Abstract

Campylobacter is a poorly recognized foodborne pathogen, leading the statistics of bacterially caused human diarrhoea in Europe during the last years.

In this review, we present qualitative and quantitative German data obtained in the framework of specific monitoring programs and from routine surveillance. These also comprise recent data on antimicrobial resistances of food isolates. Due to the considerable reduction of in vitro growth capabilities of stressed bacteria, there is a clear discrepancy between the detection limit of Campylobacter by cultivation and its infection potential. Moreover, antimicrobial resistances of Campylobacter isolates established during fattening of livestock are alarming, since they constitute an additional threat to human health.

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) discusses the establishment of a quantitative limit for Campylobacter contamination of broiler carcasses in order to achieve an appropriate level of protection for consumers. Currently, a considerable amount of German broiler carcasses would not comply with this future criterion. We recommend Campylobacter reduction strategies to be focussed on the prevention of fecal contamination during slaughter. Decontamination is only a sparse option, since the reduction efficiency is low and its success depends on the initial contamination concentration.

Keywords: antibiotic resistances, Campylobacter traceability, prevalences in animal and food, quantitative detection, reduction strategies

Impact of Campylobacter as a food-associated pathogen

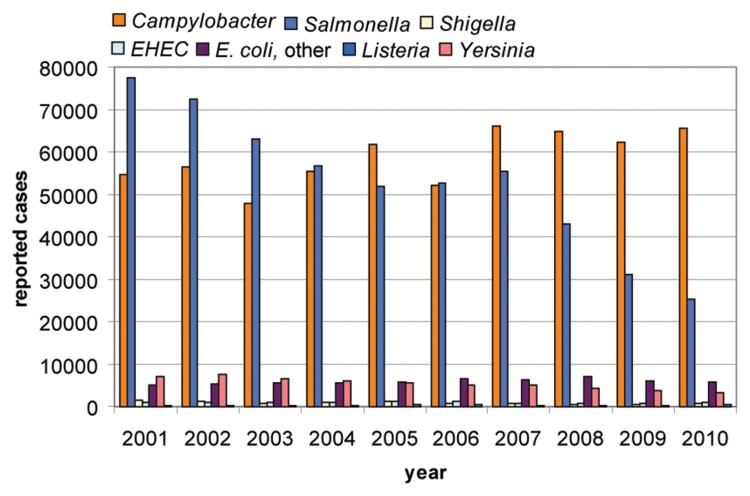

During the last few years, and hardly recognized by the public, Campylobacter is the most prevalent food-poisoning bacterium in Europe. The pathogen causes watery or bloody diarrhoea, which is frequently self-limiting after 4–7 days. Complications of the disease are reactive arthritis and peripheral neuropathies, e.g. the Guillain–Barré syndrome, which is estimated to occur in approximately 1 per 1000 cases (for a recent review on Campylobacter pathogenicity, see Ref. [1]). While a significant decrease in human infections caused by Salmonella could be observed, the frequency of human campylobacteriosis remained high during the last years, leading to more than 65,000 reported cases in 2010 in Germany (Fig. 1, [2]). The total number of reported human campylobacteriosis cases in 2011 was 70,560 in Germany ([2], last update 11.01.2012). This increase is most likely explained by the Shiga-toxin producing O104:H4 E. coli outbreak in Germany in 2011 and the elevated proportion of cases of diarrhoea investigated by medical practitioners. Hence, the true number of campylobacteriosis cases is probably significantly higher and estimated to reach more than four times the reported number [3]. In 2010, among cases with full typing details available, in particular Campylobacter jejuni were involved in human infections in Germany (90.8%), followed by C. coli (8.1%) and C. lari (1%). Only very few human cases were caused by C. upsaliensis (0.07%), C. fetus (0.02%), or others (0.01%).

Fig. 1.

Zoonotic infections in humans in Germany from 2001 until 2010 (data collected by the Robert-Koch Institute [2]). In 2010, the species causing campylobacteriosis were detected as C. jejuni (90.8%), C. coli (8.1%), C. lari (1%), C. upsaliensis (0.07%), C. fetus (0.02%), and others (0.01%).

Detection limitations of Campylobacter and the impact of viable but non-culturable (VBNC) forms

Campylobacter belongs to the ε-proteobacteria, is quite fastidious in vitro, and is limited to growth under microaerobic atmosphere and temperatures of 30–42 °C. The natural multiplication site of this bacterium is the intestine of endotherms, in particular poultry, but also mammals including humans [4]. Once outside the intestine, the bacterium is not capable of growth on food matrices. For several years, standard techniques are available to culture and detect Campylobacter. The ISO standard 10272:2006 details qualitative and quantitative procedures as well as a semiquantitative method for the detection of thermophilic Campylobacter. The high in vitro generation time of Campylobacter compared to competing intestinal flora constitutes the need for selection of Campylobacter by specific antibiotics, to which the bacterium exhibits intrinsic resistance. To improve the power of the detection strategy, two independent selective media are used in combination.

Outside the intestine, the bacterium is particularly confronted with oxidative and cold stress. However, stress situations impair the bacterium’s capacity to subsequently multiply in vitro, thus hindering its proper detection. There are probably all kinds of intermediate states, which might also fail to grow in vitro while maintaining their infectious potential. But frequently observed and most vigorously discussed, Campylobacter transforms into a coccoid form, which definitely fails to grow in vitro [5]. However, such bacterial suspensions are capable of infection in various animal models, from which spiral and culturable Campylobacter were reisolated [6, 7]. Also, the invasion of human epithelial cells was shown using coccoids without capacity to grow on agar plates [8]. Hence, there is a clear discrepancy between the detection limit of Campylobacter by cultivation and its infectious potential, which constitutes a barrier for getting a realistic view about the transmission routes of this pathogen.

Prevalence of Campylobacter in animals and food in Germany

In order to get insight into the distribution of infectious agents transmitted by animals and food, specific monitoring programs for Campylobacter were started in 2009 in Germany based on the European directive 2003/99/EC. By this directive, the European Member States are committed to gather, evaluate, and publish representative data on the prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of zoonotic agents in food, feed, and animals. The Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) coordinates this annual zoonosis monitoring program, in which the competent authorities of the Federal States take samples along the food chain according to a specific sampling plan involving primary production, slaughterhouses, and retail sampling. Hence, the National Reference Laboratory for Campylobacter routinely receives fresh Campylobacter isolates for further analysis in order to get a comprehensive picture about the national situation. Additional isolates come from routine sampling in the framework of surveillance of food producers and retail conducted by the federal authorities (according to regulation 2004/882/EC). The combined efforts intend to provide information about the source of Campylobacter contamination during food production. On this basis, suitable strategies to prevent dissemination of the infectious agents can be envisaged.

