Abstract

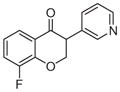

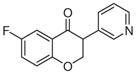

Fluorinated isoflavanones and bifunctionalized isoflavanones were synthesized through a one-step gold(I)-catalyzed annulation reaction. These compounds were evaluated for their in vitro inhibitory activities against aromatase in a fluorescence-based enzymatic assay. Selected compounds were tested for their anti-proliferative effects on human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Compounds 6-methoxy-3-(pyridin-3-yl)chroman-4-one (3c) and 6-fluoro-3-(pyridin-3-yl)chroman-4-one (3e) were identified as the most potent aromatase inhibitors with IC50 values of 2.5 μM and 0.8 μM. Therefore, these compounds have great potential for the development of pharmaceutical agents against breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Estrogen, Aromatase inhibitors, Fluorine, Isoflavanones, Functional groups

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer found in women worldwide, and it is reported that one in every eight women develops metastatic breast cancer in their lifetime.1 There is a high concentration of estrogen in breast tissue, therefore the risk of developing breast cancer increases greatly.2 In addition, immature breast tissue cells allow stronger binding of carcinogens to breast tissue cells and they possess lower DNA repair capacity. Aromatase is a cytochrome P450 enzyme that has been found to catalyze the last and rate-limiting step of endogenous estrogen synthesis. Chemically, aromatase catalyzes the oxidation and aromatization of androgens (testosterone and androstenedione) to estrogens (estrone and estradiol).3 Aromatase is present in breast tissue and is the source of local estrogen production in breast cancer tissues.4 Since 75% of breast cancer tumors are hormone-dependent, interfering with the production of estrogen using aromatase inhibitors (AIs) is a validated target. In this work, we expand on the types of AIs currently available by reporting for the first timemore potent isoflavanone AIs that have not been explored previously.

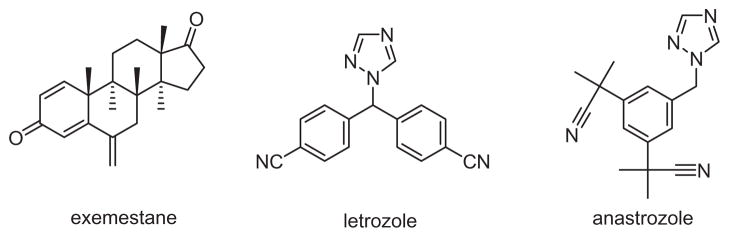

There are two types of AIs: steroidal (type I inhibitors) and nonsteroidal (type II inhibitors), based on their chemical structure.5 Steroidal AIs (e.g., exemestane in Fig. 1) are mechanism-based inhibitors which bind to the enzyme active site irreversibly. On the other hand, many nonsteroidal AIs (e.g., letrozole and ananstrozole in Fig. 1) bind to the enzyme’s active site reversibly by non-covalent interactions such as heme iron coordination, hydrogen bonding, etc. Both types of AIs serve to block the aromatase function in order to prevent its estrogen production. AIs have been used in the treatment of hormone-dependent breast cancer and have shown clear superiority compared with the traditional treatment selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) such as tamoxifen.6

Figure 1.

Structures for steroidal (exemestane) and nonsteroidal (letrozole, anastrozole) aromatase inhibitors.

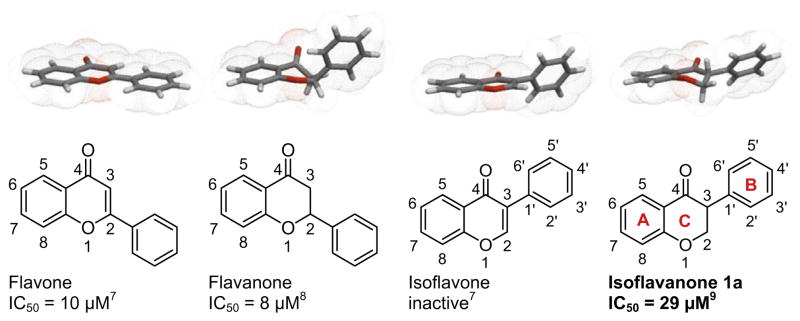

Flavonoids have been shown to have antiviral, anti-inflammatory, antimutagenic and anticarcinogenic activities. Some naturally occurring flavones, flavanones and isoflavones have been reported to inhibit aromatase and affect breast cancer cell proliferation. Being a rare class of natural products, the aromatase inhibition effects of isoflavanones were scarcely reported. The aromatase inhibition potencies of flavonoid core structures are summarized in Figure 2. It is interesting to note the different activities exhibited by flavone, flavanone and isoflavone. Unlike flavone or flavanone which showed moderate inhibition against aromatase, isoflavone is inactive toward aromatase.7,8 In our previous study, we showed for the first time that an isoflavonone-based AI 1a was active against aromatase with an IC50 value of 29 μM, probably due to increased hydrophobic interactions between isoflavanone and the aromatase active site.9 This indicated the potential medicinal value of this subclass of flavonoid compounds.

Figure 2.

Structures and aromatase inhibitory effects of flavonoid compounds.

Fluorinated drugs have been a very popular topic in the field of pharmaceutical science.10 In the past 50 years, approximately 20% of pharmaceuticals contain one or more fluorine atoms.11 The rate of introduction of fluorinated drugs has increased compared to past years. Fluorine has effects on several properties of drug molecules including: drug–target interactions and specificity, metabolic stability, acidity or basicity, membrane permeability and toxicity. It has been used as a bioisostere for H, OH and NH2 groups to modulate bioactivity and the pharmacological properties of medicines. 12 The fluorine atom is highly electronegative and small. The addition of fluorine to an aryl ring or other π-system increases the lipophilicity as a result of electron donation of fluorine lone pair electrons by resonance.13 The short contacts involving fluorine atoms between proteins and fluorinated ligands are very frequent, and they may increase the fluorinated molecule’s binding affinity for the enzyme.11,14 Thus, fluorine has played and will continue its important role in drug design.15

To expand on this important new isoflavanone scaffold, we chose to explore fluorinated and bifunctionalized AIs. Herein we report our effort to optimize isoflavanone AIs through structure-activity relationship analysis and enhanced binding interaction design identified via computation. The enzymatic and cell-based assays were used to evaluate the biological activities. Computational docking of the AIs into the aromatase active site was used to determine the crucial interactions that occur within the enzyme pocket. The physiochemical properties such as LogP, number of hydrogen bond donors, number of hydrogen bond acceptors and polar surface area were also calculated to gain some insight into their pharmacokinetic effects. Selected compounds from isoflavanone AIs were tested further for their anti-proliferative effects on human breast cancer cells. The bioactivity and physicochemical properties exhibited by these isoflavanone compounds provide useful information to develop more potent yet less toxic aromatase inhibitors.

