Abstract

Wogonin is a one of the bioactive compounds of Scutellaria baicalensi Georgi which has been shown to have antiinflammatory, anticancer, antiviral and neuroprotective effects. However, the underlying mecha-nisms by which wogonin induces apoptosis in cancer cells still remain speculative. Here we investigated the potential activation of MAPKs and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by wogonin on MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. These results showed that wogonin induced mitochondria and death-receptor-mediated apoptotic cell death, which was characterized by activation of several caspases, induction of PARP cleavage, change of antiapoptotic/pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member ratios and cleavage of Bid. We also found that generation of ROS was an important mediator in wogonin-induced apoptosis. Further investigation revealed that wogonin activated ERK and p38 MAPKs, which was inhibited by N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), a ROS scavenger, indicating that wogonin-induced ROS are associated with MAPKs activation. These data demonstrate that wogonin may be a novel anticancer agent for treatment of breast cancer.

Keywords: apoptosis, breast cancer, mitogen-activated protein kinases, reactive oxygen species, wogonin

INTRODUCTION

Flavonoids belong to a chemical class of polyphenolic compounds that are present in all vascular plants. They have been reported to exhibit a variety of beneficial effects, including antioxidant, antiinflammatory, antiviral, antitumor and antiallergic activities (Fresco et al., 2006; Ramos, 2007), resulting in a search for dietary flavonoids with novel therapeutic effects.

Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi has been widely used for the treatment of hyperlipemia, atherosclerosis, hypertension, dysentery, and inflammatory diseases such as atopic dermatitis. One of the bioactive compounds in Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi is Wogonin (5,7-dihydroxy-8-methoxyflavanone). Wogonin, a monoflavonoid, has been shown to have antiinflammatory, antiviral and neuroprotective effects (Chi et al., 2003; Enomoto et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2003; Ma et al., 2002; Tai et al., 2005). The anti-inflammatory activity of wogonin likely involves suppression of iNOS induction and COX-2 expression. Consequently, nitric oxide synthesis and prosta-glandin E2 production are inhibited (Chen et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2001). In addition, it has been reported that wogonin pos-esses anticancer activities in several cancer cells, including myelogenous leukemia cells (Lee et al., 2002), hepatomacellular carcinoma cells (Wang et al., 2006a), breast cancer cells (Chung et al., 2008), murine sacrcoma S 180 cells (Wang et al., 2006b) and bladder cancer cells (Ikemoto et al., 2000). Interestingly, wogonin has no effect on inducing apoptosis in PBMCs and fibroblasts (Liu et al., 2002). On the other hand, a number of studies have demonstrated the therapeutic potential of wogonin against other carcinoma cells, but its mechanism of action remains to be elucidated.

Here we provide evidence that wogonin induced apoptosis in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells by generation of ROS and activation of MAPK signaling pathways

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Wogonin was purchased from Wako Pure Chemicals (Japan). Wogonin was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a maximum concentration of 0.1%. Minimum Essential Medium (MEM), Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS), fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomycin, sodium pyruvate and trypsin-EDTA were purchased from WelGENE (Deagu, Korea). Insulin was purchased from Gibco-BRL (USA). MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide], N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) and DMOS were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). The 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), the JNK inhibitor (SP600125) and a p38 inhibitor (SB203580) were purchased from Calbiochem (USA). An ERK inhibitor (U0126), β-actin, caspase 8, caspase 9, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) antibodies, the MAPK family antibody sampler kit, and the phospho-MAPK family antibody sampler kit were purchased from Cell signaling (USA). Bcl-2 and Bax antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (USA).

Cell lines and cell culture

The human breast cancer cell line, MCF-7, was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA). The cells were maintained in MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 0.01 mg/ml insulin. Cultures were routinely maintained at 37℃ in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Determination of cytotoxicity

The effect of drugs on the proliferation rate/cytotoxicity of MCF-7 cells was assessed by using a colorimetric (MTT) assay. Briefly, cells were grown in 96-well flat-bottomed plates in media with 10% FBS allowed attach overnight. Then media was removed and replaced with fresh media with varying concentrations of drug. At the end of the treatment, medium was replaced with an MTT (2.5 mg/ml) solution and cells were incubated at 37℃. Following 4 h of incubation, MTT solution was discarded and the resulting formazan crystal was solubilized with DMSO. The optical densities were measured at 570 nm and results were calculated as a percentage of unexposed control.

Flow cytometry analysis of apoptotic cells

Apoptotic cells were quantified by Annexin V and PI double staining using a kit purchased from BD biosciences (USA). MCF-7 cells exposed to various concentrations of drugs were harvested by trypsinization and washed twice with cold PBS. The cells were resuspended in 1× binding buffer at a concen-tration of 106 cells/ml and 200 μ cell suspensions were stained with 5 μl of an Annexin V-FITC solution and 5 μl of a PI solution for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Fluorescence was analyzed on a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences, USA). Cells that were FITC+/PI- were considered to be apoptotic cells.