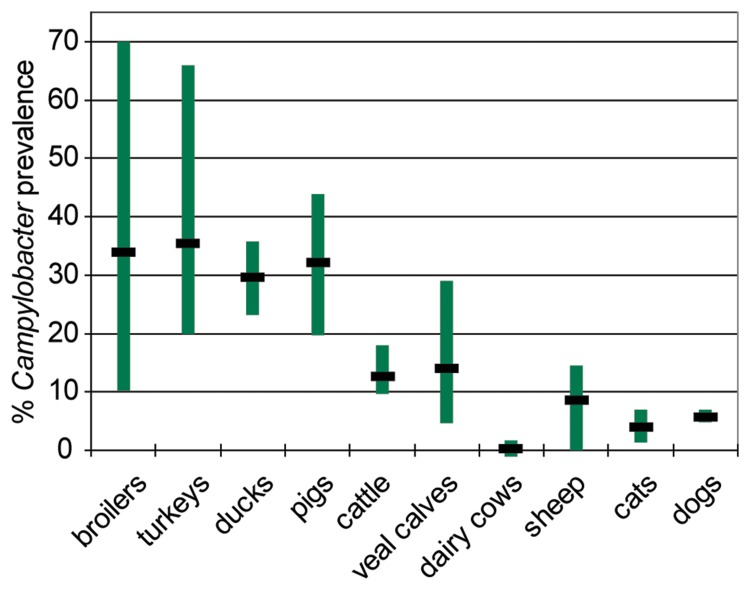

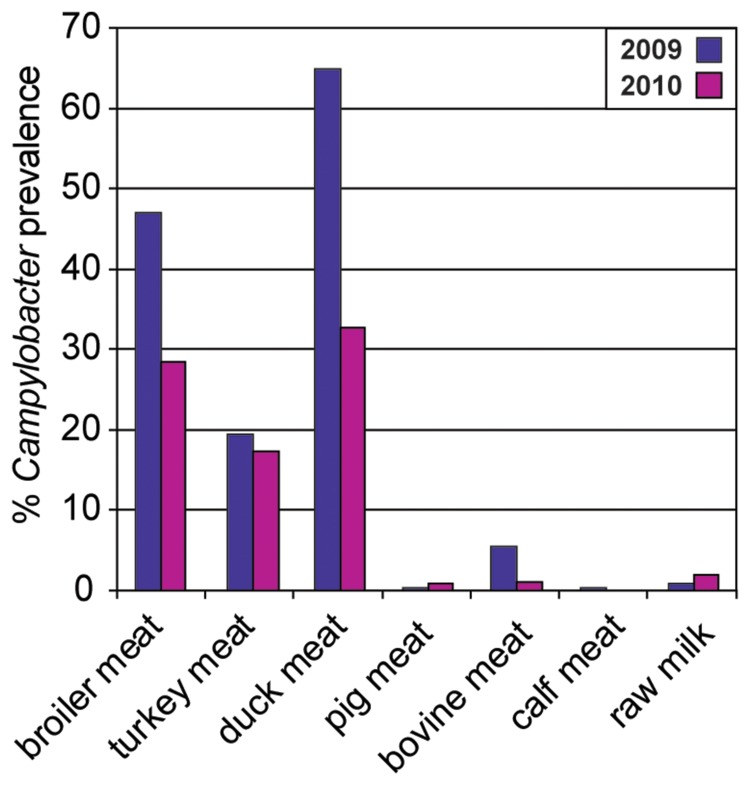

From data obtained in the last 7 years (2004 until 2010) in Germany, it is obvious that Campylobacter is most prevalent in poultry, such as broilers and turkeys, but also ducks, with mean values of around 30–40% and maxima of 36% (ducks) to 66–70% (turkeys and broilers) (Fig. 2). The detection rates varied considerably from year to year, in particular for broilers. This is partly explainable by a variation in the quality of the samples, in terms of Campylobacter culturability (feces from boot socks, feces as fresh droppings, cecum samples, different transport conditions, and time). The lowest annual prevalence rate (10.2%) was found in 2009 using “boot socks”, by which feces were taken from the floor of the chicken house, thereby bearing the risk of collecting Campylobacter after drying. Consistently, it was demonstrated that drying abrogates the culturability (and also viability?) of Campylobacter [9]. As expected from the combined results from poultry flocks, products from this origin are frequently contaminated with Campylobacter, ranging from around 20% positive fresh turkey meat samples, over 30–45% broiler fresh meat, to 30–65% duck meat during the years 2009 and 2010 (Fig. 3). These data have to be considered as the lower limit of Campylobacter prevalence on these products (see also estimation below). In contrast, the mean prevalence of Campylobacter in pigs, cattle, and veal calves ranged from 13% (cattle) and 14% (veal calves) to 32% (pigs) (Fig. 2), whereas the respective meat (Fig. 3) was only rarely contaminated with Campylobacter. The different magnitudes of Campylobacter dissemination in meat is understandable with respect to different slaughtering techniques. The probability for fecal contamination is much higher during slaughter of chicken than of pigs [10, 11]. Since Campylobacter cells do not multiply on food, the initial bacterial contamination is most relevant for the magnitude of the risk of infection for the consumer.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of Campylobacter ssp. in German livestock and pets (2004–2010). Vertical bar: distribution of prevalences detected; horizontal bar: mean. Data are from surveillance and zoonosis monitoring from 2 (ducks, dairy cows), 3 (sheep), 4 (turkeys), 5 (cats, dogs), 6 (cattle), or 7 (broilers, pigs) datasets (years) collected by the BfR.

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of Campylobacter ssp. in German food at retail (2009 and 2010). Data are from zoonosis monitoring, if available, otherwise from surveillance [43–45].

Although poultry meat is considered to be the main cause for infection by Campylobacter (see below), direct contact with pets (dogs, cats, but also farm animals) has to be kept in mind as additional transmission route [12, 13]. The reported prevalence of Campylobacter in dogs and cats is quite stable and ranges at around 5% in Germany (Fig. 2). The prevalence of Campylobacter in dairy cows (0.3%) and raw milk (0.9–1.9%) is reproducibly low, although Campylobacter infections after consumption of nonpasteurized milk have been reported repeatedly [14, 15].

