studies did not show any significant correlation of serum ferritin levels and red cell life span [24], indicating the lack of significant correlation between ferritin and HbA1c in our study. Various studies have shown elevated ferritin in diabetic population, though its mechanism is still debatable. In a study by Raj and Rajan [25], ferritin showed positive correlation with HbA1c in diabetic individuals. In addition, Canturk et al. [26] found that serum ferritin was elevated as long as glycemic status was not achieved, thus they found normal ferritin levels in diabetic individuals. Sharifi and Sazandeh [27] did not find any significant correlation between HbA1c and ferritin in diabetic population. We could not explain the lack of correlation of serum ferritin levels with HbA1c in this study. Our study did not show any significant correlation between hemoglobin and HbA1c (r = 0.202, P = 0.064). When correlation for red cell indices and HbA1c in anemic subjects was studied, no significant correlation was found between HbA1c and MCV (r = -0.23, P = 0.06), and borderline significant association was found between HbA1c and MCH (r = -0.58, P = 0.05). Although association of elevated A1C with severity of iron deficiency anemia remains unexplained, its borderline association with red cell indices proves the role of erythrocyte morphology and lifespan in elevating A1C.

Though we tried to collect as much data as possible for inclusion and exclusion of subjects in our study, some data might have been missed. We could not conclude any effect of BMI on HbA1c levels due to the lack of sufficient data. We could not get the follow up data of patients after iron therapy, which might have given a new dimension to our study.

Iron deficiency anemia elevates HbA1c levels in diabetic individuals with controlled plasma glucose levels. The elevation is more in patients having plasma glucose levels between 100 to 126 mg/dl. Hence, before altering the treatment regimen for diabetes, iron deficiency anemia should be considered.

References

- 1.John A. Iron Deficiency and Other Hypoproliferative Anemias. In: Longo D, Fauci A, Kasper D, Hauser S, Jameson J, Loscalzo J, editors , editors. Principles of Internal Medicine by Harrisons. 17th ed. United States of America: McGraw-Hill; 2008. pp. 628–35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks AP, Metcalfe J, Day JL, Edwards MS. Iron deficiency and glycosylated haemoglobin A1. Lancet. 1980 Jul;316(8186) doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim C, Bullard KM, Herman WH, Beckles GL. Association between iron deficiency and A1C levels among adults without diabetes in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2006. Diabetes Care. 2010 Apr;33 doi: 10.2337/dc09-0836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2011. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):S13. doi: 10.2337/dc11-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinha N, Mishra TK, Sinha T, Gupta N. Effect of iron deficiency anemia on hemoglobin A1c levels. Ann Lab Med. 2012 Jan;32(1):17–22. doi: 10.3343/alm.2012.32.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gram-Hansen P, Eriksen J, Mourits-Andersen T, Olesen L. Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in iron- and vitamin B12 deficiency. J Intern Med. 1990 Feb;227(2):133–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1990.tb00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coban E, Ozdogan M, Timuragaoglu A. Effect of iron deficiency anemia on the levels of hemoglobin A1c in nondiabetic patients. Acta Haematol. 2004;112(3):126–8. doi: 10.1159/000079722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ng JM, Cooke M, Bhandari S, Atkin SL, Kilpatrick ES. The effect of iron and erythropoietin treatment on the A1C of patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Care. 2010 Nov;33(11):2310–3. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rafat D, Rabbani TK, Ahmad J, Ansari MA. Influence of iron metabolism indices on HbA1c in non-diabetic pregnant women with and without iron-deficiency anemia: effect of iron supplementation. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2012 Apr-Jun;6(2):102–5. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarim O, Küçükerdoğan A, Günay U, Eralp O, Ercan I. Effects of iron deficiency anemia on hemoglobin A1c in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Int. 1999 Aug;41(4):357–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.1999.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mortensen HB, Christophersen C. Glucosylation of human haemoglobin A in red blood cells studied in vitro. Kinetics of the formation and dissociation of haemoglobin A1c. Clin Chim Acta. 1983 Nov;134(3):317–26. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(83)90370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mortensen HB, Vølund A, Christophersen C. Glucosylation of human haemoglobin A. Dynamic variation in HbA1c described by a biokinetic model. Clin Chim Acta. 1984 Jan;136(1):75–81. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(84)90249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahbar S. An abnormal hemoglobin in red cells of diabetes. Clin Chim Acta. 1968 Oct;22(2):296–8. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(68)90372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahbar S, Blumenfeld O, Ranney HM. Studies of an unusual hemoglobin in patients with diabetes mellitus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1969 Aug;36(5):838–43. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(69)90685-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trivelli LA, Ranney HM, Lai HT. Hemoglobin components in patients with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1971 Feb;284(7):353–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197102182840703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sluiter WJ, van Essen LH, Reitsma WD, Doorenbos H. Glycosylated haemoglobin and iron deficiency. Lancet. 1980;2:531–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91853-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein DE, Peth SB, England JD, Hess RL, Da Costa J. Effects of acute changes in blood glucose on HbA1c. Diabetes. 1980 Aug;29(8):623–8. doi: 10.2337/diab.29.8.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rai KB, Pattabiraman TN. Glycosylated haemoglobin levels in iron deficiency anemia. Indian J Med Res. 1986 Feb;83:234–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimoto K, Noguchi S, Morimoto Y, Hamada S, Wasada K, Imai S, et al. A1C but not serum glycated albumin is elevated in late pregnancy owing to iron deficiency. Diabetes Care. 2008 Oct;31(10):1945–8. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davidson MB, Schriger DL. Effect of age and race/ethnicity on HbA1c levels in people without known diabetes mellitus: implications for the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010 Mar;87(3):415–21. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurdle ADF, Rosin AJ. Red cell volume and red cell survival in normal aged people. J Clin Pathol. 1962 Jul;15(4):343–5. doi: 10.1136/jcp.15.4.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koga M, Morita S, Saito H, Mukai M, Kasayama S. Association of erythrocyte indices with glycated haemoglobin in pre-menopausal women. Diabet Med. 2007 Aug;24(8):843–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dasgupta S, Salman M, Lokesh S, Xaviour D, Saheb SY, Prasad BV, et al. Menopause versus aging: The predictor of obesity and metabolic aberrations among menopausal women of Karnataka, South India. J Midlife Health. 2012 Jan;3(1):24–30. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.98814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weight LM, Byrne MJ, Jacobs P. Haemolytic effects of exercise. Clin Sci (Lond) 1991 Aug;81(2):147–52. doi: 10.1042/cs0810147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raj S, Rajan GV. Correlation between elevated serum ferritin and HbA1c in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Res Med Sci. 2013;1(1):12–15. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canturk Z, Çetinarslan B, Tarkun I, Canturk NZ. Serum ferritin levels in poorly‐ and well‐controlled diabetes mellitus. Endocr Res. 2003 Aug;29(3):299–306. doi: 10.1081/erc-120025037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharifi F, Sazandeh SH. Serum ferritin in type 2 diabetes mellitus and its relationship with HbA1c. Acta Medica Iranica. 2004;42(2):142–5. [Google Scholar]