Western blot analysis

After treatment with wogonin, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, harvested, and lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0] with 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, USA). After centrifugation, the supernatant was separated and stored at -70℃ until use. Protein concentrations were quantified by using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, USA). Equal amounts of pro- tein were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene diflu-oride membrane. The membrane was blocked and incubated with primary antibody overnight in Tris-buffered saline with 0.2% Tween-20 and 2.5% nonfat dry milk (or 2.5% bovine serum albumin). Following three washes for 10 min with Tris-buffered saline with 0.2% Tween-20, blots were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. The blots were washed again three times in Tris-buffered saline with 0.2% Tween-20 and visualized with an ECL advance detection system.

Determination of caspase 9 activity

The enzymatic activity of caspase 9 was evaluated by using a colorimetric assay kit (Millipore, USA) according to the protocol provided by manufacturer. It is based on the spectrophotometric detection of the chromophore p-nitroaniline (pNA) after cleavage from an enzyme substrate of caspase 9, LEHD- pNA. MCF-7 cells were seeded in 6 well plates at 5 ×105 cells/well and then incubated with chemicals for 24 h. Floating cells and attached cells were collected, centrifuged and washed with cold PBS twice. Cells were pelleted, and lysed in the provided buffer and incubated on ice for 10 min. Lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4℃, and protein content was measured by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, USA). The supernatant was incubated with the caspase 9 substrate in assay buffer for 2 h at 37℃. The optical density of the release of pNA was quantified spectrophotometrically at 405 nm.

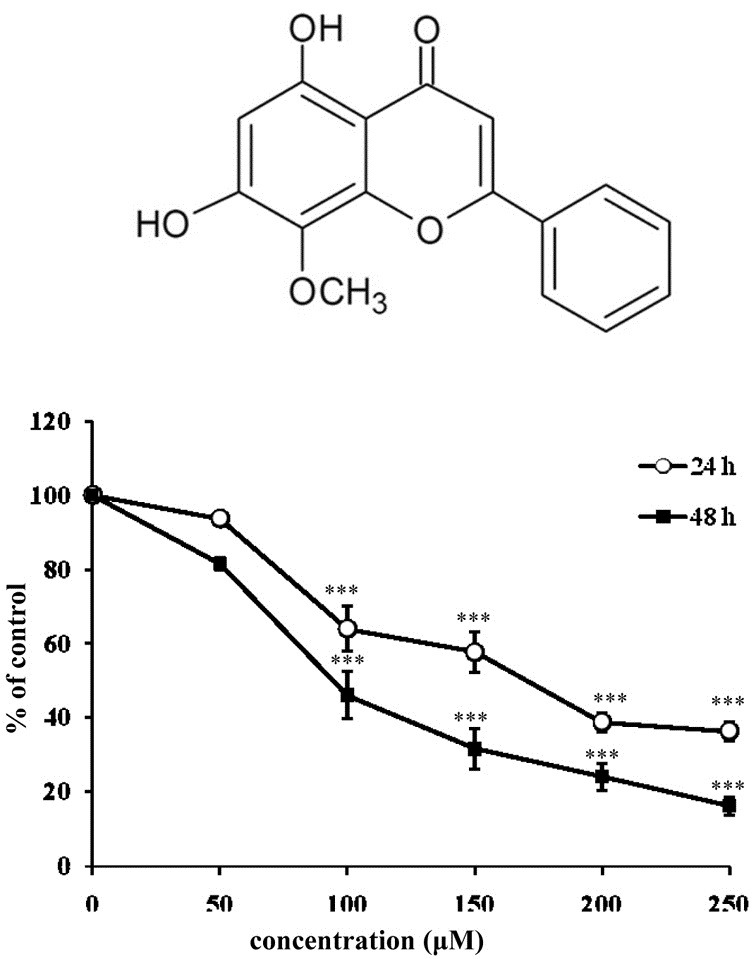

Fig. 1. The effects of wogonin on inhibition of cell proliferation in breast cancer MCF-7 cells. (A) Chemical structure of wogonin (B) Cell viability was analyzed using the MTT assay as described in the “Materials and Methods”. Cells were incubated with wogonin at the concentrations indi-cated for 24 and 48 h. Viability was calculated as the percent of control. The bars represent the mean values ± SD triplicate (n = 3). ***P < 0.001 versus control values.

Measurement of intracellular ROS levels

The 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) was used to monitor the intracellular ROS levels. Cells were plated in 96 well plates at a density of 5 × 105 and exposed to varying concentrations of drug. DCFH-DA was added to drug-treated cells at a final concentration of 5 μM and cells were incubated for 30 min at 37℃. Fluorescence intensity was measured using a Cytofluor 2350 plate reader (Millipore, USA) at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were done independently at least three times and values were expressed as means ± SD. Significant differences between groups were analyzed by using a repeated-measure ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Wogonin inhibits cell proliferation in human breast cancer cells in a concentration- and time-dependent manner

The overall cytotoxic effect of wogonin in breast cancer cells was assessed using an MTT assay. As shown in Fig. 1B, wogonin inhibited cell proliferation in a concentration- and time-dependent manner when compared to the control. At the highest concentration, cell viability after 48 h of treatment was inhibited 84% compared to untreated cells. Because the IC50 was around 100 μM after wogonin treatment for 48 h, we used wogonin ranging between 50-200 μM in future assessments.