Source attribution of human Campylobacter infections

Campylobacter is considered to be a genetically highly variable organism, capable of horizontal gene transfer and frequent recombination. Furthermore, mixed populations of this organism (co-colonization of genetic variants of one species and/or multiple species) frequently colonize one host organism. The diversity of Campylobacter species and genotypes is certainly underestimated, since one or a few single colonies are routinely diagnosed. The existence of communities of high genetic flexibility probably enhances the bacterium’s fitness for host switchover and adaptation to changing environments, for example, antimicrobial treatments during fattening. This feature of the bacterium aggravates direct genotypic matching of a single food isolate with the respective putative counterpart isolated from humans. As mentioned above, the capability of in vitro growth does not necessarily reflect the capability of host infection. By enrichment and isolation of the bacteria, the most dominant species capable of fastest in vitro growth in the respective selective medium is the one to be detected and identified. Using MLST (multilocus sequence typing), conserved “house-keeping” genes of Campylobacter isolates were sequenced and ordered in terms of similarity. On the basis of MLST data, the authors of a study from England estimated that 57% of all C. jejuni human infections were due to poultry products, 35% originated from cattle, 4% from sheep, less than 1.6% from wild birds, and less than 1% from pigs or from environmental water [16]. According to a study from Scotland, poultry accounted for 58–78% of all C. jejuni and for 40–56% of all C. coli human infections [17]. Turkeys contributed to only less than 1% to the C. coli-caused campylobacteriosis cases. Campylobacter from cattle was considered responsible for 10–12% of C. jejuni and 2–14% C. coli infections, while sheep was assigned for 8–26% C. jejuni and 40% C. coli infections. The contribution of Campylobacter from wild birds, pigs, and the environment as causative agent for human infection was also predicted to be low. In a Finnish study, Campylobacter from poultry were supposed to be equally responsible for human campylobacteriosis as Campylobacter from cattle [18]. The authors explained this phenomenon as due to the low prevalence of Campylobacter in Finnish poultry primary production, which is exceptional in Europe. For Germany, such a study is still missing. The public database for MLST (PubMLST, www.pubmlst.org) comprises currently less than 500 C. jejuni isolates from Germany, but probably (as for all other countries) only a part of the MLST results are submitted. Hence, the publication of a similar analysis with specific source attribution of campylobacteriosis in Germany is expected. However, on the basis of the German prevalence data for Campylobacter in chicken and on carcasses, at least the contribution of poultry products to human Campylobacter infections is anticipated to be as high as estimated for England or Scotland. The EFSA has summarized the available MLST studies from different countries, estimating that 30–50% of the campylobacteriosis cases come from direct consumption and/or handling of chicken meat [3]. The major transmission route might be the consumption of undercooked meat and cross-contamination of meals during the preparation of fresh poultry meat [19]. Moreover, 50–80% of all human Campylobacter infections were attributed to the “chicken reservoir as a whole” [3]. The transmission route of Campylobacter for the latter phenomenon remains to be deciphered. In this context, also the transmission of Campylobacter via contaminated vegetables might play a role [3, 20].

Qualitative versus quantitative detection of Campylobacter

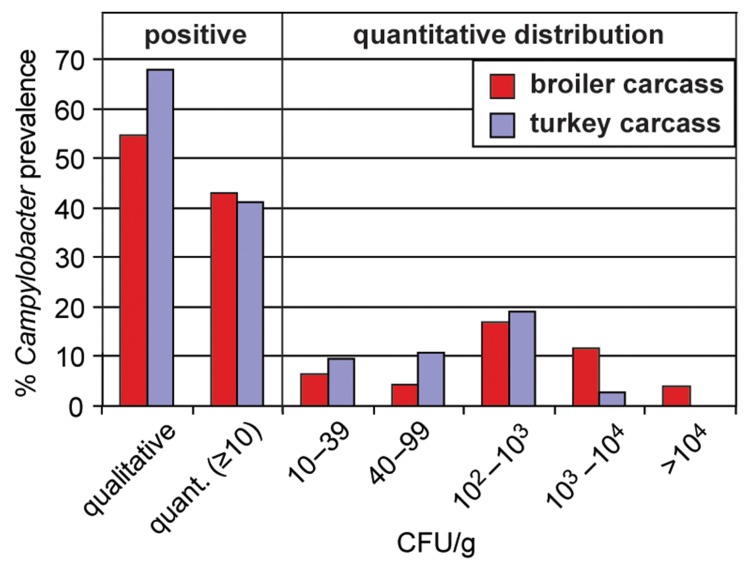

The European baseline study conducted in 2008 was a systematic approach for the detection of Campylobacter on broiler carcasses by analyzing neck skin samples [21]. While using the qualitative method (ISO 10272–1) 55% of the broiler carcasses were Campylobacter positive, the enumeration method (ISO 10272–2) revealed Campylobacter on 43% of the carcasses. According to either method, 62% of the carcasses were Campylobacter-positive [22]. Assuming that this number is the “true number” of positives, 58% of these true positive carcasses (35.9% of all carcasses) were concordantly revealed by both methods. Further, 30% of the true positives (19% of all carcasses) were detected by the qualitative method and 12% (7.2% of all carcasses) were detected only using the quantitative method. It is expected that the qualitative method is superior to quantitative methods concerning sensitivity (the bacterium is first enriched before detection). In contrast, the quantitative method is advantageous in cases of inefficient suppression of competitive flora, outcompeting Campylobacter during enrichment. Direct dilution of the sample and plating on solid agar guarantee the immediate spatial separation of Campylobacter from competing cells.

Interestingly, the proportion of positive carcasses detected by only the quantitative method varied significantly between European Member States [23]. In Belgium, 68% of the total number of positive carcasses was detected only by the quantitative approach, followed by the Netherlands with 32% and Portugal with 16%. The presence of extended β-lactamase (ESBL) producing E. coli can hinder detection via the qualitative ISO method, since those cefoperazone-resistant bacteria grow in Bolton broth used as pre-enrichment medium. Therefore, the data might implicate a different dissemination of ESBL-producing E. coli and/or other resistant background flora in broilers from different European countries. Currently, the use of Preston broth (additionally containing polymyxin B, e. g. for inhibition of ESBL E. coli) for samples with expected high background flora or, alternatively, direct plating of, for example, cecal samples is debated. In the latter samples, Campylobacter is supposed to be present as extremely vital cells in high numbers, justifying the omission of an enrichment step. Still, Bolton broth is accepted to be the most sensitive medium for enrichment of stressed Campylobacter.