2. Results

2.1. Design and synthesis of fluorinated and bifunctionalized isoflavanone compounds

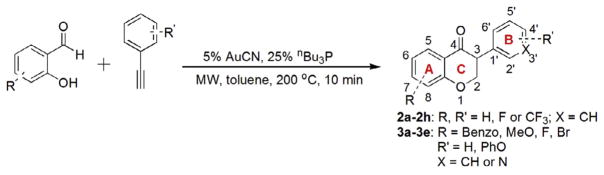

For the beneficial effects of fluorine mentioned above, eight fluorinated isoflavanones 2a–2h were synthesized according to Scheme 1 and evaluated for their biological activities. A microwave- assisted, gold(I)-catalyzed annulation reaction of fluorinated hydroxyaldehydes and phenylacetylenes was utilized to synthesize these isoflavanones.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of fluorinated isoflavanone AIs (2a–2h) and bifunctionalized isoflavanone AIs (3a–3e).

Compared to AI clinical drugs, the molecular weights and polar surface areas of the isoflavanone AIs previously synthesized in our lab were relatively small. For example, the polar surface areas (PSA) for 6-bromo-3-phenylchroman-4-one 1b (PSA = 26.3 Å2), 3-(biphenyl-4-yl)chroman-4-one 1c (PSA = 26.3 Å2), 3-(4-Phenoxyphenyl) chroman-4-one 1d (PSA = 35.3 Å2) and 3-(pyridin-3-yl)chroman-4-one 1e (PSA = 39.2 Å2) were only about half of that for letrozole (PSA = 78.3 Å2). This provided additional opportunities to modify these AIs with additional functional groups. The development of an aromatase inhibitor with multiple functional groups is an attractive concept as this single agent should inhibit estrogen biosynthesis by binding to the aromatase through two or more of the following interactions: hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding and heme iron coordination. In addition, the extra functional groups can be used to fine tune the physicochemical properties of AIs so that desirable bioavailability and pharmacokinetic properties can be achieved. Therefore, five bifunctionalized isoflavanones 3a–3e were synthesized according to Scheme 1 and tested for their inhibitory effects against aromatase. The structures of fluorinated isoflavanones 2a–2h and bifunctionalized isoflavanones 3a–3e are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Structure, calculated physicochemical properties, predicted toxicity and experimental aromatase inhibitory potencies of isoflavanone AIs 2a–2h and 3a–3e

| Structure | ID | LogPa | Hab | Hdc | PSA (Å2)d | Toxicitye

|

IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mut/tum/irr/rep | |||||||

|

2a | 3.54 | 2 | 0 | 26.3 | L/L/L/L | 32 ± 7f |

|

2b | 3.51 | 2 | 0 | 26.3 | L/L/L/L | 15 ± 9f |

|

2c | 3.63 | 2 | 0 | 26.3 | L/L/L/L | N.A.g |

|

2d | 3.04 | 2 | 0 | 26.3 | L/L/L/M | 24 ± 8f |

|

2e | 3.54 | 2 | 0 | 26.3 | L/L/L/M | 35 ± 5f |

|

2f | 3.56 | 2 | 0 | 26.3 | L/L/L/M | 33 ± 12f |

|

2g | 3.65 | 2 | 0 | 26.3 | L/L/L/M | 20 ± 11f |

|

2h | 4.29 | 2 | 0 | 26.3 | L/L/L/L | N.A.g |

|

3a | 6.31 | 3 | 0 | 35.5 | H/L/L/L | 190 ± 25f |

|

3b | 5.19 | 4 | 0 | 44.8 | H/L/L/L | N.A.g |

|

3c | 1.71 | 4 | 0 | 48.4 | L/L/L/L | 2.5 ± 1.1f |

|

3d | 1.83 | 3 | 0 | 39.2 | L/L/L/L | 67.1 ± 4f |

|

3e | 1.83 | 3 | 0 | 39.2 | L/L/L/L | 0.8 ± 0.5f |

| Letrozole | 2.15 | 5 | 0 | 78.3 | H/L/M/M | 0.0028 ± 0.0006f |

LogP, calculated logarithm of partition coefficient between n-octanol and water.

Ha, hydrogen bond acceptor.

Hd, hydrogen bond donor.

PSA, polar surface area.

Toxicity includes mutagenic, tumorigenic, irritating and reproductive effects. L, low; M, medium; H, high.

IC50 values are average of three runs.

Inactive in enzymatic assay.

2.2. Aromatase inhibition activities of fluorinated and biofunctionalized AIs

Aromatase inhibition was determined by using a fluorogenic substrate (7-methoxy-trifluoromethylcoumarin) and human CYP 19 aromatase with ketoconazole as positive control.16 Each compound was tested in triplicate measurements and the average IC50 value can be seen in Table 1. Fluorinated isoflavanone 2b showed stronger inhibitory effects against aromatase compared to the parent molecule 1a while compounds 2c and 2h were inactive. No significant inhibition occurred with bifunctionalized isoflavanones 3a and 3b. Bifunctionalized isoflavanones 3c and 3e showed improved inhibition against aromatase.

Also shown in Table 1 are the calculated important physicochemical properties (partition coefficient between n-octanol and water logP, number of hydrogen bond donors Hd, number of hydrogen bond acceptors Ha and polar surface area PSA) and predicted toxicity profiles for these AIs. The calculation of physicochemical properties was performed using Molinspiration Cheminformatics software at URL http://www.molinspiration.com. Prediction of mutagenic, tumorigenic, irritating and reproductive toxicities was achieved utilizing OSIRIS Property Explorer software at URL http://www.organic-chemistry.org/prog/peo/.17