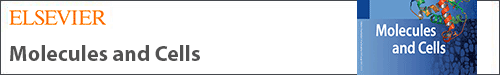

Wogonin induces apoptosis in human breast cancer cells

To determine whether wogonin-induced cell death involved apoptosis, we next investigated the extent of apoptosis by flow cytometry analysis, using double staining with Annexin-V and PI. Quantitative evaluation by flow cytometry showed that treatment of MCF-7 cells with wogonin increased the percentages of apoptotic cells as compared with untreated control cells (Fig. 2A). It was observed that treatment with wogonin increased the number of apoptotic cells from 0% to 21.7% in a dose-dependent manner.

Fig. 2. Wogonin induces apoptotic cell death. (A) Determination of apoptosis by flow cytometry. Flow cytometric analysis was carried out by using Annexin V-FITC and PI double-staining on MCF-7 cells treated with or without wogonin at the concentrations indicated for 48 h. The bars represent the percentage of apoptotic cells after treatment as indicated. The bars represent the mean values ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 versus control values. (B) Degradation of procaspase 9, procaspase 8 and PARP in wogonin-treated MCF-7 cells. Cells were treated with wogonin for 48 h. Cell lysates were then examined by Western blot analysis to verify the activation of caspases and PARP. Band intensities were normalized to β-actin and presented as a bar graph. The bars represent the mean values ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 versus control values. (C) Western blot analysis of Bcl-2 family members including Bcl-2, Bax and Bid in wogonin-treated MCF-7 cells. Cells were treated with wogonin for 48 h. Cell lysates were then examined by Western blot analysis to verify the activation of Bcl-2 family members. Band intensities were normalized to β-actin and presented as a bar graph. The bars represent the mean values ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 versus control values. (D) Wogonin activated cas-pase 9 in MCF-7 cells. The cells were incubated with wogonin for 48 h. After adding assay buffer and LEHD-pNA, the samples were incubated at 37℃ for 1 h. The OD of the samples was read at 405 nm. Relative caspase 9 activity was compared to non-treated controls. The bars represent the mean values ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Next, the effect of wogonin on caspases which are crucial mediators in the apoptotic pathways was investigated. Examination of caspase activation in wogonin-treated MCF-7 cells showed that caspase 9 was activated in a concentration-depen-dent fashion, similarly to PARP cleavage (Fig. 2B).

Wogonin induces apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway in human breast cancer cells

To examine the mitochondrial apoptotic events associated with wogonin-induced apoptosis, we analyzed the alteration in Bcl-2 family proteins and caspase 9 activity. The results from immunoblot analysis showed that wogonin treatment changed the proapop-totic/antiapoptotic Bcl-2 ratio through increased Bax and decreased Bcl-2 protein levels (Fig. 2C). In addition, we measured caspase 9 activity, an initiator caspase in the mitochondrial pathway, using a colorimetric assay kit. As shown in Fig. 2D, treatment of MCF-7 cells with wogonin increased caspase 9 activities. Cells treated with Wogonin at 200 μM showed 6.1-fold higher activities when com-pared to untreated cells. These observations suggest that wogonin-induced apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway.

Wogonin-induced apoptosis related with caspase 8 and Bid activation

To investigate the possibility wogonin-induced apoptosis was associated with death receptor pathway, we examined caspase 8 and Bid activation. Caspase 8 is one of the initiator caspases in the death receptor pathway of apoptosis. Activation of caspase 8 leads to cleavage of Bid (Hengartner, 2000). As shown in Figs. 2B and 2C, wogonin treatment reduced the level of procaspase 8 and Bid in a concentration-dependent manner. These data suggest possible activation of the death receptor pathway as a possible mechanism of action by wogonin on MCF-7 cells.