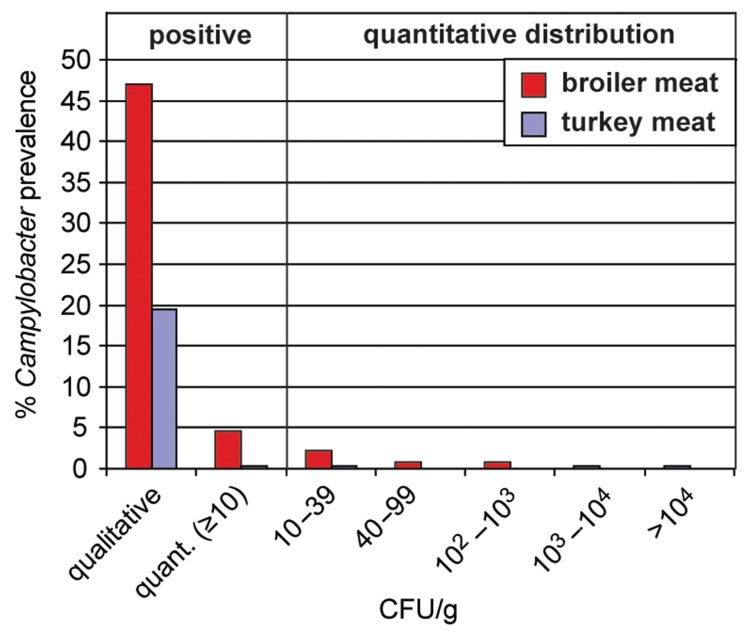

How can the data from broiler and turkey carcasses be interpreted compared to those from meat? Does the reduction of Campylobacter counts detected on meat products indicate safety? From the data obtained from poultry carcasses, it is obvious that broiler carcasses manifest higher Campylobacter loads than turkey carcasses. While 15.5% of broiler carcasses had Campylobacter concentrations higher than 1000 CFU/g, this accounted for only 2.8% of the turkey carcasses (Fig. 4). However, also turkey carcasses were frequently contaminated with Campylobacter, as documented with 68% positively tested samples via qualitative detection. Only one sample was positive according to the quantitative method but failed to be positive after enrichment (0.7% in contrast to 12% of positive broiler carcasses). This might suggest that, in contrast to broilers, background flora did not pose a problem for the detection of Campylobacter in turkeys. It also implicates that the prevalence on broiler carcasses is underestimated by using only the qualitative method.

Fig. 4.

Campylobacter detection on broiler and turkey carcasses in Germany according to ISO 10272–1 (qualitative) and ISO 10272–2 (quantitative). Broiler carcasses from the baseline study 2008 (nqual. = 432, nquant. = 432); turkey carcasses from the zoonosis monitoring 2010 (nqual. = 359, nquant. = 356) [22, 45].

Comparing the Campylobacter contamination of broiler carcasses with fresh meat at retail, the qualitative data do not suggest a reduction of Campylobacter prevalence on broiler meat (Fig. 5). However, while interpreting the quantitative data, a significant reduction of the amount of culturable Campylobacter on meat was observed. First, Campylobacter is predominantly transferred to the meat product via fecal contamination on the surface during slaughter. Part of the meat products were devoid of skin (e.g. breast filet), thereby contributing to a real decrease in Campylobacter concentration. Second, part of the products might have been frozen (the term “fresh meat” also includes frozen meat). Freezing is considered to be a physical decontamination process, leading to a 2 log reduction of Campylobacter concentration after 3 weeks of freezing [3]. Third, stressed and nonculturable cells of Campylobacter do not grow in vitro on selective medium and are not accessible for common detection methods [24]. Under meat storage conditions (4 °C), the number of culturable Campylobacter on chicken skin was reduced by 2 log within the first 2–5 days depending on the strain tested [25]. The quantitative distribution of the Campylobacter concentrations on carcasses peaked at 100–1000 CFU/g (Fig. 4). The results hint at a 3 log Campylobacter reduction when fresh carcasses are compared with fresh meat. We hypothesize that one of the major contributors for reduction of Campylobacter on meat versus carcasses might be an “apparent” reduction due to loss of culturable bacteria, as also observed by Chaisowwong et al. [8]. Further analysis is needed to estimate the “true” reduction caused by death and/or removal of Campylobacter cells. For this purpose, it is necessary to develop appropriate methods for the detection of stressed and viable but nonculturable Campylobacter that do not grow on selective media. In any case, with respect to constant high chicken-derived Campylobacter infection rates, the residual culturable Campylobacter found on poultry meat together with those that are nonculturable and/or dead must be considered a sufficient threat for human infections. As a conclusion, when setting a quantitative value (microbiological criterion) as an efficient strategy for the reduction of Campylobacter, this value is most appropriately monitored at the slaughterhouse. On meat products, the Campylobacter counts do not sufficiently reflect the infection risk for consumers, at least not on the quantitative level.

Fig. 5.

Campylobacter detection on broiler and turkey meat in Germany according to ISO 10272–1 (qualitative) and ISO 10272–2 (quantitative). Broiler meat from the zoonosis monitoring 2009 (nqual. = 413, nquant. = 349); turkey meat from the zoonosis monitoring 2010 (nqual. = 399, nquant. = 564) [44, 45].

Antimicrobial resistance in Campylobacter

In the framework of the zoonosis monitoring, we characterized the antimicrobial resistance profiles of the isolates from food matrices and animal origin in 2009 and 2010 (Fig. 6 and 7). Over 1000 German Campylobacter isolates were subjected to antimicrobial resistance profiling. In order to cover all relevant food chains with a representative number of samples, maintaining practicability for the Federal States, the monitoring program focuses every year on a subset of pathogen–matrix combinations. In 2009, Campylobacter isolates were analyzed from chicken (feces from laying hens and broilers) and broiler meat as well as from veal calves (colon) and from raw milk at farm. In 2010, the same was done for isolates from turkeys at slaughter (cecum, carcass) and turkey meat at retail, and again from raw milk. Seven antimicrobials representing five different classes were tested using the microdilution method and a European-wide standardized microplate format (EUCAMP). The results were interpreted using epidemiological cut-off values according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST, Table 1).

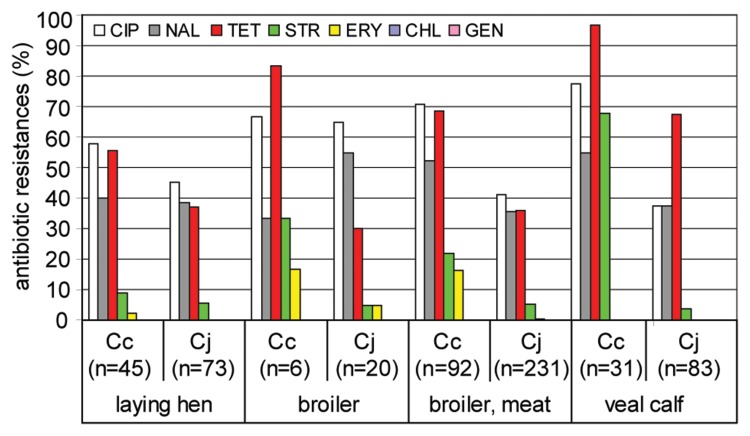

Fig. 6.