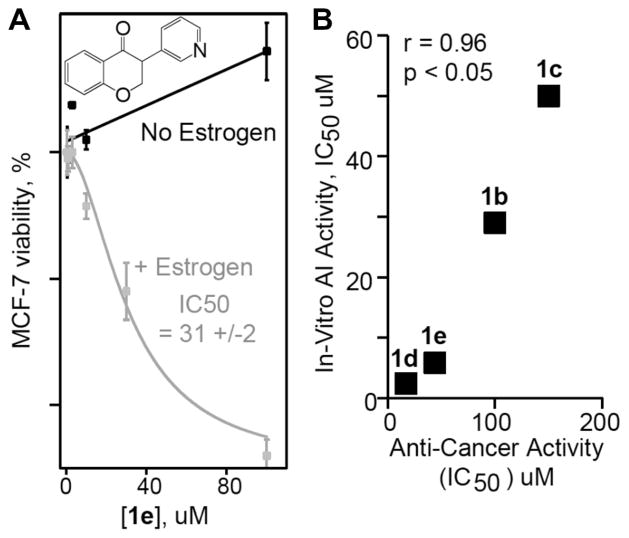

2.3. Estrogen-dependent MCF-7 growth inhibition

Examination in human breast cancer cells of the synthesized compounds was accomplished. As a starting point, compounds 1b–e were examined for activity in MCF-7 breast cancer cells using letrozole as a positive control.18 To examine activity, MCF-7 cells were grown under two different conditions. First, as is standard MCF-7 cells were raised in estrogen, low picomole, which has been shown to increase both estrogen and estrogen receptor content.19 With added estrogen the doubling time was twice as fast and stabilized over 10 days. The doubling rate increased more than 2-fold during this period. In contrast, MCF-7 cells raised without estrogen and phenol red displayed an altered phenotype, grew more slowly, and importantly had reduced sensitivity towards anti-estrogen molecules including flavenoids.20 Examination of the positive control, letrozole, a well-known AI with estrogen-dependent activity in the low nanomolar range was performed. These cells were incubated with letrozole at low nanomolar concentrations. The IC50 value for letrozole is 7 ± 3 nM and is similar to literature values of 20 nM.21 The novel AIs were then examined for differential activity against estrogen-dependent MCF-7 cells. Viability plots with and without estrogen for compound 1e are shown in Figure 3a. When non-estrogen dependent MCF-7 cells were incubated with 3c, no growth inhibition was observed. In fact, cells tended to grow faster than controls likely due to non-specific estrogen mimicking since MCF-7 is known to overexpress estrogen receptors. Similar experiments using estrogen-dependent MCF-7 cells showed high activity. The IC50 value for 1e was 31 ± 2 μM. Thus, the new AIs in this report require estrogen-dependent growth to induce anti-cancer activity.

Figure 3.

Potency of AIs in estrogen-dependent MCF-7. (a) Estrogen-dependent (grey) and estrogen independent (black) anti-cancer activity of Compound 1e. Compound 1e requires estrogen-dependent cells to inhibit cell growth (compare grey and black). (b) The relationship of anti-cancer anti-aromatase activity. The correlation coefficient is 0.96 and p less than 0.05 showing strong correlation between in vitro and cellular experiments.

The estrogen-dependent IC50 values for 1b, 1c, 1d and 1e were obtained. The relationship between aromatase inhibition and anticancer cell activity was examined (Fig. 3b). For example, the inactive AI 1c did not show anti-cancer cell activity. Thus, 1c was given a value of 150 as this is the upper detection limit. The moderate AI 1b showed moderate anti-proliferative activity on MCF-7 cell assay with an IC50 value of 100 ± 11 μM. The cellular IC50 values for good AIs 1d and 1e are 17 μM and 44 μM, respectively (Fig. 3b). The correlation coefficient for this set of five molecules is 0.96 and the p value is less than 0.05. In addition it should be noted that the letrozole shows the same trend with correspondingly lower in vitro and cellular activities. This data demonstrate that the cellular anti-cancer activity of these new AIs correlates with in vitro aromatase inhibition.

The most active AIs from the enzymatic assay 3c and 3e were also tested for their anti-proliferative activities on MCF-7 cell assays. Unfortunately, these two compounds turned out to be inactive in the cell assay. Since the presence of the pyridyl group increased the bioactivity as seen in AI 1e, the observed inactivity for compounds 3c and 3e is probably related to the substituents at the C6 position. On the other hand, the C8 substituted compound 3d showed good anti-proliferative activity in the MCF-7 cell assay with an IC50 value of 43 ± 6 μM.

2.4. Docking poses for isoflavanone AIs

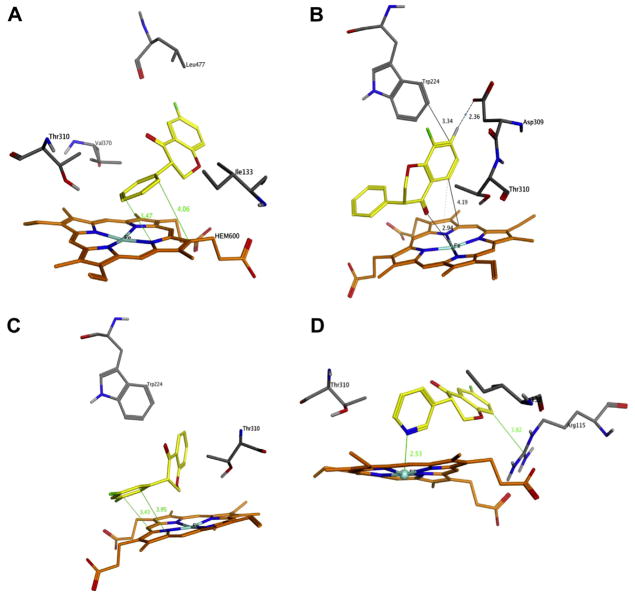

Both enantiomers of synthesized isoflavanones were docked into the aromatase active site (PDB code 3EQM),22 and the enantiomer with the higher docking score was used to identify crucial enzyme/inhibitor interactions. The factors which were taken into account in the docking score included external hydrogen bonds, external van der Waals interactions, internal hydrogen bonds, internal torsion and internal van der Waals interactions. The top docking scores for active isoflavanone AIs 2a, 2b, 2g and 3e were 55.2, 53.9, 56.3 and 56.9 kJ/mol. The dominant interactions for 6-fluoroisoflavanone 2a (Fig. 4a) and 3′, 5′-difluoroisoflavanone 2g (Fig. 4c) predicted by docking poses were π–π stacking interactions between the isoflavanone B ring and the heme group in the enzyme active site.

Figure 4.

Representations of molecular docking performed in this study. The inhibitor is depicted in yellow sticks. The heme group is shown in orange. Selected relevant amino acid residues in aromatase are shown as sticks (white, H; black, C; blue, N; red, O). Lines are drawn between the atoms likely involved in hydrogen bonding or heme coordination. (a) 6-fluoroisoflavanone 2a; (b) 8-fluoroisoflavanone 2b; (c) 3′,5′-difluoroisoflavanone 2g. (d) 6-fluoro-3-(pyridin-3-yl)chroman-4-one 3e.

The binding interactions between 8-fluoroisoflavanone 2b (Fig. 4b) and the aromatase active site were more complicated than those of 2a and 2g. At least three different types of interactions were noticed from our study: heme iron coordination, π–π stacking interactions and hydrogen binding. Specifically, the C4 carbonyl of 2b coordinates to the heme iron with a predicted distance of 2.9 Å. Carbonyl-heme iron coordination is common for isoflavanone AIs, and it has been observed for 2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-benzo[f]chromen-1-one,3-(4-phenoxyphenyl)chroman-4-one and 3-(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)chroman-4-one in our previous study.9 The π–π stacking interactions are frequently involved in binding modes between the ligand and aromatase amino acid residues such as Phe 221, Trp 224 or the heme group. Compound 2b showed π–π stacking interactions with Trp 224 (distance = 3.3 Å). The hydrogen binding interactions between the C7-H of 2b and the enzyme amino acid residue Asp309 (distance = 2.4 Å) were also predicted in the docking study.