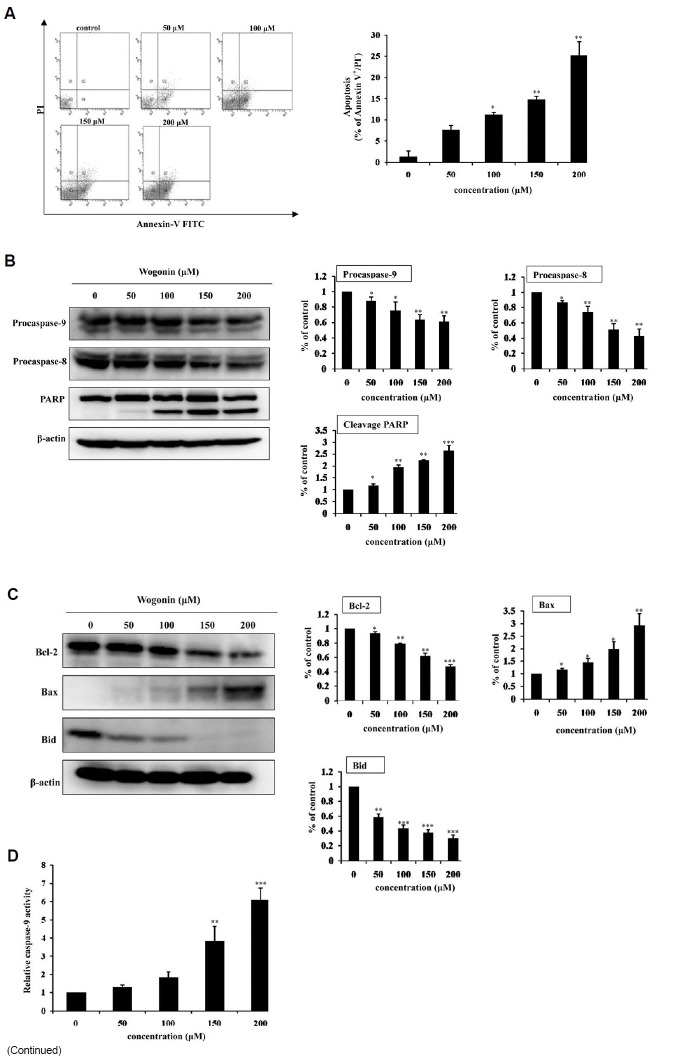

Wogonin triggers ROS generation

In aerobic organisms, ROS are produced during normal cellular function by mitochondria and various enzyme systems. There is growing evidence that ROS play a role in the early signals that modulate apoptosis. ROS levels are increased in cells exposed to various stimuli, such as anticancer drugs and UV irradiation (Benhar et al., 2002; Simon et al., 2000). To investigate whether wogonin triggers ROS generation in human breast cancer cells, we monitored the change of intracellular ROS using the oxidation-sensitive fluorescent dye, DCFH-DA. DCFH-DA-based assays revealed that intracellular ROS levels were elevated in MCF-7 cells following treatment with wogonin. Cells treated with wogonin at 200 μM showed a 1.5-fold higher ROS production compared to untreated cells (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. The effect of wogonin on the production of ROS. (A) The production of intracellular ROS in wogonin-treated MCF-7 cells was detected by using DCFH-DA measured with a spectrofluorometer (excitation: 485 nm; emission: 535 nm). The bars represent the mean values ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 versus control values. (B) Pretreatment with NAC reduces wogonin-generated ROS. Cells were pretreated with 5 mM of NAC for 1 h and then treated with wogonin at 200 μM. The production of intracellular ROS was detected using by DCFH-DA and measured with a spectrofluorometer (excitation: 485 nm; emission: 535 nm). The bars represent the mean values ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05 versus control values. (C) NAC attenuates wogonin-induced apoptosis. Cells were pretreated with NAC (5 mM) for 1 h, followed by woginin at 200 μM for 48 h. Flow cytometric analysis was carried out by double-staining with annexin V-FITC and PI. The bars represent the percentage of apoptotic cells. The bars represent the mean values ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05 versus control values.

ROS is involved in wogonin-induced apoptosis

We observed that the levels of intracellular ROS were elevated wogonin-treated MCF-7 cells and postulated that the generation of ROS might cause apoptotic cell death. To examine whether ROS was associated with wogonin-induced apoptosis, cells were treated with wogonin in the presence or absence of the N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), a ROS scavenger. Pretreatment of NAC decreased the generation of ROS induced by wogonin (Fig. 3B) and flow cytometric analysis showed that wogonin-induced apoptosis was attenuated in NAC pretreated-cells as compared to cells treated with wogonin alone (Fig. 3C). These findings indicate that the generation of ROS may be a mediator in wogonin-induced apoptosis.

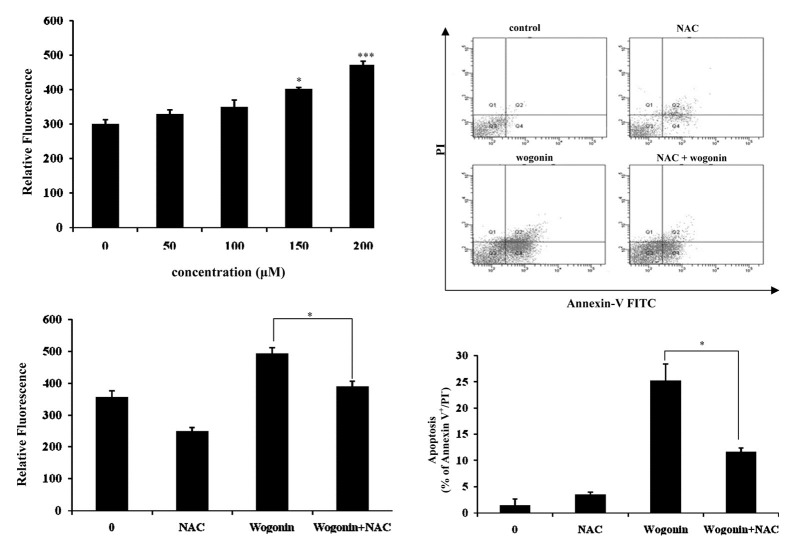

ERK and p38 signaling pathways contribute to induction of apoptosis in wogonin treatment in MCF-7