Antimicrobial resistances of Campylobacter isolates from laying hen, broiler, broiler meat, and veal calf. CIP, ciprofloxacin; NAL, nalidixic acid; TET, tetracycline; STR, streptomycin; ERY, erythromycin; CHL, chloramphenicol; GEN, gentamicin; Cj, C. jejuni; Cc, C. coli; n, number of tested isolates. Isolates stem from the zoonosis monitoring program 2009; isolates from broiler meat stem from both monitoring and surveillance.

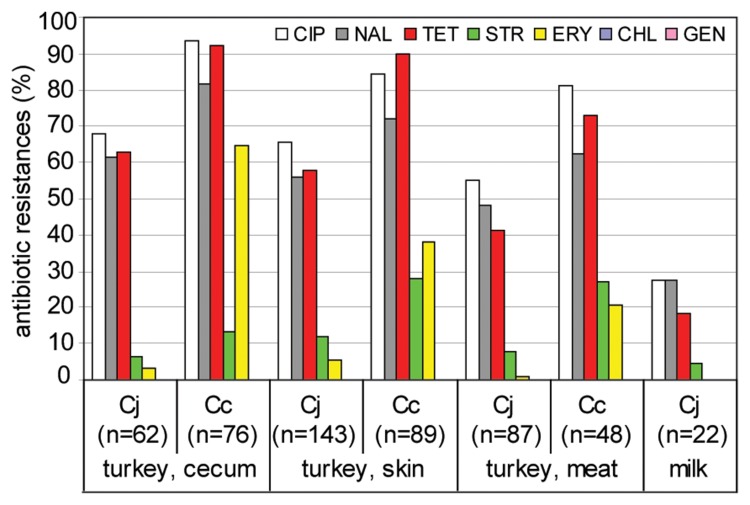

Fig. 7.

Antimicrobial resistances of Campylobacter isolates from turkey cecum, skin, and meat, and from milk. CIP, ciprofloxacin; NAL, nalidixic acid; TET, tetracycline; STR, streptomycin; ERY, erythromycin; CHL, chloramphenicol; GEN, gentamicin; Cj, C. jejuni; Cc, C. coli. Isolates stem from the zoonosis monitoring program 2010. Isolates from turkey meat and raw milk originate from both monitoring and surveillance. Due to the low number isolates from raw milk, isolates obtained in 2009 and 2010 were pooled.

Table 1.

Test range of antibiotic concentrations and interpretation criteria for C. jejuni and C. coli

| Class | Antimicrobial | Cut-off # (µg ml−1) |

Range of test

concentrations |

Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum (µg ml−1) |

Maximum (µg ml−1) |

||||

| Aminoglycoside | GEN | 1*/2** | 0.125 | 16 | 2007/516/EG |

| STR | 2*/4** | 1 | 16 | 2007/516/EG | |

| (Fluoro-)quinolone | NAL | 16*/32** | 2 | 64 | EUCAST |

| CIP | 1 | 0.06 | 4 | 2007/516/EG | |

| Tetracycline | TET | 2 | 0.25 | 16 | 2007/516/EG |

| Macrolide | ERY | 4*/16** | 0.5 | 32 | 2007/516/EG |

| Phenicol | CHL | 16 | 2 | 32 | EUCAST |

| *C. jejuni, **C. coli cut-off values were defined according to the European decision 2007/516/EG or according to EUCAST (www.eucast.org). CIP, ciprofloxacin; NAL, nalidixic acid; TET, tetracycline; STR, streptomycin; ERY, erythromycin; CHL, chloramphenicol; GEN, gentamicin; #, values higher than the cut-off value indicate resistance. | |||||

Our data show that Campylobacter isolated from food and animals exhibit high resistance, in particular to fluoro-quinolones and tetracycline (Fig. 6 and 7). The proportion of resistant isolates depended on the origin and Campylobacter species. In general and previously observed by others [26], C. coli were significantly more resistant than C. jejuni. Resistance to ciprofloxacin was frequently observed in around 40% of the C. jejuni isolates from veal calves and broiler meat as well as to over 90% for C. coli isolates from turkey cecum samples. In veal calves, nearly all C. coli (97%) and 68% of the C. jejuni isolates were tetracycline-resistant. In isolates from poultry origin, tetracycline resistance of C. coli ranged between 56% (laying hens) and over 90% (turkey, cecum and veal calves) and that of C. jejuni between 30% (broiler) and 68% (veal calves).

But also resistances to streptomycin and erythromycin were considerable (Fig. 6 and 7). The species-specific degree of resistance was especially obvious for the prevalence of resistance against erythromycin and streptomycin. While 65% C. coli isolates were erythromycin-resistant when isolated from turkey cecum, this accounted for 40% C. coli from turkey skin and around 20% from turkey meat. In contrast, the proportion of erythromycin-resistant C. jejuni from the same origins ranged between 1.1% and 5.6%. An analogous situation was revealed for streptomycin resistance, for which species differences were most pronounced in isolates from veal calves. Here, 68% of the C. coli exhibited streptomycin resistance, while this was the case for only 4% of the respective C. jejuni isolates. The reason for this phenomenon remains to be elucidated.

The fact that isolates from milk had rather low overall resistance rates suggested that antibiotic administration to dairy cows might have been lower than to the other tested farm animals. However, due to the low prevalence of Campylobacter in raw milk, only few isolates were tested (n = 6 in 2009, n = 16 in 2010).

Also, the number of Campylobacter isolates for antimicrobial resistance analysis from broiler flocks was rather low (n = 26), since boot socks appear to be an inadequate collection device for culturable Campylobacter from feces (see above). Further representative data on German broilers will be available soon from the monitoring conducted in 2011 on the basis of cecal samples. But nevertheless, the statistics of antimicrobial resistance on Campylobacter from broiler meat collected in 2009 was deduced from a sufficiently large number of isolates (n = 323). Since broiler meat is supposed to constitute the major source of infection for human campylobacteriosis, Campylobacter isolates from this origin should principally match the prevalence of antimicrobial resistances of human isolates. When comparing data from human isolates collected by the Robert-Koch institute (data from 2005–2007, [27]), a low amount of both C. jejuni and C. coli human isolates (5–8%) showed resistance to chloramphenicol and gentamicin, which was not the case in isolates from food and animals. However, the overall antimicrobial resistances of C. jejuni isolates from broiler correlated well with those from isolates of human origin (R2 = 0.82), while those of C. coli did not (R2 = 0.47). This may suggest that a considerable proportion of C. coli originated from a different source than broiler. Alternatively, or in addition, it might be indicative of a higher adaptive potential of C. coli, more rapidly losing and/or gaining new antimicrobial resistances when facing changing environments (human host).