The bifunctionalized isoflavanone 3e was docked into the enzyme active site and its docking pose is shown in Figure 4d. The crucial interactions between compound 3e and the enzyme active site included the following: first, the coordination between the 3e pyridyl nitrogen and the heme iron atom (distance = 2.5 Å); second, the interaction between the A ring of 3e and the enzyme amino acid residue Arginine 115 (distance = 3.8 Å). The pyridyl nitrogen and heme iron coordination is the most important interaction for heterocyclic isoflavanones as it was also observed in our previous study for compounds such as 3-(pyridin-3-yl)chroman-4-one.9 Even though the amino acid residue Thr 310 showed ligand exposure in the docking study, there were no obvious hydrogen bonding interactions between the Thr 310 side chain OH and the 3e pyridyl nitrogen.

3. Discussion

3.1. The effect of fluorine on isoflavanone AIs

The addition of fluorine atoms on the isoflavanone scaffold did not improve the calculated physicochemical properties and predicted toxicity profiles significantly when compared with their parent molecule 1a. Among the physicochemical properties listed in Table 1, the most important factor is Log P which measures the solubility and permeability of orally-active drug molecules. A drug-like molecule usually has a LogP value between 0 and 3.23 Most of the fluorinated isoflavanones had logP values around 3.50 (Table 1), similar to the parent molecule 1a which had a logP value of 3.40, indicating potential poor bioavailability. Thus, the physicochemical properties of these compounds could be further modulated by installing additional polar functional groups. The fluorinated isoflavanone AIs usually exhibited low to medium predicted toxicity profiles. The active fluorinated isoflavanones 2b and 2g were predicted to have low mutagenic, tumorigenic and irritating toxicity profiles (Table 1).

The unique hydrogen binding pattern between the C7-H of 8-fluoroisoflavanone 2b and the enzyme amino acid residue Asp309 indicates the increased acidity of isoflavanone compounds in the presence of fluorine. Namazian reported that fluorine substituents could significantly increase the gas-phase acidity of benzene,24 which might make the aromatic ring more capable of forming hydrogen bonds. Also, it has been noticed that β-fluorination invariably increases C–H acidity due to the stabilization of the carbanion by the inductive effect and hyperconjugative resonance. 13a Given these facts and the strong electronegativity of fluorine, the observed hydrogen bonding might result from the increased acidity of C7-H and the close proximity with Asp309.

The active site of aromatase (CPY19) is highly hydrophobic. By the addition of fluorine the binding affinity might increase as seen with the most potent compound 8-fluoroisoflavanone 2b.

The hydrophobic interactions between the B ring of 3′,5′-difluoroisoflavanone 2g and the heme porphyrin (distance = 3.4–3.9 Å, Fig. 4c) increased when compared with compound 2a which has no fluorine on its B ring (distance = 3.5–4.1 Å, Fig. 4a). This can be explained from the effect of fluorine substituents on lipophilicity. Although there are might be exceptions, aromatic fluorination or fluorination adjacent to atoms with π bonds usually increases lipophilicity due to the resonance donor nature of fluorine.13a The effects of fluorine substituents are additive and with each additional fluorine, the compound becomes increasingly lipophilic15 and its LogP value becomes larger. The logP values for non-, mono- and difluorinated isoflavanones 1a, 2a and 2g are 3.40, 3.51 and 3.65, respectively. Therefore, the hydrophobic interactions increased from compound 2a to 2g.

3.2. The effect of bifunctional groups on isoflavanone AIs

The addition of a second functional group serves the following purposes: first, to enhance the enzyme/substrate binding interactions through multiple binding sites; second, to fine-tune the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics properties of potential drug molecules. Methoxyl, phenoxyl, benzo, halogens and pyridyl groups on the isoflavanone scaffold have resulted in favorable interactions with aromatase.9 Since the C6 position is very important for enzymatic bioactivity of isoflavanone AIs, the second functional group was mostly installed at the C6 position.

Compounds 3a and 3b were designed based on the structure-activity relationships of their active precursors. Specifically, we found in our previous study that 4′-PhO, 6-CH3O and 5,6-benzo groups significantly improved the aromatase inhibitory potencies of isoflavanone compounds. It was expected that the enzyme/inhibitor binding interactions could be enhanced by bringing the favorable functional groups together. Even though the calculated physicochemical properties of these compounds were not perfect, as seen by the poor Log P values and predicted high mutagenic toxicity in Table 1, the high activity of their precursors in enzyme assays justify the synthesis and evaluation these compounds. Unfortunately, these two compounds lost their activity in the enzyme inhibition assay. This might arise from the increased volumes of compounds 3a and 3b which no longer fit into the enzyme pocket. Being the end product of cholesterol degradation, estrogens are small in size. Correspondingly, the aromatase active pocket is only 400 Å3, considerably smaller compared to other CYP 450 enzymes which normally have an active site of about 530 Å3.25 The volumes for AI clinical drugs and aromatase natural substrates are in the range of 254.5–285.7 Å3. Compounds 3a and 3b have significantly larger volumes (380.1 and 356.4 Å3, respectively), which might render them too sterically bulky to fit into the aromatase active site. The best docking score for compound 3a was only 40.0 kJ/mol, indicating its poor binding interactions with the enzyme.

A great improvement was achieved when a methoxy group was added to compound 1e to result in compound 3c (Table 1): the LogP value increased from 1.69 to 1.71, the PSA increased from 39.2 to 48.4 Å2, the volume of this molecule increased from 201.1 to 227.6 Å3 and the risk of reproductive toxicity was reduced. More importantly, the IC50 value of bifunctionalized compound 6-methoxy-3-(pyridin-3-yl)chroman-4-one 3c (Table 1) decreased more than 2-fold when compared with its precursor 3-(pyridin-3-yl)chroman-4-one 1e. Encouraged by this discovery and our findings on fluorinated compounds, 8-fluoro-3-(pyridin-3-yl)chroman-4-one 3d and 6-fluoro-3-(pyridin-3-yl)chroman-4-one 3e were prepared and tested for their enzymatic activity. Being the most active compound in this study, isoflavanone 3e (IC50 = 0.8 μM) showed a 7-fold increase in potency when compared with its precursor 3-(pyridin-3-yl)chroman-4-one 1e (IC50 = 5.8 μM), and a 36-fold increase in potency when compared with its parent molecule 1a (IC50 = 29 μM). Coupled with its desirable physicochemical properties, predicted low toxicity profile and the beneficial effects of fluorine, compounds 3d and 3e represented a highly interesting class of potential anti-breast cancer agents.