Since activated MAPKs play a critical role in apoptosis, we analyzed by immunoblotting the phosphorylation of MAPK family members including ERK, JNK and p38. As shown in Fig. 4A, treatment of wogonin increased the amount of phosphorylation of ERK and p38 in a concentration-dependent manner, while JNK was not significantly activated by wogonin treatment.

Fig. 4. Treatment of wogonin in MCF-7 cells induces activation of ERK, JNK and p38. (A) MCF-7 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of wogonin. Cell lysates were examined by Western blot analysis using antibodies to phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK), total ERK, phosphorylated JNK (p-JNK), total JNK, phosphorylated p38 (p-p38) and total p38. Western blot band intensities were normalized by each total form of MAPKs and presented as a bar graph. The bars represent the mean values ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 versus control values. (B) The effect of MAPK inhibitors on wogonin-mediated apoptosis. Cells were incubated with wogonin (200 μM) and/or pretreated with the following MAPK inhibitors: 20 μM of U0126 (ERK inhibitor), 20 uM of SB203580 (p38 inhibitor) and 10 μM of SP600125 (JNK inhibitor). Flow cytometry was performed by double-staining with Annexin V-FITC and PI. The bars represent the percentage of apoptotic cells and represent the mean values ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 versus control values. (C) Pharmacological inhibitors of MAPKs reduce phosphorylation of ERK and p38 in wogonin-treated cells. MCF-7 cells were pretreated with (i) 20 μM of U0126 (ERK inhibitor), (ii) 20 μM of SB203580 (p38 inhibitor) for 1 h before treatment with wogonin (200 μM). Cell lysates were examined by western blot analysis using antibodies to phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK), total ERK, phosphorylated p38 (p-p38) and total p38. Band intensities were normalized to each total form of MAPKs and presented as a bar graph. The bars represent the mean values ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 versus control values.

We further investigated the role of MAPKs in wogonin-media-ted apoptosis in MCF-7 breast cancer cells by employing phar-macological inhibitors of MAPKs. The data showed that phar-macological inhibitors of p38 attenuated wogonin-induced apo-ptosis and similar results were shown with an ERK inhibitor (Fig. 4C). But, a JNK inhibitor, SP600125 did not affect the extent of apoptosis in wogonin-treated cells. In addition, a selective inhibitor of ERK (U0126), and p38 (SB203580) not only blocked phosphorylation of ERK and p38 in pretreated cells but also reduced phosphorylation of ERK and p38 in wogonin-treated MCF-7 cells (Fig. 4C). These data indicate that MAPKs such as ERK and p38 play a role in wogonin-induced apoptosis.

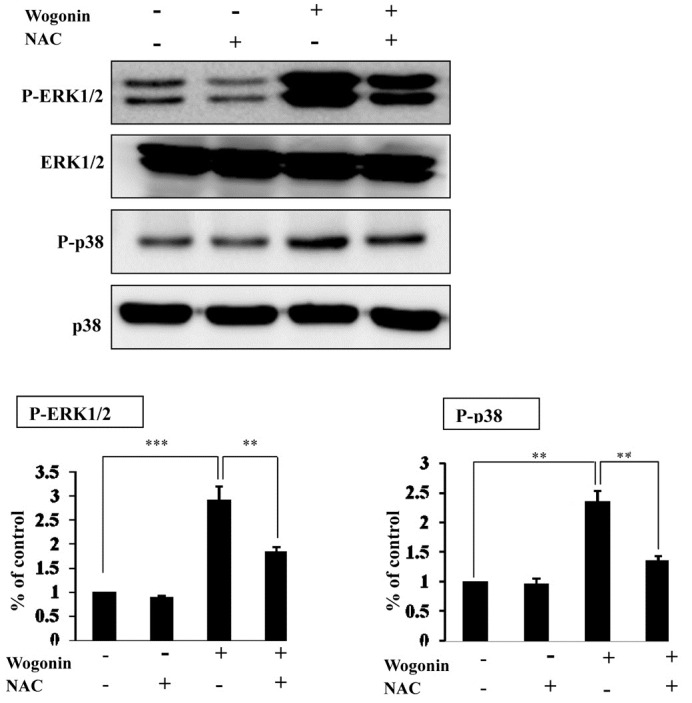

Role of ROS in wogonin-induced MAPK activation

To understand a relationship between generation of the intra-cellular ROS and activation of ERK and p38 MAPK in wogonin treatment, MCF-7 cells were treated with wogonin in the presence or absence of NAC. As shown Fig. 5, pretreatment of NAC restored wogonin-induced p38 MAPK and ERK phosphorylation as compared to wogonin treatment alone. These data suggest that ROS generation is involved in wogonin-induced MAPK activation.