In conclusion, the prevalence of antimicrobial resistances in Campylobacter from food and food-producing animals is alarming, because resistant bacteria can frequently be transmitted to the human host. Although most of the Campylobacter infections do not require antimicrobial treatment, severe cases, especially in immunocompromised patients, demand effective antibiotics for treatment of campylobacteriosis. Thus, the high antimicrobial resistance rates found in Campylobacter constitute an additional risk, to which the consumer is exposed to upon transmission of this pathogen via food. These data again demonstrate that there is an urgent need to minimize antimicrobial treatment in primary production.

Reduction strategies

Since broiler chickens constitute the main source for Campylobacter infections, reduction strategies focus on production of broiler meat. According to a mathematical model, the EFSA estimates that a reduction of human campylobacteriosis by 50% or 90% can be achieved if a microbiological criterion of 1000 or 500 CFU/g carcass skin, respectively, is established [3]. Currently, 15.5% of the broiler carcasses and 2.8% of the turkey carcasses in Germany would not comply with the upper limit of 1000 CFU/g (Fig. 4). Hence, a quantitative reduction of Campylobacter on chicken carcasses is crucial. In principle, the prevalence of foodborne zoonotic pathogens can be reduced at different levels of the food chain, such as primary production (prevention of pathogen entry into the food processing chain), slaughtering process (prevention of fecal contamination), and post slaughtering (decontamination).

Unlike Salmonella, Campylobacter is not vertically transmitted from breeder flock to progeny but its dissemination is merely horizontal [28]. Therefore, hygienic measures in primary production are essential to avoid spread of the bacterium and are considered to be key strategies for reduction of Campylobacter loads on food [3]. The probability of Campylobacter colonization increases with the age of the chicken [3]. Recent evidence was provided that the latter can be explained by the combined effect of colonization resistance of young chickens mediated by maternal antibodies and the probability of Campylobacter exposure [29]. Intriguingly and currently inexplicable, newly hatched chicken were highly susceptible towards Campylobacter colonization, although the level of maternal antibodies was the highest. However, resistance was established within 3 days and lasted for over 3 weeks. More work is needed to understand the interplay between Campylobacter, the host immune system, and microbiota, which are key players in defining the colonization capacity of the bacterium [30].

Campylobacter-specific bacteriophages could potentially be exploited to decrease bacterial concentration in poultry prior to slaughter. Using different bacteriophages, a transient 1.5–5 log reduction in cecal Campylobacter concentrations, peaking approximately 2 days post administration, was observed in chickens (reviewed in Ref. [31]). Hence, current research aims to understand the molecular and phenotypic variety of different types of natural bacteriophages [32–35] in order to rationally design an appropriate cocktail for efficient reduction of Campylobacter in practice.

Campylobacter is accepted to be primarily a superficial contamination, which occurs during slaughtering [36]. The bacterium was occasionally also found inside the muscle of poultry meat collected at retail, however, quantitatively in very low numbers [37], and it is yet unclear if these Campylobacter recently originated from skin (via lesions) or had systemically been transmitted via blood. Freezing for 3 weeks is considered to be a physical decontamination strategy, which results in a decrease of Campylobacter counts by 2 logs. In contrast, there is an increasing demand for fresh, nonfrozen meat on the market. It is established that the bacterium tightly adheres to skin and meat surfaces. Since Campylobacter was found in deep crypts of the chicken skin [38], it is expected that, once spread over the surface of the chicken, its removal is rather complicated. Indeed, chemical decontamination resulted only in a reduction of Campylobacter concentration by around 1 log (on average) depending on the chemical and concentration used [3, 39].

Hence, the prevention of fecal contamination during slaughter appears to be the most efficient strategy for limiting the spread of the pathogen to food. Short-term feed withdrawal before slaughter for reduction of the amount of intestinal content is one of the means already implemented in practice [40]. When does fecal contamination take place most predominantly? Contamination of skin and feathers during transport due to leakage of feces is to be considered. However, quantitatively it is not comparable with the amount of feces distributed during slaughter. A study clearly showed the effect of contamination by fecal exit during defeathering. The cloacae of one group of chicken were closed by plugging and suturation after electrocution and scalding [41]. Post defeathering, Campylobacter counts on the carcass were determined quantitatively. While the control group was 100% Campylobacter-positive with an average of 4.5 log Campylobacter per carcass, 89% of the cloacae-sewed chicken were negative, with a residual 11% positive carcasses bearing 2.5 log Campylobacter on average per carcass. These results demonstrate that the main contamination stems from feces escape from the respective chicken during slaughter. Recently, variations in the slaughter process were tested for efficiency of reduction in fecal contamination during picking. The effect of hanging broiler carcasses with the vent down to allow escaped feces to fall on the ground rather than disseminate across the carcass was characterized by using the same standard shackle line [42]. With this approach, the plucking fingers probably exerted vigorous movement of the broiler carcass in all spatial dimensions during defeathering, which is ideal in the propagation of escaped feces across the carcass surface instead of ensuring its loss by gravity. Consistently, this method was shown to be ineffective in prevention of Campylobacter spread [42]. In future trials, it remains to be shown whether the (in principle) promising upside-down hang can be combined with a cloacal plugging device inserted from below the shackle line or even with concomitant evisceration from below in order to efficiently prevent fecal spread. Moreover, alternative spray-/splash-scalding processes have to be developed, lacking a common scalding tank for all carcasses, which leads to cross-contamination. In general, Campylobacter spread from feces to the carcass has to be prevented and should be in the focus of reduction strategies. This would not only lead to reduction of Campylobacter but also of any other potentially harmful intestinal microbes.