3.3. Estrogen-dependent MCF-7 growth inhibition

Under physiological conditions, typical estrogen levels are 20–400 pM.26 Therefore, the use of a baseline level of estrogen may be more meaningful for the assessment of anti-proliferative activities of isoflavanone AIs. The estrogen used in our cell assays was β-estradiol and the concentration required to stimulate MCF-7 cell proliferation was determined to be 12 pM. Using this concentration, the cytotoxicity of selected isoflavanone AIs was tested against the human breast cancer MCF-7 cell line to estimate their IC50 values. The investigation of the antiproliferative effect on human breast cancer cells showed interesting cytotoxic activity of some isoflavanone compounds such as 1d, 1e and 3d. For monofunctionalized isoflavanones, these results are mostly in agreement with their aromatase inhibitory potencies, even though the IC50 values for their cytotoxic effects are about 2 to 7 times higher than their aromatase inhibitory potencies. For bifunctionalized isoflavanones, the results were more complicated, likely due to the inclusion of more factors in the cell assays and in the substrate structure. The cellular anti-cancer activity of these new AIs may be at least in part due to the aromatase inhibition, though other mechanisms might also be possible.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, we have described the synthesis and biological evaluation of two subsets of isoflavanone AIs: fluorinated isoflavanones and bifunctionalized isoflavanones. Fluorine substituents on the isoflavanone scaffold might enhance the hydrogen bonding, heme iron coordination and/or hydrophobic interactions between aromatase and its inhibitor. The proper choice and installation of a second functional group on the isoflavanone could improve the physicochemical properties and bioactivities of isoflavanone AIs. These new AIs exhibited aromatase inhibition, cellular anti-cancer activity and desirable drug-like properties. Therefore, isoflavanone AIs appear as interesting candidates for future investigation of their effects to reduce cancer cell proliferation in hormone dependent breast cancer.

5. Experimental

5.1. Chemistry

Reagents and solvents were obtained from Aldrich and used without further purification unless otherwise noted. Toluene was freshly distilled from CaH2 prior to use. The microwave-assisted reactions were conducted on a single-mode Discover System from CEM Corporation. Power cooling was turned off manually during the reaction to ensure that the reaction temperature reached 200 °C. Thin-layer chromatography was performed using pre-coated silica gel F254 plates (Whatman). Column chromatography was performed using pre-packed RediSep Rf Silica columns on a CombiFlash Rf Flash Chromatography system (Teledyne Isco). NMR spectra were obtained on a Joel 500 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts were reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to the tetramethylsilane (TMS) signal at 0.00 ppm. Coupling constants, J, were reported in Hertz (Hz). The peak patterns were indicated as follows: s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; dt, doublet of triplet; dd, doublet of doublet; m, multiplet; q, quartet. Analytical reverse-phase HPLC was carried out using a system consisting of a 1525 binary HPLC pump and 2996 photodiode array detector (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). A Nova-Pak C18 column (4 μm, 3.9 × 150 mm), also from Waters, was used with a mobile phase of methanol and water (60:40, vol./vol.) plus 0.25% acetic acid, flow rate 1.2 mL/min and UV detection wavelength at 250 nm. Control and data acquisition was done using the Empower 2 software (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). Synthesized compounds were prepared in methanol to make 1.0 mg/mL stock solutions and 10 μL of solution was injected for the HPLC test. The purity of all the compounds was assessed by HPLC at 254 nm. All final compounds were confirmed to be ≥95% purity by analysis of their peak area. Mass spectra were obtained on a Waters TQD Tandem Quadrapole Mass Spectrometer, and data was collected in electrospray positive mode (ESI+). High resolution mass spectra were recorded on a Micromass Q-TOF 2 or a Thermo Scientific LTQ-FT™ mass spectrometer operating in electrospray (ES) mode. Calculation of important physicochemical properties (logP, number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors and polar surface area) was performed using Molinspiration Cheminformatics software at URL http://www.molinspiration.com. Prediction of mutagenic, tumorigenic, irritating and reproductive toxicities and drug score was achieved utilizing OSIRIS Property Explorer software at URL http://www.organic-chemistry.org/prog/peo/.

5.1.1. General procedure for isoflavanone synthesis

The microwave-assisted isoflavanone syntheses were conducted on a single-mode Discover System from CEM Corporation. To an oven-dried standard microwave reaction vial (capacity 10 mL) equipped with a stirring bar was added AuCN (0.05 mmol, 0.05 equiv, 11.0 mg), Bu3P (0.25 mmol, 0.25 equiv, 61.7 μL), aldehyde (1 mmol, 1 equiv), alkyne (3 mmol, 3 equiv) and 1 mL of freshly distilled toluene. The reaction vial was then sealed with a Teflon septum cap, and the sample was subjected to microwave irradiation at a power of 200W for 10 min (hold time) at 200 °C. After being cooled down, the vial was opened, and the crude mixture was loaded directly on silica gel and was purified by Medium Performance Liquid Chromatography eluding with an ethyl acetate/hexanes gradient to afford the desired products.

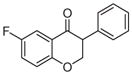

5.1.1.1. 6-Fluoro-3-phenylchroman-4-one (2a)9

Synthesized from 5-fluorosalicylaldehyde (0.5 mmol, 1 equiv, 70.1 mg), and phenylacetylene (1.5 mmol, 3 equiv, 164.7 μL) according to the general procedure for the synthesis of isoflavanone derivatives described above. Light yellow solid. Yield: 21.7%. Purity: 99.5%. Rf = 0.43 (10% EtOAc/Hex). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, ppm): δ 7.60 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.38-7.20 (m, 6H), 7.00 (dd, J = 9.2, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 4.65 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.99 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): δ 191.5, 158.2, 156.4, 134.7, 129.0, 128.6, 128.0, 123.7, 121.5, 119.7, 112.7, 71.7, 52.2. HRMS Calculated for C15H11O2FNa [M+Na] 265.0641, found 265.0631.

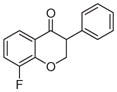

5.1.1.2. 8-Fluoro-3-phenylchroman-4-one (2b)

Synthesized from 3-fluorosalicylaldehyde (0.5 mmol, 1 equiv, 70.1 mg) and phenylacetylene (1.5 mmol, 3 equiv, 164.7 μL) according to the general procedure for the synthesis of isoflavanone derivatives described above. Orange yellow solid. Yield: 21.5%. Purity: 99.2%. Rf = 0.32 (10% EtOAc/Hex). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, ppm): δ 7.72 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.37–7.25 (m, 6H), 6.99–6.95 (m, 1H), 4.76 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.04 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): δ 191.2, 150.7, 134.4, 129.1, 128.6, 128.1, 123.1, 122.8, 121.9, 121.8, 121.1, 72.1, 52.3. HRMS Calculated for C15H11O2FNa [M+Na] 265.0641, found 265.0630.