Fig. 5. Treatment with NAC attenuates wogonin-activated phos-phorylation of MAPKs. Cells were pretreated with NAC (5 mM) for 1 h and then treated with wogonin (200 uM). Cell lysates were examined by Western blot analysis using antibodies to phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK), total ERK, phosphorylated p38 (p-p38) and total p38. Band intensities were normalized to each total form of MAPKs and presented as a bar graph. The bars represent the mean values ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 versus control values.

DISCUSSION

Breast cancer has the highest incidence of neoplasms in women (Jemal et al., 2009). Although several chemotherapeutic drugs have been approved for use in the treatment of breast cancer, these agents have a host of toxic side effects and acquired resistance of drugs is a major problem fielding the clinic (Arkin, 2005). Diminishing the side effects and maximizing drug efficacy are major goals in cancer treatment. Wogonin, a bioactive com-pound in Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, has attracted attention as an anticancer drug because it has less toxicity in normal cells (Liu et al., 2002) and exerts anticancer activity in several cancer cells (Ikemoto et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2006b). However, the underlying mechanisms by which wogonin induce apoptosis in cancer cells are not known. Therefore, the aim of this study was to get insight into the mechanisms associated with induction of apoptosis by wogonin. Our observations show that wogonin induce mitochondria and death-receptor-mediated apoptotic cell death, which is characterized by activation of several caspases, induction of PARP cleavage, change in the ration of antiapoptotic/proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members and cleavage of Bid.

The mitochondrial apoptotic pathway which responds to various stress stimuli such as DNA damage has been established as an important signaling event in apoptosis (Khosravi-Far and Esposti, 2004). Following the treatment of wogonin in MCF-7 cells, we detected increases of Bax and decreases in Bcl-2 expression, indicating that a change in the ratio of proapoptotic and antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members might contribute to induction of apoptosis by wogonin. Additionally, we observed that caspase 9 activity increased after treatment of wogonin. These results suggest that wogonin-induced apoptosis might also be mediated by the mitochondrial pathway. The death receptor pathway is triggered by stimuli such as Fas, tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) and TRAIL (Ghobrial et al., 2005; Stra-sser et al., 2000). Activation of the death receptor causes clea-vage of caspase 8, which interacts with mitochondrial apoptotic death pathways by cleaving Bid. In the present study, degradation of procaspase 8 and cleavage of Bid was observed. These finding indicate that apoptosis by wogonin is correlated with the death receptor apoptotic pathway.

ROS which are not only produced through a variety of cellular events, but also derived from exogenous sources, play important role in the regulation of cellular functions such as cell proliferation, differentiation and immune responses (Kamata and Hirata, 1999). However, excessive production of ROS causes oxidative stress, which contributes to adverse events including heat failure, myocardial infarction and neuronal cell death (Annunziato et al., 2003; Kumar and Jugdutt, 2003). Accumu-lating evidence suggests that the increase in oxidative stress is related with the apoptotic response induced by several anticancer agents. In addition, chemotherapeutic drugs are selectively toxic to cancer cells since human tumor cells appear to generate ROS at a far greater rate than do normal cells and push these already stressed cells beyond their limit (Schumacker, 2006). Our data demonstrate that wogonin can elevate the levels of intracellular ROS. Furthermore, we observed that blocking the increase of ROS with the antioxidant NAC resulted in decreased intracellular ROS levels as well as wogonin-induced apoptosis. These data indicate that ROS accumulation contributes to wogonin-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells.

MAPKs have been associated with regulation of cell fate though apoptosis (Wada and Penninger, 2004). These signaling pathways are activated by various stimuli such as cytokines, UV irradiation and anticancer agents. Recent studies show that p38 MAPK activation is necessary for cancer cell death initiated by a variety of anti-cancer agent (Johnson and Lapadat, 2002; Shim et al., 2007). Consistent with these findings, we observed that activation of p38 MAPK and ERK, but not JNK, are involved in wogonin-induced apoptosis. Further, these effects were abolished by inhibition of ERK and p38 MAPK by pretreatment with inhibitors and these inhibitors attenuated wogo-nin-induced apoptosis. These observations suggest that p38 MAPK and ERK are involved in wogonin-mediated apoptosis. Generally, the ERK signaling cascade is involved in cell proliferation and differentiation (Johnson and Lapadat, 2002). However, ERK signaling pathways are also associated with stress responses and may have proapoptotic roles in cells un-dergoing apoptosis (Lin et al., 2009; Wada and Penninger, 2004; Wang et al., 2000).