Conclusions

There is a clear gap in Campylobacter traceability and knowledge on its potential to colonize various hosts. More research is needed to understand its success as a foodborne pathogen, which might be related to its enormous capability to develop genetic variants. Furthermore, the frequent antimicrobial resistance established during fattening has to be considered a significant threat to human health. The most realistic prevalence data on Campylobacter are obtained from fresh samples (e.g. at the slaughterhouse), where detection by cultivation methods is appropriate. We recommend reduction strategies to be focused on the prevention of fecal contamination during slaughter. Decontamination presents only a limited option, since the reduction efficiency is low and its success depends on the initial contamination concentration.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the competent authorities of the Federal States for isolating Campylobacter spp., which is the basis for such a comprehensive monitoring dataset from Germany. They are also grateful to Dr. Erhard Tietze and Dr. Antje Flieger from the Robert-Koch Institute for discussions of antimicrobial resistance data from humans and food.

Contributor Information

K. Stingl, Department of Biological Safety, Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, Diedersdorfer Weg 1, 12277 Berlin, Germany.

M.-T. Knüver, Department of Biological Safety, Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, Diedersdorfer Weg 1, 12277 Berlin, Germany

P. Vogt, Department of Biological Safety, Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, Diedersdorfer Weg 1, 12277 Berlin, Germany

C. Buhler, Department of Biological Safety, Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, Diedersdorfer Weg 1, 12277 Berlin, Germany

N.-J. Krüger, Department of Biological Safety, Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, Diedersdorfer Weg 1, 12277 Berlin, Germany

K. Alt, Department of Biological Safety, Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, Diedersdorfer Weg 1, 12277 Berlin, Germany

B.-A. Tenhagen, Department of Biological Safety, Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, Diedersdorfer Weg 1, 12277 Berlin, Germany

M. Hartung, Department of Biological Safety, Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, Diedersdorfer Weg 1, 12277 Berlin, Germany

A. Schroeter, Department of Biological Safety, Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, Diedersdorfer Weg 1, 12277 Berlin, Germany

L. Ellerbroek, Department of Biological Safety, Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, Diedersdorfer Weg 1, 12277 Berlin, Germany

B. Appel, Department of Biological Safety, Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, Diedersdorfer Weg 1, 12277 Berlin, Germany

A. Käsbohrer, Department of Biological Safety, Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, Diedersdorfer Weg 1, 12277 Berlin, Germany

References

- 1.Dasti JI, Tareen AM, Lugert R, Zautner AE, Gross U. Campylobacter jejuni: a brief overview on pathogenicity-associated factors and disease-mediating mechanisms. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010 Apr;300(4):205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robert-Koch Institute, Survstat. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.EFSA Scientific Opinion on Campylobacter in broiler meat production: control options and performance objectives and/or targets at different stages of the food chain. EFSA J. 2011;9:2105. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vandamme P. Taxonomy of the family Campylobacteraceae. In: Namchamkin I, Blaser MJ, editors. Campylobacter. Washington DC: ASM; 2000. pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rollins DM, Colwell RR. Viable but nonculturable stage of Campylobacter jejuni and its role in survival in the natural aquatic environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986 Sep;52(3):531–538. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.3.531-538.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baffone W, Casaroli A, Citterio B, Pierfelici L, Campana R, Vittoria E, Guaglianone E, Donelli G. Campylobacter jejuni loss of culturability in aqueous microcosms and ability to resuscitate in a mouse model. Int J Food Microbiol. 2006 Mar 1;107(1):83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stern NJ, Jones DM, Wesley IV, Rollins DM. Colonization of chicks by non-culturable Campylobacter spp. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994;18:333–336. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaisowwong W, Kusumoto A, Hashimoto M, Harada T, Maklon K, Kawamoto K. Physiological characterization of Campylobacter jejuni under cold stresses conditions: its potential for public threat. J Vet Med Sci. 2012 Jan;74(1):43–50. doi: 10.1292/jvms.11-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humphrey T, Mason M, Martin K. The isolation of Campylobacter jejuni from contaminated surfaces and its survival in diluents. Int J Food Microbiol. 1995 Aug;26(3):295–303. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)00135-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearce RA, Wallace FM, Call JE, Dudley RL, Oser A, Yoder L, Sheridan JJ, Luchansky JB. Prevalence of Campylobacter within a swine slaughter and processing facility. J Food Prot. 2003 Sep;66(9):1550–1556. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-66.9.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wehebrink T, Kemper N, grosse Beilage E, Krieter J. Prevalence of Campylobacter spp. and Yersinia spp. in the pig production. Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 2008 Jan-Feb;121(1-2):27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damborg P, Olsen KE, Møller Nielsen E, Guardabassi L. Occurrence of Campylobacter jejuni in pets living with human patients infected with C. jejuni. J Clin Microbiol. 2004 Mar;42(3):1363–1364. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1363-1364.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tenkate TD, Stafford RJ. Risk factors for campylobacter infection in infants and young children: a matched case-control study. Epidemiol Infect. 2001 Dec;127(3):399–404. doi: 10.1017/s0950268801006306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heuvelink AE, van Heerwaarden C, Zwartkruis-Nahuis A, Tilburg JJ, Bos MH, Heilmann FG, Hofhuis A, Hoekstra T, de Boer E. Two outbreaks of campylobacteriosis associated with the consumption of raw cows' milk. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009 Aug 31;134(1-2):70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newkirk R, Hedberg C, Bender J. Establishing a milkborne disease outbreak profile: potential food defense implications. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011 Mar;8(3):433–437. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson DJ, Gabriel E, Leatherbarrow AJ, Cheesbrough J, Gee S, Bolton E, Fox A, Fearnhead P, Hart CA, Diggle PJ. Tracing the source of campylobacteriosis. PLoS Genet. 2008 Sep 26;4(9):e1000203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheppard SK, Dallas JF, Strachan NJ, MacRae M, McCarthy ND, Wilson DJ, Gormley FJ, Falush D, Ogden ID, Maiden MC, Forbes KJ. Campylobacter genotyping to determine the source of human infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Apr 15;48(8):1072–1078. doi: 10.1086/597402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Haan CP, Kivistö RI, Hakkinen M, Corander J, Hänninen ML. Multilocus sequence types of Finnish bovine Campylobacter jejuni isolates and their attribution to human infections. BMC Microbiol. 2010 Jul 26;10:200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luber P, Brynestad S, Topsch D, Scherer K, Bartelt E. Quantification of campylobacter species cross-contamination during handling of contaminated fresh chicken parts in kitchens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006 Jan;72(1):66–70. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.1.66-70.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verhoeff-Bakkenes L, Jansen HA, in 't Veld PH, Beumer RR, Zwietering MH, van Leusden FM. Consumption of raw vegetables and fruits: a risk factor for Campylobacter infections. Int J Food Microbiol. 2011 Jan 5;144(3):406–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.EFSA Analysis of the baseline survey on the prevalence of Campylobacter in broiler batches and of Campylobacter and Salmonella on broiler carcasses in the EU, 2008; Part A: Campylobacter and Salmonella prevalence estimates. EFSA J. 2010;8:1503. [Google Scholar]