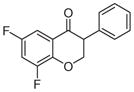

5.1.1.3. 6,8-Difluoro-3-phenylchroman-4-one (2c)

Synthesized from 3,5-difluorosalicylaldehyde (0.5 mmol, 1 equiv, 80.8 mg) and phenylacetylene (1.5 mmol, 3 equiv, 164.7 μL) according to the general procedure for the synthesis of isoflavanone derivatives described above. Orange solid. Yield: 30.9%. Purity: 98.9%. Rf = 0.31 (10% EtOAc/Hex). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, ppm): δ 7.46–7.21 (m, 7H), 4.76 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 4.05 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): δ 190.3, 134.0, 129.1, 128.6, 128.2, 111.2, 111.0, 110.8, 108.1, 107.9, 72.2, 52.3. HRMS Calculated for C15H10O2F [M−H] 259.0571, found 259.0580.

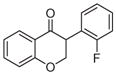

5.1.1.4. 3-(2-Fluorophenyl)chroman-4-one (2d)

Synthesized from 1-ethynyl-2-fluorobenzene (1 mmol, 1 equiv, 113.3 μL) and salicylaldehyde (3 mmol, 3 equiv, 314.2 μL) according to the general procedure for the synthesis of isoflavanone derivatives described above. White solid. Yield: 25.1%. Purity: 98.4%. Rf = 0.45 (10% EtOAc/Hex). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, ppm): δ 7.99 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.32–7.02 (m, 6H), 4.65–4.58 (m, 2H), 4.33 (dd, J = 10.5, 6.9 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): δ 191.2, 161.8, 161.2 (d, J = 245 Hz), 136.2, 130.7, 129.7, 127.8, 124.6, 122.1, 121.8, 117.9, 116.0, 115.8, 70.7, 47.6. HRMS Calculated for C15H11O2FNa [M+Na] 265.0641, found 265.0630.

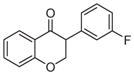

5.1.1.5. 3-(3-Fluorophenyl)chroman-4-one (2e)

Synthesized from salicylaldehyde (1 mmol, 1 equiv, 105μL) and 1-ethynyl-2-fluorobenzene (3 mmol, 3 equiv, 340 μL) according to the general procedure for the synthesis of isoflavanone derivatives described above. Light yellow, flakey solid. Yield: 30.5%. Purity: 96.9%. Rf = 0.41 (10% EtOAc/Hex). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, ppm): δ 7.95 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (m, 1H), 7.08–7.00 (m, 5H), 4.67 (d, J = 3.65 Hz, 2H), 3.99 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): δ 191.4, 163.9, 161.5, 137.4, 136.3, 130.4, 127.9, 124.4, 121.9, 120.9, 118.0, 115.8, 115.0, 71.2, 52.0. HRMS Calculated for C15H11O2FNa [M+Na] 265.06353, found 265.06357.

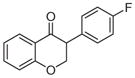

5.1.1.6. 3-(4-Fluorophenyl)chroman-4-one (2f)

Synthesized from 1-ethynyl-4-fluorobenzene (1 mmol, 1 equiv, 114.4 μL) and salicylaldehyde (3 mmol, 3 equiv, 314.2 μL) according to the general procedure for the synthesis of isoflavanone derivatives described above. Yellow solid. Yield: 28.3%. Purity: 99.5%. Rf = 0.38 (10% EtOAc/Hex). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, ppm): δ 7.95 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (t, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.26–7.23 (m, 2H), 7.06-7.00 (m, 4H), 4.64 (m, 2H), 3.97 (dd, J = 9.2, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): δ 192.0, 161.6, 136.3, 130.3, 130.2, 127.8, 121.8, 120.9, 117.9, 116.0, 115.8, 71.5, 51.6. HRMS Calculated for C15H11O2FNa [M+Na] 265.0641, found 265.0630.

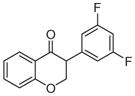

5.1.1.7. 3-(3,5-Difluorophenyl)chroman-4-one (2g)

Synthesized from 1-ethynyl-3,5-difluorobenzene (1 mmol, 1 equiv, 118.8 μL) and salicylaldehyde (3 mmol, 3 equiv, 314.2 μL) according to the general procedure for the synthesis of isoflavanone derivatives described above. A light yellow solid was formed from this reaction. Yield: 35.8%. Purity: 96.8%. Rf = 0.43 (10% EtOAc/Hex). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, ppm): δ 7.94 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.08–6.74 (m, 5H), 4.70–4.62 (m, 2H), 3.82 (dd, J = 8.3, 5.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): δ 190.7, 161.5, 136.5, 127.9, 122.0, 120.7, 118.0, 111.8, 111.6, 103.7, 103.5, 70.8, 51.7. HRMS Calculated for C15H10O2F [M−H] 259.0571, found 259.0568.

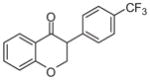

5.1.1.8. 3-(4-(Trifluoromethyl)phenyl)chroman-4-one (2h)27

Synthesized from salicylaldehyde (1 mmol, 1 equiv, 104.7 μL), and 1-ethynyl-4-trifluoromethylbenzene (3 mmol, 3 equiv, 489.4 μL) according to the general procedure for the synthesis of isoflavanone derivatives described above. Light yellow solid. Yield: 19.6%. Purity: 97.5%. Rf = 0.37 (10% EtOAc/Hex). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, ppm): δ 7.95 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.52 (t, J = 8.3, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.3, 2H), 7.00–7.08 (m, 2H), 4.68 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 4.06 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): δ 191.4, 161.6, 139.1, 136.5, 129.1, 127.9, 125.9, 121.9, 120.9, 118.0, 71.1, 52.1, 13.6. HRMS Calculated for C16H11O2F3Na [M+Na] 315.0609, found 315.0604

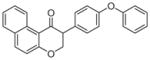

5.1.1.9. 2-(4-Phenoxyphenyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-benzo[f]chromen-1-one (3a)

Synthesized from 2-hydroxy-1-naphthaldehyde (0.4 mmol, 1 equiv, 68.9 mg) and 1-ethynyl-4-phenoxybenzene (1.2 mmol, 3 equiv, 217 μL) according to the general procedure for the synthesis of isoflavanone derivatives described above. White solid. Yield: 35.1%. Purity: 98.5%. Rf = 0.39 (10% EtOAc/Hex). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, ppm): δ 9.49 (dd, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (dd, J = 8.7, 1H), 7.25–7.65 (m, 4H), 6.98–7.15 (m, 2H), 4.79 (m, 2H), 4.04 (dd, J = 7.8, 4.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): δ 193.3, 163.6, 157.0, 137.8, 131.9, 130.3, 129.9, 129.8, 129.4, 128.6, 126.1, 125.0, 123.5, 119.2, 119.0, 118.7, 71.3, 52.3. HRMS Calculated for C25H18O3Na [M+Na] 389.1154, found 389.1140.