Modulation of ROS levels with antioxidants also plays a role in activation of MAPKs (Ueda et al., 2002). In this study, elimination of ROS by NAC reduced ERK and p38 MAPK activation. p38 MAPK is known as a stress-activated MAP kinase (SAPK) and is activated by various stresses such as heat shock, osmotic shock and X-rays, and by proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-α and interleukin-1 (IL-1) (Takeda et al., 2003; Tibbles and Woodgett, 1999). Redox regulation appears to be crucial in SAPK activation under stress. ROS function as inter-mediates in SAPK activation in response to stress agents such as anticancer drugs. Increasing ROS levels promote apoptosis by stimulating pro-apoptotic signaling molecules including MAPKs (Benhar et al., 2002; Davis, 2000; Shen and Liu, 2006; Yoshiike et al., 2008). These finding suggest that ROS generation is involved in wogonin-induced MAPK activation.

In summary, our study shows that wogonin-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells is coupled with generation of ROS and activation of ERK and p38.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates that (1) growth of human breast cancer cells MCF-7 is highly sensitive to wogonin treatment; (2) the decrease of cell proliferation is associated with apoptosis induction; (3) wogonin-induced apoptosis is correlated with activation of both the mitochondrial and death receptor pathways; (4) wogonin treatment increases ROS levels; (5) wogonin treatment is associated with activation of ERK and p38 MAPKs signaling (6) wogonin-induced ERK and p38 activation is involved with the generation of ROS.

These results provide a basic mechanism for the anticancer properties of wogonin and suggest that wogonin is a promising candidate for chemotherapy and chemoprevention in breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the SRC Research Center for Women’s Diseases of Sookmyung Women’s University (2009).