- 22.BfR, Grundlagenstudie zum Vorkommen von Campylobacter spp. und Salmonella spp. in Schlachtkörpern von Masthähnchen vorgelegt [Baseline study on the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. and Salmonella spp. on broiler carcasses]. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.EFSA Analysis of the baseline survey on the prevalence of Campylobacter in broiler batches and of Campylobacter and Salmonella on broiler carcasses, in the EU, 2008; Part B: Analysis of factors associated with Campylobacter colonisation of broiler batches and with Campylobacter contamination of broiler carcasses; and investigation of the culture method diagnostic characteristics used to analyse broiler carcass samples. EFSA J. 2010;8:1522. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas C, Hill D, Mabey M. Culturability, injury and morphological dynamics of thermophilic Campylobacter spp. within a laboratory-based aquatic model system. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;92(3):433–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Shibiny A, Connerton P, Connerton I. Survival at refrigeration and freezing temperatures of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni on chicken skin applied as axenic and mixed inoculums. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009 May 31;131(2-3):197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luangtongkum T, Jeon B, Han J, Plummer P, Logue CM, Zhang Q. Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter: emergence, transmission and persistence. Future Microbiol. 2009 Mar;4(2):189–200. doi: 10.2217/17460913.4.2.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.BVL, RKI, PEG, GERMAP 2008 – Antibiotika-Resistenz und -Verbrauch [GERMAP 2008 – antimicrobial resistance and consumption]. Freiburg: Bundesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit, Paul-Ehrlich-Gesellschaft für Chemotherapie, and Infektiologie; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Callicott KA, Friethriksdóttir V, Reiersen J, Lowman R, Bisaillon JR, Gunnarsson E, Berndtson E, Hiett KL, Needleman DS, Stern NJ. Lack of evidence for vertical transmission of Campylobacter spp. in chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006 Sep;72(9):5794–5798. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02991-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cawthraw SA, Newell DG. Investigation of the presence and protective effects of maternal antibodies against Campylobacter jejuni in chickens. Avian Dis. 2010 Mar;54(1):86–93. doi: 10.1637/9004-072709-Reg.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bereswill S, Fischer A, Plickert R, Haag LM, Otto B, Kühl AA, Dasti JI, Zautner AE, Muñoz M, Loddenkemper C, Gross U, Göbel UB, Heimesaat MM. Novel murine infection models provide deep insights into the "ménage à trois" of Campylobacter jejuni, microbiota and host innate immunity. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Connerton PL, Timms AR, Connerton IF. Campylobacter bacteriophages and bacteriophage therapy. J Appl Microbiol. 2011 Aug;111(2):255–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammerl JA, Jäckel C, Reetz J, Beck S, Alter T, Lurz R, Barretto C, Brüssow H, Hertwig S. Campylobacter jejuni group III phage CP81 contains many T4-like genes without belonging to the T4-type phage group: implications for the evolution of T4 phages. J Virol. 2011 Sep;85(17):8597–8605. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00395-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansen VM, Rosenquist H, Baggesen DL, Brown S, Christensen BB. Characterization of Campylobacter phages including analysis of host range by selected Campylobacter Penner serotypes. BMC Microbiol. 2007 Oct 18;7:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kropinski AM, Arutyunov D, Foss M, Cunningham A, Ding W, Singh A, Pavlov AR, Henry M, Evoy S, Kelly J, Szymanski CM. Genome and proteome of Campylobacter jejuni bacteriophage NCTC 12673. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011 Dec;77(23):8265–8271. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05562-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Timms AR, Cambray-Young J, Scott AE, Petty NK, Connerton PL, Clarke L, Seeger K, Quail M, Cummings N, Maskell DJ, Thomson NR, Connerton IF. Evidence for a lineage of virulent bacteriophages that target Campylobacter. BMC Genomics. 2010 Mar 30;11:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenquist H, Sommer HM, Nielsen NL, Christensen BB. The effect of slaughter operations on the contamination of chicken carcasses with thermotolerant Campylobacter. Int J Food Microbiol. 2006 Apr 25;108(2):226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scherer K, Bartelt E, Sommerfeld C, Hildebrandt G. Quantification of Campylobacter on the surface and in the muscle of chicken legs at retail. J Food Prot. 2006 Apr;69(4):757–761. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-69.4.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chantarapanont W, Berrang M, Frank JF. Direct microscopic observation and viability determination of Campylobacter jejuni on chicken skin. J Food Prot. 2003 Dec;66(12):2222–2230. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-66.12.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chantarapanont W, Berrang ME, Frank JF. Direct microscopic observation of viability of Campylobacter jejuni on chicken skin treated with selected chemical sanitizing agents. J Food Prot. 2004 Jun;67(6):1146–1152. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-67.6.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warriss PD, Wilkins LJ, Brown SN, Phillips AJ, Allen V. Defaecation and weight of the gastrointestinal tract contents after feed and water withdrawal in broilers. Br Poult Sci. 2004 Feb;45(1):61–66. doi: 10.1080/0007166041668879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berrang ME, Buhr RJ, Cason JA, Dickens JA. Broiler carcass contamination with Campylobacter from feces during defeathering. J Food Prot. 2001 Dec;64(12):2063–2066. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-64.12.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berrang ME, Buhr RJ, Cason JA, Dickens JA. Variations on standard broiler processing in an effort to reduce Campylobacter numbers on postpick carcasses. J Appl Poult Res. 2011;20:197–202. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hartung M, Käsbohrer A. Campylobacter. In: Hartung M, Käsbohrer A, editors. Erreger von Zoonosen in Deutschland im Jahr 2009 [Zoonotic agents in Germany in the year 2009] Berlin: BfR Wissenschaft; 2011. Jan, pp. 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Käsbohrer A, Tenhagen B-A, Alt K, Stingl K. Erreger von Zoonosen in Deutschland im Jahr 2009 [Zoonotic agents in Germany in the year 2009] Berlin: BfR Wissenschaft; 2011. Jan, Campylobacter-Monitoringprogramme [Campylobacter monitoring programs] pp. 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Käsbohrer A, Tenhagen B-A, Alt K, Stingl K. Campylobacter-Monitoringprogramme [Campylobacter monitoring programs] In: Hartung M, Käsbohrer A, editors. Erreger von Zoonosen in Deutschland im Jahr 2010 [Zoonotic agents in Germany in the year 2010] Berlin: BfR Wissenschaft; 2010. in press. [Google Scholar]