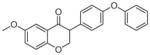

5.1.1.10. 6-Methoxy-3-(4-phenoxyphenyl)chroman-4-one (3b)

Synthesized from 2-hydroxy-5-methoxybenzaldehyde (0.4 mmol, 1 equiv, 49.8 μL), and 1-ethynyl-4-phenoxybenzene( 1.2 mmol, 3 equiv, 217.04 μL) according to the general procedure described above. Light yellow solid. Yield 36.3%. Rf = 0.30 (10% EtOAc/Hex). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, ppm): δ 7.37 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 7.23 (t, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.10–7.12 (m, 2H), 6.94–7.02 (m, 5H), 4.57–4.64 (m, 2H), 3.96 (dd, J = 8.25, 5.05 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): δ 192.3, 157.0, 156.3, 154.4, 130.0, 129.9, 125.5, 123.7, 119.3, 119.2, 119.1, 108.1, 71.8, 55.9, 51.7.

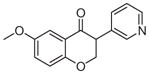

5.1.1.11. 6-methoxy-3-(pyridin-3-yl)chroman-4-one (3c)

Synthesized from 2-hydroxy-5-methoxybenzaldehyde (1 mmol, 1 equiv, 136.04 μL), and 3-ethynylpyridine (3 mmol, 3 equiv, 309.3 mg) according to the general procedure for the synthesis of isoflavanone derivatives described above. Light yellow solid. Yield: 26.9%. Purity: 98.2%. Rf = 0.28 (40% EtOAc/Hex). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, ppm): δ 8.55 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.57–7.59 (m, 1H), 7.34 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 7.25–7.29 (m, 1H), 7.13 (dd, J = 8.7, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 4.59–4.64(m, 2H), 3.98 (dd, J = 9.2, 5 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): δ 191.2, 156.3, 154.5, 149.9, 149.2, 136.1, 131.1, 125.8, 123.7, 120.6, 119.3, 107.9, 71.3, 55.9, 49.9. HRMS Calculated for C15H13O3NNa [M+Na] 256.0974, found 256.0967.

5.1.1.12. 8-Fluoro-3-(pyridin-3-yl)chroman-4-one (3d)

Synthesized from 3-fluorosalicylaldehyde (1.0 mmol, 1 equiv, 140.1 mg) and 3-ethynylpyridine (3 mmol, 3 equiv, 309.4 mg) according to the general procedure for the synthesis of isoflavanone derivatives described above. Light yellow solid. Yield: 23.3%. Purity: 99.5%. Rf = 0.40 (60% EtOAc/Hex). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, ppm): δ 8.55–8.53 (m, J = 2.3, 2H), δ 7.70 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 6.2, 1H), 7.33–7.26 (m, 2H), 6.99–6.95 (m, 1H), 4.76–4.70 (m, 2H), 4.08–4.06 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): δ 190.2, 152.7, 150.6, 149.9, 149.4, 136.3, 130.3, 123.9, 122.8, 122.4, 122.2, 121.4, 71.6, 49.9. HRMS Calculated for C14H11FNO2 [M+H] 244.0781, found 244.0774.

5.1.1.13. 6-Fluoro-3-(pyridin-3-yl)chroman-4-one (3e)

Synthesized from 5-fluororsalicylaldehyde (0.5 mmol, 1 equiv, 70.1 mg) and 3-ethynylpyridine (1.5 mmol, 3 equiv, 154.7 mg) according to the general procedure for the synthesis of isoflavanone derivatives described above. Light yellow solid. Yield: 27.4%. Purity: 99.5%. Rf = 0.21 (30% EtOAc/Hex). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, ppm): δ 8.56–8.54 (m, 2H), 7.58 (dd, J = 8.2, 2.8 Hz, 2H), 7.30–7.24 (m, 2H), 7.01 (dd, J = 9.2, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 4.66–4.62 (m, 2H), 4.01 (dd, J = 9.6, 5.0 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): δ 190.5, 157.9, 157.6, 149.9, 149.4, 136.2, 130.6, 124.1, 123.8, 121.2, 119.8, 112.7, 71.3, 49.8. HRMS Calculated for C14H11FNO2 [M+H] 244.0781, found 244.0774.

5.2. Aromatase activity assay

Inhibitory potencies of compounds were determined according to an established procedure using a commercially available aromatase test kit from BD Gentest.16 This fluorescence-based assay measures the rate at which recombinant human aromatase (baculovirus/insect cell-expressed) converts the substrate 7-methoxy-trifluoromethylcoumarin (MFC) into a fluorescent product 7-ethynyl-trifluoromethylcoumarin (HFC) (λex = 409 nm, λem = 530 nm) in a NADPH regenerating system. Briefly, concentrated stock solutions of test compounds were prepared in acetonitrile. 100 μL samples containing serial dilutions of test compounds (dilution factor of 3 between samples) and cofactor mixture (0.4 U/mL glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; 16.2 μM NADP+; 825 μMMgCl2; 825 μMglucose-6-phosphate; 50 μMcitrate buffer, pH 7.5) were prepared in a 96 well plate. After incubating the plate for 10 min at 37 °C, 100 μL of an aromatase/P450 reductase/substrate solution (105 μg protein/mL enzyme; 50 μM MFC; 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) were added to each well. The plate was covered and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. 75 μL of 0.5 M Tris base were then added to stop the reaction and the fluorescence of the formed de-methylated MFC was measured with a plate reader (SpectraMax Gemini, Molecular Devices).

Fluorescence intensities, which were proportional to the amount of reaction product generated by aromatase, were graphed as a function of inhibitor concentration and then fit to a 3-parameter logistic function. Inhibitory potencies were expressed in terms of the IC50 value, the inhibitor concentration necessary to reduce the enzyme activity by half. Each experiment was performed at least in triplicate.

5.3. Molecular modeling

The coordinates of the X-ray crystal structure of the aromatase/androstenedione complex (PDB code 3EQM) were downloaded from the Protein Databank (http://www.rcsb.org) and imported into the modeling program SYBYL (version 8.0; Tripos, St. Louis, MO). All non-protein components were deleted and hydrogen atoms were added to the protein structure. Partial charges were assigned according to the Amber library and the positions of the added hydrogen atoms were optimized by molecular mechanics minimization that kept the positions of the heavy atoms static.28 The energy minimization was performed with the Powell method in combination with the Amber7 FF99 force field, a distance-dependent dielectric constant of 4, and a convergence criterion of 0.05 kcal/(mol Å). The molecular structures of inhibitors were also prepared in SYBYL and the conformational energy of each structure was minimized by molecular mechanics (MMFF94s force field, MMFF94 charges, and distance-dependent dielectric constant of 4) using the conjugate gradient method and a termination criterion of 0.01 kcal/(mol Å).