References

- 1.Annunzito L., Amoroso S., Pannaccione A., Cataldi M., Pigna-taro G., D’Alessio A., Sirabella R., Secondo A., Sibaud L., Di Renzo G.F. Apoptosis induced in neuronal cells by oxidative stress: role played by caspases and intracellular calcium ions. Toxicol. Lett. (2003);139:125–133. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(02)00427-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arkin M. Protein-protein interactions and cancer: small mole- cules going in for the kill. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. (2005);9:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benhar M., Engelberg D., Levitzki A. ROS, stress-activated kinases and stress signaling in cancer. EMBO Rep. (2002);3:420–425. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L.G., Hung L.Y., Tsai K.W., Pan Y.S., Tsai Y.D., Li Y.Z., Liu Y.W. Wogonin, a bioactive flavonoid in herbal tea, inhibits inflammatory cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in human lung epithelial cancer cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. (2008);52:1349–1357. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chi Y.S., Lim H., Park H., Kim H.P. Effects of wogo-nin, a plant flavone from Scutellaria radix, on skin inflammation: in vivo regulation of inflammation-associated gene expression. Biochem. Pharmacol. (2003);66:1271–1278. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00463-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung H., Jung Y.M., Shin D.H., Lee J.Y., Oh M.Y., Kim H.J., Jang K.S., Jeon S.J., Son K.H., Kong G. Anti-cancer effects of wogonin in both estrogen receptor-positive and -negative human breast cancer cell lines in vitro and in nude mice xenografts. Int. J. Cancer. (2008);122:816–822. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis R.J. Signal transduction by the JNK Group of MAP kinases. Cell. (2000);103:239–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enomoto R., Suzuki C., Koshiba C., Nishino T., Nakayama M., Hirano H., Yokoi T., Lee E. Wogonin prevents im-munosuppressive action but not anti-inflammatory effect indu-ced by glucocorticoid. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. (2007);1095:412–417. doi: 10.1196/annals.1397.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fresco P., Borges F., Diniz C., Marques M.P. New insights on the anticancer properties of dietary polyphenols. Med. Res. Rev. (2006);26:747–766. doi: 10.1002/med.20060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghobrial I.M., Witzig T.E., Adjei A.A. Targeting apop-tosis pathways in cancer therapy. CA Cancer J. Clin. (2005);55:178–194. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.3.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hengartner M.O. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. (2000);407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang W.H., Lee A.R., Yang C.H. Antioxidative and anti-inflammatory activities of polyhydroxyflavonoids of Scutel-laria baicalensis GEORGI. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. (2006);70:2371–2380. doi: 10.1271/bbb.50698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikemoto S., Sugimura K., Yoshida N., Yasumoto R., Wada S., Yamamoto K., Kishimoto T. Antitumor effects of Scutellariae radix and its components baicalein, baicalin, and wogonin on bladder cancer cell lines. Urology. (2000);55:951–955. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00467-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jemal A., Siegel R., Ward E., Hao Y., Xu J., Thun M.J. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J. Clin. (2009);59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson G.L., Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science. (2002);298:1911–1912. doi: 10.1126/science.1072682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamata H., Hirata H. Redox regulation of cellular signalling. Cell. Signal. (1999);11:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(98)00037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khosravi-Far R., Esposti M.D. Death receptor signals to mitochondria. Cancer Biol. Ther. (2004);3:1051–1057. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.11.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim H., Kim Y.S., Kim S.Y., Suk K. The plant flavo-noid wogonin suppresses death of activated C6 rat glial cells by inhibiting nitric oxide production. Neurosci. Lett. (2001);309:67–71. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar D., Jugdutt B.I. Apoptosis and oxidants in the heart. J. Lab. Clin. Med. (2003);142:288–297. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2143(03)00148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee W.R., Shen S.C., Lin H.Y., Hou W.C., Yang L.L., Chen Y.C. Wogonin and fisetin induce apoptosis in human promyeloleukemic cells, accompanied by a decrease of reactive oxygen species, and activation of caspase 3 and Ca(2+)-dependent endonuclease. Biochem. Pharmacol. (2002);63:225–236. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00876-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee H., Kim Y.O., Kim H., Kim S.Y., Noh H.S., Kang S.S., Cho G.J., Choi W.S., Suk K. Flavonoid wogonin from medicinal herb is neuroprotective by inhibiting inflammatory activation of microglia. FASEB J. (2003);17:1943–1944. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0057fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin K.L., Su J.C., Chien C.M., Tseng C.H., Chen Y.L., Chang L.S., Lin S.R. Naphtho[1,2-b]furan-4,5-dione induces apoptosis and S-phase arrest of MDA-MB-231 cells through JNK and ERK signaling activation. Toxicol. In Vitro. (2009);24:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z.L., Tanaka S., Horigome H., Hirano T., Oka K. Induction of apoptosis in human lung fibroblasts and peripheral lymphocytes in vitro by Shosaiko-to derived phenolic meta-bolites. Biol. Pharm. Bull. (2002);25:37–41. doi: 10.1248/bpb.25.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma S.C., Du J., But P.P., Deng X.L., Zhang Y.W., Ooi V.E., Xu H.X., Lee S.H., Lee S.F. Antiviral Chinese medici-nal herbs against respiratory syncytial virus. J. Ethnopharmacol. (2002);79:205–211. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramos S. Effects of dietary flavonoids on apoptotic path-ways related to cancer chemoprevention. J. Nutr. Biochem. (2007);18:427–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schumacker P.T. Reactive oxygen species in cancer cells: live by the sword, die by the sword. Cancer Cell. (2006);10:175–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen H.-M., Liu Z.-g. JNK signaling pathway is a key modulator in cell death mediated by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Free Rad. Biol. Med. (2006);40:928–939. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shim H.Y., Park J.H., Paik H.D., Nah S.Y., Kim D.S., Han Y.S. Acacetin-induced apoptosis of human breast can-cer MCF-7 cells involves caspase cascade, mitochondria-me-diated death signaling and SAPK/JNK1/2-c-Jun activation. Mol. Cells. (2007);24:95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simon H.U., Haj-Yehia A., Levi-Schaffer F. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. (2000):415–418. doi: 10.1023/a:1009616228304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strasser A., O’Connor L., Dixit V.M. Apoptosis sig-naling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. (2000);69:217–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tai M.C., Tsang S.Y., Chang L.Y., Xue H. Thera-peutic potential of wogonin: a naturally occurring flavonoid. CNS Drug Rev. (2005);11:141–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2005.tb00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeda K., Matsuzawa A., Nishitoh H., Ichijo H. Roles of MAPKKK ASK1 in stress-induced cell death. Cell Struct. Funct. (2003);28:23–29. doi: 10.1247/csf.28.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tibbles L.A., Woodgett J.R. The stress-activated pro-tein kinase pathways. Cell Mol. Life Sci. (1999);55:1230–1254. doi: 10.1007/s000180050369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ueda S., Masutani H., Nakamura H., Tanaka T., Ueno M., Yodoi J. Redox control of cell death. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2002);4:405–414. doi: 10.1089/15230860260196209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wada T., Penninger J.M. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in apoptosis regulation. Oncogene. (2004);23:2838–2849. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X., Martindale J.L., Holbrook N.J. Requirement for ERK activation in cisplatin-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. (2000);275:39435–39443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004583200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang W., Guo Q., You Q., Zhang K., Yang Y., Yu J., Liu W., Zhao L., Gu H., Hu Y., et al. Involvement of bax/bcl-2 in wogonin-induced apoptosis of human hepatoma cell line SMMC-7721. (2006a):797–805. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000217431.64118.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang W., Guo Q.L., You Q.D., Zhang K., Yang Y., Yu J., Liu W., Zhao L., Gu H.Y., Hu Y., et al. The Anticancer Activities of Wogonin in Murine Sarcoma S180 both in vitro and in vivo. Biol. Pharm. Bull. (2006b);29:1132–1137. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshiike Y., Minai R., Matsuo Y., Chen Y.R., Kimura T., Takashima A. Amyloid oligomer conformation in a group of natively folded proteins. PLoS One. (2008);3:e3235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]