Inhibitor structures were computationally docked into the enzyme’s binding site using the program GOLD (version 5.0.1; CCDC, Cambridge, UK). GOLD operates with a genetic search algorithm and allows for complete ligand and partial binding site flexibility.29 The scoring function GoldScore was used and the size and center of the docking sphere were as reported before.9 The settings for the genetic algorithm runs were kept at their default values (population size: 100, selection pressure: 1.1; number of operations: 100,000, the number of islands: 5, niche size: 2, probability for migration, mutation, and crossover: 10%, 95%, and 95%, respectively). For each ligand, 30 runs were performed under identical conditions.

5.4. Cell assay

MCF-7 cells were obtained from the NCI-Federick national lab. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 0.01 mg/ml insulin and 10 nM β-estradiol (Sigma). Assays were accomplished by seeding cells at a density of 15,000 cells/well in a 24 well plate and incubated at 37 °C overnight. Then cells were treated for 72 h with indicated concentrations of freshly dissolved compounds. The medium containing compounds was discarded; fresh medium containing 20 μL of MTT (5 mg/ml) was added to each well and incubated for an additional 4 h. The medium was removed after adding 500 μL of DMSO to each well the optical densities at 570 nm were determined. The IC50 values were calculated using Kaleida-Graph(Synergy Software, USA) software.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P20GM103436. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study was also supported by the Center for Integrative Science and Mathematics (CINSAM) and Northern Kentucky University Office of Research, Grants and Contracts Seed Grant. We thank Dr. Grant Edwards for his help with the HPLC and Dr. Isabelle Lagadic for the assistance with the microwave reactor.

Abbreviations

- Arg 115

arginine 115

- Ile 133

isoleucine 133

- Phe 221

phenylalanine 221

- Trp 224

tryptophan 224

- Asp 309

aspartic acid 309

- Thr 310

threonine 310

- Val 370

valine 370

- Leu 477

leucine 477

- CYP19

cytochrome P450 aromatase

- AIs

aromatase inhibitors

- SERMs

selective estrogen receptor modulators

- NSAIs

non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- MS

mass spectrometry

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

Footnotes

Abbreviations used for amino acids and designation of peptides follow the rules of the IUPACIUB Commission of Biochemical Nomenclature in J. Biol. Chem. 1972, 247, 977–983.

References and notes

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2013. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray J, Evans N, Taylor B, Rizzo J, Walker M. Int J Occ Environ Health. 2009;15:43. doi: 10.1179/107735209799449761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Muftuoglu Y, Mustata G. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:3050. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.03.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Recanatini M, Cavalli A, Valenti P. Med Res Rev. 2002;22:282. doi: 10.1002/med.10010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brueggemeier RW, Hackett JC, Diaz-Cruz ES. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:331. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furr BJA. Milestones in Drug Therapy. Aromatase Inhibitors. 2. Birkhauser; 2006. p. 182. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christodoulou MS, Fokialakis N, Passarella D, Garcia-Argaez AN, Gia OM, Pongratz I, Dalla Via L, Haroutounian SA. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:4120. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ibrahim AR, Abul-Hajj YJ. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1990;37:257. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(90)90335-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brueggemeier RW, Richards JA, Joomprabutra S, Bhat AS, Whetstone JL. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;79:75. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonfield K, Amato E, Bankemper T, Agard H, Steller J, Keeler JM, Roy D, McCallum A, Paula S, Ma L. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:2603. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purser S, Moore PR, Swallow S, Gouverneur V. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:320. doi: 10.1039/b610213c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou P, Zou J, Tian F, Shang Z. J Chem Inf Model. 2009;49:2344. doi: 10.1021/ci9002393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meanwell NA. J Med Chem. 2011;54:2529. doi: 10.1021/jm1013693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Smart BE. J Fluorine Chem. 2001;109:3. [Google Scholar]; (b) Banks Ronald Eric, Smart BE, Tatlow JC. Organofluorine Chemistry: Principles and Commercial Applications. 1. Springer; 1994. p. 669. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahuja R, Samuelson AG. Cryst Eng Commun. 2003;5:395. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagmann WK. J Med Chem. 2008;51:4359. doi: 10.1021/jm800219f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Maiti A, Reddy PVN, Sturdy M, Marler L, Pegan SD, Mesecar AD, Pezzuto JM, Cushman M. J Med Chem. 2009;52:1873. doi: 10.1021/jm801335z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stresser DM, Turner SD, McNamara J, Stocker P, Miller VP, Crespi CL, Patten CJ. Anal Biochem. 2000;284:427. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) [accessed 6-6-2013];Molinspiration. http://www.molinspiration.com/cgi-bin/properties.; (b) [accessed 6-6-2013];OSIRIS Property Explorer. http://www.organicchemistry.org/prog/peo/

- 18.(a) Bell-Horwath TR, Vadukoot AK, Thowfeik FS, Li G, Wunderlich M, Mulloy JC, Merino EJ. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:2951. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jones AR, Bell-Horwath TR, Li G, Rollmann SM, Merino EJ. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:2542. doi: 10.1021/tx300337j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Li G, Bell T, Merino EJ. Chem Med Chem. 2011;6:869. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Welshons WV, Craig Jordan V. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23:1935. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(87)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Le Bail JC, Varnat F, Nicolas JC, Habrioux G. Cancer Lett. 1998;130:209. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kijima I, Itoh T, Chen S. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97:360. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitropoulou TN, Tzanakakis GN, Kletsas D, Kalofonos HP, Karamanos NK. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:155. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghosh D, Griswold J, Erman M, Pangborn W. Nature. 2009;457:219. doi: 10.1038/nature07614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerns EH, Di L. Drug-like Properties: Concepts, Structure Design and Methods. from ADME to Toxicity Optimization. 2. Elsevier Inc; 2008. p. 552. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Namazian M, Coote ML. J Fluorine Chem. 2009;130:621. [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Rowland P, Blaney FE, Smyth MG, Jones JJ, Leydon VR, Oxbrow AK, Lewis CJ, Tennant MG, Modi S, Eggleston DS, Chenery RJ, Bridges AM. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511232200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Williams PA, Cosme J, Vinković DM, Ward A, Angove HC, Day PJ, Vonrhein C, Tickle IJ, Jhoti H. Science. 2004;305:683. doi: 10.1126/science.1099736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imhof M, Molzer S. Toxicol In Vitro. 2008;22:1452. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Bellina F, Masini T, Rossi R. Eur J Org Chem. 2010;2010:1339. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lessi M, Masini T, Nucara L, Bellina F, Rossi R. Adv Synth Catal. 2011;353:501. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paula S, Ball WJ., Jr Proteins. 2004;56:595. doi: 10.1002/prot.20105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Jones G, Willett P, Glen RC. J Mol Biol. 1995;245:43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(95)80037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jones G, Willett P, Glen RC, Leach AR, Taylor R. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:727. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]